Abstract

Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) continues to afflict approximately 7% of preterm infants born weighing less than 1500 grams, though recent investigations have provided novel insights into the pathogenesis of this complex disease1. The disease has been a major cause of morbidity and mortality in neonatal intensive care units worldwide for many years, and our current understanding reflects exceptional observations made decades ago. In this review, we will describe NEC from a historical context and summarize seminal findings that underscore the importance of enteral feeding, the gut microbiota, and intestinal inflammation in this complex pathophysiology.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Although not described as classic NEC, a report from almost 200 years ago by Charles Billard described a case from the Hopital Des Infants Trouves in Paris, France in which ‘a foundling newborn developed a swollen abdomen with greenish then bloody diarrhea, developing a tense abdomen, cold extremities, bradycardia, and subsequent death.’ The autopsy of this patient described an intensely red and swollen terminal ileum, with friable mucosa and the surface covered with blood. In fact, the mucosa was so soft that it ‘turned to mash when scraped with the fingernail’. This description is consistent with clinical findings that are sometimes observed in our NEC patients now, and may be the first published account of NEC. (reference)

In 1944 Heinrich Willi reported on 62 cases of ‘malignant enteritis’ in newborns. These cases were of interest in that 2/3 of them had birthweights under 2500 grams, they seemed to be associated with overcrowding in the nursery, and they typically occurred in clusters. These observations may be the first describing what subsequently was reported as a ‘NEC epidemic’, though these events are distinctly uncommon in the current era. (reference)

There were 85 cases described in 1952 by Schmidt and Kaiser in two reports where newborn patients had abdominal symptoms, bloody stools, and pathological evidence of ulcerated and necrotic bowel that they termed ‘enterocolitis ulcerosa necroticans’, or the fore-runner of necrotizing enterocolitis2. These publications are often credited as the first descriptions of NEC, and framed the disease for many subsequent investigators to analyze and ascertain.

Around the same time, in 1951, a radiologist in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Arthur Steinen observed pneumatosis intestinalis in the radiograph from a newborn patient with bloody stools, and described ‘from the mesenteric root gas can dissect, extend to the mesenteric insertion of the intestine and from here either dissect along the subserosal layers or, following the blood vessels…enter the submucosa’. This finding has become the radiologic hallmark of NEC, and scientists have speculated on the contribution of this gas in the bowel wall to include hydrogen gas as a byproduct from bacterial fermentation on carbohydrate substrate. (reference) Though controversial, this may explain why NEC may occur in very preterm patients without evidence of pneumatosis intestinalis, particularly before enteral feedings have been well established.

In the 1950’s and 1960’s, as more and more preterm infants were able to survive due to advances in neonatal care for very low birth weight infants, there was a significant and consistent rise in cases of necrotizing enterocolitis. During that time, there were several colleagues at the Babies Hospital of Columbia University in New York that conducted extensive analyses from newborns with NEC and animal experiments in the laboratory setting. These investigators concluded that hypoxia was an important initiator of the development of intestinal injury in this population, but that enteral feedings, intestinal microbial flora, and inflammation all contributed to the final common pathway of disease. These studies demonstrated that Gram negative bacteria contributed significantly to the outcome of NEC, and that prematurity was an important risk factor, presumably due to impaired host defense. While the impact of mesenteric ischemia and hypoxia on NEC pathogenesis remains controversial, the remaining risk factors of enteral feeding, dysbiosis, and intestinal inflammation have gained additional support following innovative and reproducible observations over the course of time.

ENTERAL FEEDINGS IN NEC PATHOGENESIS

In the early 1970’s, Dr. Barlow and colleagues in New York developed a newborn rat model of NEC that included formula feeding, intermittent asphyxia, and bacterial colonization3. Initial studies demonstrated that rat mother’s milk feedings completely protected against NEC compared to newborn pups who received formula feedings, and it was hypothesized that breast milk feedings provided mucosal immunity that promoted colonization with commensal microbes thus allowing for normal mucosal epithelial cell repair and regeneration. Formula feedings were suggested to promote gut dysbiosis with overgrowth of enteric bacteria, mucosal translocation, and the development of NEC. Subsequent studies showed that while fresh milk was protective, frozen milk was ineffective, and it was the leukocyte fraction that was important in preventing the development of disease4.

As cases of NEC were increasing, in the mid 1970’s Drs. Brown and Sweet at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York hypothesized that aggressive feeding approaches contributed to the development of NEC in premature infants, and embarked on a strict feeding regimen to reduce the risk in their population5. They devised a careful protocol in which feeding volumes and formula strength were initially begun at low levels, and slowly advanced over a two week course to attain ‘full’ enteral volumes and calories. Based on this approach, they reported that they almost completely prevented NEC in their NICU population, and that a prospective, randomized and controlled trial was unethical to study their innovative protocol. Based on this supposition, they reported that only 1/932 low birth weight (less than 2500 grams) infant developed NEC with the strict feeding regimen compared to 14/1745 (0.8%, p = 0.026) of historic controls. This was a provocative report, and likely influenced the feeding strategies for many providers in NICU settings around the country.

Throughout the 1980’s and 90’s, several studies showed that early hypocaloric or trophic feedings (given at approximately 15–20 ml/kg/day) as compared to a prolonged period of nothing by mouth (NPO) benefitted preterm infants with less hyperbilirubinemia, less osteopenia of prematurity, and more rapid attainment of full enteral feedings without the risk of increased incidence of NEC6,7. Therefore, most neonatologists began early trophic feedings, and the pendulum swung towards earlier and faster advancement of the feeding protocol. In 2003, Dr. Berseth and colleagues reported a prospective randomized trial that showed delayed advancement of hypocaloric feedings by 10 days reduced the risk of NEC significantly compared to patients that began earlier advancements (NEC incidence 10% for advancing volume group v. 1.4% for delayed advancement, p =0.03)8. This result was provocative and some NICU’s adopted this practice of delayed feeding advancement, though similar to Berseth’s own data, these patients were at increased risk of central line infections associated with prolonged need for intravenous cannulation and hyperalimentation. It remained unclear whether the size of feeding volume increases on a day to day basis contributed to NEC, and some investigators conducted studies to evaluate this supposition. Based on a reasonably low number of patients randomized, a meta-analysis was recently published in the Cochrane Review that suggested the size of feeding volume increases did not influence the development of NEC9. It should be noted that the power of this conclusion was small, though the takeaway was that daily advances between 15 ml/feed up to 35 ml/feed did not differentially contribute to NEC pathogenesis. Overall, even today there exists significant variation in feeding protocols for extremely premature infants, though most regimens include conservative advancements for the smallest and sickest patients.

Human milk feedings for premature infants were advocated in the 1950’s and 1960’s, though most of the studies suggesting their benefit were retrospective and case-control in design. The most definitive report was published by Lucas and Cole in 1980, and this study demonstrated that human milk reduced the risk of NEC compared to formula feeding in each specific gestational age stratum10. Further, this is the only study that randomized patients prospectively to human milk v. formula. In this analysis, because of small numbers, there was not a statistically significant reduction in NEC in randomized patients, though the trend was strongly in favor of human milk protecting against NEC (NEC incidence: 1% human milk v. 5% formula feeding, p >0.05). Nonetheless, many subsequent studies demonstrated beneficial effects of human milk on NEC, and despite the need for robust fortification to increase calories, protein, electrolytes, minerals, and vitamins for preterm infants, human milk should be, and is standard of care for the preterm infant. For patients that do not have maternal milk available, studies suggested that donor human milk may be advantageous compared to formula feedings. All studies have not been definitive, though in a recent meta-analysis, donor milk reduced the risk of NEC compared to formula feedings. (reference)

For many years, fortification of human milk has been provided by concentrated bovine-based products that include high protein content, increased fat and carbohydrate, and a large array of electrolytes, minerals, and vitamins. Recently, human milk-based fortification has been developed, and a study from 2010 suggested that NEC was reduced using human milk-based fortifier compared to bovine-based fortifiers11. Though this study was not powered to evaluate NEC as the primary outcome, the data are of interest, and while a large, definitive, appropriately powered study would be worthwhile, it remains unclear as to the mechanism responsible for this possible impact. Previous studies have shown that human milk reduces the risk of NEC in a dose-dependent manner, and suggest that many bioactive factors in human milk (that are not present or lower in preterm formula), such as leukocytes, polyunsaturated fatty acids, oligosaccharides, immunoglobulins such as IgA, lactoferrin, commensal microbes, and many others could provide antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory protection for the immune-compromised host. Alternatively, it has been suggested that cow’s milk protein from the bovine-based fortification could initiate an inflammatory response and intestinal necrosis as part of the NEC cascade. This mechanism has been suggested in human observations in which peripheral blood monocytes from NEC patients respond with more inflammatory mediator production following bovine lactoglobulin compared to preterm monocytes that have normal intestinal health (reference). Nonetheless, it is known that human milk protein content includes approximately 10% of cow’s milk proteins from women who are not on a dairy free diet, so the possible impact of human milk fortification and cow’s milk protein exposure at this stage remains conjectural.

In summary, enteral feedings may contribute to the initiation of NEC, and while the understanding of these risk factors changed over the last 30–40 years, specific strategies and feeding protocols are not uniformly agreed upon by all clinicians.

EFFECT OF MICROBIOME

It was suggested over 50 years ago that bacteria contributed significantly to the development of NEC. Mizrahi and colleagues in NYC cultured blood and peritoneal fluid from patients with disease and demonstrated a predilection for Gram negative bacteria, particularly E. Coli as offending agents associated with NEC12. Additional studies in the early 1970’s showed that ‘epidemics’ of NEC occurred in some NICU’s, and in one of the first reports, Stein et al showed that Salmonella organisms were involved in 11 consecutive cases13. Nonetheless, many cases of NEC were not associated with bacterial organisms in the blood, and further investigation suggested that intestinal bacteria might initiate NEC by activating the inflammatory response. It was suggested in the 1970’s that the intestinal microbiome in newborns housed in the NICU environment was different than in healthy full-term infants, yet clear description of microbial differences were first described between preterm infants and full-term infants by Gewolb and colleagues in 199914. These investigators cultured stool from 29 preterm infants born weighing less than 1000 grams, and showed a significant lack of diversity in the organisms as compared to full-term infants. Further, the study showed that breast milk exposed infants had more diversity, and those treated with early antibiotics had much less. Finally, results showed that only 1/29 patients had evidence of commensal bacteria compared to the majority of full-term infants who had significant quantities of these organisms in routine stool cultures. This breakthrough report set the stage for additional and intense investigation into the role of the microbiome in preterm infants and NEC, and has led to further understanding of NEC pathophysiology.

As the technology improved and analyses of microbial communities advanced to sophisticated DNA methodology, many additional studies evaluated differences in the microbiome from preterm infants and in those with NEC. The first convincing report demonstrating differences between preterm infants with NEC and preterm infants without NEC showed that NEC patients had less microbial diversity and a predominance of one of many different Gram negative enteric pathogens15. In addition, further analysis showed that preterm patients without NEC had significantly more commensal Gram positive bacteria compared to the NEC patients. While many additional reports have confirmed these differences, some did not identify significant changes in patients who went on to develop NEC. In the largest prospective trial to date, Warner and colleagues evaluated 166 patients with 46 developing NEC, and they found that NEC patients had increasing amounts of Proteobacteria species prior to the onset of disease with decreasing numbers of Negativicutes and Bacilli16. These changes were prominent only in those patients less than 28 weeks gestation at birth, and there was significantly less microbial diversity in those patients who went on to develop NEC. Overall, using a modified meta-analysis approach, all studies together seemed to corroborate these important findings, and it is generally accepted that changes in the composition of intestinal microbes contribute to the development of NEC17.

Based on the supposition that the microbiome contributes to NEC and that preterm infants have a modified microbiome with less commensal species, more Gram negative enterics, and less overall diversity, many studies have focused on the potential impact of probiotic supplementation as a preventive strategy for the disease. In the 1990’s, two animal studies demonstrated that probiotic supplementation reduced the risk of NEC in newborn quail and rodent models, and subsequent clinical trials were therefore performed in high risk premature infants18,19. There have now been a large number of trials, though most are underpowered and utilize various combinations of organisms. However, the recent meta-analyses demonstrate significant reduction in the incidence of NEC20. With increasing numbers of studies, the effect size for the impact of probiotics is lower, though there remains obvious excitement in the neonatal community about the potential efficacy of this simple approach to prevent NEC. Further quality control, safety, and efficacy studies are ongoing in the US before routine standard of care is initiated using this approach.

INFLAMMATION AND NEC

For many years, the pathogenesis of NEC was thought to be multifactorial and occurred in response to several key risk factors of prematurity, enteral feeding, intestinal ischemia, and bacterial effects21. In addition, it was suggested in the 1960’s and 1970’s that these risk factors stimulated an inflammatory response that either localized in the intestine, or could become more systemic in more severe cases of NEC. In early reports, it was suggested that bacterial products such as endotoxin (also known as lipopolysaccharide or LPS) were associated with NEC and that these cell wall ligands initiated the inflammatory response leading to intestinal necrosis. At the time, a limited number of inflammatory mediators were well described and understood, though studies suggested the potential role of prostaglandin analogues such as thromboxanes and leukotrienes.

In 1979, platelet activating factor (PAF) was discovered, and this endogenous phospholipid mediator was shown to initiate potent inflammatory responses in a variety of tissues including the intestine22. In 1983, Gonzalez-Crussi and Hsueh demonstrated that PAF infusions into adult rats resulted in severe intestinal necrosis with limited pathology in the other organs23. Subsequently, these investigators showed that PAF receptor antagonists prevented hypoxia and LPS-induced intestinal injury, and that PAF content was elevated in intestinal tissue recovered from animals with intestinal inflammation. Caplan and others reproduced these studies in a neonatal rat model of NEC, and showed that PAF receptor antagonists and the PAF-degrading enzyme, PAF-acetylhydrolase decreased the incidence of disease24,25. Further, they showed that preterm infants with NEC had higher PAF levels and lower PAF-acetylhydrolase activity compared to gestational age-matched controls26. These results together identified an important central role of PAF in intestinal inflammation and NEC in the newborn environment.

BACTERIAL-ENTEROCYTE SIGNALING IN THE PATHOGENESIS NEC?

The role for bacteria in the pathogenesis of NEC is highlighted by several clinical and experimental observations. First, NEC typically develops at several weeks of age, corresponding to the time at which bacterial colonization develops27–29. Second, the administration of antibiotics is used as a treatment for NEC especially in its early stages, consistent with the notion that bacterial signaling may play a role in driving its development towards more advanced stages30. Third, patients with NEC may demonstrate growth of enteric organisms in the blood, as well as elevated levels of LPS (a cell wall component of Gram negative bacteria), suggestive that a breakdown of the intestinal barrier and egress of bacteria into the circulation occurs during the course of the disease31,32. Given that the disease process in NEC is initiated in the intestines – in contradistinction to other septic conditions in infants in which remote infection may lead to secondary intestinal pathology – we and others have proposed that one of the earliest events that lead to the development of NEC involve abnormal signaling in the premature intestine in response to colonizing microbes. We will now consider how abnormal bacterial-intestinal signaling plays a central role in the pathogenesis of NEC, and how strategies to disrupt abnormal bacterial-intestinal signaling can potentially prevent or treat this disease.

In seeking to understand the role of bacterial signaling in the pathogenesis of NEC, we also seek to address several key questions in the field, as follows:

What is it about the premature intestinal epithelium that predisposes the host to the development of NEC in the first place?

Why does the intestinal mucosa actually die – as opposed to simply becoming extremely inflamed – in the pathogenesis of NEC?

What explains the fact that breast milk is so often protective against the development of NEC?

What explains the reasons for which one individual patient may develop NEC, while another infant, born at the same gestational age and housed in the same NICU, does not develop NEC?

By addressing each of these questions in turn, and placing the potential responses within the historical context described above, we seek to not only gain a greater understanding of the pathogenesis of NEC, but also to develop novel and specific therapies for these patients.

BACTERIAL SIGNALING IN THE PREMATURE HOST LEADS TO NEC.

Several investigators have focused on elucidating the mechanisms by which bacterial signaling occurs in the premature host, and how abnormal bacterial signaling can lead to the development of NEC. One of the most exciting discoveries in this regard was the identification of the role of the Toll-like receptors as pathogen recognition molecules that allow the host to respond to potential pathogens – including bacteria – without ever having seen them before. The first family member identified – toll like receptor 4 - (TLR4) recognizes LPS, and induces a pro-inflammatory response involving the activation of the cytokine inducing transcription factor NFkB33. Caplan’s group showed in 2006 for the first time that mice deficient in TLR4 were protected from NEC development34, providing the first evidence for TLR4 in the pathogenesis of NEC, and more importantly, providing proof that bacterial-enterocyte signaling plays a role in this disease. In additional independent studies published in 2007, Hackam and colleagues showed that expression of TLR4 was higher in the intestine of mice and humans with NEC as compared with mice without NEC, and showed that a different strain of TLR4 deficient mice were protected from the development of this disease35,36. Furthermore, in a series of additional studies, Hackam and colleagues showed that TLR4 signaling in the intestinal epithelium as opposed to other cells is required for the development of NEC in mice, as mice lacking TLR4 on the intestinal epithelium were protected from NEC37.

In seeking to understand the mechanisms by which TLR4 activation leads to NEC, Hackam and colleagues further showed that TLR4 signaling on the intestinal epithelium led to increased cell death via an induction of endoplasmic reticulum and enterocyte apoptosis, as well as a reduction in mucosal repair via inhibition of enterocyte migration and enterocyte proliferation38,39. These deleterious effects of TLR4 on the intestinal mucosa result in mucosal breakdown and bacterial translocation, and the septic picture that characterizes NEC. It is noteworthy that the clinical factors most often seen in association with NEC, including hypoxia, remote infection, and prematurity, are all associated with induced TLR4 expression in the intestine, suggesting a biologic explanation for these clinical observations. The principal findings that the LPS recognition molecule TLR4 is elevated in experimental and human NEC, and that it plays a key role in the pathogenesis of this disease, has been confirmed by a variety of investigators40,41,42,43,44,45.

In seeking to gain a greater understanding of the role of TLR4 in the premature intestine, Hackam and others have performed in situ hybridization studies using mRNA probes for TLR4, and note that TLR4 is expressed specifically on the intestinal progenitor cells (stem cells) within the crypts46,47. It was further determined that TLR4 is expressed at higher levels in the premature as compared with the full term host, which reflects in part the role of TLR4 in the regulation of normal stem cell function, as TLR4 was found to be an important regulator of Notch signaling in the stem cells of the gut35–37,46,48. As a result, the premature host, in whom the intestine is normally still developing and expresses very high levels of TLR4, is at particularly higher risk for NEC development when exposed to bacteria within the harsh, bacteria rich extra-uterine environment of the neonatal intensive care unit. These findings provide insights into why the premature infant is at risk for NEC development, and why bacterial intestinal signaling is so much higher in the premature as compared with the full term population. These findings were explored in greater detail in a recent review from the Hackam group49.

Recent studies have shed light on the cells that migrate to the inflamed intestinal mucosa of the premature infant, leading to the development of NEC. Several labs have shown that the development of NEC is characterized by an influx of pro-inflammatory lymphocytes, while Hackam and colleagues have determined that NEC is characterized by a TLR4-mediated influx of pro-inflammatory Th17 lymphocytes and a loss of anti-inflammatory T regulatory lymphocytes in the newborn mucosa. The influx of Th17 lymphocytes was sufficient for NEC development, as the adoptive transfer of these inflammatory cells into naïve mice resulted in the development of spontaneous NEC-like injury in the recipient intestinal mucosa50. Importantly, strategies that either block the influx of Th17 cells, or which promoted the induction of anti-inflammatory Treg cells such as the administration of all trans retinoic acid, resulted in significant NEC protection in experimental studies50. Taken together, these findings explain in part the effector mechanisms by which TLR4 responses to bacterial signaling cause the profound inflammation observed in the premature intestine in the pathogenesis of NEC, and provide a rationale for further study of bacterial signaling in order to prevent this disease.

MECHANISMS OF INTESTINAL DEATH IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF NEC.

While the above findings explain the mechanisms by which bacterial intestinal signaling in the premature host may lead to inflammation as seen in NEC, additional findings explain the mechanisms that underlie the tissue death that is characteristic of this disease. Specifically, as noted above, TLR4-mediated bacterial signaling leads to increased mucosal injury and reduced mucosal repair, resulting in mucosal defects through which enteric organisms can readily translocate into the circulation in the setting of prematurity39,51. Upon entering the circulation, bacteria then interact with TLR4 on the lining of the mesenteric blood vessels, which leads to a dramatic inhibition of expression of the major vasodilator eNOS and reduction of nitric oxide (NO), which leads to profound vasoconstriction52. The resultant dramatic decrease in intestinal perfusion explains the tissue necrosis that is the hallmark of severe NEC. Accordingly, strategies which augment nitric oxide signaling, such as provision of the nitric oxide precursor sodium nitrate, or treatment with sildenafil, restore mesenteric perfusion in experimental models and attenuate NEC severity52. These findings also provide insights into the protective mechanisms of breast milk, which was found to be especially enriched in nitric oxide precursor molecules as well as human milk oligosaccharides, both of which augment intestinal perfusion, and prevent the deleterious effects of exaggerated bacterial-intestinal signaling in the premature host in the pathogenesis of NEC52.

CURTAILING BACTERIAL SIGNALING IN THE PREMATURE INTESTINE TO PREVENT NEC: AMNIOTIC FLUID, BREAST MILK AND PROBIOTICS.

The above findings provide evidence that exaggerated bacterial signaling plays a role in the development of NEC in premature infants, and suggest the possibility that strategies may exist which curtail the degree of TLR4 signaling, and limit the propensity for NEC development. In this regard, several groups have shown that amniotic fluid administration can limit NEC38,53–62, which Hackam et al showed to be due to effects on inhibition of the degree of TLR4 signaling38. It is noteworthy that as the intestinal mucosa of the developing fetus is bathed in swallowed amniotic fluid and TLR4 activation is restricted, the fetus is protected from unexpected activation of TLR4 by ascending bacteria in utero, which could otherwise lead to intestinal injury and premature birth. The protective effects of amniotic fluid were found to be attributable to the high concentrations of epidermal growth factor (EGF) which limit TLR4 signaling via activation of inhibitory p38 MAPK pathways38.

In additional studies, breast milk was determined to serve as a powerful inhibitor of TLR4 signaling, again through the rich concentration of EGF that is secreted by the mammary gland into the breast milk particularly in the first weeks of life63. Removal of EGF from breast milk or administration of exogenous mouse breast milk to mice lacking the EGF receptor significantly attenuated the protective benefits of breast milk, confirming that EGF is the key protective factor in breast milk responsible for TLR4 inhibition63, and which may explain by extension the profound protection that breast milk offers against NEC development in premature infants.

Additional studies have shown that probiotic bacterial DNA can significantly inhibit TLR4 signaling in the developing intestine of mice and piglets, providing a potential explanation for the protective benefits of probiotics observed against NEC in infants36. It is noteworthy that the DNA of probiotic bacteria – which differs structurally from mammalian DNA – was sufficient to inhibit TLR4, suggesting that live bacteria may not be required to achieve the benefit of probiotics64. In exploring the mechanisms involved, probiotic bacterial DNA was found to activate TLR9, a homologous receptor to TLR4 which recognizes bacterial DNA, and inhibits TLR4 through activation of the inhibitory molecule IRAK-m36,64,65.

Taken together, these findings provide evidence that while bacterial signaling may lead to NEC, several natural biological mechanisms exist to limit the degree of TLR4 signaling and thus attenuate bacterial recognition, leading to NEC protection. Such findings raise the possibility that pharmacologic approaches to limit TLR4 activation by endogenous bacteria may provide novel approaches to the prevention or treatment of NEC as explored further below.

PHARMACOLOGIC INHIBITION OF TLR4 FOR THE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF NEC

Having shown a critical role for bacterial signaling in the pathogenesis of NEC through activation of the LPS receptor TLR4, we and others have sought to identify whether pharmacologic inhibition of TLR4 may represent a novel approach for the prevention or treatment of NEC. To do so, the Hackam laboratory performed an in silico screen of potential binding partners to the LPS docking site within TLR4, based upon the recently published crystal structure of this molecule66,67. This screen yielded many potential hits, of which approximately 80 were then verified using in vivo models of mouse endotoxemia. This secondary screen then confirmed a lead compound, which was provisionally entitled C34, which is a 2-acetamidopyranoside (MW 389) with the formula C17H27NO9 that fits into the internal pocket of TLR4. C34 was found to inhibit TLR4 in vivo, and in human ileum ex vivo that had been resected from infants with NEC, suggesting the possibility of effectiveness in humans. Interestingly, structurally related molecules to C34 was shown to be present in breast milk, thereby suggesting an additional mechanism by which breast milk inhibits TLR4 activation and thus prevents NEC66,67. Supplementation of infant formula with C34 prevented experimental NEC in animal models, raising the possibility that a clinical developmental strategy could be developed based upon TLR4 inhibition using compounds like C34.(reference)

POTENTIAL MULTI-AGENT APPROACHES FOR NEC PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Based upon the above understanding of the role of bacterial signaling in the pathogenesis of NEC, a variety of potential molecular approaches could be proposed for the prevention or treatment of NEC, using a strategy of TLR4 inhibition. Such approaches may include inhibition of the upstream TLR4 signaling pathways using C34 or other novel and potentially more potent analogues, or the administration of probiotic bacteria or probiotic DNA, which serve to limit TLR4 activation via effects on TLR9. The administration of agents capable of bypassing the deleterious effects of exaggerated TLR4 signaling, which may include nitric oxide precursors to enhance intestinal perfusion, or growth factors that either promote intestinal healing or act to further limit downstream TLR4 signaling responses, could be utilized in combination as a supplement to human milk feeding. Such an approach would essentially represent “the surfactant of the gut” by developing a strategy capable of promoting an adaptive response to bacterial colonization of the premature intestine, and thus limit the deleterious effects of exaggerated bacterial signaling that can lead to the development of NEC.

SUMMARY

Necrotizing enterocolitis has caused significant morbidity and mortality in neonatal units for many years, and the historical context provides an interesting variety of scientific insights. As the pathogenesis of NEC has become better understood, our recent findings on the role of bacterial signaling in the pathogenesis of NEC suggest possible answers to the questions posed above regarding the epidemiology of this disease. Specifically, it appears that the premature intestinal epithelium is at particular risk for the development of NEC in part due to the elevated expression of TLR4 within the premature as compared with the full term intestine, which is a consequence of the recently identified role for TLR4 in normal gut development, and its expression on the intestinal stem cells within the premature intestine. When the premature gut is colonized by bacteria in the postnatal period (particularly Gram-negative Proteobacteria), activation of TLR4 leads to mucosal injury, reduced mucosal repair, and bacterial translocation which then causes vasoconstriction, leading to the death of parts of the intestine, which characterizes NEC. Breast milk – a powerful protective agent for NEC – is endowed with molecules that inhibit TLR4 signaling, including growth factors such as EGF, but also novel oligosaccharides similar to our recently identified TLR4 inhibitor, C34. These factors lead us to speculate that differences in the susceptibility to the development of NEC between individual patients may lie in part in genetic alterations in TLR4 signaling pathways, or in those pathways which serve to normally restrain TLR4 signaling from leading to disease.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Based in part on early successes in the understanding of the role of bacterial signaling in NEC pathogenesis, there is reason to be optimistic that the field of NEC research is poised to enter a period of significant advancement towards the ultimate goal of developing a specific cure for this disease. To accomplish this goal, we will need to understand with greater accuracy which patients are most susceptible to the development of NEC; this will likely require the identification of specific genetic and molecular biomarkers. Such a strategy may allow physicians to tailor specific anti-NEC therapies to individual patients, such as providing anti-TLR4 agents for those with exaggerated TLR4 levels above a certain threshold. It is likely that additional emphasis on NEC prevention – perhaps through a greater understanding of how and when to feed premature infants, in combination with probiotic mediated manipulation of the microbial environment – may offer additional advances in the care of these fragile patients. Through careful and focused research, we hope to finally offer a specific cure to patients and families whose premature infants develop this devastating disease.

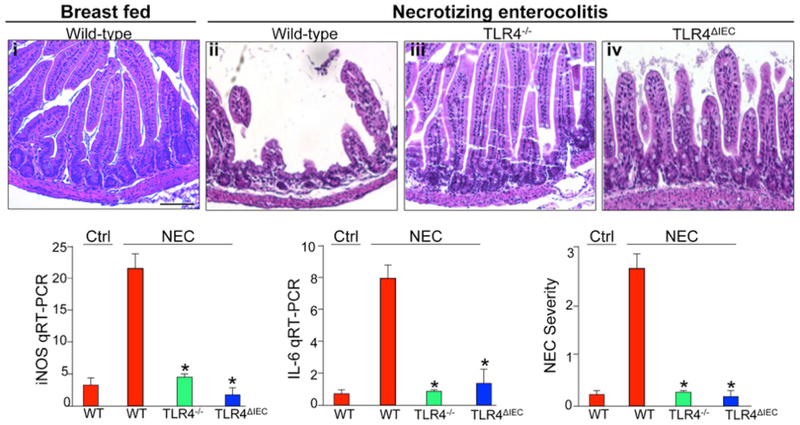

Figure 1. The development of necrotizing enterocolitis requires TLR4 activation on the intestinal epithelium.

i-iv: epresentative H&E micrographs from sections of the terminal ileum in mice without (i) or with (ii-iv) NEC that are either wild-type (i-ii), globally deficient in TLR4 (iii), or lacking TLR4 on the intestinal epithelium (iv). Shown also is the expression by RT-PCR of iNOS and IL-6, and NEC severity in the indicated groups. Reproduced with permission from Gastroenterology 2012 Sep;143(3).

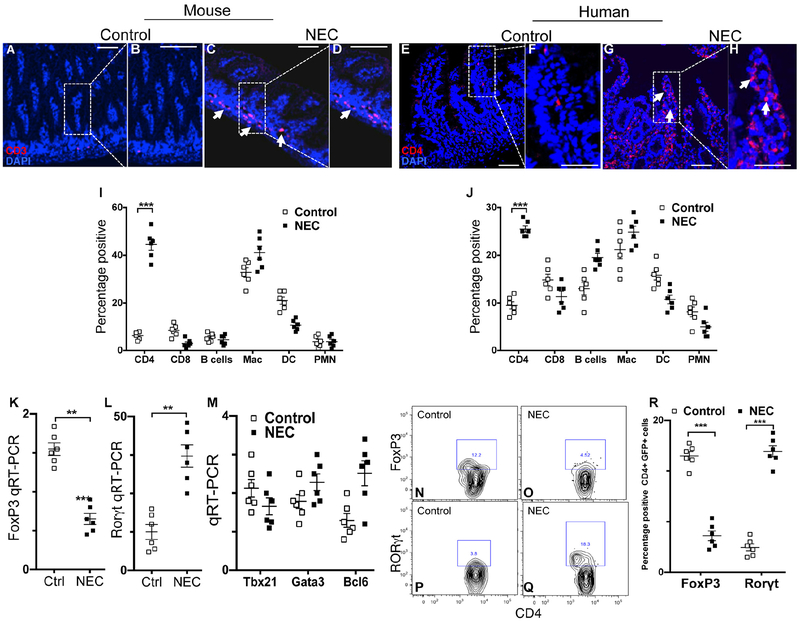

Figure 2. The development of necrotizing enterocolitis is associated with induction of Th17 cells and reduction in Tregs in the newborn intestine of mice and humans.

A-H: Representative confocal micrographs from sections of the terminal ileum in mice (A-D) and human infant (B-H) with or without NEC, immunostained for CD3 or CD4 as indicated. Characterization of the immune cell infiltrate in the lamina propria in mouse (I) and human (J) is shown. Scale bar = 10mm. K-M: qRT-PCR expression of the lamina propria CD4+ T cells in mice with and without NEC for the indicated lymphocyte transcription factors in murine CD4+ T cells. N-R: Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3+ (N-O) or RORgt+ (P-Q) cells in the lamina propria of mice with and without NEC; quantification is shown in R. Reproduced from Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2016 Feb;126(2):495–508.

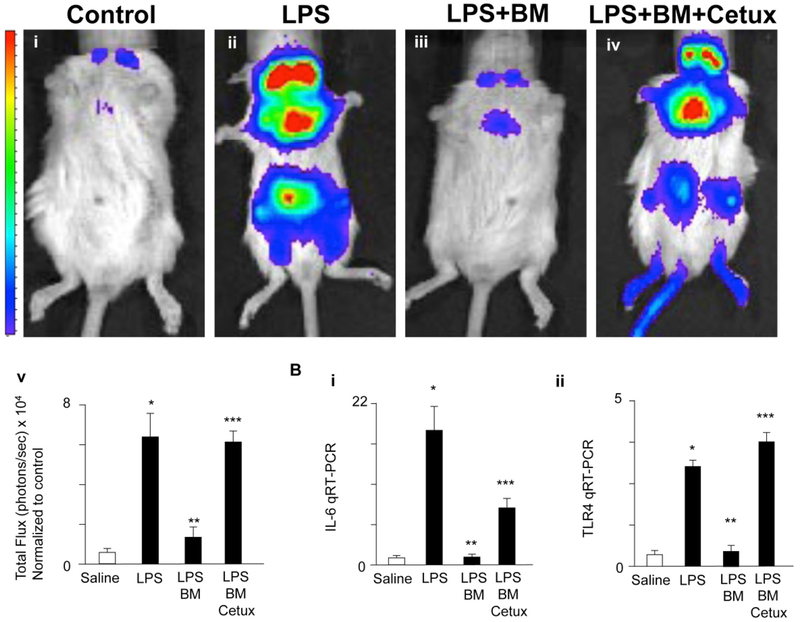

Figure 3. Breast milk attenuates TLR4 signaling in vivo via EGFR.

A: Pseudocolor images demonstrating whole animal NF-κB luciferase activity treated with either saline (i), LPS (5 mg/kg, 6 hr, ii), gavage pretreatment with breast milk (50 μL/gram body weight, iii) and/or cetuximab (Cetux), an EGFR inhibitor (100 μg/day for 3 days, iv) 1 h prior to LPS administration, quantification of images in Total Flux (photons/sec × 104, v). B: IL-6 (i) and TLR4 mRNA expression (ii) for above groups. *p<0.05 versus saline (white bar), **p<0.05 versus LPS, ***p<0.05 versus LPS + breast milk (BM). Data are mean ±SD. Representative of at least three separate experiments with at least three mice per group. Reproduced with permission from Mucosal Immunol. 2015 Sep;8(5):1166–79.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frost BL, Modi BP, Jaksic T, Caplan MS. New Medical and Surgical Insights Into Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Review. JAMA pediatrics 2017;171:83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid KO. [A specially severe form of enteritis in newborn, enterocolitis ulcerosa necroticans. I. Pathological anatomy.]. Z Kinderheilkd 1952;8:114–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow B, Santulli TV. Importance of multiple episodes of hypoxia or cold stress on the development of enterocolitis in an animal model. Surgery 1975;77:687–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitt J, Barlow B, Heird WC. Protection against experimental necrotizing enterocolitis by maternal milk. I. Role of milk leukocytes. Pediatr Res 1977;11:906–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown EG, Sweet AY. Preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates. JAMA 1978;240:2452–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn L, Hulman S, Weiner J, Kliegman R. Beneficial effects of early hypocaloric enteral feeding on neonatal gastrointestinal function: preliminary report of a randomized trial. J Pediatr 1988;112:622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slagle TA, Gross SJ. Effect of early low-volume enteral substrate on subsequent feeding tolerance in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 1988;113:526–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berseth CL, Bisquera JA, Paje VU. Prolonging small feeding volumes early in life decreases the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2003;111:529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan J, Young L, McGuire W. Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas A, Cole TJ. Breast milk and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis [see comments]. Lancet 1990;336:1519–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan S, Schanler RJ, Kim JH, et al. An exclusively human milk-based diet is associated with a lower rate of necrotizing enterocolitis than a diet of human milk and bovine milk-based products. J Pediatr 2010;156:562–7 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizrahi A, Barlow O, Berdon W, Blanc WA, Silverman WA. Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Premature Infants. J Pediatr 1965;66:697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein H, Beck J, Solomon A, Schmaman A. Gastroenteritis with necrotizing enterocolitis in premature babies. Br Med J 1972;2:616–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gewolb IH, Schwalbe RS, Taciak VL, Harrison TS, Panigrahi P. Stool microflora in extremely low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1999;80:F167–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Hoenig JD, Malin KJ, et al. 16S rRNA gene-based analysis of fecal microbiota from preterm infants with and without necrotizing enterocolitis. ISME J 2009;3:944–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner BB, Deych E, Zhou Y, et al. Gut bacteria dysbiosis and necrotising enterocolitis in very low birthweight infants: a prospective case-control study. Lancet 2016;387:1928–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pammi M, Cope J, Tarr PI, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis in preterm infants preceding necrotizing enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microbiome 2017;5:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butel MJ, Roland N, Hibert A, et al. Clostridial pathogenicity in experimental necrotising enterocolitis in gnotobiotic quails and protective role of bifidobacteria. J Med Microbiol 1998;47:391–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caplan MS, Miller-Catchpole R, Kaup S, et al. Bifidobacterial supplementation reduces the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in a neonatal rat model. Gastroenterology 1999;117:577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aceti A, Gori D, Barone G, et al. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Pediatr 2015;41:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kliegman RM, Fanaroff AA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med 1984;310:1093–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benveniste J, Nunez D, Duriez P, Korth R, Bidault J, Fruchart JC. Preformed PAF-acether and lyso PAF-acether are bound to blood lipoproteins. FEBS Lett 1988;226:371–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-Crussi F, Hsueh W. Experimental model of ischemic bowel necrosis. The role of platelet-activating factor and endotoxin. American Journal of Pathology 1983;112:127–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caplan MS, Hedlund E, Adler L, Lickerman M, Hsueh W. The platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist WEB 2170 prevents neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis in rats. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1997;24:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caplan MS, Lickerman M, Adler L, Dietsch GN, Yu A. The role of recombinant platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase in a neonatal rat model of necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res 1997;42:779–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caplan MS, Hsueh W. Necrotizing enterocolitis: role of platelet activating factor, endotoxin, and tumor necrosis factor. J Pediatr 1990;117:S47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brower-Sinning R, Zhong D, Good M, et al. Mucosa-associated bacterial diversity in necrotizing enterocolitis. PLoS One 2014;9:e105046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costello EK, Carlisle EM, Bik EM, Morowitz MJ, Relman DA. Microbiome assembly across multiple body sites in low-birthweight infants. mBio 2013;4:e00782–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlisle EM, Morowitz MJ. The intestinal microbiome and necrotizing enterocolitis. Curr Opin Pediatr 2013;25:382–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackwood BP, Hunter CJ, Grabowski J. Variability in Antibiotic Regimens for Surgical Necrotizing Enterocolitis Highlights the Need for New Guidelines. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2017;18:215–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duffy LC, Zielezny MA, Carrion V, et al. Concordance of bacterial cultures with endotoxin and interleukin-6 in necrotizing enterocolitis. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duffy LC, Zielezny MA, Carrion V, et al. Bacterial toxins and enteral feeding of premature infants at risk for necrotizing enterocolitis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2001;501:519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Innate sensors of microbial infection. Journal of clinical immunology 2005;25:503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jilling T, Simon D, Lu J, et al. The roles of bacteria and TLR4 in rat and murine models of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Immunol 2006;177:3273–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leaphart CL, Cavallo JC, Gribar SC, et al. A critical role for TLR4 in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis by modulating intestinal injury and repair. J Immunol 2007;179:4808–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gribar SC, Sodhi CP, Richardson WM, et al. Reciprocal expression and signaling of TLR4 and TLR9 in the pathogenesis and treatment of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Immunol 2009;182:636–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sodhi CP, Neal MD, Siggers R, et al. Intestinal epithelial Toll-like receptor 4 regulates goblet cell development and is required for necrotizing enterocolitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2012;143:708–18 e1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Good M, Siggers RH, Sodhi CP, et al. Amniotic fluid inhibits Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in the fetal and neonatal intestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:11330–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neal MD, Sodhi CP, Dyer M, et al. A critical role for TLR4 induction of autophagy in the regulation of enterocyte migration and the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Immunol 2013;190:3541–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolfs TG, Buurman WA, Zoer B, et al. Endotoxin induced chorioamnionitis prevents intestinal development during gestation in fetal sheep. PLoS One 2009;4:e5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nanthakumar N, Meng D, Goldstein AM, et al. The mechanism of excessive intestinal inflammation in necrotizing enterocolitis: an immature innate immune response. PLoS One 2011;6:e17776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou W, Li W, Zheng XH, Rong X, Huang LG. Glutamine downregulates TLR-2 and TLR-4 expression and protects intestinal tract in preterm neonatal rats with necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg 2014;49:1057–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng D, Zhu W, Shi HN, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 in human and mouse colonic epithelium is developmentally regulated: a possible role in necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res 2015;77:416–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng PC, Chan KY, Leung KT, et al. Comparative MiRNA Expressional Profiles and Molecular Networks in Human Small Bowel Tissues of Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Spontaneous Intestinal Perforation. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quintanilla HD, Liu Y, Fatheree NY, et al. Oral administration of surfactant protein-a reduces pathology in an experimental model of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015;60:613–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neal MD, Sodhi CP, Jia H, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is expressed on intestinal stem cells and regulates their proliferation and apoptosis via the p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2012;287:37296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afrazi A, Branca MF, Sodhi CP, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress in intestinal crypts induces necrotizing enterocolitis. J Biol Chem 2014;289:9584–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sodhi CP, Shi XH, Richardson WM, et al. Toll-like Receptor-4 Inhibits Enterocyte Proliferation via Impaired beta-Catenin Signaling in Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Gastroenterology 2010;138:185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nino DF, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ. Necrotizing enterocolitis: new insights into pathogenesis and mechanisms. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology 2016;13:590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Egan CE, Sodhi CP, Good M, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated lymphocyte influx induces neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Clin Invest 2016;126:495–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu P, Sodhi CP, Jia H, et al. Animal models of gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Animal models of necrotizing enterocolitis: pathophysiology, translational relevance, and challenges. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2014;306:G917–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yazji I, Sodhi CP, Lee EK, et al. Endothelial TLR4 activation impairs intestinal microcirculatory perfusion in necrotizing enterocolitis via eNOS-NO-nitrite signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:9451–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siggers J, Ostergaard MV, Siggers RH, et al. Postnatal amniotic fluid intake reduces gut inflammatory responses and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm neonates. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013;304:G864–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Good M, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ. Evidence-based feeding strategies before and after the development of necrotizing enterocolitis. Expert review of clinical immunology 2014;10:875–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jain SK, Baggerman EW, Mohankumar K, et al. Amniotic fluid-borne hepatocyte growth factor protects rat pups against experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2014;306:G361–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ostergaard MV, Bering SB, Jensen ML, et al. Modulation of intestinal inflammation by minimal enteral nutrition with amniotic fluid in preterm pigs. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014;38:576–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stenson WF. Preventing necrotising enterocolitis with amniotic fluid stem cells. Gut 2014;63:218–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zani A, Cananzi M, Lauriti G, et al. Amniotic fluid stem cells prevent development of ascites in a neonatal rat model of necrotizing enterocolitis. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2014;24:57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ostergaard MV, Shen RL, Stoy AC, et al. Provision of Amniotic Fluid During Parenteral Nutrition Increases Weight Gain With Limited Effects on Gut Structure, Function, Immunity, and Microbiology in Newborn Preterm Pigs. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:552–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dasgupta S, Jain SK. Protective effects of amniotic fluid in the setting of necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCulloh CJ, Olson JK, Wang Y, Vu J, Gartner S, Besner GE. Evaluating the efficacy of different types of stem cells in preserving gut barrier function in necrotizing enterocolitis. J Surg Res 2017;214:278–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.MohanKumar K, Namachivayam K, Ho TT, Torres BA, Ohls RK, Maheshwari A. Cytokines and growth factors in the developing intestine and during necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Perinatol 2017;41:52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Good M, Sodhi CP, Egan CE, et al. Breast milk protects against the development of necrotizing enterocolitis through inhibition of Toll-like receptor 4 in the intestinal epithelium via activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mucosal Immunol 2015;8:1166–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Good M, Sodhi CP, Ozolek JA, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 decreases the severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in neonatal mice and preterm piglets: evidence in mice for a role of TLR9. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2014;306:G1021–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sodhi C, Richardson W, Gribar SC, Hackam DJ. The development of animal models for the study of necrotizing enterocolitis. Dis Model Mech 2008;1:94–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neal MD, Jia H, Eyer B, et al. Discovery and validation of a new class of small molecule Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) inhibitors. PLoS One 2013;8:e65779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wipf P, Eyer BR, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Synthesis of -inflammatory alpha-and beta-linked acetamidopyranosides as inhibitors of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). Tetrahedron letters 2015;56:3097–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]