Abstract

G-protein coupled estrogen receptor, Gper1, has been implicated in cardiovascular disease, but its mechanistic role in blood pressure control is poorly understood. Here we demonstrate that genetically salt-sensitive hypertensive rats with complete genomic excision of Gper1 by a multiplexed gRNA CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats)/Cas9 (CRISPR Associated Protein) approach, present with lower blood pressure, which was accompanied by altered microbiota, different levels of circulating short chain fatty acids, and improved vascular relaxation. Microbiotal transplantation from hypertensive Gper1+/+ rats reversed the cardiovascular protective effect exerted by the genomic deletion of Gper1. Thus, this study reveals a role for Gper1 in promoting microbiotal alterations that contribute to cardiovascular pathology. However, the exact mechanism by which Gper1 regulates BP is still unknown. Our results indicate that the function of Gper1 is contextually dependent on the microbiome, whereby, contemplation of using Gper1 as a target for therapy of cardiovascular disease requires caution.

Keywords: Gper1, blood pressure, CRISPR/Cas9, knock out, hypertension, microbiome, SCFAs

Introduction

G-protein coupled receptors (GPRs) are increasingly being recognized with newer roles in blood pressure (BP) regulation due to their function as receptors for microbiotal metabolites such as short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) 1,2. To date, there are five GPRs discovered as modulators of BP via binding to specific SCFAs. The G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (Gper1) is a relatively recently discovered GPRs which belongs to the rhodopsin-like receptor super family 3,4. Originally categorized as an orphan receptor 5, Gper1 is now recognized as a receptor for two ligands, estrogen 6–9 and aldosterone 10–12. Due to the feature of Gper1 being an estrogen receptor, the context for research on Gper1 was originally focused on cancer. Several studies have shown that disturbances in Gper1 expression are associated with development of breast, endometrial and prostate cancer 13–15, and roles of Gper1 in the nervous system are also emerging 16.

Identification of aldosterone as a second ligand prompted studies of Gper1 in BP regulation. Recent evidence suggests that some of the vasodilator effects of Gper1 are triggered through aldosterone-dependent stimulation of the receptor 10–12. Pharmacological activation of Gper1 in rats has a lowering effect or no effect on BP 17,18, however, Gper1 knockout mouse models have demonstrated both increasing and decreasing effects on BP 9,19. Given these conflicting reports, coupled with the discovery of several GPCRs as sensors of microbial metabolites, we hypothesized that the involvement of Gper1 in the regulation of cardiovascular disease may be contextually dependent on the microbiome of the animal model. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effect of deletion of Gper1 on the BP of the Dahl Salt-Sensitive (S) rat model, whose genome is highly permissive for the development of hypertension, and whose microbiome has already been studied 20.

Methods

All data and materials will be made publicly available at the Rat Genome Database.

Animals and diet:

All animal procedures and protocols used in this report were approved by the University of Toledo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and discussed in detail in the online supplement (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Generation of a CRISPR/Cas9 mediated Gper1−/− rat:

Several guide RNAs (gRNAs) were designed to target the 5’ and 3’ ends of rat Gper1 (NM_133573.1; Genome Engineering and iPSC Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO). This method is discussed in detail in the online supplement.

Gper1 expression in heart homogenates:

To ensure that Gper1 homozygous gene deletion resulted in loss of Gper1 mRNA in homozygous rats, mRNA from heart tissue of Gper1 homozygous mutants and wild-type S rats was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies), and cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription with SuperScript III (Invitrogen) using an OligodT primer. The cDNA samples were PCR amplified using Gper1 exon–specific primers (sense 5′CAGCAATATGTGATCGCTCTCT3′ and antisense 5′AAGCTGATGTTCACCACCAA3′).

Genomic DNA isolation, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and analysis of microbiotal composition:

The fecal pellets of Gper1+/+ (n=6–7) and Gper1−/− (n=7–8) rats were collected at day 4 (before microbiota transplantation) and day 28 (after microbiota transplantation) and processed for analysis of microbial community (Wright Labs, LLC, PA), essentially as we described in 20 and in detail in the online supplement.

Targeted metabolomics profiling for SCFAs:

Serum SCFAs were quantified at Penn State Metabolomics Core Facility, University Park, PA as per previously published procedures 21,22 and described in detail in the online supplement.

Blood pressure measurements by radiotelemetry:

All wild-type (Gper1+/+) hypertensive rats and Gper1−/− rats were concomitantly bred, housed and studied to minimize environmental effects. Surgical procedures were the same as previously described by us23 and discussed in the online supplement.

Evaluation of vascular reactivity by wire-myography:

Rats were euthanized (CO2 inhalation) and the mesenteric artery was analyzed for vascular reactivity, as described in detail in the online supplement.

Microbiota transplantation:

Four week old male and female Gper1+/+ and Gper1−/− rats were implanted with C-10 radiotransmitters (Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) to record BP. After recovery from surgery (3 days) a baseline systolic BP (SBP) reading was recorded for one hour (Day 0). The resident microbiota was depleted using the protocol described previously by us 20 and described in the online supplement.

Statistical analysis:

All statistical analyses of BP studies were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5 (version 5.02). Data was analyzed by independent sample Student’s t-test or by repeated measures ANOVA as appropriate and specified in the results and figure legends. The data is presented as the mean ± standard error (Mean ± SEM). A p-value of <0.05 was used as a threshold for statistical significance.

Results

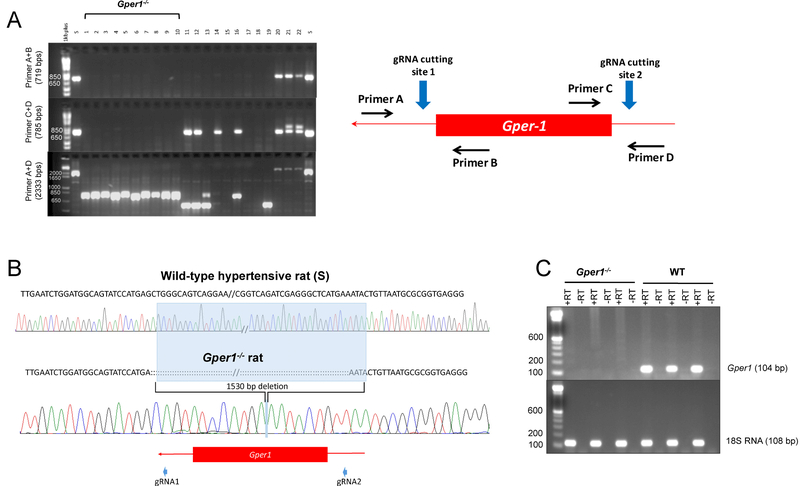

CRISPR/Cas9 based genetic ablation of Gper1

Rat Gper1 is a single exon gene with 1,128 base pairs located on rat chromosome 12 (RNO12). To ensure complete gene deletion, 2 gRNAs were designed on either end of the Gper1 gene. RNA validation performed via deletion PCR using a sense primer at the 5’end and an antisense primer at the 3’end showed a deletion PCR product of 544bps vs. wild-type PCR product of 1,484bps (Figure S1). This confirmed the efficiency of the dual gRNA approach to delete Gper1. Microinjection of 10 pseudo-pregnant rats resulted in a total of 5 homozygous founders which were used for phenotypic studies. The homozygous founders had complete deletion of Gper1 (Figure 1A) which was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Figure 1B). Homozygous founders did not express mRNA for Gper1 as demonstrated by RT-PCR (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Screening animals for CRISPR/Cas9 mediated deletion of Gper1.

(a) Representative agarose gel picture of PCR amplified tail DNA samples from pups born post-microinjection of CRISPR/Cas9 mediated deletion of Gper1. Primer A+B and C+D encompass 3’ and 5’ ends of Gper1 however Primer A+D encompasses entire gene. The inset shows schematic of position of gRNAs cutting sites and the primers used for genotyping. The first lane after DNA ladder in all three gels is wild-type S rat DNA, Animal #1 through 10 are homozygous founders which show no band in 3’ and 5’ primer ends and shorter DNA band (~750 bps) in Primer A+D compared with S band (2333 bps). (b) Representative sequencing results from the PCR products of homozygous founders shown in panel A detected 1530 bps deletion in the DNA of Gper1 mutant rats. (c) RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of Gper1 in the heart homogenate using 18S RNA as a housekeeping gene (RT- reverse transcriptase).

Microbiotal dysbiosis in Gper1+/+ rats is rectified in Gper1−/− rats.

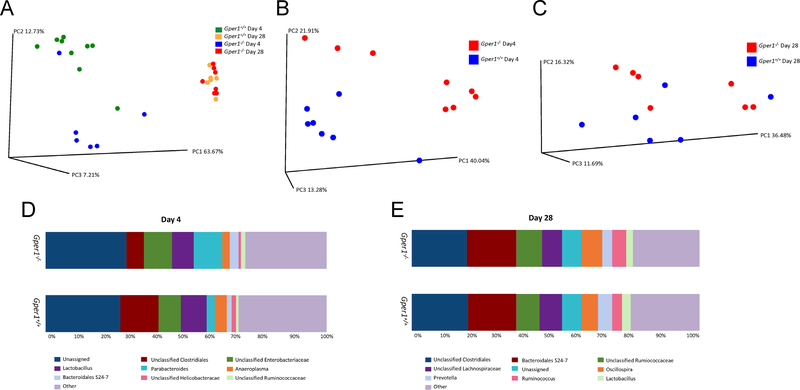

Microbiotal analysis of fecal samples of Gper1+/+ and Gper1−/− rats was performed by sequencing for the 16S rRNA gene 24. A total of 3,433,793 sequences were obtained after quality filtering and chimera picking (Table S1). Alpha-diversity analyses did not reveal differences between the two groups (data not shown). However, a beta-diversity analysis revealed distinct community structures, showing significant phylogenetic differences between fecal samples (p=0.03, ANOSIM (Analysis of Similarity) test). A PCoA plot reveals significant differences in microbial community structure between Gper1−/− and Gper1+/+ rats (Figure 5B). Figure S2 shows the relative abundance of bacterial communities in fecal samples from Gper1−/− and Gper1+/+ rats that result from taxonomic assignments of 16S rRNA gene sequences. The Parabacteroides exhibited the greatest difference between samples from Gper1−/− and Gper1+/+ rats (average relative abundance: 10.1% vs. 2.7% for Gper1−/− and Gper1+/+ cohorts, respectively; Figure S2). Bacteroidales S24–7 and unclassified enterobacteriaceae also appeared to be enriched within the Gper1−/− cohort, with 2.1% and 1.7% increases, respectively, in relative abundance in comparison to the control cohort. Gper1+/+ samples showed greater abundance of unclassified Clostridiales (7.1% increase) in comparison to the Gper1−/− cohort. Overall, a greater Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes ratio is noted in Gper1+/+ rats compared to Gper1−/− rats. Specific taxa that were enriched were identified by non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test (Tables S2 and S3).

Figure 5. Microbial sequencing in fecal samples of S and Gper1−/− rats.

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) plots at day 4 and day 28 of male rats (A). PCoA plots were used to visualize differences in weighted Unifrac distances of fecal samples from the wild-type day 4 cohort (n=9), Gper1−/− rat day 4 cohort (n=6), wild-type day 28 (n=6) and Gper1−/− rat day 28 (n=7) samples. Points clustered more closely together are more similar in terms of phylogenetic distance, whereas points that are distant from each other are phylogenetically distinct. To further observe differences in beta diversity between Gper1−/− and wild-type rats within each time-point, separate PCoA plots were generated for day 4 (B) and day 28 (C). Relative abundance plots to display differences in general microbial community structure between fecal samples collected from rats at day 4 (D) and day 28 (E).

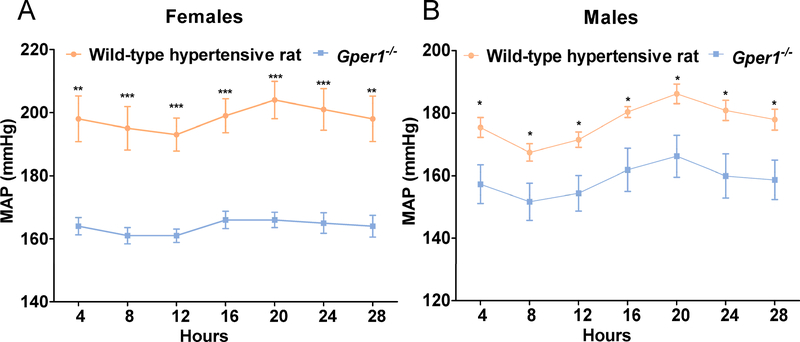

Attenuation of hypertension in Gper1−/− rats:

After 24 days on a high salt diet (2% NaCl), both Gper1−/− and Gper1+/+ rats maintained normal diurnal rhythms of systolic and diastolic BP. However, throughout the observation period, both systolic and diastolic BP, pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure in the Gper1−/− rats were all consistently and markedly lower than that in the wild-type hypertensive rats, and this effect was observed in both females and males (Figure 2A and 2B, Figure S3). Moreover, by using repeated measures ANOVA, we were able to determine that there were significant differences within the strain in regards to time for SBP, diastolic BP (DBP), pulse pressure (PP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP). Additionally, male and female Gper1−/− rats had increased body weight and nasal-anal length compared to age-matched Gper1+/+ rats (Table S4 and Figure S4). The food and fluid intake were not measured in this study.

Figure 2. Attenuation of blood pressure of Gper1−/− rats.

(A) Females, (B) Males. Radiotelemetry measurement of mean arterial pressure of wild-type hypertensive rats (n=8 females, 10 males) and Gper1−/− rats (n=7 females, 12 males). Rats were monitored for BP, 3 days after recovery from surgical implantation of radiotelemetry transmitters. Data plotted are the 4 hours moving average of recordings obtained every 5 min continuously for 24h. Levels of statistical significance for all data were analyzed by independent sample t-test. Blood pressure of Gper1−/− female and male rats was significantly lower than that of wild-type hypertensive rats.(* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)

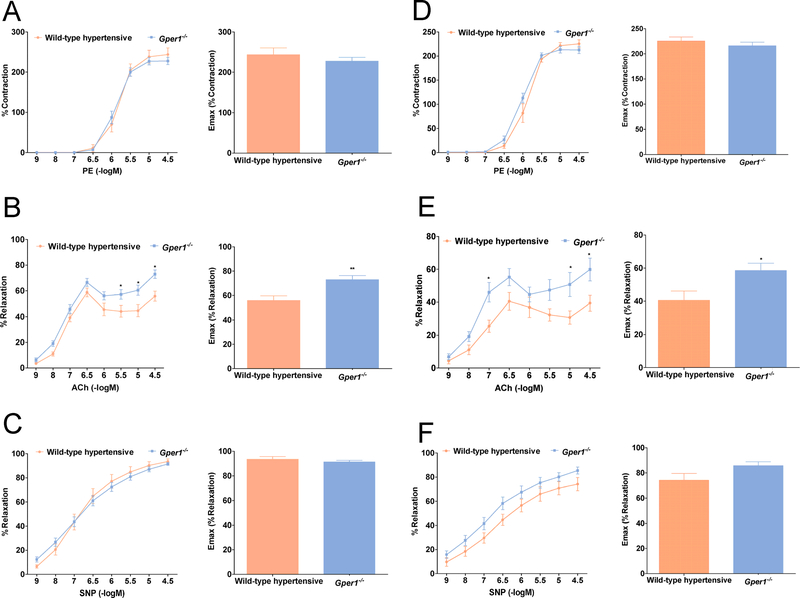

Improved vascular function in Gper1−/− rats:

Next, we examined the reactivity of secondary and tertiary order mesenteric arteries to the vasorelaxants acetylcholine (ACh) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Whereas the response of Gper1+/+ and Gper1−/− arteries to phenylephrine was indistinguishable (Figure 3A, 3D), the endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation response of mesenteric arteries from Gper1−/− rats, as measured using a cumulative dose response to ACh, was significantly higher than that of Gper1+/+ rats (Figure 3B, 3E). Importantly, the endothelium-independent relaxation induced by SNP was not affected by deletion of Gper1 (Figure 3C, 3F).

Figure 3. Gper1−/− female and male rats demonstrated superior vascular function.

Third order mesenteric arteries were dissected and mounted on wire myograph chamber. (A, D) Cumulative concentration response curve (CCRC) to phenylephrine (1nM-10μM) of mesenteric arteries was recorded from Gper1+/+ (n=12) and Gper1−/− rats (n=12). (B, E) Endothelium-dependent relaxation to ACh was assessed by adding increasing concentrations of ACh to the vessel preparation. CCRC to ACh (1nM-10μM) of mesenteric arteries was recorded from Gper1+/+ (n=9) and Gper1−/− rats (n=11). Relaxation of ACh was expressed as a percentage of level of pre-contraction induced by submaximal dose of phenylephrine. (C,F) Endothelium-independent relaxation to SNP was assessed by adding increasing concentrations of SNP to the vessel preparation. CCRC to SNP (1nM-10μM) of mesenteric arteries was recorded from Gper1+/+ (n=11) and Gper1−/− rats (n=12). Relaxation of SNP was expressed as a percentage of level of pre-contraction induced by submaximal dose of phenylephrine. The bar graphs are the maximum response recordings of respective vasoconstrictor and vasorelaxants. *p<0.05, **p<0.01

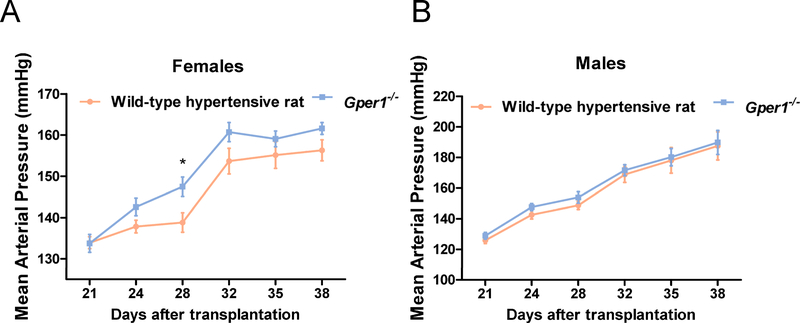

Reversal of the BP lowering effect after return of the gut microbiota in Gper1−/− rats to that of Gper1+/+ rats:

To evaluate if the differences in BP between Gper1+/+ and Gper1−/− rats could be due to alterations in gut microbiota, we subjected male and female Gper1-/- rats to a gut microbiota transplant protocol 20,25. Resident microbiota in Gper1-/- animals were depleted by antibiotic treatment and the cecal content of Gper1+/+ rats was administered by oral gavage. As a control, Gper1+/+ rats were subjected to microbiota depletion and received autologous cecal content from Gper1+/+ animals. Notably, Gper1-/- rats transplanted with cecal content from Gper1+/+ rats no longer had the BP lowering effect observed in Gper1−/− rats (Figure 4, Figure S5). By repeated measures ANOVA, there were significant increases in regards to time for each group for SBP, DBP, PP, and MAP, as expected since these rats were on a high-salt diet over the course of weeks. To ensure successful transplantation, a microbiotal analysis of fecal samples of male Gper1+/+ and Gper1−/− rats before (day 4) and after (day 28) microbiota transplantation was performed by sequencing for the 16S rRNA gene 24. Alpha- and beta-diversity analyses did not reveal differences between the two groups after transplantation (beta-diversity seen in Figure 5A). A PCoA plot revealed significant differences in microbial community structure between Gper1−/− and Gper1+/+ rats before transplantation (Figure 5B), however, not at day 28 (Figure 5C), indicating that the microbiota of Gper1−/− rats were successfully transplanted to be that of the donor Gper1+/+ animals. The conversion of the Gper1−/− gut microbiota signature to that of the donor Gper1+/+ rats was also evident at the taxa level. After microbiota transplantation, the differences in microbial community between Gper1−/− and Gper1+/+ samples were minimal (Figure 5E). Of the most prevalent taxa, only Ruminococcus showed a 1.2% increase in abundance in Gper1−/− compared to controls, whereas all remaining taxa yielded similar relative abundances between the two groups.

Figure 4. The blood pressure protecting effect in Gper1−/− rats was reversible with transplantation of cecal content from wild-type hypertensive rats.

Radio telemetry measurement of mean arterial pressure (MAP) of wild-type hypertensive rats (n= 8) and Gper1−/− rats (n=7) (females (A) and males (B)), 21 days after transplantation of cecal content of wild-type hypertensive rats. Levels of statistical significance for all data were analyzed by independent student’s t-test. *p<0.05

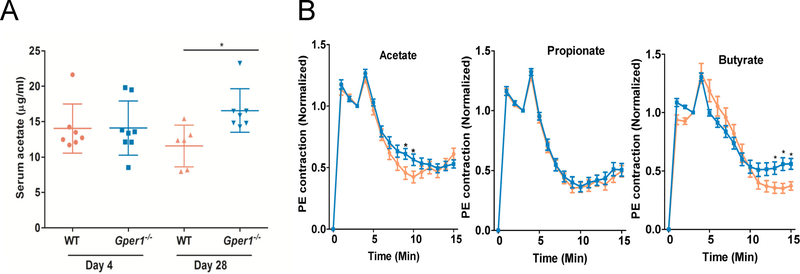

Plasma Circulating Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in Gper−/− rats:

To assess whether there were differences in SCFAs as a result of the noted alterations in the microbiota, a targeted metabolomic study of serum samples from rats pre- and post-cecal transfer was conducted. The results showed that only the circulating levels of acetate, but not propionate or butyrate (data not shown), were higher in the Gper1−/− rats given cecal content from Gper1+/+ rats (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Plasma circulating SCFAs level and vascular responses of Gper1−/− vs. wild-type rats to SCFAs. A. Serum acetate level in S and Gper1−/− rats at Day 4 and Day 28. Targeted metabolomic study demonstrated that of the three SCFAs, serum acetate level was significantly increased in the Gper1−/− rats administered with cecal content of S rats. B. Decreased relaxation of rat small mesenteric arteries (SMAs) to 5mM sodium acetate and sodium butyrate in Gper1−/− rats compared with S rats. Mean phenylephrine (10 μM) contraction amplitude measured are 1-minute time intervals and normalized to amplitude at 3 minutes. The solution was changed at 3 min to that containing short chain fatty acids. The relaxation plot for a) acetate, b) propionate and c) butyrate is shown and compared between wild-type and Gper1−/− rat SMAs.

Vascular response of Gper1−/− rats to SCFAs:

To examine whether differences exist in the vascular response of Gper1+/+ and Gper1−/− rats to typical SCFAs, we evaluated the relaxation of phenylephrine-contracted mesenteric arteries when exposed to a submaximal dose (5 mM) of acetate, propionate or butyrate. As shown in Figure 6B, the 3 SCFAs caused an initial rapid, transient additional contraction and was followed by a sustained, slower relaxation phase that lasted for about 10 minutes. The time-to-plateau of the acetate induced relaxation was significantly slower in Gper1−/− compared to control vessels. In addition, the average of maximum relaxation induced by acetate was decreased in Gper1−/− arteries (55±5% vs. 43±4%, n=33–36 SMAs/group, p=0.01). The time-to-plateau for butyrate induced relaxation was indistinguishable between Gper1−/− and control vessels, but the average maximum relaxation was significantly decreased (61±5% vs. 47±4%, n=34–36 SMAs/group, p<0.001). Propionate induced relaxation was similar between the two groups (64±4% vs. 61±4%, n=34–36 SMAs/group, p=0.98).

Discussion

Over recent years, evidence has accumulated in support of a role of Gper1 in the regulation of vascular reactivity and BP. However, data on the role of Gper1 in cardiovascular disease is conflicting with pharmacological interventions and gene deletion models reporting both a protective and permissive nature of Gper1 on hypertension in particular9,19. We present a novel CRISPR/Cas9 edited deletion rat model of Gper1 using the Dahl Salt-Sensitive rat strain, a model of salt-sensitive hypertension, which provides a unique opportunity to examine the functionality of Gper1 in the context of hypertension. Three major findings ensued as a result. First, Gper1−/− rats had significantly altered gut microbiota compared to the Gper1+/+ rats. The microbiota alterations included a reduced Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes ratio, indicating that ablation of a single gene, Gper1, improved the dysbiosis evident in the Gper1+/+ rats. Second, this reduced dysbiosis was associated with a significant reduction in both SBP and DBP compared to Gper1+/+ rats in both males and females, which was accompanied by improvement in vascular function. Third, changing the composition of the gut microbiota of Gper1−/− rats to that of Gper1+/+ animals by cecal transplantation worsened BP in Gper1−/− rats, indicating that the improved BP was due to the altered microbiota.

The prominent BP lowering effect that resulted from genetic deletion of Gper1 in the S rat is not the same as previous studies in mouse and rat, in which activation of Gper1 promotes vasorelaxation and a lowering of BP 9,18,26–28. However, the microbiota of these models were not characterized in these studies. The model that was used here, the S rat, not only has a highly permissive genomic background for the development of hypertension, but also has a well-studied microbiome20. Besides providing a potential explanation to the apparently discrepant results, this also highlights the strong influence of the microbiome on functionality of a particular gene in BP regulation. Moreover, we recently showed that in this Dahl S model the composition of the gut microbiota strongly influences BP regulation 20. With this precedent, we sought to determine whether the deletion of Gper1 rats was accompanied by differences in gut microbiota composition. This notion was reinforced by the unexpected results of the microbiota analysis of fecal samples from Gper1−/− and Gper1+/+ rats, which revealed marked differences in bacterial species richness between the two groups of animals, as shown by PCoA plots and the taxonomic data. In particular, before the microbiotal transplant, Gper1−/− rats exhibited significantly reduced levels of Clostridiales under the phylum Firmicutes in comparison to the wild-type Gper1+/+ animals, and had a marked decrease in the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio. This is interesting, as a recent study showed an increased ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes in spontaneously hypertensive rats (hypertensive strain) as compared to Wistar Kyoto rats (normotensive strain) 29. Similar changes in gut microbiota composition were found in the chronic angiotensin II infusion rat model and in a small cohort of hypertensive patients 29. Other studies confirmed that this ratio is significantly correlated with BP30–33. Moreover, because of the similar genetic background between Gper1−/− and wild-type Gper1+/+ rats, the different composition of the gut microbiota between these strains suggests that Gper1 alters host symbiotic relationships with the gut microbial communities. One potential drawback of our study is that while the body weights and nasal-anal lengths of these rats were different, we did not measure the food, salt or fluid intake, whereby it remains unknown whether these factors or the change in body weight contributed to the results. Therefore, it is possible that the altered body weight and food intake altered the microbiome independent of the genetic differences.

The ability of one gene to alter microbiota is not new, but has been documented previously in mice with the Toll-like receptor 5 gene34. Toll-like receptor 5 knockout (Tlr5−/−) mice have significantly altered gut microbiota compared to control mice34. The altered microbiota had an increased Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio, and the mice had associated metabolic disease and elevated BP34.

In order to determine if the changes in microbiota are causative for the BP lowering effects observed, we transplanted cecal content from wild-type Gper1+/+ rats. Our findings demonstrate that after colonization of the gut microbiota from wild-type Gper1+/+ rats, the BP lowering effect of Gper1−/− was abolished in both genders and the BP was even slightly increased in female rats. This suggests that gut microbiota play a significant role in Gper1-dependent regulation of BP in hypertensive rats. Another experimental design to test the BP effect of microbiota from Gper1−/− rats would be to transplant both Gper1+/+ rats and Gper1−/− rats with microbiota from Gper1−/− rats, which has admittedly not been conducted in our study. This raises the question of whether a transplant from Gper1−/− rats to Gper1−/− rats may cause strain-specific effects on BP that are different from the Gper1+/+ rat to Gper1+/+ rat transfer. However, based on previous studies 20, wherein we did not observe any strain dependent effects on BP, such differences, albeit unlikely, remains to be tested. Therefore, it could be possible that the BP effects we are seeing in the Gper1−/− rats in this experiment are due to the experiment itself and not the microbiotal transfer.

In vivo, circulating SCFAs are among the best characterized end products of gut microbial fermentation, which have been linked to the regulation of BP in the host 35–37. Among these, acetate, propionate and butyrate are microbiota-derived SCFAs produced in the cecum and large intestine from where they are transported into portal circulation where they exert a vasorelaxant effect 38,39. Our data show that mesenteric arteries from Gper1−/− rats have an impaired vasorelaxation response to maximal concentrations of acetate and butyrate compared to wild-type Gper1+/+ rats. Several studies indicate that the vascular actions of SCFAs are mediated by G protein coupled receptors (GPRs) including Gpr41, Gpr43, Gpr109a and Olfr78 1,2,40–42. Our findings showing impaired vascular response to typical SCFAs in vessels from Gper1−/− rats reveal a previously unrecognized function of Gper1 as a modulator of the biological actions of SCFAs. Additional studies are needed to determine whether this results from a direct effect of SCFAs on Gper1 or subsequent signaling crosstalk between Gper1 and SCFAs receptors of the GPR family. While a response of Gper1 to SCFAs was identified in this study, the vasodilatory response was small compared to what would be expected with the large BP changes noted. Therefore, while these results show a possible link between Gper1, gut microbiota, and BP control, the exact mechanism by which deletion of Gper1 improves BP is still unknown. Additionally, the direct mechanism by which the deletion of Gper1 significantly alters the microbiome needs further investigation. While there are reports in the literature of GPRs interacting with microbiota40,43,44, the relationship between them is very complex and difficult to study. Perhaps one of the complications of studying this GPR-microbiotal relationship is that there are multiple GPRs that have both similar and opposing effects. All of these receptors together exert physiological effects. Therefore, trying to determine the interactions between just one of them and the microbiota is expected to be difficult. Considering this difficulty, our finding that deletion of Gper1 caused alterations in microbiotal composition is significant and suggests that the other GPRs were perhaps unable to compensate for the effects of the deletion of Gper1. This makes Gper1 an interesting target for microbiotal-dependent cardiovascular effects.

Gper1 maps on to chromosome 7p22, a region implicated in hypertension in humans 7,45, and a recent survey in normal healthy adults has shown that impaired Gper1 function might be associated with increased BP and risk of hypertension 46. Interestingly, a common genetic variant of GPER1, Gper1P16L, was found to be hypofunctional and associated with increased BP in females 46. It will be interesting to study, whether, like in the rat models, microbiotal compositions are linked to the host allelic variants of human GPER1. Additionally, contemplation of Gper1 as a target for therapeutic intervention in the management of cardiovascular disease may require caution due to the contextual dependency of the function of Gper1 on the host genome and the associated microbiome.

Perspectives

In this study, we sought to study the BP regulatory role of Gper1 in the Dahl Salt-Sensitive rat model of hypertension. Compared with their wild-type littermates, Gper1−/− rats showed significantly lower BP effect, which was abolished when the gut microbiota of the Gper1−/− rats was swapped with that of wild-type rats. In addition, using ex vivo model we demonstrated impaired vasorelaxation in Gper1−/− rats mesenteric arteries in response to SCFAs, which are major metabolites of gut microbiota. This data provide important evidence to suggest a role of microbiota in the BP regulation by Gper1. Given the growing evidence for host-microbiotal interactions in health and disease, our data support Gper1 as one of the host genomic factors responsible for cross-talk with microbiota to regulate cardiovascular physiology and prompts investigation into further precise mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significances.

What Is New?

Genetic deletion of a single gene, Gper1, in Dahl-salt sensitive S rats, caused alterations in gut microbiotal composition and blood pressure in these rats.

Restoring the gut microbiota of the Gper1−/− rats with that of wild-type rats by cecal transplantation, resulted in further elevated BP in these rats confirming a microbiotal-dependent mechanism for regulation of BP by Gper1.

Altered vascular responses of SCFAs in the small mesenteric arteries of Gper1−/− rats as compared to wild-type rats prompts further studies to be focused on this microbiotal-dependent regulation of BP by Gper1 to have functional implications in the vasculature.

What Is Relevant?

Host-microbiotal interactions are increasingly being recognized for their important effects on health and disease. Our study adds to this literature by demonstrating that a single host genomic site can have a powerful impact as a determinant of microbiotal composition and related cardiovascular health as demonstrated in a rat model of hypertension.

G-protein coupled receptors are a well characterized class of receptors which are involved in many disorders including hypertension. Here we report a lesser studied G-protein coupled receptor, Gper1, as a modulator of BP via a microbiotal dependent mechanism.

Our study is also the first to report the approach of a modified CRISPR/Cas9 approach of multiplexing gRNAs to completely delete a rat locus.

Summary.

This study tested a modified CRISPR/Cas9 genome-engineering approach in the rat model with assessment of the function of a lesser studied G-protein coupled receptor, Gper1, in cardiovascular physiology. The results of our study can be viewed from two different perspectives as follows: From the genome-engineering perspective, our study is the first to demonstrate the application and ease with which dual gRNAs can be used to completely excise individual genes. From the physiological perspective, our data reveal that Gper1 regulates BP via a microbiotal-dependent mechanism.

Acknowledgments

BJ acknowledges support from the University of Toledo and funding from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (HL020176).

Sources of Funding: The work was supported by the National Institute of Health, grant numbers HL020176 and HL112641 to Dr. Bina Joe.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Pluznick JL. Extra sensory perception: the role of Gpr receptors in the kidney. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23(5):507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Poul E, Loison C, Struyf S, et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278(28):25481–25489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodhankar S, Offner H. Gpr30 Forms an Integral Part of E2-Protective Pathway in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Immunol Endocr Metab Agents Med Chem. 2011;11(4):262–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takada Y, Kato C, Kondo S, Korenaga R, Ando J. Cloning of cDNAs encoding G protein-coupled receptor expressed in human endothelial cells exposed to fluid shear stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240(3):737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerman MA, Budish RA, Kashyap S, Lindsey SH. GPER-novel membrane oestrogen receptor. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016;130(12):1005–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gencel VB, Benjamin MM, Bahou SN, Khalil RA. Vascular effects of phytoestrogens and alternative menopausal hormone therapy in cardiovascular disease. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry. 2012;12(2):149–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas E, Bhattacharya I, Brailoiu E, et al. Regulatory role of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor for vascular function and obesity. Circ Res. 2009;104(3):288–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jessup JA, Lindsey SH, Wang H, Chappell MC, Groban L. Attenuation of salt-induced cardiac remodeling and diastolic dysfunction by the GPER agonist G-1 in female mRen2.Lewis rats. PloS one. 2010;5(11):e15433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martensson UE, Salehi SA, Windahl S, et al. Deletion of the G protein-coupled receptor 30 impairs glucose tolerance, reduces bone growth, increases blood pressure, and eliminates estradiol-stimulated insulin release in female mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150(2):687–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gros R, Ding Q, Liu B, Chorazyczewski J, Feldman RD. Aldosterone mediates its rapid effects in vascular endothelial cells through GPER activation. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 2013;304(6):C532–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gros R, Ding Q, Sklar LA, et al. GPR30 expression is required for the mineralocorticoid receptor-independent rapid vascular effects of aldosterone. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):442–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briet M, Schiffrin EL. Vascular actions of aldosterone. Journal of vascular research. 2013;50(2):89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam HM, Ouyang B, Chen J, et al. Targeting GPR30 with G-1: a new therapeutic target for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2014;21(6):903–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wegner MS, Wanger RA, Oertel S, et al. Ceramide synthases CerS4 and CerS5 are upregulated by 17beta-estradiol and GPER1 via AP-1 in human breast cancer cells. Biochemical pharmacology. 2014;92(4):577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacenik D, Cygankiewicz AI, Krajewska WM. The G protein-coupled estrogen receptor as a modulator of neoplastic transformation. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2016;429:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srivastava DP, Evans PD. G-protein oestrogen receptor 1: trials and tribulations of a membrane oestrogen receptor. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2013;25(11):1219–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm A, Hellstrand P, Olde B, Svensson D, Leeb-Lundberg LM, Nilsson BO. The G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1/GPR30) agonist G-1 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell Ca(2)(+) handling. Journal of vascular research. 2013;50(5):421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, Kashyap S, Murphy B, et al. GPER activation ameliorates aortic remodeling induced by salt-sensitive hypertension. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 2016;310(8):H953–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer MR, Fredette NC, Daniel C, et al. Obligatory role for GPER in cardiovascular aging and disease. Science signaling. 2016;9(452):ra105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mell B, Jala VR, Mathew AV, et al. Evidence for a link between gut microbiota and hypertension in the Dahl rat. Physiological genomics. 2015;47(6):187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh V, Chassaing B, Zhang L, et al. Microbiota-Dependent Hepatic Lipogenesis Mediated by Stearoyl CoA Desaturase 1 (SCD1) Promotes Metabolic Syndrome in TLR5-Deficient Mice. Cell metabolism. 2015;22(6):983–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng X, Qiu Y, Zhong W, et al. A targeted metabolomic protocol for short-chain fatty acids and branched-chain amino acids. Metabolomics. 2013;9(4):818–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saad Y, Garrett MR, Manickavasagam E, et al. Fine-mapping and comprehensive transcript analysis reveals nonsynonymous variants within a novel 1.17 Mb blood pressure QTL region on rat chromosome 10. Genomics. 2007;89(3):343–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature methods. 2010;7(5):335–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manichanh C, Reeder J, Gibert P, et al. Reshaping the gut microbiome with bacterial transplantation and antibiotic intake. Genome Res. 2010;20(10):1411–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li ZL, Liu JC, Liu SB, Li XQ, Yi DH, Zhao MG. Improvement of vascular function by acute and chronic treatment with the GPR30 agonist G1 in experimental diabetes mellitus. PloS one. 2012;7(6):e38787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsey SH, da Silva AS, Silva MS, Chappell MC. Reduced vasorelaxation to estradiol and G-1 in aged female and adult male rats is associated with GPR30 downregulation. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism 2013;305(1):E113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindsey SH, Chappell MC. Evidence that the G protein-coupled membrane receptor GPR30 contributes to the cardiovascular actions of estrogen. Gend Med. 2011;8(6):343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, et al. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;65(6):1331–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu P, Li M, Zhang J, Zhang T. Correlation of intestinal microbiota with overweight and obesity in Kazakh school children. BMC microbiology. 2012;12:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marques FZ, Nelson E, Chu PY, et al. High-Fiber Diet and Acetate Supplementation Change the Gut Microbiota and Prevent the Development of Hypertension and Heart Failure in Hypertensive Mice. Circulation. 2017;135(10):964–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wanyonyi S, du Preez R, Brown L, Paul NA, Panchal SK. Kappaphycus alvarezii as a Food Supplement Prevents Diet-Induced Metabolic Syndrome in Rats. Nutrients. 2017;9(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jose PA, Raj D. Gut microbiota in hypertension. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. 2015;24(5):403–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, et al. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science. 2010;328(5975):228–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyamoto J, Kasubuchi M, Nakajima A, Irie J, Itoh H, Kimura I. The role of short-chain fatty acid on blood pressure regulation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2016;25(5):379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natarajan N, Hori D, Flavahan S, et al. Microbial short chain fatty acid metabolites lower blood pressure via endothelial G-protein coupled receptor 41. Physiological genomics. 2016:physiolgenomics 00089 02016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natarajan N, Pluznick JL. From microbe to man: the role of microbial short chain fatty acid metabolites in host cell biology. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307(11):C979–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knock G, Psaroudakis D, Abbot S, Aaronson PI. Propionate-induced relaxation in rat mesenteric arteries: a role for endothelium-derived hyperpolarising factor. J Physiol. 2002;538(Pt 3):879–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mortensen FV, Nielsen H, Aalkjaer C, Mulvany MJ, Hessov I. Short chain fatty acids relax isolated resistance arteries from the human ileum by a mechanism dependent on anion-exchange. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;75(3–4):181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pluznick JL, Protzko RJ, Gevorgyan H, et al. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(11):4410–4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pluznick J A novel SCFA receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(2):202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pluznick JL. Renal and cardiovascular sensory receptors and blood pressure regulation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(4):F439–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pluznick J A novel SCFA receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(2):202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Natarajan N, Hori D, Flavahan S, et al. Microbial short chain fatty acid metabolites lower blood pressure via endothelial G-protein coupled receptor 41. Physiological genomics. 2016;48(11):826–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lafferty AR, Torpy DJ, Stowasser M, et al. A novel genetic locus for low renin hypertension: familial hyperaldosteronism type II maps to chromosome 7 (7p22). Journal of medical genetics. 2000;37(11):831–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feldman RD, Gros R, Ding Q, et al. A common hypofunctional genetic variant of GPER is associated with increased blood pressure in women. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.