Abstract

Background

The human p.G2434R variant of the RYR1 gene is most frequently associated with malignant hyperthermia (MH) in the UK. We report the phenotype of a knock-in mouse that expresses the RYR1 variant p.G2435R, which is isogenetic with the human variant.

Methods

We observed the general phenotype; determined the sensitivity of myotubes to caffeine-, KCl—, and halothane-induced Ca2+ release; determined the in vivo response to halothane or increased ambient temperature; and determined the in vivo myoplasmic intracellular Ca2+ concentration in skeletal muscle before and during exposure to volatile anaesthetics.

Results

RYR1 pG2435R/MH normal (MHS-Heterozygous[Het]) or RYR1 pG2435R/pG2435R (MHS-Homozygous[Hom]) mice were fully viable under typical rearing conditions, although some male MHS-Hom mice died spontaneously. The normalised half-maximal effective concentration (95% confidence interval) for intracellular Ca2+ release in myotubes in response to KCl [MH normal, MHN, 21.4 (19.8–23.1) mM; MHS-Het 16.2 (15.2–17.2) mM; MHS-Hom 11.2 (10.2–12.2) mM] and caffeine (MHN, 5.7 (5–6.3) mM; MHS-Het 4.5 (3.9–5.0) mM; MHS-Hom 1.77 (1.5–2.1) mM] exhibited a gene dose-dependent decrease, and there was a gene dose-dependent increase in halothane sensitivity. Intact animals show a gene dose-dependent susceptibility to MH with volatile anaesthetics or to heat stroke. RYR1 p.G2435R mice had elevated skeletal muscle intracellular resting [Ca2+]i, (values are expressed as mean (SD)) (MHN 123 (3) nM; MHS-Het 156 (16) nM; MHS-Hom 265 (32) nM; P<0.001) and [Na+]i (MHN 8 (0.1) mM; MHS-Het 10 (1) mM; MHS-Hom 14 (0.7) mM; P<0.001) that was further increased by exposure to volatile anaesthetics.

Conclusions

RYR1 pG2435R mice demonstrated gene dose-dependent in vitro and in vivo responses to pharmacological and environmental stressors that parallel those seen in patients with the human RYR1 variant p.G2434R.

Keywords: gene knock-in techniques, malignant hyperthermia, mouse, ryanodine receptor 1

Editor's key points.

-

•

The molecular mechanisms by which RYR1 variants confer MH susceptibility are unknown.

-

•

RYR1 pG2435R knock-in mice, a mouse model of the most common human variant, were created and characterised phenotypically and biochemically.

-

•

This novel mouse model recapitulates in vitro and in vivo responses to pharmacological and environmental stressors compared with the common human RYR1 variant p.G2434R.

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a hypermetabolic condition triggered in genetically predisposed individuals by any of the potent volatile anaesthetics and by succinylcholine.1 The MH crisis is characterised by hypermetabolism, hypercapnia, tachycardia, hypoxaemia, muscle rigidity, respiratory and metabolic acidosis, and hyperthermia. The great majority of MH-susceptible patients remains subclinical until challenged with pharmacological triggering agents.1, 2, 3, 4 If left untreated, the mortality of a fulminant MH episode is >70%, but improved understanding, better monitoring, and availability of dantrolene have reduced mortality to <8%.1, 5 The prevalence of MH susceptibility based on clinical incidence is estimated to range from as low as 1 in 250 000 to as high as 1 in 200, depending on the age and geographic location of the population, although accurate measures of MH susceptibility prevalence as a genetic predisposition remains difficult because of variable penetrance and the poor epidemiological data.6, 7, 8 MH susceptibility can be diagnosed in patients with high a priori risk using the in vitro contracture test (IVCT) that measures contractile responses to halothane or caffeine of vastus lateralis or vastus medialis muscle biopsies.6, 9

Molecular genetic studies have established the type 1 ryanodine receptor gene (RYR1) encoding the skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release channel (RyR1 protein) as the primary locus for both MH susceptibility and central core disease (CCD).4, 6, 7, 10 More than 200 RYR1 variants have been associated with MH, CCD, or both.7 Although MH-related RYR1 variants can be found in all regions of the gene, most have been described in three clusters corresponding to the: N-terminal (C35-R614, MH region 1), central (D2129-R2458, MH region 2), and C-terminal (I3916-A4942, MH region 3) regions of the RyR1 protein. To date, a porcine and three knock-in murine models that express RYR1 variants analogous to variants associated with human MH have been described. Two murine, p.R163C11 and p.Y522S,12 and the porcine p.R615C13, 14, 15 models have mutations in MH region 1 of the N-terminal domain of RyR1. The third currently available murine mutant RyR1 MH model, p.T4826I,16 involves MH region 3 in the putative cytoplasmic linker between transmembrane segments S4 and S5.17 All four models reported exhibit anaesthetic-triggered fulminant MH episodes and environmental heat stress, with varying gene–dose relationships. The molecular mechanisms by which RYR1 variants confer MH susceptibility are unknown. A common characteristic of all animal models with MH-RyR1 mutations to date is an increased resting skeletal muscle intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i)14, 18, 19 compared with non-susceptible muscle. In porcine and murine models, we have shown that exposure to halothane or isoflurane at clinically relevant concentrations causes [Ca2+]i to rise several fold in MH susceptible (MHS) muscle, whereas exposure to the same concentrations of halothane or isoflurane has no effect in non-susceptible (MHN) muscle.15, 19, 20

Although interesting observations have been made using these models involving MH regions 1 and 3, the most prevalent RYR1 variant associated with human MH is NM_000540.2(RYR1_i001):p.(Gly2434Arg (G2434R)), which is caused by a missense point mutation NM_000540.2:c.7300G>A in exon 44 involving MH region 2 of the RyR1 protein.21 Because of its prevalence, the p.G2434R variant has been used as the comparator variant for describing differences in human phenotypes associated with different RYR1 genotypes.22 For example, MHS patients with the p.G2434R variant have a relatively weak IVCT phenotype and are less likely to have an elevated serum creatine kinase concentration compared with humans with either the p.T4826I or p.R163C RyR1 variants.22 Furthermore, p.G2434R is not associated with CCD and is the most frequent variant associated with MH in the UK to be implicated in familial genotype–phenotype discordance.7, 21 The genotype–phenotype discordance is present in almost 22% of families in which segregation analysis has been done, and includes individuals who are carriers of the p.G2434R variant but have a normal IVCT and individuals who do not carry the familial p.G2434R variant but have an abnormal IVCT.21

Detailed study of the p.G2434R variant is crucial to identify fundamental molecular mechanisms that are generically implicated in MH. Furthermore, a model of p.G2434R is necessary if we are to have confidence that human RYR1 genotype–phenotype relationships are recapitulated in isogenic murine models. The aim of the present study was to develop a new knock-in murine model of MH with a mutation in RyR1 MH region 2 (p.G2435R), and to characterise whole animal and cellular phenotypes of heterozygous and homozygous mice.

Methods

Animal care and maintenance

All experiments on animals from the creation of knock-in mice to establishment of their physiological and biochemical phenotypes were conducted using protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committees (IACUCs) at Harvard Medical School, University of California at Davis, MRC Harwell, and University of Leeds; the latter two both through project licenses approved by the UK Home office. Animals were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions with free access to food and water and a 12 h light and dark cycle.

Creation of p.G2435R knock-in MH mice

Site-directed mutagenesis (QuickChange Multi-Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to mutate the glycine at codon 2435 in the murine RyR1 to arginine (p.G2435R). This mutation is equivalent to amino acid position 2434 in human RyR1. A 5.862 kb NotI fragment harbouring RYR1 exons 40–47 (Supplementary Fig. S1A) was isolated from a 129Sv/J mouse genomic library and used to construct the targeting vector. A bacterial locus of crossover in P1 (LoxP) recombination site flanked neomycin (G418) cassette was inserted between the 3.9 kb upstream arm and the 1.9 kb downstream arm. 129Sv embryonic stem cells were electroporated with the linearised vector and subjected to positive selection with G418 using standard techniques as described.11, 16 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was used to identify homologous recombination at this location (Supplementary Fig. S1B and C), and the presence of the mutation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. A clone identified as carrying the p.G2435R mutation was injected into C57BL/6 murine blastocysts and implanted into pseudopregnant mice. Male chimeric mice were mated with female C57BL/6 mice, and germ line transmission was confirmed by the presence of agouti coat colour and PCR screening. These mice were then bred to Tnap-Cre (tissue-non-specific alkaline phosphatase promoter-driven Cre recombinase) transgenic mice11, 16 to excise the LoxP-flanked neo cassette. The resulting progeny with the neomycin cassette excised, which were used in the present study, were backcrossed for two rounds with C57BL/6 wild type (MHN) mice and then crossbred to produce mice carrying either one (HET) or two (HOM) alleles with the mutation and maintained as either Hom (male) × Hom (female) or Het (male) × Hom (female) crosses.

Experimental preparations

The following experiments were conducted:

-

(i)

In vitro using myoblasts from C57BL/6 (MHN), heterozygous MHS-p.G2435R (MHS-Het), and homozygous MHS-p.G2435R (MHS-Hom) mice. Myoblasts were obtained via enzymatic digestion of excised rear and foreleg skeletal muscles and isolated as a pure myoblast culture.23 For measurements of Ca2+ transients, myoblasts were expanded to >60% confluence in growth media and differentiated into myotubes by culturing for 4–6 days in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 2% heat inactivated horse serum and no added growth factors in Greiner μCLEAR® 96-well plates18 (Greiner Bio One, Stonehouse, UK).

(ii) In vivo, (a) in intact awake mice exposed to increased environmental temperature or halothane and (b) using Ca2+-selective electrodes to measure [Ca2+]i in vastus lateralis fibres of anaesthetised (ketamine 100 mg kg−1 and xylazine 2 mg kg−1) MHN, MHS-Het, and MHS-Hom mice that were exposed, cleaned of fascia and adipose tissue, and then impaled with the electrodes as described.19

Measurements of Ca2+ transients in MHN, MHS-Het, and MHS-Hom skeletal myotubes during exposure to caffeine, KCl, and halothane

Differentiated myotubes were loaded with 5 μM Fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR, USA) at 37°C, for 15 min in imaging buffer. Cells were then washed three times with imaging buffer and transferred to a fluorescence microscope. Fluo-4 was excited at 494 nm and its emission measured at 516 nm using a 40× 1.3 NA oil objective. Images were collected with an intensified 12-bit digital intensified charge-coupled device (ORCA-ER, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan), and analysed from regions of interest in individual cells using Image J software (NHLBI) and Prism 7 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Using a multivalve perfusion system (Automate Scientific Inc., Oakland, CA, USA), a concentration–response curve for each agent was performed to compare the response to any given agent among primary myotubes from MHN, MHS-Het, or MHS-Hom mice. The average fluorescence of the Ca2+ transient (defined by the area under the transient curve) was measured and compared among genotypes. Individual areas under the curve were calculated as the average fluorescence during the challenge minus the average baseline fluorescence for 1 s immediately before the challenge. Because of variability in responses from cell to cell, individual response amplitudes for caffeine and KCl were normalised to the maximum response obtained by that cell to the highest concentration of the reagent being tested (20 mM caffeine, 60 mM KCl), and halothane responses were normalised to the maximum response of that cell to 60 mM KCl. For caffeine and KCl experiments, data were obtained from 42 to 53 differentiated myotubes per genotype (from 12 to 15 different wells in three to four plates cultured on different days). For KCl experiments data were obtained from 30 to 37 differentiated myotubes per genotype (from five to six different wells in four to five plates cultured on different days). For halothane experiments, data were obtained from 33 to 46 differentiated myotubes (from five to six different wells in three to six plates cultured on different days). Halothane concentrations were confirmed with gas chromatography.24

Basal core temperature and responses to heat stress in vivo

Basal rectal (core) temperature was measured in equal numbers of male and female awake mice in all three genotypes using a thermistor probe when they were first removed from their home cage (environmental range 24–26°C) and recorded digitally (TC-324B Automatic Temperature Controller extension; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) after the reading stabilised (30 s). To investigate heat stress responses, mice were gently restrained and transferred to a 38°C test chamber (MHN, n=9, 8–18 months; MHS-Het, n=14, 10–16 months; MHS-Hom, n=14, 4–13 months). Rectal temperature was measured continuously during the heat stress challenge (up to 80 min) or until the time of fulminant heat stroke, whichever came first. All MHN animals survived the exposure to increased ambient temperature and were euthanised at this time; however, all MHS animals expired as a result of heat stroke with limb and tail rigidity within the experimental time.

Basal core temperature and responses to halothane exposure in vivo

Mice were weighed, had their baseline temperature recorded, and then placed into an anaesthetic chamber. Anaesthesia was induced with 2.0 vol% halothane in oxygen using a precision vaporiser (Ohmeda Tec-4 halothane vaporiser system; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) with flows at 1.5 L min−1 until there was no detectable response to toe pinches (30–60 s). Next, mice were rapidly placed atop a bed warmed to achieve a bed surface temperature of 37°C. Anaesthesia was maintained with halothane, 1.5 vol% in oxygen via a nose-cone attachment and a rectal thermistor inserted. Animals were continuously monitored for fluctuations in body temperature and signs of fulminant MH (limb and tail rigidity). Data were recorded every 2 min for the first 10 min, and then every 5 min for up to 70 min or until the animal died of an MH crisis. The onset of fulminant MH was determined by close surveillance for increased body temperature, hyperacute rigor in extremities (limb flex response), and cessation of breathing. All MHN animals survived the halothane challenge and were then euthanised under anaesthesia. All MHS animals expired as a result of an MH episode within the experimental time.

Ca2+ and Na+ selective microelectrodes

Double-barrelled Ca2+- and Na+-selective microelectrodes were prepared as described.25, 26 Each ion-selective microelectrode was individually calibrated before and after in vivo determinations.26 Only Ca2+-selective microelectrodes with a linear relationship between pCa 3 and 7 (Nernstian response, 29.5 and 30.5 mV per pCa unit at 23°C and 37°C, respectively) were used. The Na+-selective microelectrodes gave virtually Nernstian responses at free [Na+]e between 100 and 10 mM. However, at concentrations between 10 and 1 mM [Na+]e, the electrodes had a sub-Nernstian response (40–45 mV), but their overall response was of a sufficient amplitude to be able to measure [Na+]i in all genotypes. The sensitivity of the Ca2+- and Na+-selective microelectrodes was not affected by any of the reagents used in the study.

In vivo intracellular Ca2+ and Na+ determinations in muscle fibres

MHN and MHS mice were anaesthetised with ketamine and xylazine, and both vastus lateralis muscles were exposed and trimmed of fascia and fat. The exposed myofibres on the right side were impaled with a double-barrelled Ca2+-selective microelectrode and on the left side with a double-barrelled Na+-selective microelectrode, and their potentials were recorded using a high-impedance amplifier (WPI Duo 773 electrometer; WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA). The potentials from the 3 M KCl microelectrode (Vm) were subtracted electronically from the potential of the ion selective electrode (VCaE or VNaE) to produce a differential Ca2+-specific potential (VCa) or Na+-specific potential (VNa) that represents free [Ca2+]i or [Na+]i, respectively. Vm, VCa, and VNa were filtered (30–50 kHz) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and stored in a computer for further analysis.

An initial set of measurements before exposure was made to obtain the baseline and then animals were exposed to either 2 vol% halothane or 1.5 vol% isoflurane delivered by facemask from a calibrated metered vaporiser. Measurements of [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i were made 2–4 min after commencing exposure to the anaesthetic.

Solutions

For in vitro studies, stock solutions of caffeine, KCl, and halothane were prepared in imaging buffer with the following composition: 133 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5.5 mM glucose, and 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.4. In KCl containing solutions, the concentration of NaCl was adjusted to maintain a total cation concentration (K+ + Na+) of 138 mM. For in vivo studies, Ringer's solution [with the following composition (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4] was used to keep exposed muscle hydrated.

Statistics

Values for myotube experiments are expressed as mean (95% confidence interval, CI) with n denoting the number of myotubes for each condition. Values for mice and adult fibres are expressed as mean (standard deviation, sd), with nmice representing the number of mice and ncell representing the number of myofibres used for the in vivo experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (anova) and Tukey's t-test for multiple comparisons to determine significance, which was accepted for P<0.05.

Results

RyR1 pG2435R mouse phenotype and survival

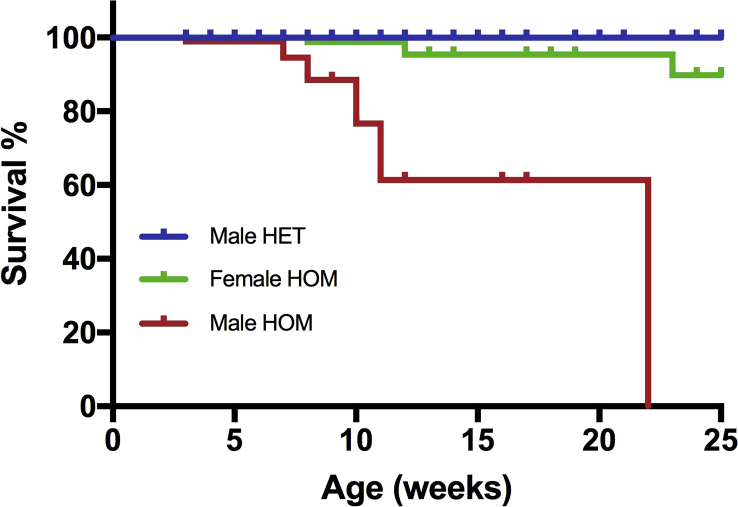

MHS-Het mice and MHS-Hom mice had no apparent abnormalities and appeared healthy at birth. Although initially Hom mice had no issues and could be maintained and the colony expanded as Hom × Hom mating trios, in the ∼F6 generation it became evident that the MHS-Hom males did not make good breeding partners and were frequently found dead in their cage at ages 3–8 weeks. At the same time, it was noticed that some MHS-Hom males housed with littermate MHS-Het or MHN males died within 8 weeks and if housed only with MHS-Hom littermates they survived up to 22 weeks before spontaneous death, which was of no apparent outside cause. Only three MHS-Hom females died spontaneously with 18 months being the longest time for any animal to be kept before being used for an experiment. Although we had not planned an a priori survival analysis, post hoc Kaplan–Meier analyses (Supplementary Fig. S2) revealed a significant difference between survival curves for male and female MHS-Hom mice and all other genotypes (P<0.0001, log-rank test). The hazard ratio (log-rank) for male vs female MHS-Hom mice was 8.3 (95% CI, 3.2–21.6).

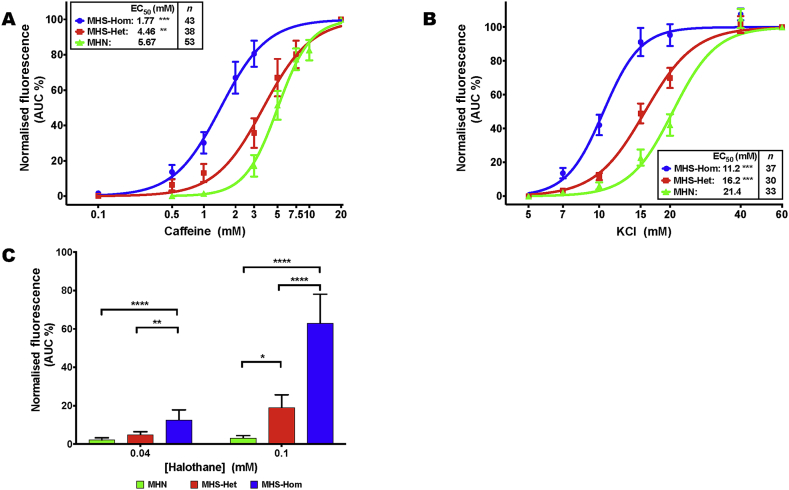

In vitro myotube Ca2+ responses to caffeine, KCl, and halothane

There were significant differences in both the threshold and the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of the intracellular Ca2+ response to increasing concentrations of caffeine and KCl, and increased sensitivity to halothane among MHN, MHS-Het, and MHS-Hom myotubes (Fig. 1A–C). The EC50 values for caffeine were 5.7 (95% CI 5.0–6.3), 4.5 (3.9–5.0), and 1.8 (1.5–2.1) mM (Fig. 1A) and for KCl were 21 (20–23), 16 (15–17), and 11 (10–12) mM (Fig. 1B) for MHN, MHS-Het, and MHS-Hom, respectively. MHS-Homs had a significant response to 0.04 mM halothane of 12.7% maximum KCl response (7.6–17.9), and both MHS-Homs and MHS-Hets had a response to 0.1 mM halothane that was significantly greater than that of MHN mice [19.1% (12.4–25.7) and 63.1% (48.1–78.1) of maximum KCl response for MHS-Het and MHS-Hom, respectively], whereas MHN myotubes had no significant response to halothane at either of these concentrations: 2.3% maximum KCl response (1.2–3.3) and 3.2% (2.0–4.4) for 0.04 and 0.1 mM halothane, respectively (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1.

Sigmoidal concentration–response analysis of Ca2+ imaging in myotubes generated from MHN, MHS-Het, and MHN-Hom p.G2435R mice in response to (A) caffeine and (B) KCl. EC50 values are shown inset together with the number of myotubes. *EC50 values are significantly different between each genotype (P<0.001, one-way anova of log(EC50) with Tukey's multiple comparison test). The threshold response, defined as the concentration where 10% of the maximal response was observed, was 3.0, 1.0 and 0.5 mM caffeine, and 15.0, 10.0, and 7.0 mM KCl for MHN, MHS-Het, and MHS-Hom myotubes, respectively. (C) The effect of 0.04 and 0.1 mM halothane on myotubes from MHN, MHS-Het, and MHS-Hom p.G2435R mice. The halothane response has been normalised to the maximal response observed with 60 mM KCl (*P<0.05, **P<0.005, ***P<0.001 analysed using one-way anova with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, n=33–46 myotubes per genotype and dose). Data presented as mean (95% CI). anova, analysis of variance; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; EC50, half-maximal effective concentration; MH, malignant hyperthermia; MHN, MH normal; MHS-Hom, homozygous MHS; MHS-Het, heterozygous MHS.

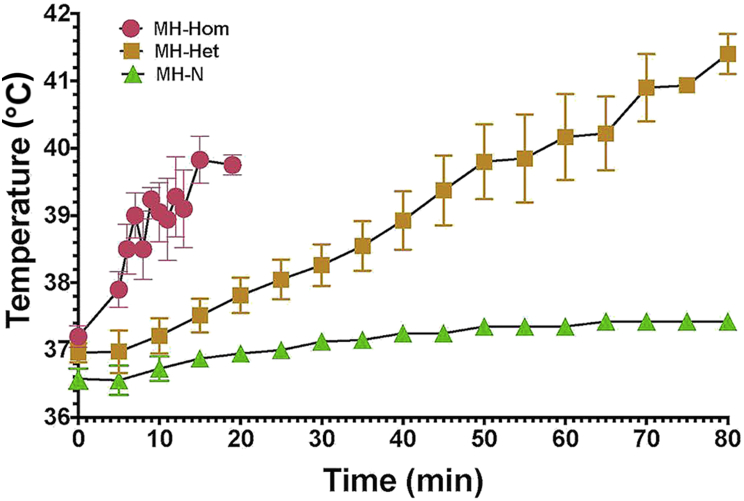

Response to 38°C ambient temperature

Exposure to increased environmental temperature triggered fulminant heat stroke resulting in death in all 10 MHS-Het and 8 MHS-Hom animals. The mean time to death for MHS-Homs was 17.9 (14.2–21.4) min and the maximum temperature reached was 39.8oC, whereas the mean time to death for MHS-Het animals was significantly longer [68.6 (62.4–73.2) min] and they died with a significantly higher mean maximum temperature of 41.8°C. There were no significant differences in either variable between males and females in either genotype. All MHN animals survived the 80 min challenge with a mean ending temperature of 37.4°C. Both sets of MHS data were significantly different than the MHN set P<0.01 (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Graph of rectal temperature vs time for eight MHS-Hom (4F, 4M), 10 MHS-Het (5F, 5M) and 10 MHN (5F, 5M) animals exposed to increased environmental temperature (38°C). Both MHS-Hom and MHS-Het animals did not survive the exposure but there was a significant difference between the time of exposure and time to death between MHS-Hom and MHS-Het. There was no significant difference between males and females in either genotype. None of the MHN animals showed a significant increase in body temperature during the 80 min exposure time and all completed the experiment unharmed. MH, malignant hyperthermia; MHN, MH normal; MHS-Hom, homozygous MHS; MHS-Het, heterozygous MHS.

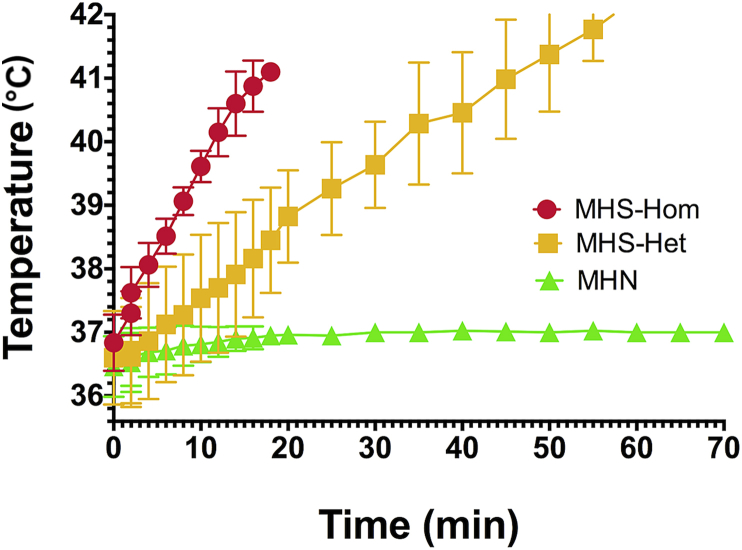

Response to exposure to halothane anaesthesia

The mean time to death for 10 MHS-Homs was 18 (15.4–20.6) min and their mean maximum temperature was 41°C. The mean time to death for 10 MHS-Het animals was significantly longer, 65.2 (58.7–69.3) min, but as with exposure to high environmental temperature they died with a significantly higher maximum temperature of 42.5°C. All MHN animals survived with a mean ending temperature at 70 min of 37°C. Both sets of MHS data were significantly different than the MHN set P<0.001 (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Graph of rectal temperature vs time for 10 MHS-Hom (5F, 5M), 10 MHS-Het (5F, 5M) and eight MHN (4F, 4M) animals exposed 2 vol% halothane. Neither MHS-Hom nor MHS-Het animals survived the exposure, but there was a significant difference between time to death and time of exposure between MHS-Hom and MHS-Het. There was no significant difference between males and females in either genotype. None of the MHN animals showed a significant increase in body temperature during the 80 min exposure time and all completed the experiment unharmed. MH, malignant hyperthermia; MHN, MH normal; MHS-Hom, homozygous MHS; MHS-Het, heterozygous MHS.

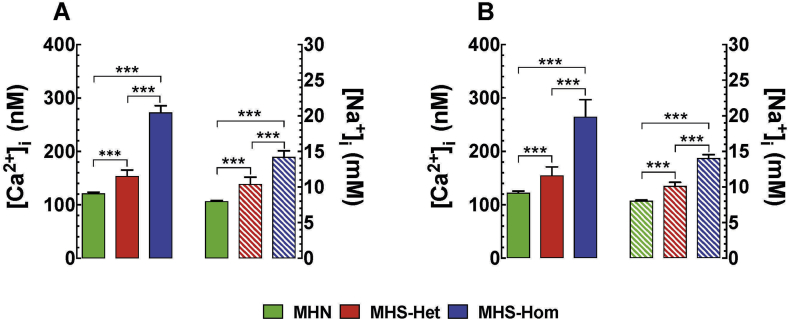

Resting [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i

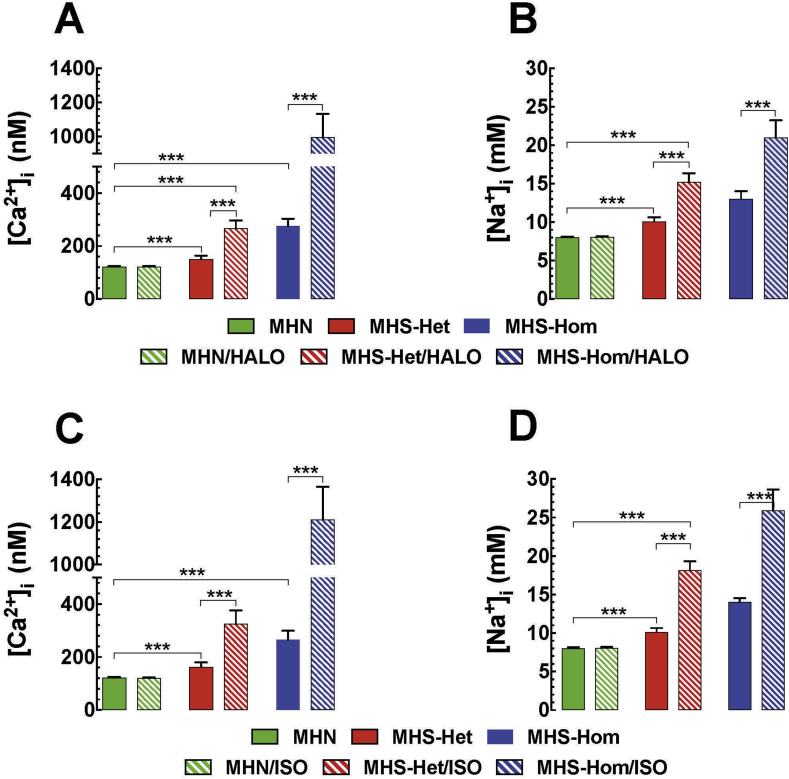

MH is characterised by intracellular Ca2+ and Na+ dyshomeostasis. Consequently, [Ca2+]i or [Na+]i was measured in vivo in quiescent fibres of the vastus lateralis from MHN and MHS mice. For MHN muscle, [Ca2+]i was 123 (120–126) nM (ncel=32, nmice=8) compared with 156 (140–172) nM (ncell=30, nmice=10) and 265 (233–297) nM (ncell=60, nmice=20) in MHS-Het and MHS-Hom fibres, respectively (Fig. 4A). [Na+]i was 8 (7.9–8.1) mM (ncell=16, nmice=4) in MHN compared with 10 (1) mM (ncell =25, nmice=5) and 14 (13.3–14.7) mM (ncell=25, nmice=5) in MHS-Het and MHS-Hom fibres, respectively (Fig. 4B). Taken together, there is intracellular Ca2+ and Na+ overload that has a gene dose effect in MHS compared with MHN muscle fibres.

Fig 4.

(A) Measurements of in vivo resting [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i in skeletal muscle and (B) similar measurement in vitro in isolated muscle fibres. In both preparations, both resting [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i were significantly different between each other and both were significantly different than control. P<0.001. [Ca2+]i, intracellular calcium; [Na+]i, intracellular sodium; MH, malignant hyperthermia; MHN, MH normal; MHS-Hom, homozygous MHS; MHS-Het, heterozygous MHS.

[Ca2+]i and [Na+]i during a malignant hyperthermia episode

We studied the effects of halothane and isoflurane on [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i in vivo in MHN and MHS mice. [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i were measured simultaneously as described above. In short, [Ca2+]i was measured in the right and [Na+]i in the left vastus lateralis muscles in MHN, MHS-Het, and MHS-Hom mice before and after exposure to 2 vol% halothane or 1.5 vol% isoflurane in the inspired gas. Halothane exposure elicited an elevation of [Ca2+]i by 1.8-fold in MHS-Het and by 3.6-fold in MHS-Hom compared with values before exposure (Fig. 5A). Also, there was an increase of [Na+]i by 1.4-fold in MHS-Het and by 1.6-fold in MHS-Hom compared with values before exposure to halothane (Fig. 5B). Isoflurane inhalation produced an elevation of [Ca2+]i by 2-fold in MHS-Het and by 4.6-fold in MHS-Hom compared with values before exposure (Fig. 5C). Isoflurane inhalation raised [Na+]i by 1.7-fold and 1.9-fold in MHS-Het and MHS-Hom, respectively, compared with values before exposure to isoflurane (Fig. 5D). There was no statistically significant difference between the effects of halothane and isoflurane on [Ca2+]i or [Na+]i. Inhalation of either volatile anaesthetic had no effect on muscle [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i in MHN muscle (Fig. 5A–D).

Fig 5.

(A) In vivo measurements of resting [Ca2+]i and (B) resting [Na+]i before and after exposure to 2 vol% halothane. (C,D) In vivo measurements of resting [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i before and after exposure to 1.5 vol% isoflurane. In all cases, resting values of [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i were significantly increased at rest (P<0.001) and both rose after exposure to halothane or isoflurane (P<0.001). [Ca2+]i, intracellular calcium; [Na+]i, intracellular sodium; HALO, halothane; ISO, isoflurane; MHN, MH normal; MHS-Hom, homozygous MHS; MHS-Het, heterozygous MHS.

Discussion

Major findings of the present study are as follows:

-

(i)

Mice with the RyR1 p.G2435R MH mutation appear grossly normal and can be bred to homozygosity, allowing the study of gene dose effects on physiology and pharmacology.

-

(ii)

There were unexpected deaths from no apparent cause in MHS-Hom animals, more frequent in males than in females, suggesting an association with either oestrogen production or a factor on the Y chromosome.

-

(iii)

MHS-Het and MHS-Hom myotubes have a lower threshold and EC50 for caffeine- and KCl-evoked Ca2+ release and a lower threshold for halothane evoked Ca2+ release.

-

(iv)

All MHS-Het and MHS-Hom animals died from heat stroke when exposed to increased ambient temperature (38°C) or in an MH crisis during halothane anaesthesia. MHS-Hets survived longer than MHS-Homs in both instances, but the increased time to death allowed MHS-Hets to develop higher body temperatures before succumbing. There was no effect of either increased ambient temperature or halothane anaesthesia in MHN animals.

-

(v)

MHS-Het and MHS-Hom adult muscle fibres in vivo have chronically elevated intracellular resting [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i (Hom>Het) compared with MHN muscle.

-

(vi)

MHS-Het and MHS-Hom adult muscle fibres in vivo increase their intracellular resting [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i (Hom>Het) after the animal is exposed to halothane or isoflurane anaesthesia, and die in an MH crisis.

We have shown that a common characteristic of MH-RyR1 and MH-CaV1.1 mutations is an inherited variant that disrupts both resting intracellular Ca2+ and Na+ homeostasis in skeletal muscle.14, 15, 18, 19 Calcium has a significant role in the regulation of numerous muscle processes including contraction, transcription factor regulation, metabolism, muscle plasticity, and survival.27 Muscle intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) is maintained at a low level (100–120 nM) in resting cells against a large concentration gradient (∼1 mM) in both the extracellular space and in the Ca2+ stores in the SR. Muscle [Ca2+]i is tightly regulated by complex regulatory mechanisms that balance Ca2+ influx and release from intracellular stores with intracellular sequestration and extracellular extrusion. Disturbance of the normal regulation of intracellular [Ca2+] (increased plasma membrane influx, increased release from intracellular stores, or both, and/or reduced uptake into SR) leads to a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i. The association between MH-RyR1 and MH-CaV1.1 mutations and intracellular Ca2+ dyshomeostasis has been validated in MHS patients,28 as well as in porcine and rodent models.14, 15, 18, 19, 20 We have also shown the role of sarcolemmal cation entry channels as significant contributors to chronically elevated [Ca2+]i both in quiescent MHS muscle fibres and during a fulminant MH episode.26

In humans, RYR1 p.G2434R is the most common globally reported variant associated with MH, although the data are biased because in the UK MH cohort, p.G2434R is present in approximately 16% of families21 and more than 50% of MH families worldwide that have been subjected to detailed genetic studies are from the UK. Of the probands subsequently found to harbour p.G2434R, 64% were male and 36% female, a distribution representative of all MH probands.29 There have been nine deaths associated with p.G2434R, five in males and four in females: the incidence of death of 8.5% is lower than the overall death rate from MH in the UK of 16% (unpublished data from P. Hopkins). The p.G2434R variant is not associated with muscle weakness but some patients report episodes of muscle pain and recurrent rhabdomyolysis.30 To date, p.G2434R has not been associated with exertional heat illness.

The caffeine sensitivity of myotubes from p.G2434R MHS-Het mice is nearer to that of MHN myotubes than we have previously observed in studies of myotubes from animals harbouring other RyR1 MH mutations.11 However, their responses to KCl showed an increased sensitivity and lower EC50 than the response in MHN myotubes, and these responses were similar to those observed in p.R163C murine myotubes.11

RyR1 p.G2435R MH muscle fibres in vivo have elevated resting [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i compared with MHN. [Ca2+]i was increased by 20% and 55% in MHS-Het and MHS-Hom muscle fibres, respectively, compared with MHN muscle fibres. Similarly, resting [Na+]i was increased by 20% and 41% in MHS-Het and MHS-Hom muscle fibres, respectively, compared with MHN muscle fibres. Although these intracellular ions are elevated compared with MHN, the p.G2435R MHS-Het elevations are not as high as we have reported in p.R163C23 and p.T4826I19 MHS-Het fibres, and the p.G2435R MHS-Hom elevations are not as high as were seen in pT4826I19 MHS-Hom fibres.

We observed a gene-dose effect for the p.G2435R mutation in response to halothane both in myotubes and in muscle fibres in vivo. The changes in [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i in muscle fibres in vivo in response to halothane for both Hom and Het p.G2435R were less than those for p.R163C MHS-Het fibres.23 Therefore, where we can make direct comparisons between p.G2435R, p.R163C, and p.T4826I mice, the data for resting [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i, halothane-evoked changes in [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i and responses to caffeine are consistent with a relatively weak phenotype associated with p.G2435R, mirroring observations in humans.22

Based on the extent of genotype–phenotype discordance31 in MH, evidence for multiple interacting genetic factors operating in individual MH families32, 33 and the quantitative differences in phenotype associated with different RYR1 variants,22 we proposed a threshold genetic model for MH susceptibility.22 In such a model, the clinical penetrance of RYR1 variants associated with a relatively weak functional effect may depend on the presence of other genetic, or indeed non-genetic, factors.2 RYR1 variants with a relatively weak phenotype, such as p.G2434R, would be expected to have a relatively high rate of genotype–phenotype discordance as we have observed.21 The ability to study gene dose effects, as afforded by the RYR1 p.G3425R mouse model, adds considerably to our ability to investigate a threshold genetic model.

The present study shows that RyR1 p.G2435R mice exhibit impairments in intracellular Ca2+ handling consistent with high resting [Ca2+]i at physiological temperature (37°C) and an abnormal elevation of intracellular Ca2+ upon exposure to anaesthetics or increased environmental temperature. One explanation for the combined elevation in [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i is increased activity in sarcolemmal non-specific cation channels (e.g. TRPC1, 3, and 6) in p.G2435R animals as we have reported in p.R163C and p.T4826I MHS animals.11, 16 If this explanation can be confirmed in future mechanistic studies, enhanced sarcolemmal Ca2+ and Na+ influx may emerge as a potential therapeutic target in MH with an RYR1 aetiology for variants affecting region 2 of the RyR1 protein as well as regions 1 and 3.

In conclusion, knock-in mice expressing the RyR1 mutation p.G2435R have elevated resting intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and are capable of developing a MH crisis upon exposure to halothane or isoflurane, whereas myotubes derived from their muscles demonstrate increased sensitivity to the effects of halothane, caffeine, and KCl. Comparison with data from knock-in mice expressing RyR1 p.R163C and RyR1 p.T4826I suggest similar genotype–phenotype relationships to the relevant isogenic human RYR1 variants found in patients susceptible to MH.

Authors' contributions

Conception and design of the study: J.R.L., P.M.H., P.D.A.

Conduct of experiments and data collection: J.R.L., V.K., C.P.D., P.D.A.

Data analysis and interpretation: all authors.

Drafting of manuscript: P.D.A., J.R.L., P.M.H.

Reviewed drafts of the manuscript and approved the final version: all authors

Declaration of interest

P.M.H. is an editorial board member of British Journal of Anaesthesia.

Funding

National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2P01 AR-05235; P.M.H., J.R.L., P.D.A.); National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (1R01AR068897-01A1; P.D.A., P.M.H., C.P.D.); Medical Research Council (MR/N002407/1; V.K., P.M.H., P.D.A.).

Editorial decision: July 16, 2018

Handling editor: H.C. Hemmings Jr

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.07.008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

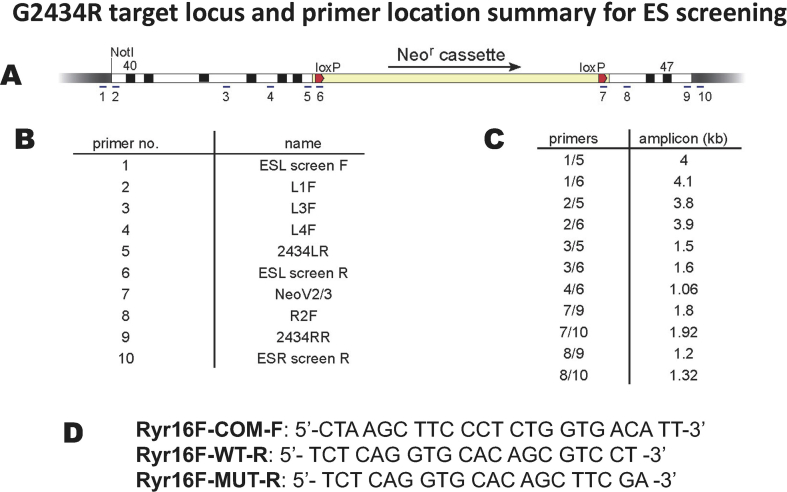

Fig S1.

A. Line figure showing the ES cell targeting sequence with a floxed G418 selection cassette. The mutation was made in exon 45 in the left arm of the targeting cassette. B: Numeral identification of primers used to confirm targeting of the mutant cassette. C: Primer pairs used to confirm homologous recombination by the targeting cassette. D: Primer pairs used for genotyping.

Fig S2.

Censored Kaplan-Meier survival curve for RYR1 p.G2435R knock-in mice. Curves are shown for male heterozygotes (Male HET, n=180), male homozygotes (Male HOM, n=94) and female homozygotes (Female HOM, n=88). The Male HET curve was significantly different to the other two curves (P < 0.00l1, log-rank test). The curves for wild type mice and female heterozygotes are identical to that of the male heterozygotes.

References

- 1.Hopkins P.M. Malignant hyperthermia: pharmacology of triggering. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:48–56. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riazi S., Kraeva N., Hopkins P.M. Malignant hyperthermia in the post-genomics era: new perspectives on an old concept. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:168–180. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurkat-Rott K., McCarthy T., Lehmann-Horn F. Genetics and pathogenesis of malignant hyperthermia. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:4–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200001)23:1<4::aid-mus3>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groom L., Muldoon S.M., Tang Z.Z. Identical de novo mutation in the type 1 ryanodine receptor gene associated with fatal, stress-induced malignant hyperthermia in two unrelated families. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:938–945. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182320068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jurkat-Rott K., Lerche H., Lehmann-Horn F. Skeletal muscle channelopathies. J Neurol. 2002;249:1493–1502. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Litman R.S., Rosenberg H. Malignant hyperthermia: update on susceptibility testing. JAMA. 2005;293:2918–2924. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.23.2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson R., Carpenter D., Shaw M.A., Halsall J., Hopkins P. Mutations in RYR1 in malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:977–989. doi: 10.1002/humu.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brady J.E., Sun L.S., Rosenberg H., Li G. Prevalence of malignant hyperthermia due to anesthesia in New York State, 2001–2005. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1162–1166. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181ac1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins P.M., Rüffert H., Snoeck M.M. The European Malignant Hyperthermia Group guidelines for the investigation of malignant hyperthermia susceptibility. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:531–539. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klingler W., Rueffert H., Lehmann-Horn F., Girard T., Hopkins P.M. Core myopathies and the risk of malignant hyperthermia. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1167–1173. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b5ae2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang T., Riehl J., Esteve E. Pharmacologic and functional characterization of malignant hyperthermia in the R163C RyR1 knock-in mouse. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1164–1175. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chelu M.G., Goonasekera S.A., Durham W.J. Heat- and anesthesia-induced malignant hyperthermia in an RyR1 knock-in mouse. FASEB J. 2006;20:329–330. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4497fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang D., Chen W., Xiao J. Reduced threshold for luminal Ca2+ activation of RyR1 underlies a causal mechanism of porcine malignant hyperthermia. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20813–20820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801944200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez J.R., Alamo L.A., Jones D.E. [Ca2+]i in muscles of malignant hyperthermia susceptible pigs determined in vivo with Ca2+ selective microelectrodes. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:85–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez J.R., Allen P.D., Alamo L., Jones D., Sreter F.A. Myoplasmic free [Ca2+] during a malignant hyperthermia episode in swine. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:82–88. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuen B., Boncompagni S., Feng W. Mice expressing T4826I-RYR1 are viable but exhibit sex- and genotype-dependent susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia and muscle damage. FASEB J. 2012;26:1311–1322. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-197582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du G.G., Sandhu B., Khanna V.K., Guo X.H., MacLennan D.H. Topology of the Ca2+ release channel of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum (RyR1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16725–16730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012688999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang T., Esteve E., Pessah I.N., Molinski T.F., Allen P.D., Lopez J.R. Elevated resting [Ca(2+)](i) in myotubes expressing malignant hyperthermia RyR1 cDNAs is partially restored by modulation of passive calcium leak from the SR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1591–C1598. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00133.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrientos G.C., Feng W., Truong K. Gene dose influences cellular and calcium channel dysregulation in heterozygous and homozygous T4826I-RYR1 malignant hyperthermia-susceptible muscle. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2863–2876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.307926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eltit J.M., Bannister R.A., Moua O. Malignant hyperthermia susceptibility arising from altered resting coupling between the skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel and the type 1 ryanodine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:7923–7928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119207109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller D.M., Daly C., Aboelsaod E.M. Genetic epidemiology of malignant hyperthermia in the United Kingdom. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:944–952. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter D., Robinson R.L., Quinnell R.J. Genetic variation in RYR1 and malignant hyperthermia phenotypes. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:538–548. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altamirano F., Eltit J.M., Robin G. Ca2+ influx via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is enhanced in malignant hyperthermia skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:19180–19190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.550764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoelting R.K. Halothane and methoxyflurane concentrations in end-tidal gas, arterial blood, and lumbar cerebrospinal fluid. Anesthesiology. 1973;38:384–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez J.R., Alamo L., Caputo C., DiPolo R., Vergara S. Determination of ionic calcium in frog skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1983;43:1–4. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eltit J.M., Ding X., Pessah I.N., Allen P.D., Lopez J.R. Nonspecific sarcolemmal cation channels are critical for the pathogenesis of malignant hyperthermia. FASEB J. 2013;27:991–1000. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-218354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tu M.K., Levin J.B., Hamilton A.M., Borodinsky L.N. Calcium signaling in skeletal muscle development, maintenance and regeneration. Cell Calcium. 2016;59:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez J.R., Alamo L., Caputo C., Wikinski J., Ledezma D. Intracellular ionized calcium concentration in muscles from humans with malignant hyperthermia. Muscle Nerve. 1985;8:355–358. doi: 10.1002/mus.880080502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis F.R., Halsall P.J., Harriman D.G. The work of the Leeds malignant hyperpyrexia unit, 1971–84. Anaesthesia. 1986;41:809–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb13122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dlamini N., Voermans N.C., Lillis S. Mutations in RYR1 are a common cause of exertional myalgia and rhabdomyolysis. Neuromus Disord. 2013;23:540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson R.L., Anetseder M.J., Brancadoro V. Recent advances in the diagnosis of malignant hyperthermia susceptibility: how confident can we be of genetic testing? Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:342–348. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson R.L., Curran J.L., Ellis F.R. Multiple interacting gene products may influence susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia. Ann Hum Genet. 2000;64:307–320. doi: 10.1017/S0003480000008186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson R., Hopkins P.M., Carsana A. Several interacting genes influence the malignant hyperthermia phenotype. Hum Genet. 2003;112:217–218. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0864-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]