Abstract

Context:

The advent of Web-based sports injury surveillance via programs such as the High School Reporting Information Online system and the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program has aided the acquisition of girls' and women's soccer injury data.

Objective:

To describe the epidemiology of injuries sustained in high school girls' soccer in the 2005–2006 through 2013–2014 academic years and collegiate women's soccer in the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years using Web-based sports injury surveillance.

Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Setting:

Online injury surveillance from soccer teams in high school girls (annual average = 100) and collegiate women (annual average = 52).

Patients or Other Participants:

Female high school and collegiate soccer players who participated in practices or competitions during the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

Athletic trainers collected time-loss (≥24 hours) injury and exposure data. Injury rates per 1000 athlete-exposures (AEs), injury rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), injury proportions by body site, and diagnoses were calculated.

Results:

The High School Reporting Information Online system documented 3242 time-loss injuries during 1 393 753 AEs; the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program documented 5092 time-loss injuries during 772 048 AEs. Injury rates were higher in college than in high school (6.60 versus 2.33/1000 AEs; IRR = 2.84; 95% CI = 2.71, 2.96), and during competitions than during practices in high school (IRR = 4.88; 95% CI = 4.54, 5.26) and college (IRR = 2.93; 95% CI = 2.77, 3.10). Most injuries at both levels affected the lower extremity and were ligament sprains or muscle/tendon strains. Concussions accounted for 24.5% of competition injuries in high school but 14.6% of competition injuries in college. More than one-third of competition injuries to high school goalkeepers were concussions.

Conclusions:

Injury rates were higher in college versus high school and during competitions versus practices. These differences may be attributable to differences in reporting, activity intensity, and game-play skill level. The high incidence of lower extremity injuries and concussions in girls' and women's soccer, particularly concussions in high school goalkeepers, merits further exploration and identification of prevention strategies.

Key Words: female athletes, lower extremity injuries, concussions

Key Points

The rate of injury in collegiate women's soccer exceeded that in high school girls' soccer.

Competition injury rates were higher than practice injury rates.

At the high school level, concussions accounted for nearly a quarter of competition injuries.

The large numbers of female soccer student-athletes at the high school and collegiate levels highlight the growing popularity of girls' and women's participation in soccer in the United States. A total of 374 564 female student-athletes participated in high school soccer during the 2013–2014 academic year, which is a 10% increase since 2008–2009.1 Of the 1113 member institutions of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in the 2013–2014 academic year, 91.8% had a women's soccer program, for a total of 26 358 women's soccer student-athletes.2 Compared with the 2003–2004 academic year, the number of female high school and collegiate soccer student-athletes had increased in the 2013–2014 academic year by 29.0% and 21.2%, respectively.1

Given the growth in participants, we require data on the incidence and nature of injuries in the sport, so that injury-prevention interventions can be appropriately tailored to the needs of the populations. The NCAA has used injury surveillance to acquire collegiate sports injury data since the 1980s. Although this NCAA-based surveillance system has had several names, we herein denote it as the NCAA Injury Surveillance Program (ISP). Since the 2004–2005 academic year, the NCAA has used a Web-based platform to collect collegiate sports injury and exposure data via athletic trainers (ATs).3 A year later, High School Reporting Information Online (HS RIO), a similar Web-based high school sports injury surveillance system, was launched.4

As denoted in the van Mechelen et al5 framework, injury prevention benefits from ongoing monitoring of injury incidence, and updated descriptive epidemiology is needed. A previous NCAA-ISP report6 for the 1988–1989 through 2002–2003 academic years documented women's soccer competition and practice injury rates of 16.44 and 5.23, respectively, per 1000 athlete-exposures (AEs). However, over the past decade, numerous efforts to implement injury prevention in soccer have occurred; these included programming specific to soccer7–11 as well as initiatives across all sports (eg, concussion legislation).12,13 Similarly, documenting injuries through high school sports injury surveillance is important to establish injury incidence estimates and compare findings between the high school and collegiate settings. The purpose of this article is to summarize the descriptive epidemiology of injuries sustained in high school girls' and collegiate women's soccer during the first decade of Web-based sports injury surveillance (2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years).

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Period

This study used data collected by HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP, sports injury-surveillance programs for the high school and collegiate levels, respectively. Use of the HS RIO data was approved by the Nationwide Children's Hospital Subjects Review Board (Columbus, OH). Use of the NCAA-ISP data was approved by the Research Review Board at the NCAA.

An average of 100 high schools sponsoring girls' soccer provided data to the HS RIO random sample during the 2005–2006 through 2013–2014 academic years (2005–2006 was the first year HS RIO collected data). An average of 52 NCAA member institutions (Division I = 21, Division II = 7, Division III = 24) sponsoring women's soccer participated in the NCAA-ISP during the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years. The methods of HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP are summarized in the following sections. In-depth information on the methods and analyses for this special series of articles on Web-based sports injury surveillance can be found in the previously published methodologic article.14 In addition, previous publications have described the sampling and data collection of HS RIO4,15 and the NCAA-ISP3 in depth.

High School RIO

High School RIO consists of a sample of high schools with 1 or more National Athletic Trainers' Association–affiliated ATs with valid e-mail addresses. The ATs from participating high schools reported injury incidence and AE information weekly throughout the academic year using a secure Web site. For each injury, the AT completed a detailed report on the injured athlete (age, height, weight, etc), the injury (site, diagnosis, severity, etc), and the injury event (activity, mechanism, etc). Throughout each academic year, participating ATs were able to view and update previously submitted reports with new information (eg, time loss) as needed.

Data for HS RIO during the 2005–2006 through 2013–2014 academic years originated from a random sample of 100 schools that were recruited annually. Eligible schools were randomly selected from 8 strata (12 or 13 per stratum) based on school population (enrollment ≤1000 or >1000) and US Census geographic region.16 Athletic trainers from these schools reported data for the 9 sports of interest (boys' baseball, basketball, football, soccer, and wrestling and girls' basketball, soccer, softball, and volleyball). If a school dropped out of the system, a replacement from the same stratum was selected.

In HS RIO, national injury estimates were calculated from injury counts obtained from the sample. A weighting algorithm based on the inverse probability of participant schools' selection into the study (based on geographic location and high school size) was applied to individual case counts in order to calculate the national injury estimates.

The NCAA-ISP

The NCAA-ISP depends on a convenience sample of teams with ATs voluntarily reporting injury and exposure data.3 Participation in the NCAA-ISP, although voluntary, is available to all NCAA institutions. For each injury event, the AT completes a detailed report on the injury or condition (eg, site, diagnosis) and the circumstances (eg, activity, mechanism, event type [ie, competition or practice]). The ATs are able to view and update previously submitted information as needed during the course of a season. In addition, ATs also provide the number of student-athletes participating in each practice and competition. Data collection for the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years is described in the following paragraphs.

During the 2004–2005 through 2008–2009 academic years, ATs used a Web-based platform launched by the NCAA to track injury and exposure data.3 This platform integrated some of the functional components of an electronic medical record, such as athlete demographic information and preseason injury information. During the 2009–2010 through 2013–2014 academic years, the Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention, Inc (Datalys Center, Indianapolis, IN), introduced a common data element (CDE) standard to improve process flow. The CDE standard allowed data to be gathered from different electronic medical record and injury-documentation applications, including the Athletic Trainer System (Keffer Development, Grove City, PA), the Injury Surveillance Tool (Datalys Center), and the Sports Injury Monitoring System (FlanTech, Iowa City, IA). The CDE export standard allowed ATs to document injuries as they normally would as part of their daily clinical practice, as opposed to asking them to report injuries solely for purposes of participation in an injury-surveillance program. Data were deidentified and sent to the Datalys Center, where they were examined by data quality-control staff and a verification engine.

To calculate national estimates of the number of injuries and AEs, poststratification sample weights, based on sport, division, and academic year, were applied to each reported injury and AE. Weights for all data were further adjusted to correct for underreporting, according to findings from Kucera et al,17 who estimated that the ISP captured 88.3% of all time-loss medical-care injury events. Weighted counts were scaled up by a factor of (0.883−1). In-depth information on the formula used to calculate national estimates can be found in the previously published methodologic article.14

Definitions

Injury.

A reportable injury in both HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP was defined as an injury that (1) occurred as a result of participation in an organized practice or competition, (2) required medical attention by a certified AT or physician, and (3) resulted in restriction of the student-athlete's participation for 1 or more days beyond the day of injury. Since the 2007–2008 academic year, HS RIO has also captured all concussions, fractures, and dental injuries, regardless of time loss. In the NCAA-ISP, multiple injuries occurring from 1 injury event could be included, whereas in HS RIO, only the principal injury was captured. Beginning in the 2009–2010 academic year, the NCAA-ISP also began to monitor all non–time-loss injuries. A non–time-loss injury was defined as any injury that was evaluated or treated (or both) by an AT or physician but did not result in restriction from participation beyond the day of injury. However, because HS RIO captures only time-loss injuries (to reduce the time burden on high school ATs), for this series of publications, only time-loss injuries (with the exception of concussions, fractures, and dental injuries as noted earlier) were included.

Athlete-Exposure.

For both surveillance systems, a reportable AE was defined as 1 student-athlete participating in 1 school-sanctioned practice or competition in which he or she was exposed to the possibility of athletic injury, regardless of the time associated with that participation. Preseason scrimmages were considered practice exposures, not competition exposures.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS-Enterprise Guide software (version 5.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Because the data collected from HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP are similar, we opted to recode data when necessary to increase the comparability between high school and collegiate student-athletes. We also opted to ensure that categorizations were consistent among all sport-specific articles within this special series. Because methodologic variations may lead to small differences in injury reporting between these surveillance systems, caution must be taken when interpreting the results.

We examined injury counts, national estimates, and distributions by event type (practice or competition), time in season (preseason, regular season, postseason), time loss (1–6 days; 7–21 days; more than 21 days, including injuries resulting in a premature end to the season), body part injured, diagnosis, mechanism of injury, activity during injury, and position. We also calculated injury rates per 1000 AEs and injury rate ratios (IRRs). The IRRs focused on comparisons by level of play (high school and college), event type (practice and competition), school size in high school (≤1000 and >1000 students), division in college (Division I, II, and III), and time in season (preseason, regular season, and postseason). All IRRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) not containing 1.0 were considered statistically significant.

Last, we used linear regression to analyze linear trends across time of injury rates and compute average annual changes (ie, mean differences). Because of the 2 data-collection methods for the NCAA-ISP during the 2004–2005 through 2008–2009 and 2009–2010 through 2013–2014 academic years, linear trends were conducted separately for each time period. All mean differences with 95% CIs not containing 0.0 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Total Injury Frequency, National Estimates, and Injury Rates

During the 2005–2006 through 2013–2014 academic years, ATs reported a total of 3242 time-loss injuries in high school girls' soccer (Table 1). During the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years, ATs reported a total of 5092 injuries in collegiate women's soccer (Table 1). This equated to a national estimate of 1 874 022 high school injuries (annual average of 208 225) and 97 074 collegiate injuries (annual average of 9707).

Table 1.

Injury Rates by School Size or Division and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Girls' and Collegiate Women's Soccera

| Surveillance System and School Size or Division |

Exposure Type |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Athlete-Exposures |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

| HS RIO (2005–2006 through 2013–2014) | |||||

| ≤1000 students | Practice | 449 (32.0) | 415 780 (31.0) | 338 126 | 1.33 (1.21, 1.45) |

| Competition | 956 (68.0) | 925 751 (69.0) | 152 947 | 6.25 (5.85, 6.65) | |

| Total | 1405 (100.0) | 1 341 531 (100.0) | 491 073 | 2.86 (2.71, 3.01) | |

| >1000 students | Practice | 599 (32.6) | 174 652 (32.8) | 637 447 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.01) |

| Competition | 1238 (67.4) | 357 839 (67.2) | 265 233 | 4.67 (4.41, 4.93) | |

| Total | 1837 (100.0) | 532 491 (100.0) | 902 680 | 2.04 (1.94, 2.13) | |

| Total | Practice | 1048 (32.3) | 5904 32 (31.5) | 975 573 | 1.07 (1.01, 1.14) |

| Competition | 2194 (67.7) | 1 283 590 (68.5) | 418 180 | 5.25 (5.03, 5.47) | |

| Total | 3242 (100.0) | 1 874 022 (100.0) | 1 393 753 | 2.33 (2.25, 2.41) | |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | |||||

| Division I | Practice | 1151 (50.7) | 17 348 (50.9) | 260 471 | 4.42 (4.16, 4.67) |

| Competition | 1117 (49.3) | 16 766 (49.1) | 80 428 | 13.89 (13.07, 14.70) | |

| Total | 2268 (100.0) | 34 114 (100.0) | 340 899 | 6.65 (6.38, 6.93) | |

| Division II | Practice | 335 (51.0) | 11 036 (50.4) | 89 571 | 3.74 (3.34, 4.14) |

| Competition | 322 (49.0) | 10 875 (49.6) | 27 037 | 11.91 (10.61, 13.21) | |

| Total | 657 (100.0) | 21 911 (100.0) | 116 608 | 5.63 (5.20, 6.07) | |

| Division III | Practice | 1126 (52.0) | 20 962 (51.1) | 233 057 | 4.83 (4.55, 5.11) |

| Competition | 1041 (48.0) | 20 087 (48.9) | 81 485 | 12.78 (12.00, 13.55) | |

| Total | 2167 (100.0) | 41 049 (100.0) | 314 542 | 6.89 (6.60, 7.18) | |

| Total | Practice | 2612 (51.3) | 49 347 (50.8) | 583 099 | 4.48 (4.31, 4.65) |

| Competition | 2480 (48.7) | 47 727 (49.2) | 188 950 | 13.13 (12.61, 13.64) | |

| Total | 5092 (100.0) | 97 074 (100.0) | 772 048 | 6.60 (6.41, 6.78) | |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition, (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional, and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event. National estimates and athlete-exposures may not sum to totals because of rounding error.

The total injury rate for high school girls' soccer was 2.33/1000 AEs (95% CI = 2.25, 2.41). The total injury rate for collegiate women's soccer was 6.60/1000 AEs (95% CI = 6.41, 6.78). The total injury rate was nearly 3 times as high in college as in high school (IRR = 2.84; 95% CI = 2.71, 2.96).

School Size and Division

In high school girls' soccer, the total injury rate was higher in high schools with ≤1000 students than in those with >1000 students (IRR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.31, 1.51; Table 1). In collegiate women's soccer, Division I had a higher total injury rate than Division II (IRR = 1.18; 95% CI = 1.08, 1.29) but not Division III (IRR = 0.97; 95% CI = 0.91, 1.02). Also, Division III had a higher total injury rate than Division II (IRR = 1.22; 95% CI = 1.12, 1.33).

Event Type

The majority of injuries occurred during competitions in high school (67.7%) and during practices in college (51.3%; Table 1). The competition injury rate was higher than the practice injury rate at both the high school (IRR = 4.88; 95% CI = 4.54, 5.26) and collegiate (IRR = 2.93; 95% CI = 2.77, 3.10) levels.

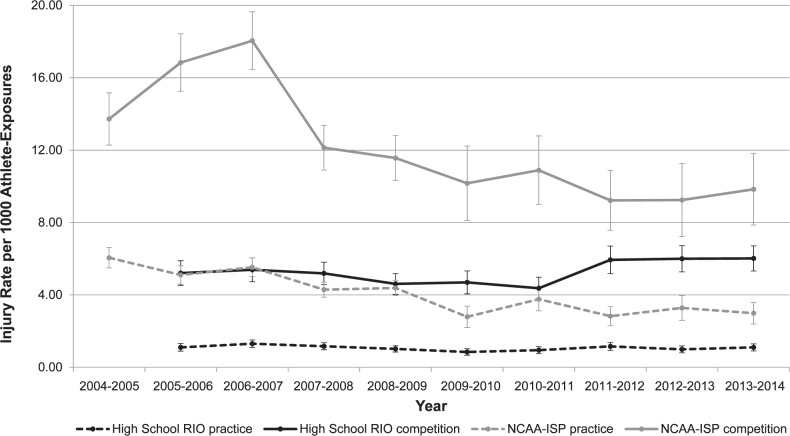

No linear trends were found in the annual injury rates for high school practices (annual average change = −0.02/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.05, 0.01) or competitions (annual average change = 0.11/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.03, 0.24; Figure). A significant trend was present in the 2004–2005 through 2008–2009 academic years for practices (annual average change = −0.42/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.62, −0.21) but not for competitions (annual average change = −0.90/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −2.28, 0.48). No linear trends were observed in the 2009–2010 through 2013–2014 academic years for practices (annual average change of 0.15/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.36, 0.05) or competitions (annual average change = 0.03/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.44, 0.51).

Figure.

Injury rates by year and type of athlete-exposure (AE) in high school girls' and collegiate women's soccer. Note: Annual average changes for linear trend test for injury rates are as follows: High School Reporting Information Online (RIO; practices = −0.02/1000 AEs, 95% confidence interval [CI] = −0.05, 0.01; competitions = 0.11/1000 AEs, 95% CI = −0.03, 0.24); National Collegiate Athletic Association–Injury Surveillance Program (NCAA-ISP) 2004–2005 through 2008–2009 (practices = −0.42/1000 AEs, 95% CI = −0.62, −0.21; competitions = −0.90/1000 AEs, 95% CI = −2.28, 0.48); NCAA-ISP 2009–2010 through 2013–2014 academic years (practices = −0.15/1000 AEs, 95% CI = −0.36, 0.05; competitions = 0.03/1000 AEs, 95% CI = −0.44, 0.51). A negative rate indicates a decrease in the annual average change between years, and a positive rate indicates an increase in the annual average change; 95% CIs that include 0.00 are not significant.

Time in Season

Among both high school and collegiate athletes, the majority of injuries occurred during the regular season (high school = 77.7%, college = 63.4%; Table 2). At the collegiate level, the preseason had a higher injury rate than the regular season (IRR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.28, 1.44) and postseason (IRR = 2.06; 95% CI = 1.76, 2.40). In addition, the injury rate was higher in the regular season than in the postseason (IRR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.31, 1.77). Injury rates by time in season could not be calculated for high school as AEs were not stratified by time in season.

Table 2.

Injury Rates by Time in Season and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Girls' and Collegiate Women's Soccera

| Time in Season |

Exposure Type |

HS RIO (2005–2006 Through 2013–2014) |

NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 Through 2013–2014) |

||||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Athlete- Exposures |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

| Preseason | Practice | 472 (82.1) | 241 277 (81.2) | 1582 (94.0) | 29 589 (94.4) | 197 263 | 8.02 (7.62, 8.41) |

| Competition | 103 (17.9) | 55 722 (18.8) | 101 (6.0) | 1758 (5.6) | 4967 | 20.33 (16.37, 24.30) | |

| Total | 575 (100.0) | 296 999 (100.0) | 1683 (100.0) | 31 347 (100.0) | 202 230 | 8.32 (7.92, 8.72) | |

| Regular season | Practice | 553 (22.0) | 330 058 (22.2) | 973 (30.1) | 18 605 (29.9) | 352 922 | 2.76 (2.58, 2.93) |

| Competition | 1959 (78.0) | 1 154 980 (77.8) | 2256 (69.9) | 43 581 (70.1) | 172 392 | 13.09 (12.55, 13.63) | |

| Total | 2512 (100.0) | 1 485 038 (100.0) | 3229 (100.0) | 62 186 (100.0) | 525 314 | 6.15 (5.93, 6.36) | |

| Postseason | Practice | 16 (11.1) | 11 171 (13.7) | 57 (31.7) | 1152 (32.5) | 32 913 | 1.73 (1.28, 2.18) |

| Competition | 128 (88.9) | 70 194 (86.3) | 123 (68.3) | 2388 (67.5) | 11 590 | 10.61 (8.74, 12.49) | |

| Total | 144 (100.0) | 81 365 (100.0) | 180 (100.0) | 3540 (100.0) | 44 504 | 4.04 (3.45, 4.64) | |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excludes 6 injuries reported in HS RIO because of missing data for time in season. Injury rates by time in season could not be calculated for high school as athlete-exposures were not stratified by time in season. National estimates and athlete-exposures may not sum to totals because of rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition, (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional, and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Time Loss From Participation

In both high school and college, the largest proportion of injuries resulted in time loss of less than 1 week, ranging from 37.7% of injuries in high school competitions to 57.6% of injuries in collegiate practices (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of Injuries and Injury Rates by Time Loss and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Girls' and Collegiate Women's Soccera

| Surveillance System and Time-Loss Category |

Practice |

Competition |

||||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2005–2006 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| 1 d to <1 wk | 494 (49.1) | 288 792 (50.8) | 0.51 (0.46, 0.55) | 788 (37.7) | 481 600 (39.2) | 1.88 (1.75, 2.02) |

| 1 to 3 wk | 356 (35.4) | 197 163 (34.7) | 0.36 (0.33, 0.40) | 775 (37.1) | 438 321 (35.6) | 1.85 (1.72, 1.98) |

| >3 wkb | 156 (15.5) | 82 792 (14.6) | 0.16 (0.13, 0.18) | 528 (25.3) | 310 365 (25.2) | 1.26 (1.15, 1.37) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| 1 d to <1 wk | 1466 (57.6) | 28 346 (59.2) | 2.51 (2.39, 2.64) | 1377 (56.6) | 25 823 (55.4) | 7.29 (6.90, 7.67) |

| 1 to 3 wk | 747 (29.4) | 13 421 (28.0) | 1.28 (1.19, 1.37) | 732 (30.1) | 13 384 (28.7) | 3.87 (3.59, 4.15) |

| >3 wkb | 332 (13.1) | 6123 (12.8) | 0.57 (0.51, 0.63) | 323 (13.3) | 7398 (15.9) | 1.71 (1.52, 1.90) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excludes 145 injuries reported in HS RIO and 115 injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP because of missing data for time loss. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 because of rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition, (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional, and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Includes injuries that resulted in time loss over 3 weeks, medical disqualification, the athlete choosing not to continue, the athlete being released from the team, or the season ending before the athlete returned to activity.

Body Parts Injured and Diagnoses

High School.

The most commonly injured body parts during practices were the ankle (24.7%), hip/thigh/upper leg (21.4%), and knee (15.2%); during competitions, the most frequently injured body parts were the head/face (27.7%), knee (21.8%), and ankle (20.3%; Table 4). The injury diagnosis reported most often during practices and competitions was ligament sprains (practices = 32.4%, competitions = 34.5%; Table 5). Other typical injury diagnoses were muscle/tendon strains (28.0%) during practices and concussions (24.5%) during competitions.

Table 4.

Number of Injuries, National Estimates, and Injury Rates by Body Part Injured and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Girls' and Collegiate Women's Soccera

| Surveillance System and Body Part Injured |

Practice |

Competition |

||||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2005–2006 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| Head/face | 103 (9.8) | 54 592 (9.3) | 0.11 (0.09, 0.13) | 607 (27.7) | 340 550 (26.6) | 1.45 (1.34, 1.57) |

| Neck | 3 (0.3) | 786 (0.1) | <0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 18 (0.8) | 7672 (0.6) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) |

| Shoulder/clavicle | 20 (1.9) | 9441 (1.6) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 37 (1.7) | 20 594 (1.6) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.12) |

| Arm/elbow | 11 (1.1) | 6892 (1.2) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 31 (1.4) | 17 516 (1.4) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.10) |

| Hand/wrist | 35 (3.3) | 18 656 (3.2) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.05) | 84 (3.8) | 50 183 (3.9) | 0.20 (0.16, 0.24) |

| Trunk | 38 (3.6) | 21 058 (3.6) | 0.04 (0.03, 0.05) | 59 (2.7) | 33 995 (2.7) | 0.14 (0.11, 0.18) |

| Hip/thigh/upper leg | 224 (21.4) | 117 307 (19.9) | 0.23 (0.20, 0.26) | 208 (9.5) | 132 385 (10.3) | 0.50 (0.43, 0.56) |

| Knee | 159 (15.2) | 93 212 (15.8) | 0.16 (0.14, 0.19) | 478 (21.8) | 259 587 (20.3) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.25) |

| Lower leg | 105 (10.0) | 65 414 (11.1) | 0.11 (0.09, 0.13) | 117 (5.3) | 65 481 (5.1) | 0.28 (0.23, 0.33) |

| Ankle | 258 (24.7) | 138 961 (23.6) | 0.26 (0.23, 0.30) | 445 (20.3) | 287 658 (22.5) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.16) |

| Foot | 78 (7.5) | 54 014 (9.2) | 0.08 (0.06, 0.10) | 99 (4.5) | 56 334 (4.4) | 0.24 (0.19, 0.28) |

| Other | 12 (1.1) | 9042 (1.5) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | 7 (0.3) | 8162 (0.6) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.03) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| Head/face | 194 (7.4) | 3884 (7.9) | 0.33 (0.29, 0.38) | 476 (19.2) | 10 316 (21.6) | 2.52 (2.29, 2.75) |

| Neck | 14 (0.5) | 216 (0.4) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) | 30 (1.2) | 496 (1.0) | 0.16 (0.10, 0.22) |

| Shoulder/clavicle | 42 (1.6) | 789 (1.6) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.09) | 72 (2.9) | 1335 (2.8) | 0.38 (0.29, 0.47) |

| Arm/elbow | 22 (0.8) | 420 (0.9) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.05) | 30 (1.2) | 544 (1.1) | 0.16 (0.1, 0.22) |

| Hand/wrist | 47 (1.8) | 978 (2.0) | 0.08 (0.06, 0.10) | 61 (2.5) | 1165 (2.4) | 0.32 (0.24, 0.4) |

| Trunk | 154 (5.9) | 3019 (6.1) | 0.26 (0.22, 0.31) | 116 (4.7) | 2044 (4.3) | 0.61 (0.50, 0.73) |

| Hip/thigh/upper leg | 782 (29.9) | 15 155 (30.7) | 1.34 (1.25, 1.44) | 375 (15.1) | 6853 (14.4) | 1.98 (1.78, 2.19) |

| Knee | 401 (15.4) | 7261 (14.7) | 0.69 (0.62, 0.76) | 447 (18.0) | 9239 (19.4) | 2.37 (2.15, 2.59) |

| Lower leg | 219 (8.4) | 3861 (7.8) | 0.38 (0.33, 0.43) | 181 (7.3) | 3286 (6.9) | 0.96 (0.82, 1.10) |

| Ankle | 434 (16.6) | 7919 (16.0) | 0.74 (0.67, 0.81) | 525 (21.2) | 9716 (20.4) | 2.78 (2.54, 3.02) |

| Foot | 202 (7.7) | 3850 (7.8) | 0.35 (0.30, 0.39) | 138 (5.6) | 2200 (4.6) | 0.73 (0.61, 0.85) |

| Other | 101 (3.9) | 1996 (4.0) | 0.17 (0.14, 0.21) | 29 (1.2) | 533 (1.1) | 0.15 (0.10, 0.21) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excludes 6 injuries reported in HS RIO because of missing data for body part. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 because of rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition, (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional, and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Table 5.

Number of Injuries, National Estimates, and Injury Rates by Diagnosis and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Girls' and Collegiate Women's Soccera

| Surveillance System and Diagnosis |

Practice |

Competition |

||||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2005–2006 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| Concussion | 90 (8.6) | 48 068 (8.1) | 0.09 (0.07, 0.11) | 537 (24.5) | 307 443 (24.0) | 1.28 (1.18, 1.39) |

| Contusion | 65 (6.2) | 33 740 (5.7) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.08) | 291 (13.3) | 163 039 (12.7) | 0.70 (0.62, 0.78) |

| Dislocationb | 9 (0.9) | 5590 (1.0) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 20 (0.9) | 10 603 (0.8) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.07) |

| Fracture/avulsion | 58 (5.5) | 30 956 (5.2) | 0.06 (0.04, 0.07) | 157 (7.2) | 83 478 (6.5) | 0.38 (0.32, 0.43) |

| Laceration | 1 (0.1) | 359 (0.1) | <0.01 (0.00, <0.01) | 12 (0.6) | 6616 (0.5) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.04) |

| Ligament sprain | 339 (32.4) | 188 114 (31.9) | 0.35 (0.31, 0.38) | 756 (34.5) | 454 746 (35.5) | 1.81 (1.68, 1.94) |

| Muscle/tendon strain | 293 (28.0) | 164 041 (27.8) | 0.30 (0.27, 0.33) | 245 (11.2) | 153 064 (12.0) | 0.59 (0.51, 0.66) |

| Other | 192 (18.3) | 119 418 (20.2) | 0.20 (0.17, 0.22) | 172 (7.9) | 102 385 (8.0) | 0.41 (0.35, 0.47) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| Concussion | 136 (5.2) | 2842 (5.8) | 0.23 (0.19, 0.27) | 361 (14.6) | 7826 (16.4) | 1.91 (1.71, 2.11) |

| Contusion | 218 (8.4) | 3664 (7.4) | 0.37 (0.32, 0.42) | 529 (21.3) | 9032 (18.9) | 2.80 (2.56, 3.04) |

| Dislocationb | 8 (0.3) | 144 (0.3) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 16 (0.7) | 289 (0.6) | 0.08 (0.04, 0.13) |

| Fracture/avulsion | 59 (2.3) | 1288 (2.6) | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) | 111 (4.5) | 2384 (5.0) | 0.59 (0.48, 0.70) |

| Laceration | 9 (0.3) | 118 (0.2) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 24 (1.0) | 417 (0.9) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.18) |

| Ligament sprain | 620 (23.7) | 12 198 (24.7) | 1.06 (0.98, 1.15) | 740 (29.8) | 15 085 (31.6) | 3.92 (3.63, 4.20) |

| Muscle/tendon strain | 792 (30.3) | 15 765 (32.0) | 1.36 (1.26, 1.45) | 318 (12.8) | 6186 (13.0) | 1.68 (1.50, 1.87) |

| Other | 770 (29.5) | 13 329 (27.0) | 1.32 (1.23, 1.41) | 381 (15.4) | 6508 (13.6) | 2.02 (1.81, 2.22) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excludes 5 injuries reported in HS RIO because of missing data for diagnosis. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 because of rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition, (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional, and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Includes separations.

College.

The most commonly injured body parts during practices and competitions were the hip/thigh/upper leg (practices = 29.9%, competitions = 15.1%), ankle (practices = 16.6%, competitions = 21.2%), and knee (practices = 15.4%, competitions = 18.0%; Table 4). During competitions, 19.2% of injuries were to the head/face. The most frequent injury diagnoses during practices were muscle/tendon strains (30.3%) and ligament sprains (23.7%); in competitions, they were ligament sprains (29.8%) and contusions (21.3%), followed by concussions (14.6%; Table 5).

Mechanisms of Injury and Activities

High School.

The mechanisms of injury cited most often during practices and competitions were no contact (practices = 34.8%; competitions = 17.2%) and contact with another person (practices = 19.2%; competitions = 54.5%; Table 6). The most common activity during injury in practices and competitions was general play (practices = 32.2%; competitions = 19.8%; Table 7). Other typical activities during injury were conditioning (16.1%) in practice and defending (19.0%) and chasing loose balls (13.8%) in competitions.

Table 6.

Number of Injuries, National Estimates, and Injury Rates by Mechanism of Injury and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Girls' and Collegiate Women's Soccera

| Surveillance System and Mechanism of Injury |

Practice |

Competition |

||||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2005–2006 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| Contact with another person | 196 (19.2) | 96 059 (16.7) | 0.20 (0.17, 0.23) | 1177 (54.5) | 670 108 (53.0) | 2.81 (2.65, 2.98) |

| Contact with playing surface | 164 (16.1) | 110 181 (19.2) | 0.17 (0.14, 0.19) | 316 (14.6) | 191 766 (15.2) | 0.76 (0.67, 0.84) |

| Contact with soccer ball | 110 (10.8) | 62 662 (10.9) | 0.11 (0.09, 0.13) | 223 (10.3) | 138 211 (10.9) | 0.53 (0.46, 0.60) |

| Contact with goal | 3 (0.3) | 1654 (0.3) | <0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 5 (0.2) | 3475 (0.3) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) |

| Contact with other playing equipment | 11 (1.1) | 5847 (1.0) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 11 (0.5) | 6442 (0.5) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.04) |

| Contact with out of bounds object | 1 (0.1) | 505 (0.1) | <0.01 (0.00, <0.01) | 1 (0.1) | 973 (0.1) | <0.01 (0.00, 0.01) |

| No contact | 355 (34.8) | 183 698 (32.0) | 0.36 (0.33, 0.40) | 371 (17.2) | 217 637 (17.2) | 0.89 (0.80, 0.98) |

| Overuse/chronic | 157 (15.4) | 100 471 (17.5) | 0.16 (0.14, 0.19) | 48 (2.2) | 29 398 (2.3) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.15) |

| Illness/infection | 22 (2.2) | 12 943 (2.3) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 6 (0.3) | 6186 (0.5) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.03) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| Contact with another person | 486 (19.0) | 8812 (18.4) | 0.83 (0.76, 0.91) | 1315 (53.6) | 25 049 (53.5) | 6.96 (6.58, 7.34) |

| Contact with playing surface | 306 (12.0) | 6211 (13.0) | 0.52 (0.47, 0.58) | 368 (15.0) | 7189 (15.4) | 1.95 (1.75, 2.15) |

| Contact with soccer ball | 296 (11.6) | 6011 (12.6) | 0.51 (0.45, 0.57) | 189 (7.7) | 3962 (8.5) | 1.00 (0.86, 1.14) |

| Contact with goal | 6 (0.2) | 65 (0.1) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 7 (0.3) | 126 (0.3) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.06) |

| Contact with other playing equipment | 7 (0.3) | 145 (0.3) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 4 (0.2) | 43 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) |

| Contact with out of bounds object | 1 (0.0) | 69 (0.1) | <0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 1 (0.0) | 9 (0.0) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) |

| No contact | 980 (38.3) | 17 835 (37.1) | 1.68 (1.58, 1.79) | 442 (18.0) | 8251 (17.6) | 2.34 (2.12, 2.56) |

| Overuse/chronic | 355 (13.9) | 6735 (14.1) | 0.61 (0.55, 0.67) | 103 (4.2) | 1718 (3.7) | 0.55 (0.44, 0.65) |

| Illness/infection | 121 (4.7) | 2020 (4.2) | 0.21 (0.17, 0.24) | 24 (1.0) | 452 (1.0) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.18) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Mechanism of injury excludes 65 injuries reported in HS RIO and 81 injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP because of missing data or athletic trainer reporting Other or Unknown. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 because of rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition, (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional, and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Table 7.

Number of Injuries, National Estimates, and Injury Rates by Activity During Injury and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Girls' and Collegiate Women's Soccera

| Surveillance System and Activity During Injury |

Practice |

Competition |

||||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

National Estimates, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2005–2006 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| Attempting a slide tackle | 6 (0.6) | 3881 (0.7) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 13 (0.6) | 8056 (0.7) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05) |

| Ball handling | 98 (9.9) | 53 902 (9.7) | 0.10 (0.08, 0.12) | 236 (11.2) | 137 594 (11.1) | 0.56 (0.49, 0.64) |

| Blocking shot | 17 (1.7) | 8172 (1.5) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 43 (2.0) | 24 506 (2.0) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.13) |

| Chasing loose ball | 70 (7.1) | 40 358 (7.3) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.09) | 290 (13.8) | 181 355 (14.7) | 0.69 (0.61, 0.77) |

| Conditioning | 159 (16.1) | 81 530 (14.7) | 0.16 (0.14, 0.19) | 7 (0.3) | 3320 (0.3) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.03) |

| Defending | 97 (9.8) | 54 892 (9.9) | 0.10 (0.08, 0.12) | 398 (19.0) | 236 939 (19.2) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) |

| General play | 319 (32.2) | 184 982 (33.4) | 0.33 (0.29, 0.36) | 415 (19.8) | 247 288 (20.0) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.09) |

| Goaltending | 59 (6.0) | 31 800 (5.7) | 0.06 (0.05, 0.08) | 170 (8.1) | 82 545 (6.7) | 0.41 (0.35, 0.47) |

| Heading ball | 27 (2.7) | 11 587 (2.1) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 181 (8.6) | 97 569 (7.9) | 0.43 (0.37, 0.50) |

| Passing | 51 (5.2) | 37 064 (6.7) | 0.05 (0.04, 0.07) | 101 (4.8) | 69 060 (5.6) | 0.24 (0.19, 0.29) |

| Receiving a slide tackle | 7 (0.7) | 3963 (0.7) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 36 (1.7) | 32 075 (2.6) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.11) |

| Receiving pass | 25 (2.5) | 11 697 (2.1) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04) | 122 (5.8) | 63 844 (5.2) | 0.29 (0.24, 0.34) |

| Shooting | 55 (5.6) | 30 238 (5.3) | 0.06 (0.04, 0.07) | 88 (4.2) | 52 830 (4.3) | 0.21 (0.17, 0.25) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||||

| Attempting a slide tackle | 23 (0.9) | 355 (0.8) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 69 (2.8) | 1299 (2.8) | 0.37 (0.28, 0.45) |

| Ball handling | 168 (6.7) | 2543 (5.4) | 0.29 (0.24, 0.33) | 215 (8.8) | 3871 (8.3) | 1.14 (0.99, 1.29) |

| Blocking shot | 54 (2.2) | 1266 (2.7) | 0.09 (0.07, 0.12) | 49 (2.0) | 962 (2.0) | 0.26 (0.19, 0.33) |

| Chasing loose ball | 66 (2.6) | 1413 (3.0) | 0.11 (0.09, 0.14) | 178 (7.3) | 3451 (7.4) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.08) |

| Conditioning | 328 (13.1) | 5299 (11.3) | 0.56 (0.50, 0.62) | 12 (0.5) | 144 (0.3) | 0.06 (0.03, 0.10) |

| Defending | 161 (6.4) | 3110 (6.6) | 0.28 (0.23, 0.32) | 388 (15.8) | 7409 (15.9) | 2.05 (1.85, 2.26) |

| General play | 1060 (42.2) | 21 153 (45.1) | 1.82 (1.71, 1.93) | 828 (33.8) | 16 306 (35.0) | 4.38 (4.08, 4.68) |

| Goaltending | 207 (8.2) | 3694 (7.9) | 0.35 (0.31, 0.40) | 158 (6.5) | 3188 (6.8) | 0.84 (0.71, 0.97) |

| Heading ball | 86 (3.4) | 1693 (3.6) | 0.15 (0.12, 0.18) | 245 (10.0) | 4576 (9.8) | 1.30 (1.13, 1.46) |

| Passing | 99 (3.9) | 1768 (3.8) | 0.17 (0.14, 0.20) | 101 (4.1) | 1788 (3.8) | 0.53 (0.43, 0.64) |

| Receiving a slide tackle | 29 (1.2) | 477 (1.0) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.07) | 72 (2.9) | 1324 (2.8) | 0.38 (0.29, 0.47) |

| Receiving pass | 64 (2.6) | 1112 (2.4) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) | 53 (2.2) | 811 (1.7) | 0.28 (0.20, 0.36) |

| Shooting | 167 (6.7) | 3039 (6.5) | 0.29 (0.24, 0.33) | 81 (3.3) | 1474 (3.2) | 0.43 (0.34, 0.52) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Activity excludes 152 injuries reported in HS RIO and 131 injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP because of missing data or athletic trainer reporting Other or Unknown. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 because of rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition, (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional, and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

College.

As with high school, the most frequent mechanisms of injury during practices and competitions were no contact (practices = 38.3%; competitions = 18.0%) and contact with another person (practices = 19.0%; competitions = 53.6%; Table 6). The most common activity during injury in practices and competitions was general play (practices = 42.2%; competitions = 33.8%; Table 7). In competitions, 15.8% of injuries also occurred during defending.

Position-Specific Injuries in Competitions

During competitions at the high school level, concussion was the most often cited injury among defenders, goalkeepers, and midfielders (25.6%, 36.8%, and 24.4%, respectively), with most being due to contact with another person (Table 8). Ankle sprain was the most frequent injury among high school forwards (19.8%). During competitions at the collegiate level, ankle sprain was the most common injury among defenders, forwards, and midfielders (16.9%, 19.4%, and 22.7%, respectively), typically due to contact with another person. Concussion was the most frequent injury during competitions among collegiate goalkeepers (22.4%).

Table 8.

Most Common Injuries Associated With Position in Competitions in High School and Collegiate Women's Soccera

| Position |

HS RIO (2005–2006 Through 2013–2014) |

NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 Through 2013–2014) |

||||

| Most Common Injuries |

Injuries Within Position, % |

Most Frequent Mechanism of Injury for This Injury Within Position |

Most Common Injuries |

Injuries Within Position, % |

Most Frequent Mechanism of Injury for This Injury Within Position |

|

| Defense | Concussion | 25.6 | Contact with another person | Ankle sprain | 16.9 | Contact with another person |

| Ankle sprain | 18.2 | Contact with another person | Concussion | 12.8 | Contact with another person | |

| Forward | Ankle sprain | 19.8 | Contact with another person | Ankle sprain | 19.4 | Contact with another person |

| Concussion | 18.5 | Contact with another person | Concussion | 13.4 | Contact with another person | |

| Knee sprain | 13.8 | Contact with another person | Hip/thigh/upper leg strain | 10.0 | No contact | |

| Goalkeeper | Concussion | 36.8 | Contact with another person | Concussion | 22.4 | Contact with another person |

| Midfielder | Concussion | 24.4 | Contact with another person | Ankle sprain | 22.7 | Contact with another person |

| Ankle sprain | 20.4 | Contact with another person | Concussion | 15.5 | Contact with another person | |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excludes 115 competition injuries reported in HS RIO and 120 competition injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP because of position not being indicated. The table reads as follows: for the defense position in high school, concussions composed 25.6% of all competition injuries to that position. The most common mechanism of injury for this specific injury for this specific position was contact with another person. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition, (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional, and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to specifically compare time-loss injury data between high school girls' and collegiate women's soccer players. This information is critical given the recent growth in soccer nationally and efforts to reduce injuries, especially concussions and knee sprains.1,2 Injury rates for girls' and women's soccer were lower than those previously reported6,18 but still demonstrate areas for injury prevention. Female soccer athletes were at greater risk of sustaining a time-loss injury during competitions versus practices at both the high school and collegiate levels. Despite a greater absolute number of injuries in high school girls' soccer (likely because of the greater number of athletes), the rate of injury was higher in collegiate women's soccer. The majority of injuries affected the lower extremity and, at the collegiate level, occurred during the preseason. Of particular significance, concussions accounted for a higher proportion of injuries at the high school level than at the collegiate level and for more than one-third of injuries to high school goalkeepers during competitions. These findings highlight the continued need for injury surveillance in female soccer at both the high school and collegiate levels, focused efforts to disseminate and implement evidence-based injury-prevention strategies in girls' soccer, and areas for consideration of rule changes and training recommendations to ensure the long-term health and safety of these athletes.

Comparisons With Previous Research

The injury rates reported in our study for the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years were lower than those reported more than 20 years earlier.6 Compared with our competition and practice rates of 13.13 and 4.48/1000 AEs, respectively, rates from the NCAA-ISP 20 years prior (1988–1989 through 2002–2003 academic years) were 16.44 and 5.23/1000 AEs, respectively. These findings may suggest that recent advances in injury prevention, training, and injury management may be stabilizing overall injury rates in women's soccer. In particular, these advances may also have aided in minimizing the severity of injury in the sport, which may help to explain the large proportion of injuries resulting in time loss of less than 1 week (range, 37.7%–59.2%). However, because of variations in data-collection methods among our current study and previous research, caution must be taken in interpreting changes in reported injury rates. Nevertheless, strides have been made in preventing lower extremity noncontact injuries (such as muscle strains and ligament sprains7,19–22), managing concussions, and advancing training-load monitoring for reducing overuse injuries. Yet because of the negative long-term consequences associated with sport-related injury, including future inactivity23 and osteoarthritis,24,25 we must continue developing and evaluating injury-prevention programming targeted at female soccer players. In addition, we advocate for more examinations of the direct effects of the use and implementation of such interventions.

Comparisons Between and Within High School and Collegiate Soccer

Despite a greater number of estimated injuries in high school girls' soccer compared with collegiate women's soccer due to a larger number of high school athletes, the injury rate was higher in the latter than the former. These differences in injury rates between competition levels were consistent across injury mechanisms, suggesting that no particular mechanism was likely responsible for the discrepancies observed. However, multiple explanations are possible for these differences in injury rates, including an overall higher level of intensity, skill, and size of players at the collegiate level compared with high school soccer. For example, stronger, taller athletes with greater body mass are capable of generating higher forces and greater speeds. These factors may affect both contact and noncontact injuries. Another primary risk factor for many noncontact lower extremity injuries is a history of a previous lower extremity injury.26–28 Consequently, the higher incidence of noncontact injury observed in collegiate soccer may be a result of players participating with a history of injury that occurred during high school sport,29 which emphasizes the need for continued attention to previous injuries even after initial recovery.

Lower injury rates at the high school level may also be influenced by the underreporting of minor injuries due to irregular access to an AT. Athletic trainers are integral members of a sports organization, working to prevent, identify, acutely treat, and assess athletes' injuries. Most collegiate women's soccer teams have immediate access to ATs, which may have resulted in the larger number of minor injuries that required less than 1 week of time loss. It is estimated that only 70% of high schools in the United States have at least 1 AT on site and only 55% of all high school student-athletes have access to care from a high school AT.30 Even though all high schools in this study provided at least some access to an AT as part of the inclusion criteria of the HS RIO surveillance system, many high school ATs balance coverage for women's soccer among other sports, which may consequently impair regular reporting.

Interestingly, soccer athletes from smaller high schools had a higher injury rate than their peers from larger high schools. This discrepancy may be due to differences in resources, such as coaching and medical staff, or to the possibility that some athletes in smaller schools may have less experience with soccer. Athletes at smaller schools may be more likely to participate in multiple sports and, therefore, be able to make the soccer team because of less competition. Yet they may then compete against larger schools that have fielded more competitive teams with players who have more experience in the sport. Differences in injury rates among the 3 divisions of collegiate women's soccer were also observed. However, the differences were not consistent across divisions, with the rate being lowest in Division II. The findings highlight how injury incidence may be associated with school-related characteristics, such as the size or division level. Future researchers should evaluate these observations to help target the most effective injury-prevention methods for high schools and NCAA member institutions, which have varying characteristics and available resources.

Event Type

At both the high school and collegiate levels, competition injury rates were consistently higher than practice injury rates, as seen in previous literature.6,18 Overall, high school soccer practices appeared to have a relatively lower risk of injury compared with collegiate soccer practices, which may be the result of varying levels of intensity or training volume. Despite a lower risk of injury during practices, collegiate practices still resulted in a larger absolute number of injuries among soccer athletes. The collegiate season is typically longer than the high school season, with fewer days off provided to these athletes. The collegiate season often includes an intense nontraditional season as well, although these data were not available for the current analysis. Many collegiate players also participate in summer leagues, resulting in negligible time away from soccer. Furthermore, significant disparities were noted among times of year for collegiate soccer, with the greatest risk occurring in the preseason, followed by the regular season. Attention to acute : chronic workloads, especially when athletes return to competitive training, may be of particular importance in women's collegiate soccer. At both levels of soccer, player-to-player contact may also contribute to the higher risk of head/neck injuries, including concussions, during competitions. Injury-prevention and rule-modification strategies may provide additional opportunities to reduce injury incidence. These include the enforcement of rules that target both competitions and practices and protect soccer players during player-to-player contact.31

Common Injuries and Injury Prevention

Lower extremity injuries composed the majority of all injuries sustained in both collegiate women's and high school girls' soccer, which is supported by previous literature.6,32 The most common injury locations were consistent across the high school and collegiate levels of play: the knee and ankle during both practices and competitions, the head/face during competitions, and the hip/thigh/upper leg during practices.

Lower Extremity Strains and Sprains.

Muscle/tendon strains, especially to the hip/thigh/upper leg, continued to be frequent injuries in soccer.33 Muscle strength appears to have a role in preventing muscle/tendon strains, especially hamstrings strains. Multiple authors7,8 have demonstrated the importance of eccentric strength and training, such as the Nordic hamstrings exercise, in reducing the risk of hamstrings muscle strains in soccer athletes. Hip adduction : abduction strength ratios have been shown to predict adductor strains in ice hockey athletes,34 but whether this is true for soccer athletes is unknown. Recent advances in technology that improve the ability to monitor training loads and physiological effects have the potential to mitigate the risk of these frequent fatigue-related injuries. Based on the available evidence, clinicians should perform a comprehensive evaluation of all lower extremity muscle strains and follow them as the athletes rehabilitate and return to functional training, in order to appropriately manage the individual factors that may be contributing to future injury risks.

In conjunction with muscle/tendon strains, ankle- and knee-ligament sprains composed more than 50% of practice injuries in both high school and collegiate soccer. In general, ligament injuries accounted for the highest rate of competition injuries at both levels. These rates and percentages emphasize the need for effective ankle- and knee-injury prevention. Strong evidence9,19,35,36 indicated that among female soccer players, noncontact lower extremity injuries, such as muscle strains and ligament sprains, can be prevented. Noncontact mechanisms are responsible for the highest practice-related injury rates, regardless of age level, and the highest competition-related injury rates in collegiate soccer. Most of the injury-prevention literature has addressed integrated, or multifaceted, training programs that involve multiple types of exercises, including balance, plyometric, flexibility, agility, and resistance. Proper instruction in and feedback on movement quality are also emphasized during all exercises. Specifically, these types of programs that are used as a 15- to 20-minute team warm-up can reduce anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in high school girls' soccer by 60% to 80%.9–11 Gilchrist et al19 reported significant reductions in practice and competition ACL injuries after NCAA Division I teams performed an injury-prevention program. These studies demonstrated the effectiveness of preventive training programs among women's soccer athletes specifically. However, despite this evidence, current research indicates that widespread injury-prevention implementation is not taking place37,38 and that ACL reconstructions are actually increasing among adolescent females.39 Because of data limitations, we did not present estimates of ACL injuries from this dataset, as they would have been incomplete. Nevertheless, more recent, in-depth data can be assessed in accordance with the use of such prevention programming to gauge whether injury incidence is reduced. Moreover, future investigators need to discover ways to overcome barriers to widespread preventive training program adoption throughout girls' and women's soccer programs.

Head and Face Injuries.

Concussions were one of the most common injuries during both high school and collegiate soccer competitions, although this may have been related to improved detection and reporting.40,41 Concussions were frequent among all positions, accounting for a particularly high proportion of competition injuries in high school goalkeepers (37%). Player contact was the most often cited mechanism of concussions across positions. This finding highlights the need to teach proper techniques for game play in which player contact may occur, such as heading the ball or slide tackling. There may also be a role for neck strengthening in terms of force dissipation during head contact.42 Advocates have focused on the role of heading in concussion during soccer. However, it is important to understand that player-to-player contact was the primary mechanism underlying concussion when heading the ball.31 This remains an important area of soccer research that has received insufficient attention to date.

In addition, anticipation may have an important function in preventing soccer injuries, especially heading-related injuries. The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) 11+ injury-prevention program incorporates an exercise that includes a perturbation from an opponent that mimics collisions during running or heading. This type of training might specifically protect against head or face injuries and may also help to prevent other injuries resulting from the common activities of defending or receiving a pass. High school athletes have a greater likelihood of sustaining a serious injury as a result of contact with an opponent. Therefore, this type of peer-perturbation training might be especially critical for high school athletes, in addition to rule changes that may need to be considered.

LIMITATIONS

Our findings may not be generalizable to other playing levels, such as youth, middle school, and professional programs, or to collegiate programs at non-NCAA institutions or high schools without National Athletic Trainers' Association–affiliated ATs. Furthermore, we were unable to account for factors potentially associated with injury occurrence, such as AT coverage, implemented injury-prevention programs, and athlete-specific characteristics (eg, previous injury, functional capabilities). Also, although HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP are similar injury-surveillance systems, it is important to consider the variations that do exist between the systems; this is most evident in HS RIO's use of a random sample and the NCAA-ISP's use of a convenience sample. In addition, differences may exist between high school and college in regard to the length of the season in total, as well as the preseason, regular season, and postseason; the potentially longer collegiate season may increase the injury risk. We calculated injury rates using AEs, which may not be as precise an at-risk exposure measure as minutes, hours, or total number of game plays across a season. However, collecting such exposure data is more laborious than collecting AE data and may be too burdensome for ATs collecting data for HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP.

Although our study is one of few to examine injury incidence across multiple levels of play (eg, high school versus college and competitions versus practices), we were unable to examine differences between starters and nonstarters during competitions; analyses that group both types of players may confound and thus weaken the possible exposure-outcome association for some known injury risk factors. Differences may also exist among the freshman, junior varsity, and varsity teams due to differences in maturation status. Playing positions may vary in physical demands and resulting injury risk. Athlete-exposures were not collected by position, preventing the calculation of position-specific injury rates.

CONCLUSIONS

Although many similarities in injury patterns exist between high school and collegiate female soccer players, injury rates were higher at the collegiate level than at the high school level. Injury rates were also higher during competitions than during practices, although the majority of injuries to collegiate soccer players occurred during practices. These differences may be attributable to differences in reporting, activity intensity, and game-play skill. More importantly, the findings highlight the need for continued efforts toward injury prevention, with a specific focus on noncontact injuries and concussions. Growing evidence demonstrates that the majority of noncontact lower extremity injuries can be reduced with neuromuscular preventive training programs, but whether their adoption is widespread is unknown and injury rates remain high in female soccer players across age levels. Further research is needed to evaluate the effects of training load and recovery methods on injuries, especially during the collegiate soccer preseason and in high school athletes who specialize in soccer. Although overall injury rates have decreased from 20 years ago, more ACL reconstructions are being performed at younger ages, especially in adolescent females.39 Continued sport-related injury-surveillance data are required to drive the development, refinement, and maintenance of targeted injury-prevention interventions in girls' and women's soccer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The NCAA-ISP data were provided by the Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention. The ISP was funded by the NCAA. Funding for HS RIO was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants R49/CE000674-01 and R49/CE001172-01 and the National Center for Research Resources award KL2 RR025754. We also acknowledge the research funding contributions of the National Federation of State High School Associations (Indianapolis, IN), National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (Overland Park, KS), DonJoy Orthotics (Vista, CA), and EyeBlack (Potomac, MD). The content of this report is solely our responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations. We thank the many ATs who have volunteered their time and efforts to submit data to HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP. Their efforts are greatly appreciated and have had a tremendously positive effect on the safety of high school and collegiate student-athletes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Participation statistics (2016) National Federation of State High Schools Web site. 2018 http://www.nfhs.org/ParticipationStatics/ParticipationStatics.aspx/ Accessed February 27.

- 2.Student-athlete participation: 1981–82—2014–15. National Collegiate Athletic Association Web site. 2018 http://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/Participation%20Rates%20Final.pdf Accessed February 27.

- 3.Kerr ZY, Dompier TP, Snook EM, et al. National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System: review of methods for 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 data collection. J Athl Train. 2014;49(4):552–560. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sports-related injuries among high school athletes—United States, 2005–06 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(38):1037–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries: a review of concepts. Sports Med. 1992;14(2):82–99. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dick R, Putukian M, Agel J, Evans TA, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's soccer injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2002–2003. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):278–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Attar WSA, Soomro N, Sinclair PJ, Pappas E, Sanders RH. Effect of injury prevention programs that include the Nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injury rates in soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(5):907–916. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0638-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goode AP, Reiman MP, Harris L, et al. Eccentric training for prevention of hamstring injuries may depend on intervention compliance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(6):349–356. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaBella CR, Huxford MR, Grissom J, Kim KY, Peng J, Christoffel KK. Effect of neuromuscular warm-up on injuries in female soccer and basketball athletes in urban public high schools: cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(11):1033–1040. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandelbaum BR, Silvers HJ, Watanabe DS, et al. Effectiveness of a neuromuscular and proprioceptive training program in preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(7):1003–1010. doi: 10.1177/0363546504272261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walden M, Atroshi I, Magnusson H, Wagner P, Hagglund M. Prevention of acute knee injuries in adolescent female football players: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e3042. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreck C. States Address concerns about concussions in youth sports. Education Commission of the States Web site. 2018 https://www.ecs.org/states-address-concerns-about-concussions-in-youth-sports/ Accessed February 27.

- 13.2014–15 NCAA Sports Medicine Handbook. National Collegiate Athletic Association Web site. 2018 http://www.ncaapublications.com/DownloadPublication.aspx?download=MD15.pdf Published August 2014. Accessed February 27.

- 14.Kerr ZY, Comstock RD, Dompier TP, Marshall SW. The first decade of web-based sports injury surveillance (2004–2005 through 2013–2014): methods of the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program and High School Reporting Information Online. J Athl Train. 2018;53(8):729–737. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-143-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rechel JA, Yard EE, Comstock RD. An epidemiologic comparison of high school sports injuries sustained in practice and competition. J Athl Train. 2008;43(2):197–204. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Census regions of the United States. US Census Bureau Web site. 2018 http://www.census.gov/const/regionmap.pdf Accessed February 27.

- 17.Kucera KL, Marshall SW, Bell DR, DiStefano MJ, Goerger CP, Oyama S. Validity of soccer injury data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Injury Surveillance System. J Athl Train. 2011;46(5):489–499. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell JW, Barber-Foss KD. Injury patterns in selected high school sports: a review of the 1995–1997 seasons. J Athl Train. 1999;34(3):277–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilchrist J, Mandelbaum BR, Melancon H, et al. A randomized controlled trial to prevent noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury in female collegiate soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1476–1483. doi: 10.1177/0363546508318188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grooms DR, Palmer T, Onate JA, Myer GD, Grindstaff T. Soccer-specific warm-up and lower extremity injury rates in collegiate male soccer players. J Athl Train. 2013;48(6):782–789. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGuine TA, Keene JS. The effect of a balance training program on the risk of ankle sprains in high school athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(7):1103–1111. doi: 10.1177/0363546505284191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silvers-Granelli H, Mandelbaum B, Adeniji O, et al. Efficacy of the FIFA 11+ Injury Prevention Program in the collegiate male soccer player. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(11):2628–2637. doi: 10.1177/0363546515602009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hootman JM, Macera CA, Ainsworth BE, Addy CL, Martin M, Blair SN. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries among sedentary and physically active adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(5):838–844. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luc B, Gribble PA, Pietrosimone BG. Osteoarthritis prevalence following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and numbers-needed-to-treat analysis. J Athl Train. 2014;49(6):806–819. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lohmander LS, Ostenberg A, Englund M, Roos H. High prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, pain, and functional limitations in female soccer players twelve years after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(10):3145–3152. doi: 10.1002/art.20589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shelbourne KD, Gray T, Haro M. Incidence of subsequent injury to either knee within 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(2):246–251. doi: 10.1177/0363546508325665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paterno MV, Rauh MJ, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Incidence of contralateral and ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury after primary ACL reconstruction and return to sport. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22(2):116–121. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318246ef9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faude O, Junge A, Kindermann W, Dvorak J. Risk factors for injuries in elite female soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(9):785–790. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.027540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reeser JC, Gregory A, Berg RL, Comstock RD. A comparison of women's collegiate and girls' high school volleyball injury data collected prospectively over a 4-year period. Sports Health. 2015;7(6):504–510. doi: 10.1177/1941738115600143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pryor RR, Casa DJ, Vandermark LW, et al. Athletic training services in public secondary schools: a benchmark study. J Athl Train. 2015;50(2):156–162. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.2.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Comstock RD, Currie DW, Pierpoint LA, Grubenhoff JA, Fields SK. An evidence-based discussion of heading the ball and concussions in high school soccer. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):830–837. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson L, Junge A, Chomiak J, Graf-Baumann T, Dvorak J. Incidence of football injuries and complaints in different age groups and skill-level groups. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(suppl 5):S51–S57. doi: 10.1177/28.suppl_5.s-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hickey J, Shield AJ, Williams MD, Opar DA. The financial cost of hamstring strain injuries in the Australian Football League. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(8):729–730. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Campbell RJ, McHugh MP. The association of hip strength and flexibility with the incidence of adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):124–128. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugimoto D, Myer GD, McKeon JM, Hewett TE. Evaluation of the effectiveness of neuromuscular training to reduce anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: a critical review of relative risk reduction and numbers-needed-to-treat analyses. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(14):979–988. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugimoto D, Myer GD, Bush HM, Klugman MF, Medina McKeon JM, Hewett TE. Compliance with neuromuscular training and anterior cruciate ligament injury risk reduction in female athletes: a meta-analysis. J Athl Train. 2012;47(6):714–723. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.6.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joy EA, Taylor JR, Novak MA, Chen M, Fink BP, Porucznik CA. Factors influencing the implementation of anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention strategies by girls soccer coaches. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(8):2263–2269. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31827ef12e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norcross MF, Johnson ST, Bovbjerg VE, Koester MC, Hoffman MA. Factors influencing high school coaches' adoption of injury prevention programs. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(4):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herzog MM, Marshall SW, Lund JL, Pate V, Mack CD, Spang JT. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction among adolescent females in the United States, 2002 through 2014. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):808–810. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuckerman SL, Kerr ZY, Yengo-Kahn A, Wasserman E, Covassin T, Solomon GS. Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in NCAA athletes from 2009–2010 to 2013–2014: incidence, recurrence, and mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(11):2654–2662. doi: 10.1177/0363546515599634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenthal JA, Foraker RE, Collins CL, Comstock RD. National high school athlete concussion rates from 2005–2006 to 2011–2012. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1710–1715. doi: 10.1177/0363546514530091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins CL, Fletcher EN, Fields SK, et al. Neck strength: a protective factor reducing risk for concussion in high school sports. J Prim Prev. 2014;35(5):309–319. doi: 10.1007/s10935-014-0355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]