Abstract

Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) monitors ER-luminal Ca2+ levels to maintain cellular Ca2+ balance and to support Ca2+ signalling. The prevailing view has been that STIM1 senses reduced ER Ca2+ through dissociation of bound Ca2+ from a single EF-hand site, which triggers a dramatic loss of secondary structure and dimerization of the STIM1 luminal domain. Here we find that the STIM1 luminal domain has 5–6 Ca2+-binding sites, that binding at these sites is energetically coupled to binding at the EF-hand site, and that Ca2+ dissociation controls a switch to a second structured conformation of the luminal domain rather than protein unfolding. Importantly, the other luminal-domain Ca2+-binding sites interact with the EF-hand site to control physiological activation of STIM1 in cells. These findings fundamentally revise our understanding of physiological Ca2+ sensing by STIM1, and highlight molecular mechanisms that govern the Ca2+ threshold for activation and the steep Ca2+ concentration dependence.

Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) monitors ER-luminal Ca2+ levels to maintain cellular Ca2+ balance. Here the authors find that the STIM1 luminal domain monomer has multiple Ca2+ - binding sites which set the threshold for physiological activation of STIM1 in cells.

Introduction

Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), an ER-membrane protein, is a pivotal regulator of cellular Ca2+ balance and Ca2+ signalling. Each STIM1 monomer consists of an ER-luminal domain specialized for Ca2+ sensing in the range ~100–400 μM, a single transmembrane helix, and a cytoplasmic domain capable of regulated interaction with plasma membrane ORAI Ca2+ channels at ER-plasma membrane contacts (Fig. 1a)1–3.

Fig. 1.

EFSAM-GrpE design and Ca2+ responsiveness. a Cartoon of activated STIM1 (58-473) as inferred from the literature45. Domain organization is marked. Residues 24–57 and 473–685 are not depicted. b Cartoon of the expected EFSAM-GrpE structure used in the current study, showing structural similarity to the extended activated STIM1. Green ovals represent EFSAM (58-209) and blue cartoon denotes Thermus thermophilus GrpE. GrpE is not structurally related to STIM1 except for the presence of extended α-helices that form a coiled coil. The coiled coil is constitutive in GrpE, unlike in STIM1. c Schematic of the EFSAM-GrpE construct design. d Size exclusion chromatography of the Ca2+-bound (20 mM Ca2+; blue line) and Ca2+-free (5 mM EGTA; red line) forms of EFSAM-GrpE. e Schematic of chemical labelling of EFSAM-GrpE, depicting the case where individual monomers are labelled with fluorescein and AF594. Other possible combinations in the random labelling approach used here are not illustrated. f Fluorescence emission spectra (λex = 420 nm) of single-cysteine EFSAM-GrpE labelled with fluorescein (Donor alone), AF594 (Acceptor alone) or with both dyes (Donor and Acceptor). All measurements were made in Ca2+-free buffer. g Fluorescence spectral scans (λex = 420 nm) of double-labelled EFSAM-GrpE with varying amounts of Ca2+

Early mechanistic investigations into how STIM1 controls Ca2+ signalling focused on the single predicted EF-hand in the STIM1 luminal domain. Mutations that compromised Ca2+ binding to the EF-hand led to constitutive STIM1 activation, evidenced by the relocalization of STIM1 to ER-plasma membrane junctions in resting cells and by constitutive Ca2+ influx4–7. An NMR structure of the luminal region STIM1(58-201) with Ca2+ bound revealed a compact domain consisting of paired EF-hands—one canonical, the second noncanonical and unable to bind Ca2+— closely interacting with a sterile α motif (SAM) domain8. STIM1(58-201) is termed the ‘EFSAM’ domain on this basis. Two other elements with clearly defined functions, both located in the STIM1 cytoplasmic region, are the STIM1 ORAI activating region (SOAR; residues 344-442) or CRAC activation domain (CAD; residues 342-448) that interacts with and gates the ORAI channel9–12; and the C-terminal polybasic tail (residues 671-685) that targets active STIM1 to ER-plasma membrane junctions9,11,13,14.

The STIM1 cytoplasmic domain undergoes an inactive > active transition in which availability of the SOAR/CAD domain and the polybasic tail is regulated by the level of free Ca2+ in ER stores. Inactive STIM1 in cells is a dimer held together by SOAR/CAD–SOAR/CAD interactions15–19. The SOAR/CAD domain is folded back against CC1 in a way that precludes its effective interaction with plasma membrane ORAI channels19,20. STIM1 activation is triggered when Ca2+ dissociates from STIM1 ER-luminal domains, the EFSAM domains rearrange or dimerize, and the STIM1 cytoplasmic domains undergo a conformational change that releases the SOAR/CAD domains and the polybasic tails8,19,21–27. Biochemical and biophysical studies have established that STIM communicates the store-depletion signal to the cytoplasm via STIM–STIM association in the transmembrane and predicted coiled coil 1 (CC1) regions19,26–28. These intradimer interactions stabilize a coiled coil and bury the CC1 surface that would otherwise retain SOAR/CAD near the ER in resting cells. Active STIM1 relocalizes to ER-plasma membrane junctions, and its extended cytoplasmic domain bridges the ~ 15 nm ER-plasma membrane distance, and recruits and gates ORAI channels3.

The accepted description of how STIM1 senses reduced ER Ca2+ has come from studies of the isolated recombinant STIM1 luminal domain. The triggering event has been thought to be Ca2+ dissociation from canonical EF-hand sites, leading in turn to a major loss of EFSAM secondary structure and dimerization of EFSAM domains8,21,22, and apposition of TM-CC1 regions19,26–28. Here we find that Ca2+ sensing entails loss of Ca2+ from both the EF-hand and other sites in EFSAM; that the additional binding sites interact with the EF-hand site to set the Ca2+ sensitivity of STIM1; and that luminal domain unfolding is not a prerequisite for the EFSAM-EFSAM dimerization that drives STIM1 activation.

Results

A soluble STIM1 construct for study of Ca2+ binding

The EFSAM domain of STIM1 has been studied previously as an isolated domain to parse the STIM1 Ca2+ response. In cells, the EFSAM domain is linked via the STIM1 transmembrane helix and CC1 region to dimeric SOAR/CAD, in both the STIM1 inactive and active conformations (Fig. 1a). We reasoned that the EFSAM conformational transitions that take place upon Ca2+ binding and dissociation might be replicated more faithfully in experiments where EFSAM was similarly linked to a dimeric protein than in experiments with isolated EFSAM. Therefore, we undertook to design a fully soluble protein, omitting the transmembrane segment, and incorporating a stably dimerizing C-terminal domain. This more natural linkage might incidentally reduce the nonphysiological aggregate formation characteristic of the isolated EFSAM domain at low concentrations of Ca2+. After trials with candidate dimers of known and stable structure, we settled on an EFSAM protein coupled through a short linker to Thermus thermophilus GrpE (Fig. 1b, c). EFSAM-GrpE was soluble when expressed in bacteria, unlike the isolated EFSAM domain, which needed to be purified under denaturing conditions and refolded21,24. EFSAM-GrpE showed no change in migration on size-exclusion chromatography in the presence or absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 1d), and, importantly for the intended use, the purified protein did not aggregate in the absence of Ca2+.

Ca2+-dependent conformational change in EFSAM-GrpE

A characteristic early indicator of Ca2+ dissociation from the STIM1 luminal domain in cells is STIM–STIM FRET between N-terminal fluorescent protein labels. We designed a FRET experiment to test for similar sensing of Ca2+ by EFSAM-GrpE in vitro. EFSAM-GrpE dimers were randomly labelled with fluorescein and Alexa Fluor 594 at an engineered N-terminal cysteine in the EFSAM domain (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 1a). As with CFP/YFP labels in cells, an appreciable fraction of EFSAM-GrpE dimers will contain donor–donor or acceptor–acceptor pairs, and with chemical labelling some sites will remain unlabelled, so in the best case only half of the dimers can exhibit intradimer FRET. Samples rigorously depleted of Ca2+ by passage over Chelex resin exhibited FRET (Fig. 1f), indicating close apposition of the labels in the two EFSAM domains. The observed FRET was between labels in the same EFSAM-GrpE dimer, since a mixture of comparable amounts of singly donor-labelled and acceptor-labelled proteins exhibited no FRET (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Further, FRET was reduced as increasing concentrations of Ca2+ were added (Fig. 1g), showing that in vitro, as in cells9,16,29, Ca2+ causes a relative movement of the EFSAM domains.

To verify that the change in FRET upon Ca2+ addition was not an isolated finding that reflected the particular EFSAM fusion construct used, we replicated the experiment with EFSAM-SAH-GrpE, a construct in which EFSAM was connected to GrpE by a monomeric single α-helix linker the length of CC1 (Supplementary Fig. 1c–h). The results were similar, with this longer construct also showing substantial FRET in the absence of Ca2+, and reduced FRET in the presence of Ca2+. Thus EFSAM-GrpE replicates a defining aspect of the Ca2+-dependent STIM1 conformational change.

Notably, in both cases, the midpoint of the transition to lower FRET falls at ~1–10 μM Ca2+, suggesting that at least one Ca2+ is bound to EFSAM with Kd below ~ 10 μM. This value differs from the Kd of a STIM1 EF-hand grafted into CD2 domain 1 (~500 μM; ref. 30). The most plausible explanation is that Ca2+ binding to the EF-hand in the full EFSAM domain is stabilized allosterically by the interaction of the EF-hand portion with the SAM domain, much as Ca2+ binding to calmodulin can be stabilized by interaction with target proteins or peptides31–33. The value measured in the EFSAM-GrpE FRET assay also differs from the measured IC50 for inhibition by Ca2+ of STIM1 activation in cells ( ~ 200 μM; refs. 34,35) and from that determined in our Ca2+ titration of STIM1(A230C) crosslinking28. The higher IC50 characteristic of full-length STIM1 is most likely to reflect an energetic cost exacted by the coupling between Ca2+ binding to the STIM1 EFSAM domain and the concerted conformational change of full-length STIM1 from the active to the inactive form.

The key experiments defining STIM1 function in cells, including the observation of STIM–STIM FRET upon Ca2+ store depletion9 and measurement of the Ca2+ concentration dependence of STIM activation34,35, were conducted at room temperature. We have carried out this initial FRET experiment and other experiments in this paper under comparable conditions. In a series of parallel experiments, we have seen no qualitative difference in STIM1 relocalization in cells responding to store depletion at room temperature and at 37 C.

Ca2+-dependent conformational change in cells

It has been unclear how much of the increase in STIM1-STIM1 FRET during store depletion is due to EFSAM–EFSAM rearrangement and how much may arise from SOAR/CAD oligomerization (see discussion in ref. 3). To examine the contribution of EFSAM rearrangements to STIM–STIM FRET in cells, we engineered EFSAM-TM-CC1-GrpE constructs extending to residue 343 of CC1, fused to GrpE in place of SOAR/CAD, and labelled at the N terminus with either CFP or YFP (Fig. 2a–d). HeLa cells coexpressing the CFP- and YFP-labelled proteins exhibited a FRET increase upon store depletion with thapsigargin (TG) that was comparable in magnitude to that of cells expressing CFP- and YFP-labelled full-length STIM1 (Fig. 2a, b, d). A tandem CFP-YFP fusion protein expressed as a control exhibited higher FRET, presumably reflecting the higher fraction of donor–acceptor dimers, but, as expected, showed no response to store depletion (Fig. 2c, d). As there is no evidence from our in vitro gel filtration experiments for higher-order oligomerization of EFSAM-GrpE (Fig. 1d), the results suggest that intradimer rearrangement of EFSAM domains accounts for an appreciable part of the STIM1–STIM1 FRET change in cells.

Fig. 2.

Ca2+-dependent conformational change in cells. a–b Confocal micrographs showing FRET before (resting; upper panels) and after 1 μM TG stimulation (activated; lower panels) in representative HeLa cells co-expressing CFP- and YFP-tagged full-length STIM1 (a; n = 7) or EFSAM-TC-GrpE (b; TC = STIM1 transmembrane and CC1 regions; n = 7). Scale bars, 5 μm. False-color scale representing normalized FRET efficiency, expNFRET, for each image is included as inset. c Confocal micrograph showing FRET in HeLa cells expressing a CFP-YFP tandem construct as a control, without TG treatment (n = 5). Scale bar, 5 μM. False-color scale representing normalized FRET efficiency, expNFRET, is included as inset. d Quantification of FRET changes in a–c. Error bars report SEM. CFP-YFP FRET change in HeLa cells expressing either STIM1 or EFSAM-TC-GrpE was significant after treatment with 1 μM TG (marked with ***, p < 0.05 by an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test)

Isothermal titration calorimetry detects multiple Ca2+ sites

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measures the heat released or absorbed in a chemical reaction following sequential injections of one of the reactants, and thus permits quantitative studies of ligand binding. To assess Ca2+ binding to EFSAM-GrpE over the range of physiological ER-luminal Ca2+ concentrations, we titrated Ca2+ into an initially Ca2+-free EFSAM-GrpE sample, with a corresponding titration into initially Ca2+-free GrpE serving as control (Fig. 3a, b). The plot of heat released in the EFSAM-GrpE titration leads to three immediate conclusions. First, from the range of molar ratios of Ca2+:protein in which heat release is observed, there are ~5 Ca2+-binding sites per EFSAM monomer (see discussion in Methods). Second, the sites are Ca2+-specific, since similar Ca2+ binding is observed in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ (Supplementary Fig. 2). Third, considering the amounts of Ca2+ added in the titration, the sites in wild-type EFSAM are occupied at concentrations of free Ca2+ below 1 mM (Fig. 3a, legend). It is also evident that the titration is biphasic. In light of the FRET data reported above (Fig. 1g), it is likely that net heat release early in the Ca2+ titration is the sum of an exothermic Ca2+ binding component and an endothermic EFSAM conformational change component. The latter interpretation is backed by ITC measurements, below, on the EFSAM-2NQ mutant, which does not undergo a conformational change and which exhibits a monophasic exothermic binding reaction. These qualitative conclusions are independent of any specific model that might be used to derive binding parameters from the calorimetry data (see discussion in Methods).

Fig. 3.

Multiple Ca2+-binding sites in EFSAM. a–c Isothermal titration calorimetric (ITC) analyses of EFSAM-GrpE WT (a), GrpE (b), and EFSAM-GrpE D76A (c). Left panels, Heat changes measured by injecting 1 μl aliquots of 13 mM Ca2+ into a sample cell containing initially 130 μM protein, stated as the monomer concentration. Right panels, Integrated binding isotherm as a function of molar ratio (Ca2+: protein) after subtracting heats of dilution. In a, the indicated total Ca2+ at 40 min is the amount added to the ITC cell up to that point, corrected for the increase in volume, and free Ca2+ is calculated as total Ca2+ minus bound Ca2+ assuming five sites are occupied in EFSAM. d D4 sensor Ca2+ competition assay design. e–g D4 sensor normalized fluorescence signals in the presence of GrpE (35 μM) (e), EFSAM(D76A)-GrpE (35 μM) (f), or WT EFSAM-GrpE (35 μM) (g) are compared to the Ca2+-binding curve of D4 alone (black solid trace in each panel). h Method used for calculating free Ca2+ and Ca2+ bound to EFSAM (as total Ca2+ minus free Ca2+) from the competition data in g. i Plot of Ca2+ bound to WT EFSAM as a function of free Ca2+ concentration, calculated as in h. Data from two experiments plotted individually

An EF-hand mutation might have been expected to result in the loss of one Ca2+-binding site per monomer, but in fact EFSAM(D76A)-GrpE exhibited no Ca2+ binding detectable by ITC (Fig. 3c). This result indicates that Ca2+ binding at the EF-hand is a prerequisite for Ca2+ binding at the other sites detected in wild-type EFSAM. A corollary is that previous experiments in which the D76A replacement and other replacements in the EF-hand led to loss of the STIM1 Ca2+ response4–7 do not exclude physiologically relevant Ca2+ binding at additional sites.

In simpler cases, ITC data can be analyzed to parse ligand binding to individual sites. Here, given the interdependence of binding at the EF-hand and the other Ca2+-binding sites, the coupling of Ca2+ binding to a change in intradimer EFSAM–EFSAM interactions, and the large number of parameters that would be required for a realistic description of binding, this more detailed analysis is not feasible. However, we have been successful in determining the concentration range in which Ca2+ binds to EFSAM with two alternative approaches described below, a competitive binding assay presented in the next section and a fluorescence enhancement assay using the environment-sensitive dye 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid (ANS).

A fluorescence assay confirms multiple Ca2+ sites in EFSAM

We sought to confirm the existence of multiple Ca2+-binding sites in the STIM1 luminal domain by an independent technique (Fig. 3d–g). We chose a competitive binding experiment because it would also illuminate a blind spot of ITC—the ITC titration is designed to use concentrations of protein in excess of Kd and does not directly report free Ca2+ at any point in the titration. The rationale of the competitive binding experiment (Fig. 3d) is that the fluorescent Ca2+ sensor D4 at trace levels can report free Ca2+ but, due to its low concentration in the incubation (150 nM here), will not appreciably alter free Ca2+. A Ca2+-binding competitor protein, in this case EFSAM, that is present at a fixed concentration will bind a fraction of added Ca2+ at each step in the titration and shift the titration curve. D4 surveys Ca2+ concentrations in the range from tens to hundreds of μM (ref. 36), and was chosen as the fluorescent Ca2+ sensor based on the ITC measurements of Fig. 3a.

In a control titration including 35 μM GrpE, binding of Ca2+ to the D4 sensor was fitted with Kd 200 μM (Fig. 3e), in line with the published value for D4 alone36. Inclusion of EFSAM(D76A)-GrpE at 35 μM caused no shift in the titration curve, indicating no detectable binding of Ca2+ to the D76A protein (Fig. 3f). Inclusion of wild-type EFSAM-GrpE at 35 μM resulted in clear competition, and the competition could not be accounted for by a single Ca2+-binding site (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 3). We estimated free Ca2+ at each step in the titration from the D4 signal, and Ca2+ bound to EFSAM as the difference between total Ca2+ added and free Ca2+ (Fig. 3h). The resulting binding relation for EFSAM is plotted in Fig. 3i. The main conclusion is that ~6 sites per monomer are occupied in the range of Ca2+ studied. Occupancy of most of these sites (5–6 sites) takes place in the range from 50–400 μM Ca2+, suggesting that the sites are physiologically relevant for ER-luminal Ca2+ binding.

A surface implicated in Ca2+ binding and STIM relocalization

There are 21 aspartate or glutamate residues in the NMR structure of STIM1 EFSAM domain that are neither EF-hand Ca2+ ligands nor in close contact with other parts of the protein. We replaced aspartate with asparagine (D > N) and glutamate with glutamine (E > Q)— conservative and sterically similar replacements that neutralize the negative charge— in three spatially separate groupings of these EFSAM acidic residues (Fig. 4a), on the premise that function would be affected if the substituted region contributes to Ca2+ binding and stabilizes inactive STIM1. The three altered STIM1 proteins were designated STIM1-1NQ, STIM1-2NQ, and STIM1-3NQ.

Fig. 4.

Identification of an EFSAM surface that regulates STIM1 Ca2+ binding and puncta formation. a Three sets of surface residues (stick representation) studied in this work, marked on the cartoon diagram of EFSAM structure (PDB ID: 2K60). Region 1 comprises four acidic residues near the EFSAM N terminus, region 2 comprises eleven acidic residues spanning the exposed surface of the two EF-hands, and region 3 comprises six residues on a surface of the SAM domain. b Confocal micrographs of HeLa cells expressing eGFP-STIM1-1NQ, eGFP-STIM1-2NQ, eGFP-STIM1-3NQ, or wild-type eGFP-STIM1, at rest (left panels) and after store depletion with 1 μM thapsigargin (TG) (right panels). Scale bars, 5 μm. c ITC analysis of EFSAM-2NQ. Top panel, heat changes measured by injecting 1 μl aliquots of 25 mM Ca2+ into a sample cell containing initially 252 μM protein. Bottom panel, integrated binding isotherm as a function of molar ratio (Ca2+: protein) after subtracting heats of dilution

STIM1-1NQ and STIM1-3NQ displayed an ER-like pattern in unstimulated cells and relocalized to ER-plasma membrane junctions after store depletion (Fig. 4b). These results do not support a major role for region 1 or region 3 acidic residues in stabilizing the inactive conformation of STIM1.

STIM1-2NQ, unexpectedly, showed little or no relocalization after store depletion (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Note 1). This effect is opposite to the expected effect of a simple loss of stabilizing Ca2+-binding sites, and Supplementary Figs. 4, 5, 6, and 7, and Supplementary Note 2 provide compelling evidence that reducing Ca2+ failed to trigger an activating conformational change in the STIM1-2NQ cytoplasmic domain. The D > N and E > Q substitutions in EFSAM-2NQ did, in fact, alter Ca2+ binding markedly, since ITC showed that only a single Ca2+-binding site was occupied in the concentration range monitored (Fig. 4c). We return later to the question whether a less extensive set of replacements in region 2 can separate the effect on Ca2+ binding from the negative effect on STIM1 activation.

Loss of Ca2+ has little impact on EFSAM secondary structure

It seemed likely that the 2NQ mutations interfered either with the EFSAM conformational change or with the EFSAM–EFSAM dimer interaction underlying activation. We focused on the conformational change by examining the 2NQ and wild-type EFSAM-GrpE fusion proteins using far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, which reports on secondary structure and, in particular, on α-helix content. The α-helix content of both EFSAM-2NQ-GrpE and wild-type EFSAM-GrpE in the presence of Ca2+ was in line with the NMR structure of the STIM1 EFSAM domain (Fig. 5a, b)8, and in fact the secondary structure of EFSAM-2NQ was indifferent to the presence or absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 5b), in line with our hypothesis. However, these experiments produced the completely unexpected finding that wild-type EFSAM-GrpE exhibited only a minor loss of secondary structure in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 5a), not the massive unfolding that has been observed with the isolated EFSAM domain.

Fig. 5.

Limited change in EFSAM secondary structure after Ca2+ depletion. a–c Far-UV CD spectra of WT EFSAM-GrpE, EFSAM-2NQ-GrpE, and EFSAM(D76A)-GrpE, each protein 5 μM, in the absence or presence of Ca2+. d–g Examples of deuterium uptake into four peptic peptides of EFSAM WT, D76A and 2NQ in Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound forms, at 0.5, 1, 2 and 5 min time points, determined by HDX–MS. h Deuterium exchange into EFSAM peptides of wild-type, D76A, and 2NQ proteins, in 0 Ca2+ or 30 μM Ca2+, at the 0.5 min time point. The peptides from d–g are marked with arrowheads. Supplementary Fig. 9b presents the data for all time points. i Differences in deuterium exchange between the inactive and active forms of wild-type EFSAM (WT(Ca2+-bound)–WT(Ca2+-free)), between the active form of wild-type EFSAM and the D76A protein (WT(Ca2+-free)–D76A(Ca2+-free)), and between the inactive form of wild-type EFSAM and the 2NQ protein (WT(Ca2+-bound)–2NQ(Ca2+-bound)), at the 0.5 min time point. Data are the averages of triplicate measurements. j Spatial positions of the low-exchanging peptide (EVIQWLIT; green) and two flanking higher-exchanging peptides (WKAWKSSEVYNWTVDE and YVELPQYEET; orange) highlighted on the Ca2+-bound WT EFSAM structure (PDB ID: 2K60)

To verify that we could observe a loss of EFSAM secondary structure by CD if it occurred, we followed the thermal denaturation of EFSAM-GrpE. EFSAM-GrpE showed a clear decrease in α-helical secondary structure between 25 ∘C and 65 ∘C (Supplementary Fig. 8). In contrast, GrpE showed only a minimal decline in α-helical structure in this temperature range, in keeping with published evidence that the main unfolding transition of GrpE occurs above 90 C (ref 37).

The EF-hand mutation D76A compromises STIM1 Ca2+ binding and thus provides an independent way to examine the effect of Ca2+ dissociation on STIM1 protein structure. The far-UV CD spectrum of EFSAM(D76A)-GrpE was comparable to the spectrum of the wild-type protein in the absence of Ca2+, reflecting a largely α-helical structure, and was unchanged by addition of Ca2+ (Fig. 5c). Thus any loss of helical structure in the Ca2+-free EFSAM domain is minor, and Ca2+ sensing reflects a Ca2+-dependent conformational rearrangement between two folded protein structures.

H-D exchange shows that Ca2+-free EFSAM is structured

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange–mass spectrometry (HDX–MS) is a sensitive way to probe local structure and dynamics of the protein backbone. A standard protocol is to expose the protein briefly to D2O, then minimize further H-D exchange in a low-pH buffer, digest with pepsin, and measure incorporation of deuterium into identified peptic peptides by LC-MS. Deuterium is rapidly incorporated at backbone –NH groups in unstructured regions of the protein. On the other hand, backbone sites that are hydrogen bonded or inaccessible to solvent are protected from rapid H-D exchange. Protection is not absolute, but depends on the time scale probed, and hence the time course of exchange yields additional information on local backbone dynamics.

We subjected wild-type EFSAM-GrpE to deuterium exchange for periods ranging from 0.5–5 min, in the presence of 30 μM Ca2+ and in the absence of Ca2+, and assessed deuterium incorporation (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Ca2+-bound EFSAM exhibited substantial protection from exchange, consistent with its known folded structure (Fig. 5d–h). Ca2+-free EFSAM showed altered deuterium uptake throughout the EF-hand and SAM domains, but uptake was altered in an unexpected direction: the backbone –NH groups were detectably more protected from exchange in the absence of Ca2+ across nearly the entire EFSAM sequence (Fig. 5h, Supplementary Fig. 9b). Only a single short section, the peptide 136EVIQWLIT143, stood out for its contrasting pronounced protection in 30 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 5f, h). In counterpoint, peptides flanking this section— 121WKAWKSSEVYMWTVDE136 and, at 5 min, 144YVELPQYEET153— exhibited a greater increase in H-D exchange in the presence of Ca2+ than the remainder of the protein (Fig. 5e, h, Supplementary Fig. 9b).

HDX–MS data for EFSAM(D76A) and EFSAM-2NQ buttressed the evidence that there are two structured states of EFSAM. H-D exchange in these proteins was almost Ca2+-insensitive, and, broadly speaking, each mutant protein mirrored one state of wild-type EFSAM: Exchange in EFSAM(D76A) was similar to exchange in wild-type EFSAM in the absence of Ca2+, and, conversely, exchange in EFSAM-2NQ largely matched exchange of wild-type EFSAM in the presence of 30 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 5h, Supplementary Fig. 9b–d, Supplementary Note 3).

Measurements with intrinsic and extrinsic fluorescent probes (Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Note 4) further support the conclusion from the CD and HDX–MS experiments that there are structured conformations of EFSAM at both endpoints of the high Ca2+–low Ca2+ conformational change.

EFSAM does not unfold in full-length STIM1

To determine whether EFSAM in full-length STIM undergoes obligatory unfolding when it transitions to the active dimeric form, we probed whether cysteine residues engineered at sites that are buried or partially buried in Ca2+-bound EFSAM-GrpE become exposed upon dissociation of Ca2+ from full-length STIM1 in ER membranes. We engineered a panel of constructs appropriate for the experiment, and carried out the experiment in parallel with full-length STIM1 in ER membranes and with EFSAM-GrpE. Except for one M > C replacement, the engineered proteins had relatively conservative V > C, T > C, and S > C replacements at sites that are buried or partially buried in the NMR structure. All the mutant STIM proteins (expressed as GFP-STIM1) responded to depletion of ER Ca2+ stores by forming STIM1 puncta (Supplementary Fig. 11). The S126C, V129C, and V198C mutants— and to a lesser extent the A168C mutant— had noticeable STIM1 fluorescence remaining in the deeper ER after store depletion, suggesting that these four mutants might be less strongly activated by store depletion.

We prepared HeLa cell membranes in the same way as for STIM1-STIM1 crosslinking experiments, where we have shown that STIM1 undergoes a conformational change in response to Ca2+ (ref. 28 and this manuscript). We incubated the membranes in buffer with 0.5 mM EGTA or 2 mM Ca2+, probed exposure of the individual engineered cysteine residues by reaction with biotin-maleimide, then captured biotinylated proteins on streptavidin resin, followed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blotting for STIM1. The residues tested showed similar low accessibility in the presence of Ca2+ for full-length STIM1 and for EFSAM-GrpE (Fig. 6, Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12a). The exposed S58C control was well labelled in both proteins, and the buried cysteine residues in EFSAM-GrpE became exposed and could be labelled upon denaturation with 6 M urea. However, only minor changes in accessibility of the individual buried residues were seen in the two proteins when comparing the Ca2+ and EGTA conditions. Thus, the EFSAM domain of full-length STIM1 did not unfold upon dissociation of Ca2+.

Fig. 6.

Exposure of buried EFSAM cysteine residues in STIM1 is insensitive to Ca2+ depletion. a Ribbon structure of Ca2+-bound EFSAM (PDB ID: 2K60). Red highlighting indicates the placement of engineered cysteine residues to probe possible EFSAM unfolding. Cysteine replacement of the fully exposed residue S58 was a positive control. b Anti-STIM1 western blots of cysteine-substituted HA-tagged STIM1 or GFP-STIM1 proteins. Proteins were labelled in HeLa cell membranes by incubation with biotin-maleimide, in the presence of EGTA or Ca2+ as indicated, then solubilized, bound to streptavidin, and eluted in SDS sample buffer. Each construct and condition is represented by a pair of lanes: input (In), 2.5% of the material applied to the streptavidin beads; and pulled down (Pd), all material recovered from the beads. The exposed-residue control, HA-tagged STIM1(S58C) in the first four lanes of the upper left gel, was amply biotinylated (Pd lanes). Endogenous STIM1 migrates with HA-STIM1(S58C) and contributes to anti-STIM1 staining of the HA-STIM1(S58C) input lanes. However, it does not contribute to the signal from biotinylated protein (Pd lanes), since endogenous STIM1 detected as the lower band (**) in all other samples (In lanes) was not biotinylated (Pd lanes) in those samples. For the cysteine-substituted GFP-STIM1 samples, detection of biotinylated protein (Pd lanes) in the upper band is the parameter of interest. The uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 12

Exposure of residues S126C, V129C, and V137C appeared somewhat higher in 2 mM Ca2+ than in EGTA, reminiscent of the greater deuterium exchange into the peptide 121WKAWKSSEVYMWTVDE136 in the presence of Ca2+, but further detailed experiments will be needed to determine whether this indicates local unfolding.

EFSAM surface residues tune STIM1 Ca2+ sensitivity

We returned to the question whether EFSAM Ca2+ binding can be perturbed without preventing STIM1 activation. Examining a series of STIM1 proteins mutated at a subset of the 2NQ sites for altered resting localization of GFP-STIM1 led to the discovery of STIM1-2NQ(6–11), a protein with N/Q substitutions only at E94, D100, E111, D112, E118, and D119. STIM1-2NQ(6–11) was partially constitutively activated, as evidenced by the presence of some puncta already in resting cells, and by the prominent appearance of puncta upon brief exposure to Ca2+-free solution (Fig. 7a). The latter ‘hair-trigger’ response was not characteristic of cells expressing wild-type STIM1 (compare Fig. 7a, b, middle panels), and presumably arose from a heightened sensitivity to the limited store depletion that occurred during a brief period in Ca2+-free solution, due to Ca2+ extrusion unbalanced by resting Ca2+ influx. Reflecting the partial constitutive activation, cells expressing STIM1-2NQ(6–11) showed constitutive Ca2+ entry through ORAI channels (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

Effect of 2NQ(6-11) mutations on EFSAM Ca2+ sensing. a–b Confocal micrographs of GFP-STIM1-2NQ(6-11) (6-11; a) and GFP-STIM1 (WT; b) at rest (2 mM Ca2+; left panels), during a 10-min exposure to Ca2+-free solution (0 mM Ca2+; middle panels), and following store depletion with 1 μM TG (right panels). Scale bars, 5 μm. c Single-cell [Ca2+]i measurements in HeLa cells expressing mCherry-ORAI1 and wild-type GFP-STIM1 (WT; n = 220), GFP-STIM1-2NQ(6-11) (6-11; n = 258), or GFP-STIM1-2NQ (2NQ; n = 193), or in non-transfected HeLa cells (HeLa; n = 220). Cells were exposed to solutions containing varied concentrations of CaCl2 or 1 μM thapsigargin (TG) as indicated. d ITC analysis of EFSAM-2NQ(6-11). Top panel, heat changes measured by injecting 1 μl aliquots of 10 mM Ca2+ into a sample cell containing initially 100 μM protein. Bottom panel, integrated binding isotherm as a function of molar ratio (Ca2+: protein) after subtracting heats of dilution. Total Ca2+ at 70 min is the amount added to the ITC cell up to that point, corrected for the increase in volume, and free Ca2+ is calculated as total Ca2+ minus bound Ca2+ assuming five sites are occupied in EFSAM. e Western blot showing crosslinking of STIM1(A230C)-2NQ(6-11) in cellular membranes incubated at the specified Ca2+ concentrations. The black arrow marks the STIM1 monomer band, and the red arrow marks the dimer band. The uncropped blot is shown in Supplementary Fig. 12. f STIM-STIM dimer formation for STIM1(A230C)-2NQ(6-11) at each Ca2+ concentration is compared to the corresponding dimer formation for STIM1(A230C). Data from three independent experiments are plotted as mean ± SEM

In vitro experiments established the basis of the partial constitutive activation. ITC still reported ~5–6 Ca2+-binding sites in EFSAM-2NQ(6–11), but the heat released upon Ca2+ binding to EFSAM-2NQ(6–11) was reduced compared to that with wild-type EFSAM (Fig. 7d; compare Fig. 3a), indicating that Ca2+ binding was perturbed. Heat release is not in itself a measure of the free energy change ΔG or of binding affinity, but a larger total amount of Ca2+ was injected to reach the endpoint of the EFSAM-2NQ(6-11) titration curve in the ITC experiments even though protein concentration in Fig. 7d was comparable to that of wild-type protein in Fig. 3a, suggesting that the binding was of lower affinity. To test this hypothesis, we employed a direct assay of STIM1 conformational change. Oxidative crosslinking at residue A230C in a cysteineless STIM1 background measures apposition of the STIM1 transmembrane helices28. In ER membranes with ‘wildtype’ STIM1(A230C), the Ca2+ concentration dependence of crosslinking28 mirrors the concentration dependence of STIM1 activation in cells34,35, whereas the permanently active STIM1(D76A) protein crosslinks regardless of ambient Ca2+ concentration28. Tellingly, in this assay, the Ca2+ dependence of the conformational change of STIM1(A230C)-2NQ(6–11) in isolated ER membranes was shifted rightward into or beyond the range of resting ER Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 7e, f and Supplementary Fig. 12b). As in the case of STIM1-2NQ, we can draw no certain conclusion whether the replaced residues are themselves Ca2+ ligands or whether they affect Ca2+ binding at separate EFSAM surface sites allosterically. The central point is that the 2NQ(6-11) replacements both alter STIM1 Ca2+ binding at EFSAM surface sites and shift the Ca2+ concentration dependence of STIM1 activation in vitro and in cells.

Discussion

We designed the dimeric EFSAM-GrpE protein to incorporate some of the geometric constraints imposed on the STIM1 luminal domains in cells by their linkage to the STIM1 transmembrane helices and the dimeric STIM1 cytoplasmic domain. We show here that Ca2+ dissociation from EFSAM-GrpE or from full-length STIM1 controls a switch between two structured conformations of the EFSAM domain; that Ca2+ at physiological concentrations occupies multiple sites in the EFSAM domain, not solely the EF-hand site; and that the additional EFSAM Ca2+-binding sites are required together with the EF-hand site to control physiological activation of STIM1 in cells. We show further that Ca2+ binding at the EF-hand and Ca2+ binding at the EFSAM surface sites are energetically coupled, as evidenced by the fact that binding to the EF-hand enables or stabilizes binding to the other sites (Fig. 3a–c). The coupling in the reverse direction has not been examined experimentally, but it is required by thermodynamic considerations (Fig. 8). Our findings compel us to revisit the mechanism at the heart of STIM1 Ca2+ sensing.

Fig. 8.

Energetic coupling of the EF-hand site and the EFSAM surface sites. Equilibrium diagram for four selected states of an idealized EFSAM protein at a fixed Ca2+ concentration. (States with intermediate levels of Ca2+ binding that would be present in equilibrium with those represented are considered below.) For each state represented, five surface Ca2+-binding sites are indicated above EFSAM and the EF-hand site is indicated below, with bound Ca2+ depicted by the filled ellipses. Note that ‘EFSAM’ denotes the protein, not one particular protein conformation. For example, Ca2+-free EFSAM (at left) and EFSAM with Ca2+ bound to the EF-hand (at top) would differ in conformation. The ΔG parameters—free energy differences between pairs of states— are functions of Ca2+ concentration. At a given Ca2+ concentration, though, each ΔG value is uniquely defined, and ΔG1 + ΔG2 = ΔG1’ + ΔG2’ (6). The individual ΔG values and their Ca2+ dependence need not be determined in order to understand the energetic coupling. We make only the assumption that the poor binding of Ca2+ at physiological concentrations to the surface sites of EFSAM(D76A) reflects comparable poor binding to wild-type EFSAM when Ca2+ is not present in the EF-hand site. Then binding at the EF-hand favours binding at the other sites collectively (ΔG2 < ΔG2’), and equation (6) requires that collective binding at the EFSAM surface sites favours binding at the EF-hand (ΔG1’ < ΔG1). Notice that an analogous argument can be made for any state having one, two, three, or four surface Ca2+ sites occupied, as long as that state is present at an appreciable concentration in wild-type EFSAM at some Ca2+ concentration in the physiological range. This logic supports the broad conclusion that binding at the EFSAM surface sites favours binding at the EF-hand site

A starting point for this analysis is the Ca2+-dependent conformational change observed with both EFSAM-GrpE and full-length STIM1. The local rearrangement of EFSAM upon Ca2+ binding is likely to be similar in EFSAM-GrpE and full-length STIM1, but full-length STIM1 couples the local rearrangement to a concerted conformational change of the entire protein19,26–28. We have proposed above that the energetic cost associated with the concerted conformational change explains why the titration curve for the FRET signal of EFSAM-GrpE or EFSAM-SAH-GrpE (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 1g) is centred at 1–10 μM Ca2+, whereas the titrations for STIM1 translocation to ER-plasma membrane junctions34,35 and for disulfide crosslinking of STIM1 transmembrane segments in ER membranes28 are centred at ~200 μM Ca2+. The challenges are to relate the conformational change to Ca2+ binding given that there are now two classes of Ca2+-binding sites to consider, and to explain why altering Ca2+ binding at surface sites affects the concentration dependence of the conformational change.

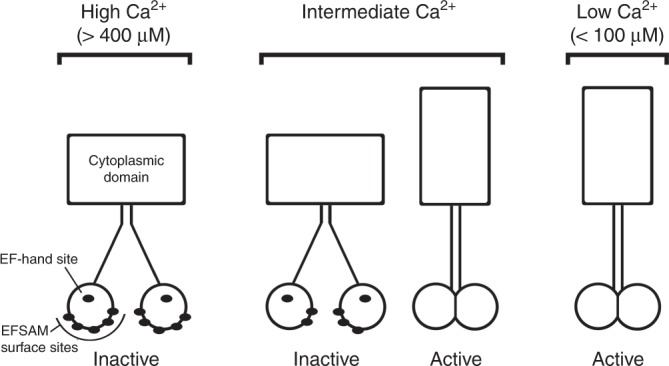

A straightforward interpretation retains the assumption that STIM1 relocalization in cells and STIM1–STIM1 crosslinking in membranes are elicited by dissociation of Ca2+ from the EF-hand site, and hence that half-maximal dissociation of Ca2+ from the EF-hand site occurs at ~200 μM Ca2+. The additional elements that must be incorporated in light of experiments reported here are that the EFSAM surface sites bind Ca2+ in that same concentration range (Fig. 3a, i, Supplementary Fig. 10d), that Ca2+ binding at the EFSAM surface sites stabilizes binding at the EF-hand site, and that the EFSAM surface sites are coupled to the EF-hand site in a way that requires Ca2+ dissociation from the EFSAM surface sites prior to STIM1 activation (Fig. 9). With this interpretation, the activation curve of the STIM1-2NQ(6-11) mutant is shifted to the right because higher Ca2+ concentrations are needed for occupancy of the EFSAM surface sites, and therefore, due to energetic coupling, for binding to the EF-hand site.

Fig. 9.

Relation between Ca2+ binding and STIM1 conformational change in cells. Schematic depiction of Ca2+ (black ellipses) bound to EFSAM, in the context of STIM1 dimers, to illustrate the progressive changes in STIM1 that accompany depletion of ER Ca2+ stores. The model retains the assumption that Ca2+ binding at the EF-hand controls the conformational change. At high levels of ER Ca2+, all EFSAM Ca2+-binding sites are occupied, and EFSAM is inactive. At low levels of Ca2+, no sites are occupied, and EFSAM is active. (The relevant values of ER free Ca2+ are taken from the literature34, 35.) At intermediate Ca2+, there is a mixture of STIM1 dimers, with some resembling the high-Ca2+ case but having fewer Ca2+ bound to EFSAM surface sites, and others having no Ca2+ bound. Only a representative ‘inactive’ dimer is illustrated here. The fact that there are dimers with other levels of surface-site occupancy, and possibly mixed STIM1 dimers with the EF-hand site occupied in only one monomer, would not alter the argument materially. The salient point—taught by EFSAM(D76A) in Fig. 3c, f— is that there will be no EFSAM domain with the EF-hand site empty and surface sites occupied. Stated simply, Ca2+ must dissociate both from the EFSAM surface sites and from the EF-hand during activation

A second more radical interpretation posits that Ca2+ in fact binds to the EF-hand site in full-length STIM1 at low micromolar concentrations, just as it does in EFSAM-GrpE or EFSAM-SAH-GrpE (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 1g), but that EF-hand site occupancy alone is not sufficient to stabilize full-length STIM1 in its inactive conformation. In this case, STIM1 relocalization in cells and STIM1–STIM1 crosslinking in membranes would be controlled mainly by Ca2+ binding to and dissociation from EFSAM surface sites, and the shifted Ca2+ sensitivity of STIM1-2NQ(6-11) would be accounted for by the altered binding at those sites without invoking the coupling to the EF-hand site. Measurements of Ca2+ binding to full-length STIM1 in cells or in ER membranes will be necessary to distinguish between these scenarios. Such measurements could also address the possibility, admissible under either scenario, that Ca2+ binding at some of the EFSAM surface sites is further stabilized as part of an EFSAM-protein or EFSAM-lipid interface.

The prevailing model for STIM1 Ca2+ sensing has been built on studies of the isolated recombinant EFSAM domain8,21–24. Isolated EFSAM differs from EFSAM-GrpE in two key respects: It has a propensity to unfold at low Ca2+ concentrations, and it exhibits negligible Ca2+ binding at 10 μM Ca2+, whether binding is measured directly as 45Ca2+ binding or indirectly as conformational stabilization. The unfolding simply reflects poor structural stability of the isolated EFSAM domain in the absence of Ca2+. The inability of Ca2+ to bind and stabilize isolated EFSAM at concentrations that elicit a conformational change of EFSAM-GrpE could have same root cause—unfolding of isolated recombinant EFSAM is energetically favored at low Ca2+ concentrations, and thus EF-hand Ca2+ binding is opposed by the unfavorable free energy change of refolding the protein.

Early quantitative studies of Ca2+ binding to isolated EFSAM found a single 45Ca2+-binding site per monomer8,21. Furukawa et al. subsequently reported that an isolated EFSAM domain, purified and refolded under different conditions, exhibited a secondary-structure change that was cooperative with respect to Ca2+ concentration, with Hill coefficient 4.7 (ref. 24). This finding might have led to a re-evaluation of the number of Ca2+-binding sites in EFSAM, but Furukawa et al. instead attempted to explain the cooperativity on the basis of a single Ca2+-binding site per monomer, and did not determine the number of binding sites experimentally. It seems more likely in light of our current data that the Furukawa EFSAM preparation had multiple Ca2+-binding sites, and that the structural change reflected cooperative binding at the EF-hand and surface Ca2+-binding sites. The stoichiometry of physiological Ca2+ binding is central to understanding STIM1 Ca2+ sensing, because the overall process of Ca2+ dissociation, STIM1 oligomerization, and STIM1 redistribution in cells is a steep function of ER Ca2+ concentration, with Hill coefficient in the range 4–8 (refs. 34,35). Based on the premise that there is only a single Ca2+-binding site per monomer, STIM1 oligomerization has been thought to play a dominant role in this cooperativity. Our results indicate that it is time to reconsider this interpretation.

Our analysis of Ca2+ binding to EFSAM-GrpE and the associated protein conformational changes offers a fresh perspective on physiological Ca2+ sensing by STIM1. The next obvious steps are to define the additional Ca2+-binding sites structurally, and to investigate the extent to which Ca2+ dissociation from the multiple sites contributes to the cooperativity of STIM1 activation. Perhaps most intriguingly, the finding that EFSAM does not unfold upon dissociation of Ca2+ will spur renewed efforts to define the structure of the EFSAM–EFSAM dimer that triggers STIM1 activation.

Methods

Plasmids for bacterial and mammalian expression

Thermus thermophilus HB8 GrpE genetic sequence was synthesized commercially (Genewiz), based on sequence information from PDB (ID: 3A6M; GenBank nucleotide sequence: AB012390.1 (2222–2755 bp). The synthesized GrpE, nucleotides 2222-2734, was PCR amplified and cloned between SacI and NotI sites of pET28a vector (Qiagen) to generate the His6-tagged GrpE expression construct. The cDNA encoding mouse EFSAM sequence (STIM1 residues 58-209) was PCR amplified and cloned at the NdeI and SacI sites of pET28a vector at the 5’ end of the GrpE sequence for the His6-tagged EFSAM-GrpE expression clone, resulting in a construct encoding EFSAM(58-209)–LELSRANSSTLAAVTSGSEL–GrpE(1-171). The D76A mutation was introduced into the pET28-EFSAM-GrpE plasmid using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent). The single-cysteine EFSAM constructs used for energy transfer experiments were generated by PCR amplification of EFSAM-GrpE, introducing nine nucleotides encoding the protein sequence –CGG– immediately N-terminal to EFSAM residue 58, and cloned into pET28a vector. The 100-residue Single Alpha Helix (SAH) construct (pBIEX1-SAH) from Sus scrofa myosin VI is a kind gift from Dr. Sivaraj Sivaramakrishnan, University of Minnesota. The SAH domain was introduced between EFSAM and GrpE sequences using BstBI and AvrII to generate pET28-EFSAM-SAH-GrpE. Expression constructs encoding EFSAM mutated in the surface sites of regions 1, 2, and 3 were generated by mutagenesis of pET28-EFSAM-GrpE plasmid using a commercial service (Genewiz). The 1NQ variant of EFSAM-GrpE contains the mutations E59Q, D60N, E61Q, and E66Q; the 11 mutations of the 2NQ variant are D77N, D82N, E86Q, D89N, E90Q, E94Q, D100N, E111Q, D112N, E118Q, and D119N; and the six mutations of the 3NQ variant are E128Q, D135N, E136Q, E151Q, E152Q, and D183N. The single-cysteine EFSAM-GrpE mutants used for biotinylation experiments were generated by mutagenesis of the pET28-EFSAM-GrpE plasmid using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent).

The HA-tagged STIM1 construct and eGFP-STIM1 are described in detail in ref 28. Two restriction sites, BsiWI at the 5’ end and MluI at the 3’ end of the mutated regions, were introduced into the pET28-EFSAM-GrpE to facilitate subcloning of the surface variants. Segments of DNA encoding the surface mutations were spliced into the mammalian vectors using PCR amplification and standard subcloning steps. The single-cysteine eGFP-STIM1 mutants used for biotinylation experiments in cellular membranes were generated by mutagenesis of the eGFP-STIM1 plasmid using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent).

The cDNA encoding STIM2(1-434) was PCR amplified and cloned into the pEGFP-N1 vector using XhoI and BamHI sites to generate STIM2(1-434)-WT-GFP. Subsequently, the D167A mutation was introduced into the STIM2(1-434)-WT-GFP plasmid using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent). The STIM2(1-434)-2NQ-GFP insert was synthesized using commercial services (Genewiz) and encodes the following ten mutations: D168N, E177Q, D180N, E181Q, E185Q, D191N, E202Q, D203N, E209Q and D210N. pET28-STIM2-EFSAM-GrpE was generated by cloning the cDNA corresponding to STIM2(149-299) between NdeI and SacI sites of the pET28-EFSAM-GrpE plasmid.

The pEX-SP-CFP/YFP-STIM1(23-685) constructs used for live-cell FRET measurements were a kind gift from Dr. Tobias Meyer, Stanford University. pEX-SP-CFP/YFP-EFSAM-TC-GrpE plasmids were made by subcloning PCR-amplified fragments of EFSAM-TM-CC1 (encoding human STIM1 residues 58-343) and GrpE into KpnI-AgeI and AgeI-NotI sites, respectively, at the 5’ ends of the CFP/YFP coding sequences in place of the full-length STIM1 inserts.

The oligonucleotide primers utilized for PCR amplifications and mutagenesis are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Protein purification

Plasmids encoding EFSAM-GrpE variants were transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (NEB) for efficient protein expression. The transformed cells were grown at 37 °C. Protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when OD600 of the culture reached 0.6, followed by incubation for 12 h at 16 °C. Harvested cells were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM CaCl2, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 mM β-mecaptoethanol, and Roche protease inhibitors (1 tablet per 50 ml buffer), and sonicated. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the lysate was applied to Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA)-agarose resin (Qiagen). Bound recombinant proteins were eluted in lysis buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. Proteins were further purified by gel filtration on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in the presence of 20 mM CaCl2, 5 mM EGTA, or Chelex-treated Ca2+-free buffer (Chelex-100 resin, Bio-Rad), with 2 mM TCEP (tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine). Eluted proteins were concentrated using Amicon Ultra 30 kDa concentration devices (EMD Millipore).

Protein conjugation with fluorescent dyes

Single-cysteine-containing EFSAM-GrpE variants were labelled either singly with fluorescein-5-maleimide (Thermo) or Alexa Fluor 594 C5 maleimide (Thermo), or with both fluorophores, for in vitro energy transfer measurements. Each protein sample, ~100 μM in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, was first treated with 10 mM TCEP for at least 1 h to reduce any disulfide bonds. Excess TCEP was removed by passing the fully reduced protein sample through an Amicon 30 kDa device with a quick buffer exchange using 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl buffer. Dye working stocks (10–20 mM) were prepared in anhydrous DMF immediately prior to use. A 10-fold molar excess of the fluorescent dyes was added slowly to the protein and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. The labelled protein was passed through a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) and further concentrated. Labelled proteins yielded a ~ 0.8-0.9:1 molar ratio of fluorophore to protein, based on measuring the absorbance at 495 nm (fluorescein-5-maleimide, ε495 = 68,000 M-1 cm-1), 588 nm (Alexa Fluor 594 C5 maleimide, ε588 = 96,000 M-1 cm-1), and 280 nm (protein, ε280 = 34,950 M-1 cm-1). Dye conjugation to each protein was further confirmed by resolving the labelled proteins on a 4–12% NuPAGE gel (Life Technologies) and imaging under a broad-range UV light using Gel Doc EZ (Bio-Rad).

Fluorescence spectrometry-based assays

For in vitro FRET measurements, fluorescence spectra were acquired at 22 °C using a QuantaMaster 40 spectrofluorometer (PTI). Protein concentration was 250 nM. The spectra were collected from 450 to 650 nm with the excitation set at fluorescein dye excitation wavelength (420 nm) and the slit widths set at 12 nm.

In the ANS dye-binding assay, 1.4 μM of the specified EFSAM-GrpE variant was mixed with 40 μM ANS (8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid) dye (Thermo) in a Chelex-treated buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol. The dye-mixed protein was incubated for 5 min before each spectral scan (λex = 370 nm) with the specified amounts of CaCl2 at 22 °C in dark. The slit width was set to 8 nm and the fluorescence emission spectra were acquired from 440 to 600 nm.

Tryptophan emission spectra (λex = 295 nm) were recorded from 310 to 420 nm for 1 μM wild-type EFSAM-GrpE and its variants, at 4 °C. The slit widths were set at 2 nm. Proteins incubated with 6 M GdCl were used to collect the denatured protein emission spectra.

D4 cameleon sensor expression vector, pBAD-D4, was a gift from Amy Palmer and Roger Tsien (Addgene plasmid #37473; ref. 36). 150 nM D4 sensor, resuspended in Chelex-treated buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 5% glycerol, was titrated with specified amounts of Ca2+, in the presence or absence of 35 μM EFSAM-GrpE variants. Emission spectra were recorded from 450 to 600 nm at λex = 410 nm with 2 nm slit width, at 22 °C.

In the D4 fluorescence competition assay, Ca2+ binding to D4 is proportional to the normalized intensity change y. Data points plotted in Fig. 3e–g were normalized as

| 1 |

where yMIN is the intensity measured in Ca2+-free solution, and yMAX the intensity in 25 mM Ca2+. The D4 standard binding curve in Fig. 3e–g is for binding to a single site with Kd 200 μM,

| 2 |

In Fig. 3i, data points from two experiments are plotted individually. Data in the individual experiments were normalized as above, with yMIN the average of the experimental fluorescence intensity values at 5 and 10 nM Ca2+, and yMAX the average of the values at 20 and 25 mM Ca2+. Free Ca2+ was estimated for each data point from y and the D4 standard curve with Kd 200 μM, as shown conceptually in Fig. 3h. The equation is

| 3 |

a rearrangement of Eq. (2). Bound Ca2+ was estimated as

| 4 |

Only the data points for total Ca2+ 10–500 μM are plotted in Fig. 3i, because there was no measurable binding at lower total Ca2+ concentrations, and the scatter in estimating bound Ca2+ by subtracting two large numbers became excessive at higher concentrations.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Ca2+ binding to EFSAM variants was measured using a MicroCal ITC-200 microcalorimeter (Malvern) at 20 °C. Chelex-treated buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol was used to dilute the proteins and Ca2+ stock. The buffer contained 2 mM Mg2+ where indicated. EFSAM-GrpE concentrations were calculated from A280 (measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer), after subtracting the buffer blank reading, using the tryptophan and tyrosine molar extinction coefficients determined by Edelhoch38 for tryptophan and tyrosine model compounds. (EFSAM-GrpE contains no cysteine/cystine.) Ca2+ was injected 39 times, 1 µl each, with 150 s intervals between injections. The background data obtained from the buffer sample were subtracted before the data analysis. The data were analyzed with the Origin7 software package (MicroCal).

It is possible to read the approximate number n of binding sites from a ‘Wiseman plot’ of the ITC data, such as the one in the right-hand panel of Fig. 3a. The original paper describing this method of analysis39 showed that under the experimental conditions used in ITC measurements, and for a protein having a single class of binding sites (that is, all the sites have the same Kd and ΔH), n corresponds approximately to the molar ratio of ligand to protein at the midpoint of the titration curve. This feature carries over when there is more than one class of sites, taking for n the molar ratio at the midpoint of the final phase of the titration curve, as illustrated by a collection of Wiseman plots in the literature40,41.

Fitting ITC data quantitatively requires adoption of a specific model, such as binding to a single class of sites, binding to two classes of independent sites, or in some cases a more complicated model. We did not attempt to fit the EFSAM ITC data to a detailed binding model because of the large number of Ca2+-binding sites, the interdependence of binding at the EF-hand and the other Ca2+-binding sites, and the coupling of Ca2+ binding to a change in intradimer EFSAM–EFSAM interactions. A quantitative description of binding would entail fitting a large number of Kd values, ΔH values, parameters for coupling between the sites, and parameters for coupling between binding at individual sites and the dimer > monomer conformational change. Mathematically, the data do not provide adequate constraints to fit so many parameters.

The standard software supplied with the MicroCal ITC-200 microcalorimeter has options to fit data to models with one or two classes of independent sites. We stress that these models are not appropriate for EFSAM, and that any estimated values for Kd and ΔH are not meaningful. However, the estimate for n may be credible, because any fit has to regress to the baseline in the region around the true value of n, independent of the model chosen. Using the MicroCal software to fit the data to a model with two classes of independent sites consistently yielded an estimate of 5–6 binding sites per EFSAM monomer.

Circular dichroism spectrometry

CD spectra of EFSAM-GrpE variants were recorded in an Aviv 62 DS spectropolarimeter at ambient temperature (~22 °C), using a 1-mm path length quartz cell with the protein concentration at 5 μM in Chelex-treated buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM or 10 mM Ca2+ where indicated. All spectra were obtained as the average of at least six scans with a scan rate of 50 nm/min. The ellipticity was measured from 190 nm to 260 nm and converted to mean residue ellipticity (deg cm2 dmol-1 res-1). For the experiment of Supplementary Fig. 8, CD spectra of EFSAM-GrpE and GrpE proteins were recorded after 2-min equilibration at the specified temperatures between 25 °C and 65 °C.

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange–mass spectrometry

The pepsin digestion profile of each EFSAM-GrpE variant was determined using 10 μM protein. For the deuterium exchange, deuterated Chelexed buffer, pD 7.5, was prepared by lyophilization of Chelex-treated buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and resuspension in D2O (Cambridge Isotopes). In pilot experiments, the number of EFSAM peptides reliably detected by MS after pepsin digestion decreased at Ca2+ concentrations higher than 30 μM. This concentration was acceptable for the HDX–MS experiments, since the FRET decrease of donor/acceptor-labelled EFSAM-GrpE was nearly complete at 30 μM Ca2+, and hence the defining conformational change induced by Ca2+ could be captured at 30 μM Ca2+. EFSAM proteins, in the presence or absence of 30 μM Ca2+, were diluted to 10 μM in the deuterated Chelexed buffer, quenched after 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 min with 125 mM sodium phosphate monobasic, pH 2.6 for 1 min, and injected into a Waters G2-Si HDX-MS system (Waters Corp.) by a LEAP H/DX PAL autosampler. Non-deuterated protein controls were processed in parallel. Protein samples were digested on-column with immobilized pepsin (Pierce) at 0 °C, then separated by liquid chromatography on a Waters NanoACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column with a 7–85% acetonitrile gradient in 0.1% formic acid. Peptides were analyzed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry with ion mobility separation in a Synapt G2-Si quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Peptides were identified with ProteinLynx Global Server (Waters Corp.). Mass spectra were assigned and H/D exchange was determined with DynamX 3.0 (Waters Corp.). The data were corrected for a back exchange loss of < 26%.

Biotinylation of exposed cysteine residues

HeLa cells ( ~ 6 × 106 cells per construct) were transfected with the specified single-cysteine constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 and grown under 10% CO2, in DMEM (HyClone media, Thermo) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS for 24 h. The cells were scraped from the substrate and resuspended in lysis buffer containing 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8 with NaOH), 25 mM NaCl, 12.5 U/ml DNase I (Thermo Fisher; catalog number 90083), protease inhibitors (Roche; catalog number 11873580001, 1 tablet per 50 ml buffer), 1 mM DTT, with either 0.5 mM EGTA (low Ca2+) or 2 mM Ca2+ (high Ca2+). Cellular membranes were prepared and resuspended in 200 μl resuspension buffer containing 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8) and 150 mM NaCl, with either 0.5 mM EGTA or 2 mM Ca2+. 300 μM biotin-maleimide reagent (Trilink; catalog number B-1012) was added to the resuspended membranes and the reaction was carried out for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction was quenched using 5 mM DTT and 200 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.5). The membranes were collected by centrifugation at 167,000 g for 20 min in an airfuge (Beckman Coulter) at 4 °C. The pellets were resuspended in 200 μl pulldown buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.5, and 150 mM NaCl. Once thoroughly resuspended, the membranes were solubilized with 0.5% Triton-X 100, 0.5% NP-40 and 0.5% SDS. The solubilized membranes were diluted further with 1200 μl of pulldown buffer and incubated with MyOne streptavidin T1 Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher). The beads were thoroughly washed thrice with pulldown buffer, boiled in 5x reducing loading/dye buffer to elute the biotinylated proteins and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen). Immunoblotting was performed using rabbit anti-STIM1 (Cell Signaling Technology #4916, 1:1000) and HRP-labelled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number A0545, 1:4000) and the blots were developed using ECL substrate (Perkin Elmer).

For assessing the biotinylation of EFSAM-GrpE single-cysteine mutants, the specified proteins were overexpressed in E. coli strain BL21 (NEB) and grown at 37 °C. Proteins were purified using Ni-NTA affinity purification as described above, without any added Ca2+. The purified proteins were passed through PD Minitrap G-25 desalting columns (GE Healthcare) to remove β-mecaptoethanol and imidazole. The proteins were eluted in biotinylation buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8) and 150 mM NaCl. 24 μM of the specified protein, containing either 0.5 mM EGTA or 2 mM Ca2+, and under native conditions (diluted using biotinylation buffer) or under denaturing conditions (diluted using 8 M urea; final urea concentration being 6 M), was treated with an equimolar amount of biotin-maleimide reagent for 5 min at room temperature. The biotinylation reactions were quenched directly with 5x reducing loading/dye buffer and the samples analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 4-12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen). Immunoblotting was performed using HRP-labelled goat anti-biotin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology #7075, 1:6000) and the blots were developed using ECL substrate (Perkin Elmer).

Cellular STIM1 expression and confocal microscopy

HeLa cells (ATCC) were transfected with the specified constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 and grown under 10% CO2, in DMEM (HyClone media, Thermo) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS for 24 h before imaging or crosslinking experiments. HeLa cells, transiently expressing wild-type eGFP-STIM1 or specified variants, were grown on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (MatTek). Imaging was performed using an Olympus Fv10.1 confocal laser-scanning microscope with a 60×, 1.35 NA, oil-immersion objective. Cells were imaged at room temperature, first in Ringer’s buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH), 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM D-glucose, for the resting-state images. This solution was replaced with a modified Ringer’s buffer lacking CaCl2 in the presence or absence of 1 μM thapsigargin (Life Tech), as specified, and incubated at least 5 min before obtaining the activated state images.

CFP-YFP live-cell FRET assay

HeLa cells co-expressing CFP- and YFP-tagged EFSAM-TC-GrpE protein pairs, corresponding full-length STIM1 protein pairs, or a tandem CFP-YFP construct were grown on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (MatTek) overnight. The pCMV-CFP-YFP control plasmid was a gift from Liusheng He and Jehonathan Pinthus (Addgene plasmid # 24520). A Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope equipped with 405-nm and 514-nm laser lines was used to collect CFP, YFP, and FRET images. The apparent FRET efficiency (expNFRET) between CFP- and YFP-labelled proteins was calculated with the help of PixFRET, an ImageJ-based plugin42.

mCherry-CAD relocalization assay

HeLa cells, co-transfected with mCherry-CAD and the specified variants of STIM2(1-434)-eGFP, were grown overnight in a modified DMEM medium containing 0.2 mM CaCl2 and 10 μM LaCl3 on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (MatTek). Imaging was performed using an Olympus Fv10.1 confocal laser-scanning microscope with a 60 ×, 1.35 NA, oil-immersion objective. Care was taken to obtain confocal sections at the mid-nuclear level of the cells, showing plasma membrane as well as cytoplasmic compartments. Cells were imaged at room temperature, first in Ringer’s buffer with no additional Ca2+, followed by Ringer’s buffer with 12 mM Ca2+. Fluorophore intensities were quantitated in regions of interest at the plasma membrane and cytoplasmic compartments using ImageJ. Statistical significance of the differences was determined using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

For the extracellular Ca2+ titration in Supplementary Fig. 6, HeLa cells were plated on 35-mm glass bottom cell culture dishes and transfected with STIM2(1-434)-eCFP and mCherry-CAD plasmids in DMEM medium. 18 h post-transfection, DMEM medium was switched to an imaging solution comprising 150 mM NaCl, 7.2 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 11.5 mM glucose, 20 mM HEPES adjusted to pH 7.2 with NaOH. After incubation in the Ca2+-free imaging solution for 10 min, live-cell imaging was carried out on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E microscope (Nikon Instruments) equipped with an A1R-A1 confocal module with LU-N4 laser sources (argon-ion: 405 and 488 nm; diode: 561 nm), CFI (chrome-free infinity) plan Apochromat VC series objective lenses (40 × oil), and a live-cell culture cage to maintain the cells at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Time-lapse imaging was performed to monitor the subcellular localization of mCherry-CAD upon addition of increasing amounts of external Ca2+ (0–25 mM). The cytosolic intensity of mCherry-CAD was analyzed by using the NIS-element AR software (version 4.0).

STIM1 Ca2+ concentration-dependent crosslinking assay

STIM1 crosslinking assay was performed as described in ref. 28. Briefly, HeLa cells expressing specified variants of STIM1(A230C) (~12 × 106 cells) were scraped from the substrate and resuspended in Chelex-treated (Chelex-100 resin, Bio-Rad) dilution buffer with no added EGTA or Ca2+. Cellular membranes were prepared and resuspended in 130 μl Chelex-treated resuspension buffer containing 25 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.3 mM DTT. Equal volumes of membranes were apportioned to twelve wells containing resuspension buffer supplemented to give either a final EGTA concentration of 0.5 mM or final Ca2+ concentrations ranging from 0.3 μM to 2 mM. Iodine oxidation, SDS-PAGE analysis, immunoblotting with anti-STIM1 antibody (Cell Signaing Technology #4916, 1:1000), and quantitation were as described in ref 28.

Single-cell Ca2+ influx assay

Single-cell Ca2+ imaging was performed using HeLa cells that had been co-transfected with eGFP-STIM1 variants and mCherry-ORAI1 (ref. 43), FACS-sorted for medium-level GFP-expressing cells, and plated on 18-mm coverslips. The cells were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester for 45–60 min at 37 °C in DMEM containing 0.02% Pluronic F-127 and 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, washed twice with fresh media, and analysed immediately. Modified Ringer’s solution used in this assay consisted of 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM D-glucose, and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH), with the addition of either 1 mM or 2 mM CaCl2, or 1 μM TG, where indicated. Coverslips were assembled into a chamber on the stage of an Olympus IX 71 microscope equipped with an Olympus UPLSAPO 20 × , NA 0.75, objective. Cells were alternately illuminated at 340 nm and 380 nm with the Polychrome V monochromator (TILL Photonics) using ET - Fura2 filter (Chroma Technology Corp., catalog number 79001). The fluorescence emission at λ > 400 nm (LP 400 nm, Emitter 510/80 nm) were captured with a CCD camera (SensiCam, TILL Imago). Ratio images were recorded at intervals of 4 s. Ca2+ concentration was estimated from the relation44

| 5 |

where Kd = 220 nM, and the values of Rmin, Rmax, and (Sf2/Sb2) were determined from an in situ calibration of Fura-2 in HeLa cells. Data were analyzed using TILL Vision (TILL Photonics).

Experimental replicates and statistical analysis

Data in Figs. 5a and 5c are representative of five experiments. Data in Figs. 1d, 3, 7a, b, d, and e are representative of three experiments. Data in Figs. 1f, g, 3a–c, e–g, 5b, and 6 are representative of two experiments. The conclusions from Fig. 6 for GFP-STIM1 cysteine mutants are supported by data from two similar experiments with HA-STIM1 cysteine mutants, which are not included here. Statistical significance of observed differences was determined using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Anjana Rao for discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by NIH grants AI084167 and GM110397 (to P.G.H.), AI040127 (to Anjana Rao and P.G.H.), NIH Shared and High-End Instrumentation Award S10OD21724 (to E.A.K.), NIH grants GM112003 and GM126532 (to Y.Z.), American Cancer Society grant RSG-16-215-01 TBE (to Y.Z.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant NSFC-31471279 (to Y.W.), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 2017EYT21 (to Y.W.), and postdoctoral fellowship 2016/12505-8 from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (to A.E.Z.).

Author contributions

A.G. and P.G.H. designed the experiments. A.G. was the lead scientist for all the protein engineering, biochemical and biophysical measurements, and cellular assays. A.E.Z. joined in identifying and characterizing STIM1-2NQ(6-11). N.H. contributed to the molecular cloning, protein purification, crosslinking, and fluorescence assays. V.R. developed the STIM1 crosslinking assay. A.A.B. carried out the ITC measurements. G.M., S.Z., Y.W., and Y.Z. engineered plasma membrane-anchored STIM, and developed the mCherry-CAD relocalization assay and advised on its application to the STIM2-2NQ mutant. E.A.K. guided and participated actively in the HDX–MS experiments. A.G. and P.H. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from the other authors.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. HDX–MS data have been deposited in the MassIVE database maintained by UCSD Centre for Computational Mass Spectrometry under accession code MSV000082950.

Competing interests

P.G.H. is a founder and scientific advisor of CalciMedica, Inc. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-06816-8.

References

- 1.Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Rao A. Molecular basis of calcium signaling in lymphocytes: STIM and ORAI. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2010;28:491–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soboloff J, Rothberg BS, Madesh M, Gill DL. STIM proteins: dynamic calcium signal transducers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:549–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 2015;95:1383–1436. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liou J, et al. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang SL, et al. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2005;437:902–905. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercer JC, et al. Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:24979–24990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604589200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spassova MA, et al. STIM1 has a plasma membrane role in the activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Proc. . Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:4040–4045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ikura M. Structural and mechanistic insights into STIM1-mediated initiation of store-operated calcium entry. Cell. 2008;135:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liou J, Fivaz M, Inoue T, Meyer T. Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc. . Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9301–9306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702866104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan JP, et al. SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:337–343. doi: 10.1038/ncb1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park CY, et al. STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell. 2009;136:876–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawasaki T, Lange I, Feske S. A minimal regulatory domain in the C terminus of STIM1 binds to and activates ORAI1 CRAC channels. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;385:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh CM, et al. Role of phosphoinositides in STIM1 dynamics and store-operated calcium entry. Biochem. J. 2009;425:159–168. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ercan E, et al. A conserved, lipid-mediated sorting mechanism of yeast Ist2 and mammalian STIM proteins to the peripheral ER. Traffic. 2009;10:1802–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muik M, et al. Cytosolic homomerization and a modulatory domain within STIM1 C terminus determine coupling to ORAI1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:8421–8426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800229200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covington ED, Wu MM, Lewis RS. Essential role for the CRAC activation domain in store-dependent oligomerization of STIM1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:1897–1907. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e10-02-0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y, et al. STIM1 gates the store-operated calcium channel ORAI1 in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang X, Jin H, Cai X, Li S, Shen Y. Structural and mechanistic insights into the activation of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) Proc. . Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:5657–5662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118947109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, et al. Initial activation of STIM1, the regulator of store-operated calcium entry. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:973–981. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muik M, et al. STIM1 couples to ORAI1 via an intramolecular transition into an extended conformation. EMBO J. 2011;30:1678–1689. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ames JB, Ikura M. Stored Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) via the EF-SAM region: an initiation mechanism for capacitive Ca2+ entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35855–35862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng L, Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Ikura M. Biophysical characterization of the EF-hand and SAM domain containing Ca2 + sensory region of STIM1 and STIM2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;369:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Ikura M. Stromal interaction molecule (STIM) 1 and STIM2 calcium sensing regions exhibit distinct unfolding and oligomerization kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:728–732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furukawa Y, et al. Intrinsic disorder mediates cooperative signal transduction in STIM1. J. Mol. Biol. 2014;426:2082–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]