Abstract

Digital images often suffer from contrast variability and non-uniform illumination, which seriously affect the evaluation of biomarkers such as the arteriolar to venular ratio. This biomarker provides valuable information about many pathological conditions such as diabetes, hypertension etc. Hence, in order to efficiently estimate the biomarkers, correct classification of retinal vessels extracted from digital images, into arterioles and venules is an important research problem. This paper presents an unsupervised retinal vessel classification approach which utilises the multiscale self-quotient filtering, to pre-process the input image before extracting the discriminating features. Thereafter the squared-loss mutual information clustering method is used for the unsupervised classification of retinal vessels. The proposed vessel classification method was evaluated on the publicly available DRIVE and INSPIRE-AVR databases. The proposed unclassified framework resulted in 93.2 and 88.9% classification rate in zone B for the DRIVE and the INSPIRE-AVR dataset respectively. The proposed method outperformed other tested methods available in the literature. Retinal vessel classification, in an unsupervised setting is a challenging task. The present framework provided high classification rate and therefore holds a great potential to aid computer aided diagnosis and biomarker research.

Keywords: Retina, Fundus images, Vessel classification, Arterioles, Venules, Illumination correction, Multiscale self-quotient filtering, Squared-loss mutual information clustering

Introduction

In the retina, blood vessels can be directly visualised non-invasively in-vivo, and hence it serves as a “window” to cardiovascular and neurovascular complications [1–4]. A number of systemic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease not only affect the retina (through diabetic retinopathy and hypertensive retinopathy, respectively) but they are also the main causes of morbidity and mortality in economically developed nations, leading to thousands of premature deaths per year [5–8]. In order to reduce the burden associated with these devastating conditions, there is a need to predict who is at risk or to spot the early stages of disease and target clinical interventions. Thus, the identification of discriminatory biomarkers is highly prized. Developments in retinal image processing and automated diagnostic systems open up the possibility for retinal imaging to be used in the large-scale screening programmes to detect early onset of otherwise debilitating conditions, with substantial resource savings and significant impact on health care [3].

A fundamental requirement of the retinal biomarker research is, an access to the large image datasets to achieve sufficient power and significance when ascertaining associations between the retinal measures and the clinical characterisation of disease. In addition, an essential part of any computerised systems for retinal vasculature characterisation in the fundus camera images is an automatic method for classifying vessels into arterioles and venules. This enables the extraction of useful diagnostic indicators or disease biomarkers such as the arteriolar to venular ratio (AVR), which is a well-established predictor of stroke and other cardiovascular events [9–11]. It is, therefore essential to extract biomarkers accurately which depends on many factors including the image quality.

Most of the classification algorithms depend on the discriminative power of the features extracted from the images in the dataset. To discriminate between retinal vessel classes, it is generally assumed that arterioles and venules are distinguishable based on different structural and colour features [7, 12] such as, (a) arterioles and venules usually alternate near the optic disc (OD) before branching out onto the surface of the fundus, (b) arterioles present more frequently with a central light reflex (i.e. the bright strip commonly seen in the centre of a vessel), (c) arterioles are usually brighter than venules as they contain oxygenated hemoglobin, which has higher reflectance in specific wave-lengths, than deoxygenated hemoglobin contained in venules.

In general, the alternating pattern of arterioles and venules is not always a valid discriminative feature because of branching. Moreover, the central light reflex often vanishes due to insufficient image quality or increasing age of subjects [12]. Also, the central light reflex can sometimes be present in veins, and in such cases, it becomes difficult to classify vessels using this feature.

Various methods for retinal vessel classification have been developed based on combination of different colour and geometric features. However, the poor quality images not only affects the performance of automatic image analysis system but also impedes the disease detection, which further impacts the patient treatment and care. Approximately of retinal images can not be analysed clinically because of inadequate image quality [13, 14]. Hence, pre-processing of images before characterisation play an important role in retinal images analysis.

This paper presents an unsupervised retinal arterioles venules (a–v) classification framework using the squared-loss mutual information clustering (SMIC) method. In this paper, we propose a multiscale self-quotient image (MSQ) [15] filtering method to pre-process the image prior to unsupervised retinal vessel classification. This new proposed framework uses four discriminating features extracted from background corrected red and green channel of the RGB image. The classification results obtained with proposed filtering method is compared with four different illumination correction methods—Multiscale weberface (MSW) [16], Tan and Triggs normalization technique [17], Discrete cosine transform based (DCT) photometric normalization technique [18] and Difference of Gaussian (DoG) [19].

The paper is structured as follows: Background literature is presented in Sect. 2. Section 3 gives the detail of the dataset used for this study. Section 4 provides the methodology behind the proposed vessel classification. Section 5 presents the results obtained, which are then discussed in Sect. 6 and followed by conclusions in Sect. 7.

Background

In the literature, a vast variety of approaches and frameworks based on different discriminative features, pre-processing techniques utilising different supervised as well as unsupervised classification algorithms have been proposed to identify different vessel types [12, 20–28].

Grisan et al. proposed a method to normalise luminosity and contrast before applying their vessel classification framework [20, 29]. They performed vessel classification in different sectors using fuzzy C-Mean clustering technique on 443 vessels from 35 images, and reported correct classification.

Saez et al. [22] performed quadrant-wise vessel classification using pixel-based and profile-based features constructed using red, green, hue and lightness colour components of the RGB and HSL colour space. The vessel classification was performed using k-means clustering on 58 images obtained from hypertensive subject between two concentric circumferences around the OD. The quadrants were rotated in steps of in order to include at least one vein and one artery in each quadrant to cluster the data. This system resulted in classification rates of 87 and using two different methods [30]. However, the classification approach of [20, 22] has a drawback, that it imposes a condition to have at least one vein and one artery per quadrant. Moreover, basic k-means clustering approach is sensitive to initialisation and therefore, can easily get stuck at a local minima.

Kondermann et al. [12], on the other hand, estimated the background of the image as a 2-dimensional spline and then subtracted that spline from the image in order to produces the final enhanced image. They used SVM and a neural network (NN) classifier for vessel classification. They showed that the performance of both NN and SVMs was extremely good on hand-segmented data, but the results deteriorated by on automatically segmented images of their own dataset. They used supervised approach which require large volumes of clinical annotations (i.e. manual labelling of vessels into venules and arterioles) to generate the requisite training data and this may not be easy to source.

In [31], authors performed the comparative study using different illumination correction (the dividing method using the median filter to estimate background, quotient based and homomorphic filtering) and contrast enhancement techniques such as the contrast limited adaptive histogram equalisation technique (CLAHE) and the polynomial transformation operator (PTO) on colour retinal images, in order to find the best technique for optimum image enhancement [31]. The performance of illumination correction techniques were evaluated by calculating the coefficients of variation. Furthermore, in order to grade the performance of contrast enhancement techniques, the performance measure such as sensitivity and specificity were evaluated from vessel segmentation. CLAHE was reported to have higher sensitivity than the PTO as a contrast enhancement technique for vessel segmentation purpose but no such comparison was reported for the retinal vessel classification problem.

In context of this paper, in Table 1, we report some important contributions from the available literature, proposing different retinal vessel classification approaches utilising discriminative features on the DRIVE (Digital Retinal Image for Vessel Extraction) and the INSPIRE-AVR (Iowa Normative Set for Processing Images of the Retina) dataset.

Table 1.

Summary of literature review on retinal a–v classification on the DRIVE and the INSPIRE-AVR dataset

| Author [Reference] | Method | Feature used | Dataset/zone/no. of Images (Im) or vessels (ves.) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirsharif et al. [24] | Classifiers: Kmeans, fuzzy clustering, & | and profile based features from HSL & LAB color spaces. | DRIVE & own/zone B/ 40 Im & 13 Im respt. | 90.2 & 88.2% respt. |

| Niemeijer et al. [25] | Classifiers: , , , , & wrapper based | 24 features from centreline pixel | DRIVE/whole Im/20 Im | Best result: kNN ROC: 0.88 |

| Niemeijer et al. [32] | Classifiers: , , , , : & wrapper based | 27 features from centreline pixel. | INSPIRE-AVR/zone B/20 Im | Best result:LDA ROC: 0.84 |

| Muramatsu et al. [26] | LDA classifier & leave-1-out method. | 6 features from R,G & B | DRIVE/zone B/160 ves. | 92.8% |

| Dashtbozorg et al. [27] | Classifier: , & , : | Structural information with 30 features from RGB & HSL colour space. | INSPIRE-AVR, DRIVE & VICAVR/whole Im/40, 20 & 58 Im respt. | Best result: LDA, 85.9, 87.4 & 89.8% respt. |

| Xu et al. [28] | with leave-1-out | colour, profile & texture features | DRIVE/whole Im/20 Im | Accuracy: 0.923 |

LDA Linear discriminant analysis, QDA quadratic discriminant analysis, SVM support vector machine, kNN k-nearest neighbors, ROI region of interest, FS feature selection, FFS forward feature selection, SFFM sequential forward floating method

Material

The proposed vessel classification method was evaluated on two publicly available databases namely the DRIVE and the INSPIRE-AVR.

DRIVE: It contains 40 colour fundus camera images [33]. The set of 40 images has been divided into a training and a test set, both containing 20 images each. The retinal photographs were obtained from a diabetic retinopathy screening program in the Netherlands and were acquired using a Cannon CR5 non-mydriatic 3CCD camera with a field of view (FoV). The resolution of the images are pixels and for each image one mask image is provided in the database that delineates the FoV. In this study, 20 test images are used to test the performance of the proposed method. 171 vessels from 20 test images in zone B (an annulus 0.5 to 1 OD diameter from the OD boundary) were extracted,

INSPIRE-AVR: This dataset contains 40 colour fundus camera images [32]. Details pertaining to image acquisition (i.e. camera system, FoV) are not reported in [32]. Vessel classification was performed on 483 vessels extracted from zone B of images of resolution pixels to validate the performance of the proposed method.

The images were labelled by the author (DR) to generate the ground truth by manually labelling vessels as arteriole or venule. Author was individually and independently trained by experienced clinicians in the identification of the retinal vessel type and has 5 years experience in retinal imaging and analysis.

Methodology

In the computerised retinal vessel classification process, first the red and green channel of RGB image were pre-processed to compensate for non-uniform background illumination (see Sect. 4.1). Thereafter, features were calculated around the centreline pixels (see Sects. 4.2 and 4.3) of the pre-processed image channels. Finally, based on the selected features, a quadrant pair-wise vessel clustering was performed using the SMIC method and an assignment of final labels (arterioles or venules) to each centreline pixel was done (see Sect. 4.4 for further details).

Image processing

During the image acquisition, images often get corrupted by noise, non-uniform illumination etc. Thus, in order to classify vessels in an efficient manner, it is very important to extract features from pre-processed image. The illumination correction algorithms are based on the illumination-reflectance model of the image formation. According to this model, the intensity at any pixel of an image is the product of the illumination of the scene and the reflectance of the object(s) in the scene, i.e.,

| 1 |

where I(x, y) denotes an image, R(x, y) is the scene reflectance and the L(x, y) stands for scene illumination (or luminance) at each of the spatial positions (x, y). Reflectance R arises from the properties of the scene objects whereas, illumination L results from the lighting conditions at the time of image capture and is related to the amount of illumination falling on the scene. In order to compensate for the non-uniform illumination, the main aim is to remove the illumination component and to keep only the reflectance component.

Multiscale self-quotient image

The main aim of the quotient image method is to deal with lighting changes and provides an invariant representation of images under different lighting conditions [34]. In self-quotient image (SQI) approach, an illumination invariant image representation Q(x, y) can be derived in the form of the quotient [15],

| 2 |

where, the denominator represents the smoothed version of the original input image I(x, y) and K(x, y) represents a smoothing kernel. Also,

| 3 |

where is the smoothed version of I. SQI is defined as the ratio of the input image and its smooth versions. The multi-scale form of the SQI technique, known as the MSQ, is obtained by a simple summation of self-quotient images derived with different filter scales. The MSQ method uses an anisotropic filter for the smoothing operation. In the MSQ method, the image I is smoothen by convolving it with each weighed anisotropic filter WG i.e.

| 4 |

where, is the convolution operator, G is the Gaussian smoothing kernel, W is the weight and N is the normalization factor. Multiscale self-quotient image between each input image I and its smoothing version is given by,

| 5 |

The division operation in the SQI may magnify high frequent noise especially in low signal noise ratio regions, such as in shadows. To reduce noise in Q, a nonlinear transformation function (such as Logarithm, Arctangent and Sigmoid etc.) can be used to transform Q into D, such that,

| 6 |

where T is a nonlinear transform. In our experiments, based on the results obtained from the initial analysis performed on a few randomly selected images, we have used the logarithmic transformation. Finally, summarising the nonlinearly transferred results as:

| 7 |

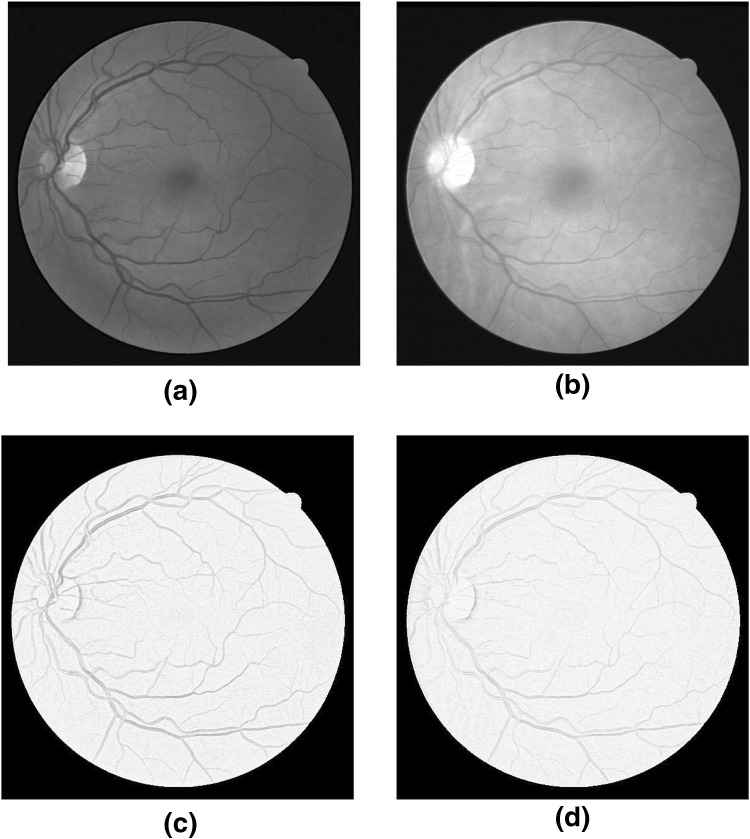

where, are the weights for each scale of filter. The green and red channels of RGB image were pre-processed to compensate for non-uniform background illumination. Figure 1 show the original green and red channel images alone with their MSQ filtered images.

Fig. 1.

(a) and (b) Original Green and Red channel images respectively ; (c) and (d) Illuminated corrected Green and Red channel respectively using the MSQ method

Centreline pixels detection

In order to extract the vessel centreline pixels, green channel of an image was used. First the cross-sectional intensity profiles, 5 pixel apart, on the vessel were found between manually marked start and end points.

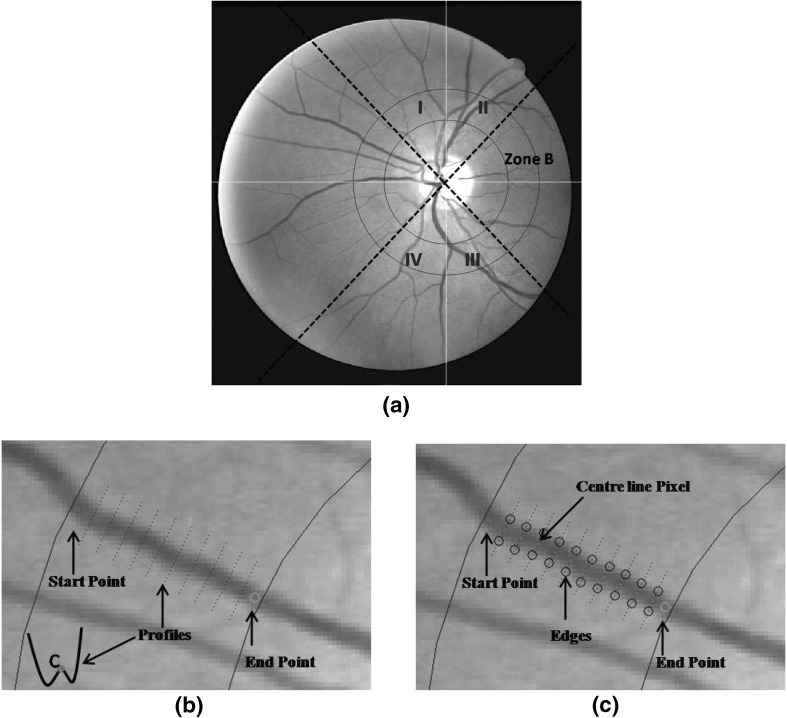

To do this, first the two points, start (S) and end (E), were marked manually on the vessels between which the vessel needs to be tracked (see Fig. 2(b)). Then the vector defining the direction from S to E, , was computed as , where and , with as the Euclidean distance between S and E. The angle ), where and are differences between x and y coordinates of points E and S. Then co-ordinates of the new point , 5 pixels ahead of S were calculated as,

| 8 |

At , the intensity profile across the vessel axis (and which resembles an inverted Gaussian; see Fig. 2(b) which shows an example) was obtained. Point C, marked red on the intensity profile (see Fig. 2(b)), give the approximate centre of the vessel and was found by locating and averaging 2 local minima on profile. Then, the next , was calculated (using Eq. 8) five pixels ahead of point C with vector direction . This procedure continues until end point E was reached, i.e. cross-sectional intensity profiles were found at every 5th pixel between S and E (blue doted straight lines in Fig. 2(b)). Then the Canny edge detector [35] was applied to each of these intensity profiles, to locate vessel edges (marked as black circles in Fig. 2(c)).

Fig. 2.

(a) Zone B (0.5 to 1 disc diameter from the optic disc margin surrounding the OD) is between two blue circular lines. While solid line, passing through OD centre, divide the image into four quadrants - I, II, III and IV, whereas, black dashed lines signifies the rotated quadrants co-ordinates i.e. when normal quadrants co-ordinates (denoted by white lines) rotated by , (b) Profiles between start (red marked) and end (green marked) points, (c) Extraction of edges (marked as black circles) and centreline pixel (marked pink) on each of the profile using canny edge detector. (Colour figure online)

In canny edge detection, the convolution with a Gaussian derivative kernel produces maxima (or minima) at step edges. We used multi resolution edge detection i.e. the edges were detected at multiple scales, starting at a coarse level to suppress noise, and ending at a fine level in order to improve accuracy. If detector outputs two edges then it represents the two edge points of the vessel. Whereas, when the canny edge detector gave more than two edge points, such as in presence of central reflex (is high reflectance strip in the centre of vessels), then the two extreme edge points (on opposite side of each other) were taken as vessel edges.

Finally the centreline pixels (marked as pink dots in Fig. 2(c)) were located as the midpoint of pair of edge points [36]. The distance between pair of edges was also stored as a vessel width. The centreline pixels were extracted from vessels in each quadrant. See Fig. 2(a) where white solid lines passing through OD centre divides the image into four quadrants - I, II, III and IV.

Features extraction

After finding the centreline pixels in each quadrant, four colour features: mean of red—MR, mean of green–MG, variance of red—VR and contrast of vessels w.r.t. background, were extracted. MR, MG and VR were extracted by sampling inside the vessels in the corrected channels using a circular neighbourhood around each centreline pixel, with diameter 60% of the mean vessel diameter. Whereas, the contrast feature was extracted from the corrected green channel.

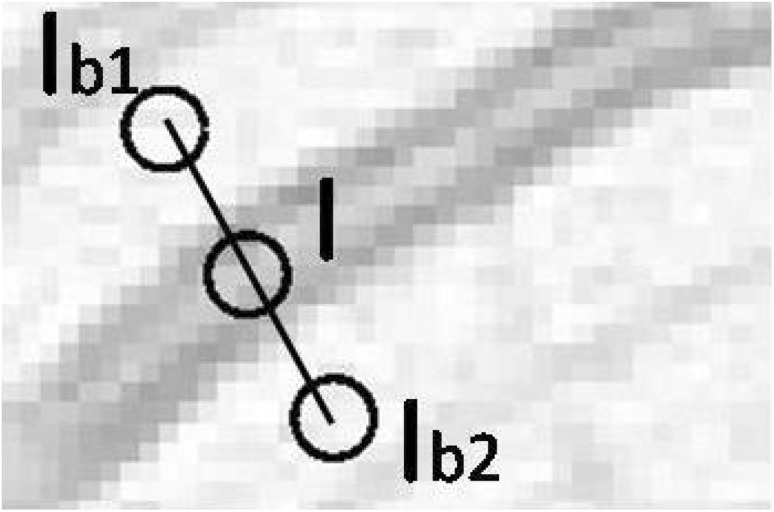

To do this, for each centreline pixel, a profile of length 2.5 times the width of the vessel was drawn. At each end of the profile, mean intensity and , from two circular ROI’s (whose diameters were 60% of the mean vessel diameter, and a centre as the end point of profile) were obtained as shown in Fig. 3. The average of these two intensities, , was calculated and this represented the background intensity. The mean intensity I from a circular neighbourhood around the centreline pixel (with diameter 60% of the mean vessel diameter) was extracted as the vessel intensity. The contrast feature, C, was then calculated as,

| 9 |

Fig. 3.

Extracting contrast features w.r.t. retinal background. I is the mean intensity extracted from circular ROI inside the vessels while and are the mean intensity extracted from circular ROI from the vessel background on either side of the vessel

Vessel classification

After feature extraction, each of the centreline pixels belonging to vessels from pair of adjacent quadrant (i.e. from quadrant combinations (I, II), (II, III), (III, IV) and (IV, I) ) were classified using the SMIC method by utilizing the information from the extracted features. The centroid of two cluster is associated with a vector of four mean values representing the four features. In order to determine the a–v class, the two average values of green channel intensity, representing the centroids of two clusters were compared. The cluster with higher mean green channel intensity at its centroid was defined as arterial cluster and the other as venous cluster.

In this way, the SMIC classifies the pixels into 2 clusters: arterioles and venules and thus assigning one label to each centreline pixel. As each quadrant was considered twice (due to pairing) in the processing, therefore, total two labels were assigned to each pixel. Then the quadrant partitioning was rotated clockwise and the centreline pixels belonging to vessels from pair of adjacent rotated quadrant were classified again, generating two more labels per centreline pixel.

Finally, each centreline pixel has total four soft labels from a group of arteriole or venule. The hard label was then assigned to each of the centreline pixel based on maximum number of soft labels of each type. Thereafter, the vessels were assigned a status of an arteriole or venule based on the maximum number of hard labels of each kind to pixels belonging to a vessel. If the votes were tied then the vessel was marked unclassified [36].

Squared-loss mutual information clustering (SMIC)

The SMIC is an unsupervised method in which the mutual information between feature vectors and cluster assignments (arterioles and venules) is maximised. It involves only continuous optimisation of the model parameters and is therefore, easier to solve as compared to discrete optimisation of the cluster assignments. Also, this method gives a clustering solution analytically in a computationally efficient way via kernel eigenvalue decomposition [37].

Suppose d-dimensional independent identically distributed (i.i.d.) feature vectors of size n drawn independently from a distribution with density p(x),

| 10 |

The main aim of the method is to give cluster assignments to feature vectors , such that,

| 11 |

where c denotes the number of classes and it was assumed that c is known. The information-maximisation approach explained in [38, 39] was used to solve a clustering (i.e. unsupervised classification) problem by the authors of [37].

To do this the class-posterior probability p(y|x), was learned so that ’information’ between feature vector x and class label y was maximised. The squared-loss mutual information (SMI) between feature vector x and class label y is defined by,

| 12 |

where p(x, y) denotes the joint density of x and y, and p(y) is the marginal probability of y. SMI is the Pearson divergence [40] from p(x, y) to p(x)p(y) while the ordinary mutual information (MI) [41],

| 13 |

is the Kullback–Leibler divergence [42] from p(x, y) to p(x)p(y). The Pearson divergence and the Kullback–Leibler divergence both belong to the class of f-divergences [43, 44], and thus they share similar properties.

Result

To test the overall classification accuracy of the system, following performance parameters were evaluated separately for arterioles (a) and venules (v).

-

Classification accuracy

.

Sensitivity ,

Specificity ,

Positive predicted value ,

Negative predicted value ,

Positive likelihood ratio ,

Negative likelihood ratio ,

where, TP: True Positive, FP: False Positive, TN: True Negative and FN: False Negative. This is further defined as,

True (): When both the system and the observer identified a vessel as arteriole (or venule).

False (): When the system identified a vessel as arteriole (or venule) and the observer identified it as venule (or arteriole).

True (): When the observer identified a vessel as venule (or arteriole) and the system identified it as not arteriole (or venule)

False (): When the system did not identify a vessel as arteriole (or venule) and the observer identified it as arteriole (or venule).

Table 2 summarises the classification accuracy obtained with the SMIC (where CR is the classification rate and the UnC stands for the unclassified vessels) w.r.t ground truth, when different illumination correction methods were applied to images from the DRIVE dataset. Table 3 gives the performance measures, computed separately for arterioles and venules, for all images when illumination correction was performed using the MSQ method. Table 4 summarises the True Positive rate (TPR) and classification accuracy for all images in the DRIVE test set.

Table 2.

Results obtained after vessel classification using the SMIC after pre-processing using different methods

| MSQ (%) | Tan and Triggs (%) | DoG (%) | MSW (%) | DCT (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 93.2 | 86.3 | 91.1 | 80.6 | 82.7 |

| (UnC) | 5.8 | 10.5 | 8 | 6.4 | 12.3 |

CR and UnC stands for the classification rate (or accuracy) and the Unclassified vessels respectively

Table 3.

Table showing the performance measure w.r.t ground truth, for arterioles and venules separately, using DRIVE dataset when classification was performed using the SMIC method using features extracted from the MSQ filtered images

| Performance measure | arterioles | venules |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.939 | 0.924 |

| Specificity | 0.924 | 0.939 |

| Positive predicted value | 0.928 | 0.936 |

| Negative predicted value | 0.936 | 0.928 |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 12.36 | 15.15 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.066 | 0.081 |

Table 4.

Table showing classification accuracy and True Positive rate (TPR) for arterioles () as well as for venules () for individual test images from the DRIVE test dataset

| index | Accuracy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.90 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.75 |

| 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 6 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.9 |

| 7 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.88 |

| 8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 9 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.86 |

| 10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 11 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 12 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 13 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 14 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.80 |

| 15 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.87 |

| 16 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 17 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 18 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.88 |

| 19 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.78 |

The performance of the proposed method, utilising the MSQ illumination correction technique, was further validated on the INSPIRE-AVR dataset. For the INSPIRE-AVR dataset, the performance measures computed separately for arterioles and venules are given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Table showing the performance measure w.r.t ground truth, for arterioles and venules separately, using INSPIRE-AVR dataset when features were extracted from the MSQ filtered images followed by classification using the SMIC method

| Performance Measure | arterioles | venules |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.925 | 0.844 |

| Specificity | 0.844 | 0.925 |

| Positive predicted value | 0.878 | 0.903 |

| Negative predicted value | 0.903 | 0.878 |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 5.939 | 11.303 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.088 | 0.168 |

Discussion

Table 2 shows that the classification rate obtained with the MSQ method was higher and the unclassified vessels were lower than that obtained with other tested illumination correction method. As seen from Table 3, the sensitivity for arterioles and venules was 0.939 and 0.924 respectively. That is to say, the probability of an incorrect classification was 6.1 and for arterioles and venules respectively.

Positive predicted value (PPV) is defined as the probability of a vessel to be arterioles (or venules), when classification result is positive. Similarly, the negative predicted value (NPV) is defined as the probability of a vessel to be not arterioles (or venules), when classification result is negative. The PPV (precision) and NPV, for both arterioles and venules, are high (see Table 3).

The positive likelihood ratios (PLR) >10 and negative likelihood ratios (NLR) <0.1 is considered significant [45, 46]. A PLR of >10 is considered strongly positive, 2–5 moderately positive and 0.5–2 weekly positive. Similarly, NLR of <0.1 is considered as strongly negative, 0.2–0.5 as moderately negative [46]. Thus, a high PLR and a low NLR confirmed the high reliability of the system. Table 4 shows that out of 20 images 11 images have accuracy.

Furthermore, on the INSPIRE-AVR dataset, the classification rate and percentage of unclassified vessels using the MSQ method, were 88.9 and . respectively. As seen from Table 5, the sensitivity for arterioles and venules was 0.925 and 0.844 respectively i.e. the probability of an incorrect classification was 7.5 and for arterioles and venules respectively. Similarly for the INSPIRE-AVR dataset, Table 5 also shows a high PLR and a low NLR. Moreover, the PPV and the NPV for both arterioles and venules are also high, as observed from Table 5.

The proposed method outperforms the previous work in which 86.2 and classification rate was obtained from an unsupervised [47] and supervised [48] framework respectively on the DRIVE dataset. Similarly, the proposed system also performs better than the previous work, when tested on the INSPIRE-AVR dataset, in which classification rate was obtained from an unsupervised [47] framework. The performance of the proposed framework is also observed to be better than the other reported methods, which use the DRIVE and the INSPIRE-AVR images as their test set [24–28, 32]. It should be noted that the vessel classification systems used in [24–28] are supervised whereas, the proposed method is an unsupervised method.

Conclusion

Image quality can vary in a large image dataset, depending on the type of diagnosis being made and contributes to misclassification. Therefore, retinal artery and vein classification, in an unsupervised setting is a challenging task. Pre-processing plays important role in the retinal image analysis. The present framework, which combines the MSQ filtering with the SMIC approach provided high classification rate in zone B, therefore holds a great potential to aid computer aided diagnosis and biomarker research.

Although, here we utilised only four discriminant features and rotated the quadrants, so that each vessel is labelled several times which improves the chances of correct classification, in our future research, we are working on to design an automatic unsupervised classification system which selects dominant features from large feature bank prior to classification. Moreover, in-spite of high classification rate of present framework, the classification accuracy may differ with different datasets.

Additionally, choosing a different retinal zone, classifier, preprocessing approach, features and framework would likely impact on the classification performance. Further tests on different and larger datasets are needed to declare its suitability to support retinal vessel classification in biomarker research.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

D. Relan, Email: devanjali_relan@ed-alumni.net

R. Relan, Email: rishi.relan@vub.ac.be

References

- 1.Liew G, Wang JJ. Retinal vascular signs: a window to the heart? Revista Española de Cardiología. 2011;64(6):515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClintic BR, McClintic JI, Bisognano JD, Block RC. The relationship between retinal microvascular abnormalities and coronary heart disease: a review. Am J Med. 2010;123(4):374–e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Patton N, Aslam TM, MacGillivray T, Deary IJ, Dhillon B, Eikelboom RH, Yogesan K, Constable IJ. Retinal image analysis: concepts, applications and potential. Prog Retinal Eye Res. 2006;25(1):99–127. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dehghani A, Moin M-S, Saghafi M. Localization of the optic disc center in retinal images based on the harris corner detector. Biomed Eng Lett. 2012;2(3):198–206. doi: 10.1007/s13534-012-0072-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H, Hsu W, Lee ML, Wong TY. Automatic grading of retinal vessel caliber. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005;52(7):1352–1355. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.847402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BE, Tielsch JM, Hubbard L, Nieto FJ. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and their relationship with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46(1):59–80. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(01)00234-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abràmoff MD, Garvin MK, Sonka M. Retinal imaging and image analysis. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2010;3:169–208. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2010.2084567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Doornum S, Strickland G, Kawasaki R, Xie J, Wicks I P, Hodgson L a B, Wong T Y. Retinal vascular calibre is altered in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a biomarker of disease activity and cardiovascular risk? Rheumatology. 2011;50:939–943. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong TY, Knudtson MD, Klein R, Klein BE, Meuer SM, Hubbard LD. Computer-assisted measurement of retinal vessel diameters in the beaver dam eye study: methodology, correlation between eyes, and effect of refractive errors. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(6):1183–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikram MK, Witteman JC, Vingerling JR, Breteler MM, Hofman A, de Jong PT. Retinal vessel diameters and risk of hypertension. Hypertension. 2006;47(2):189–194. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000199104.61945.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung H, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Tan AG, Wong TY, Klein R, Hubbard LD, Mitchell P. Relationships between age, blood pressure, and retinal vessel diameters in an older population. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(7):2900–2904. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondermann C, Kondermann D, Yan M. Blood vessel classification into arteries and veins in retinal images. In: Medical imaging, International Society for Optics and Photonics; 2007. p. 651247.

- 13.Fleming AD, Philip S, Goatman KA, Olson JA, Sharp PF. Automated assessment of diabetic retinal image quality based on clarity and field definition. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(3):1120–1125. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teng T, Lefley M, Claremont D. Progress towards automated diabetic ocular screening: a review of image analysis and intelligent systems for diabetic retinopathy. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2002;40(1):2–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02347689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Li SZ, Wang Y. Face recognition under varying lighting conditions using self quotient image. In: Proceedings sixth IEEE international conference on automatic face and gesture recognition, 2004. IEEE; 2004. p. 819–24

- 16.Wang B, Li W, Yang W, Liao Q. Illumination normalization based on weber’s law with application to face recognition. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2011;18(8):462–465. doi: 10.1109/LSP.2011.2158998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan X, Triggs B. Enhanced local texture feature sets for face recognition under difficult lighting conditions. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2010;19(6):1635–1650. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2010.2042645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang YJ. Advances in face image analysis: techniques and technologies. In: IGI Global; 2010.

- 19.Štruc V, Pavešic N. Photometric normalization techniques for illumination invariance. In: Zhang Y-J, editor. Advances in face image analysis: techniques and technologies, chap. 15. 2011. p. 279–300

- 20.Grisan E, Ruggeri A. A divide et impera strategy for automatic classification of retinal vessels into arteries and veins. In: Proceedings of the 25th annual international conference of the IEEE on Engineering in medicine and biology society, 2003. IEEE;2003. vol. 1, p. 890–893.

- 21.Tramontan L, Grisan E, Ruggeri A. An improved system for the automatic estimation of the arteriolar-to-venular diameter ratio (avr) in retinal images. In: Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2008. EMBS 2008. 30th Annual International Conference of the IEEE, p. 3550–3553, IEEE, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Saez M, González-Vázquez S, González-Penedo M, Barceló MA, Pena-Seijo M, de Tuero GC, Pose-Reino A. Development of an automated system to classify retinal vessels into arteries and veins. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2012;108(1):367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi VS, Garvin MK, Reinhardt JM, Abramoff MD. Automated artery-venous classification of retinal blood vessels based on structural mapping method. Proc SPIE Med Imaging Comput Aided Diagn. 2012;8315:83150I. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirsharif Q, Tajeripour F, Pourreza H. Automated characterization of blood vessels as arteries and veins in retinal images. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2013;37(7):607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niemeijer M, van Ginneken B, Abràmoff MD. Automatic classification of retinal vessels into arteries and veins. In: SPIE medical imaging. International Society for Optics and Photonics;2009. p. 72601F–72601F

- 26.Muramatsu C, Hatanaka Y, Iwase T, Hara T, Fujita H. Automated selection of major arteries and veins for measurement of arteriolar-to-venular diameter ratio on retinal fundus images. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2011;35(6):472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dashtbozorg B, Mendonça AM, Campilho A. An automatic graph-based approach for artery/vein classification in retinal images. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2014;23(3):1073–1083. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2013.2263809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu X, Ding W, Abràmoff MD, Cao R. An improved arteriovenous classification method for the early diagnostics of various diseases in retinal image. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2017;141:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foracchia M, Grisan E, Ruggeri A. Luminosity and contrast normalization in retinal images. Med Image Anal. 2005;9(3):179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vazquez S, Cancela B, Barreira N, Penedo MG, Saez M. On the automatic computation of the arterio-venous ratio in retinal images: using minimal paths for the artery/vein classification. In: 2010 international conference on digital image computing: techniques and applications (DICTA). IEEE; 2010. p. 599–604

- 31.Rasta SH, Partovi ME, Seyedarabi H, Javadzadeh A. A comparative study on preprocessing techniques in diabetic retinopathy retinal images: Illumination correction and contrast enhancement. J Med Signals Sensors. 2015;5(1):40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niemeijer M, Xu X, Dumitrescu AV, Gupta P, van Ginneken B, Folk JC, Abramoff MD. Automated measurement of the arteriolar-to-venular width ratio in digital color fundus photographs. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2011;30(11):1941–1950. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2159619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staal J, Abràmoff MD, Niemeijer M, Viergever MA, Van Ginneken B. Ridge-based vessel segmentation in color images of the retina. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23(4):501–509. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2004.825627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shashua A, Riklin-Raviv T. The quotient image: class-based re-rendering and recognition with varying illuminations. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2001;23(2):129–139. doi: 10.1109/34.908964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canny J. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1986;6:679–698. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.1986.4767851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Relan D, MacGillivray T, Ballerini L, Trucco E. Retinal vessel classification: sorting arteries and veins. In: Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2013 35th annual international conference of the IEEE. IEEE; 2013. p. 7396–7399 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Sugiyama M, Niu G, Yamada M, Kimura M, Hachiya H. Information-maximization clustering based on squared-loss mutual information. Neural Comput. 2014;26(1):84–131. doi: 10.1162/NECO_a_00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agakov F, Barber D. Kernelized infomax clustering. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2006;18:17. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golub GH, Loan CFV. Matrix Computations. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson KX. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philos Mag Ser 5. 1900;50(302):157–175. doi: 10.1080/14786440009463897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cover TM, Thomas JA. Elements of information theory. New York: Wiley; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kullback S, Leibler RA. On information and sufficiency. Ann Math Stat. 1951;22(1):79–86. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177729694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ali SM, Silvey SD. A general class of coefficients of divergence of one distribution from another. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol). 1966;28(1):131–42.

- 44.Csiszár I. Information-type measures of difference of probability distributions and indirect observations. Studia Scientiarum Mathematicarum Hungarica. 1967;2:299–318. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Šimundić A-M. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. EJIFCC. 2009;19(4):203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta A, Chowdhury V, Khandelwal N. Diagnostic radiology: recent advances and applied physics in imaging. Aiims-mamc-pgi Imaging. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers, Medical Publishers Pvt. Limited; 2013.

- 47.Relan D, Ballerini L, Trucco E, MacGillivray T. Retinal vessel classification based on maximization of squared-loss mutual information. In: Singh R, Vatsa M, Majumdar A, Kumar A, editors. Machine intelligence and signal processing. Berlin: Springer; 2016. p. 77–84.

- 48.Relan D, MacGillivray T, Ballerini L, Trucco E. Automatic retinal vessel classification using a least square-support vector machine in vampire. In: 36th annual international conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE; 2014. p. 142–145 [DOI] [PubMed]