Abstract

Recently, considerable attention has been paid to the negative effects caused by the presence and constant increase in concentration of heavy metals in the environment, as well as to the determination of their content in human biological samples. In this paper, the concentration of chromium in samples of blood and internal organs collected at autopsy from 21 female and 39 male non-occupationally exposed subjects is presented. Elemental analysis was carried out by an electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometer after microwave-assisted acid digestion. Reference ranges of chromium in the blood, brain, stomach, liver, kidneys, lungs, and heart (wet weight) in the population of Southern Poland were found to be 0.11–16.4 ng/mL, 4.7–136 ng/g, 6.1–76.4 ng/g, 11–506 ng/g, 2.9–298 ng/g, 13–798 ng/g, and 3.6–320 ng/g, respectively.

Keywords: Chromium concentration, Blood, Human organs, ETAAS

Introduction

Chromium (Cr) is one of the heavy metals that is important for humans [1]. It is present in air, water, soil, and any living matter from natural and anthropogenic sources, with the largest release occurring from industrial (metallurgical, refractory, and chemical) sources.

The leading consumer of chromium materials, with ferrochromiums as the main components, is the stainless steel industry. In the refractory industry, chromium is mainly used in linings for high temperature industrial furnaces, while in the chemical industry, it is used primarily in pigments. Other applications include metal finishing, leather tanning, wood preservatives, catalysts, and miscellaneous applications, such as drilling mud, chemical manufacturing, textiles, toners for copying machines, magnetic tapes, and dietary supplements (for example chromium picolinate) [2, 3]. What is more, chromium alloys are also used in metal joint prostheses [2, 4, 5].

However, the general population is primarily exposed to this element by ingesting food [6]. Other routes of exposure like inhalation of ambient air, drinking water, or skin contact with certain consumer products or soils that contain chromium are of rather minor importance [2]. Chromium-rich food includes entrails, meat, mollusks, lobsters, vegetables, bran, whole wheat or rye bread, and unrefined sugar [1, 3].

The estimated safe daily dose of Cr(III) is 50 to 200 μg [3], while an adequate intake determined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Research Council (NRC, USA) is 20–45 μg Cr(III)/day for adolescents and adults [2].

After ingestion, Cr(III) is absorbed mainly in the small intestine, then transported through blood to the cells and relatively quickly absorbed by bones, also accumulating in the spleen, liver, and kidneys [7]. The IOM reported average total plasma chromium concentrations of 0.10–0.16 μg/L and an average urinary chromium excretion of 0.22 μg/L or 0.2 μg/day [2].

Despite the growing interest in speciation analysis of different biologically important chromium forms—Cr(III), which is recognized as a trace element and Cr(VI), which is considered to be toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic—determination of its total content in available biological materials (such as body fluids and tissues) is still of great importance to clinical and forensic toxicology. This is because the knowledge of total content allows us to determine so-called “reference values/ranges” (for non-exposed and non-poisoned people), which can later be used for comparative purposes (confirmation or exclusion of any metal compound poisoning), for exposure assessment (e.g., environmental or occupational), as well as in the diagnosis of certain medical conditions. It is considered that chromium in the lungs is a result of deposition from inhaled air, whereas chromium in food is the main source in other organs [6]. For example, Antilla et al. [8] found that the average lung tissue concentration of total chromium in smokers was 6.4 μg/g versus 2.2 μg/g in non-smokers. Concentrations of total chromium in biological material in fatal cases of poisonings with chromium compounds are significantly higher (stomach 6–34 μg/g, liver 42–320 μg/g, kidneys 33–220 μg/g, blood 11 μg/mL, urine 18–101 μg/mL) [9].

However, current data on the concentration of total chromium in the human body in non-exposed people are mostly limited to concentrations found in whole blood [10–23], serum [11–13, 16, 24, 25], urine [11, 13–15, 17, 19, 20, 22, 25–34], or hair [17, 19, 20, 35–38] from living subjects, as these are the most easily available samples. If there is any information on chromium determination in tissues and organs, it comes rather from earlier publications [36, 39–44]; one of the newest was written in 2010 by Goullé et al. [45]. That is why, in this study, an evaluation of total chromium content in the internal organs and blood of non-exposed and non-poisoned subjects from Southern Poland was carried out.

Material and Methods

Reagents and Instrumentation

Analytical grade reagents from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and deionized water (NANOpure Diamond, Barnstead, Dubuque, IA) were used in the analysis. Glass and polypropylene vessels were soaked for 24 h in 5% (v/v) nitric acid solution and rinsed before use with deionized water.

An Ethos 1 microwave digestion system (Milestone, Sorisole, Italy) equipped with Teflon high-pressure reaction vessels was used for the wet digestion of samples of investigated materials.

The determination of total chromium was performed by an electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometer (Solaar MQZe, Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA), with Zeeman background correction, at a wavelength of 357.9 nm (slit width of 0.7 nm), according to a previously optimized and validated four-step procedure [46]. The measured volume of the sample solution was 20 μL.

Material and Sample Preparation

The study was carried out on 60 autopsy cases performed routinely in the Department of Forensic Medicine of the Jagiellonian University Medical College in Kraków, after approval by the Bioethics Committee of the Jagiellonian University (reference number: KBET/102/B/2009). Biological material undergoing testing was taken from the deceased not environmentally and occupationally exposed to elevated levels of chromium after visual assessment by a forensic medical examiner. Sections of internal organs (weighing about 50–100 g) were removed with stainless steel scalpels, put into acid pre-washed polypropylene vials, and frozen at − 20 °C until analysis. Before the digestion procedure, the samples were partially thawed, and thick sections of the surrounding surface tissue, which could have been contaminated by dust and/or stainless steel material at an earlier stage, were cut off using an acid pre-washed plastic knife (similarly to the procedure described by Rahil-Khazen et al. [42]). Then the whole sample was homogenized, and approximately 1.5 mL of blood and 1.5 g of internal organs was subjected to digestion: samples of biological material were wet digested with nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide in a 5:1 volume ratio in a microwave system. A total of 414 samples of postmortem blood and sections of macroscopically normal internal organs (brain, stomach, liver, kidneys, heart, and lungs) obtained from 21 women and 39 men, aged 29–89 (56 ± 18) years and 24–88 (47 ± 13) years, respectively, were analyzed.

The determination of chromium was performed on two parallel samples of one kind of biological material (taken from one deceased person)—giving a total number of 828 analyzed samples. Each analytical result was calculated as the average of the two values determined for a pair of samples (for a single sample, chromium concentration was measured in triplicate). Values of chromium concentrations found in blood and internal organs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chromium concentration in blood and internal organs (number of samples, mean ± SD, median, range) in non-exposed population of Southern Poland [ng/g wet weight or ng/mL]—gender approach

| Material | Group | n | Mean ± SD | Median | Range* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Female | 19 | 4.51 ± 3.53 | 4.33 | 0.11 | 11.4 |

| Male | 37 | 4.67 ± 4.28 | 3.74 | 0.11 | 16.4 | |

| Total | 56 | 4.62 ± 4.01 | 3.85 | 0.11 | 16.4 | |

| Brain | Female | 19 | 56.3 ± 53.3 | 39.5 | 4.8 | 197 |

| Male | 36 | 34.3 ± 23.2 | 26.8 | 4.7 | 95.9 | |

| Total | 55 | 40.8 ± 33.4 | 29.6 | 4.7 | 136 | |

| Stomach | Female | 19 | 92.0 ± 88.3 | 44.7 | 6.1 | 313 |

| Male | 35 | 31.8 ± 16.4 | 27.7 | 11.6 | 76.4 | |

| Total | 47 | 32.6 ± 16.7 | 28.3 | 6.1 | 76.4 | |

| Liver | Female | 19 | 136 ± 81 | 123 | 23 | 334 |

| Male | 37 | 290 ± 367 | 162 | 11 | 1381 | |

| Total | 52 | 156 ± 124 | 122 | 11 | 506 | |

| Kidney | Female | 17 | 50.1 ± 21.0 | 52.9 | 19.8 | 82.3 |

| Male | 37 | 106 ± 92 | 68.5 | 2.9 | 371 | |

| Total | 54 | 85.2 ± 73.4 | 60.6 | 2.9 | 298 | |

| Lung | Female | 19 | 362 ± 338 | 285 | 44 | 1204 |

| Male | 32 | 271 ± 181 | 211 | 13 | 716 | |

| Total | 49 | 271 ± 189 | 207 | 13 | 798 | |

| Heart | Female | 21 | 103 ± 104 | 59.2 | 3.6 | 366 |

| Male | 37 | 84.5 ± 58.2 | 77.0 | 6.9 | 318 | |

| Total | 58 | 90.5 ± 74.9 | 70.4 | 3.6 | 320 | |

*Minimum and maximum values obtained (after the removal of the outliers identified by the Grubb’s test) among different group analyzed (female, male, total)

Statistical Analysis

The material undergoing testing was taken from individuals without any visible pathological changes in their bodies. However, during the study, in some samples of certain materials, chromium content was found to be extremely high in comparison to the mean value established for the whole group. Using Grubbs’ test for outliers, all these extreme results, possibly related to health, nutrition, or smoking habits (data to which we unfortunately did not have access), were rejected before statistical evaluation of the obtained data.

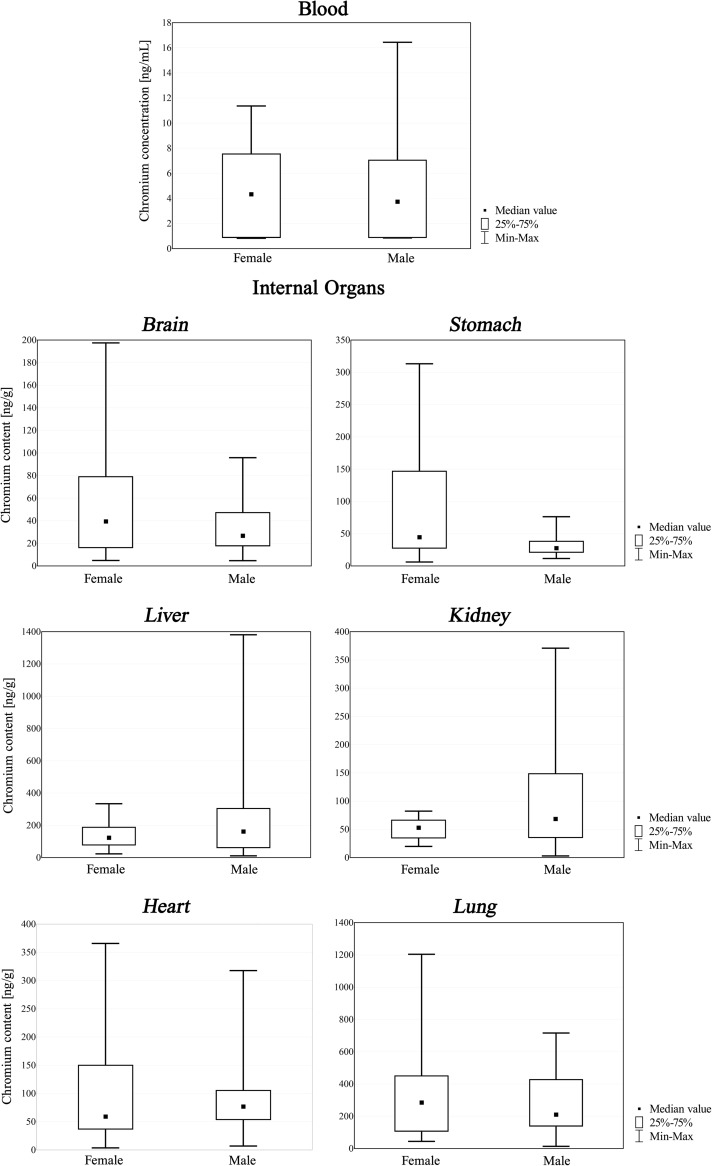

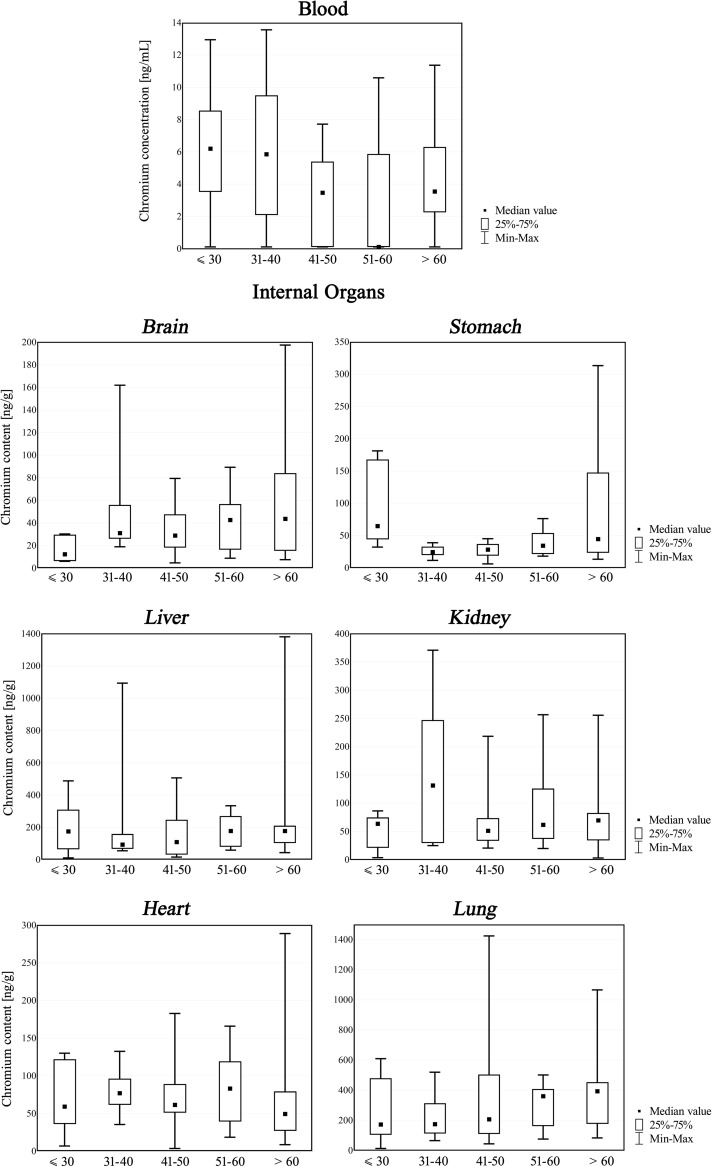

During statistical examination, Statistica 5.0 software was used. The Mann-Whitney U Test and ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis Test were applied to assess the relationship between chromium content in postmortem material and gender or age—the box and whisker plots are presented in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Chromium content in blood and internal organs [ng/mL or ng/g] of non-exposed population of Southern Poland: the Mann-Whitney U Test’s box and whisker plots drawn for gender

Fig. 2.

Chromium content in blood and internal organs [ng/mL or ng/g] of non-exposed population of Southern Poland: ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis Test’s box and whisker plots drawn for age-groups

Results and Discussion

In the analyses of body tissues, the highest chromium concentrations were determined in cumulative organs, such as the lungs and liver, in the ranges of 13.4–798 and 11–506 ng/g, respectively. The lowest chromium content was obtained for the stomach and brain, where the total averages did not exceed 50 ng/g. What is more, in 15 blood samples, the concentration of chromium was below the limit of quantification (LOQ, 0.22 ng/mL). For these samples, the results were replaced by a value of half the LOQ, when calculating the approximate mean chromium content.

Using the Mann-Whitney U Test, a statistically significant relationship between gender and chromium content (Table 1) was only revealed in the stomach (p = 0.006). It may be associated with different diets consumed by these two groups, as it is generally accepted that men eat more meat and bread (rich in chromium), while women consume more fruit, vegetables, and dairy products (with less chromium content) [3, 47–49].

As one can find in available literature, with the exception of the lungs, the concentration of chromium in all other organs decreases with age [6]. However in our study, such tendency could be seen only in blood samples; in other tissues, there was more or less visible increase in chromium content. What is more, when considering heart tissue, median values of chromium concentration obtained during the course of this study were practically on one level (between 50 and 80 ng/g) in all age groups, as well as in kidney tissue (close to 70 ng/g, apart from the group between 31 and 40 years where the value was about two times greater). ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis Test was used to assess whether there was a possible relationship between age and chromium concentration in particular tissue (Table 2). A statistically significant differences were again revealed only in the stomach samples (p = 0.01).

Table 2.

Chromium concentration in blood and internal organs (number of samples, mean ± SD, median, range) in non-exposed population of Southern Poland [ng/g wet weight or ng/mL]—age-group approach

| Material | Age-group | n | Mean ± SD | Median | Range* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | < 30 | 8 | 7.08 ± 3.41 | 7.58 | 0.11 | 12.9 |

| 31–40 | 10 | 5.85 ± 4.37 | 5.85 | 0.11 | 13.6 | |

| 41–50 | 14 | 3.95 ± 2.35 | 3.89 | 0.11 | 7.71 | |

| 51–60 | 11 | 3.35 ± 3.87 | 1.96 | 0.11 | 10.6 | |

| > 60 | 12 | 4.40 ± 3.63 | 3.54 | 0.11 | 11.4 | |

| Brain | < 30 | 6 | 18.2 ± 11.0 | 12.6 | 6.1 | 30.3 |

| 31–40 | 9 | 57.2 ± 53.3 | 31.1 | 18.9 | 162 | |

| 41–50 | 17 | 37.7 ± 20.5 | 36.5 | 4.7 | 79.4 | |

| 51–60 | 11 | 45.4 ± 25.9 | 45.2 | 8.8 | 89.3 | |

| > 60 | 12 | 59.7 ± 58.7 | 43.7 | 7.5 | 197 | |

| Stomach | < 30 | 7 | 87.2 ± 61.0 | 64.8 | 32.1 | 181 |

| 31–40 | 9 | 25.4 ± 9.2 | 24.4 | 11.6 | 38.9 | |

| 41–50 | 15 | 27.0 ± 11.3 | 28.3 | 6.1 | 45.2 | |

| 51–60 | 10 | 39.2 ± 20.1 | 34.4 | 18.1 | 76.4 | |

| > 60 | 13 | 93.0 ± 93.4 | 44.7 | 13.3 | 313 | |

| Liver | < 30 | 8 | 227 ± 162 | 219 | 10.9 | 488 |

| 31–40 | 9 | 289 ± 403 | 93 | 54.8 | 1094 | |

| 41–50 | 18 | 177 ± 153 | 130 | 15.8 | 506 | |

| 51–60 | 8 | 199 ± 99 | 193 | 58.6 | 334 | |

| > 60 | 13 | 317 ± 434 | 178 | 43.4 | 1381 | |

| Kidney | < 30 | 7 | 61.2 ± 22.5 | 66.0 | 21.1 | 86.2 |

| 31–40 | 10 | 149 ± 121 | 131 | 24.9 | 371 | |

| 41–50 | 18 | 78.7 ± 60.4 | 55.3 | 20.4 | 218 | |

| 51–60 | 10 | 97.0 ± 73.1 | 68.5 | 19.8 | 257 | |

| > 60 | 10 | 90.9 ± 87.4 | 69.6 | 2.9 | 256 | |

| Lung | < 30 | 8 | 267 ± 233 | 173 | 13.4 | 610 |

| 31–40 | 8 | 223 ± 152 | 175 | 65.2 | 519 | |

| 41–50 | 15 | 427 ± 488 | 207 | 43.9 | 1424 | |

| 51–60 | 9 | 301 ± 153 | 367 | 75.2 | 501 | |

| > 60 | 13 | 407 ± 297 | 393 | 83.0 | 1066 | |

| Heart | < 30 | 7 | 71.9 ± 45.6 | 59.2 | 6.89 | 130 |

| 31–40 | 9 | 80.2 ± 31.9 | 77.0 | 35.4 | 133 | |

| 41–50 | 16 | 75.0 ± 48.8 | 61.6 | 3.63 | 183 | |

| 51–60 | 10 | 82.0 ± 48.7 | 83.2 | 18.5 | 166 | |

| > 60 | 13 | 84.7 ± 90.9 | 49.4 | 8.64 | 289 | |

*Minimum and maximum values obtained (after the removal of the outliers identified by the Grubb’s test) among different group analyzed (female, male, total)

In Tables 3 and 4, levels of chromium in blood and internal organs determined by different authors are given.

Table 3.

Reference values of chromium in blood (number of samples, mean ± SD, range) found by various authors [ng/mL]

| Group | n | Mean ± SD | Median | Range | Country | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male and female | 23 | 0.18 ± 0.10 | Denmark | [12] | |||

| Male and female | 134 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.60 | UK | [15] | |

| Male and female | 519 | 0.23 ± 0,01 | 0.09 | 0.75 | Italy | [11] | |

| Adolescents | 200 | 0.25c | 0.23b | 0.27b | Belgium | [22] | |

| Male and female | 110 | 0.44 ± 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.12 | 1.07 | Italy | [16] |

| Male and female | 90 | 1.07 ± 0.68a | 0.96a | 0.04a | 2.37a | Pakistan | [23] |

| School children | 49 | 1.25 ± 0.74 | 1.10 | 0.40 | 4.63 | South Africa | [18] |

| Male and female | 106 | 4.10 | 0.55 | 0.33b | 0.87b | France | [21] |

| Male and female | 75 | 75.3 ± 7.6 | 63.3 | 87.1 | Pakistan | [17] | |

| Male 46–60 years |

43 | 60.5 ± 3.2 | 61.3 | 58.1 | 63.8 | Pakistan | [19] |

| Male 62–75 years |

37 | 58.9 ± 2.6 | 58.4 | 55.2 | 61.1 | Pakistan | [19] |

| Female 46–60 years |

47 | 59.2 ± 2.9 | 59.1 | 57.1 | 63.5 | Pakistan | [19] |

| Female 61–75 years |

39 | 54.2 ± 2.8 | 54.4 | 51.9 | 57.9 | Pakistan | [19] |

| Boys 6–10 years |

42 | 91.6 ± 8.2 | 83.9 | 109.3 | Pakistan | [20] | |

| Girls 6–10 years |

38 | 86.1 ± 7.2 | 79 | 93.2 | Pakistan | [20] | |

aThe conversion of g to mL has been made taking into account average density of blood—1.06 g/mL

bRange as 5–95th percentile

cGeometric mean

Table 4.

Reference values of chromium in internal organs (number of samples, median, mean ± SD, range) found by various authors [ng/g]

| Material | n | Mean ± SD | Median | Range | Country | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | 22 | 81 | 84 | 37 | 120 | Norway | [42] |

| 142 | 170 ± 120 | 150a | 190a | Korea | [43] | ||

| 20 | 51 | 20 | 140 | France | [45] | ||

| Liver | 30 | < 60 | < 60 | 1800 | Romania | [39] | |

| 41 | 100 | 80 | 40b | 210b | Italy | [36] | |

| 148 | 330 ± 250 | 290a | 370a | Korea | [43] | ||

| 5–11 | 270 ± 280 | Sweden | [44] | ||||

| 20 | 60 | 40 | 100 | France | [45] | ||

| Kidney | 30 | – | < 30 | < 30 | 120 | Romania | [39] |

| 41 | 60 | 60 | 30b | 120b | Italy | [36] | |

| 28c | 53 | 49 | 32 | 94 | Norway | [42] | |

| 28d | 50 | 52 | 21 | 94 | Norway | [42] | |

| 139 | 180 ± 140 | 150a | 200a | Korea | [43] | ||

| 5–11 | 513 ± 267 | Sweden | [44] | ||||

| 19 | 43 | 40 | 110 | France | [45] | ||

| Lung | 23 | 570 | 140 | 2190 | Germany | [41] | |

| 41 | 770 | 70b | 1490b | Italy | [36] | ||

| 140 | 410 ± 320 | 350 | 460 | Korea | [43] | ||

| 20 | < LOQ | France | [45] | ||||

| 18 | 61 | 57 | 41 | 103 | Norway | [42] | |

| Heart | 140 | 170 ± 130 | 150 | 190 | Korea | [43] | |

| 20 | < LOQ | France | [45] | ||||

a95% confidence interval

bRange as 5–95th percentile

cKidney cortex

dKidney medulla

When comparing results obtained in the course of this study with data published earlier, it can be stated that mean values of chromium concentration in blood and internal organs generally fell within the range of reference concentrations established by other authors, with a few exceptions. In blood samples, values obtained in normal adults given by Afridi et al. [17] and Kazi et al. [19] as well as in children (6–10 years old) reported by Shah et al. [20]—all from Pakistan—were definitely higher than those obtained by us and Cesbron et al. (among the French population) [21]. There have been no data concerning chromium content in the stomach provided by other authors. In the analysis of liver samples, chromium content in the range of 11–506 ng/g, with an average value of 156 ng/g, determined during this study was slightly higher than reported by Caroli et al. [36] and Goullé et al. [45] for non-occupationally exposed Italian and French subjects, respectively. Both Muramatsu and Parr [39] and Rahil-Khazen et al. [42] were not able to determine chromium in this medium. Among the results for the kidneys (in the range of 2.9–298 ng/g, with an average value of 85.2 ng/g) and the brain (in the range of 4.7–136 ng/g, with an average value of 40.8 ng/g), there were some higher ones; e.g., Engström et al. [44] estimated 513 ng/g in liver biopsy tissue supplied by Le Centre de Toxicologie du Québec (Canada) and Rahil-Khazen et al. [42]—81 ng/g in brain front lobe from autopsies performed in the Gade Institute, Department of Pathology and Department of Forensic Medicine (Norway). It is worth mentioning that compared to Yoo et al. [43], mean values of chromium concentration determined in this study were lower in all investigated matrices.

As mentioned in the Introduction section, one should bear in mind that the diversity between results obtained by us and other authors may be connected with the fact that different populations were studied in which many factors (such as health, age, gender, nutrition, and living and working environment) could have influenced the amount and distribution of chromium in the body. What is more, data obtained in this study, as well as the above mentioned results provided by other authors, refer to non-occupationally exposed, healthy people. Chromium content in blood and organs may vary in different pathologies and be higher when exposure to elevated levels occurs. For example, total chromium concentration ranges in the blood of atherosclerosis patients versus healthy donors, reported by Ilyas and Shah [23] were slightly higher (140–4210 and 40–2240 ng/g, respectively), while those in the blood of diabetes mellitus patients, as presented by Kazi et al., were lower (51.9–63.8 ng/mL in control group and 39.8–50.3 ng/mL in patients). When considering occupational exposure data provided by Danadevi et al. [50], Teraoka [51] are good examples. The first authors estimated that welders had significantly higher total chromium concentrations in blood when compared with controls (151.65 versus 17.86 ng/mL). The second reported that the highest concentration of chromium, from ten to a thousand times greater than the content stated for the control group (average 1.4 mg/g, dry weight), were found in lungs of two chromium plating (220 and 1400 mg/g) and three chromate refining (40, 58, and 110 mg/g) workers. A slightly higher values were also noticed in other investigated material, e.g., the liver, heart, spleen, and kidney.

Conclusions

On the basis of the results of analyses of chromium content in postmortem material obtained from 60 people in a Southern Polish population, it can be stated that there were no significant differences (except for the stomach) between male and female subjects, as well as that obtained data were generally consistent with other published findings, when taking into consideration that many factors may influence the final results. The obtained data may constitute a contribution to population-based studies on metal content in biological material, in particular autopsy material, and may be useful in the interpretation of the results of chemo-toxicological investigations.

Funding

This research was supported by the following research projects: Nos. NN404 189136 and NN404 010339, funded by The Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The study received ethical clearance (KBET/102/B/2009) from the Bioethics Committee of the Jagiellonian University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Danuta Dudek-Adamska, Email: dudekd@chemia.uj.edu.pl.

Teresa Lech, Email: tlech@ies.krakow.pl.

Tomasz Konopka, Email: tomasz.konopka@uj.edu.pl.

Paweł Kościelniak, Email: koscieln@chemia.uj.edu.pl.

References

- 1.Anderson RA. Chromium as an essential nutrient for humans. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1997;26:S35–S41. doi: 10.1006/rtph.1997.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological profile for chromium. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bielicka A, Bojanowska I, Wiśniewski A. Two faces of chromium—pollutant and bioelement (review) Pol J Environ Stud. 2005;14:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, Tomlinson MJ, Gavrilovic J, Black J, Peoch M. Dissemination of wear particles to the liver, spleen, and abdominal lymph nodes of patients with hip or knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82-A:457–477. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeiner M, Zenz P, Lintner F, Schuster E, Schwägerl W, Steffan I. Influence on elemental status by hip-endoprostheses. Microchem J. 2007;85:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2006.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langård S, Costa M (2007) Chromium. In: G.F. Nordberg, B.A. Fowler, M. Nordberg, L. Friberg (eds) Handbook on the toxicology of metals, 3rd edn. Elsevier ISBN pp 487–510

- 7.Pechova A., Pavlata L. Chromium as an essential nutrient: a review. Veterinární Medicína. 2008;52(No. 1):1–18. doi: 10.17221/2010-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antilla S, Kokkonen P, Pääkö P, Rainio P, Kalliomäki P-L, Pallon J, Malmqvist K, Pakarrinen P, Näntö V, Sutinen S. High concentrations of chromium in lung tissues from lung cancer patients. Cancer. 1989;63:467–473. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890201)63:3<467::AID-CNCR2820630313>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lech T. Acute and fatal poisonings with chromium compounds. Arch Med Sad Krym (Polish) 1987;37:115–120. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herring WB, Leavell BS, Paixo LM, Yoe JH. Trace metals in human plasma and red blood cells. A study of magnesium, chromium, nickel, copper and zinc. I. Observations of normal subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1960;8:846–854. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/6.2.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minoia C, Sabbioni E, Apostoli P, Pietra R, Pozzoli L, Gallorini M, Nicolaou G, Alessio L, Capodaglio E. Trace element reference values in tissues from inhabitants of the European community. I. A study of 46 elements in urine, blood and serum of Italian subjects. Sci Total Environ. 1990;95:89–105. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(90)90055-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen JM, Holst E, Bonde JP, Knudsen L. Determination of chromium in blood and serum: evaluation of quality control procedures and estimation of reference values in Danish subjects. Sci Total Environ. 1993;132:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(93)90258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poulsen OM, Christensen JM, Sabbioni E, Van der Venne MT. Trace element reference values in tissues from inhabitants of the European Community. V. Review of trace elements in blood, serum and urine and critical evaluation of reference values for the Danish population. Sci Total Environ. 1994;141:197–215. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristiansen J, Christensen JM, Iversen BS, Sabbioni E. Toxic trace element reference levels in blood and urine: influence of gender and lifestyle factors. Sci Total Environ. 1997;204:147–160. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(97)00155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White MA, Sabbioni E. Trace element reference values in tissues from inhabitants of the European Union. X. A study of 13 elements in blood and urine of a United Kingdom population. Sci Total Environ. 1998;216:253–270. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alimonti A, Bocca B, Mannella E, Petrucci F, Zennaro F, Cotichini R, D'Ippolito C, Agresti A, Caimi S, Forte G. Assessment of reference values for selected elements in a healthy urban population. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2005;41:181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afridi HI, Kazi TG, Jamali MK, Kazi GH, Arain MB, Jalbani N, Shar GQ, Sarfaraz RA. Evaluation of toxic metals in biological samples (scalp hair, blood and urine) of steel mill workers by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry. Toxicol Ind Health. 2006;22:381–393. doi: 10.1177/0748233706073420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazzi A, Nriagu JO, Linder AM. Determination of toxic and essential elements in children’s blood with inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. J Environ Monit. 2008;10:1226–1232. doi: 10.1039/b809465a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazi TG, Afridi HI, Kazi N, Jamali MK, Arain MB, Jalbani N, Kandhro GA. Copper, chromium, manganese, iron, nickel, and zinc levels in biological samples of diabetes mellitus patients. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2008;122:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s12011-007-8062-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah F, Kazi TG, Afridi HI, Kazi N, Baig JA, Shah AQ, Khan S, Kolachi NF, Wadhwa SK. Evaluation of status of trace and toxic metals in biological samples (scalp hair, blood, and urine) of normal and anemic children of two age groups. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;141:131–149. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cesbron A, Saussereau E, Mahieu L, Couland I, Guerbet M, Goullé JP. Metallic profile of whole blood and plasma in a series of 106 healthy volunteers. J Anal Toxicol. 2013;37:401–405. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkt046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baeyens W, Vrijens J, Gao Y, Croes K, Schoeters G, Den Hond E, Sioen I, Bruckers L, Nawrot T, Nelen V, Van Den Mieroop E, Morrens B, Loots I, Van Larebeke N, Leermakers M. Trace metals in blood and urine of newborn/mother pairs, adolescents and adults of the Flemish population (2007-2011) Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014;217:878–890. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilyas A, Shah MH. Multivariate statistical evaluation of trace metal levels in the blood of atherosclerosis patients in comparison with healthy subjects. Heliyon. 2016;2:e00054. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2015.e00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahil-Khazen R, Henriksen H, Bolann BJ, Ulvik RJ. Validation of inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry technique (ICP-AES) for multi-element analysis of trace elements in human serum. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2000;60:677–686. doi: 10.1080/00365510050216402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Todorovska N, Karadjova I, Arpadjan S, Stafilov T. On chromium direct ETAAS determination in serum and urine. CEJC. 2007;5:230–238. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidson IW, Secrest WL. Determination of chromium in biological materials by atomic absorption spectrometry using a graphite furnace atomizer. Anal Chem. 1972;44:1808–1813. doi: 10.1021/ac60319a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quináia SP, Nóbrega JA. A critical evaluation of the graphite furnace conditions for the direct determination of chromium in urine. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 1999;364:333–337. doi: 10.1007/s002160051345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campillo N, Viñas P, López-García I, Hernández-Córdoba M. Determination of molybdenum, chromium and aluminium in human urine by electrothermal atomic ranges based on U.S. patient population and literature reference intervals absorption spectrometry using fast-programme methodology. Talanta. 1999;48:905–912. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(98)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komaromy-Hiller G, Ash KO, Costa R, Howerton K. Comparison of representative for urinary trace elements. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;296:71–90. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(00)00205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin TW, Huang SD. Direct and simultaneous determination of copper, chromium, aluminum, and manganese in urine with a multielement graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2001;73:4319–4325. doi: 10.1021/ac010319h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliveira PV, Oliveira E. Multielement electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry: a study on direct and simultaneous determination of chromium and manganese in urine. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 2001;371:909–914. doi: 10.1007/s002160101060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arancibia V, Valderrama M, Silva K, Tapia T. Determination of chromium in urine samples by complexation–supercritical fluid extraction and liquid or gas chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 2003;785:303–309. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00924-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeiner M, Ovari M, Zaray G, Steffan I. Selected urinary metal reference concentrations of the Viennese population - urinary metal reference values (Vienna) J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2006;20:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maria MF, Hossu AM, Negrea P, Iovi A. GFAAS method for determination of total chromium in urine. OUAC. 2009;20:80–82. [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiPietro ES, Phillips DL, Paschal DC, Neese JW. Determination of trace elements in human hair. Reference intervals for 28 elements in nonoccupationally exposed adults in the US and effects of hair treatments. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1989;22:83–100. doi: 10.1007/BF02917419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caroli S, Alimonti A, Femmine PD, Petrucci F, Senofonte O, Violante N, Menditto A, Morisi G, Menotti A, Falconieri P. Role of inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry in the assessment of reference values for trace elements in biological matrices. J Anal At Spectrom. 1992;7:859–864. doi: 10.1039/ja9920700859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gellein K, Lierhagen S, Brevik PS, Teigen M, Kaur P, Singh T, Flaten TP, Syversen T. Trace element profiles in single strands of human hair determined by HR-ICP-MS. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2008;123:250–260. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mikulewicz M, Chojnacka K, Gedrange T, Górecki H. Reference values of elements in human hair: a systematic review. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2013;36:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muramatsu Y, Parr RM. Concentrations of some trace elements in hair, liver and kidney from autopsy subjects—relationship between hair and internal organs. Sci Total Environ. 1988;76:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(88)90280-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aalbers TG, Houtman JP, Makkink B. Trace-element concentrations in human autopsy tissue. Clin Chem. 1987;33:2057–2064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kollmeier H, Seemann JW, Rothe G, Müller KM, Wittig P. Age, sex, and region adjusted concentrations of chromium and nickel in lung tissue. Br J Ind Med. 1990;47:682–687. doi: 10.1136/oem.47.10.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahil-Khazen R, Bolann BJ, Myking A, Ulvik RJ. Multi-element analysis of trace element levels in human autopsy tissues by using inductively coupled atomic emission spectrometry technique (ICP-AES) J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2002;16:15–25. doi: 10.1016/S0946-672X(02)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoo YC, Lee SK, Yang JY, In SW, Kim KW, Chung KH, Chung MG, Choung SY. Organ distribution of heavy metals in autopsy material from normal Korean. J Health Sci. 2002;48:186–194. doi: 10.1248/jhs.48.186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engström E, Stenberg A, Senioukh S, Edelbro R, Baxter DC, Rodushkin I. Multi-elemental characterization of soft biological tissues by inductively coupled plasma–sector field mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2004;521:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2004.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goullé JP, Mahieu L, Anagnostides JG, Bouige D, Saussereau E, Guerbet M, Lacroix C. Profil métallique tissulaire par ICP-MS chez des sujets décédés. Ann Toxicol Anal (French) 2010;22:1–9. doi: 10.1051/ata/2010001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lech T, Dudek-Adamska D. Optimization and validation of a procedure for the determination of total chromium in postmortem material by ETAAS. J Anal Toxicol. 2013;37:97–101. doi: 10.1093/jat/bks097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bates CJ, Prentice A, Finch S. Gender differences in food and nutrient intakes and status indices from the National Diet and nutrition survey of people aged 65 years and over. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:694–699. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leblanc V, Bégin C, Hudon AM, Royer MM, Corneau L, Dodin S, Lemieux S. Gender differences in the long-term effects of a nutritional intervention program promoting the Mediterranean diet: changes in dietary intakes, eating behaviors, anthropometric and metabolic variables. Nutr J. 2014;13:107. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Metcalf PA, Scragg RR, Schaaf D, Dyall L, Black PN, Jackson R. Dietary intakes of European, Māori, Pacific and Asian adults living in Auckland: the diabetes, heart and health study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32:454–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danadevi K, Rozati R, Banu BS, Grover P. Genotoxic evaluation of welders occupationally exposed to chromium and nickel using the comet and micronucleus assays. Mutagenesis. 2004;19:35–41. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teraoka H. Distribution of 24 elements in the internal organs of normal males and the metallic Workers in Japan. Arch Environ Health. 1981;36:155–165. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1981.10667620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]