Abstract

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer are powerful and versatile techniques to quantify and describe molecular interactions. They are particularly well suited to the study of dynamic proteins and assemblies, as they can overcome some of the challenges that stymie more conventional ensemble approaches. In this chapter, we describe the application of these methods to study the interaction of tau with the molecular aggregation inducer, heparin, and the functional binding partner, soluble tubulin. Specifically, we outline the practical aspects of both techniques to characterize the critical first steps of tau aggregation and tau-mediated microtubule polymerization. The information gained from these measurements provides unique insight into tau function and its role in disease.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since its discovery in 1975 (Weingarten, Lockwood, Hwo, & Kirschner, 1975), tau has been extensively studied both for its role in critical cellular processes, as well as its contribution to neurodegeneration (Brunden, Trojanowski, & Lee, 2009; Morris, Maeda, Vossel, & Mucke, 2011; Wang & Mandelkow, 2016). Understanding tau function, how function is altered in disease and the relationship between loss of function and tau aggregation requires a description of relevant molecular mechanisms. There are numerous experimental challenges to achieving this goal, including tau’s intrinsically disordered structure (Cleveland, Hwo, & Kirschner, 1977; Schweers, Schonbrunn-Hanebeck, Marx, & Mandelkow, 1994), its propensity to aggregate (Chirita, Congdon, Yin, & Kuret, 2005; Friedhoff, Schneider, Mandelkow, & Mandelkow, 1998), and the dynamic nature of microtubule polymerization (Drechsel, Hyman, Cobb, & Kirschner, 1992; Trinczek, Biernat, Baumann, Mandelkow, & Mandelkow, 1995). To overcome these limitations, our lab applies single-molecule fluorescence techniques, namely fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) and single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) to characterize its aggregation prone structures (Elbaum-Garfinkle, Ramlall, & Rhoades, 2010; Elbaum-Garfinkle & Rhoades, 2012) and its binding to tubulin, an important aspect of microtubule polymerization (Elbaum-Garfinkle, Cobb, Compton, Li, & Rhoades, 2014; Li, Culver, & Rhoades, 2015; Melo et al., 2016). In this chapter, we describe our protocols and technical aspects of the application of FCS and smFRET to study tau and its interactions with binding partners.

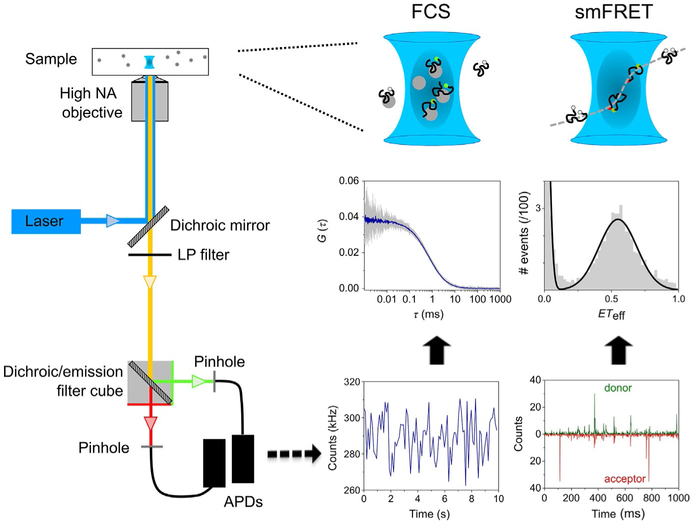

Both FCS and smFRET are increasingly applied to studies of protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions; protein conformation and dynamics; and protein function and aggregation (Chen & Rhoades, 2008; Haustein & Schwille, 2003; Schuler, Soranno, Hofmann, & Nettels, 2016). These techniques are similar in implementation and instrumentation; they often provide synergistic information about the molecules studied. Moreover, although more commonly used in vitro, both methods can be applied to measurements in living cells (Bacia, Kim, & Schwille, 2006; Konig et al., 2015; Machan & Wohland, 2014). FCS is a powerful technique to investigate a large variety of dynamic processes and to quantify biological interactions. It measures fluorescence intensity fluctuations of a small number of fluorescent molecules as they diffuse through a small observation volume (~1 fL) (Fig. 1). Any process that changes fluorescence can be detected by FCS (Hess, Huang, Heikal, & Webb, 2002; Rigler & Elson, 2001). For our purposes, we use single-color FCS to quantify the interactions between soluble tubulin and tau based on changes in the diffusion upon binding (Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015).

FIG. 1.

Overview of FCS and smFRET instrument and measurements. Left: Schematic of a typical confocal setup used in FCS or smFRET measurements. The laser is focused by a high NA objective lens to a diffraction-limited confocal volume. Emitted fluorescence is collected through the same objective, separated from the excitation light by a dichroic mirror and long-pass filter and finally focused onto the confocal pinhole. Center: FCS measures fluorescence intensity fluctuations over time of single-labeled molecules (at nM concentration) diffusing through the confocal volume. The signal is then processed using an autocorrelation algorithm to obtain the autocorrelation curves. Right: In smFRET measurements, each single donor–acceptor-labeled molecule produces burst of photons while it diffuses through the confocal volume in a timescale of a few milliseconds. The ETeff values are then calculated for each photon burst and plotted as a histogram.

smFRET is now widely used to probe conformational changes and dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids (Banerjee & Deniz, 2014; Chen & Rhoades, 2008; Murphy, Rasnik, Cheng, Lohman, & Ha, 2004; Schuler et al., 2016). It can provide unique insights into the conformations of large and dynamic proteins—such as tau—where higher resolution structural approaches cannot be applied (Elbaum-Garfinkle & Rhoades, 2012; Melo et al., 2016). FRET is a nonradiative transfer of energy from a donor fluorophore to an acceptor fluorophore that occurs through a dipole–dipole mechanism. The efficiency of transfer, ETeff, exhibits a strong dependence on the donor–acceptor distance as described by the Förster equation (Förster, 1948). When both donor and acceptor fluorophores are placed on the same molecule (intramolecular FRET), smFRET reports on protein conformational changes related to folding, binding, or activity (Banerjee & Deniz, 2014; Chen & Rhoades, 2008; Hohlbein & Kapanidis, 2016; Michalet, Weiss, & Jager, 2006; Schuler et al., 2016). Single-molecule applications of FRET include measurements of both immobilized and freely diffusing molecules (reviewed in Roy, Hohng, & Ha, 2008). We focus on the second type here, as it is the approach used for our studies of tau. In these measurements, Brownian diffusion results in the transit of the protein (~10–100pM) through an observation volume defined by a focused laser beam (as in FCS) (Fig. 1). The donor molecule is excited and photons from the donor and acceptor are collected and analyzed as described in our protocols later.

2. METHODS

2.1. TAU EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION

The protocol developed in our lab for the expression and purification of tau has been used for both full-length and truncated forms of the protein (Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2014, 2010; Elbaum-Garfinkle & Rhoades, 2012; Li et al., 2015; Melo et al., 2016). We cloned tau into a pET—HT plasmid with an N-terminal His-tag and a tobacco etch virus cleavage site. Expression and purification are performed as published previously (Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2014; Elbaum-Garfinkle & Rhoades, 2012; Melo et al., 2016), with nickel-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography steps. All chromatography is carried out at 4°C to minimize protein degradation. For site-specific labeling, QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis (Stratagene) is used to mutate endogenous cysteines (at residues 291 and 322 in the 2N4R tau isoform) to serines, as well as to introduce additional cysteines at desired sites.

2.2. LABELING TAU FOR smFRET MEASUREMENTS

The protocol described later for labeling tau with donor and acceptor fluorophores was developed to minimize the fraction of donor-only labeled protein that contributes to the ETeff=0 peak in smFRET histograms (Melo et al., 2016). Our most commonly used donor and acceptor fluorophores are Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594 maleimide, respectively. However, this protocol should be applicable to other maleimide fluorophore pairs with minimal adaptation.

1. Incubate freshly purified tau (~400–500 μL of at least 100 μM protein) with 1mM DTT for 30min at room temperature (RT).

2. During DTT incubation, couple two HiTrap 5-mL Desalting Columns (GE Life Sciences) and equilibrate with labeling buffer: 20mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50mM NaCl, 6M guanidine hydrochloride (GdmCl). Confirm pH > 7 and adjust if needed. The use of two coupled columns results in better separation of the protein from small molecules, such as DTT (this step) or fluorophores (step 7).

3. After DTT incubation, load the protein solution onto the coupled desalting columns using a 1mL syringe. The protein is eluted using 10mL of labeling buffer, collecting the elution in ~0.5mL fractions. Measure absorbance to identify and determine concentration of protein-containing fractions. This step both removes DTT, which interferes with maleimide fluorophore labeling, and exchanges the protein into the labeling buffer.

4. Transfer protein to a clean glass vial containing a small stir bar and add donor fluorophore to a final 0.5:1 dye:protein molar ratio. Protect from light and incubate for 2h at RT with stirring.

5. Add 5× molar excess of acceptor fluorophore. Protect from light and incubate with stirring overnight at 4°C. Labeling by this approach will result in tau with various combinations of donor and acceptor fluorophore at the labeling sites (see Note).

6. To purify the labeled protein from unreacted dye and remove GdmCl, first concentrate and buffer exchange the labeled protein into measurement buffer (20mM Tris, pH 7.4, and 50mM NaCl) using an Amicon Ultra 10K Concentrator (Millipore). This step removes a substantial fraction of the unreacted fluorophore and improves separation on the desalting columns.

7. During the incubation steps, equilibrate the coupled desalting columns into the measurement buffer by washing with ~100mL measurement buffer. Load the protein sample onto the coupled desalting columns and elute with 10mL of measurement buffer. The protein should start to elute after ~2.5mL (the labeled protein can be seen by eye). To avoid coelution of free dye, collect only the first ~0.5mL following the beginning of protein elution.

8. Owing to the low extinction coefficient of tau (7450M−1 cm−1 at 280nm for the 2N4R tau isoform), its concentration cannot be accurately determined by absorbance when extrinsic fluorophores (which also absorb at 280nm) are present. We use a modified Lowry assay (Bio—Rad) with unlabeled tau protein as a standard to determine the protein concentration and absorbance of the fluorophores to determine the labeling efficiency.

9. Aliquot the labeled tau into ~25 μL volumes and flash freeze with liquid nitrogen for storage at −80°C.

Notes

For reproducibility in the labeling reactions, we prepare dye aliquots of known concentration. To do so, 1mg of fluorophore is dissolved in 100 μL anhydrous DMSO (Invitrogen). For Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594, the final concentrations are 13.9 and 11mM, respectively. Aliquot (typically 5 or 10μL volumes) into Eppendorf tubes, evacuate gently with nitrogen for ~5s, cover the tubes with parafilm, and flash freeze in liquid nitrogen for storage at −80°C.

The fluorophores should be protected from light at all stages in the labeling reaction, for example, by covering with aluminum foil.

Unless additional purification steps are utilized during the labeling procedure (Schuler, Muller-Spath, Soranno, & Nettels, 2012), double labeling any protein through cysteine residues is expected to yield a mixture of (i) single- or double-labeled protein with donor (donor-only labeled protein) or acceptor (acceptor- only labeled protein) and (ii) double labeled with donor at position 1 and acceptor at position 2, as well as the reverse. The donor- and acceptor-only labeled proteins can be easily separated in analysis. In the first case, donor-only labeled protein contributes only to the ETeff = 0 peak ubiquitous to smFRET histograms (see Figs. 3 and 4). The acceptor-only labeled proteins do not contribute to the smFRET signal, as the acceptor is not directly excited. Our measurements suggest that tau is relatively insensitive to fluorophore position.

It is good practice to determine the fluorescence lifetime and anisotropy of each fluorophore at specific labeling position for accurate calculation of the Förster radius, and consequently the ETeff values (Schuler et al., 2012, 2016).

As an alternative to the approach described here, the use of a genetically encoded unnatural amino acid in combination with a single cysteine provides an orthogonal reactivity for precise site-specific labeling (Tyagi & Lemke, 2013).

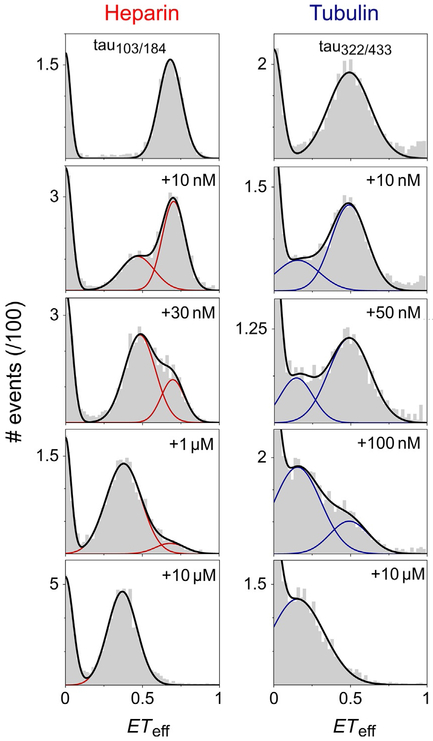

FIG. 3.

Titration of tau with heparin and tubulin by smFRET. Tau 2N4R is labeled at residues 103 and 184 (tau103/184) or residues 322 and 433 (tau322/433). Initially, in the absence of binding partners, two peaks are present in the ETeff histograms: ETeff=0 arises from imperfectly labeled molecules, as described in the text, while ETeff≠0 is ascribed to tau in solution. With increasing concentrations of heparin or tubulin, the growth of a second protein peak at lower ETeff—corresponding to tau bound to either partner—is concomitant with the progressive loss of the original solution peak. For both regions of tau probed in these measurements, binding results in an expansion of the region between the fluorophores, as seen by the decrease in ETeff relative to tau in buffer. The smFRET histograms were fit with multipeak Gaussian functions.

Adapted from Elbaum-Garfinkle S. and Rhoades E., Identification of an aggregation–prone structure of tau, Journal of the American Chemical Society 134, 2012, 16607–16613; Melo, A. M., Coraor, J., Alpha-Cobb, G., Elbaum-Garfinkle, S., Nath, A., & Rhoades, E. (2016). A functional role for intrinsic disorder in the tau–tubulin complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 14336–14341.

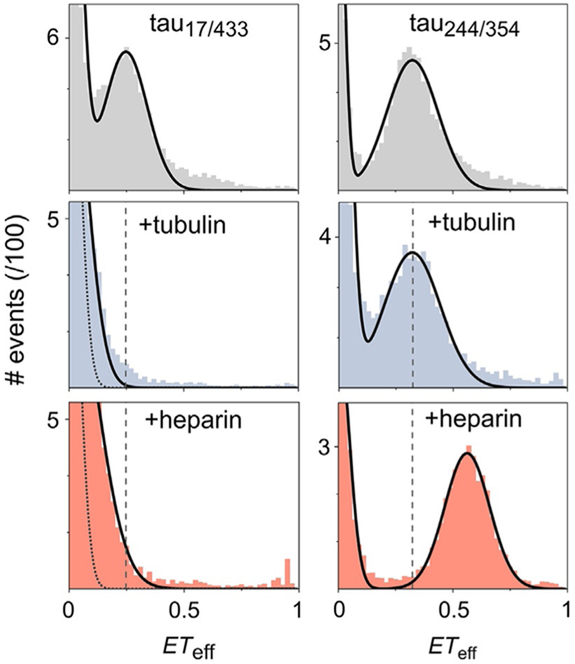

FIG. 4.

Contrasting conformational changes by heparin and tubulin by smFRET. smFRET histograms of tau in buffer (gray) or in the presence of 10μM tubulin (blue) or 10μM heparin (red). Tau 2N4R is labeled at residues 17 and 433 (tau17/433)or 244 and 354 (tau244/354), as indicated in the first row of histograms. The dashed lines are drawn from the mean ETeff of the measurements in buffer, to facilitate comparison of peak shifts. The measurements of tau17/433 reveal that upon binding to either heparin or tubulin, tau loses the long-range contacts between the MTBR and termini that are observed in solution, causing the histogram peaks to shift to ETeff~0. The dotted lines in these histograms denote the contribution of donor-only labeled protein to ETeff=0. In contrast, the microtubule binding region, as probed with tau244/354, adopts a more compact structure in the presence of heparin (seen in the shift of the histogram to higher ETeff), while no significant changes in the overall domain dimensions is observed in the presence of tubulin.

Adapted from Melo, A. M., Coraor, J., Alpha-Cobb, G., Elbaum-Garfinkle, S., Nath, A., & Rhoades, E. (2016). A functional role for intrinsic disorder in the tau–tubulin complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 14336–14341.

2.3. LABELING TAU FOR FCS MEASUREMENTS

Labeling of tau with a single fluorophore largely follows the protocol described earlier with minor modifications. Follow steps 1–3. At step 4, the fluorophore (Alexa Fluor 488) is added to a final 5:1 dye:protein molar ratio and the light-protected sample is incubated with stirring overnight at 4°C. Skip step 5 and follow steps 6–9.

2.4. TUBULIN PURIFICATION

Tubulin is purified from porcine/bovine brains according to the method of Castoldi and Popov (2003), aliquoted in BRB80 buffer (80mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 1mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) and stored at −80°C.

2.5. PREPARATION OF TUBULIN FOR smFRET AND FCS MEASUREMENTS

Thaw a tubulin aliquot rapidly at 37°C and store on ice immediately.

Clarify cold tubulin by centrifugation at 100,000×g for 6 min at 4°C and collect supernatant on ice.

Exchange into measurement buffer (20mM Tris, pH 7.4, and 50mM NaCl) using a Micro Bio-Spin column (6000MW limit, Biorad) at 4°C.

Determine tubulin concentration by absorbance at 280nm using an extinction coefficient of 115,000M−1cm−1

Store the protein on ice for no more than 2h.

Note

In order to maintain tubulin in a soluble state (nonpolymerized or aggregated), all steps should be carried out at 4°C and use precooled buffers, centrifuge, and rotors.

2.6. PREPARATION OF HEPARIN

We typically make 3mM heparin stock solutions. Low molecular-weight heparin (3000 g/mol, from MP Biomedicals) is dissolved in ultrapure water and stored at 4°C in 100 μL aliquots. Just prior to a measurement, the stock solution is diluted into measurement buffer.

2.7. PREPARATION OF PEG-PLL STOCK SOLUTION

Poly-l-lysine (PLL) conjugated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) is used to passivate sample chambers used for both FCS and smFRET measurements. Having tried several other options, our experience is that PEG-PLL is the most effective at minimizing nonspecific adsorption of protein to the chamber surfaces. Our protocol is adapted from a previously published one (Kenausis et al., 2000).

Add 2.5mL of 50mM borate buffer, pH 8.5, to 100mg of PLL hydrobromide (Sigma P-7890) to make a 40mg/mL PLL solution.

Vortex PLL solution for 30min.

Assemble a 3mL syringe and 0.22μm syringe filter. Rinse the filter membrane with borate buffer and filter the PLL solution.

Weigh 250mg of 2kDa mPEG-SPA (NANOCS) and transfer to a 5mL Eppendorf tube. Add the filtered PLL solution to make a 100mg/mL PEG solution.

Vortex the solution to dissolve PEG. Protect the reaction from light and incubate for 6h at RT.

Transfer the sample to 7kDa MW dialysis tubing (for example, Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes, Thermo-Fisher) and dialyze overnight at RT against 2L ultrapure water. We typically observe a 4–5× increase in total volume during dialysis, so care must be taken not to overload dialysis tubing or cassettes.

Following overnight dialysis, dialyze another 2–4h in fresh water.

Aliquot and store at −20°C. 125 μL is sufficient to coat 2 eight-well Nunc chambers and is a convenient volume.

Notes

- The reaction buffer is always freshly prepared. To make 10mL of 50mM borate buffer, pH 8.5:

- Weigh 123.7mg of boric acid (H3BO3) and dissolve in 10mL ultrapure water to make a 0.2M solution.

- Weight 191mg of sodium tetraborate decahydrate (Na2B4O7•10H2O) and add 1–2mL of ultrapure water. Add ~3mL of the boric acid solution to dissolve completely. Vortex thoroughly and continue to add boric acid until the solution reaches pH 8.5. Adjust final volume to 10mL with ultrapure water.

2.8. PREPARATION OF SAMPLE CHAMBERS

We use Nunc eight-well chambered coverslips (#1.0 borosilicate) for both smFRET and FCS measurements. Nonspecific adsorption of proteins to glass surfaces make these measurements challenging: (i) they impact reproducibility as the amount adsorbed may change from chamber to chamber, such that achieving the target concentration of single-molecule measurements is difficult and (ii) quantitative measurements for binding require accurate concentrations.

Prepare PEG-PLL for use by diluting stock solution 40× in ultrapure water.

Activate the glass surface by placing coverslips in a plasma cleaner (Harrick Plasma) for 1 min. This makes the glass surface hydrophilic.

Immediately add 300μL of diluted PEG-PLL to each chamber and incubate overnight at RT.

Following incubation, rinse chambers thoroughly 10× with ultrapure water.

Fill chambers with ultrapure water and incubate for at least 3h. Exchange water to sample buffer just prior to each measurement.

Note

Coverslips are typically used within 4–5 days. They can be stored filled with water in a wet box to minimize evaporation. We use an empty pipette tip box, with water in the bottom compartment and the coverslips on the perforated separator so that the environment is humid, but the coverslips are not submerged.

3. INSTRUMENTATION

While there are some commercial options for smFRET (for example, the MicroTime 200 from PicoQuant) and FCS measurements (PicoQuant, Zeiss, and Leica), many instruments are lab built. Typically, they are based on an inverted confocal microscope containing a high numerical aperture (NA) objective and avalanche photodiode detectors (APDs) (see Fig. 1 for general instrument setup). Instruments in our lab use an Olympus IX-71 microscope with a 60×/1.2NA water immersion objective (Olympus). A 488-nm continuous-wave laser (Spectra-Physics or Coherent) is steered into the back aperture of the objective, which focuses it to a diffraction-limited volume within the sample. Fluorescence emission is collected through the same objective, separated from excitation light using an appropriate dichroic mirror and emission filter (Chroma) and then focused into a small diameter aperture to achieve confocal discrimination. The combination of a small excitation volume and the confocal pinhole creates an observation volume of ~ 1fL. Finally, the emitted light is directed onto the detection area of a high quantum yield and low background detector. Our instruments use 50 or 100μm diameter optical fibers (OzOptics) to achieve the confocal aperture and also allow for direct coupling to APDs (SPCM-AQRH-14; Excelitas). Output from the detectors is registered using a digital correlator (Flex03LQ-12; correlator.com).

For both techniques, specific settings/components used for measurements with Alexa Fluor 488 as the FCS/smFRET donor fluorophore and Alexa Fluor 594 as the smFRET acceptor are described below:

FCS: The laser power is adjusted to ~5μW as measured just prior to entering the microscope. A Z488rdc long-pass dichroic in combination with a HQ600/200m band-pass filter is used for excitation/emission. The collected emission is focused onto the aperture of a 50μm diameter optical fiber.

smFRET: The laser power is adjusted to ~30–35μW as measured just prior to entering the microscope. The fluorescence emission is collected using a Z488rdc dichroic in combination with a 500nm long-pass filter. The donor and acceptor photons are separated using an HQ585lp dichroic in combination with ET525/50m and HQ600lp filters for donor and acceptor, respectively. The dichroics and filters are chosen to maximize collection of fluorescence emission and while minimizing cross-talk between the detection channels. Two 100μm diameter aperture fibers are used to couple the fluorescence emission to the detectors.

4. MEASUREMENTS OF TAU BINDING TO TUBULIN OR OTHER PARTNERS

4.1. FCS DATA COLLECTION

Align the microscope and verify alignment by measuring a reference standard. We use ~20nM solution of Alexa Fluor 488 hydrazide in water. Ten autocorrelation curves of 10s each are collected and analyzed as described later. For a given laser power, the diffusion time, number of molecules, and counts per molecule (cpm) should be consistent from day to day. Deviations beyond the standard error in these parameters or systematic biased residuals observed in the analysis of the dye (Eq. 2) indicate problems with the alignment or other instrument issues.

Acquire one 30s trace of a blank sample. This will contain all components of the sample except the fluorescently labeled tau. To illustrate, if tau alone is being measured, the blank will contain only buffer. If binding to 10μM tubulin is being measured, then the blank contains buffer and 10μM tubulin. This measurement should result in a flat autocorrelation curve (no autocorrelation) and serves as a check for contamination. It may also be used for background subtraction for accurate determination of number of molecules in low intensity samples.

Single-labeled tau is added to the blank sample to a final concentration ranging from ~2 to 200nM, mixed by pipetting 3–6 times, and allowed to equilibrate for 5–10min. Tau adsorbs to the pipette tips, and consistency in the number of pipette mixing between samples will increase reproducibility.

Between 10 and 30 autocorrelation curves of 10s duration are collected for each sample.

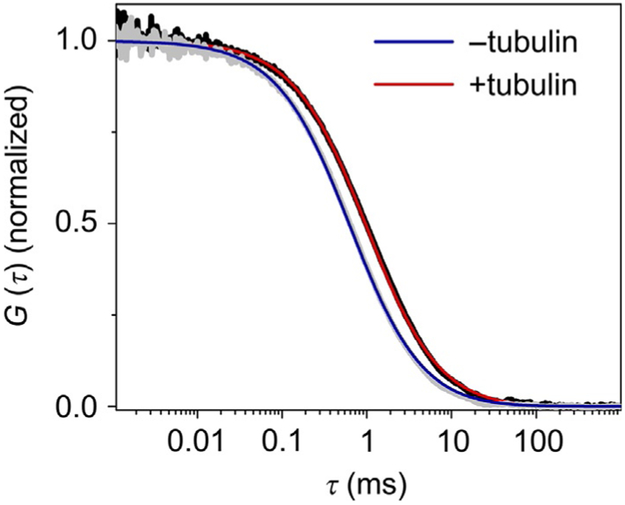

Binding experiments utilize a constant concentration of fluorescently labeled tau, with varying concentrations of the unlabeled binding partner. As seen in Fig. 2, the autocorrelation curves of fluorescently labeled tau shift to the right upon binding to tubulin, reflecting the larger size of the diffusing complex.

FIG. 2.

FCS measurement of tau binding tubulin. Normalized autocorrelation curves of the longest isoform of tau (2N4R, labeled at residue 433) in the absence (gray) or presence of 10μM unlabeled tubulin (black). Upon binding to tubulin, the autocorrelation curve shifts to right, reflecting the diffusion of large species (tau–tubulin complex). The blue and red lines are the fits of the autocorrelation curves in the absence and presence of tubulin, respectively, with Eq. (2) (one-component model), as described in Section 4.1.1

Note

When possible, it is helpful to independently characterize each of the components in the binding experiment by FCS. To illustrate, the first point in a binding curve is always fluorescently labeled tau in the absence of binding partner. Measurement of fluorescently labeled tubulin will yield the diffusion time of the soluble dimer which may be useful interpreting the size of tau–tubulin complexes.

4.1.1. FCS data analysis

The output of a FCS measurement is the time-correlated fluorescence signal shown as an autocorrelation curve. This technique quantifies the self-similarity of fluorescence fluctuations at a given time t, δF(t), and after a delay time τ, δF(t+τ), by calculating the normalized autocorrelation function, G(τ):

| (1) |

where F(t) is the fluorescence intensity as a function of time t and δF(t)=F(t)–⟨F(t)⟩. The angular brackets refer to time averaging and τ is the correlation time. To obtain the physical parameters of interest, the experimental autocorrelation curves are fitted by an appropriate mathematical model.

For a single diffusing species undergoing Brownian motion in a threedimensional Gaussian volume (an approximation for the confocally defined observation volume), the autocorrelation function is described by:

| (2) |

where N is the average number of fluorescent molecules in the observation focal volume, s is the structure factor defined as the ratio of radial to axial dimensions of the focal volume, and τD is the translational diffusion time of the molecule, which corresponds to the average time that a molecule resides in the observation volume.

4.1.1.1. Fitting FCS curves

The parameter s is determined by globally fitting the autocorrelation curves obtained for a range of Alexa 488 hydrazide concentrations with a 1-component fit function (Eq. 2). Both s and τD are linked in the analysis with the goal of robust determination of s. Generally, optical alignment with single photon excitation is considered good when s is within the range of 0.16–0.25 and flat residuals to the fit are obtained. Once determined, s is fixed for fitting of autocorrelation measurements of protein.

Characterization of tau in solution: Fit the average autocorrelation curve obtained for tau in buffer with Eq. (2), with s fixed to the value determined as described earlier (Step 1).

Characterization of tau and binding partners: Initial fitting should follow that of tau in solution (earlier). However, if fits are poor and the residuals are not random, more complex models may be required (Rigler & Elson, 2001).

4.2. smFRET DATA COLLECTION

Align the microscope and verify alignment by measuring and analyzing the diffusion of a standard fluorophore and the ETeff of a smFRET reference standard (see Notes).

Add blank sample to a fresh sample chamber (see Section 4.1) and make a 1 min measurement.

Add ~50 pM donor–acceptor-labeled tau to the sample chamber, mix by pipetting solution 3–6 times, and allow to equilibrate for 5–10min.

Make a 1min measurement of the tau sample. Along with the 1min blank sample measurement, this will be used to determine a threshold for further analysis and to assess the protein concentration (see details in the next section).

Make a longer (generally 30–60min) measurement of the sample. Binding experiments utilize a constant concentration of fluorescently labeled tau, with varying concentrations of the unlabeled binding partner. As seen in Fig. 3, in the absence of binding partner, only the ETeff=0 peak and free protein peak are observed. With increasing concentrations of either heparin or tubulin, a bound protein peak appears and increases, concomitant with the loss of prominence of the free protein peak.

Notes

Alignment of the smFRET instrument is first checked by measuring the diffusion of the Alexa 488 hydrazide sample as described earlier in the FCS session. In addition to checking for consistency in τD, cpm, and N, this sample is used to determine the fraction of donor fluorescence that is detected in the acceptor channel (β in Eq. 3).

Collect a 10–20 min data set of a well-characterized positive control. We use a 10-mer of dsDNA labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 on one strand (A488-CGGATCTCGG) and Alexa Fluorophore 594 on the other strand (A594-CCGAGATCCG). Deviations beyond expected noise of the mean ETeff and width of the histograms of this sample indicate an issue with the alignment or instrument.

Diffusion-based smFRET measurements are particularly sensitive to background fluorescence. Whenever possible spectroscopic grade components should be used to make buffers.

For smFRET measurements of tau, as well as other large intrinsically disordered proteins, where cooperative conformational changes may be lacking or domain dependent (Elbaum-Garfinkle & Rhoades, 2012; Melo et al., 2016), it may be of interest to probe different domains. The data shown in Fig. 4 provide an example of this for tau binding to both tubulin and heparin.

4.2.1. smFRET data analysis

4.2.1.1. Thresholding

The data stream from the detectors to our software is the number of photons in each detector (i.e., donor and acceptor) per 1-ms time bin. From these data, bursts arising from fluorescently labeled protein must be discriminated from background. To do so, we apply a threshold approach. This is determined by first summing the photons in both detectors for the 1-min blank and sample measurements. From this, we calculate the number of FRET events as function of varying the number of photons which define a protein event. This number, the threshold, is chosen based both on minimizing the number of events measured in a blank sample as well as maximizing the ratio of sample to blank events (Trexler & Rhoades, 2010). We have found that for our instrument and measurement conditions, a threshold of ~30 photons is common.

4.2.1.2. Calculating ETeff

After thresholding, ETeff values are calculated for each remaining photon burst as:

| (3) |

where Ia and Id are the fluorescence intensities collected in the acceptor and donor channels, respectively; β accounts for donor fluorescence bleed through into the acceptor channel; γ corrects for the difference in donor (ηd) and acceptor (ηd) detection efficiency, and quantum yield for donor (Φd) and acceptor (Φa) fluorophores (Ferreon, Gambin, Lemke, & Deniz, 2009):

| (4) |

4.2.1.3. Plotting data and analysis

The output of our analysis is the ETeff values calculated for each selected burst, which are plotted as a histogram. Each smFRET histogram contains a peak with a mean ETeff=0 which is due to molecules with photobleached, absent, or nonfluorescent acceptor dyes (Figs. 3 and 4). The histograms are fitted with a multipeak Gaussian function, to account for this peak as well as events for donor–acceptor-labeled protein. We use lab-written Matlab scripts for analysis.

In addition to calculating the ETeff values, we track burst “size” (number of 1ms bins associated with each burst), burst brightness (sum of donor and acceptor channels), and the number of events as a function of time. The first two parameters may help exclude events associated with large, nonspecific aggregates, or determine whether a sample is aggregating over the course of the measurement. The last parameter allows for monitoring of the sample concentration over time.

4.2.1.4. Calculating distances

Since tau is intrinsically disordered in solution and remains largely unstructured even upon binding to tubulin or heparin (Elbaum-Garfinkle & Rhoades, 2012; Melo et al., 2016), it displays a high conformational heterogeneity which results in a broad distribution of donor-acceptor distances. Therefore, in contrast to folded proteins, there is not a single fixed intramolecular distance, and thus the eponymous Förster equation does not provide an accurate conversion between calculated ETeff and distances. Rather, a number of polymer models have been used to account for the structural and dynamic heterogeneity and provide more accurate calculations of distance (O’Brien, Morrison, Brooks, & Thirumalai, 2009). These models allow for conversion of mean ETeff values into root mean squared (RMS) end-to-end distances by taking into account the end-to-end probability function P(r) into the Förster equation (Eq. 6) as follows:

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

where r is the distance between donor and acceptor fluorophores, R0 is the Förster radius of donor–acceptor pair, and ⟨r2⟩½ is the RMS distance. In our work, we have used the Gaussian coil model, but other polymer models, such as the worm-like and excluded-volume chains have also been applied to disordered proteins (Schuler et al., 2016).

5. SUMMARY

Tau is a highly dynamic, conformationally flexible microtubule-associated protein with important roles in regulating the dynamic instability of microtubules in the axons of neurons. In tau-mediated neurodegeneration, both loss of this native function as well as aggregation of tau are thought to be important. In this chapter, we overview the application of FCS and smFRET to the study of tau conformational ensembles and interactions. We demonstrate their use in quantifying the conformational changes and molecular interactions relevant both to tau function and aggregation. The experimental approaches described here can be extended to other disordered proteins and this chapter provides a general framework for investigating interactions between these proteins and molecular binding partners. This may be of particular use for the study of other aggregating or microtubule-associated proteins, where molecular features relevant to the critical initial stages of these processes are often masked by the ensemble nature of protein polymerization or self-association.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge support of NIH grant RF1AG053951 (to E.R.) and postdoctoral funding to A.M.M. through the NSF Science and Technology Center for Engineering Mechanobiology, CMMI-1548571.

REFERENCES

- Bacia K, Kim SA, & Schwille P (2006). Fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy in living cells. Nature Methods, 3, 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee PR, & Deniz AA (2014). Shedding light on protein folding landscapes by single-molecule fluorescence. Chemical Society Reviews, 43, 1172–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunden KR, Trojanowski JQ, & Lee VM (2009). Advances in tau-focused drug discovery for Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 8, 783–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoldi M, & Popov AV (2003). Purification of brain tubulin through two cycles of polymerization-depolymerization in a high-molarity buffer. Protein Expression and Purification, 32, 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, & Rhoades E (2008). Fluorescence characterization of denatured proteins. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 18, 516–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirita CN, Congdon EE, Yin H, & Kuret J (2005). Triggers of full-length tau aggregation: A role for partially folded intermediates. Biochemistry, 44, 5862–5872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland DW, Hwo SY, & Kirschner MW (1977). Physical and chemical properties of purified tau factor and the role of tau in microtubule assembly. Journal of Molecular Biology, 116, 227–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel DN, Hyman AA, Cobb MH, & Kirschner MW (1992). Modulation of the dynamic instability of tubulin assembly by the microtubule-associated protein tau. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 3, 1141–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Cobb G, Compton JT, Li XH, & Rhoades E (2014). Tau mutants bind tubulin heterodimers with enhanced affinity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, 6311–6316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Ramlall T, & Rhoades E (2010). The role of the lipid bilayer in tau aggregation. Biophysical Journal, 98, 2722–2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum-Garfinkle S, & Rhoades E (2012). Identification of an aggregation-prone structure of tau. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 134, 16607–16613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreon AC, Gambin Y, Lemke EA, & Deniz AA (2009). Interplay of alpha-synuclein binding and conformational switching probed by single-molecule fluorescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 5645–5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster T (1948). Zwischenmolekulare Energiewanderung und Fluoreszenz. Annalen der Physik, 437, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Friedhoff P, Schneider A, Mandelkow EM, & Mandelkow E (1998). Rapid assembly of Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments from microtubule-associated protein tau monitored by fluorescence in solution. Biochemistry, 37, 10223–10230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haustein E, & Schwille P (2003). Ultrasensitive investigations of biological systems by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Methods, 29, 153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess ST, Huang S, Heikal AA, & Webb WW (2002). Biological and chemical applications of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: A review. Biochemistry, 41, 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohlbein J, & Kapanidis AN (2016). Probing the conformational landscape of DNA polymerases using diffusion-based single-molecule FRET. Methods in Enzymology, 581, 353–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenausis GL, Voros J, Elbert DL, Huang NP, Hofer R, Ruiz-Taylor L, et al. (2000). Poly(L-lysine)-g-poly(ethylene glycol) layers on metal oxide surfaces: Attachment mechanism and effects of polymer architecture on resistance to protein adsorption. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 104, 3298–3309. [Google Scholar]

- Konig I, Zarrine-Afsar A, Aznauryan M, Soranno A, Wunderlich B, Dingfelder F, et al. (2015). Single-molecule spectroscopy of protein conformational dynamics in live eukaryotic cells. Nature Methods, 12, 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XH, Culver JA, & Rhoades E (2015). Tau binds to multiple tubulin dimers with helical structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 137, 9218–9221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machan R, & Wohland T (2014). Recent applications of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy in live systems. FEBS Letters, 588, 3571–3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo AM, Coraor J, Alpha-Cobb G, Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Nath A, & Rhoades E (2016). A functional role for intrinsic disorder in the tau-tubulin complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 14336–14341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalet X, Weiss S, & Jager M (2006). Single-molecule fluorescence studies of protein folding and conformational dynamics. Chemical Reviews, 106, 1785–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Maeda S, Vossel K, & Mucke L (2011). The many faces of tau. Neuron, 70, 410–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MC, Rasnik I, Cheng W, Lohman TM, & Ha T (2004). Probing single-stranded DNA conformational flexibility using fluorescence spectroscopy. Biophysical Journal, 86, 2530–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien EP, Morrison G, Brooks BR, & Thirumalai D (2009). How accurate are polymer models in the analysis of Forster resonance energy transfer experiments on proteins? Journal of Chemical Physics: 130 124903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigler R, & Elson ES (2001). Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: Theory and applications. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Roy R, Hohng S, & Ha T (2008). A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nature Methods, 5, 507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler B, Muller-Spath S, Soranno A, & Nettels D (2012). Application of confocal single-molecule FRET to intrinsically disordered proteins. Methods in Molecular Biology, 896, 21–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler B, Soranno A, Hofmann H, & Nettels D (2016). Single-molecule FRET spectroscopy and the polymer physics of unfolded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Annual Review of Biophysics, 45, 207–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweers O, Schonbrunn-Hanebeck E, Marx A, & Mandelkow E (1994). Structural studies of tau protein and Alzheimer paired helical filaments show no evidence for beta-structure. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 269, 24290–24297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trexler AJ, & Rhoades E (2010). Single molecule characterization of alpha-synuclein in aggregation-prone states. Biophysical Journal, 99, 3048–3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinczek B, Biernat J, Baumann K, Mandelkow EM, & Mandelkow E (1995). Domains of tau protein, differential phosphorylation, and dynamic instability of microtubules. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 6, 1887–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi S, & Lemke EA (2013). Genetically encoded click chemistry for single-molecule FRET of proteins. Methods in Cell Biology, 113, 169–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, & Mandelkow E (2016). Tau in physiology and pathology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17, 5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten MD, Lockwood AH, Hwo SY, & Kirschner MW (1975). A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 72, 1858–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]