Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed (1) to perform a systematic review on scanning parameters and contrast medium (CM) reduction methods used in prospectively electrocardiography (ECG-triggered low tube voltage coronary CT angiography (CCTA), (2) to compare the achievable dose reduction and image quality and (3) to propose appropriate scanning techniques and CM administration methods.

Methods:

A systematic search was performed in PubMed, the Cochrane library, CINAHL, Web of Science, ScienceDirect and Scopus, where 20 studies were selected for analysis of scanning parameters and CM reduction methods.

Results:

The mean effective dose (HE) ranged from 0.31 to 2.75 mSv at 80 kVp, 0.69 to 6.29 mSv at 100 kVp and 1.53 to 10.7 mSv at 120 kVp. Radiation dose reductions of 38 to 83% at 80 kVp and 3 to 80% at 100 kVp could be achieved with preserved image quality. Similar vessel contrast enhancement to 120 kVp could be obtained by applying iodine delivery rate (IDR) of 1.35 to 1.45 g s−1 with total iodine dose (TID) of between 10.9 and 16.2 g at 80 kVp and IDR of 1.08 to 1.70 g s−1 with TID of between 18.9 and 20.9 g at 100 kVp.

Conclusion:

This systematic review found that radiation doses could be reduced to a rate of 38 to 83% at 80 kVp, and 3 to 80% at 100 kVp without compromising the image quality.

Advances in knowledge:

The suggested appropriate scanning parameters and CM reduction methods can be used to help users in achieving diagnostic image quality with reduced radiation dose.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary CT angiography (CCTA) has emerged as a non-invasive modality of choice for the detection of coronary artery disease, particularly for the investigation of symptomatic patients with low-to-intermediate cardiovascular risk (approximately 20 to 70%).1, 2 However, radiation exposure and the administration of contrast medium (CM) are reasons of concern in patients undergoing CCTA. Several techniques have been developed to reduce radiation exposure. These include low tube voltage protocol,3 electrocardiography (ECG)-dependent tube current modulation,4 prospectively ECG-triggered protocol,5, 6 high-pitch helical scanning with dual-source CT,7 application of noise reduction filters8 and optimisation of scan length.9

Prospectively ECG-triggered protocol has been recommended as the first line default technique for CCTA examination, which should be used whenever possible and practical.10 The scanning is mostly performed using standard peak voltage of 120 kVp and iodinated CM. The iodine delivery rate (IDR) ranges from 0.99 to 2.22 g s−1 and total iodine dose (TID) is between 11.1 to 56.0 g.11

In the last decade, various studies have tried to reduce radiation exposure in CCTA by lowering the tube voltage to 80 and 100 kVp, together with reduced iodine doses.12–19 The low tube voltages will generate less X-ray photons in the CT tube when the same tube current is applied. This can be explained with technical reasons, such as lower tube effectiveness at low tube voltage and the heavy filtering of low-kV photons.20, 21 At the same time, as the mean photon energy of low tube voltage approaches the iodine K-edge energy of 33 keV, it produces better image contrast, meaning an equivalent vessel contrast enhancement can be achieved at a lower amount of administered iodine.22, 23

Despite its advantages, increased image noise remains a drawback in the low tube voltage protocol. Since tube output is proportional to the square of tube voltage, a reduction from 120 to 100 kVp will result in 31% less X-ray photons being produced, and this figure will increase to 56% with further reduction to 80 kVp. Image noise is proportional to the square root of X-ray photons, thus more noise will be generated when using lower tube voltage at the same tube current. One solution to improve image quality is to increase the tube current to balance image noise. However, this may end up increasing the radiation dose, especially for larger-sized patients.20

To address this issue, CT scanner manufacturers have introduced different protocols based on lower tube voltage and/or tube current combined with iterative reconstruction (IR) and other radiation dose-reducing techniques, together with CM reduction method.24 The scanning parameters are dependent on hardware (CT scanner) specifications. There is no consensus on the extent of radiation dose reduction and how the image quality can be preserved when different scanning techniques and CM reduction methods are applied.

Therefore, this study aims to systematically review the current prospectively ECG-triggered low tube voltage CCTA protocols to provide an overview of various scanning techniques and CM reduction methods, to assess reported achievable radiation dose reduction and image quality. We also summarise and propose appropriate scanning techniques and CM administration methods for achieving diagnostic image quality with low dose exposure.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Data sources and study selection

This review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.25 A systematic search of PubMed, the Cochrane library, CINAHL, Web of Science, ScienceDirect and Scopus was performed without publication date limitation. The following Medical Subject Heading terms and the free keywords were used to identify studies on low tube voltage CCTA protocol: (“heart” OR “cardiac” OR “coronary”) AND (“tomography, X-ray computed” OR “computed tomography angiography”) OR (“tomography” AND “X-ray” AND “computed”) OR “X-ray computed tomography” OR [(“computed” AND “tomography”) OR (“computed tomography”)] AND [(low AND voltage) OR (tube AND voltage)] (last search, 30 September, 2017). Furthermore, the reference lists of retrieved articles were manually scrutinized to identify potential relevant studies.

The inclusion criteria included: (1) study that compared radiation dose and/or image quality between 120 kVp and low tube voltage protocols; (2) scanning was performed using a multidetector CT scanner with minimum 64 detector-row; (3) prospectively ECG-triggered CCTA protocol was used; (4) quantitative measurement of vessel contrast enhancement and/or the following parameters: image noise, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR); qualitative image quality; and air-kerma length product (PKL) and (5) published in peer reviewed journals written in English language.

Studies that involved paediatric populations were excluded to avoid bias in radiation dose and image quality assessment due to use of different cardiac CT scanning protocols in paediatric patients when compared to adult cardiac patients. Furthermore, radiation dose measurement using ex vivo phantoms only were excluded. However, for studies that involved both phantoms and human participants, the data from human participants were included in this review. The methodological quality of included studies were assessed by using the QUADAS-2 checklist.26 Two authors screened all articles and extracted the data independently. Disagreement on inclusion of eligible studies was resolved by consensus between the two authors.

Data extraction

Publications considered eligible were scored using a standardised extraction form, which included the first author, publication date, title, journal, participant characteristics, CM injection parameters, type of CT system, image acquisition techniques and parameters, image reconstruction techniques, reported dose and image quality measurements.

The primary outcomes were effective dose (HE) (mSv), quantitative [vessel contrast enhancement (HU), image noise, SNR and CNR] and qualitative image quality. HE was calculated by multiplying the PKL with the conversion coefficient of 0.014 mSv∙mGy−1∙cm−1 for the chest region. For quantitative and qualitative image quality assessment, the differences were classified as “improved”, “similar” or “lower” compared with 120 kVp protocol. A statistically significant (p < 0.05) improvement of image quality was classified as “improved”, non-statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) was classified as “similar” and a statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease in image quality was classified as “lower”. The scanning parameters used in the selected studies were summarised and the optimum protocols were suggested.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (v. 23.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Correlations between HE and publication year were tested using Spearman’s rank correlation test. 95% confidence interval was used and a p-value below 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study selection

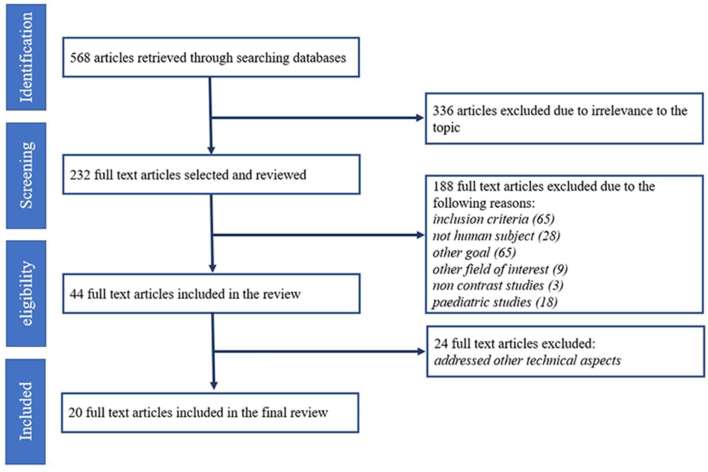

In the primary literature search, 1357 articles were identified, of which 789 were duplicates, leaving 568 potential articles for analysis. A total of 336 articles were excluded due to irrelevant topics. Of the remaining 232 full text articles, 188 articles were excluded during the screening process because they either (i) did not fulfil inclusion criteria (n = 65); (ii) did not involve human subjects (n = 28); (iii) focused on other goal (n = 65); (iv) focused on other field of interest (n = 9); (v) focused on paediatrics (n = 18); and (vi) involved non-contrast studies only (n = 3). Of the remaining 44 articles, 24 were excluded because the studies were addressing other technical aspects. Therefore, only 20 studies were finally selected for analysis.15–19,27–41 A detailed overview of the inclusion and data extraction processes is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The study selection flow.

Study characteristics

The study characteristics are provided in Tables 1 and 2. The studies were published in 2008 (n = 1), 2011 (n = 2), 2013 (n = 3), 2014 (n = 1), 2015 (n = 7) and 2016 (n = 6). Among all, 4 studies compared the radiation dose and image quality produced at 80 and 120 kVp, 11 studies involved the comparison between 100 and 120 kVp, while 5 studies involved the comparison between 80, 100 and 120 kVp.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of studies that compared between 80 and 120 kVp protocols

| Study characteristics | 80 kVp group | Techniques | Mean HE (mSv) | Decrease in HE(%) | Vessel contrast enhancement | Image quality | ||||||||

| Author/year of publication | Total no. of patient | No. of patient | BMI (kg m–2) | Patient selection | Image acquisition | Image reconstruc-tion | 80 kVp | 120 kVp | Noise | SNR | CNR | Qualitative image quality | ||

| Nakaura et al 201318 | 68 | 35 | NR | NIL | ATCM (Ref. image) |

iDose4a | 1.40 | 5.40 | 74 | = | = | NR | = | = |

| Zheng et al 201441 | 100 | 25 | 20.90 | BMI < 25 | ATCM (300 mAs ref.) |

SAFIREa | 0.41 | 2.37 | 83 | NR | = | NR | NR | = |

| Oda et al 201533 | 60 | 30 | 22.20 | NIL | ATCM (SD of noise) |

AIDR 3Db | 1.50 | 2.40 | 38 | ↑ | = | NR | ↑ | = |

| Zhang et al 201538 | 101 | 31 | 21.89 | BMI < 23 | ATCM (Noise index, 100–700 mA) |

ASIRa | 1.51 | 4.92 | 69 | ↑ | ↑ | = | = | = |

| Zhang et al 201540 | 90 | 30 | 22.10 | NIL | ATCM (400 mAs ref.) |

FBPa | 2.75 | 9.29 | 70 | ↑ | ↑ | = | = | = |

| Durmus et al 201628 | 302 | 56 | 22.80 | ATVS | ATCM (398 mAs ref.) |

FBPa | 0.31 | 1.53 | 80 | NR | ↑ | NR | = | = |

| Iyama et al 201617 | 60 | 30 | NR | NIL | ATCM (Ref. image) |

IMRa | 1.40 | 5.40 | 74 | ↑ | = | NR | ↑ | = |

| Mangold et al 201631 | 153 | 39 | 26.60 | ATVS | ATCM (mAs ref.) |

ADMIREb | 2.40 | 10.7 | 78 | ↑ | ↑ | = | = | = |

| Wu et al 201619 | 154 | 75 | 23.70 | NIL | ATCM (285 mAs ref.) |

SAFIREa | 0.88 | 2.39 | 63 | = | = | = | = | = |

ADMIRE, Advanced Modelled Iterative Reconstruction; AIDR 3D, Adaptive Iterative Dose Reduction 3D; ASIR, Adaptive Statistical Iterative Reconstruction; ATCM, automatic tube current modulation; ATVS, automated tube voltage selection; BMI, body mass index; CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio; HE, effective dose; IMR, Iterative Model Reconstruction; NIL, non-existent; NR, not reported; SAFIRE, Sinogram-Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio.

↓, lower with low tube voltage protocol; ↑, improved with low tube voltage protocol; =, similar with low tube voltage protocol.

filtered back projection (FBP) reconstruction at 120 kVp.

iterative reconstruction (IR) at 120 kVp.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the studies compared between 100 and 120 kVp protocols

| Study characteristics |

100 kVp group |

Techniques | Mean HE (mSv) |

Decrease in HE (%) |

Vessel contrast enhance- ment |

Image quality | ||||||||

|

Author /year of publica- tion |

Total no. of patient | No. of patient |

BMI (kg m−2) |

Patient selection | Image acquisition | Image reconstruction |

100 kVp |

120 kVp |

Noise | SNR | CNR | Qualitative image quality | ||

| Alkadhi et al 200827 | 68 | 40 | 22.80 | BMI ≤ 25 | ATCM (190 mAs ref.) | FBPa | 1.11 | 2.38 | 53 | NR | NR | NR | NR | = |

| Gagarina et al 201116 | 70 | 70 | 25.80 | NIL | BMI adapted-tube current | FBPa | 0.81 | 4.06 | 80 | = | = | = | = | = |

| Zhang et al 201139 | 107 | 40 | 22.26 | BMI < 25 | BMI adapted-tube current | FBPa | 1.75 | 3.79 | 54 | = | = | NR | = | = |

| Khan et al 201329 | 78 | 33 | 23.00 | BMI < 27 | BMI adapted-tube current | FBPa | 3.71 | 5.31 | 30 | = | = | = | = | = |

| Nakaura et al 201332 | 100 | 50 | NR | NIL | ATCM (Reference image) |

FBPa | 2.80 | 5.20 | 46 | ↑ | ↑ | NR | = | ↓ |

| Zheng et al 201441 | 100 | 25 | 25.44 | NIL | ATCM (300 mAs ref.) | SAFIREa | 1.14 | 2.37 | 52 | = | = | NR | NR | = |

| Lu et al 201530 | 185 | 53 | 23.10 | CC ≤ 90 cm | CC-adapted tube current | FBPa | 2.36 | 3.82 | 38 | ↑ | = | ↑ | ↑ | = |

| Shen et al 201535 | 100 | 50 | 24.40 | NIL | ATCM (350 mAs ref.) | SAFIREa | 3.62 | 5.55 | 35 | = | = | = | = | = |

| Sun et al 201536 | 179 | 92 | 28.00 | NIL | BMI adapted-tube current | AIDR 3Da | 1.59 | 2.90 | 45 | ↓ | ↑ | = | = | = |

| Yin et al 201537 | 231 | 115 | 24.90 | NIL | ATCM (mAs ref.) | SAFIREa | 2.30 | 3.50 | 34 | = | = | = | = | = |

| Zhang et al 201538 | 101 | 34 | 25.24 | 23 < BMI < 28 | ATCM (Noise index, 150–660 mA) |

ASIRa | 2.59 | 4.92 | 48 | ↑ | ↑ | = | = | = |

| Zhang et al 201540 | 90 | 30 | 21.10 | ATVS | ATCM (400 mAs ref.) | FBPa | 6.29 | 9.29 | 32 | ↑ | ↑ | = | = | = |

| Cesare et al 201615 | 200 | 100 | 26.65 | NIL | ATCM (33 HU SD of noise, 50–550 mA) |

AIDR 3Db | 2.80 | 2.89 | 3 | ↑ | = | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Durmus et al 201628 | 302 | 125 | 25.90 | ATVS | ATCM (228 mAs ref.) | FBPa | 0.69 | 1.53 | 55 | NR | ↑ | NR | = | = |

| Mangold et al 201631 | 153 | 40 | 29.90 | ATVS | ATCM (mAs ref.) | ADMIREb | 5.90 | 10.7 | 45 | ↑ | = | = | = | = |

| Pan et al 201634 | 48 | 24 | 33.80 | NIL | BMI adapted-tube current | AIDR 3Da | 1.61 | 3.64 | 56 | = | = | = | = | = |

ADMIRE, Advanced Modelled Iterative Reconstruction; AIDR 3D, Adaptive Iterative Dose Reduction 3D; ASIR, Adaptive Statistical Iterative Reconstruction; ATCM, automatic tube current modulation; ATVS, automated tube voltage selection; BMI, body mass index; CC, chest circumference; CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio; HE, effective dose; HU, Hounsfield unit; NIL, non-existent; NR, not reported; SAFIRE, Sinogram-Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction; SD, standard deviation; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio.

↓, lower with low tube voltage protocol; ↑, improved with low tube voltage protocol; =, similar with low tube voltage protocol.

filtered back projection (FBP) reconstruction at 120 kVp.

iterative reconstruction (IR) at 120 kVp.

In five studies, HE was recalculated from PKL because the reported HE was calculated with a different PKL-to-HE conversion coefficient (0.017 and 0.028 mSv∙mGy−1∙cm−1, respectively).16, 27,35,36,39 There was no correlation between publication year and HE for 80 kVp (p = 0.829, r = −0.085), 100 kVp (p = 0.392, r = 0.222) and 120 kVp (p = 0.447, r = −0.171).

Quantitative assessment of image quality was performed in 19 studies while qualitative assessment was performed in all the studies, mostly using 2- to 5-point Likert scale (3 studies were scored by 1 observer; 16 studies were scored by 2 observers; and 1 study was scored by 3 observers).

Radiation dose and image quality

The mean HE reported in the selected studies ranged from 0.31 to 2.75 mSv at 80 kVp, 0.69 to 6.29 mSv at 100 kVp and 1.53 to 10.7 mSv at 120 kVp. The radiation doses were reduced by 38 to 83% at 80 kVp and 3 to 80% at 100 kVp when compared with 120 kVp. The lowest doses at 80 kVp (0.31 mSv), 100 kVp (0.69 mSv) and 120 kVp (1.53 mSv) were reported by Durmus et al which combined automated tube voltage selection (ATVS) and automatic tube current modulation (ATCM) techniques.28 Nine studies reported increase in image noise at 80 kVp (n = 4) and 100 kVp (n = 5). Overall, improved or similar image quality was achieved in all the studies when using lower tube voltage, except in one study32 which reported deteriorating qualitative image quality at 100 kVp as compared to 120 kVp.

Scanning techniques used in prospectively ECG-triggered low tube voltage CCTA protocol

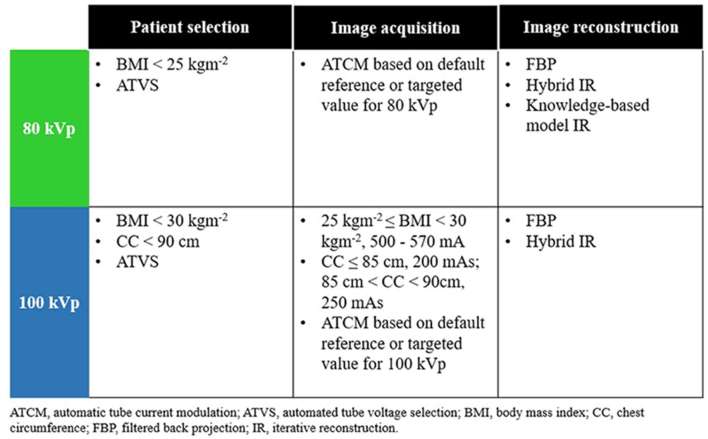

Different scanning techniques were used in the selected studies to achieve dose reduction and maintain image quality at low tube voltage settings (Table 3). The scanning techniques are categorized into three stages of CCTA examination: patient selection, image acquisition and image reconstruction.

Table 3.

Techniques used to achieve dose reduction and maintain image quality

| Stages of CCTA examination | Techniques | Definition | Application examples | |

| Patient selection | (1) BMI = weight (kg) / height2 (m2) | Selection of patient for low tube voltage protocol based on their BMI. | BMI ≤ 25 for 100 kVp. | Alkadhi et al 200827 |

| 30 ≥ BMI > 25 for 120 kVp. | ||||

| BMI < 25 for 100 kVp. | Zhang et al 201139 | |||

| BMI ≥ 25 for 120 kVp | ||||

| BMI < 27 for 120 kVp. | Khan et al 201329 | |||

| BMI ≥ 27 for 100 and 120 kVp. | ||||

| BMI < 25 for 80 kVp. | Zheng et al 201441 | |||

| BMI ≥ 25 for 100 and 120 kVp. | ||||

| BMI < 23 for 80 kVp. | Zhang et al 201538 | |||

| 23 < BMI < 28 for 100 kVp. | ||||

| BMI ≥ 28 for 120 kVp. | ||||

| (2) Measurement of nipple-level CC using a measuring tape. | Selection of patient for low tube voltage protocol based on their CC. | CC < 90 cm for 100 kVp. | Lu et al 201530 | |

| CC ≥ 90 cm for 120 kVp. | ||||

| (3) ATVS algorithm | Automatically select tube voltage based on patients’ size and attenuation characteristics estimated from topogram. | Care kV (Siemens Healthcare) | Zhang et al 201540 | |

| Durmus et al 201628 | ||||

| Mangold et al 201631 | ||||

| Image acquisition | (1) Manual tube current adaptation to: | |||

| (a) BMI | Manually set the tube current based on patients’ BMI. | At 100 kVp, 200 mA for BMI = 21; 570 mA for BMI = 30. | Gagarina et al 201116 | |

| At 120 kVp, 400 mA for BMI = 21; 500 mA for BMI = 30. | ||||

| At 100 kVp, 400–450 mA for BMI < 21; 450–500 mA for 22 ≤ BMI < 25. | Zhang et al 201139 | |||

| NR | Khan et al 201329 | |||

| Tube current was adjusted with a range of 330–480 mA | Sun et al 201536 | |||

| Tube current was adjusted with a range of 330–400 mA | Pan et al 201634 | |||

| (b) CC | Manually set the tube current based on patients’ CC. | At 100 kVp, 200 mAs for CC ≤ 85 cm; 250 mAs for 85 cm < CC < 90 cm. | Lu et al 201530 | |

| At 120 kVp, 200 mAs for 90 cm ≤ CC ≤ 95 cm; 250 mAs for CC > 95 cm. | ||||

| Image acquisition | (2) ATCM based on: | |||

| (a) Noise index | Automatically modulate the tube current to a target noise index to achieve constant image noise regardless of attenuation level. | Smart mA and Auto mA (GE Healthcare). | Zhang et al 201538 | |

| (b) Reference image | Automatically modulate the tube current based on reference image, regardless of attenuation level. It aims to keep the same image quality as in the reference image. | DoseRight (Philips Healthcare, Cleveland). | Nakaura et al 201318 | |

| Nakaura et al 201332 | ||||

| Iyama et al 201617 | ||||

| (c) Reference effective tube current-time product | Automatically modulate the tube current with reference to a target tube current level for a standard-sized patient to achieve constant image quality. | CareDose4D (Siemens Healthcare). | Alkadhi et al 200827 | |

| Zhang et al 201441 | ||||

| Shen et al 201535 | ||||

| Yin et al 201537 | ||||

| Zhang et al 201540 | ||||

| Durmus et al 201628 | ||||

| Mangold et al 201631 | ||||

| Wu et al 201619 | ||||

| (d) SD (noise) |

Automatically modulate the tube current to a target SD of noise to achieve constant image noise regardless of attenuation level. | SureExposure 3D (Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation). | Oda et al 201533 |

|

| Cesare et al 201615 | ||||

| Image reconstruction | (1) Statistical/Hybrid IR | A combination of FBP and IR, not fully iterative. | ADMIRE (Siemens Healthcare) | Mangold et al 201631 |

| AIDR 3D (Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation) | Oda et al 201533 | |||

| Sun et al 201536 | ||||

| Cesare et al 201615 | ||||

| Pan et al 201634 | ||||

| ASIR (GE Healthcare) | Zhang et al 201538 | |||

| iDose4 (Philips Healthcare) | Nakaura et al 201318 | |||

| SAFIRE (Siemens Healthcare) | Zheng et al 201441 | |||

| Shan et al 201535 | ||||

| Yin et al 201537 | ||||

| Wu et al 201619 | ||||

| (2) Knowledge-based model IR | Involving full IR algorithms with both forward and backward projection steps. | IMR (Philips Healthcare) | Iyama et al 201617 | |

ADMIRE, Advanced Modelled Iterative Reconstruction; AIDR 3D, Adaptive Iterative Dose Reduction 3D; ASIR, Adaptive Statistical Iterative Reconstruction; ATCM, automatic tube current modulation; ATVS, automated tube voltage selection; BMI, body mass index; CC, chest circumference; CCTA, coronary CT angiography; FBP, filtered back projection; IMR, Iterative Model Reconstruction; IR, iterative reconstruction; NR, not reported; SAFIRE, Sinogram-Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction; SD, standard deviation.

Manual and automatic processes were used to select patients. Manual selection was performed based on the patients’ body mass index (BMI) (n = 5) and chest circumference (CC) (n = 1). Automatic selection was used in three recent publications, involving a dedicated software (Care kV, Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany) to select the tube voltage based on the patients’ size and attenuation characteristics estimated from their topograms, or scout view (CT projection radiograph) acquired from an anteroposterior scan direction.

In image acquisition, manual adaptation and automatic modulation of tube current were applied. A few studies manually adapted the tube current to patients’ BMI (n = 5) and CC (n = 1). Whereas for the rest of the studies (n = 14), ATCM software developed by four CT scanner manufacturers (Smart mA and Auto mA, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI; DoseRight, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH; CareDose 4D, Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany; SureExposure 3D, Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Otawara, Japan) were used. The ATCM software tools were categorised into four groups based on their operation methods: noise index based, reference image based, reference effective tube current-time product based, and standard deviation (SD) based.

In terms of image reconstruction, majority of the studies applied IR techniques (12 out of 19 studies). Two types of IR algorithms were used; the statistical or hybrid IR and the knowledge-based iterative model IR. In general, statistical or hybrid IR involves a combination of filtered back projection (FBP) (analytical method) and IR algorithms (statistical method) in the image reconstruction process. Knowledge-based model IR is the latest technology using a full IR algorithm in the image reconstruction process.

Different statistical or hybrid IR algorithms were used namely the Advanced Modelled Iterative Reconstruction (ADMIRE, Siemens Healthcare, n = 1), Adaptive Iterative Dose Reduction (AIDR 3D, Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, n = 4), Adaptive Statistical Iterative Reconstruction (ASIR, GE Healthcare, n = 1), iDose4 (iDose4, Philips Healthcare, n = 1) and Sinogram-Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction (SAFIRE, Siemens Healthcare, n = 4). Only one study applied knowledge-based model IR [Iterative Model Reconstruction (IMR), Philips Healthcare] at 80 kVp.

The HE values from IR were compared to FBP at 80, 100 and 120 kVp. At 80 kVp, the median HE was 1.40 mSv (0.41 to 2.40 mSv) for IR and 1.53 mSv (0.31 to 2.75 mSv) for FBP. At 100 kVp, the median HE was 2.45 mSv (1.14 to 5.90 mSv) for IR and 2.06 mSv (0.69 to 6.29 mSv) for FBP. At 120 kVp, the median HE was 2.89 mSv (2.40 to 10.7 mSv) for IR and 3.82 mSv (1.53 to 9.29 mSv) for FBP.

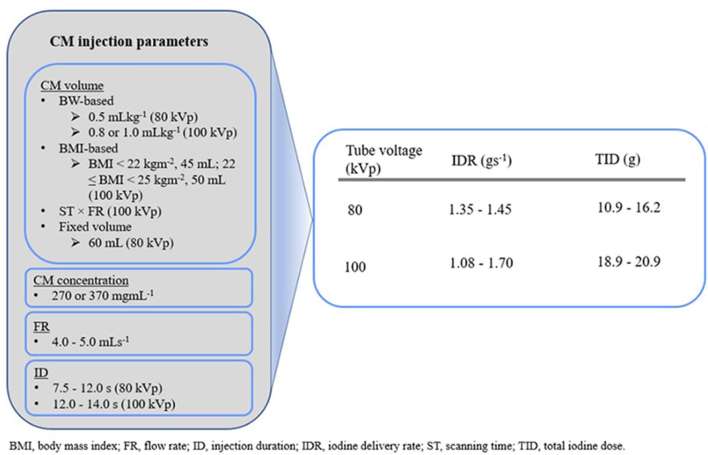

CM reduction and vessel contrast enhancement

Improved or similar vessel contrast enhancement was observed in all studies when low tube voltage was used, except in one study that reported lower vessel contrast enhancement at 100 kVp compared to 120 kVp (Tables 1 and 2). Table 4 shows the CM injection parameters used in the studies.

Table 4.

CM injection parameters

| Author/year of publication | Tube voltage (kVp) | Injection pattern | Method for CM volume calculation | CM concentration (mg ml−1) | FR (mls−1) | ID (s) | IDR (gs−1) | TID (g) | CM reduction compared to 120 kVp | Saline flush (ml) | Vessel contrast enhancement | |

| First bolus | Second bolus | |||||||||||

| Alkadhi et al 200827 | 100 | Biphasic | 0.8 ml kg–1 | CM volume same as first bolus; CM : saline = 1 : 5 | 320 | 4.4 | CM volume/FR | NR | NR | Yes | NIL | NR |

| Gagarina et al 201116 | 100 | Biphasic | 50 ml or 60 ml for body weight > 90 kg | NIL | 320 or 350 | 5.0 | 10.0–12.0 | 1.60–1.75 | 16.0–21.0 | No | 20 | = |

| Zhang et al 201139 | 100 | Triphasic | BMI < 22, 45 ml; 22 ≤ BMI < 25, 50 ml | 20 ml; CM : saline = 3 : 7 | 370 | 4.0–4.5 | 14.0 | 1.48–1.66 → 0.44–0.50 | 18.9–20.7 | Yes | 30 | = |

| Khan et al 201329 | 100 | Biphasic | 70 ml | NIL | 350 | 5.0 | 14.0 | 1.75 | 24.5 | No | 40 | = |

| Nakaura et al 201318 | 80 | Uniphasic | 0.5 ml kg−1 | NIL | 370 | CM volume/ID | 7.5 | 1.45 | 10.9 | Yes | NIL | = |

| Nakaura et al 201332 | 100 | Uniphasic | 1.0 ml kg−1 | NIL | 370 | CM volume/ID | 15.0 | 1.51 | 22.6 | No | NIL | ↑ |

| Zheng et al 201441 | 80 | Biphasic | 1.0 ml kg−1 | NIL | 270 | 5.0 | CM volume/FR | 1.35 | 15.5 | Yes | 40 | NR |

| 100 | Biphasic | 1.0 ml kg−1 | NIL | 270 | 5.0 | CM volume/FR | 1.35 | 19.6 | Yes | 40 | = | |

| Lu et al 201530 | 100 | Biphasic | 80 ml | NIL | 370 | 5.0 | 16.0 | 1.85 | 29.6 | No | 30 | ↑ |

| Oda et al 201533 | 80 | Biphasic | 0.6 ml kg−1 | NIL | 370 | CM volume/ID | 10.0 | 1.12 | 11.2 | Yes | 40 ml, 4 ml s−1 |

↑ |

| Shen et al 201535 | 100 | Biphasic | 1.0 ml kg−1 | NIL | 270 | 5.0 | CM volume/FR | 1.08 | 20.4 | Yes | 40 | = |

| Sun et al 201536 | 100 | Biphasic | 0.9 ml kg−1 | NIL | 270 | 5.0 | CM volume/FR | 1.35 | 17.4 | Yes | 40 | ↓ |

| Yin et al 201537 | 100 | Biphasic | ST × FR | 30 ml; CM : saline = 3 : 7 | 270 | 5.0 | CM volume/FR | 1.35 → 0.41 | 20.7 | Yes | NIL | = |

| Zhang et al 201538 | 80 | Biphasic | 1.0 ml kg−1 | NIL | 300 | 4.0 | CM volume/FR | 1.20 | 18.6 | Yes | NIL | ↑ |

| 100 | Biphasic | 1.0 ml kg−1 | NIL | 300 | 4.0 | CM volume/FR | 1.20 | 21.0 | Yes | 46–55 | ↑ | |

| Zhang et al 201540 | 80 | Biphasic | 50–70 ml | NIL | 370 | 5.0 | 10.0–14.0 | 1.85 | 18.5–25.9 | No | 30–40 | ↑ |

| 100 | Biphasic | 50–70 ml | NIL | 370 | 5.0 | 10.0–14.0 | 1.85 | 18.5–25.9 | No | 30–40 | ↑ | |

| Cesare et al 201615 | 100 | Biphasic | 60 ml | NIL | 320 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 1.92 | 19.2 | No | 40 | ↑ |

| Durmus et al 201628 | 80 | Biphasic | 0.6 ml kg−1 | NIL | 370 | CM volume/ID | 10.0 | 1.73 | 17.3 | No | Same as first bolus | NR |

| 100 | Biphasic | 0.6 ml kg−1 | NIL | 370 | CM volume/ID | 10.0 | 1.73 | 17.3 | No | Same as first bolus | NR | |

| Iyama et al 201617 | 80 | Uniphasic | 0.6 ml kg−1 | NIL | 370 | CM volume/ID | 12.0 | 1.07 | 12.0 | Yes | NIL | ↑ |

| Mangold et al 201631 | 80 | Biphasic | 60 ml | NIL | 350 | 4.5 | 13.3 | 1.58 | 21.0 | Yes | 50 ml | ↑ |

| 100 | Biphasic | 80 ml | NIL | 350 | 4.5 | 17.8 | 1.58 | 28.0 | No | 50 ml | ↑ | |

| Pan et al 201634 | 100 | Biphasic | 0.8 ml kg−1 | NIL | 270 | CM volume/ID | 12.0 | 1.70 | 20.9 | Yes | 30 ml | = |

| Wu et al 201619 | 80 | Biphasic | 60 ml | NIL | 270 | 5.0 | 12.0 | 1.35 | 16.2 | Yes | 40 ml | = |

BMI, body mass index; CM, contrast medium; FR, flow rate; ID, injection duration; IDR, iodine delivery rate; NIL, non-existent; NR, not reported; ST, scanning time; TID, total iodine dose.

↓, lower with low tube voltage tube voltage protocol; ↑, improved with low tube voltage protocol; =, similar with low tube voltage protocol.

Three injection patterns were applied: uniphasic (n = 3), biphasic (n = 16) and triphasic (n = 1). Uniphasic injection involved the administration of a single bolus of undiluted CM. Biphasic injection utilises two boluses; an initial undiluted contrast bolus followed by a diluted contrast bolus or a saline flush. Whereas for triphasic injection, three distinct boluses were used; an initial undiluted contrast bolus followed by a CM and saline mixture, and then completed by a saline flush. Compared to 120 kVp, CM reduction was applied in seven studies at 80 kVp17–19,31,33,38,41 and eight studies at 100 kVp.27,34–39,41 However, only two studies at 80 kVp,18, 19 and five studies at 100 kVp34, 35,37,39,41 reported similar vessel contrast enhancement compared to those at 120 kVp.

In the two studies at 80 kVp, two different methods were used to determine the CM volume for the first bolus; (i) a calculation based on body weight at 0.5 ml kg−1 [CM concentration 370 mg ml−1 and fixed injection duration (ID) 7.5 s] and (ii) a fixed volume of 60 ml [CM concentration 270 mg ml−1, flow rate (FR) 5.0 mls−1 and ID 12.0 s]. In the five studies at 100 kVp, three different methods were used to determine the CM volume for first bolus; a calculation based on (i) body weight of 0.8 ml kg−1 (n = 1) and 1.0 ml kg−1 (n = 2), (ii) BMI (BMI < 22 kg m−2, 45 ml; 22 kg m−2 ≤ BMI < 25 kgm−2, 50 ml) (n = 1) and (iii) the product of scanning time and FR (n = 1). CM concentrations of 270 and 370 mg ml−1 were used in these studies with the FR ranging from 4.0 to 5.0 ml s−1 and ID ranging from 12.0 to 14.0 s. These resulted in IDR of 1.35 to 1.45 g s−1 with TID of 10.9 to 16.2 g at 80 kVp and IDR of 1.08 to 1.70 g s−1 with TID of 18.9 to 20.9 g at 100 kVp.

Suggestions of appropriate scanning techniques and CM administration methods

To propose appropriate scanning techniques in prospectively ECG-triggered low tube voltage CCTA protocol, data from all selected studies were integrated, together with consideration of guidelines set by the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT)42 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Suggested appropriate scanning techniques.

For patient with BMI < 25 kg m−2, the suggested tube voltage is 80 kVp. This was determined based on the highest BMI cut-off point used in the selected studies. The application of ATVS was another method for selecting patients. ATCM software based on default reference or targeted value for CCTA protocol at 80 kVp is suggested for image acquisition.

On the other hand, 100 kVp is suggested for patients with BMI < 30 kg m−2. It was determined by comparing the highest BMI cut-off point used in the selected studies and the SCCT guideline. Besides, CC cut-off point of less than 90 cm is an alternative reference for manual patient selection. ATVS can also be used for automatic selection of patient for 100 kVp. During image acquisition, ATCM based on default reference or targeted value for CCTA protocol at 100 kVp is suggested. Alternatively, tube current can be adapted to BMI or CC measurements.

For image reconstruction, currently available FBP and statistical or hybrid IR can be used in both 80 and 100 kVp. In addition, knowledge-based model IR is suggested to be used at 80 kVp to improve the image quality.

Suggested methods of CM administration for prospectively ECG-triggered low tube voltage CCTA protocol are shown in Figure 3. To achieve a similar vessel contrast enhancement as in 120 kVp, reference IDR of 1.35 to 1.45 g s−1 and TID of 10.9 to 16.2 g are recommended for 80 kVp, whereas the reference IDR of 1.08 to 1.70 g s−1 and TID of 18.9 to 20.9 g are recommended for 100kVp.

Figure 3.

Suggested contrast medium (CM) reduction methods.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of prospectively ECG-triggered low tube voltage CCTA protocol to evaluate the reported dose reductions and preservation of image quality. This systematic review found that low tube voltage protocol could substantially reduce radiation dose and produce good imaging in prospectively ECG-triggered CCTA.

Increased image noise at low tube voltage settings was observed in several studies selected in this survey. Nevertheless, the increase of vessel contrast enhancement at low tube voltage due to an increase of photoelectric effect compensated the SNR and CNR.32 Therefore, in almost all the selected studies, dose reduction was possible without the loss of quantitative and qualitative image quality.

Different quantities for radiation dose, including volume CT dose index (CTDIvol), size-specific dose estimates, PKL and HE, were reported in the selected studies. In this review, the HE was used as the comparative benchmark since most of the studies reported it, together with or without PKL.

Different PKL-to-HE conversion coefficients (0.014, 0.017 and 0.028 mSv∙mGy−1∙cm−1) for chest region were used in the selected studies. The conversion coefficient of 0.017 mSv∙mGy−1∙cm−1 was recommended by the European Commission in 2000, which was later replaced by 0.014 mSv∙mGy−1∙cm−1, as recommended by the European Commission in 2004 and Public Health England (formerly National Radiological Protection Board) in 2005.43–45 It had been reported that these conversion coefficients might underestimate the overall radiation exposure from CCTA imaging.46–48 Subsequently, Gosling et al and Sabarudin et al had suggested that a conversion coefficient of 0.028 mSv.mGy−1 cm−1 would give a better estimation of the HE in cardiac-specific imaging.46, 47 However, there were no guidelines on the appropriate PKL-to-HE conversion coefficient for CCTA to date. Therefore, the most commonly used conversion coefficient of 0.014 mSv∙mGy−1∙cm−1 was used in this review.

The scanning techniques in the studies were presented in three stages to provide a clear picture of performing a low-dose CCTA examination; from patient selection to image acquisition and image reconstruction. For manual patient selection based on BMI measurement, inconsistency was observed with regard to the BMI cut-off points of 80, 100 and 120 kVp, although a guideline was established by SCCT in 2014. According to the guideline, 80 kVp was recommended for performing CCTA in patients with BMI < 18 kg m−2; 100 kVp for patients with BMI < 30 kg m−2; and between 120 and 140 kVp for those classified as obese.42 However, rapid development and emerging capabilities of CT scan technology might cause inconsistencies in the voltage parameters. The newer machines used in recent studies would allow for scanning of higher BMI patients at lower CT tube voltage. For instance, Pan et al reported a similar quantitative and qualitative image quality in obese patients with BMI > 30 kg m−2 at 100 kVp.34 Hence, the guideline might need to be reviewed to eliminate inconsistencies among studies which made it difficult to draw conclusions in most of the cases.

Ghoshhajra et al reported a significant correlation between BMI and CC. The author suggested CC as a better parameter because BMI might not provide an exact estimation of body mass at heart level.49 Although only one selected study applied CC as the reference parameter for manual patient selection and tube current adaptation, the reported result was promising at 100 kVp with 38% reduction in HE, improvement in quantitative image quality and similar qualitative image quality.30 Other parameters which were not included in this review, including the measurement of chest dimensions,50 chest tissue composition,51 scout image attenuation52 and unenhanced attenuation53 have also been proposed for manual tube voltage selection. However, those measurements were more complex and prone to errors.28

Compared with manual selection techniques, ATVS is a fully-automated algorithm that utilises CNR as the image quality index to adjust the CT tube voltage based on patients’ size and attenuation characteristics estimated from topograms.54 Patient-specific tube current curves are generated for all tube voltage levels to achieve the desired CNR with the selected scan range on the patients’ topogram. These patient-specific tube current curves are then used to calculate the estimated radiation dose for all tube voltage levels to determine the optimal dose efficiency. Subsequently, the software suggests the best tube voltage setting by taking into account the optimal dose efficiency and limitation of the scanner, such as the maximum tube current and heat capacity.54 This systematic review found that a similar image quality at reduced radiation dose level could be achieved in prospectively ECG-triggered low tube voltage CCTA protocol by combining the application of ATVS (Care kV, Siemens Healthcare) and ATCM (CareDose 4D, Siemens Healthcare). In addition, these algorithms had provided a fast and easy way for selecting appropriate scanning parameters in CCTA examination.

ATCM software packages were installed in all CT scanners by manufacturers to reduce the radiation exposure to patients. However, with no set standards, each manufacturer had created their own ways of tube current modulation based on different image quality references. Additionally, as reported in this systematic review, even for the same ATCM software, different references, or targeted values were used in the CCTA protocol. For example, in studies using the Caredose 4D system (Siemens Healthcare), the reference effective tube current-time product of 285, 398 and 400 mAs were used at 80 kVp, whereas 190, 228, 300, 350 and 400 mAs were used at 100 kVp. The reference or targeted values could directly affect the image quality and radiation dose on patients. Therefore, a consensus regarding the default reference or targeted value for CCTA protocol at different tube voltage would be required to reduce the variation in scanning techniques.

In term of image reconstruction, most of the selected studies had investigated the performance of statistical or hybrid IR, while only one study investigated knowledge-based model IR at 80 kVp. IR techniques were used in early CT machines in the 1970s. However, due to its high computational demand and long reconstruction time, the faster and robust FBP method had been widely used in CT scans. Despite its acceptable performance, CT studies using FBP were heavily affected by image noise, especially when radiation dose was reduced.54 With recent improvements in computer processing, using IR as a noise-suppressing technique had become more feasible in clinical setting. For the past 10 years, IR technologies had evolved from image-based denoising procedures to statistical or hybrid IR, before becoming model based IR and to the latest knowledge-based model IR.55–58 Knowledge-based model IR was expected to decrease the radiation dose even further. A selected study had observed improvement in quantitative image quality at 80 kVp, where there was a 78% dose reduction compared to 120 kVp. Future research should be conducted to investigate the potential of knowledge-based model IR algorithm.

Several prior systematic reviews had been conducted to assess the reduction of HE with IR in CCTA.55–58 These previous reviews mainly focused on the comparison of HE between IR and FBP in CCTA. In this present review, we have further reported the median HE for IR and FBP at different tube voltages. The median HE was found to be lower in studies which applied IR at 80 and 120 kVp. However, a conflicting result was observed at 100 kVp, possibly due to the small number of studies.

Nevertheless, it is always feasible to reduce the radiation dose at the expenses of image quality. The effects on SNR can be masked by the use of IR techniques. There is a great heterogeneity in image reconstruction algorithms used in the included studies. Besides, the focus of these studies is on image quality, rather than diagnostic accuracy. Therefore, findings in this reported review need to be interpreted with caution.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, we excluded many articles due to strict selection criteria. By only including studies comparing prospectively ECG-triggered CCTA protocol at low tube voltages to 120 kVp, it was possible to assess the achievable dose reduction and image quality. Second, although this review suggested appropriate scanning techniques and CM administration methods, nonetheless, these are based on previous findings. Hence, a continuous effort in updating these suggestions is needed to keep pace with the development of CT technology and clinical research findings.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides an overview of currently available scanning techniques used in prospectively ECG-triggered low tube voltage CCTA protocol. This review found that radiation doses could be reduced between 38 to 83% at 80 kVp, and 3 to 80% at 100 kVp without compromising the image quality.

Contributor Information

Sock Keow Tan, Email: fionetsk@yahoo.com.

Chai Hong Yeong, Email: chyeong@um.edu.my.

Raja Rizal Azman Raja Aman, Email: rizalazman@ummc.edu.my.

Kwan Hoong Ng, Email: ngkh@ummc.edu.my.

Yang Faridah Abdul Aziz, Email: yangf@ummc.edu.my.

Kok Han Chee, Email: drcheekh@gmail.com.

Zhonghua Sun, Email: Z.sun@exchange.curtin.edu.au.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dewey M. Clinical indications : Dewey M, Coronary CT angiography. Berlin, Heidelberg: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, Mark D, Min J, O’Gara P, et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56: 1864–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oda S, Utsunomiya D, Funama Y, Awai K, Katahira K, Nakaura T, et al. A low tube voltage technique reduces the radiation dose at retrospective ECG-gated cardiac computed tomography for anatomical and functional analyses. Acad Radiol 2011; 18: 991–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abada HT, Larchez C, Daoud B, Sigal-Cinqualbre A, Paul JF. MDCT of the coronary arteries: feasibility of low-dose CT with ECG-pulsed tube current modulation to reduce radiation dose. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006; 186(6_supplement_2): S387–S390. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hausleiter J, Meyer TS, Martuscelli E, Spagnolo P, Yamamoto H, Carrascosa P, et al. Image quality and radiation exposure with prospectively ECG-triggered axial scanning for coronary CT angiography: the multicenter, multivendor, randomized PROTECTION-III study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012; 5: 484–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Z, Ng KH. Prospective versus retrospective ECG-gated multislice CT coronary angiography: a systematic review of radiation dose and diagnostic accuracy. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: e94–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lell M, Marwan M, Schepis T, Pflederer T, Anders K, Flohr T, et al. Prospectively ECG-triggered high-pitch spiral acquisition for coronary CT angiography using dual source CT: technique and initial experience. Eur Radiol 2009; 19: 2576–2583. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1558-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkadhi H. Radiation dose of cardiac CT-what is the evidence? Eur Radiol 2009; 19: 1311–5. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1312-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leschka S, Kim CH, Baumueller S, Stolzmann P, Scheffel H, Marincek B, et al. Scan length adjustment of CT coronary angiography using the calcium scoring scan: effect on radiation dose. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010; 194: W272–W277. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Royal College of Radiologists. Standards of practice of computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) in adult patients. 2014. Available from: http://www.rcr.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publication/BFCR14%2816%29_CTCA.pdf.

- 11.Mihl C, Maas M, Turek J, Seehofnerova A, Leijenaar RT, Kok M, et al. Contrast media administration in coronary computed tomography angiography - a systematic review. Rofo 2017; 189: 312–25. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-121609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreini D, Mushtaq S, Conte E, Segurini C, Guglielmo M, Petullà M, et al. Coronary CT angiography with 80 kV tube voltage and low iodine concentration contrast agent in patients with low body weight. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2016; 10: 322–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blankstein R, Bolen MA, Pale R, Murphy MK, Shah AB, Bezerra HG, et al. Use of 100 kV versus 120 kV in cardiac dual source computed tomography: effect on radiation dose and image quality. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2011; 27: 579–86. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9683-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao JX, Wang YM, Lu JG, Zhang Y, Wang P, Yang C. Radiation and contrast agent doses reductions by using 80-kV tube voltage in coronary computed tomographic angiography: a comparative study. Eur J Radiol 2014; 83: 309–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Cesare E, Gennarelli A, Di Sibio A, Felli V, Perri M, Splendiani A, et al. 320-row coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) with automatic exposure control (AEC): effect of 100 kV versus 120 kV on image quality and dose exposure. Radiol Med 2016; 121: 618–25. doi: 10.1007/s11547-016-0643-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagarina NV, Irwan R, Gordina G, Fominykh E, Sijens PE. Image quality in reduced-dose coronary CT angiography. Acad Radiol 2011; 18: 984–90. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyama Y, Nakaura T, Yokoyama K, Kidoh M, Harada K, Oda S, et al. Low-contrast and low-radiation dose protocol in cardiac computed tomography: usefulness of low tube voltage and knowledge-based iterative model reconstruction algorithm. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2016; 40: 941–7. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakaura T, Kidoh M, Sakaino N, Utsunomiya D, Oda S, Kawahara T, et al. Low contrast- and low radiation dose protocol for cardiac CT of thin adults at 256-row CT: usefulness of low tube voltage scans and the hybrid iterative reconstruction algorithm. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 29: 913–23. doi: 10.1007/s10554-012-0153-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Q, Wang Y, Kai H, Wang T, Tang X, Wang X, et al. Application of 80-kVp tube voltage, low-concentration contrast agent and iterative reconstruction in coronary CT angiography: evaluation of image quality and radiation dose. Int J Clin Pract 2016; 70(Suppl 9B): B50–B55. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aschoff AJ, Catalano C, Kirchin MA, Krix M, Albrecht T. Low radiation dose in computed tomography: the role of iodine. Br J Radiol 2017; 90: 20170079. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edyvean S, Lewis M, Britten A. Radiation dose metrics and the effect of CT scan protocol parameters : Tack D, Kalra M, Gevenois P, Radiation dose from multidetector CT. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae KT. Intravenous contrast medium administration and scan timing at CT: considerations and approaches. Radiology 2010; 256: 32–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10090908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakaura T, Awai K, Maruyama N, Takata N, Yoshinaka I, Harada K, et al. Abdominal dynamic CT in patients with renal dysfunction: contrast agent dose reduction with low tube voltage and high tube current-time product settings at 256-detector row CT. Radiology 2011; 261: 467–76. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee TY, Chhem RK. Impact of new technologies on dose reduction in CT. Eur J Radiol 2010; 76: 28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015; 4: 1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alkadhi H, Stolzmann P, Scheffel H, Desbiolles L, Baumüller S, Plass A, et al. Radiation dose of cardiac dual-source CT: the effect of tailoring the protocol to patient-specific parameters. Eur J Radiol 2008; 68: 385–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durmus T, Luhur R, Daqqaq T, Schwenke C, Knobloch G, Huppertz A, et al. Individual selection of X-ray tube settings in computed tomography coronary angiography: reliability of an automated software algorithm to maintain constant image quality. Eur J Radiol 2016; 85: 963–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan AN, Khosa F, Shuaib W, Nasir K, Blankstein R, Clouse M. Effect of tube voltage (100 vs. 120 kVp) on radiation dose and image quality using prospective gating 320 row multi-detector computed tomography angiography. J Clin Imaging Sci 2013; 3: 62. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.124092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu C, Wang Z, Ji J, Wang H, Hu X, Chen C. Evaluation of a chest circumference-adapted protocol for low-dose 128-slice coronary CT angiography with prospective electrocardiogram triggering. Korean J Radiol 2015; 16: 13–20. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.1.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mangold S, Wichmann JL, Schoepf UJ, Poole ZB, Canstein C, Varga-Szemes A, et al. Automated tube voltage selection for radiation dose and contrast medium reduction at coronary CT angiography using 3rd generation dual-source CT. Eur Radiol 2016; 26: 3608–16. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4191-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakaura T, Kidoh M, Sakaino N, Nakamura S, Nozaki T, Izumi A, et al. Low radiation dose protocol in cardiac CT with 100 kVp: usefulness of display preset optimization. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 29: 1381–9. doi: 10.1007/s10554-013-0214-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oda S, Utsunomiya D, Yuki H, Kai N, Hatemura M, Funama Y, et al. Low contrast and radiation dose coronary CT angiography using a 320-row system and a refined contrast injection and timing method. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2015; 9: 19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan YN, Li AJ, Chen XM, Wang J, Ren DW, Huang QL. Coronary computed tomographic angiography at low concentration of contrast agent and low tube voltage in patients with obesity: a feasibility study. Acad Radiol 2016; 23: 438–45. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen Y, Fan Z, Sun Z, Xu L, Li Y, Zhang N, et al. High pitch dual-source whole aorta CT angiography in the detection of coronary arteries: a feasibility study of using iodixanol 270 and 100 kVp with iterative reconstruction. J Med Imaging Health Inform 2015; 5: 117–25. doi: 10.1166/jmihi.2015.1367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun G, Hou YB, Zhang B, Yu L, Li SX, Tan LL, et al. Application of low tube voltage coronary CT angiography with low-dose iodine contrast agent in patients with a BMI of 26-30 kg/m2. Clin Radiol 2015; 70: 138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin WH, Lu B, Gao JB, Li PL, Sun K, Wu ZF, et al. Effect of reduced x-ray tube voltage, low iodine concentration contrast medium, and sinogram-affirmed iterative reconstruction on image quality and radiation dose at coronary CT angiography: results of the prospective multicenter REALISE trial. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2015; 9: 215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang C, Yu Y, Zhang Z, Wang Q, Zheng L, Feng Y, et al. Imaging quality evaluation of low tube voltage coronary CT angiography using low concentration contrast medium. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0120539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang C, Zhang Z, Yan Z, Xu L, Yu W, Wang R. 320-row CT coronary angiography: effect of 100-kV tube voltages on image quality, contrast volume, and radiation dose. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2011; 27: 1059–68. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9754-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Kang S, Han D, Xie X, Deng Y. Application of intelligent optimal kV scanning technology (CARE kV) in dual-source computed tomography (DSCT) coronary angiography. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8: 17644–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng M, Liu Y, Wei M, Wu Y, Zhao H, Li J. Low concentration contrast medium for dual-source computed tomography coronary angiography by a combination of iterative reconstruction and low-tube-voltage technique: feasibility study. Eur J Radiol 2014; 83: e92–e99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raff GL, Chinnaiyan KM, Cury RC, Garcia MT, Hecht HS, Hollander JE, et al. SCCT guidelines on the use of coronary computed tomographic angiography for patients presenting with acute chest pain to the emergency department: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2014; 8: 254–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jessen KA, Panzer W, Shrimpton PC. European guidelines on quality criteria for computed tomography. Brussels, Belgium: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shrimpton P. European guidelines for multislice computed tomography funded by the European Commission 2004: contract number FIGMCT2000-20078-CTTIP. Luxembourg; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shrimpton PC, Hillier MC, Lewis MA, Dunn M. Doses from computed tomography (CT) examinations in the UK: 2003 review Report No: NRPB-W67 Chilton, UK: The British Institute of Radiology.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gosling O, Loader R, Venables P, Rowles N, Morgan-Hughes G, Roobottom C. Cardiac CT: are we underestimating the dose? A radiation dose study utilizing the 2007 ICRP tissue weighting factors and a cardiac specific scan volume. Clin Radiol 2010; 65: 1013–7. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sabarudin A, Sun Z, Ng KH. Radiation dose in coronary CT angiography associated with prospective ECG-triggering technique: comparisons with different CT generations. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2013; 154: 301–7. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncs243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan SK, Yeong CH, Ng KH, Abdul Aziz YF, Sun Z. Recent update on radiation dose assessment for the state-of-the-art coronary computed tomography angiography protocols. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0161543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghoshhajra BB, Engel LC, Major GP, Verdini D, Sidhu M, Károlyi M, et al. Direct chest area measurement: a potential anthropometric replacement for BMI to inform cardiac CT dose parameters? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2011; 5: 240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogalla P, Blobel J, Kandel S, Meyer H, Mews J, Kloeters C, et al. Radiation dose optimisation in dynamic volume CT of the heart: tube current adaptation based on anterior-posterior chest diameter. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2010; 26: 933–40. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9630-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paul NS, Kashani H, Odedra D, Ursani A, Ray C, Rogalla P. The influence of chest wall tissue composition in determining image noise during cardiac CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197: 1328–34. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao J, Li J, Earls J, Li T, Wang Q, Dai R. Individualized tube current selection for 64-row cardiac CTA based on analysis of the scout view. Eur J Radiol 2011; 79: 266–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paul JF. Individually adapted coronary 64-slice CT angiography based on precontrast attenuation values, using different kVp and tube current settings: evaluation of image quality. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2011; 27(Suppl 1): 53–9. doi: 10.1007/s10554-011-9960-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee KH, Lee JM, Moon SK, Baek JH, Park JH, Flohr TG, et al. Attenuation-based automatic tube voltage selection and tube current modulation for dose reduction at contrast-enhanced liver CT. Radiology 2012; 265: 437–47. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Armstrong I, Trevor M, Widdowfield M. Maintaining image quality and reducing dose in prospectively-triggered CT coronary angiography: a systematic review of the use of iterative reconstruction. Radiography 2016; 22: 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2015.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Den Harder AM, Willemink MJ, De Ruiter QM, De Jong PA, Schilham AM, Krestin GP, et al. Dose reduction with iterative reconstruction for coronary CT angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Radiol 2016; 89: 20150068. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.den Harder AM, Willemink MJ, de Ruiter QM, Schilham AM, Krestin GP, Leiner T, et al. Achievable dose reduction using iterative reconstruction for chest computed tomography: a systematic review. Eur J Radiol 2015; 84: 2307–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shammakhi AA, Sun Z. Coronary CT angiography with use of iterative reconstruction algorithm in coronary stenting: a systematic review of image quality, diagnostic value and adiation dose. J Med Imaging Health Inform 2015; 5: 103–9. doi: 10.1166/jmihi.2015.1365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]