Abstract

Objectives:

To describe the demographic and practice characteristics of the clinicians enrolled in a large, prospective cohort study examining recommendations and treatment for adult anterior open bite (AOB) and the relationship between these characteristics and practitioners' self-reported treatment preferences. The characteristics of the AOB patients recruited were also described.

Materials and Methods:

Practitioners were recruited from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Participants in the study consisted of practitioners and their adult AOB patients in active treatment. Upon enrollment, practitioners completed questionnaires enquiring about demographics, treatment preferences for adult AOB patients, and treatment recommendations for each patient. Patients completed questionnaires on demographics and factors related to treatment.

Results:

Ninety-one practitioners and 347 patients were recruited. Demographic characteristics of recruited orthodontists were similar to those of American Association of Orthodontists members. The great majority of practitioners reported using fixed appliances and elastics frequently for adult AOB patients. Only a third of practitioners reported using aligners frequently for adult AOB patients, and 10% to 13% frequently recommended temporary anchorage devices (TADs) or orthognathic surgery. Seventy-four percent of the patients were female, and the mean age was 31.4 years. The mean pretreatment overbite was −2.4 mm, and the mean mandibular plane angle was 38.8°. Almost 40% of patients had undergone orthodontic treatment previously.

Conclusions:

This article presents the demographic data for 91 doctors and 347 adult AOB patients, as well as the practitioners' self-reported treatment preferences.

Keywords: Anterior open bite, Network study, Practitioner demographics, Open bite, Patient demographics

INTRODUCTION

Anterior open bite (AOB) was first described in the dental literature more than 150 years ago.1 Generally, it can be defined as the absence of vertical overlap of the anterior teeth.2 AOB prevalence has been reported to range from 0.6% to 16.5%,3 depending on age and race. Despite its relatively low overall prevalence, it has been estimated that approximately 17% of orthodontic patients with skeletal malocclusions have AOB.4

The treatment of AOB may vary based on a patient's age. In children, early conservative interventions may improve or completely resolve AOB.5 In adults, because growth is complete and functional patterns are well established, correcting the malocclusion is often challenging, and both orthodontic and surgical methods have been employed.

Orthodontic treatment for AOB may emphasize either intrusion of the molars or extrusion of the incisors. The multiloop edgewise archwire (MEAW) with anterior vertical elastics is an example of a technique that claims to address both.6 Clear aligners have also been suggested for AOB patients because the double thickness of plastic on the occlusal surface may exert an intrusive force on the posterior teeth.7 Extractions of first premolars can improve incisor vertical relationships via the “drawbridge effect,” whereby the bite is deepened by retroclining and extruding incisors during retraction.8 Alternatively, extraction of second premolars or molars may allow the overbite to deepen as posterior teeth move mesially during space closure (the “wedge effect”).9

Various surgical procedures have been used to close open bites. Historically, maxillary impaction has been popular10 but may result in adverse soft tissue effects.11 More recently, mandibular bilateral sagittal split osteotomy with closing surgical rotation has been used. Advantages include allowing correction of mandibular anteroposterior skeletal discrepancies and avoidance of adverse soft tissue effects.12

While surgical correction has typically been recommended to adults with severe open bites,13 recent case reports have illustrated successful correction of significant open bites in adults using other techniques, including aligners,7 MEAW with elastics,14 and TADs.15 This has resulted in confusion regarding the outcomes that may be routinely expected with these various techniques. Thus, in 2015, the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) Adult Anterior Openbite Study was launched. The National Dental PBRN is a consortium of dental practices focused on improving the scientific basis for clinical decision making.16 Detailed information is available on their website (http://www.nationaldentalpbrn.org). The American Association of Orthodontists (AAO) vetted the study topic and design and assisted with recruiting practitioners.

The purpose of this study was to explore treatment recommendations, outcomes, and subsequent vertical stability of adult AOB patients. The study was divided into three phases: enrollment, end of treatment, and 1-year posttreatment. This first article describes the demographic and practice characteristics of the clinicians enrolled in the study and the relationship between these characteristics and their self-reported treatment preferences. This article also describes the characteristics of the AOB patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dental providers were recruited from the National Dental PBRN. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval to conduct this study was obtained from institutions representing the various regions of the network. They included the University of Alabama Institutional Review Board (acting as the central IRB), the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Institutional Review Board (for the Western region), and the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board (for the Northeast region).

Inclusion Criteria for Practitioners

Orthodontist or dentist that routinely performs orthodontic treatment.

Expects to recruit three to eight adult patients in active treatment for AOB and expects to complete treatment within 24 months of enrollment.

Routinely takes cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

Has the ability to upload deidentified cephs and intraoral photographs to a central data repository.

Affirms that the practice can devote sufficient time to recording required data.

Does not anticipate retiring, selling, or moving during the study.

Inclusion Criteria for Patients

At least 18 years of age at time of enrollment.

One or more incisors with no vertical overlap. The remaining incisors may have incisor overlap but could not contact teeth in the opposing arch.

In active treatment for AOB and expects to have treatment completed within 24 months of enrollment.

Initial cephalometric radiograph taken prior to beginning treatment.

Exclusion Criteria for Patients

Had clefts, craniofacial anomalies, or syndromes affecting the face.

Had a significant physical/mental condition that would affect the ability to complete a questionnaire.

The population was restricted to adults to eliminate facial growth as a potential variable affecting treatment outcome. To reduce selection bias, participating orthodontists were requested to enroll all of their adult open-bite patients in active treatment (up to 15 subjects per provider).

A study description, informed consent, and questionnaires were provided to enrolled practitioners and their patients. Patients were reimbursed for each phase of the study: $25 for the first, $25 for the second, and $50 for the third phase. Practitioners were reimbursed $100 per enrolled patient per phase ($300/patient total). Each practitioner was asked to fill out a practitioner characteristics form at enrollment, which included questions about demographics and their preferred techniques for treating adult open-bite patients. AOB patients who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study either at their regular adjustment visits or over the phone. Once a patient was enrolled, the orthodontist was asked to complete a form for each patient, providing chief complaint, goals, expectations, prior treatment, treatment recommended, and final treatment plan accepted. Orthodontists were also asked about patient dentofacial characteristics, such as spacing, crowding, Angle classification, crossbites, and so forth. At the time of enrollment, patients were given a questionnaire that asked about their demographics, chief complaints, treatment goals, and reasons for selecting a certain treatment plan. Questionnaires were collected centrally, and National Network staff entered all data. The study questionnaires can be viewed at this URL: http://nationaldentalpbrn.org/study-results/anterior-openbite-malocclusions-in-adult-recommendations-treatment-and-stability.htm.

Pretreatment cephs and frontal intraoral photos were acquired for each patient and forwarded to the research team at the University of Washington. The deidentified cephs were imported into Dolphin imaging software (version 11.0; Dolphin Imaging and Management Solutions, Chatsworth, Calif), landmarks were identified, and measurements were performed using a custom analysis in Dolphin. Cephalometric landmarks were first identified by a single experienced examiner at the University of Washington and then reviewed by a second examiner. Disagreements over landmark identification were resolved by means of a consensus between the two examiners. Both examiners underwent training and calibration prior to identification of landmarks on study images. In addition, a random selection of 10 cephs from the study pool was digitized twice, 1 month apart, by both examiners to determine inter- and intrarater reliability. Inter- and intraexaminer reliability was assessed with an intraclass correlation coefficient. All values were greater than 0.90, indicating that tracings were reliable both by one practitioner over time and between practitioners.

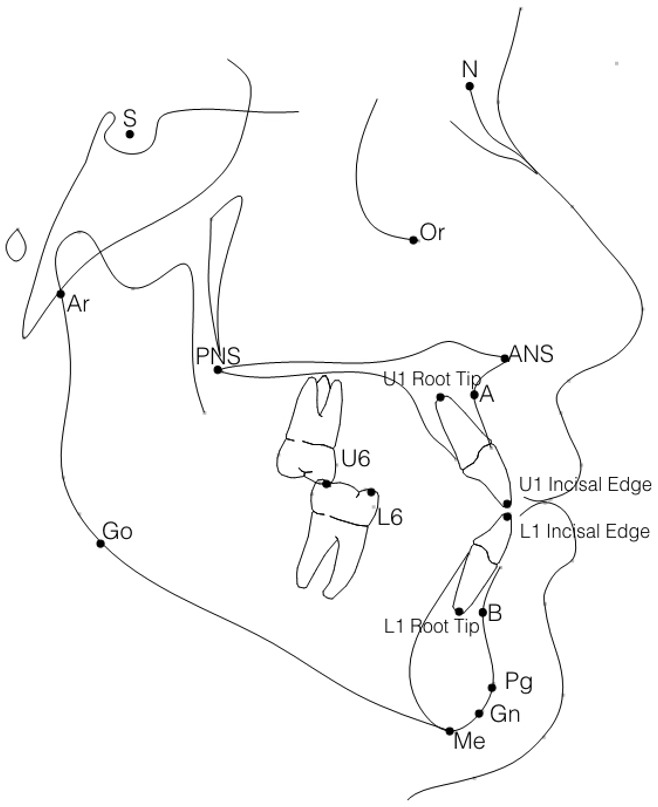

The standard orthodontic landmarks that were identified included the following points (Figure 1): sella (S), nasion (N), anterior nasal spine (ANS), posterior nasal spine (PNS), pogonion (Pg), gnathion (Gn), menton (Me), anatomic gonion (Go), articulare (Ar), A-Point (A), B-Point (B), the incisal edges of the maxillary and mandibular incisor teeth, the root tips of the maxillary and mandibular incisors, and the mesiobuccal cusp tips of the maxillary and mandibular first molars.

Figure 1.

Cephalometric landmarks identified on pre-intervention lateral cephalograms: sella (S), nasion (N), anterior nasal spine (ANS), posterior nasal spine (PNS), pogonion (Pg), gnathion (Gn), menton (Me), anatomic gonion (Go), articulare (Ar), A-Point (A), B-Point (B), incisal edge of the mandibular incisor (L1 incisal edge), incisal edge of the maxillary incisor (U1 incisal edge), root tip of the maxillary incisor (U1 root tip), root tip of the mandibular incisor (L1 root tip), mesiobuccal cusp tip of the maxillary first molar (U6), mesiobuccal cusp tip of the mandibular first molar (L6).

A standard millimetric ruler in the forehead positioner of the cephalostat was used to calibrate millimetric measurements. When a ruler was absent, a ruler was generated using an estimate of the mesiodistal width of the mandibular first molar (n = 51). To determine an appropriate molar width estimate, 20 casts were chosen at random from patient files at the University of Washington Orthodontic clinic, and the mandibular first molars were measured on the casts with digital calipers. An average molar width was calculated from these measurements to be 11.5 mm, which was considered a reasonable estimate across different ages, sexes, and ethnicities based on similar averages reported in the odontometric literature for mandibular molar widths in American populations.17,18

Data Analysis

Practitioner training, demographics, practice characteristics, and experience were described, as were treatment preferences. Four main treatment groups were identified for primary examination: aligners, extractions, temporary anchorage devices (TADs), and orthognathic surgery. The relationship between practitioner characteristics and the frequent use of these treatment approaches were explored with chi-square and Fisher exact test. The demographics of enrolled patients were described. All analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS v9.4, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Practitioners

A total of 91 practitioners were recruited from October 2015 through June 2016 (Table 1). Participating practitioners were well-distributed across different age groups and experience levels. The mean age of practitioners was 49 (SD = 10) years, and the range was from 31 to 68 years. The mean years since graduating from dental school was 22 (SD = 10), and the range was from 3 to 43 years. Ninety-seven percent of the practitioners were orthodontists, and 74% were male. Most practitioners were Caucasian (62%), with the next largest group being Asian (24%). Most (85%) were from private practice settings, either as a solo practitioner (54%), owner of a nonsolo practice (20%), or as an associate (10%). The remaining participants were from academic settings (12%) or managed care settings (3%). Participating practices were located across the United States, with most from the Western and Southwestern regions.

Table 1.

Practitioner Demographicsa

| n |

% |

|

| Status | ||

| Orthodontist | 88 | 97 |

| General practitioner | 3 | 3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 67 | 71 |

| Female | 24 | 26 |

| Age, years | ||

| <45 | 35 | 38 |

| 45–54 | 26 | 29 |

| 55–64 | 23 | 25 |

| ≥65 | 7 | 8 |

| Years since graduated dental school (N = 90) | ||

| <10 years | 10 | 11 |

| 10–19 years | 34 | 38 |

| 20–29 years | 25 | 28 |

| 30+ years | 21 | 23 |

| Race and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (N = 90) | ||

| Non-Hispanic white/Caucasian | 56 | 62 |

| Asian | 22 | 24 |

| Multirace | 2 | 2 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 | 11 |

| Black/African American | 0 | 0 |

| Practice type (N = 89) | ||

| Solo, private practice | 48 | 54 |

| Owner, nonsolo, private practice | 18 | 20 |

| Academic setting | 11 | 12 |

| Associate/employee of private practice | 9 | 10 |

| HealthPartners/Permanente Dental Associates | 2 | 2 |

| Other managed care | 1 | 1 |

| Practice location (N = 88) | ||

| Inner city of urban area | 15 | 17 |

| Urban (not inner city) | 31 | 35 |

| Suburban | 34 | 39 |

| Rural | 8 | 9 |

| Geographic region of practice | ||

| West (Alaska, Ark, Calif, Colo, Guam, Hawaii, Ida, Mont, Nev, MP, Ore, Utah, Wash, Wyo) | 37 | 41 |

| Midwest (Ill, Ind, Ia, Mich, Minn, Neb, ND, Ohio, SD, Wis) | 9 | 10 |

| Southwest (Ariz, Kans, NM, Okla, Tex) | 16 | 18 |

| South Central (Ala, Ark, Ky, La, Miss, Mo, Tenn, WVa) | 6 | 7 |

| South Atlantic (Fla, Ga, NC, SC, Va) | 9 | 10 |

| Northeast (Conn, Del, DC, Maine, Md, Mass, NH, NJ, NY, Pa, PR, RI, VI, Vt) | 14 | 15 |

N = 91 unless indicated.

The practitioners' self-reported treatment strategies for adult AOB patients are reported in Table 2. Fixed appliances were employed frequently by almost all practitioners. The use of aligners was variable, with 19% never using them and 33% reporting frequent use.

Table 2.

Practitioner-Reported Frequency of Treatments for Adult AOB Patients (N = 91)

| Treatment |

Not at All |

Occasionally |

Often |

|||

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

| Fixed appliances | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 86 | 95 |

| Clear aligners | 17 | 19 | 44 | 48 | 30 | 33 |

| Maxillary arch extraction | 6 | 7 | 59 | 65 | 26 | 28 |

| Mandibular arch extraction | 7 | 8 | 58 | 64 | 25 | 28 |

| TAD mini-screws | 23 | 26 | 56 | 62 | 11 | 12 |

| TAD mini-plates | 64 | 71 | 25 | 28 | 1 | 1 |

| Maxillary jaw surgery | 6 | 7 | 73 | 80 | 12 | 13 |

| Mandibular jaw surgery | 12 | 13 | 70 | 77 | 9 | 10 |

| Tongue or thumb crib | 20 | 22 | 51 | 56 | 20 | 22 |

| Speech therapy | 45 | 49 | 36 | 40 | 10 | 11 |

| Occlusal equilibrium | 26 | 29 | 50 | 56 | 14 | 16 |

| Elastics | 0 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 80 | 88 |

| Interproximal reduction | 3 | 3 | 51 | 57 | 36 | 40 |

| Maxillary expansion | 4 | 4 | 52 | 57 | 35 | 38 |

| Headgear | 47 | 52 | 30 | 33 | 13 | 14 |

| Corticotomy | 69 | 78 | 19 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Vibration | 66 | 73 | 21 | 23 | 3 | 3 |

| Tongue exercises | 88 | 97 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Splint/bite block | 87 | 96 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Other treatment | 86 | 95 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

Extractions in the upper and lower arch were a common strategy for 28% of the practitioners. TAD mini-screws and orthognathic surgery were recommended often by 10%–13% of the practitioners.

Elastics, interproximal reduction, and maxillary expansion were used occasionally or often by almost all practitioners. On the other hand, accelerated orthodontic techniques, such as corticotomy and vibration, were less commonly used, with 79% never using corticotomy and 73% never using vibration techniques.

The relationship between practitioner demographic factors and the likelihood to recommend aligners, extractions, TADs, and orthognathic surgery was also evaluated (Table 3). Fixed appliances were not included in these analyses, as they were used often by 93% of the practitioners.

Table 3.

Relationship Between Primary Treatments and Practitioner Demographics (N = 91)a

| Aligners Often |

Extract Often |

TADS Often |

Jaw Surgery Often |

|||||

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

| Specialty | ||||||||

| Orthodontist (n = 88) | 29 | 33 | 26 | 29 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 15 |

| General practitioner (n =3) | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P = .4 | P = .6 | P = .7 | P = .6 | |||||

| Country attended dental school | ||||||||

| United States (n = 78) | 25 | 32 | 19 | 24 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 12 |

| Other (n = 13) | 5 | 38 | 7 | 54 | 5 | 38 | 4 | 31 |

| P = .8 | P = .04 | P = .008 | P = .09 | |||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male (n = 67) | 17 | 25 | 21 | 31 | 8 | 12 | 10 | 15 |

| Female (n = 24) | 13 | 54 | 5 | 21 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 12 |

| P = .02 | P = .4 | P = .9 | P = .9 | |||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| <45 (n = 35) | 13 | 37 | 16 | 46 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 11 |

| 45–54 (n = 26) | 9 | 35 | 6 | 23 | 5 | 19 | 2 | 82 |

| 55–64 (n = 23) | 5 | 22 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 26 |

| 65 and older (n = 7) | 3 | 43 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 29 |

| P = .6 | P = .03 | P = .6 | P = .3 | |||||

| Race and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | ||||||||

| White/Caucasian (n = 56) | 17 | 30 | 11 | 20 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 13 |

| Asian (n = 22) | 10 | 45 | 10 | 45 | 6 | 27 | 3 | 14 |

| Multirace (n = 2) | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Hispanic/Latino (n = 10) | 2 | 20 | 4 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 20 |

| P = .4 | P = .06 | P = .02 | P = .6 | |||||

| Practice experience | ||||||||

| Years since graduated dental school | ||||||||

| <10 (n = 10) | 5 | 50 | 4 | 40 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 10–19 (n = 34) | 11 | 32 | 14 | 41 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 12 |

| 20–29 (n = 25) | 10 | 40 | 5 | 20 | 6 | 24 | 5 | 20 |

| 30+ (n = 21) | 4 | 19 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 19 |

| P = .3 | P = .10 | P = .2 | P = .4 | |||||

P values from chi-square or Fisher exact test.

With respect to practitioner type, no general dentists reported employing extractions, TADs, or surgery often. Orthodontists who attended dental school outside the United States were more likely to recommend extractions and TADs more often, even though 88 of 89 received their orthodontic education in the United States. There was no significant difference between groups prescribing TADs, surgery, or extractions often on the basis of their gender. However, female orthodontists were more likely to use aligner therapy than male orthodontists.

There was a trend in extraction rates based on age. More practitioners in the youngest age group prescribed extractions compared with the older age groups. There was also a difference noted in TAD usage by practitioner race. Only 7% of Caucasian providers and 0% of Hispanic providers often prescribed TADs, while 27% of Asian practitioners and 50% of multirace practitioners reported that they often prescribe TADs for open-bite correction. When practice experience was examined to determine how it affected treatment-planning trends, no significant differences were found in the percentage of practitioners preferring extractions, TADs, or surgical plans based on their years since dental school.

Practice characteristics were associated with some recommendation patterns. For example, extractions were much more commonly recommended by employee orthodontists and those in academic settings (Table 4). Those in academic settings also had a higher rate of recommending TADs. Although not statistically significant, practitioners in inner-city areas reported the highest frequency of TAD recommendations.

Table 4.

Relationship Between Primary Treatments and Practice Demographicsa

| Aligners Often |

Extract Often |

TADS Often |

Jaw Surgery Often |

|||||

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

| Practice type | ||||||||

| Solo, private practice (n = 48) | 18 | 37 | 10 | 21 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Owner, nonsolo, private practice (n = 18) | 4 | 22 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| Associate/employee private practice (n = 9) | 4 | 44 | 5 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| Academic setting (n = 11) | 3 | 21 | 6 | 55 | 5 | 45 | 3 | 27 |

| P = .6 | P = .01 | P = .01 | P = .3 | |||||

| Location of primary practice location | ||||||||

| Inner city of urban area (n = 15) | 8 | 53 | 6 | 40 | 5 | 33 | 3 | 20 |

| Urban (not inner city) (n = 31) | 11 | 35 | 9 | 29 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 13 |

| Suburban (n = 34) | 9 | 26 | 10 | 29 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 15 |

| Rural (n = 8) | 1 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P = .4 | P = .6 | P = .7 | P = .6 | |||||

| Network region | ||||||||

| Western (n = 37) | 16 | 43 | 7 | 19 | 5 | 14 | 5 | 14 |

| Midwest (n = 9) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 11 |

| Southwest (n = 16) | 7 | 44 | 6 | 38 | 3 | 191 | 2 | 12 |

| South Central (n = 6) | 1 | 17 | 2 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 33 |

| South Atlantic (n = 9) | 2 | 22 | 2 | 33 | 2 | 22 | 2 | 22 |

| Northeast (n = 14) | 4 | 29 | 6 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| P = .12 | P = .5 | P = .5 | P = .7 | |||||

P values from chi-square or Fisher exact test.

Patients

A total of 358 adult patients were initially enrolled between October 2015 and December 2016. Eleven patients were dropped after enrollment because it was determined they did not meet the inclusion criteria. An additional 2 patients were missing structures on the cephalometric radiographs and had only partial cephalometric data. Because of the poor quality of initial cephalometric radiographs, cephalometric data could not be measured for 7 subjects. Thus, the entire sample consisted of 347 eligible subjects, 338 of which had complete cephalometric data. In more than two-thirds of the sample, all four incisors exhibited no vertical overlap (Figure 2). The mean initial overbite was −2.4 mm, and the mean mandibular plane angle (relative to SN) was 38.8° (Figure 3). Thus, most patients enrolled had significant open bites and vertical skeletal patterns.

Figure 2.

Representative anterior open bite of a study patient.

Figure 3.

Lateral cephalogram depicting representative facial characteristics of a study patient.

The sex distribution of patients was 74% female (Table 5). The mean age of patients was 31.4 years (range, 18–71 years). The patient race distribution was 55% Caucasian, 23% Hispanic, 10% African American, 9% Asian, and 3% multirace. A high percentage (75%) of the patients had some dental insurance, and 45% of the patients had dental insurance with some orthodontic coverage. Patients were well-distributed across different education levels: 21% had a high school diploma or less, 32% attended some college or possessed an associate degree, 31% had a bachelor degree, and 17% had a graduate degree. About 40% of the patients had a previous history of orthodontic treatment.

Table 5.

Patient Demographics (N = 347)

| n |

% |

|

| Sex (n = 346) | ||

| Male | 91 | 26 |

| Female | 255 | 74 |

| Age, years (n = 346) | ||

| 18–24 | 118 | 34 |

| 25–34 | 136 | 39 |

| 35+ | 92 | 27 |

| Race and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (n = 343) | ||

| White | 189 | 55 |

| Black/African American | 34 | 10 |

| Asian | 29 | 8 |

| Multirace | 12 | 3 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 79 | 23 |

| Previous orthodontics (n = 346) | ||

| Yes | 136 | 39 |

| No | 210 | 61 |

| Dental insurance (n = 347) | ||

| Any dental insurance | 260 | 75 |

| Dental insurance covers orthodontics | 147 | 45 |

| Dental insurance covers jaw surgery | 40 | 11 |

| Medical insurance covers jaw surgery | 73 | 21 |

| Any insurance covers jaw surgery | 87 | 25 |

| Highest level of education (n = 344) | ||

| High school graduate or less | 71 | 21 |

| Some college or associate's degree | 109 | 32 |

| Bachelor's degree | 107 | 31 |

| Graduate degree | 57 | 17 |

DISCUSSION

This article presents a summary of the open-bite challenge, the rationale for conducting this network study, and the characteristics of the practitioners and patients enrolled. The power of network studies is illustrated by the recruitment of more than 300 adult AOB patients in about 15 months. The National Dental PBRN, funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), provides the dental profession with a tremendous opportunity to investigate important questions with studies that can recruit large numbers of patients, explore multiple outcomes, and provide generalizable results.16 The heterogeneity of practitioners and patients enrolled in the study helps to make these findings generalizable to the population of orthodontists and patients in the United States.

When this practitioner sample was compared with demographic data from the AAO (J. Hittner, AAO librarian, personal correspondence, October 5, 2017), which reports an 88% membership rate across orthodontists in the United States, there were some similarities and some differences. The gender distribution of practitioners in this study was almost identical to the AAO membership: 27% female and 73% male. Among AAO members, about 25% fall into each of the four categories of “years in practice.” However, in this study, the rate of participants with fewer than 10 years of experience (11%) was lower. AAO data indicate that 94% of their members work in private practice, either as owners or associates. In this group of practitioners, 84% worked in private practice settings as owners or associates. Practitioners in academic centers were overrepresented in this study compared with the AAO membership (12% of the doctors in this study, compared with 2% in the AAO).

Practitioners who received their dental training outside of the United States reported prescribing TADs more often than those trained in the United States. This is consistent with findings from a 2008 poll of the AAO members, reporting that foreign orthodontists placed significantly more mini-screws than their US counterparts.19 In addition, this study found that more practitioners of Asian descent reported that they often prescribed TADs for AOB treatment. Mini-screw implants have historically been very popular in Asian countries, where bimaxillary protrusion is common.

While it was hypothesized that younger practitioners would be more likely to prescribe TADs, this was not borne out in the results. If there was any trend, it was that more practitioners who graduated between 20 and 29 years ago reported using TADs more often than did those in the most recent graduation group. Although these older practitioners would not have received formal training with mini-screws, this finding indicates a willingness to adopt new techniques.

This study had several limitations. First, the enrollment of practitioners was not a random process. Rather, practitioners were invited to participate, and because the registration and training procedures took considerable time and effort, some self-selection certainly occurred. Second, the treatment preferences of the practitioners were based on self-reported data. Finally, the analyses conducted between practitioner characteristics and their treatment preferences are intended to be descriptive, rather than inferential. The overall study was not powered for these factors but rather for end-of-treatment and 1-year follow-up outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

This article presents the demographic data for 91 doctors and 347 adult AOB patients, as well as the practitioners' self-reported treatment preferences.

The great majority of orthodontists reported frequent use of fixed appliances for AOB patients.

Only one-third reported using aligners frequently, and TADs and surgery are frequently recommended by about 10%–13% of orthodontists. The enrolled patients were 74% female, with a mean age of 31.4 years. Forty percent reported having prior orthodontic treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by NIDCR grant U19-DE-22516. Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the respective organizations or the National Institutes of Health. The informed consent of all human subjects who participated in this investigation was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been explained fully. An Internet site devoted to details about the nation's network is located at http://NationalDentalPBRN.org and is conducted under the auspices of the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network (NDPBRN).We gratefully acknowledge all the practitioners and patients who made this study possible. We are also grateful to the network's regional coordinators, Sarah Basile, RDH, MPH, Chris Enstad, BS, and Hannah Van Lith, BA (Midwest); Stephanie Hodge, MA, and Kim Stewart (Western); Pat Ragusa (Northeast); Deborah McEdward, RDH, BS, CCRP, and Danny Johnson (South Atlantic); Claudia Carcelén, MPH, Shermetria Massingale, MPH, CHES, and Ellen Sowell, BA (South Central); Stephanie Reyes, BA, Meredith Buchberg, MPH, and Monica Castillo, BA (Southwest). We also thank Kavya Vellala and the Westat Coordinating Center staff, the American Association of Orthodontists (AAO), Jackie Hittner (AAO Librarian), Gregg Gilbert, DDS, MBA (National Network Director), and Dena Fischer, DDS, MSD, MS (NIDCR Program Director).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson GM. Practical Orthodontics. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artese A, Drummond S, Nascimento JMd, Artese F. Criteria for diagnosing and treating anterior openbite with stability. Dental Press J Orthod. 2011;16:136–161. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly JE, Sanchez M, vanKirk LE. An Assessment of the Occlusion of Teeth of Children US Public Health Service DHEW Pub No (HRA)74-1612. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proffit WR, Fields HW, Jr, Moray LJ. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: Estimates from the NHANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1997;13:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subtelny JD, Sakuda M. Open-bite: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1964;50:337–358. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YH, Han UK, Lim DD, Serraon MLP. Stability of anterior openbite correction with multiloop edgewise archwire therapy: a cephalometric follow-up study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:43–54. doi: 10.1067/mod.2000.104830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guarneri MP, Oliverio T, Silvestre I, Lombardo L, Siciliani G. Open bite treatment using clear aligners. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:913–919. doi: 10.2319/080212-627.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janson G, Valarelli FP, Beltro RTS, de Freitas MR, Henriques JFC. Stability of anterior open-bite extraction and nonextraction treatment in the permanent dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:768–774.. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima K, Endo T, Shimooka S. Effects of maxillary second molar extraction on dentofacial morphology before and after anterior open-bite treatment: a cephalometric study. Odontology. 2009;97:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s10266-008-0093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denison TF, Kokich VG, Shapiro PA. Stability of maxillary surgery in openbite versus non-openbite malocclusions. Angle Orthod. 1989;59:5–10. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1989)059<0005:SOMSIO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altman JI, Oeltjen JC. Nasal deformities associated with maxillary surgery: analysis, prevention, and correction. J Craniofacial Surg. 2007;18:734–739. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3180684328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontes AM, Joondeph DR, Bloomquist DS, Greenlee GM, Wallen TR, Huang GJ. Long-term stability of anterior open-bite closure with bilateral sagittal split osteotomy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frost DE, Fonseca RJ, Turvey TA, Hall DJ. Cephalometric diagnosis and surgical-orthodontic correction of apertognathia. Am J Orthod. 1980;78:657–659. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(80)90205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz-Escalante MA, Aliaga-Del Castillo A, Soldevilla L, Janson G, Yatabe M, Ricardo Voss Zuazola. Extreme skeletal open bite correction with vertical elastics. Angle Orthod. 2017;87:911–923. doi: 10.2319/042817-287.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freitas BV, Abas Frazão MC, Dias L, Fernandes Dos Santos PC, Freitas HV, Bosio JA. Nonsurgical correction of a severe anterior open bite with mandibular molar intrusion using mini-implants and the multiloop edgewise archwire technique. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;153:577–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, et al. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States National Dental Pactice-Based Research Network. J Dent. 2013;41:1051–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandes TM, Sathler R, Natalício GL, Henriques JF, Pinzan A. Comparison of mesiodistal tooth widths in Caucasian, African and Japanese individuals with Brazilian ancestry and normal occlusion. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013;18:130–135. doi: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishara SE, Fernandez Garcia A, Jakobsen JR, Fahl JA. Mesiodistal crown dimensions in Mexico and the United States. Angle Orthod. 1986;56:315–323. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1986)056<0315:MCDIMA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buschang PH, Carrillo R, Ozenbaugh B, Rossouw PE. 2008 survey of AAO members on miniscrew usage. J Clin Orthod. 2008;42:415–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]