Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to elucidate predictive factors for the development of immune-related adverse events (iraes) in patients receiving immunotherapies for the management of advanced solid cancers.

Methods

This retrospective study involved all patients with histologically confirmed metastatic or inoperable melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, or renal cell carcinoma receiving immunotherapy at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario. The type and severity of iraes, as well as potential protective and exacerbating factors, were collected from patient charts.

Results

The study included 78 patients receiving ipilimumab (32%), nivolumab (33%), or pembrolizumab (35%). Melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, and renal cell carcinoma accounted for 70%, 22%, and 8% of the cancers in the study population. In 41 patients (53%) iraes developed, with multiple iraes developing in 12 patients (15%). In most patients (70%), the iraes were of severity grade 1 or 2. Female sex [adjusted odds ratio (oradj): 0.094; 95% confidence interval (ci): 0.021 to 0.415; p = 0.002] and corticosteroid use before immunotherapy (oradj: 0.143; 95% ci: 0.036 to 0.562; p = 0.005) were found to be associated with a protective effect against iraes. In contrast, a history of autoimmune disease (oradj: 9.55; 95% ci: 1.34 to 68.22; p = 0.025), use of ctla-4 inhibitors (oradj: 6.25; 95% ci: 1.61 to 24.25; p = 0.008), and poor kidney function of grade 3 or greater (oradj: 10.66; 95% ci: 2.41 to 47.12; p = 0.025) were associated with a higher risk of developing iraes. A Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test demonstrated that the logistic regression model was effective at predicting the development of iraes (chi-square: 1.596; df = 7; p = 0.979).

Conclusions

Our study highlights several factors that affect the development of iraes in patients receiving immunotherapy. Although future studies are needed to validate the resulting model, findings from the study can help to guide risk stratification, monitoring, and management of iraes in patients given immunotherapy for advanced cancer.

Keywords: Key Words Predictors, immunotherapy, immune-related adverse events, advanced solid cancers

INTRODUCTION

Immunomodulation has recently become an important and promising line of therapy for the treatment of advanced melanoma and an increasing number of other cancer types1. This new line of immunotherapies consists of antibodies that exert their effect by targeting the immune checkpoint inhibitors. Currently available therapy consists of inhibitors of ctla-4, PD-1, and PD-L1. The three most common immunotherapies are ipilimumab (ctla-4 inhibitor), nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor), and pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor).

In a landmark clinical trial by Hodi et al.2, administration of ipilimumab in patients with stage iii or iv melanoma was shown to significantly increase median survival. Similarly, pembrolizumab and nivolumab have both been shown to improve overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with metastatic melanoma3,4. In addition, compared with ipilimumab, the PD-1 inhibitors have demonstrated better efficacy with fewer adverse events, leading to approval by Health Canada for their use in ipilimumab-resistant advanced melanoma in 20145 and in ipilimumab-naïve patients in 2015. The PD-1 inhibitors were subsequently shown to improve survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer6 and renal cell carcinoma7. Since then, immune checkpoint inhibitors have been used in the treatment of various other advanced cancers, including urothelial cancer, head-and-neck carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and small-cell lung cancer.

Despite the clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors, a growing body of evidence has shown that various immune-related adverse events (iraes) occur in a significant portion of patients treated with both anti–ctla-4 and anti–PD-1 antibodies1. Most iraes, including diarrhea and nausea, tend to be mild and self-limiting, but in fewer than 10% of patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, severe (grade 3 or 4), potentially life-threatening iraes can occur8. The iraes can be classified based on the physiologic system affected, the most commonly affected being the endocrine, dermatologic, gastrointestinal, and respiratory systems9. Although iraes can occasionally be managed with a brief course of corticosteroid therapy, grade 3 or 4 iraes typically require termination of immunotherapy and long-term treatment with steroids or other immunosuppressive medications such as infliximab.

With the increasing use of immunotherapy in the management of cancers, determining risk factors for the development of iraes attributable to this group of drugs can provide invaluable help for predicting and better managing patients who develop iraes. Some of the hypothesized risk factors include low muscle attenuation10, history of autoimmune disease9, chronic infections such as hiv and hepatitis11–13, and use of medications with autoimmune side effects14. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have effectively validated those potential risk factors. Several studies have investigated biomarkers that might be predictive of an increased occurrence of iraes, including increased T-cell repertoire15, eosinophil count16, gene expression of CD177 and ceacam117, and blood levels of interleukin 718. Nevertheless, important knowledge gaps remain for the effective identification of patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors who are at risk for developing iraes. In the present retrospective cohort study, we aimed to comprehensively analyze patient factors associated with iraes and to develop a predictive tool for optimal clinical decision-making and patient management.

METHODS

All patients with histologically confirmed metastatic melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, or renal cell carcinoma who were managed at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario (a tertiary care cancer centre) and who received ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, or nivolumab between 1 January 2012 and 18 April 2017 were included in the study. Eligible patients (n = 89) were identified by searching a computerized pharmacy order-entry database. Patients were excluded if they were enrolled in a clinical trial (n = 10). A patient with hepatocellular carcinoma was also excluded because of the small sample size, leaving 78 patients for the study analysis. The study was approved by the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board.

All data were obtained from patient charts. Potential risk factors were categorized into two groups: exacerbating factors and protective factors. A literature review was conducted to support the inclusion of potential risk factors. Exacerbating factors were defined as contributors that might lead to immune dysfunction and a potentially increased risk of iraes. Those factors included a history of autoimmune disease9, history of chronic infection (hiv, hepatitis, shingles)11–13, allergies (medication or environmental)19, previous iraes, high body mass index20, impaired kidney function21,22, or specific medications14 such as antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and statins. Protective factors included medications with immunosuppressive mechanisms14—steroids, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, salicylates, and metformin—that might lead to a lower rate of iraes. All medications identified were in use before the start of immunotherapy.

The iraes were collected as defined in previous studies9,11,12,23. Common side effects identified included skin toxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, and endocrinopathy. Skin toxicity was defined as development of a maculopapular rash or vitiligo. Gastrointestinal toxicity was defined as having watery bowel movements in the absence of an infectious cause or as colitis confirmed by endoscopy. Endocrinopathy included hypophysitis, thyroiditis, adrenal insufficiency, and diabetic ketoacidosis. Because immunotherapy has the potential to affect any organ system, an “other” category was used to collect instances of uncommon iraes. The toxicity severity was graded from 1 to 5 according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.024. The primary outcome was defined as the presence of an irae. Secondary outcomes included multiple iraes (2 or more) and an irae severity of grade 3 or greater.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics software application (version 24.0: IBM, Armonk, NY, U.S.A.) for Windows (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, U.S.A.). Descriptive statistics provide an overview of the characteristics of the study population. Bivariate analyses assessed the relationship between potential predictors and irae incidence rates. Results are reported as odd ratios (ors) and means with 95% confidence intervals (cis). Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. A logistic regression model was then used to determine the association between iraes and the significant predictors identified in the bivariate analyses. To account for the sample size when deriving the model, all variables significant at the alpha level of 0.1 were entered into the multiple logistic regression model—but only if that factor was present in at least 5% of patients with that toxicity event. The backward stepwise elimination method, based on maximum partial likelihood estimates, was used to develop a parsimonious set of predictors while maintaining biologic integrity. The Wald statistic was used to determine the significances of the regression coefficients, with the alpha level set at 0.05. The integrity and predictive accuracy of the model were assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and a receiver operating characteristic curve respectively.

RESULTS

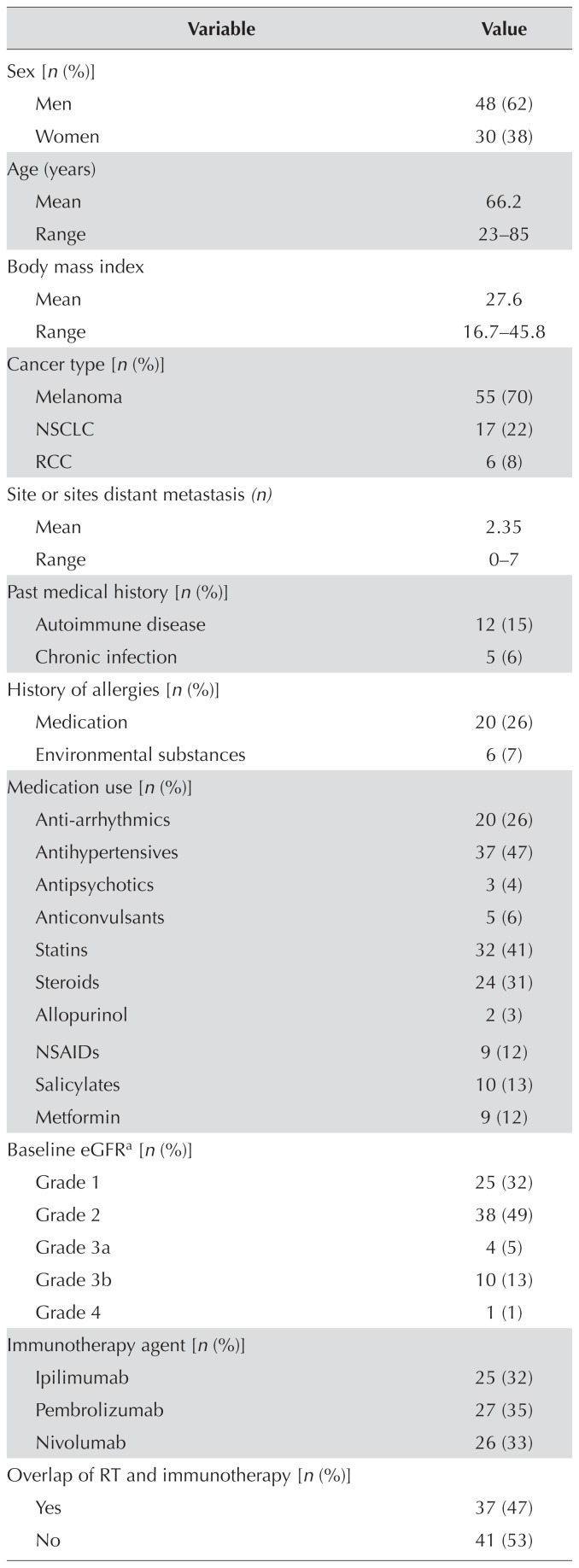

The 78 study patients (30 women, 48 men) had an average age of 66 years (range: 23–85 years). Despite the 23-year-olds (n = 2) being outliers, all patients were included in the analysis given the relevance of a broad age range to a general cancer centre practice. Melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, and renal cell carcinoma accounted for, respectively, 70%, 22%, and 8% of the cancers in the study population. The distribution of nivolumab (33%), pembrolizumab (35%), and ipilimumab (32%) was similar in the study population. Approximately half the patients in the study population (53%) developed an irae, and 15% developed multiple iraes. Most patients (70%) developed an irae of grade 1 or 2. The iraes most commonly involved the skin (22%), gastrointestinal system (17%), and endocrine system (14%). Table i summarizes baseline patient health information, treatment modality, and irae types.

TABLE I.

Demographics and health parameters for the 78 study patients

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex [n (%)] | |

| Men | 48 (62) |

| Women | 30 (38) |

|

| |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean | 66.2 |

| Range | 23–85 |

|

| |

| Body mass index | |

| Mean | 27.6 |

| Range | 16.7–45.8 |

|

| |

| Cancer type [n (%)] | |

| Melanoma | 55 (70) |

| NSCLC | 17 (22) |

| RCC | 6 (8) |

|

| |

| Site or sites distant metastasis (n) | |

| Mean | 2.35 |

| Range | 0–7 |

|

| |

| Past medical history [n (%)] | |

| Autoimmune disease | 12 (15) |

| Chronic infection | 5 (6) |

|

| |

| History of allergies [n(%)] | |

| Medication | 20 (26) |

| Environmental substances | 6 (7) |

|

| |

| Medication use [n (%)] | |

| Anti-arrhythmics | 20 (26) |

| Antihypertensives | 37 (47) |

| Antipsychotics | 3 (4) |

| Anticonvulsants | 5 (6) |

| Statins | 32 (41) |

| Steroids | 24 (31) |

| Allopurinol | 2 (3) |

| NSAIDs | 9 (12) |

| Salicylates | 10 (13) |

| Metformin | 9 (12) |

|

| |

| Baseline eGFRa [n (%)] | |

| Grade 1 | 25 (32) |

| Grade 2 | 38 (49) |

| Grade 3a | 4 (5) |

| Grade 3b | 10 (13) |

| Grade 4 | 1 (1) |

|

| |

| Immunotherapy agent [n (%)] | |

| Ipilimumab | 25 (32) |

| Pembrolizumab | 27 (35) |

| Nivolumab | 26 (33) |

|

| |

| Overlap of RT and immunotherapy [n (%)] | |

| Yes | 37 (47) |

| No | 41 (53) |

|

| |

| Immune-related AEs [n (%)] | |

| Yes, at least 1 | 41 (53) |

| No | 37 (47) |

| Yes, multiple | 12 (15) |

| No, multiple | 66 (85) |

| Yes, ≥grade 3 | 12 (30) |

| No, ≥grade 3 | 28 (70) |

|

| |

| System affected by immune-related AEs [n (%)] | |

| Skin | 17 (22) |

| Gastrointestinal | 13 (17) |

| Endocrine | 11 (14) |

| Otherb | 13 (17) |

As defined by The Renal Association (Bristol, U.K.): grade 1, ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; grade 2, 60–89.9 mL/min/1.73 m2; grade 3a, 45–59.9 mL/min/1.73 m2; grade 3b, 30–44.9 mL/min/1.73 m2; grade 4, 15–29.9 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Respiratory (n=5), renal (n=3), musculoskeletal (n=4), neurologic (n=1).

NSCLC = non-small-cell lung cancer; RCC = renal cell carcinoma; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; eGFR - estimated glomerular filtration rate; RT = radiotherapy; AEs = adverse events.

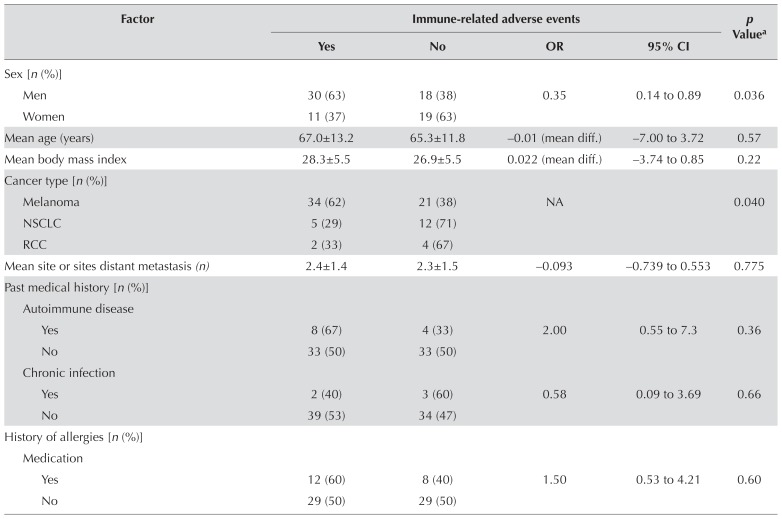

Table ii presents the results of the bivariate analysis of potential predictors and iraes. After adjusting for confounding factors, female sex [adjusted or (oradj): 0.094; 95% ci: 0.021 to 0.415; p = 0.002] and use of corticosteroids before immunotherapy (oradj: 0.143; 95% ci: 0.036 to 0.562; p = 0.005) were found to be associated with a protective effect against the development of iraes. Conversely, a history of autoimmune disease (oradj: 9.55; 95% ci: 1.34 to 68.22; p = 0.025), use of ctla-4 inhibitors (oradj: 6.25; 95% ci: 1.61 to 24.25; p = 0.008), and poor kidney function of grade 3 and greater (oradj: 10.66; 95% ci: 2.41 to 47.12; p = 0.025) were found to be associated with a higher risk of developing iraes. No significant associations between iraes and age, body mass index, number of distant metastatic sites, smoking history, and allergy history were found. Analysis of risk for patients who had already experienced an irae and who were subsequently treated with another immunotherapy was not possible because of the small sample size (n = 11). Table iii presents details.

TABLE II.

Bivariate analyses of risk factors in relation to immune-related adverse events

| Factor | Immune-related adverse events | p Valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Yes | No | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Sex [n (%)] | |||||

| Men | 30 (63) | 18 (38) | 0.35 | 0.14 to 0.89 | 0.036 |

| Women | 11 (37) | 19 (63) | |||

|

| |||||

| Mean age (years) | 67.0±13.2 | 65.3±11.8 | −0.01 (mean diff.) | −7.00 to 3.72 | 0.57 |

|

| |||||

| Mean body mass index | 28.3±5.5 | 26.9±5.5 | 0.022 (mean diff.) | −3.74 to 0.85 | 0.22 |

|

| |||||

| Cancer type [n (%)] | |||||

| Melanoma | 34 (62) | 21 (38) | NA | 0.040 | |

| NSCLC | 5 (29) | 12 (71) | |||

| RCC | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | |||

|

| |||||

| Mean site or sites distant metastasis (n) | 2.4±1.4 | 2.3±1.5 | −0.093 | −0.739 to 0.553 | 0.775 |

|

| |||||

| Past medical history [n (%)] | |||||

| Autoimmune disease | |||||

| Yes | 8 (67) | 4 (33) | 2.00 | 0.55 to 7.3 | 0.36 |

| No | 33 (50) | 33 (50) | |||

| Chronic infection | |||||

| Yes | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 0.58 | 0.09 to 3.69 | 0.66 |

| No | 39 (53) | 34 (47) | |||

|

| |||||

| History of allergies [n(%)] | |||||

| Medication | |||||

| Yes | 12 (60) | 8 (40) | 1.50 | 0.53 to 4.21 | 0.60 |

| No | 29 (50) | 29 (50) | |||

|

| |||||

| History of allergies [n (%)] continued | |||||

| Environmental substances | |||||

| Yes | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 1.89 | 0.33 to 11.0 | 0.68 |

| No | 37 (51) | 35 (49) | |||

|

| |||||

| Medication use [n (%)] | |||||

| Anti-arrhythmics | |||||

| Yes | 13 (65) | 7 (35) | 1.99 | 0.69 to 5.71 | 0.30 |

| No | 28 (48) | 30 (52) | |||

| Antihypertensives | |||||

| Yes | 21 (57) | 16 (43) | 1.38 | 0.56 to 3.37 | 0.51 |

| No | 20 (49) | 21 (51) | |||

| Antipsychotics | |||||

| Yes | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 1.85 | 0.16 to 21.2 | 1.00 |

| No | 39 (52) | 36 (48) | |||

| Anticonvulsants | |||||

| Yes | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 0.58 | 0.09 to 3.69 | 0.66 |

| No | 39 (53) | 34 (47) | |||

| Statins | |||||

| Yes | 22 (69) | 10 (31) | 3.13 | 1.21 to 8.09 | 0.022 |

| No | 19 (41) | 27 (59) | |||

| Steroids | |||||

| Yes | 7 (29) | 17 (71) | 0.24 | 0.09 to 0.69 | 0.007 |

| No | 34 (63) | 20 (37) | |||

| Allopurinol | |||||

| Yes | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | NA | 0.50 | |

| No | 39 (51) | 37 (49) | |||

| NSAIDs | |||||

| Yes | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | 1.15 | 0.28 to 4.63 | 1.00 |

| No | 36 (52) | 33 (48) | |||

| Salicylates | |||||

| Yes | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | 2.33 | 0.56 to 9.79 | 0.32 |

| No | 34 (50) | 34 (50) | |||

| Metformin | |||||

| Yes | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | 1.15 | 0.28 to 4.63 | 1.00 |

| No | 36 (52) | 33 (49) | |||

|

| |||||

| Baseline eGFRb [n (%)] | |||||

| Grades 1–2 | 29 (46) | 34 (54) | 4.70 | 1.21 to 18.2 | 0.022 |

| Grades 3–4 | 12 (80) | 3 (20) | |||

|

| |||||

| Immunotherapy agent [n (%)] | |||||

| Ipilimumab | 17 (68) | 8 (32) | NA | 0.054 | |

| Pembrolizumab | 15 (56) | 12 (44) | |||

| Nivolumab | 9 (35) | 17 (65) | |||

|

| |||||

| Overlap of RT and immunotherapy [n (%)] | |||||

| Yes | 24 (65) | 13 (35) | 2.61 | 1.04 to 6.52 | 0.045 |

| No | 17 (42) | 24 (59) | |||

| Mean days of overlap | 5.0±13.7 | 1.5±2.4 | −3.48 (mean diff.) | −9.61 to 2.66 | 0.26 |

Two-sided.

As defined by The Renal Association (Bristol, U.K.): grade 1, ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; grade 2, 60–89.9 mL/min/1.73 m2; grade 3a, 45–59.9 mL/min/1.73 m2; grade 3b, 30–44.9 mL/min/1.73 m2; grade 4, 15–29.9 mL/min/1.73 m2.

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NSCLC = non-small-cell lung cancer; RCC = renal cell carcinoma; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; eGFR - estimated glomerular filtration rate; RT = radiotherapy.

TABLE III.

Logistical regression analysis of risk factors in relation to immune-related adverse eventsa

| Variable | Comparator | Pts (n) | Immune-related adverse events | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Yes [n (%)] | No [n (%)] | Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis | p Value | |||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||||||

| Sex | Men | 48 | 30 (63) | 18 (38) | 0.35 | 0.14 to 0.89 | 0.094 | 0.021 to 0.415 | 0.002 |

| Women | 30 | 11(37) | 19 (63) | Reference | Reference | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| History of autoimmune disease | No | 66 | 33 (50) | 33 (50) | 2.00 | 0.549 to 7.29 | 9.55 | 1.34 to 68.22 | 0.025 |

| Yes | 12 | 8 (67) | 4(33) | Reference | Reference | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Corticosteroids before immunotherapy | No | 54 | 36 (63) | 20 (37) | 0.242 | 0.086 to 0.685 | 0.143 | 0.036 to 0.562 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 24 | 7 (29) | 17 (71) | Reference | Reference | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Immunotherapy agent | PD-1 | 53 | 24 (45) | 29 (55) | 2.57 | 0.95 to 6.99 | 6.25 | 1.61 to 24.25 | 0.008 |

| Anti–CTLA-4 | 25 | 17 (68) | 8 (32) | Reference | Reference | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Kidney function | Stages 1–2 | 63 | 29 (47) | 34 (54) | 4.69 | 1.21 to 18.25 | 10.66 | 2.41 to 47.12 | 0.025 |

| Stages 3–4 | 15 | 12 (80) | 3 (20) | Reference | Reference | ||||

Hosmer–Lemeshow test for goodness of fit: 0.979.

Pts = patients; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

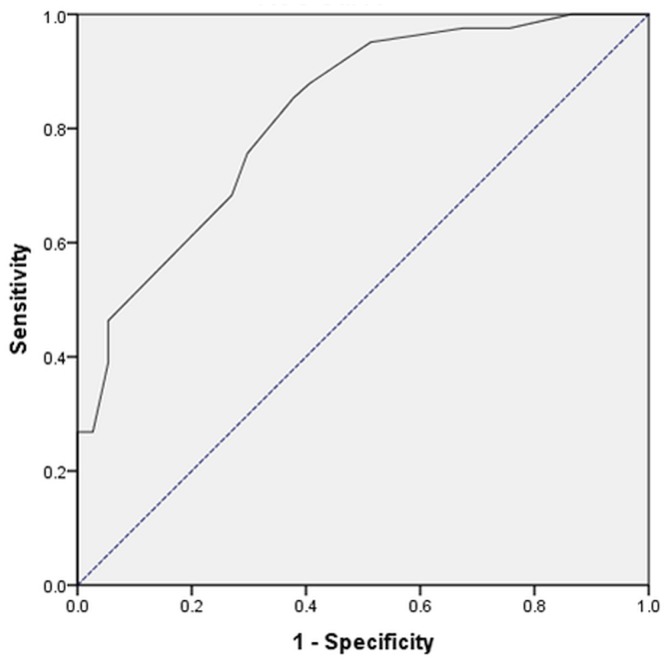

Patients who used statin medications, who had radiation therapy during immunotherapy, or who had melanoma showed an increased risk for iraes on bivariate analysis. However, in the subsequent logistic regression modelling, those factors were not found to be independent predictors. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test showed that, overall, the model was excellent at predicting which patient would or would not develop an irae (chi-square: 1.596; df = 7; p = 0.979). The model was shown to have good predictive accuracy as assessed by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. The area under the curve was 82.4% (95% ci: 73.4% to 91.4%), and it was found to be significantly different relative to the reference line (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the model, demonstrating good prediction accuracy based on the area under the curve (solid line): 82.4% (95% confidence interval: 73.4% to 91.4%), which was significantly different from the reference (dotted line). Diagonal segments are produced by ties.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate factors that predict risk for iraes developing in patients receiving PD-1 and ctla-4 inhibitors. Although iraes were common in our study (more than 50% incidence rate), most patients (70%) developed iraes of mild-to- moderate severity, and only a small proportion (15%) developed multiple iraes. After adjusting for confounding factors, our study suggests that steroid use before immunotherapy, sex, a history of autoimmune disease, immunotherapy with a ctla-4 monoclonal antibody, and abnormal kidney function have statistically significant associations with irae incidence rates.

Corticosteroid use before initiation of immunotherapy (33%, n= 26) was associated with a lower incidence of ir aes. The most common indications for steroid treatment were post-radiation management (54%, n = 14) and symptomatic brain metastases (27%, n = 7). The average dose and duration of corticosteroid before the start of immunotherapy was 35.2 ± 2.49 mg (prednisone equivalent) and 4.9 ± 5.5 weeks respectively. Several previous studies have analyzed the effect of immunosuppressive therapy (indicated for irae management) on immunotherapy efficacy. In a pooled analysis of four clinical trials of nivolumab monotherapy for patients with advanced melanoma, immunosuppressive therapy as indicated for iraes was not associated with differences in the immunotherapy response rate25. Another study also showed no differences in the efficacy of ipilimumab (response rate and overall survival) with immunosuppressive therapy in the context of a nonclinical trial in advanced melanoma patients26. Future studies are required to evaluate the safety and efficacy of steroids given concurrently with immunotherapy, especially in patients who are receiving a significant dose of steroids before they start treatment, because those patients were excluded from clinical trials.

It is well-documented that the innate and adaptive immune systems are more effective in women than in men27, which has been ascribed to the effects of estrogen28–31. Overall, estrogen enhances the immune response through the augmented activation of antigen-presenting cells, thereby resulting in increased antibody-mediated responses to exogenous antigens, increased T-cell cyto-toxicity, and increased cytokine or chemokine levels27–31. We therefore expected women to have a higher incidence of iraes. That expectation was inconsistent with our findings, in that female sex was associated with protection against the development of iraes. Of the 3 most common irae categories in the analysis, skin iraes were associated with male sex (or: 9.51; 95% ci: 1.44 to 62.99; p = 0.012), but gastrointestinal iraes (or: 1.67; 95% ci: 0.31 to 9.05; p = 0.229) and endocrine iraes (or: 1.69; 95% ci: 0.33 to 8.72; p = 1.000) were not found to have significant association with sex. However, those results might be underestimated because of the small sample size.

Currently, few studies have evaluated the safety profiles of immunotherapy agents in patients with underlying autoimmune diseases. In addition, such patients are typically excluded from clinical trials3,6,7,30–36. A recent review article suggested that monotherapy with ctla-4 or PD-1 inhibitors could be safely prescribed to patients with underlying autoimmune diseases, but the evidence for that suggestion was based on retrospective analyses. Our findings, together with the lack of available safety profile data, suggest that a decision to initiate immunotherapy should be evaluated case-by-case and weighed against the potential efficacy of immunotherapy in advanced cancer. If immunotherapy is initiated in patients with an underlying autoimmune disease, vigilant monitoring for the development of iraes would be a crucial component of their care.

Our study suggests that ctla-4 inhibitors are more likely than PD-1 inhibitors to induce iraes. Although that finding is consistent with results from previous studies, the underlying mechanism remains unknown3,6,7,26,32–36. Given the improved efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors, single-agent ctla-4 monoclonal antibodies are rarely used in the clinic, but they have shown some efficacy in patients who have progressed on PD-1 inhibitor therapy37.

Current recommendations suggest that PD-1 and ctla-4 inhibitors should be dosed by weight, and that no dose adjustments are necessary in relation to kidney function. Our study suggests that poor kidney function (stages 3 and 4 per the U.K. Renal Association) is correlated with a higher risk of irae development. Monitoring the incidences of iraes more prudently would therefore be important for patients with poor kidney function at baseline. Future studies evaluating the efficacy of immunotherapy in relation to kidney function would be required to determine whether renal-adjusted doses are appropriate.

Limitations

Several limitations to this study have to be addressed. First, retrospective analysis, by its nature, provides an inferior level of evidence compared with the evidence emerging from prospective studies and might be subject to confounding factors. Nonetheless, our methods minimize confounding by using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and a receiver operating characteristic curve to adjust for confounding factors and to assess the integrity and predictive accuracy of our model.

Second, our study population consisted primarily of patients treated for melanoma, which might limit the generalizability of the findings to other cancer subtypes. Our findings are, however, representative of the general cohort of patients presenting for treatment at our academic centre. Furthermore, the understanding of cancer management is shifting toward molecular and immune checkpoint targets. We therefore believe that, compared with cancer type, cancer immunogenicity or molecular targets will play a more important role in the effects of various treatment modalities.

Lastly, our study was small in sample size. That size limitation was evident in the large confidence intervals accompanying our results. However, the study was adequately powered to detect significant differences, given the high frequency of the outcome of interest. In addition, our analysis considered PD-1 inhibitors and ctla-4 inhibitors alike. We are aware of the varying frequency profiles of iraes for the different immunotherapies. Because of the small sample size, it was not feasible to conduct subgroup analyses of PD-1 inhibitors (n= 53) or ctla-4 inhibitors (n= 25) alone. Nonetheless, our study was able to confirm the higher irae incidence rates for ctla-4 inhibitors compared with PD-1 inhibitors, further suggesting that our study was adequately powered despite the small sample size.

Ultimately, our study was meant to be hypothesis- generating, and we hope that future studies involving multi-cancer centres might validate our hypothesis-generating study.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study provides several valuable insights into an understudied topic in immunotherapy. We have highlighted several factors that can effectively predict the development of iraes in patients receiving immunotherapy. It is of utmost importance to highlight that, of the 5 predictive factors, poor kidney function is correlated with a higher risk of irae development, especially in view of the current guideline-recommended weight-based dosing, with no adjustment based on kidney function required. Further studies to validate the utility of our model are required.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson RAM, Evans TRJ, Fraser AR, Nibbs RJB. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: new strategies to checkmate cancer. Clin Exp Immunol. 2018;191:133–48. doi: 10.1111/cei.13081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1345–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. on behalf of the keynote-006 investigators. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. on behalf of the CheckMate 025 investigators. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villadolid J, Amin A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560–75. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Champiat S, Lambotte O, Barreau E, et al. Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:559–74. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly LE, Power DG, O’Reilly Á, et al. The impact of body composition parameters on ipilimumab toxicity and survival in patients with metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2017;116:310–17. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma A, Thompson JA, Repaka A, Mehnert JM. Ipilimumab administration in patients with advanced melanoma and hepatitis B and C. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e370–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minter S, Willner I, Shirai K. Ipilimumab-induced hepatitis C viral suppression. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e307–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shelburne SA, 3rd, Hamill RJ, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: emergence of a unique syndrome during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:213–27. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao X, Chang C. Diagnosis and classification of drug-induced autoimmunity (dia) J Autoimmunity. 2014;48–49:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh DY, Cham J, Zhang L, et al. Immune toxicities elicted by ctla-4 blockade in cancer patients are associated with early diversification of the T-cell repertoire. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1322–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schindler K, Harmankaya K, Kuk D, et al. Correlation of absolute and relative eosinophil counts with immune-related adverse events in melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab [abstract 9096] J Clin Oncol. 2014;32 [Available online at: http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.9096; cited 25 August 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahabi V, Berman D, Chasalow SD, et al. Gene expression profiling of whole blood in ipilimumab-treated patients for identification of potential biomarkers of immune-related gastrointestinal adverse events. J Transl Med. 2013;11:75. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callahan MK, Yang A, Tandon S, et al. Evaluation of serum il-17 levels during ipilimumab therapy: correlation with colitis [abstract 2505] J Clin Oncol. 2011;29 doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.2505. [Available online at: http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.2505; cited 30 July 2018] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber JS, Yang JC, Atkins MB, Disis ML. Toxicities of immunotherapy for the practitioner. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2092–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ilavská S, Horváthová M, Szabová M, et al. Association between the human immune response and body mass index. Human Immunol. 2012;73:480–5. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thajudeen B, Madhrira M, Bracamonte E, Cranmer LD. Ipilimumab granulomatous interstitial nephritis. Am J Ther. 2015;22:e84–7. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182a32ddc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fadel F, El Karoui K, Knebelmann B. Anti-ctla4 antibody–induced lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:211–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0904283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al. on behalf of the esmo Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: esmo clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):lv119–42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (nci) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Ver 4.0. Bethesda, MD: NCI; 2010. [Available online at: https://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf; cited 25 August 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber JS, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, et al. Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:785–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang TO, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3193–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorak MT, Karpuzoglu E. Gender differences in cancer susceptibility: an inadequately addressed issue. Front Genet. 2012;3:268. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pennell LM, Galligan CL, Fish EN. Sex affects immunity. J Autoimmun. 2012;38:J282–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein SL, Hodgson A, Robinson DP. Mechanisms of sex disparities in inf luenza pathogenesis. J Keukoc Biol. 2012;92:67–73. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0811427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghazeeri G, Abdullah L, Abbas O. Immunological differences in women compared with men: overview and contributing factors. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:163–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karpuzoglu E, Zouali M. The multi-faceted influences of estrogen on lymphocytes towards novel immune-interventions strategies for autoimmunity management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011;40:16–26. doi: 10.1007/s12016-009-8188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daud AI, Wolchok JD, Robert C, et al. Programmed death–ligand 1 expression and response to the anti–programmed death 1 antibody pembrolizumab in melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4102–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horn L, Spigel DR, Vokes EE, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: two-year outcomes from two randomized, open-label, phase iii trials (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057) J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3924–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cella D, Grünwald V, Nathan P, et al. Quality of life in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma given nivolumab versus everolimus in CheckMate 025: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30125-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Escudier B, Sharma P, McDermott DF, et al. on behalf of the CheckMate 025 investigators. CheckMate 025 randomized phase 3 study: outcomes by key baseline factors and prior therapy for nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2017;72:962–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmer L, Apuri S, Eroglu X, et al. Ipilimumab alone or in combination with nivolumab after progression on anti–PD-1 therapy in advanced melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2017;75:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]