Abstract

Studies of visit-to-visit office blood pressure variability (OBPV) as a predictor of cardiovascular events and death in high-risk patients treated to lower BP targets are lacking. We conducted a post hoc analysis of the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), a well-characterized cohort of participants randomized to intensive (<120 mm Hg) or standard (<140 mm Hg) systolic BP targets. We defined OBPV as the coefficient of variation of the systolic BP, using measurements taken during the 3-,6-, 9- and 12-month study visits. In our cohort of 7879 participants, older age, female sex, black race, current smoking, chronic kidney disease and coronary disease were independent determinants of higher OBPV. Use of thiazide-type diuretics or dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers was associated with lower OBPV, while angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker use was associated with higher OBPV. There was no difference in OBPV in participants randomized to standard or intensive treatment groups. We found that OBPV had no significant associations with the composite endpoint of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events (N=324 primary endpoints; adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.85–1.69, highest versus lowest quintile), nor with heart failure or stroke. The highest quintile of OBPV (versus lowest) was associated with all-cause mortality (adjusted HR 1.92, CI 1.22–3.03), although the association of OBPV overall with all-cause mortality was marginal (p=0.07). Our results suggest that clinicians should continue to focus on office BP control rather than on OBPV unless definitive benefits of reducing OBPV are shown in prospective trials.

Keywords: Blood pressure variability, mortality, cardiovascular morbidity, kidney disease, office blood pressure

SUMMARY

In this post hoc analysis of SPRINT, we found no significant association of OBPV with cardiovascular outcomes. The association of OBPV with all-cause mortality was sensitive to the other variables included in the models and to the particular study visits used to define OBPV

Definitive benefits of reducing OBPV from prospective randomized trials are needed before OBPV can become a target of therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic blood pressure (BP) is a dynamic measure, influenced by multiple factors, and it can vary spontaneously from beat to beat, minute to minute, day to day and from visit to visit. The magnitude of this variability can be influenced by factors affecting regional and systemic circulations including arterial stiffness, sympathetic tone, release of vasoactive substances, and baroreceptor sensitivity1, 2. Visit-to-visit office blood pressure variability (OBPV) can also be affected by medication non-adherence, class of antihypertensive medication, timing of medication administration, intensity of BP treatment and patient age3–5.

An initial report by Rothwell and colleagues6 suggested that OBPV was a strong risk factor for stroke, independent of average BP. Since then several other studies seem to have confirmed OBPV as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events, stroke, myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality7–11.However, other studies have failed to show an association of OBPV with clinical outcomes12, 13, particularly in patients at low or intermediate cardiovascular risk14. Other prior studies were performed in highly selected populations, targeted higher levels of BP and some failed to adjust for important comorbidities. Data from high risk patients with hypertension treated to lower BP targets are lacking.

We conducted a post hoc analysis of the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), a well-characterized, contemporary trial that enrolled patients with hypertension, aged >50 years at higher than average cardiovascular risk, and randomized patients 1:1 to intensive (<120 mm Hg) versus standard (<140 mm Hg) systolic BP targets15, 16.We hypothesized that higher OBPV during the study follow-up would be associated with higher risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

METHODS

Study Participants

SPRINT was a multicenter randomized outcome trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health comparing two strategies for control of systolic BP and effects on cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and kidney outcomes15, 16. Briefly, between November 2010 and March 2013, participants with treated or untreated SBP 130–180 mm Hg and age >75 years, or age ≥50 years with at least one of the following indicator of cardiovascular risk were enrolled: evidence of clinical or subclinical cardiovascular disease, 10-year Framingham risk score for cardiovascular disease events ≥15%, or chronic kidney disease (CKD), defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 20 to 59 mL/min per 1.73m2 using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation17. Participants with a history of stroke, diabetes mellitus, polycystic kidney disease, dementia, heart failure, non-adherence to medication, eGFR <20 mL/min per 1.73m2 or ≥1 gram of proteinuria/day (or the equivalent) were not eligible for participation. Participants were randomly assigned to a standard systolic office BP target (<140 mm Hg) or to an intensive systolic BP target (<120 mm Hg).

All participants provided written informed consent for participation in the trial. The trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01206062).

Covariates

Trained study personnel ascertained information about participant baseline sociodemographic data, comorbid conditions and antihypertensive medications during the screening or randomization visit. Fasting blood and urine samples were collected at that time. All assays were performed in a single central laboratory. Serum and urine creatinine were measured using an enzymatic procedure and an auto-analyzer. Urine albumin was measured using an immunoturbidometric method on an auto-analyzer.

Outcomes

The primary composite outcome in SPRINT and in the current analysis was the first occurrence of a myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome not resulting in myocardial infarction, stroke, acute decompensated heart failure, or death from cardiovascular causes. We also examined all-cause mortality, a pre-specified secondary outcome.We examined hospitalized heart failure and stroke as separate outcomes given reported association of OBPV with these outcomes in prior studies6, 7. Outcomes were adjudicated by a committee blinded to the treatment group assignments.

Assessment of Visit-to-Visit Variability of Office Blood Pressure

The BP was measured in the clinic three times in the seated position after the participant had rested quietly for 5 minutes in a chair with back support, legs uncrossed, with 1 minute between readings using a validated automated (oscillometric) BP monitor, Omron 907XL (Omron Healthcare, Lake Forest, IL). The device was initiated by an observer to take three sequential BP measurements separated by one minute. The three measurements were averaged, and this value was recorded as the study visit BP18.

Since SPRINT focused on systolic BP control, our analyses of OBPV also focused on systolic BP. For the current analysis, we used office BP measurements from the 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month study visits only. We excluded 998 participants who were missing any one of these four BP measurements. We chose to use these BP measurements, in order to avoid changes in BP due to medication titration as much as possible. Most participants in the intensive treatment group required successive changes in their medical regimen until the 3-month visit16, in order to reach target systolic BP. After the 3-month visit, average SBP remained relatively stable in both groups. In a sensitivity analysis, we also considered two alternative methods to calculate OBPV: 1) based on five BP measurements taken at randomization, 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month study visits; and 2) based on six BP measurements taken at the 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15- and 18-month study visits.

We excluded 151 participants from the analyses who experienced the primary outcome prior to the 12-month study visit, as this was the observation period during which we ascertained OBPV. We excluded 1 participant who developed end-stage renal disease prior to the 12-month study visit, and 332 participants without any follow-up after the 12-month study visit.

We defined OBPV as the coefficient of variation (standard deviation of mean systolic BP divided by mean systolic BP). We then categorized the cohort by quintiles of OBPV, with Q1 designated as the lowest quintile and Q5 the highest quintile.

Statistical Analysis

We performed multivariable linear regression analysis to identify independent correlates of OBPV and considered all variables listed in Table 1. We calculated rates (per 1000 person-years) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the primary composite outcome, for heart failure, for stroke, and for death from any cause by quintile of OBPV.To examine the association among quintiles of OBPV and clinical outcomes and to avoid assumptions of linearity, we conducted proportional hazard regression with the lowest quintile as the referent (i.e. Q1) and present results as an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used the Wald test to determine whether OBPV overall had a significant association with the specified outcomes. We employed two models: a model with adjustments for age, sex, race (Black versus non-Black), and randomized group, and a full model, which additionally included baseline CKD status, baseline history of coronary artery disease, current smoking status, mean systolic BP and the number of antihypertensive medication classes received at the 3-month study visit. These variables were selected a priori for inclusion in the regression models. We did not include all the variables in Table 1 due to concerns about collinearity of the variables and possible overfitting of the models due to relatively few endpoints.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of the 7888 participants included from the SPRINT cohort, by quintiles of office blood pressure variability. All values are % except where indicated

| Variable | Q1 N=1576 |

Q2 N=1575 |

Q3 N=1577 |

Q4 N=1576 |

Q5 N=1575 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Coefficient of Variation, mean (SD) |

2.7 (1.0) | 5.1 (0.6) | 7.1 (0.6) | 9.5 (0.8) | 14.5 (3.4) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 66.8 (9.1) | 67.1 (9.1) | 67.6 (9.3) | 68.4 (9.3) | 69.6 (9.6) |

| Female sex | 30.8 | 30.2 | 34.1 | 37.2 | 42.0 |

| Black race | 29.3 | 30.0 | 31.5 | 29.3 | 31.9 |

| Uninsured | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 9.2 |

| < High school education | 6.7 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 11.2 |

| No usual healthcare | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| Comorbid conditions | |||||

| Coronary artery disease | 10.3 | 10.7 | 13.3 | 12.9 | 15.9 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6.3 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 9.7 |

| Heart failure | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 4.7 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 7.2 |

| Current smoker | 11.4 | 11.5 | 12.4 | 12.5 | 14.1 |

|

Non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drug use |

14.0 | 13.4 | 15.9 | 15.4 | 15.9 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 22.2 | 25.8 | 26.4 | 29.7 | 34.8 |

| Albuminuria | 15.7 | 18.4 | 17.1 | 20.1 | 22.7 |

|

Body mass index kg/m2, mean (SD) |

30.0 (5.5) | 29.9 (5.6) | 30.0 (5.7) | 29.8 (5.7) | 29.7 (6.2) |

|

Baseline systolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) |

138.2 (14.1) | 139.0 (15.1) | 139.4 (15.0) | 140.7 (15.7) | 140.7 (17.1) |

|

Baseline diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) |

78.2 (11.3) | 78.4 (11.7) | 78.3 (11.7) | 78.3 (11.9) | 77.3 (12.7) |

|

Randomized to standard group |

50.4 | 48.4 | 51.0 | 51.6 | 48.3 |

|

Number of antihypertensive medication classes, mean (SD) |

2.1 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.1) |

|

< Perfect medication adherence |

7.2 | 8.4 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 10.8 |

|

Antihypertensive Medication

Class |

|||||

| Thiazide-type diuretic | 54.8 | 52.6 | 50.1 | 53.0 | 49.1 |

|

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker |

64.6 | 66.6 | 69.7 | 70.0 | 74.7 |

| Beta-blocker | 30.3 | 32.5 | 34.6 | 35.6 | 40.4 |

|

Dihydropyridine calcium channel

blocker |

39.7 | 41.4 | 41.2 | 40.4 | 36.3 |

We were interested in two potential effect modifiers of OBPV and outcomes: randomized treatment group and baseline CKD status. We therefore stratified the crude event rates by these subgroups and included a multiplicative interaction term in the respective models to test for significant interaction.

Given that only 0.47% (N=37) of participants had missing data, we conducted complete case analysis. We defined statistical significance based on two-sided p-values <0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the original 9361 participants enrolled in SPRINT, the current analysis includes 7879 participants (84%) who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The mean OBPV ranged from 2.7% in the lowest quintile (Q1) to 14.5% in the highest quintile (Q5; Table 1). The mean systolic BP was 128 mm Hg and mean diastolic BP was 72 mm Hg for the overall cohort during the period of OBPV ascertainment.

Correlates of OBPV

Participants in higher quintiles of OBPV were generally at higher cardiovascular risk: older, more often female and of Black race, and had a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, CKD and albuminuria (Table 1). Participants in higher quintiles of OBPV required more medications to achieve the target BP and were more likely to report use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), beta-blockers and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and less likely to report the use of thiazide-type diuretics or dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers at the 3-month study visit (Table 1).

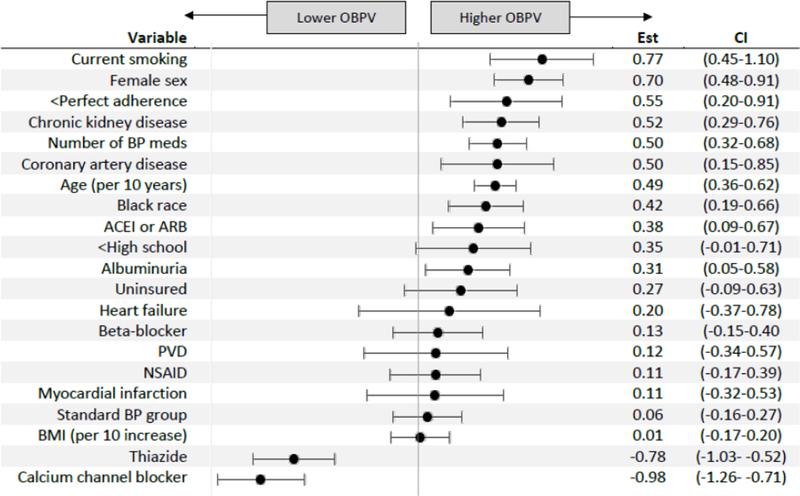

In multivariable-adjusted regression models, we found that current smoking, female sex, older age and Black race were associated with higher OBPV (Figure 1). Baseline CKD and coronary artery disease were associated with higher OBPV; history of heart failure, peripheral vascular disease or myocardial infarction were not associated with OBPV. Prescription of more antihypertensive medication classes and reporting less than perfect adherence were associated with higher OBPV, while randomization group was not. Finally, in terms of antihypertensive medication classes, reported use of thiazide-type diuretics or dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers remained significantly associated with lower OBPV, while reported use of ACEI or ARB remained significantly associated with higher OBPV; the reported use of beta-blockers was not associated with OBPV (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Determinants of visit-to-visit office blood pressure variability (OBPV) from multivariable-adjusted linear regression models. Abbreviations: ACEI = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; PVD = peripheral vascular disease; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; BMI = body mass index

Association of VVV of BP with Endpoints

Primary composite endpoint

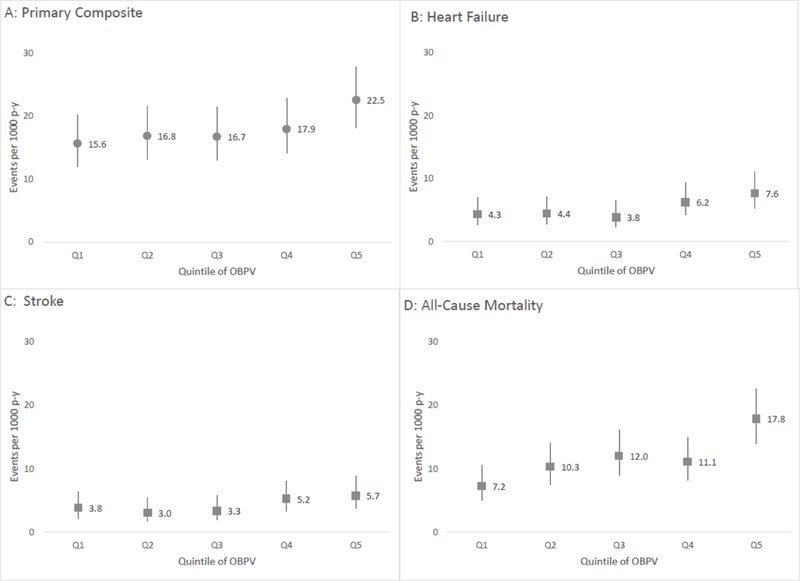

A total of 324 participants experienced the primary composite endpoint during an average of 2.3 years (18,122 patient-years) of follow-up starting from the 12-month visit (Table 2). The crude event rate for the primary composite endpoint was 15.6/ 1000 patient-years for participants in the highest quintile of OBPV (Q5), compared to a crude event rate of 10.9 / 1000 patient years for participants in Q1 (Figure 2A). However, in demographic- and fully-adjusted models, OBPV was not significantly associated with the primary composite endpoint (p=0.23; Table 3). Results were not materially changed in sensitivity analyses that calculated OBPV using BP measured at randomization, 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month study visits or using BP measured at the 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, 15-, and 18-month study visits (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 2:

Number of participants overall and by randomized treatment group and number of specified outcomes by quintile of office based blood pressure variability

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Participants | Events | Participants | Events | Participants | Events | Participants | Events | Participants | Events |

|

Primary

Composite |

||||||||||

| All | 1576 | 57 | 1575 | 61 | 1577 | 60 | 1576 | 65 | 1575 | 81 |

| Standard | 795 | 36 | 762 | 37 | 805 | 34 | 814 | 39 | 760 | 45 |

| Intensive | 781 | 21 | 813 | 24 | 772 | 26 | 762 | 26 | 815 | 36 |

| Heart Failure | ||||||||||

| All | 1576 | 16 | 1575 | 16 | 1577 | 14 | 1576 | 23 | 1575 | 28 |

| Standard | 795 | 9 | 762 | 6 | 805 | 12 | 814 | 16 | 760 | 17 |

| Intensive | 781 | 7 | 813 | 10 | 772 | 2 | 762 | 7 | 815 | 11 |

| Stroke | ||||||||||

| All | 1576 | 14 | 1575 | 11 | 1577 | 12 | 1576 | 19 | 1575 | 21 |

| Standard | 795 | 11 | 762 | 5 | 805 | 6 | 814 | 11 | 760 | 8 |

| Intensive | 781 | 3 | 813 | 6 | 772 | 6 | 762 | 8 | 815 | 13 |

|

All-Cause

Mortality |

||||||||||

| All | 1576 | 27 | 1575 | 38 | 1577 | 44 | 1576 | 41 | 1575 | 66 |

| Standard | 795 | 17 | 762 | 25 | 805 | 27 | 814 | 22 | 760 | 38 |

| Intensive | 781 | 10 | 813 | 13 | 772 | 17 | 762 | 19 | 815 | 28 |

Figure 2:

Event rates per 1000 patient-years of A) the primary composite endpoint; B) heart failure; C) stroke; and D) all-cause mortality by quintile of visit-to-visit office blood pressure variability (OBPV).

Table 3:

Association of quintile of visit-to-visit office blood pressure variability with the specified outcomes

| Demographic-adjusted* | Full Model† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| Primary composite cardiovascular | ||||||

| Q1 | ref | - | 0.43 | ref | - | 0.92 |

| Q2 | 1.08 | 0.75–1.54 | 1.04 | 0.73–1.50 | ||

| Q3 | 1.03 | 0.72–1.48 | 0.97 | 0.67–1.39 | ||

| Q4 | 1.09 | 0.76–1.55 | 1.02 | 0.71–1.45 | ||

| Q5 | 1.34 | 0.95–1.88 | 1.13 | 0.80–1.60 | ||

| Heart Failure | ||||||

| Q1 | ref | - | ref | - | ||

| Q2 | 1.01 | 0.51–2.02 | 0.96 | 0.48–1.91 | ||

| Q3 | 0.81 | 0.39–1.66 | 0.39 | 0.74 | 0.36–1.52 | 0.66 |

| Q4 | 1.28 | 0.67–2.42 | 1.16 | 0.61–2.21 | ||

| Q5 | 1.46 | 0.79–2.71 | 1.17 | 0.63–2.20 | ||

| Stroke | ||||||

| Q1 | ref | - | ref | - | ||

| Q2 | 0.78 | 0.36–1.72 | 0.76 | 0.34–1.67 | ||

| Q3 | 0.83 | 0.38–1.79 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.36–1.68 | 0.68 |

| Q4 | 1.25 | 0.62–2.49 | 1.16 | 0.58–2.32 | ||

| Q5 | 1.32 | 0.67–2.60 | 1.13 | 0.57–2.26 | ||

| All-cause mortality | ||||||

| Q1 | ref | - | 0.007 | ref | - | 0.07 |

| Q2 | 1.42 | 0.87–2.33 | 1.38 | 0.85–2.27 | ||

| Q3 | 1.59 | 0.99–2.57 | 1.52 | 0.94–2.46 | ||

| Q4 | 1.43 | 0.88–2.33 | 1.36 | 0.84–2.22 | ||

| Q5 | 2.23 | 1.42–3.50 | 1.92 | 1.22–3.03 | ||

adjusted for age, sex, race, randomized treatment group

adjusted for age, sex, race, CKD, coronary artery disease, number of antihypertensive agents, mean systolic blood pressure and randomized treatment group

Participants randomized to the standard treatment group had a higher incidence of the primary composite endpoint compared with participants randomized to standard treatment (Table 2, Supplemental Figure S1A&B). However, we found no evidence that randomized treatment group modified the association of OBPV with the primary composite endpoint (pinteraction =1.0).

Heart Failure and Stroke Hospitalizations

There were 97 heart failure hospitalizations and 77 stroke hospitalizations during the follow-up period (Table 2, Figure 2A). For both endpoints, the crude event rates were slightly higher in the highest quintile (Q5) of OBPV compared with the lowest quintile (Q1, Figure 2B&C). However, in adjusted models we found no significant association of OBPV with heart failure or with stroke hospitalizations (Table 3, Supplemental Figure S1C-F), and no evidence that the associations were modified by randomized treatment group (pinteraction =0.09 and 0.4, for heart failure and stroke, respectively).Results were not materially changed in sensitivity analyses using alternative study visits to calculate OBPV (Supplemental Table S1).

All-cause mortality

We observed higher crude rates of all-cause mortality in the highest quintile of OBPV compared with the lowest quintile: 12.5 versus 5.1 / 1000 patient years (Table 2, Figure 2D). In demographic-adjusted models, OBPV was significantly associated with all-cause mortality (Q5 versus Q1 HR=2.23, CI 1.42–3.50; overall p=0.007), but the association was attenuated in fully adjusted models (HR = 1.92, CI 1.22–3.03, overall p=0.07, Table 3). While the results were not materially changed when using OBPV calculated from randomization through the 12-month study visit, the analysis calculating OBPV using BP from the 3-month through 18-month study visits did show a significant association of OBPV with all-cause mortality (p=0.01, Supplemental Table S1).

Participants randomized to the standard treatment group had a higher crude rate of all-cause mortality than patients randomized to the intensive group (Supplemental Figure S1G&H) but we did not observe any interaction of randomized treatment group on this association (pinteraction =0.9).

Chronic Kidney Disease Subgroup Analyses

Participants with baseline CKD generally experienced more heart failure and stroke hospitalizations, and more deaths compared to participants without baseline CKD (Supplemental Table S2, Supplemental Figure S2). In multivariable adjusted models, CKD was associated with significantly higher risks of the primary composite endpoint and heart failure (Supplemental Table S3). However, there was no evidence that baseline CKD status significantly modified the association of OBPV and any of the four endpoints (pinteraction > 0.4 for all endpoints).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of SPRINT, we found that OBPV was not significantly associated with the primary composite endpoint of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events, or with heart failure or stroke hospitalizations. Results were consistent between our primary analysis (which calculated OBPV from the four BP measurements taken from the 3-month through 12-month study visit), and sensitivity analyses using OBPV calculated from randomization through the 12-month visit, and from the 3-month through the 18-month visit In our primary analysis, we found that the highest quintile of OBPV (versus the lowest quintile) was associated with all-cause mortality, but the association was attenuated and no longer significant after adjusting for other factors. In sensitivity analyses using alternative methods of calculating OBPV, the association of OBPV with all-cause mortality was strengthened.

Our results contrast with other studies using data from randomized clinical trials that showed a significant association of OBPV with cardiovascular events. For example, Rothwell and colleagues examined data from the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA), which randomized patients with hypertension and three or more additional cardiovascular risk factors (but no coronary artery disease) to either an amlodipine-based or atenolol-based regimen; target clinic BP was set at <140/90 mm Hg, or <130/80 in patients with diabetes mellitus6. These authors found that the highest decile of OBPV (defined by coefficient of variation) had a 2.06-fold (CI 1.28–3.31) higher unadjusted risk of stroke and 1.57-fold (CI 1.14–2.16) higher risk of coronary events, compared with the lowest decile. There has also been a post hoc analysis on OBPV and outcomes using data from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), which randomly assigned patients with hypertension and ≥1 additional cardiovascular risk factor to receive amlodipine, lisinopril, or chlorthalidone, targeting a BP <140/90 mm Hg 7.In ALLHAT, the highest quintile of OBPV (defined as the SD of systolic BP) was associated with a 1.30-fold (CI 1.06–1.59) higher risk of fatal or nonfatal coronary heart disease, again, in contrast to our findings.

One reason for why our findings differed from ASCOT-BPLA and ALLHAT could stem from the lower achieved systolic BP in SPRINT (128 mm Hg for the overall cohort), which may have led to lower OBPV in our cohort (7.8%). For example, in Rothwell’s reanalysis of different trials6, the mean achieved systolic BP was approximately 145 mm Hg, and the OBPV across the four trials included (defined as coefficient of variation) ranged from 8.2 to 10.0, higher than the mean OBPV in our analysis. Importantly, however, we did not find any evidence that the randomized treatment group modified the (non-significant) association of OBPV with the risk for the primary composite endpoint or heart failure. Moreover, an analysis of the European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis trial 14, which had a higher mean systolic BP (163 mm Hg) but lower median OBPV (5.7%) when compared with SPRINT, also found no significant association of OBPV with cardiovascular outcomes. Thus achieved BP alone does not account for differences among the studies. A recent comprehensive systematic review of over 312 analyses of OBPV with cardiovascular events or death found that 42% showed no significant association11, while 58% did show a significant association. Heterogeneity in terms of patient characteristics, variables included in adjusted models, number of visits used to calculate OBPV (from as few as 38 to 3519 or more), metrics of OBPV used, and modelling of OBPV as a continuous or categorical variable could also contribute to the mixed results20. Clearly, standardized definitions and approaches to OBPV are needed.

We found that SPRINT participants who were older, current smokers, and with coronary artery disease had higher OBPV – clearly higher risk patients, suggesting that OBPV may be a marker of high risk but not necessarily causally related to outcomes. Baseline mild-to-moderate CKD was associated not only with higher OBPV but also with markedly higher crude rates of the primary composite endpoint and death from any cause compared with participants without CKD, consistent with numerous previous studies 21, 22. The contribution of these variables to the risk of death from any cause was evident in our analysis, as the association of OBPV with all-cause mortality was significant, but attenuated in fully adjusted models that included CKD (HR 1.92, CI 1.22–3.03, Q5 vs. Q1). Our results are consistent with the findings from ALLHAT, which showed a 1.58-fold (CI 1.32–1.90) higher risk of all-cause mortality for patients in the highest quintile of OBPV compared with the lowest quintile in fully adjusted models7.

Participants with less-than-perfect medication adherence had higher OBPV in our analysis, which is consistent with previous studies5, 10. Also consistent with previously reported results, we found that use of thiazide diuretics or dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers was associated with lower OBPV, while ACEI or ARB use was associated with higher OBPV. Similar findings were observed in ASCOT-BPLA, where participants randomized to the amlodipine-based group had lower OBPV compared to the atenolol-based group23. Interestingly, in ASCOT-BPLA the reduction in OBPV completely accounted for the lower risk of stroke and coronary events found in the amlodipine group as compared with the atenolol group23. In contrast, participants in ALLHAT randomized to receive chlorthalidone and amlodipine had lower OBPV compared with patients randomized to the lisinopril arm, but there was no difference in cardiovascular outcomes24. It is possible that calcium channel blockers and diuretics provide more consistent and reliable BP control, thus lowering OBPV, but the exact mechanism remains uncertain. Moreover, whether lowering OBPV per se can reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular events independently of BP lowering effects has yet to be tested directly in prospective clinical trials.

The strengths of this analysis include, but are not limited to the following: inclusion of a large, diverse hypertensive population at high risk for CV events; measurements of BP that were carefully ascertained to limit over- or underestimation of clinic BP; assessment of OBPV starting from the 3-month visit so as to avoid period when medications were most actively titrated; models adjusted for randomized treatment group, demographics and other comorbidities; and inclusion of information on medication adherence. There are, however, several limitations to this analysis as well. First, OBPV may have differential association with different clinical outcomes (i.e. stroke)6, 25. SPRINT was not powered to examine individual components of the primary endpoint and there were relatively few heart failure and stroke events in SPRINT. Second, we did not have information on medication timing relative to the study visit, which could have affected OBPV measurements. Third, although SPRINT was diverse in terms of age, sex, race, and inclusion of patients with baseline kidney and heart disease, the study excluded patients with diabetes mellitus or history of stroke, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to those important patient populations.

PERSPECTIVES

In summary, in this analysis of SPRINT, we found no significant association of OBPV with cardiovascular outcomes. The association of OBPV with all-cause mortality was sensitive to the other variables included in the models and to the particular study visits used to define OBPV. Our results suggest that clinicians should continue to focus on absolute BP targets rather than on efforts to reduce OBPV until and if definitive benefits of reducing OBPV are shown in prospective randomized trials.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

WHAT IS NEW

This is one of the few studies to examine visit-to-visit office based blood pressure variability (OBPV) in patients at high cardiovascular risk.

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) is unique in that participants were treated to lower blood pressure targets than in previous studies on this topic.

OBPV is not significantly associated with cardiovascular events in this high risk patient population.

WHAT IS RELEVANT

SPRINT participants who were older, current smokers, had coronary artery disease or chronic kidney disease had higher OBPV, suggesting that OBPV is a marker of high risk but not necessarily causally related to poorer outcomes.

Clinicians should continue to focus on office BP control rather than on efforts to reduce OBPV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SOURCES OF FUNDING

TIC is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), 5K23DK095914.

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial is funded with Federal funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the NIDDK, the National Institute on Aging (NIA), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), under Contract Numbers HHSN268200900040C, HHSN268200900046C, HHSN268200900047C, HHSN268200900048C, HHSN268200900049C, and Inter-Agency Agreement Number A-HL-13–002-001. It was also supported in part with resources and use of facilities through the Department of Veterans Affairs. The SPRINT investigators acknowledge the contribution of study medications (azilsartan and azilsartan combined with chlorthalidone) from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. All components of the SPRINT study protocol were designed and implemented by the investigators. The investigative team collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. All aspects of manuscript writing and revision were carried out by the coauthors. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government. For a full list of contributors to SPRINT, please see the supplementary acknowledgement list16.

We also acknowledge the support from the following CTSAs funded by NCATS:

CWRU: UL1TR000439, OSU: UL1RR025755, U Penn: UL1RR024134& UL1TR000003, Boston: UL1RR025771, Stanford: UL1TR000093, Tufts: UL1RR025752, UL1TR000073 & UL1TR001064, University of Illinois: UL1TR000050, University of Pittsburgh: UL1TR000005, UT Southwestern: 9U54TR000017-06, University of Utah: UL1TR000105-05, Vanderbilt University: UL1 TR000445, George Washington University: UL1TR000075, University of CA, Davis: UL1 TR000002, University of Florida: UL1 TR000064, University of Michigan: UL1TR000433, Tulane University: P30GM103337 COBRE Award NIGMS.

WCC has an Institutional grant from Eli Lilly and is an uncompensated consultant for Takeda

VP received grants from Astra-Zeneca, Sanofi, DCRI, VA Co-Op studies and the NIH

GSS received honoraria from Boehringer, Mearini, Novartis, Omron, SanofiAventis, Servier and has research contracts with Bayer and Boehringer.

CT has received research grants or honoraria from Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, Bayer, Novartis, Atra-Zeneca, Boehringer, Pfizer, Sanofi, Vianex and Servier.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURES

Contributor Information

Tara I. Chang, Stanford University School of Medicine, Division of Nephrology

David M. Reboussin, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Glenn M. Chertow, Stanford University School of Medicine, Division of Nephrology

Alfred K. Cheung, Division of Nephrology & Hypertension, University of Utah and Renal Section, Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Health Care System

William C. Cushman, Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center

William J. Kostis, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Division of Cardiovascular Disease and Hypertension

Gianfranco Parati, Dept of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano-Bicocca & St. Luke Hospital, Italian Auxology Institute.

Dominic Raj, Division of Renal Diseases and Hypertension, George Washington University.

Erik Riessen, Intermountain Medical Center.

Brian Shapiro, Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville.

George S Stergiou, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, School of Medicine.

Raymond R. Townsend, University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine

Konstantinos Tsioufis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, School of Medicine.

Paul K. Whelton, Department of EpidemiologyTulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine

Jeffrey Whittle, Primary Care Division, Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center.

Jackson T. Wright, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Case Western Reserve University, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center

Vasilios Papademetriou, Department of Veterans Affairs and Georgetown University For the SPRINT research group.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stergiou GS, Parati G, Vlachopoulos C, et al. Methodology and technology for peripheral and central blood pressure and blood pressure variability measurement: Current status and future directions - position statement of the european society of hypertension working group on blood pressure monitoring and cardiovascular variability. J Hypertens 2016;34:1665–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parati G, Ochoa JE, Lombardi C, Bilo G. Blood pressure variability: Assessment, predictive value, and potential as a therapeutic target. Curr Hypertens Rep 2015;17:537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancia G Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability: An insight into the mechanisms. Hypertension 2016;68:32–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostis JB, Sedjro JE, Cabrera J, Cosgrove NM, Pantazopoulos JS, Kostis WJ, Pressel SL, Davis BR. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability and cardiovascular death in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014;16:34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong K, Muntner P, Kronish I, Shilane D, Chang TI. Medication adherence and visit-to-visit variability of systolic blood pressure in african americans with chronic kidney disease in the aask trial. J Hum Hypertens 2016;30:73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O’Brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet 2010;375:895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muntner P, Whittle J, Lynch AI, Colantonio LD, Simpson LM, Einhorn PT, Levitan EB, Whelton PK, Cushman WC, Louis GT, Davis BR, Oparil S. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and mortality: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muntner P, Shimbo D, Tonelli M, Reynolds K, Arnett DK, Oparil S. The relationship between visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure and all-cause mortality in the general population: Findings from nhanes iii, 1988 to 1994. Hypertension 2011;57:160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimbo D, Newman JD, Aragaki AK, LaMonte MJ, Bavry AA, Allison M, Manson JE, Wassertheil-Smoller S. Association between annual visit-to-visit blood pressure variability and stroke in postmenopausal women: Data from the women’s health initiative. Hypertension 2012;60:625–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kronish IM, Lynch AI, Oparil S, Whittle J, Davis BR, Simpson LM, Krousel-Wood M, Cushman WC, Chang TI, Muntner P. The association between antihypertensive medication nonadherence and visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure: Findings from the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial. Hypertension 2016;68:39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz KM, Tanner RM, Falzon L, Levitan EB, Reynolds K, Shimbo D, Muntner P. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension 2014;64:965–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schutte R, Thijs L, Liu YP, Asayama K, Jin Y, Odili A, Gu YM, Kuznetsova T, Jacobs L, Staessen JA. Within-subject blood pressure level--not variability--predicts fatal and nonfatal outcomes in a general population. Hypertension 2012;60:1138–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hara A, Thijs L, Asayama K, Jacobs L, Wang JG, Staessen JA. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active drugs for effects on risks associated with blood pressure variability in the systolic hypertension in europe trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e103169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancia G, Facchetti R, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability, carotid atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular events in the european lacidipine study on atherosclerosis. Circulation 2012;126:569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambrosius WT, Sink KM, Foy CG, et al. The design and rationale of a multicenter clinical trial comparing two strategies for control of systolic blood pressure: The systolic blood pressure intervention trial (sprint). Clin Trials 2014;11:532–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Group SR, Wright JT, Jr., Williamson JD, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D, Group* ftMoDiRDS. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Annals of Internal Medicine 1999;130:461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sprint manual of operations related to blood pressure measurement technique. https://www.sprinttrial.org/public/dspHome.cfm. Date Accessed: 5/26/2017.

- 19.Brunelli SM, Thadhani RI, Lynch KE, Ankers ED, Joffe MM, Boston R, Chang Y, Feldman HI. Association between long-term blood pressure variability and mortality among incident hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;52:716–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Shi X, Ma C, Zheng H, Xiao J, Bian H, Ma Z, Gong L. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability is a risk factor for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 2017;35:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papademetriou V, Lovato L, Doumas M, Nylen E, Mottl A, Cohen RM, Applegate WB, Puntakee Z, Yale JF, Cushman WC, Group AS. Chronic kidney disease and intensive glycemic control increase cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int 2015;87:649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1296–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O’Brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, Sever PS. Effects of β blockers and calcium-channel blockers on within-individual variability in blood pressure and risk of stroke. The Lancet Neurology 2010;9:469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muntner P, Levitan EB, Lynch AI, Simpson LM, Whittle J, Davis BR, Kostis JB, Whelton PK, Oparil S. Effect of chlorthalidone, amlodipine, and lisinopril on visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure: Results from the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014;16:323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pringle E, Phillips C, Thijs L, Davidson C, Staessen JA, de Leeuw PW, Jaaskivi M, Nachev C, Parati G, O’Brien ET, Tuomilehto J, Webster J, Bulpitt CJ, Fagard RH, Syst-Eur investigators. Systolic blood pressure variability as a risk factor for stroke and cardiovascular mortality in the elderly hypertensive population. J Hypertens 2003;21:2251–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.