Abstract

Linezolid (LZD) has become one of the most important antimicrobial agents for infections caused by gram-positive bacteria, including those caused by Enterococcus species. LZD-resistant (LR) genetic features include mutations in 23S rRNA/ribosomal proteins, a plasmid-borne 23S rRNA methyltransferase gene cfr, and ribosomal protection genes (optrA and poxtA). Recently, a cfr gene variant, cfr(B), was identified in a Tn6218-like transposon (Tn) in a Clostridioides difficile isolate. Here, we isolated an LR Enterococcus faecalis clinical isolate, KUB3006, from a urine specimen of a patient with urinary tract infection during hospitalization in 2017. Comparative and whole-genome analyses were performed to characterize the genetic features and overall antimicrobial resistance genes in E. faecalis isolate KUB3006. Complete genome sequencing of KUB3006 revealed that it carried cfr(B) on a chromosomal Tn6218-like element. Surprisingly, this Tn6218-like element was almost (99%) identical to that of C. difficile Ox3196, which was isolated from a human in the UK in 2012, and to that of Enterococcus faecium 5_Efcm_HA-NL, which was isolated from a human in the Netherlands in 2012. An additional oxazolidinone and phenicol resistance gene, optrA, was also identified on a plasmid. KUB3006 is sequence type (ST) 729, suggesting that it is a minor ST that has not been reported previously and is unlikely to be a high-risk E. faecalis lineage. In summary, LR E. faecalis KUB3006 possesses a notable Tn6218-like-borne cfr(B) and a plasmid-borne optrA. This finding raises further concerns regarding the potential declining effectiveness of LZD treatment in the future.

Keywords: linezolid, Enterococcus, cfr(B), Tn6218, optrA

Introduction

Since gaining regulatory approval in 2000 for clinical use, linezolid (LZD) has become one of the most important antimicrobial agents for infections caused by gram-positive bacteria, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin (VCM)-resistant enterococci (Zahedi Bialvaei et al., 2017). Enterococcus faecalis is a lactic acid-producing gram-positive bacterium that is commonly found in the intestinal tracts of humans and animals and is implicated in several fatal clinical infections, such as bacteremia and infective endocarditis (Dahl and Bruun, 2013; Falcone et al., 2015; Beganovic et al., 2018).

LZD-resistant (LR) isolates generally exhibit alterations in the central loop of domain V in the 23S rRNA in the bacterial ribosome. In enterococci, the G2576T (Escherichia coli numbering) mutation in the 23S rRNA gene(s) has been the predominant cause of the loss of susceptibility to LZD (Kloss et al., 1999), and additional mutations in the L3/L4 ribosomal proteins have also been shown to cause decreased susceptibility to LZD (Mendes et al., 2014).

In addition, a plasmid-borne chloramphenicol-florfenicol resistance gene, cfr, was identified in a Staphylococcus sciuri isolate obtained from the nasal swab of a calf (Schwarz et al., 2000). This plasmid-borne LR gene has been also identified in a human clinical MRSA isolate (Toh et al., 2007). Cfr methyltransferase, which mediates the transfer of methyl residues on adenine 2503 in 23S rRNA (Kehrenberg et al., 2005), can mediate the PhLOPSA phenotype (resistance to phenicols, lincosamides, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A compounds) (Long et al., 2006). The cfr gene has been documented in a variety of bacterial isolates and first emerged in coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) (Witte and Cuny, 2011). LR E. faecalis carrying cfr was first described in an animal isolate in 2011 from China (Liu et al., 2012); subsequently, clinical LR E. faecalis isolate was identified from a patient subjected to prolonged antimicrobial therapy in Thailand in 2010 (Diaz et al., 2012). Further studies have suggested that livestock-associated CNS (He et al., 2014; Schoenfelder et al., 2017), MRSA (Li et al., 2017), and Enterococcus spp. (Torres et al., 2018) have disseminated and harbor a significant resistance gene pool, including cfr, in livestock environments.

The plasmid-mediated LR determinant optrA, encoding the ATP-binding cassette F (ABC-F) family protein, was first characterized and identified in E. faecalis and E. faecium from food-producing animals and from humans in China in 2009 (Wang et al., 2015). ABC-F proteins have been classified into three groups based on their antibiotic resistance: (i) Msr homologs, resistant to macrolides and streptogramin B; (ii) Vga/Lsa/Sal homologs, resistant to lincosamides, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A; and (iii) OptrA homologs, resistant to phenicols and oxazolidinones (Sharkey et al., 2016). Unlike other ABC transporters, these ABC-F proteins lack the transmembrane domain characteristic to transporters and are believed to confer antibiotic resistance via a ribosomal protection mechanism by interacting with the ribosome and displacing the bound drug (Sharkey et al., 2016). A cryo-EM structural analysis demonstrated a universal resistance mechanism in which ABC-F protein binding leads to ribosomal conformational changes, resulting in the release of the antibiotic (Su et al., 2018). Further epidemiological study for optrA dissemination suggested that nationwide surveillance for optrA-positive LR Enterococcus isolates in China showed a marked increase in detection from 0.4 to 3.9% during the 10-year period (2004–2014) (Cui et al., 2016), and the review summarized the optrA-positive LR Enterococcus isolates from animal origins and environment (Torres et al., 2018).

Recently, the newly identified poxtA gene in the MRSA AOUC-0915 strain was found to encode an OptrA homolog. The expression of poxtA in E. coli, S. aureus, and E. faecalis results in a decrease in susceptibility to phenicols, oxazolidinones, and tetracyclines (Antonelli et al., 2018).

Two clinical surveillance programs have monitored LZD susceptibility among clinically significant isolates. The global Zyvox Annual Appraisal of Potency and Spectrum (ZAAPS) program, comprising medical centers in 32 ex-USA countries, reported the continued long-term and stable in vitro potency of LZD against staphylococci and Enterococcus faecium clinical isolates in 2015 (Pfaller et al., 2017b). However, a limited number of isolates exhibited mutations in the 23S rRNA gene and/or L3/L4-encoding proteins, in addition to plasmid-mediated resistance determinants (cfr and optrA), leading to a decreased susceptibility to LZD [A minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ≥8 μg/mL is considered “resistant” by CLSI M100-S28, while a MIC of >4 mg/L is considered “resistant” by EUCAST]. The USA Linezolid Experience and Accurate Determination of Resistance (LEADER) program has reported that the overall LR rate remained a modest 1% in enterococci from 2011 to 2015 (Pfaller et al., 2017a), but clonal dissemination of LR strains has been suggested in staphylococci and E. faecium clinical isolates based on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) profile analysis.

Recently, a cfr gene variant, cfr(B), was identified from Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium or Peptoclostridium) difficile isolates (Marin et al., 2015). Further investigation in the United States under the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program suggested that cfr(B)-positive E. faecium was found among human clinical isolates (Deshpande et al., 2015). An increasing number of LR E. faecium clinical isolates from <1% in 2008 to >9% in 2014 in Germany has caused a concern (Klare et al., 2015). Moreover, cfr(B) from E. faecium isolates in Germany was acquired in a plasmid-mediated manner, following cfr(B) plasmid integration on the chromosome in some isolates (Bender et al., 2016). In contrast to the plasmid-borne cfr and cfr(B) genes, the cfr(B) gene was observed to be chromosomally located and embedded in a Tn6218-like transposon (Tn) in the C. difficile strains Ox2167 and Ox3196 (Deshpande et al., 2015).

Various mobile genetic elements (MGE) have been shown to contribute to the acquisition of 23S rRNA methyltransferases [cfr and cfr(B)] and ABC-F protein (OptrA) for their dissemination in clinically relevant gram-positive pathogens such as enterococci and streptococci (Sadowy, 2018). A comprehensive molecular investigation in both humans and veterinary subjects may be required to preserve this pivotal antibiotic for gram-positive bacterial infections. In this study, we determined the complete genome sequence of cfr(B)-positive LR E. faecalis KUB3006 and the plasmid carrying optrA, which is the first report of a Tn6218-like-embedded cfr(B)-positive E. faecalis clinical isolate.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study protocol was approved by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases in Japan (Approval No. 677) and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this manuscript. The consent form is held by the authors’ institution and is available for review.

Bacterial Strains

Enterococcus faecalis strain KUB3006 was isolated from the midstream urine of a 67-year-old patient during hospitalization on May 2nd, 2017. The patient was suffering from collagen disease under the treatment of steroid and other immunosuppressive agents; however, such immune-compromised status increased the susceptibility to successive infection. The MIC for all of the following antimicrobials was determined by the broth-dilution method using the CLSI criteria (M100-S28, 2018): LZD, linezolid; VCM, vancomycin; TEIC, teicoplanin; ABK, arbekacin; TOB, tobramycin; LVFX, levofloxacin; AMP, ampicillin; IPM, imipenem; EM, erythromycin; SPM, spectinomycin; CLDM, clindamycin; CP, chloramphenicol.

Whole-Genome Sequence Analysis

Genomic DNA from E. faecalis was purified as follows. Bacterial cells were collected from a 5-mL overnight culture suspended in 500 μL TE10 [10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 10 mM EDTA]. The cell suspension was supplemented with 500 μL phenol/chloroform, followed by bead-beating for 10 min by vortexing in ZR BashingBead lysis tubes (Zymoresearch, Irvine, CA, United States) attached to a vortex adapter (Mo Bio Laboratories, Qiagen, Carlsbad, CA, United States). After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min, the upper phase was further purified using a Qiagen DNA purification kit (Qiagen). A DNA-seq library (approximately 0.5-kb inserts) was constructed using a QIAseq FX DNA Library Kit (Qiagen). Whole-genome sequencing was performed using the Illumina NextSeq 500 platform with the 300-cycle NextSeq 500 Reagent Kit v2 with paired-end read sequencing (2 × 150-mer; median coverage: 268×).

The complete genome sequences of the strain was determined using the long-read sequencing method of the PacBio Sequel sequencer [Sequel SMRT Cell 1M v2 (4/tray); Sequel Sequencing Kit v2.1; insert size, approximately 10 kb]. Purified genomic DNA (∼200 ng) was used to prepare a SMRTbell library using a SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0 (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA, United States) with barcoded adaptors according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing data were produced with more than 100-fold coverage and assembled using the following programs: Canu version 1.4 (Koren et al., 2017), Minimap version 0.2-r124 (Li, 2016), Racon version 1.1.0 (Vaser et al., 2017), and Circlator version 1.5.3 (Hunt et al., 2015). Error correction of tentative complete circular sequences was performed using Pilon version 1.18 with Illumina short reads (Walker et al., 2014). Annotation was performed in Prokka version 1.11 (Seemann, 2014), InterPro v49.0 (Finn et al., 2017), and NCBI-BLASTP/BLASTX.

Circular representations of complete genomic sequences were visualized using the GView server (Petkau et al., 2010). Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes were identified by homology searching against the ResFinder database (Zankari et al., 2012). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed using SRST2 (Inouye et al., 2014). Virulence factors for Enterococcus spp. were predicted using VirulenceFinder analysis (Kleinheinz et al., 2014).

Comparative Genome Sequence Analysis

All publicly available draft genome sequences of E. faecalis strains were retrieved (>2,000 strains with least 40× read coverage) and compared by using bwaMEM to map reads to the E. faecalis KUB3006 complete genome sequence (GenBank ID: AP018538) as a reference. Repeat regions were identified and excluded from further core-genome phylogenetic analysis using NUCmer (Kurtz et al., 2004), as these single-nucleotide variation (SNV) sites are considered unreliable. The core genome SNV analysis was performed using the maximum likelihood phylogenetic method with FastTree v2.1.10. Comparative Tn sequence analysis was performed with a BLASTN search (≥80% nt identity), followed by visualization using Easyfig v2.2.2 (Sullivan et al., 2011).

The cfr(B) gene SNV analysis was conducted using the median joining network method with PopART (Leigh and Bryant, 2015).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The complete genomic sequences and annotations of E. faecalis strain KUB-3006 were deposited in a public database DDBJ: chromosome (GenBank ID: AP018538); pKUB3006-1 (GenBank ID: AP018539); pKUB3006-2 (GenBank ID: AP018540); pKUB3006-3 (GenBank ID: AP018541); and pKUB3006-4 (GenBank ID: AP018542). The short- and long-read DNA sequences have been deposited in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive under accession number DRA006641 (BioProject: PRJDB6823, BioSample: SAMD00113788-SAMD00113789, and Experiment: DRX11916-DRX119165).

Results

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Compared with the E. faecalis type strain ATCC 29212 as a standard, E. faecalis KUB3006 showed resistance to LZD, ABK, TOB, LVFX, EM, SPM, CLDM, and CP, but not to VCM, TEIC, or β-lactams (AMP and IPM). This suggests that KUB3006 exhibits susceptibility to glycopeptides (VCM and TEIC) but reduced susceptibility to LZD (MIC: 16 μg/mL) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test (MIC, μg/mL).

| Antimicrobial agents | E. faecalis KUB3006 | E. faecalis ATCC 29212 |

|---|---|---|

| LZD | 16 | 2 |

| VCM | 2 | 2 |

| TEIC | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| ABK | >128 | 32 |

| TOB | >128 | 16 |

| LVFX | >128 | 1 |

| AMP | 2 | 1 |

| IPM | 2 | 0.5 |

| EM | >64 | 2 |

| SPM | >128 | 1 |

| CLDM | >128 | 16 |

| CP | 64 | 8 |

LZD, linezolid; VCM, vancomycin; TEIC, teicoplanin; ABK, arbekacin; TOB, tobramycin; LVFX, levofloxacin; AMP, ampicillin; IPM, imipenem; EM, erythromycin; SPM, spectinomycin; CLDM, clindamycin; CP, chloramphenicol.

Basic Genome Information for KUB3006

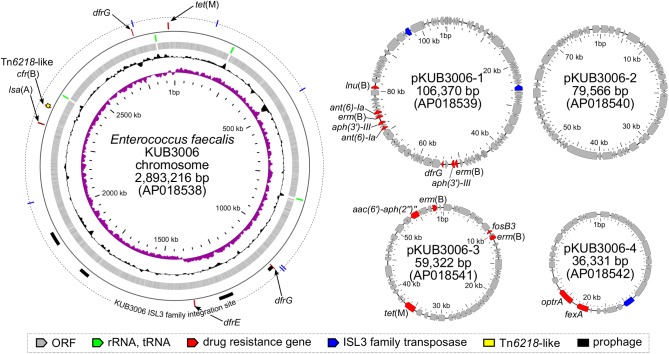

Basic information related to the complete genome sequence of E. faecalis strain KUB3006 is shown in Figure 1. To characterize the LZD resistance of this strain, potential mutations in the 23S rRNA genes, ribosomal protein genes (rplC, rplD, and rplV), and cfr 23S rRNA methylase gene were investigated, but no notable genetic features were identified. However, KUB3006 possesses the cfr variant cfr(B) on the chromosome, as well as four plasmids carrying multiple AMR genes, including optrA on pKUB3006-4 (36.3 kb) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Circular representation of the LR E. faecalis KUB3006 genome (chromosome and four plasmids). Moving inward in the chromosome circular map, slots 1–4 (slot 1, GC skew; slot 2, GC content; slot 3, open reading frames; slot 4, RNAs), slot 5 (prophage, AMR gene), and slot 6 (insertion sites of IS L3 family in KUB3006).

Genome analysis of the complete chromosomal DNA using SRST2 indicated that KUB3006 is classified as sequence type (ST) 729. VirulenceFinder analysis (Kleinheinz et al., 2014) demonstrated that KUB3006 carries multiple cell-adhesion properties [biofilm formation proteins (ebpA, ebpC, fsrB); adhesin to collagen (ace); an internalin-like Enterococcal leucine-rich protein A (elrA)] and cell-damaging factors [zinc-metalloprotease (gelE) for host collagen, fibrinogen, and fibrin; hyaluronidase (hylA and hylB)] (Table 2). In addition, multiple sex pheromones (camE, cOB1, cAD1, and cCF10) on its chromosome and two aggregation substances (agg) in two plasmids (pKUB3006-1 and pKUB3006-2) were found for conjugative transfer of plasmid (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prediction of virulence factors in LR E. faecalis KUB3006 by VirulenceFinder.

| Virulence factor | Identity (%) | Query/Template length (nt) | E. faecalis KUB3006 genome (GenBank ID) | Position in genome | Protein function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesin and aggregation | |||||

| ace | 95.71 | 2166/2166 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 903926..906091 | Collagen adhesin precursor |

| ebpA | 99.58 | 3312/3312 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 891588..894899 | Endocarditis and biofilm-associated pili for adherence to fibrinogen |

| ebpC | 99.58 | 1884/1884 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 896330..898213 | Endocarditis and biofilm-associated pili for adherence to fibrinogen |

| efaAfs | 100 | 927/927 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 1820636..1821562 | Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis antigen |

| ElrA | 99.91 | 2172/2172 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 2275786..2277957 | Enterococcal Leucine Rich protein A, an internalin-like protein |

| fsrB | 99.59 | 729/729 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 1629581..1630309 | Biofilm formation |

| SrtA | 99.18 | 735/735 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 2570541..2571275 | Sortase |

| Degrading enzyme | |||||

| gelE | 100 | 1530/1530 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 1626474..1628003 | Gelatinase |

| hylA | 99.33 | 3266/3264 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 2547513..2550777 | Hyaluronidase |

| hylB | 99.4 | 3015/3015 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 601784..604798 | Hyaluronidase |

| tpx | 99.22 | 510/510 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 2470693..2471202 | Lipid hydroperoxide peroxidase |

| Sex pheromone and aggregation | |||||

| camE | 99.4 | 501/501 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 1159865..1160365 | Sex pheromone cAM373 |

| cOB1 | 99.39 | 819/819 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 2128279..2129097 | Sex pheromone cOB1 |

| cad | 99.78 | 930/930 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 2785668..2786597 | Sex pheromone cAD1 |

| cCF10 | 99.76 | 828/828 | Chromosome (AP018538.1) | 2891232..2892059 | Sex pheromone cCF10 |

| agg | 95.64 | 3920/3918 | Plasmid pKUB3006-1 (AP018539.1) | 15542..19459 | Aggregation substance |

| agg | 93.52 | 3918/3906 | Plasmid pKUB3006-2 (AP018540.1) | 9883..13779 | Aggregation substance |

Core Genome Phylogenetic Analysis of KUB3006

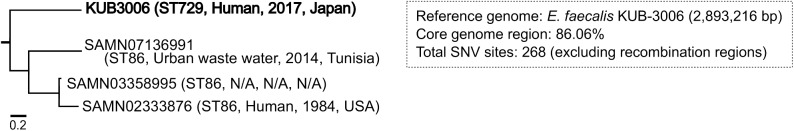

To trace the potential source of the KUB3006 strain, we performed core genome phylogenetic analysis using > 2,000 publicly available E. faecalis genome sequences, including draft genomes. Among the core-genome sequences, a total of 268 SNVs were identified with the more relative E. faecalis three strains (Figure 2). The phylogeny indicated that KUB3006 belonged to a similar lineage as ST86 E. faecalis strains carrying optrA-positive plasmid (pAF379, GenBank assembly ID: GCA_002220885.1) isolated from urban wastewater in Tunisia and human clinical specimens isolated in 1984 in the United States (Figure 2). However, this phylogeny-based analysis did not reveal the source of KUB3006, indicating that further genome sequences are required to determine a common source of the strain.

FIGURE 2.

Maximum likelihood core genome phylogeny of E. faecalis KUB3006. The core genome phylogeny of E. faecalis isolates, including KUB3006, using the maximum-likelihood method.

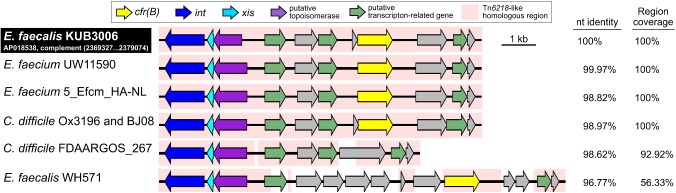

cfr(B) in the Tn6218-Like Tn

The cfr(B) gene was located in the Tn6218-like Tn element (2,369,327–2,379,074 nt on the KUB3006 chromosome in Figure 3). Comparative structural analysis of the Tn6218-like element of KUB3006 suggested that it is almost identical to the Tn6218-like element present in E. faecium and C. difficile strains, rather than showing similarity to other E. faecalis Tn (Figure 3). This implies that the KUB3006, E. faecium, and C. difficile strains acquired the cfr(B)-positive Tn6218-like element from a common source. Moreover, the Tn6218-like element of KUB3006 did not perfectly match that of E. faecalis WH571, indicating that Tn6218-like elements in Enterococcus display variable Tn structures (Figure 3), although all of these elements carry cfr(B). Surprisingly, the Tn6218-like element of KUB3006 was 98.97% identical to the notable C. difficile Ox3196 strain isolated from a human in the United Kingdom in 2012 (Dingle et al., 2014) (Figure 3). The C. difficile BJ08 strain, which was isolated from a human in China in 2008, also carries a Tn6218-like element (GenBank ID: CP003939.1) identical to that of Ox3196, while C. difficile FDAARGOS_267 carries an element with the basic Tn structure without cfr(B).

FIGURE 3.

Representation of the structure of cfr(B)-positive Tn6218-related Tns. Structural organization of a Tn6218-like Tn carrying cfr(B) in E. faecalis KUB3006 and the nucleotide identity compared with those of related Tns in C. difficile clinical isolates and Enterococcus species isolates.

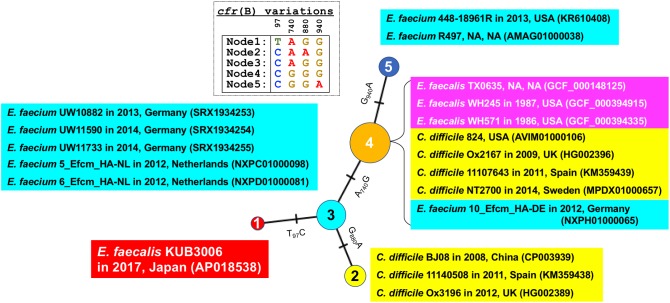

In addition, SNV analysis of the cfr(B) gene confirmed that the KUB3006 cfr(B) gene is more similar to those present in E. faecium strains isolated in EU countries from 2012 to 2014 than it is to other E. faecalis cfr(B) homologs (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Median joining network analysis of the cfr(B) nucleotide sequence. Bacterial species, strain, isolation year, country and the GenBank ID (or assembly ID) are shown at the branch. Four SNV sites [97, 740, 880, and 940 nt position in cfr(B)] were highlighted as Table.

OptrA Ribosomal Protection Protein

A homology search for AMR genes revealed the LZD resistance gene optrA, which encodes an ABC-F subfamily ATP-binding cassette protein, on the plasmid pKUB3006-4 (36.3 kb) (Figure 1). pKUB3006-4 is identical in size and sequence (except for a 2-nt mismatch) to plasmid p6742_1 (GenBank ID: KY513280.1) of the LR E. faecalis strain 6742, which was isolated from a clinical pus specimen in 2012 in Poland (Gawryszewska et al., 2017). Polish LR E. faecalis strains primarily have G2576T 23S rRNA mutations and the additional plasmid-borne optrA gene but carry neither the cfr nor cfr(B) methyltransferases. Furthermore, pKUB3006-4 showed similarity to the pE394 plasmid (deposited as a partial sequence, GenBank ID: KP399637.1), which was previously identified in China in both clinical and livestock E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates (Wang et al., 2015), suggesting that this optrA-positive plasmid has been globally disseminated among Enterococcus species.

Other Potential AMR Genes

In addition to cfr(B) and optrA, pKUB3006-1 (106.3 kb) carries multiple AMR genes, including ant(6)-Ia, aph(3′)-III, dfrG, erm(B), and lnu(B) (Figure 1). It has a similar backbone, with a 51% overlap, to the vanA-positive pTW9 plasmid in vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis (85.0 kb, GenBank ID: AB563188.1), which was isolated from poultry in Taiwan.

pKUB3006-2 (79.5 kb) carries no notable AMR genes (Figure 1) and has a similar backbone, with a 42% overlap, to the E. faecalis plasmid pGTC3 (GenBank ID: KY303941.1), which was isolated from the fecal material of a blue whale.

pKUB3006-3 (59.3 kb) carries multiple AMR genes, including aac(6′)-aph(2′), erm(B), fosB3, and tet(M) (Figure 1) and has a similar backbone, with a 52% overlap, to the E. faecalis plasmid pRE25 DNA (50.2 kb, GenBank ID: X92945.2), which was isolated from dry sausage in the EU (Schwarz et al., 2001).

Discussion

In this study, we completed the whole-genome sequencing of an LR E. faecalis clinical isolate and revealed that this strain carries the notable cfr(B) 23S methyltransferase gene in a Tn6218-like element that is almost identical to a Tn from LR E. faecium and C. difficile strains. This is the first report of an E. faecalis isolate carrying a cfr(B)-associated Tn with a structural organization similar to that of a C. difficile Tn6218-like element. This structural comparison strongly suggests that E. faecalis KUB3006, C. difficile, and E. faecium may have acquired the Tn6218-like element under LZD treatment from a common source. Alternatively, this could represent a mutual horizontal Tn transfer between Enterococcus and C. difficile through phenicol selective pressure in a veterinary environment.

In general, the Tn6218-like elements in C. difficile are associated with a 19-kb pathogenicity locus (PaLoc) (Braun et al., 1996) that contains two large clostridial toxin genes (tcdA and tcdB) (Kuehne et al., 2010). The population structure of C. difficile consists of five clades based on PaLoc analysis (Dingle et al., 2014), and C. difficile Ox3196 is classified into PaLoc Clade 4. The cfr(B)-related Tn6218-like elements exhibit the variable acquisition of multiple AMR genes, including cfr(B), in a clade-independent manner (Dingle et al., 2014), suggesting that Tn6218 elements occasionally contain genes conferring resistance to clinically relevant antibiotics in C. difficile.

In addition, analysis of E. faecalis KUB3006 revealed plasmids carrying multiple AMR genes, including optrA. Plasmid-mediated oxazolidinone resistance has been strongly linked to animal sources, in which the use of phenicols may co-select for resistance to both antibiotic families. Tamang et al. reported that in Korea, most LR Enterococcus isolates were also highly resistant to chloramphenicol and florfenicol, with no mutations in the 23S ribosomal RNA or in the ribosomal protein L3. In addition, these isolates did not carry cfr but were highly optrA-positive (Tamang et al., 2017). The optrA gene has been widely detected both in food-borne animals (poultry, pigs, and cattle) and clinical isolates in E. faecalis and E. faecium, whose STs belong to variable sequence types (Torres et al., 2018), indicating that optrA could be predominant resistance gene for LR Enterococcus species. Thus far, multiple optrA variants have been identified even in unrelated bacterial strains. Each optrA variant was located on the plasmids with the most identical background, indicating that the dissemination of optrA could be significantly involved in conjugative plasmid transfer (Bender et al., 2018). These observations suggest that KUB3006 may have initially acquired plasmid-mediated LZD resistance, followed by the acquisition of cfr(B).

Florfenicol is extensively used in livestock to prevent or cure bacterial infections. However, it is not known whether the administration of florfenicol has resulted in the emergence and dissemination of florfenicol resistance genes (FRGs, including fexA, fexB, cfr, optrA, floR, and pexA) in microbial populations in surrounding farm environments (Zhao et al., 2016). Zhao et al. (2016) detected FRGs and florfenicol residue in samples from six swine farms with a record of florfenicol usage. These authors concluded that the spreading of soils with swine waste could promote the prevalence and abundance of FRGs, including the LZD resistance genes cfr, cfr(B), and optrA.

Regarding the pathogenicity of E. faecalis, MLST analysis of EU strains indicated that multidrug resistance is common in the specific clonal complex (CC), in particular, the CC2, CC16, and CC87 lineages, whereas the CC2 and CC87 lineages were nearly exclusively observed in hospitals as potential “high-risk” E. faecalis lineages (Kawalec et al., 2007; Freitas et al., 2009; Willems et al., 2011; Kuch et al., 2012). However, KUB3006 is classified as ST729, which is a very minor ST. Considering that ST729 E. faecalis has not been reported previously, its complete genome sequence might uncover that KUB3006 carries multiple cell-adhesins, cell-damaging factors, sex pheromones, and aggregation substances (Table 2) that are characterized as pivotal virulence factors for infective endocarditis (Madsen et al., 2017). Although KUB3006 was isolated from a urine specimen of an immune-compromised patient with the successive infection, it might be a high virulent strain based on the identified set of Enterococcal virulence factors.

Potentially virulent E. faecalis KUB3006 strain harbors multiple LZD resistance determinants, cfr(B) and optrA, which contribute to LZD resistance (MIC: 16 μg/mL, Table 1). Indeed, the cfr(B)-positive E. faecium strains have been reported to exhibit an LZD MIC at 8 μg/mL (Deshpande et al., 2015), while optrA-positive E. faecalis strains have been reported to exhibit rather low MIC between 2 to 8 μg/mL (Torres et al., 2018). This suggests that KUB3006 might exhibit high MIC with multiple factors by cfr(B) and optrA, although the individual contribution of each gene remains to be investigated.

Conclusion

The LR E. faecalis KUB3006 possesses a notable Tn6218-like-borne cfr(B) and plasmid-borne optrA, and this finding raises further concerns regarding the possible declining effectiveness of LZD treatment in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The complete genomic sequences and annotations of E. faecalis strain KUB-3006 were deposited in a public database DDBJ: chromosome (AP018538); pKUB3006-1 (AP018539); pKUB3006-2 (AP018540); pKUB3006-3 (AP018541); and pKUB3006-4 (AP018542). The short- and long-read DNA sequences have been deposited in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive under accession number DRA006641 (BioProject: PRJDB6823, BioSample: SAMD00113788-SAMD00113789, and Experiment: DRX11916-DRX119165).

Author Contributions

KS, HS, and MS collected clinical specimens and isolated the strain from the patient. MK and TS performed the genome sequencing and the comparative genome analysis of E. faecalis KUB-3006. HM and HH contributed to the characterization of clinical isolates. MK wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (Grant Nos. JP17fk0108219 and JP17fk0108121). The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection, or analysis; decision to publish; or manuscript preparation.

References

- Antonelli A., D’Andrea M. M., Brenciani A., Galeotti C. L., Morroni G., Pollini S., et al. (2018). Characterization of poxtA, a novel phenicol-oxazolidinone-tetracycline resistance gene from an MRSA of clinical origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 10.1093/jac/dky088 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beganovic M., Luther M. K., Rice L. B., Arias C. A., Rybak M. J., LaPlante K. L. (2018). A review of combination antimicrobial therapy for Enterococcus faecalis bloodstream infections and infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 67 303–309. 10.1093/cid/ciy064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender J. K., Fleige C., Klare I., Fiedler S., Mischnik A., Mutters N. T., et al. (2016). Detection of a cfr(B) variant in German Enterococcus faecium clinical isolates and the impact on linezolid resistance in Enterococcus spp. PLoS One 11:e0167042. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender J. K., Fleige C., Lange D., Klare I., Werner G. (2018). Rapid emergence of highly variable and transferable oxazolidinone and phenicol resistance gene optrA in German Enterococcus spp. clinical isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.09.009 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Hundsberger T., Leukel P., Sauerborn M., von Eichel-Streiber C. (1996). Definition of the single integration site of the pathogenicity locus in Clostridium difficile. Gene 181 29–38. 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00398-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L., Wang Y., Lv Y., Wang S., Song Y., Li Y., et al. (2016). Nationwide surveillance of novel oxazolidinone resistance gene OPTRA in enterococcus isolates in China from 2004 to 2014. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 7490–7493. 10.1128/AAC.01256-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A., Bruun N. E. (2013). Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis: focus on clinical aspects. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 11 1247–1257. 10.1586/14779072.2013.832482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande L. M., Ashcraft D. S., Kahn H. P., Pankey G., Jones R. N., Farrell D. J., et al. (2015). Detection of a new cfr-like Gene, cfr(B), in Enterococcus faecium isolates recovered from human specimens in the United States as Part of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 6256–6261. 10.1128/AAC.01473-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz L., Kiratisin P., Mendes R. E., Panesso D., Singh K. V., Arias C. A. (2012). Transferable plasmid-mediated resistance to linezolid due to cfr in a human clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 3917–3922. 10.1128/AAC.00419-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle K. E., Elliott B., Robinson E., Griffiths D., Eyre D. W., Stoesser N., et al. (2014). Evolutionary history of the Clostridium difficile pathogenicity locus. Genome Biol. Evol. 6 36–52. 10.1093/gbe/evt204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone M., Russo A., Venditti M. (2015). Optimizing antibiotic therapy of bacteremia and endocarditis due to staphylococci and enterococci: new insights and evidence from the literature. J. Infect. Chemother. 21 330–339. 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Attwood T. K., Babbitt P. C., Bateman A., Bork P., Bridge A. J., et al. (2017). InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 D190–D199. 10.1093/nar/gkw1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A. R., Novais C., Ruiz-Garbajosa P., Coque T. M., Peixe L. (2009). Clonal expansion within clonal complex 2 and spread of vancomycin-resistant plasmids among different genetic lineages of Enterococcus faecalis from portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63 1104–1111. 10.1093/jac/dkp103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawryszewska I., Zabicka D., Hryniewicz W., Sadowy E. (2017). Linezolid-resistant enterococci in Polish hospitals: species, clonality and determinants of linezolid resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36 1279–1286. 10.1007/s10096-017-2934-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T., Wang Y., Schwarz S., Zhao Q., Shen J., Wu C. (2014). Genetic environment of the multi-resistance gene cfr in methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci from chickens, ducks, and pigs in China. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 304 257–261. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt M., Silva N. D., Otto T. D., Parkhill J., Keane J. A., Harris S. R. (2015). Circlator: automated circularization of genome assemblies using long sequencing reads. Genome Biol. 16:294. 10.1186/s13059-015-0849-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye M., Dashnow H., Raven L. A., Schultz M. B., Pope B. J., Tomita T., et al. (2014). SRST2: rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med. 6:90. 10.1186/s13073-014-0090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawalec M., Pietras Z., Danilowicz E., Jakubczak A., Gniadkowski M., Hryniewicz W., et al. (2007). Clonal structure of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from Polish hospitals: characterization of epidemic clones. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45 147–153. 10.1128/JCM.01704-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrenberg C., Schwarz S., Jacobsen L., Hansen L. H., Vester B. (2005). A new mechanism for chloramphenicol, florfenicol and clindamycin resistance: methylation of 23S ribosomal RNA at A2503. Mol. Microbiol. 57 1064–1073. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04754.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klare I., Fleige C., Geringer U., Thurmer A., Bender J., Mutters N. T., et al. (2015). Increased frequency of linezolid resistance among clinical Enterococcus faecium isolates from German hospital patients. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 3 128–131. 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinheinz K. A., Joensen K. G., Larsen M. V. (2014). Applying the resfinder and virulencefinder web-services for easy identification of acquired antibiotic resistance and E. coli virulence genes in bacteriophage and prophage nucleotide sequences. Bacteriophage 4:e27943. 10.4161/bact.27943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloss P., Xiong L., Shinabarger D. L., Mankin A. S. (1999). Resistance mutations in 23 S rRNA identify the site of action of the protein synthesis inhibitor linezolid in the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center. J. Mol. Biol. 294 93–101. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S., Walenz B. P., Berlin K., Miller J. R., Bergman N. H., Phillippy A. M. (2017). Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27 722–736. 10.1101/gr.215087.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuch A., Willems R. J., Werner G., Coque T. M., Hammerum A. M., Sundsfjord A., et al. (2012). Insight into antimicrobial susceptibility and population structure of contemporary human Enterococcus faecalis isolates from Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 551–558. 10.1093/jac/dkr544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne S. A., Cartman S. T., Heap J. T., Kelly M. L., Cockayne A., Minton N. P. (2010). The role of toxin A and toxin B in clostridium difficile infection. Nature 467 711–713. 10.1038/nature09397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., Phillippy A., Delcher A. L., Smoot M., Shumway M., Antonescu C., et al. (2004). Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 5:R12. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh J. W., Bryant D. (2015). POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6 1110–1116. 10.1111/2041-210X.12410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (2016). Minimap and miniasm: fast mapping and de novo assembly for noisy long sequences. Bioinformatics 32 2103–2110. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Jiang N., Ke Y., Fessler A. T., Wang Y., Schwarz S., et al. (2017). Characterization of pig-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Vet. Microbiol. 201 183–187. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang Y., Wu C., Shen Z., Schwarz S., Du X. D., et al. (2012). First report of the multidrug resistance gene cfr in Enterococcus faecalis of animal origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 1650–1654. 10.1128/AAC.06091-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long K. S., Poehlsgaard J., Kehrenberg C., Schwarz S., Vester B. (2006). The Cfr rRNA methyltransferase confers resistance to phenicols, lincosamides, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin a antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 2500–2505. 10.1128/AAC.00131-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- M100-S28 (2018). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: 28th Informational Supplement. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen K. T., Skov M. N., Gill S., Kemp M. (2017). Virulence factors associated with Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis: a mini review. Open Microbiol. J. 11 1–11. 10.2174/1874285801711010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin M., Martin A., Alcala L., Cercenado E., Iglesias C., Reigadas E., et al. (2015). Clostridium difficile isolates with high linezolid MICs harbor the multiresistance gene cfr. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 586–589. 10.1128/AAC.04082-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes R. E., Deshpande L. M., Jones R. N. (2014). Linezolid update: stable in vitro activity following more than a decade of clinical use and summary of associated resistance mechanisms. Drug Resist. Updat. 17 1–12. 10.1016/j.drup.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkau A., Stuart-Edwards M., Stothard P., Van Domselaar G. (2010). Interactive microbial genome visualization with GView. Bioinformatics 26 3125–3126. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Mendes R. E., Streit J. M., Hogan P. A., Flamm R. K. (2017a). Five-year summary of in vitro activity and resistance mechanisms of linezolid against clinically important gram-positive cocci in the united states from the leader surveillance program (2011 to 2015). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61 e609–e617. 10.1128/AAC.00609-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Mendes R. E., Streit J. M., Hogan P. A., Flamm R. K. (2017b). ZAAPS Program results for 2015: an activity and spectrum analysis of linezolid using clinical isolates from medical centres in 32 countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 3093–3099. 10.1093/jac/dkx251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowy E. (2018). Linezolid resistance genes and genetic elements enhancing their dissemination in enterococci and streptococci. Plasmid 10.1016/j.plasmid.2018.09.011 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder S. M., Dong Y., Fessler A. T., Schwarz S., Schoen C., Kock R., et al. (2017). Antibiotic resistance profiles of coagulase-negative staphylococci in livestock environments. Vet. Microbiol. 200 79–87. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz F. V., Perreten V., Teuber M. (2001). Sequence of the 50-kb conjugative multiresistance plasmid pRE25 from Enterococcus faecalis RE25. Plasmid 46 170–187. 10.1006/plas.2001.1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S., Werckenthin C., Kehrenberg C. (2000). Identification of a plasmid-borne chloramphenicol-florfenicol resistance gene in Staphylococcus sciuri. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44 2530–2533. 10.1128/AAC.44.9.2530-2533.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30 2068–2069. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey L. K., Edwards T. A., O’Neill A. J. (2016). ABC-F proteins mediate antibiotic resistance through ribosomal protection. mBio 7:e01975. 10.1128/mBio.01975-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W., Kumar V., Ding Y., Ero R., Serra A., Lee B. S. T., et al. (2018). Ribosome protection by antibiotic resistance ATP-binding cassette protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 5157–5162. 10.1073/pnas.1803313115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. J., Petty N. K., Beatson S. A. (2011). Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27 1009–1010. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamang M. D., Moon D. C., Kim S. R., Kang H. Y., Lee K., Nam H. M., et al. (2017). Detection of novel oxazolidinone and phenicol resistance gene optrA in enterococcal isolates from food animals and animal carcasses. Vet. Microbiol. 201 252–256. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh S. M., Xiong L., Arias C. A., Villegas M. V., Lolans K., Quinn J., et al. (2007). Acquisition of a natural resistance gene renders a clinical strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resistant to the synthetic antibiotic linezolid. Mol. Microbiol. 64 1506–1514. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05744.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres C., Alonso C. A., Ruiz-Ripa L., Leon-Sampedro R., Del Campo R., Coque T. M. (2018). Antimicrobial resistance in Enterococcus spp. of animal origin. Microbiol. Spectr. 6 1–41. 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0032-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaser R., Sovic I., Nagarajan N., Sikic M. (2017). Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27 737–746. 10.1101/gr.214270.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J., Abeel T., Shea T., Priest M., Abouelliel A., Sakthikumar S., et al. (2014). Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Lv Y., Cai J., Schwarz S., Cui L., Hu Z., et al. (2015). A novel gene, optrA, that confers transferable resistance to oxazolidinones and phenicols and its presence in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium of human and animal origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70 2182–2190. 10.1093/jac/dkv116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems R. J., Hanage W. P., Bessen D. E., Feil E. J. (2011). Population biology of gram-positive pathogens: high-risk clones for dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35 872–900. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00284.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte W., Cuny C. (2011). Emergence and spread of cfr-mediated multiresistance in staphylococci: an interdisciplinary challenge. Future Microbiol. 6 925–931. 10.2217/FMB.11.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahedi Bialvaei A., Rahbar M., Yousefi M., Asgharzadeh M., Samadi Kafil H. (2017). Linezolid: a promising option in the treatment of Gram-positives. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 354–364. 10.1093/jac/dkw450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 2640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Wang Y., Wang S., Wang Z., Du X. D., Jiang H., et al. (2016). Prevalence and abundance of florfenicol and linezolid resistance genes in soils adjacent to swine feedlots. Sci. Rep. 6:32192. 10.1038/srep32192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The complete genomic sequences and annotations of E. faecalis strain KUB-3006 were deposited in a public database DDBJ: chromosome (AP018538); pKUB3006-1 (AP018539); pKUB3006-2 (AP018540); pKUB3006-3 (AP018541); and pKUB3006-4 (AP018542). The short- and long-read DNA sequences have been deposited in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive under accession number DRA006641 (BioProject: PRJDB6823, BioSample: SAMD00113788-SAMD00113789, and Experiment: DRX11916-DRX119165).