Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are involved in numerous processes during infections by both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. Among them, herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) modulates secretory pathways, allowing EVs to exit infected cells. Many characteristics regarding the mechanisms of viral spread are still unidentified, and as such, secreted vesicles are promising candidates due to their role in intercellular communications during viral infection. Another relevant role for EVs is to protect virions from the action of neutralizing antibodies, thus increasing their stability within the host during hematogenous spread. Recent studies have suggested the participation of EVs in HSV-1 spread, wherein virion-containing microvesicles (MVs) released by infected cells were endocytosed by naïve cells, leading to a productive infection. This suggests that HSV-1 might use MVs to expand its tropism and evade the host immune response. In this review, we briefly describe the current knowledge about the involvement of EVs in viral infections in general, with a specific focus on recent research into their role in HSV-1 spread. Implications of the autophagic pathway in the biogenesis and secretion of EVs will also be discussed.

Keywords: extracellular vesicles, microvesicles, exosomes, viral spread, immune evasion, HSV-1, autophagy

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are a heterogeneous group of membrane vesicles, derived from endosomes or from the plasma membrane, secreted by almost all cell types belonging to the three domains of cellular life: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya (Yañez-Mo et al., 2015; Sedgwick and D’Souza-Schorey, 2018; van Niel et al., 2018). EVs have been isolated from numerous biological fluids such as blood, saliva, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, amniotic fluid, ascetic fluid, breast milk, and seminal fluid (Yañez-Mo et al., 2015; Zaborowski et al., 2015; Kalra et al., 2016). Initially considered to be mostly cell debris, EVs have now emerged as key mediators of intercellular communication, and are currently associated with numerous physiological and pathological processes (Gyorgy et al., 2011; van der Pol et al., 2012; Yuana et al., 2013) such as cancer (Muralidharan-Chari et al., 2010; Barros et al., 2018; Nogues et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018), infection (Silverman and Reiner, 2011; Lai et al., 2015; Schorey et al., 2015), inflammation and immune response (Robbins et al., 2016), and myelination and neuron-glia communication (Fruhbeis et al., 2013; Basso and Bonetto, 2016; Lopez-Leal and Court, 2016; Pusic et al., 2016; Holm et al., 2018).

Although the classification and nomenclature of EVs is complex, two major categories of EVs can be broadly established: (1) microvesicles (MVs) derived from shedding of the plasma membrane (Cocucci et al., 2009; Cocucci and Meldolesi, 2015); and (2) exosomes, vesicles released to the extracellular space upon fusion of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with the plasma membrane (Colombo et al., 2014; Yañez-Mo et al., 2015; Maas et al., 2017). While exosomes are between 30 and 100 nm in diameter, MVs are much more heterogeneous, ranging from 100 nm to 1 μm in diameter (Raposo and Stoorvogel, 2013; Yuana et al., 2013). MVs are enriched in lipid rafts and commonly associated proteins such as flotillin-1, and expose phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer plasma membrane leaflet (Scott et al., 1984; Del Conde et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2016). Exosomes, on the other hand, are enriched in tetraspanins (CD9, CD63 and CD81, among others), which are frequently used as exosomal markers (Andreu and Yañez-Mo, 2014) and also in endosomal markers such as ALIX and TSG101 (Kowal et al., 2016; Willms et al., 2016). Although the presence of PS exposed in exosomes has been postulated (Thery et al., 2009; Colombo et al., 2014; De Paoli et al., 2018) other studies question that exosomes expose PS just after secretion from cells (Lai R.C. et al., 2016; Skotland et al., 2017), remaining this point to be fully clarified.

Extracellular vesicles are also involved in viral infection (Meckes and Raab-Traub, 2011; Wurdinger et al., 2012; Alenquer and Amorim, 2015; Altan-Bonnet, 2016; Anderson et al., 2016), influencing viral entry, spread and immune evasion (Schorey et al., 2015; Kouwaki et al., 2017). Thus, EVs operate as an important system of intercellular communication between infected and uninfected cells (Meckes, 2015; Raab-Traub and Dittmer, 2017). Indeed, due to their common biogenesis pathways, EVs and viruses are considered to be close relatives, and EVs secreted by infected cells can either enhance viral spread or, on the contrary, trigger an antiviral response (Nolte-’T Hoen et al., 2016). The great variability of the role of EVs during the viral life cycle is evident, as they can produce such opposite effects as the blockage or increase of infection, as well as modulate the immune response (Wurdinger et al., 2012). Two key biological activities of EVs during viral infections are the transport of viral genomes into target cells and the intervention in cell physiology to facilitate infection (van Dongen et al., 2016).

This review will briefly describe the current knowledge about the involvement of EVs in viral infections, with a specific focus on recent research on their role in herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) spread.

Viruses and EVs

Extracellular vesicles have been implicated in numerous processes during infections by both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. For example, EVs play a relevant role in hepatitis C virus (HCV) spread, as virions contained in exosomes can be transported to hepatocyte-like cells, establishing a productive infection (Ramakrishnaiah et al., 2013). Likewise, the release of hepatitis A virus (HAV) enclosed in infectious EVs derived from cellular membranes (Feng et al., 2013) permits viral escape from antibodies and facilitates viral spread. Several picornaviruses can be transported in EVs; the secretion of exosomes containing enterovirus 71 (EV71) has been shown to establish a productive infection in human neuroblastoma cells (Mao et al., 2016), and coxsackievirus B can exit infected cells in MVs derived from mitophagosomes (Robinson et al., 2014; Sin et al., 2017). Gastroenteric pathogens such as noroviruses and rotaviruses have also been detected enclosed in EVs that can transfer a high inoculum to the next host, contributing, therefore, to fecal-oral transmission and enhancing the viral propagation (Santiana et al., 2018). Thus, infection with non-enveloped viruses can induce the release of MVs containing viral proteins and infectious virus, indicating novel routes of virus dissemination.

Human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) modulates vesicle secretion through its Nef protein, which is secreted in exosomes and modifies the intracellular trafficking pathways to enhance viral infectivity (Lenassi et al., 2010; Pereira and daSilva, 2016). For retroviruses in general, the Trojan exosome hypothesis states that these viruses use the cellular exosome biogenesis pathway for formation of infectious virions and the exosome uptake pathway for a receptor-independent, Env-independent route of infection (Gould et al., 2003). According to this model, dendritic cells (DCs) capture and internalize retroviruses by endocytosis and, subsequently, some of the non-degraded virions may infect the DC-interacting CD4+ T cells, contributing to viral spread through a mechanism known as trans-infection. Both direct infection and trans-infection might coexist to a different extent depending on the maturation stage of DC subsets (Izquierdo-Useros et al., 2010).

Herpesviruses also modulate the secretion pathway of EVs to exit cells; in fact, the exosome pathway is exploited by the three subfamilies: alpha-, beta- and gamma- (Liu et al., 2017; Sadeghipour and Mathias, 2017). Thus, the secretion of exosomes by HSV-1-infected cells carrying viral RNA and stimulator of IFN genes (STING) to uninfected cells has recently been reported (Kalamvoki et al., 2014; Kalamvoki and Deschamps, 2016). The exosome secretion pathway also plays an important role in the life cycle of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), whose virions are released along with intraluminal vesicles via the exosomal pathway, by fusion of the limiting membrane of MVBs—in which virus particles and exosomes are enclosed—with the plasma membrane (Mori et al., 2008). A similar role for MVBs in the release of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) has been also suggested (Fraile-Ramos et al., 2007; Schauflinger et al., 2011). The human gamma-herpesviruses Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) also alter the protein content of exosomes, probably to modulate the tumor microenvironment, enhance viral efficiency and promote tumorigenesis (Vazirabadi et al., 2003; Meckes et al., 2010, 2013). In addition, exosomes can also transfer functional miRNAs from EBV-infected cells to subcellular sites of gene repression in uninfected recipient cells (Pegtel et al., 2010).

HSV-1: A Brief Overview

Herpes simplex virus type-1 is a highly prevalent neurotropic human pathogen belonging to the alphaherpesvirus subfamily that can infect neurons and establish latency in these cells (Roizman et al., 2011; Miranda-Saksena et al., 2018). HSV-1 causes oral, labial and, occasionally facial lesions, and is an increasingly important cause of sexually transmitted genital herpes (Horowitz et al., 2010; Bernstein et al., 2013), producing a significant percentage of cases (Wald and Corey, 2007). This virus may also cause serious pathologies such as encephalitis or keratoconjunctivitis (Whitley, 2006). HSV-1 infects epithelial cells and subsequently travels to neurons, establishing latent infection in the trigeminal ganglia.

Herpes simplex virus type-1 has the ability to infect many different host and cell types (Karasneh and Shukla, 2011), using several different receptors and pathways. This virus can enter cells by fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane, a pH-independent process, or by endocytosis, which can either be low pH-dependent or low pH-independent (Reske et al., 2007; Heldwein and Krummenacher, 2008; Akhtar and Shukla, 2009; Agelidis and Shukla, 2015; Nicola, 2016). Regardless of the pathway, HSV glycoproteins such as the receptor-binding glycoprotein D (gD), the fusion modulator complex gH/gL and the fusion effector gB are essential for virion entry. Maturation and egress follow four major stages: (a) capsid assembly and DNA packaging; (b) primary envelopment and de-envelopment; (c) tegumentation and secondary envelopment; (d) exocytosis of viral particles and/or cell-to-cell transmission (Owen et al., 2015). Secondary envelopment may also occur using the endocytic pathway, and in fact, it has been proposed that endocytosis from the plasma membrane into endocytic tubules represents the main source for HSV-1 envelopment (Hollinshead et al., 2012). According to this mode of envelopment, viral glycoproteins are exported to the plasma membrane via the secretory pathway and are subsequently endocytosed in endocytic tubules that are then used to wrap the viral nucleocapsid, forming the double-membraned intracellular virion (David, 2012; Hollinshead et al., 2012). This endocytic process is dynamin-dependent, and it plays a major role for transporting HSV-1 envelope proteins to intracellular sites of virus assembly (Albecka et al., 2016).

Herpes simplex virus type-1 may use several mechanisms to spread from infected to uninfected cells (Agelidis and Shukla, 2015). Several viral glycoproteins, such as the heterodimer gE/gI or glycoprotein gK, are necessary for release of virions from parent cells, and it has been recently reported that the host enzyme heparanase-1 is also required for viral release (Hadigal et al., 2015). On the other hand, HSV-1 can disseminate in human tissues by cell-to-cell spread—the direct passage of progeny virus from an infected cell to a neighboring one—, a mechanism that might be considered as an immune evasion strategy, since it protects the virus from immune surveillance (Campadelli-Fiume, 2007). However, many aspects concerning mechanisms of viral spread are still unidentified. In this context, secreted vesicles are interesting candidates to consider, because of their ability to participate in intercellular communications during viral infections.

HSV-1 and EVs

Production of secreted vesicles by HSV-1-infected cells has been previously reported. Light particles (L-particles) (Szilagyi and Cunningham, 1991; McLauchlan and Rixon, 1992), the first to be described, are vesicles secreted by human and animal cells after infection with every alpha-herpesviruses tested (Heilingloh and Krawczyk, 2017). They are similar to virions in appearance, but lack the viral nucleocapsid and genome (Szilagyi and Cunningham, 1991) and are thus non-infectious. L-particles have been shown to facilitate HSV-1 infection by transfer of viral proteins and cellular factors required for viral replication and also immune evasion (Dargan and Subak-Sharpe, 1997; Kalamvoki and Deschamps, 2016). Another type of particles, pre-viral DNA replication enveloped particles (PREPs), are morphologically similar to L-particles, but differ in their relative protein composition (Dargan et al., 1995).

As mentioned above, recent studies have shown that cells infected with HSV-1 can use exosomes to export STING to uninfected cells, along with virions, viral mRNAs, microRNAs and the exosome marker protein CD9. Those results suggested that HSV-1 might limit the spread of infection from cell-to-cell in order to control its virulence and facilitate the dissemination between individuals (Kalamvoki et al., 2014; Kalamvoki and Deschamps, 2016; Deschamps and Kalamvoki, 2018). On the other hand, previous studies carried out by our group indicated that Rab27a, a small GTPase implicated in exosomes secretion (Ostrowski et al., 2010), plays an important role in HSV-1 infection of oligodendrocytic cells (Bello-Morales et al., 2012). In fact, our results showed a drastic reduction not only in viral production, but also in plaque size of Rab27a-silenced cells infected with HSV-1, suggesting that Rab27a depletion might be affecting viral egress. In addition, this GTPase seems to affect the viral assembly of other viruses, such as HIV-1 (Gerber et al., 2015) and HCMV (Fraile-Ramos et al., 2010).

More recent findings (Bello-Morales et al., 2018) have suggested the participation of MVs in HSV-1 spread. Our study described the features of MVs released by the human oligodendroglial (HOG) cell line infected with HSV-1 and their participation in the viral cycle, indicating for the first time that MVs released by HSV-1-infected cells contained virions, were endocytosed by naïve cells, and led to a productive infection. This suggests that HSV-1 spread might use MVs to expand its tropism and possibly evade the host immune response (Bello-Morales et al., 2018).

EVs in Viral Immune Evasion

The release of virus from cells mediated by EVs plays a relevant role in viral spread and pathogenesis, and may help to expand the natural tropism of viruses to include target cells which lack canonical viral receptors. On the other hand, EVs may also transfer virus-encoded proteins and nucleic acids independently of the viral particles. For instance, both simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) (McNamara et al., 2018) and HIV-1 (Lenassi et al., 2010; Pereira and daSilva, 2016; Puzar Dominkus et al., 2017) induce the release of Nef protein in exosomes; EBV LMP1 is also secreted in EVs (Meckes et al., 2010; Nkosi et al., 2018) and functional exosomes containing miRNAs have been detected in human clinical samples and mouse models of KSHV-associated malignancies (Chugh et al., 2013).

However, EVs also have an equally important role: to protect virions against the action of neutralizing antibodies and thus increasing their stability within the host during hematogenous spread. In this sense, acquisition of an envelope can provide resistance to neutralizing antibodies, and therefore reinforce viral spread (Sin et al., 2015), since neutralizing antibodies would be ineffective against virions protected within vesicles (Robinson et al., 2014). Systemic circulation of viruses enclosed in EVs would allow them to modulate host cells without exposing their proteins or progeny virions to the immune system (Raab-Traub and Dittmer, 2017). This is especially relevant for non-enveloped viruses; thus, acquisition of an envelope helps coxsackievirus to evade the immune system, permitting an efficient non-lytic viral spread (Sin et al., 2015). But enveloped viruses may also benefit from MV-mediated spread, as HCV transmission is enhanced by exosomes (Masciopinto et al., 2004; Bukong et al., 2014), and HCV-related exosomes seem to be involved in immune escape (Shen et al., 2017). In fact, hepatic exosomes—partially resistant to antibody neutralization—can transport HCV to cells and establish a productive infection (Ramakrishnaiah et al., 2013). Likewise, HAV exploits EVs as vehicles to escape antibody-mediated neutralization (Feng et al., 2013).

Regarding HSV-1, it is accepted that this virus influences the EV pathway to enhance infection and/or evade the immune system. For example, it has been demonstrated that HSV-1 may manipulate the MHC class II processing pathway by altering the endosomal sorting and trafficking of HLA-DR, hijacking these molecules from normal transport pathways to the cell surface and diverting them into the exosome pathway (Temme et al., 2010). In addition, and as already mentioned, functional HSV-1 proteins can be transferred to uninfected cells via L-particles, a process that suggests a viral immune escape strategy (Heilingloh et al., 2015). Likewise, the results obtained in our laboratory have shown that infection of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with virus-containing MVs was not completely neutralized by anti-HSV-1 antibodies, suggesting that they shield the virus (Bello-Morales et al., 2018).

EVs and the Autophagic Pathway

Conventional autophagy is a eukaryotic degradative pathway in which cytoplasmic components are sequestered in autophagosomes that finally will fuse with the lysosome, degrading its contents by lysosomal hydrolases (Nakatogawa et al., 2009; Ohsumi, 2014). Autophagy plays an essential role in several physiological and pathological processes, such as xenophagy, the removal of intracellular pathogens including viruses (Wirawan et al., 2012). Autophagy significantly restrains HSV-1 infection in various cell types (Yakoub and Shukla, 2015), though some viruses have acquired the ability to modulate autophagy for their own benefit (Choi et al., 2018). In this way, HSV-1 and HIV interact with Beclin-1, thereby inhibiting autophagosome maturation (Orvedahl et al., 2007; Kyei et al., 2009).

Autophagy, however, may also have a non-degradative role: in secretory autophagy, a newly discovered pathway, autophagosomes fuse with the plasma membrane instead of lysosomes, releasing vesicles enclosing cytoplasmic cargo to the extracellular environment (Rabouille et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2013; Zhang and Schekman, 2013; Ponpuak et al., 2015).

Many other studies have shown that viruses may use autophagic Atg proteins for morphogenesis and viral egress (Munz, 2017), for example EBV (Lee and Sugden, 2008; Granato et al., 2014; Fotheringham and Raab-Traub, 2015; Hurwitz et al., 2018), varicella zoster virus (VZV) (Buckingham et al., 2016; Grose et al., 2016) or picornaviruses (Jackson et al., 2005; Taylor and Kirkegaard, 2008; Klein and Jackson, 2011; Robinson et al., 2014; Mutsafi and Altan-Bonnet, 2018). Coxsackievirus B, for instance, may use the autophagic pathway to exit cells enclosed in LC3-II-positive shedding MVs (Robinson et al., 2014), a process similar to the autophagosome-mediated exit without lysis (AWOL) observed in poliovirus (Taylor et al., 2009; Lai J.K. et al., 2016). According to this model, fusion between autophagosomes and endosomes generates amphisomes, LC3-II-positive vesicles enclosing viral particles which can fuse with the plasma membrane to secrete virions (Lai J.K. et al., 2016). Remarkably, due to the complexity of their replication cycles, viruses may exert a dual role on this kind of process: on one hand, subversion of autophagy in infected cells and on the other, induction of hyper-autophagy in bystander cells (Killian, 2012).

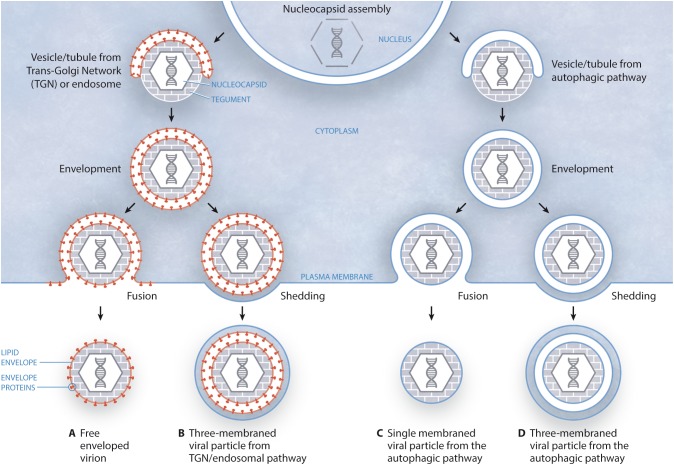

In a recent study carried out by our group (Bello-Morales et al., 2018) we have shown the presence of virions in MVs released by infected cells. Although the exact process of HSV-1 targeting to MVs remains to be fully unraveled, we suggested that autophagy may be involved in that process, since MVs isolated from HSV-1-infected cells were positive for the autophagy marker LC3-II. Therefore, these results suggest a role for the autophagic pathway in MV-mediated HSV-1 spread, although more data is necessary to confirm that crucial point. On the other hand, this particular study suggested different models of biogenesis and secretion of MV-associated HSV-1 depending on the cell type. According to the canonical model of HSV-1 egress, the nucleocapsid is wrapped in vesicles/tubules from trans-Golgi network (TGN)/endosomes, giving rise to an enveloped virion surrounded by a double membrane that, after fusion with the plasma membrane, gives rise to an extracellular free enveloped virion (Figure 1A). However, the egress of this structure by membrane shedding cannot be excluded, which would produce a three-membraned viral particle corresponding to an enveloped virion enclosed within a shedding MV (Figure 1B). Such triple-membraned virions have been observed upon infection of Mewo cells (Bello-Morales et al., 2018); however, nucleocapsids might also obtain their envelopes from the autophagic pathway. In this way, vesicles/tubules from the autophagic pathway would cover the nucleocapsid, giving rise to a viral particle surrounded by a double membrane. Then, this structure would reach the plasma membrane and, after fusion, a viral particle surrounded by a single membrane would exit the cell (Figure 1C). This type of structure has been observed upon infection of HOG and Hela cells (Bello-Morales et al., 2018). Alternatively, double-membraned particles might exit the cell not by fusion, but by shedding of the plasma membrane, originating a three-membraned viral particle (Figure 1D). Further work will have to unveil whether viral glycoproteins are targeted to vesicles/tubules from autophagic pathway (Figures 1C,D) before wrapping of nucleocapsids. Finally, our results highlight the relevance of the cellular model when attempting the study of viral modulation of autophagy and, as different cell types may give different autophagy responses, it can be difficult to directly compare different virus-cell systems, especially when studying viruses that infect more than one cell type (Lin et al., 2010).

FIGURE 1.

Models of biogenesis and secretion of MV-enclosed HSV-1 virions. (A) The canonical egress of HSV-1 entails the fusion of a two-membraned viral particle with the plasma membrane, giving rise to an extracellular free enveloped virion. In this model, the viral envelope is derived from the TGN/endosomes. (B) Alternatively, this structure might exit the cell after shedding of the plasma membrane, resulting in a three-membraned viral particle, which would correspond to an enveloped virion enclosed within a shedding MV. (C) According to this model, vesicles/tubules originating from the autophagic pathway wrap around the nucleocapsid, giving rise to a viral particle surrounded by a double membrane. Then, this structure would reach the plasma membrane and, after fusion, a viral particle surrounded by a single membrane would exit the cell. (D) In an alternative model, the two-membraned viral particle might exit the cell not by fusion, but by shedding of the plasma membrane, giving rise to a three-membraned viral particle.

Conclusion

Several herpesviruses may modulate the secretory pathway of EVs in order to enhance viral egress or evade the immune response. EVs may also increase viral stability during hematogenous spread by protecting virus from exposure to neutralizing antibodies. Recent studies have shown that MVs released by HSV-1 infected cells contained virions which were endocytosed by naïve cells, leading to a productive infection, suggesting that the virus uses EVs to expand its tropism and possibly evade the host immune response. In addition, growing evidence is demonstrating the importance of autophagy in viral infections, which several viruses use for morphogenesis and viral egress. We suggest that HSV-1 might use MVs for viral spread and propose different models of biogenesis and secretion of MVs-associated HSV-1 depending on the cell type.

Author Contributions

Both authors conceived and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fundamentium (https://fundamentium.com/) for infographics. The professional editing service NB Revisions was used for technical preparation of the text prior to submission.

Footnotes

Funding. Fundación Severo Ochoa-Aeromédica Canaria provided financial support. The funders had no role in study design, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Agelidis A. M., Shukla D. (2015). Cell entry mechanisms of HSV: what we have learned in recent years. Future Virol. 10 1145–1154. 10.2217/fvl.15.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar J., Shukla D. (2009). Viral entry mechanisms: cellular and viral mediators of herpes simplex virus entry. FEBS J. 276 7228–7236. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07402.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albecka A., Laine R. F., Janssen A. F., Kaminski C. F., Crump C. M. (2016). HSV-1 glycoproteins are delivered to virus assembly sites through dynamin-dependent endocytosis. Traffic 17 21–39. 10.1111/tra.12340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alenquer M., Amorim M. J. (2015). Exosome biogenesis, regulation, and function in viral infection. Viruses 7 5066–5083. 10.3390/v7092862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altan-Bonnet N. (2016). Extracellular vesicles are the Trojan horses of viral infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 32 77–81. 10.1016/j.mib.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. R., Kashanchi F., Jacobson S. (2016). Exosomes in viral disease. Neurotherapeutics 13 535–546. 10.1007/s13311-016-0450-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu Z., Yañez-Mo M. (2014). Tetraspanins in extracellular vesicle formation and function. Front. Immunol. 5:442. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros F. M., Carneiro F., Machado J. C., Melo S. A. (2018). Exosomes and immune response in cancer: friends or foes? Front. Immunol. 9:730. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso M., Bonetto V. (2016). Extracellular vesicles and a novel form of communication in the brain. Front. Neurosci. 10:127. 10.3389/fnins.2016.00127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Morales R., Crespillo A. J., Fraile-Ramos A., Tabares E., Alcina A., Lopez-Guerrero J. A. (2012). Role of the small GTPase Rab27a during herpes simplex virus infection of oligodendrocytic cells. BMC Microbiol. 12:265. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Morales R., Praena B., De La Nuez C., Rejas M. T., Guerra M., Galan-Ganga M., et al. (2018). Role of microvesicles in the spread of herpes simplex virus 1 in oligodendrocytic cells. J. Virol. 92:e00088-18. 10.1128/JVI.00088-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D. I., Bellamy A. R., Hook E. W., III, Levin M. J., Wald A., Ewell M. G., et al. (2013). Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56 344–351. 10.1093/cid/cis891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham E. M., Jarosinski K. W., Jackson W., Carpenter J. E., Grose C. (2016). Exocytosis of varicella-zoster virus virions involves a convergence of endosomal and autophagy pathways. J. Virol. 90 8673–8685. 10.1128/JVI.00915-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukong T. N., Momen-Heravi F., Kodys K., Bala S., Szabo G. (2014). Exosomes from hepatitis C infected patients transmit HCV infection and contain replication competent viral RNA in complex with Ago2-miR122-HSP90. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004424. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campadelli-Fiume G. (2007). “The egress of alphaherpesviruses from the cell,” in Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis, eds Arvin A., Campadelli-Fiume G., Mocarski E., Moore P. S., Roizman B., Whitley R., et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ), 151–163. 10.1017/CBO9780511545313.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Bowman J. W., Jung J. U. (2018). Autophagy during viral infection - a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16 341–354. 10.1038/s41579-018-0003-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh P. E., Sin S. H., Ozgur S., Henry D. H., Menezes P., Griffith J., et al. (2013). Systemically circulating viral and tumor-derived microRNAs in KSHV-associated malignancies. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003484. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocucci E., Meldolesi J. (2015). Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 25 364–372. 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocucci E., Racchetti G., Meldolesi J. (2009). Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends Cell Biol. 19 43–51. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo M., Raposo G., Thery C. (2014). Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 30 255–289. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargan D. J., Patel A. H., Subak-Sharpe J. H. (1995). PREPs: herpes simplex virus type 1-specific particles produced by infected cells when viral DNA replication is blocked. J. Virol. 69 4924–4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargan D. J., Subak-Sharpe J. H. (1997). The effect of herpes simplex virus type 1 L-particles on virus entry, replication, and the infectivity of naked herpesvirus DNA. Virology 239 378–388. 10.1006/viro.1997.8893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David R. (2012). Viral infection: gift wrapped by the plasma membrane. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:732. 10.1038/nrmicro2905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paoli S. H., Tegegn T. Z., Elhelu O. K., Strader M. B., Patel M., Diduch L. L., et al. (2018). Dissecting the biochemical architecture and morphological release pathways of the human platelet extracellular vesiculome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75 3781–3801. 10.1007/s00018-018-2771-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Conde I., Shrimpton C. N., Thiagarajan P., Lopez J. A. (2005). Tissue-factor-bearing microvesicles arise from lipid rafts and fuse with activated platelets to initiate coagulation. Blood 106 1604–1611. 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps T., Kalamvoki M. (2018). Extracellular vesicles released by herpes simplex virus 1-infected cells block virus replication in recipient cells in a STING-dependent manner. J. Virol. 92:JVI.01102-18. 10.1128/JVI.01102-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Hensley L., Mcknight K. L., Hu F., Madden V., Ping L., et al. (2013). A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature 496 367–371. 10.1038/nature12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham J. A., Raab-Traub N. (2015). Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2 induces autophagy to promote abnormal acinus formation. J. Virol. 89 6940–6944. 10.1128/JVI.03371-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraile-Ramos A., Cepeda V., Elstak E., Van Der Sluijs P. (2010). Rab27a is required for human cytomegalovirus assembly. PLoS One 5:e15318. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraile-Ramos A., Pelchen-Matthews A., Risco C., Rejas M. T., Emery V. C., Hassan-Walker A. F., et al. (2007). The ESCRT machinery is not required for human cytomegalovirus envelopment. Cell Microbiol. 9 2955–2967. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhbeis C., Frohlich D., Kuo W. P., Amphornrat J., Thilemann S., Saab A. S., et al. (2013). Neurotransmitter-triggered transfer of exosomes mediates oligodendrocyte-neuron communication. PLoS Biol. 11:e1001604. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber P. P., Cabrini M., Jancic C., Paoletti L., Banchio C., Von Bilderling C., et al. (2015). Rab27a controls HIV-1 assembly by regulating plasma membrane levels of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Cell Biol. 209 435–452. 10.1083/jcb.201409082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould S. J., Booth A. M., Hildreth J. E. (2003). The Trojan exosome hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 10592–10597. 10.1073/pnas.1831413100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granato M., Santarelli R., Farina A., Gonnella R., Lotti L. V., Faggioni A., et al. (2014). Epstein-barr virus blocks the autophagic flux and appropriates the autophagic machinery to enhance viral replication. J. Virol. 88 12715–12726. 10.1128/JVI.02199-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose C., Buckingham E. M., Carpenter J. E., Kunkel J. P. (2016). Varicella-zoster virus infectious cycle: ER stress, autophagic flux, and amphisome-mediated trafficking. Pathogens 5:67. 10.3390/pathogens5040067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorgy B., Szabo T. G., Pasztoi M., Pal Z., Misjak P., Aradi B., et al. (2011). Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68 2667–2688. 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadigal S. R., Agelidis A. M., Karasneh G. A., Antoine T. E., Yakoub A. M., Ramani V. C., et al. (2015). Heparanase is a host enzyme required for herpes simplex virus-1 release from cells. Nat. Commun. 6:6985. 10.1038/ncomms7985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilingloh C. S., Krawczyk A. (2017). Role of L-particles during herpes simplex virus infection. Front. Microbiol. 8:2565 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilingloh C. S., Kummer M., Muhl-Zurbes P., Drassner C., Daniel C., Klewer M., et al. (2015). L particles transmit viral proteins from herpes simplex virus 1-infected mature dendritic cells to uninfected bystander cells, inducing CD83 downmodulation. J. Virol. 89 11046–11055. 10.1128/JVI.01517-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldwein E. E., Krummenacher C. (2008). Entry of herpesviruses into mammalian cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65 1653–1668. 10.1007/s00018-008-7570-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinshead M., Johns H. L., Sayers C. L., Gonzalez-Lopez C., Smith G. L., Elliott G. (2012). Endocytic tubules regulated by Rab GTPases 5 and 11 are used for envelopment of herpes simplex virus. EMBO J. 31 4204–4220. 10.1038/emboj.2012.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm M. M., Kaiser J., Schwab M. E. (2018). Extracellular vesicles: multimodal envoys in neural maintenance and repair. Trends Neurosci. 41 360–372. 10.1016/j.tins.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz R., Aierstuck S., Williams E. A., Melby B. (2010). Herpes simplex virus infection in a university health population: clinical manifestations, epidemiology, and implications. J. Am. Coll. Health 59 69–74. 10.1080/07448481.2010.483711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz S. N., Cheerathodi M. R., Nkosi D., York S. B., Meckes DG., Jr (2018). Tetraspanin CD63 bridges autophagic and endosomal processes to regulate exosomal secretion and intracellular signaling of epstein-barr virus LMP1. J. Virol. 92:e01969-17. 10.1128/JVI.01969-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo-Useros N., Naranjo-Gomez M., Erkizia I., Puertas M. C., Borras F. E., Blanco J., et al. (2010). HIV and mature dendritic cells: trojan exosomes riding the Trojan horse? PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000740. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson W. T., Giddings TH, Jr, Taylor M. P., Mulinyawe S., Rabinovitch M., Kopito R. R., et al. (2005). Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 3:e156. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Dupont N., Castillo E. F., Deretic V. (2013). Secretory versus degradative autophagy: unconventional secretion of inflammatory mediators. J. Innate. Immun. 5 471–479. 10.1159/000346707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamvoki M., Deschamps T. (2016). Extracellular vesicles during Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 infection: an inquire. Virol. J. 13:63. 10.1186/s12985-016-0518-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalamvoki M., Du T., Roizman B. (2014). Cells infected with herpes simplex virus 1 export to uninfected cells exosomes containing STING, viral mRNAs, and microRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 E4991–E4996. 10.1073/pnas.1419338111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra H., Drummen G. P., Mathivanan S. (2016). Focus on extracellular vesicles: introducing the next small big thing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:170. 10.3390/ijms17020170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasneh G. A., Shukla D. (2011). Herpes simplex virus infects most cell types in vitro: clues to its success. Virol. J. 8:481. 10.1186/1743-422X-8-481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian M. S. (2012). Dual role of autophagy in HIV-1 replication and pathogenesis. AIDS Res. Ther. 9:16. 10.1186/1742-6405-9-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein K. A., Jackson W. T. (2011). Picornavirus subversion of the autophagy pathway. Viruses 3 1549–1561. 10.3390/v3091549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouwaki T., Okamoto M., Tsukamoto H., Fukushima Y., Oshiumi H. (2017). Extracellular vesicles deliver host and virus rna and regulate innate immune response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:666. 10.3390/ijms18030666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J., Arras G., Colombo M., Jouve M., Morath J. P., Primdal-Bengtson B., et al. (2016). Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 E968–E977. 10.1073/pnas.1521230113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyei G. B., Dinkins C., Davis A. S., Roberts E., Singh S. B., Dong C., et al. (2009). Autophagy pathway intersects with HIV-1 biosynthesis and regulates viral yields in macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 186 255–268. 10.1083/jcb.200903070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai F. W., Lichty B. D., Bowdish D. M. (2015). Microvesicles: ubiquitous contributors to infection and immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 97 237–245. 10.1189/jlb.3RU0513-292RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J. K., Sam I. C., Chan Y. F. (2016). The autophagic machinery in enterovirus infection. Viruses 8:E32. 10.3390/v8020032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai R. C., Tan S. S., Yeo R. W., Choo A. B., Reiner A. T., Su Y., et al. (2016). MSC secretes at least 3 EV types each with a unique permutation of membrane lipid, protein and RNA. J. Extracell. Vesicles 5:29828. 10.3402/jev.v5.29828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. Y., Sugden B. (2008). The latent membrane protein 1 oncogene modifies B-cell physiology by regulating autophagy. Oncogene 27 2833–2842. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenassi M., Cagney G., Liao M., Vaupotic T., Bartholomeeusen K., Cheng Y., et al. (2010). HIV Nef is secreted in exosomes and triggers apoptosis in bystander CD4 + T cells. Traffic 11 110–122. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01006.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L. T., Dawson P. W., Richardson C. D. (2010). Viral interactions with macroautophagy: a double-edged sword. Virology 402 1–10. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhou Q., Xie Y., Zuo L., Zhu F., Lu J. (2017). Extracellular vesicles: novel vehicles in herpesvirus infection. Virol. Sin. 32 349–356. 10.1007/s12250-017-4073-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Leal R., Court F. A. (2016). Schwann cell exosomes mediate neuron-glia communication and enhance axonal regeneration. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 36 429–436. 10.1007/s10571-015-0314-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas S. L. N., Breakefield X. O., Weaver A. M. (2017). Extracellular vesicles: unique intercellular delivery vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 27 172–188. 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L., Wu J., Shen L., Yang J., Chen J., Xu H. (2016). Enterovirus 71 transmission by exosomes establishes a productive infection in human neuroblastoma cells. Virus Genes 52 189–194. 10.1007/s11262-016-1292-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masciopinto F., Giovani C., Campagnoli S., Galli-Stampino L., Colombatto P., Brunetto M., et al. (2004). Association of hepatitis C virus envelope proteins with exosomes. Eur. J. Immunol. 34 2834–2842. 10.1002/eji.200424887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLauchlan J., Rixon F. J. (1992). Characterization of enveloped tegument structures (L particles) produced by alphaherpesviruses: integrity of the tegument does not depend on the presence of capsid or envelope. J. Gen. Virol. 73( Pt 2), 269–276. 10.1099/0022-1317-73-2-269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara R. P., Costantini L. M., Myers T. A., Schouest B., Maness N. J., Griffith J. D., et al. (2018). Nef secretion into extracellular vesicles or exosomes is conserved across human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. mBio 9:e02344-17. 10.1128/mBio.02344-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckes D. G., Jr. (2015). Exosomal communication goes viral. J. Virol. 895200–5203. 10.1128/JVI.02470-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckes D. G., Jr., Raab-Traub N. (2011). Microvesicles and viral infection. J. Virol. 85 12844–12854. 10.1128/JVI.05853-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckes D. G., Jr., Gunawardena H. P., Dekroon R. M., Heaton P. R., Edwards R. H., Ozgur S., et al. (2013). Modulation of B-cell exosome proteins by gamma herpesvirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 E2925–E2933. 10.1073/pnas.1303906110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckes D. G., Jr., Shair K. H., Marquitz A. R., Kung C. P., Edwards R. H., Raab-Traub N. (2010). Human tumor virus utilizes exosomes for intercellular communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 20370–20375. 10.1073/pnas.1014194107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Saksena M., Denes C. E., Diefenbach R. J., Cunningham A. L. (2018). Infection and transport of herpes simplex virus type 1 in neurons: role of the cytoskeleton. Viruses 10:E92. 10.3390/v10020092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y., Koike M., Moriishi E., Kawabata A., Tang H., Oyaizu H., et al. (2008). Human herpesvirus-6 induces MVB formation, and virus egress occurs by an exosomal release pathway. Traffic 9 1728–1742. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00796.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munz C. (2017). The autophagic machinery in viral exocytosis. Front. Microbiol. 8:269 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan-Chari V., Clancy J. W., Sedgwick A., D’souza-Schorey C. (2010). Microvesicles: mediators of extracellular communication during cancer progression. J. Cell Sci. 123 1603–1611. 10.1242/jcs.064386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutsafi Y., Altan-Bonnet N. (2018). Enterovirus transmission by secretory autophagy. Viruses 10:139. 10.3390/v10030139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatogawa H., Suzuki K., Kamada Y., Ohsumi Y. (2009). Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10 458–467. 10.1038/nrm2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola A. V. (2016). Herpesvirus entry into host cells mediated by endosomal low pH. Traffic 17 965–975. 10.1111/tra.12408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkosi D., Howell L. A., Cheerathodi M. R., Hurwitz S. N., Tremblay D. C., Liu X., et al. (2018). Transmembrane domains mediate intra- and extracellular trafficking of epstein-barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J. Virol. 92:e00280-18. 10.1128/JVI.00280-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogues L., Benito-Martin A., Hergueta-Redondo M., Peinado H. (2018). The influence of tumour-derived extracellular vesicles on local and distal metastatic dissemination. Mol. Aspects Med. 60 15–26. 10.1016/j.mam.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte-’T Hoen E., Cremer T., Gallo R. C., Margolis L. B. (2016). Extracellular vesicles and viruses: Are they close relatives? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 9155–9161. 10.1073/pnas.1605146113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi Y. (2014). Historical landmarks of autophagy research. Cell. Res. 24 9–23. 10.1038/cr.2013.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvedahl A., Alexander D., Talloczy Z., Sun Q., Wei Y., Zhang W., et al. (2007). HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe 1 23–35. 10.1016/j.chom.2006.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski M., Carmo N. B., Krumeich S., Fanget I., Raposo G., Savina A., et al. (2010). Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 12 19–30; sup pp 1–13. 10.1038/ncb2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen D. J., Crump C. M., Graham S. C. (2015). Tegument assembly and secondary envelopment of alphaherpesviruses. Viruses 7 5084–5114. 10.3390/v7092861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegtel D. M., Cosmopoulos K., Thorley-Lawson D. A., Van Eijndhoven M. A., Hopmans E. S., Lindenberg J. L., et al. (2010). Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 6328–6333. 10.1073/pnas.0914843107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira E. A., daSilva L. L. (2016). HIV-1 Nef: taking control of protein trafficking. Traffic 17 976–996. 10.1111/tra.12412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponpuak M., Mandell M. A., Kimura T., Chauhan S., Cleyrat C., Deretic V. (2015). Secretory autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 35 106–116. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusic K. M., Pusic A. D., Kraig R. P. (2016). Environmental enrichment stimulates immune cell secretion of exosomes that promote CNS myelination and may regulate inflammation. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 36 313–325. 10.1007/s10571-015-0269-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzar Dominkus P., Ferdin J., Plemenitas A., Peterlin B. M., Lenassi M. (2017). Nef is secreted in exosomes from Nef.GFP-expressing and HIV-1-infected human astrocytes. J. Neurovirol. 23 713–724. 10.1007/s13365-017-0552-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab-Traub N., Dittmer D. P. (2017). Viral effects on the content and function of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15 559–572. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabouille C., Malhotra V., Nickel W. (2012). Diversity in unconventional protein secretion. J. Cell Sci. 125 5251–5255. 10.1242/jcs.103630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnaiah V., Thumann C., Fofana I., Habersetzer F., Pan Q., De Ruiter P. E., et al. (2013). Exosome-mediated transmission of hepatitis C virus between human hepatoma Huh7.5 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 13109–13113. 10.1073/pnas.1221899110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G., Stoorvogel W. (2013). Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 200 373–383. 10.1083/jcb.201211138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reske A., Pollara G., Krummenacher C., Chain B. M., Katz D. R. (2007). Understanding HSV-1 entry glycoproteins. Rev. Med. Virol. 17 205–215. 10.1002/rmv.531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins P. D., Dorronsoro A., Booker C. N. (2016). Regulation of chronic inflammatory and immune processes by extracellular vesicles. J. Clin. Invest. 126 1173–1180. 10.1172/JCI81131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. M., Tsueng G., Sin J., Mangale V., Rahawi S., Mcintyre L. L., et al. (2014). Coxsackievirus B exits the host cell in shed microvesicles displaying autophagosomal markers. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004045. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roizman B., Zhou G., Du T. (2011). Checkpoints in productive and latent infections with herpes simplex virus 1: conceptualization of the issues. J. Neurovirol. 17 512–517. 10.1007/s13365-011-0058-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghipour S., Mathias R. A. (2017). Herpesviruses hijack host exosomes for viral pathogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 67 91–100. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiana M., Ghosh S., Ho B. A., Rajasekaran V., Du W. L., Mutsafi Y., et al. (2018). Vesicle-cloaked virus clusters are optimal units for inter-organismal viral transmission. Cell Host Microbe 24:e208. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauflinger M., Fischer D., Schreiber A., Chevillotte M., Walther P., Mertens T., et al. (2011). The tegument protein UL71 of human cytomegalovirus is involved in late envelopment and affects multivesicular bodies. J. Virol. 85 3821–3832. 10.1128/JVI.01540-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorey J. S., Cheng Y., Singh P. P., Smith V. L. (2015). Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO Rep. 16 24–43. 10.15252/embr.201439363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S., Pendlebury S. A., Green C. (1984). Lipid organization in erythrocyte membrane microvesicles. Biochem. J. 224 285–290. 10.1042/bj2240285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick A. E., D’Souza-Schorey C. (2018). The biology of extracellular microvesicles. Traffic 19 319–327. 10.1111/tra.12558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Huang C. K., Yu H., Shen B., Zhang Y., Liang Y., et al. (2017). The role of exosomes in hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell Mol. Med. 21 986–992. 10.1111/jcmm.12950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. M., Reiner N. E. (2011). Exosomes and other microvesicles in infection biology: organelles with unanticipated phenotypes. Cell Microbiol. 13 1–9. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin J., Mangale V., Thienphrapa W., Gottlieb R. A., Feuer R. (2015). Recent progress in understanding coxsackievirus replication, dissemination, and pathogenesis. Virology 484 288–304. 10.1016/j.virol.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin J., Mcintyre L., Stotland A., Feuer R., Gottlieb R. A. (2017). Coxsackievirus B Escapes the Infected Cell in Ejected Mitophagosomes. J. Virol. 91:e01347-17. 10.1128/JVI.01347-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotland T., Sandvig K., Llorente A. (2017). Lipids in exosomes: current knowledge and the way forward. Prog. Lipid Res. 66 30–41. 10.1016/j.plipres.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szilagyi J. F., Cunningham C. (1991). Identification and characterization of a novel non-infectious herpes simplex virus-related particle. J. Gen. Virol. 72( Pt 3), 661–668. 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. P., Burgon T. B., Kirkegaard K., Jackson W. T. (2009). Role of microtubules in extracellular release of poliovirus. J. Virol. 83 6599–6609. 10.1128/JVI.01819-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. P., Kirkegaard K. (2008). Potential subversion of autophagosomal pathway by picornaviruses. Autophagy 4 286–289. 10.4161/auto.5377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temme S., Eis-Hubinger A. M., Mclellan A. D., Koch N. (2010). The herpes simplex virus-1 encoded glycoprotein B diverts HLA-DR into the exosome pathway. J. Immunol. 184 236–243. 10.4049/jimmunol.0902192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery C., Ostrowski M., Segura E. (2009). Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9 581–593. 10.1038/nri2567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pol E., Boing A. N., Harrison P., Sturk A., Nieuwland R. (2012). Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol. Rev. 64 676–705. 10.1124/pr.112.005983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen H. M., Masoumi N., Witwer K. W., Pegtel D. M. (2016). Extracellular vesicles exploit viral entry routes for cargo delivery. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80 369–386. 10.1128/MMBR.00063-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Niel G., D’angelo G., Raposo G. (2018). Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19 213–228. 10.1038/nrm.2017.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazirabadi G., Geiger T. R., Coffin W. F., III, Martin J. M. (2003). Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 (LMP-1) and lytic LMP-1 localization in plasma membrane-derived extracellular vesicles and intracellular virions. J. Gen. Virol. 84 1997–2008. 10.1099/vir.0.19156-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald A., Corey L. (2007). “Persistence in the population: epidemiology, transmission,” in Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis, eds Arvin A., Campadelli-Fiume G., Mocarski E., Moore P. S., Roizman B., Whitley R., et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., Liu C., Wang H., Wang L., Xiao F., Guo Z., et al. (2016). Surface phosphatidylserine is responsible for the internalization on microvesicles derived from hypoxia-induced human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into human endothelial cells. PLoS One 11:e0147360. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R. J. (2006). Herpes simplex encephalitis: adolescents and adults. Antiviral Res. 71 141–148. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willms E., Johansson H. J., Mager I., Lee Y., Blomberg K. E., Sadik M., et al. (2016). Cells release subpopulations of exosomes with distinct molecular and biological properties. Sci. Rep. 6:22519. 10.1038/srep22519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirawan E., Vanden Berghe T., Lippens S., Agostinis P., Vandenabeele P. (2012). Autophagy: for better or for worse. Cell Res. 22 43–61. 10.1038/cr.2011.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurdinger T., Gatson N. N., Balaj L., Kaur B., Breakefield X. O., Pegtel D. M. (2012). Extracellular vesicles and their convergence with viral pathways. Adv. Virol. 2012:767694. 10.1155/2012/767694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R., Rai A., Chen M., Suwakulsiri W., Greening D. W., Simpson R. J. (2018). Extracellular vesicles in cancer - implications for future improvements in cancer care. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15 617–638. 10.1038/s41571-018-0036-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakoub A. M., Shukla D. (2015). Autophagy stimulation abrogates herpes simplex virus-1 infection. Sci. Rep. 5:9730. 10.1038/srep09730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yañez-Mo M., Siljander P. R., Andreu Z., Zavec A. B., Borras F. E., Buzas E. I., et al. (2015). Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4:27066. 10.3402/jev.v4.27066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuana Y., Sturk A., Nieuwland R. (2013). Extracellular vesicles in physiological and pathological conditions. Blood Rev. 27 31–39. 10.1016/j.blre.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaborowski M. P., Balaj L., Breakefield X. O., Lai C. P. (2015). Extracellular vesicles: composition, biological relevance, and methods of study. Bioscience 65 783–797. 10.1093/biosci/biv084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Schekman R. (2013). Cell biology. Unconventional secretion, unconventional solutions. Science 340 559–561. 10.1126/science.1234740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]