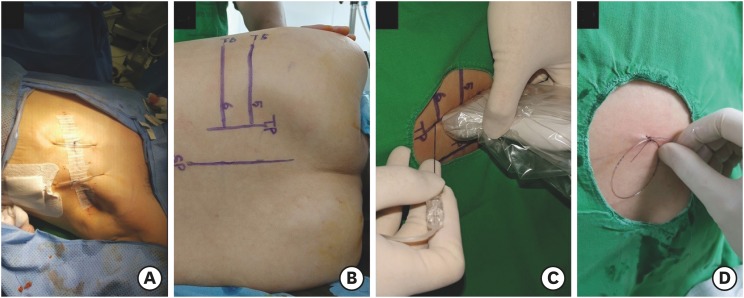

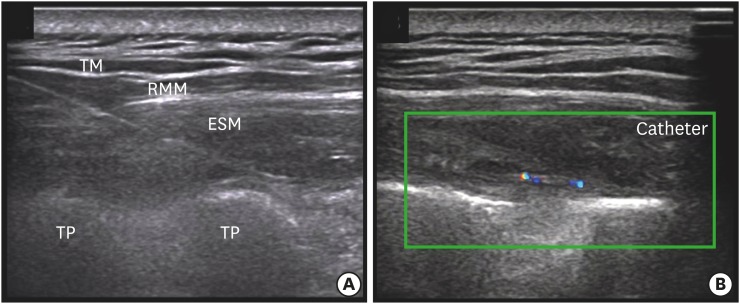

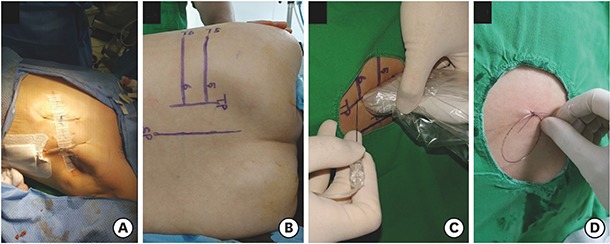

Three patients underwent total mastectomy with sentinel/axillary lymph node dissection. After the surgical procedure, ultrasound (US)-guided erector spinae plane block (ESPB) was performed. The fifth rib and transverse process (TP) was located using a 5–12 MHz linear probe; this was marked on the skin. At this level, the probe was moved from the lateral to the medial side transversely to identify any change in shape that traversed the rib and TP. Where the round shadow of the rib shifted to the rectangular shape of the TP, an 18-G Tuohy needle was inserted by using the in-plane technique (Fig. 1). After penetrating the erector spinae muscle, the needle was located in the fascial plane between the TP and erector spinae muscle. We confirmed that the fascial plane was well-separated by injecting 2 mL of saline. Then, 0.375% ropivacaine 30 mL with epinephrine (1:200,000) was injected, and the catheter was inserted 2 cm over the tip of the needle under real-time US guidance (Figs. 2 and 3). After the ESPB procedure, fentanyl 50 µg and ketorolac 30 mg were administered intravenously, and the patients were allowed to recover from general anesthesia. Postoperative pain was controlled by the acute pain service protocol of our hospital, oral acetaminophen 650 mg three times per day, combined with intravenous fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia (PCA; bolus 0.5 µg/kg without background infusion) and local anesthetic injection (0.375% ropivacaine 30 mL with epinephrine 1:200,000) via catheter every 12 hours for 3 days. Resting and dynamic (coughing, deep breathing) pain scores after surgery were assessed by using the visual analogue scale score.

Fig. 1. Surgical incision and technique of the ESPB. Total mastectomy with sentinel lymph node dissection was performed (A). The level of the T5 rib and TP was located using a counting-down approach from the first rib; this was marked on the skin (B). After placing a 5–12 MHz linear probe parallel to the vertebral axis, a needle was inserted, in a caudad-to-cephalad direction, toward the TP of T5 (C). Then, the catheter was inserted and secured by suture to the skin (D).

ESPB = erector spinae plane block, TP = transverse process.

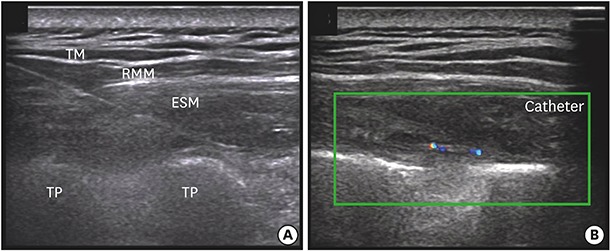

Fig. 2. Ultrasound-guided ESPB. A tuohy needle was inserted to contact the TP (A). After confirming proper position of the needle, a 19-G epidural catheter was inserted above 2 cm via real-time US guidance (B).

ESPB = erector spinae plane block, TM = trapezius muscle, RMM = rhomboid major muscle, ESM = erector spinae muscle, TP = transverse process, US = ultrasound.

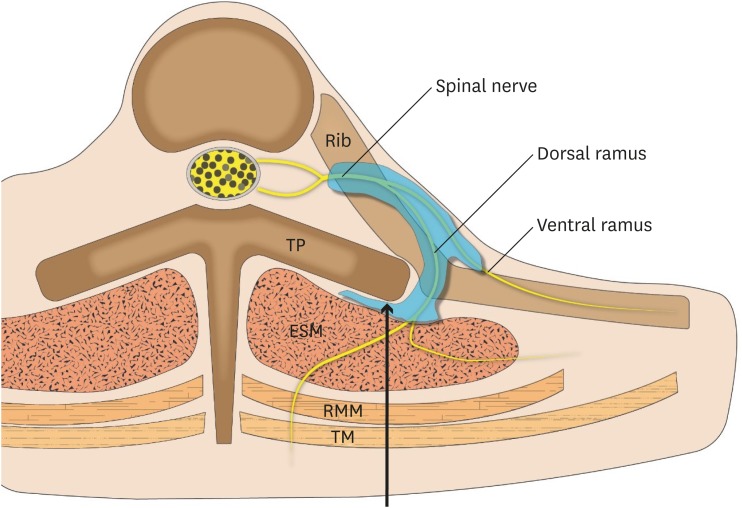

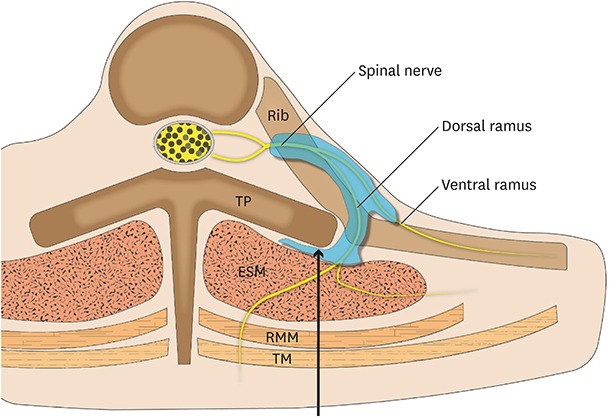

Fig. 3. Schematic diagram. Local anesthetic was injected between the erector spinae muscle and transverse process, and spread to the thoracic vertebral and intercostal space via bony gaps, such as the costotransverse foramen. Additionally, local anesthetic will pass through fenestrations in the costotransverse ligament, reaching the nerve root in the paravertebral space.

TP = transverse process, ESM = erector spinae muscle, RMM = rhomboid major muscle, TM = trapezius muscle.

The resting/dynamic pain scores were maintained below 2 points for 5 days postoperatively, and no additional rescue analgesics were administered during this period. The fentanyl consumption and demand were tracked using the PCA pump. The patients received their first demand dose of 24–34 µg of fentanyl between 12 hours and 15 hours after surgery, and the total number of bolus demands was two (case 1 and 2) and one (case 3) during the entire postoperative period.

Breast tissue is innervated by the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the T2–T6 intercostal nerves with variable involvement of the T1 and T7 intercostal nerves, as well as the supraclavicular branch of cervical plexus.1 Thus, thoracic epidural block and thoracic paravertebral nerve block are commonly used for analgesia after breast surgery, primarily by blocking these nerves. However, these techniques involve serious complications and multiple injections are needed.2,3,4,5

ESPB is a newly emerging truncal block that can cover a wide range, from T1–2 to T8–10,6 due to its wide cephalad-caudad spreading characteristic. It is an easy technique that involves injection of local anesthetic between the TP and erector spinae muscle. Moreover, ESPB can be performed regardless of wound dressing or surgical tissue disruption and is expected to cause less adjacent structural damage than other reginal anesthetic techiques.6,7,8,9

In conclusion, continuous ESPB provided effective analgesia after mastectomy with sentinel/axillary lymph node dissection. Therefore, we believe that ESPB can be a safe and effective option for analgesia after mastectomy.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Bang SU. Data curation: Kwon WJ, Sun WY. Writing - original draft: Kwon WJ, Bang SU, Sun WY. Writing - review & editing: Bang SU.

References

- 1.Woodworth GE, Ivie RM, Nelson SM, Walker CM, Maniker RB. Perioperative breast analgesia: a qualitative review of anatomy and regional techniques. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42(5):609–631. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawal N. Epidural technique for postoperative pain: gold standard no more? Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37(3):310–317. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31825735c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung JH, Gates S, Naidu BV, Wilson MJ, Gao Smith F. Paravertebral block versus thoracic epidural for patients undergoing thoracotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009121. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009121.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choe WJ, Kim JY, Yeo HJ, Kim JH, Lee SI, Kim KT, et al. Postpartum spinal subdural hematoma: irrelevant epidural blood patch: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016;69(2):189–192. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2016.69.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chae YJ, Han KR, Park HB, Kim C, Nam SG. Paraplegia following cervical epidural catheterization using loss of resistance technique with air: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016;69(1):66–70. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2016.69.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forero M, Adhikary SD, Lopez H, Tsui C, Chin KJ. The erector spinae plane block: a novel analgesic technique in thoracic neuropathic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41(5):621–627. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scimia P, Basso Ricci E, Droghetti A, Fusco P. The ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42(4):537. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos J, Peng P, Forero M. Long-term continuous erector spinae plane block for palliative pain control in a patient with pleural mesothelioma. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65(7):852–853. doi: 10.1007/s12630-018-1097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin KJ, Malhas L, Perlas A. The erector spinae plane block provides visceral abdominal analgesia in bariatric surgery: a report of 3 cases. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42(3):372–376. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]