Summary

Electroencephalography (EEG) is commonly used in epilepsy and neuroscience research to study brain activity. The principles of EEG recording such as signal acquisition, digitization, and conditioning share similarities between animal and clinical EEG systems. In contrast, preclinical EEG studies demonstrate more variability and diversity than clinical studies in the types and locations of EEG electrodes, methods of data analysis, and scoring of EEG patterns and associated behaviors. The TASK3 EEG working group of the International League Against Epilepsy/American Epilepsy Society (ILAE/AES) Joint Translational Task Force has developed a set of preclinical common data elements (CDEs) and case report forms (CRFs) for recording, analysis, and scoring of animal EEG studies. This companion document accompanies the first set of proposed preclinical EEG CRFs and is intended to clarify the CDEs included in these worksheets. We provide 7 CRF and accompanying CDE modules for use by the research community, covering video acquisition, electrode information, experimental scheduling, and scoring of EEG activity. For ease of use, all data elements and input ranges are defined in supporting Excel charts (Appendix S1).

Keywords: Epilepsy, Preclinical research, Rodent model, EEG, Common data elements, Case report form, Guidelines

Key Points.

The EEG working group of the TASK3 of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational Task Force developed common data elements (CDEs) and case report forms (CRFs) for animal EEG studies to promote standardization of data collection and data comparison/sharing among research groups

This article provides supporting documentation for the accompanying CRF and CDE documents

These CDE and CRF modules include the following: (1) video data acquisition, (2) electrode information, (3) experimental scheduling log, (4) EEG scoring methods, (5) EEG background activity scoring, (6) EEG epileptiform activity scoring, and (7) EEG seizure scoring

To address the heterogeneity in methods used for recording and analyzing preclinical video‐EEG recordings, we offer various CDEs and permissible values

Feedback and suggestions from the research community are invited to further improve these forms as well as to prioritize the included data elements to reflect

Electroencephalography (EEG) is commonly used in epilepsy and neuroscience research to study brain activity and the presence of epileptic abnormalities. Long‐term video‐EEG monitoring is the gold standard in studies aiming to record spontaneous seizures and document the presence and phenotype of epilepsy.1 The method for recording EEG from these small animals has not been standardized adequately yet.2 There are various EEG devices used for recording EEG in rodents, each with different capabilities with regard to number of electrodes it has capacity to record from, flexibility to generate different electrode montages, and methods to acquire, amplify, and filter the recorded signals. In preclinical studies, such diversity may make comparisons across studies more difficult. In addition, similar to clinical trials involving human subjects, there is a growing interest in adopting practices that may facilitate multicenter preclinical collaborative research or allow meta‐analyses of data through systematic reviews,3, 4 as well as facilitate the comparison of findings obtained in epilepsy animal models. Following up on the positive experience with the common data elements (CDEs) for clinical epilepsy studies that were introduced by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) in the United States,5, 6 the International League Against Epilepsy/American Epilepsy Society (ILAE/AES) Joint Translational Task Force (TF), in collaboration with NINDS launched a working group in 2014 to generate CDEs for preclinical epilepsy research.7, 8 This manuscript of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational TF introduces the preclinical CDEs organized into case report forms (CRFs) for preclinical studies utilizing electroencephalography (EEG), video‐EEG (vEEG), or electrophysiologic recordings in rodents. The recently published reports of the TASK1 groups of ILAE/AES Joint Translational TF outline some of the methodologic and reporting practices for the acquisition, interpretation, and analysis, including software‐based, of EEG performed in experimental control rodents.9, 10, 11, 12 In addition, readers may refer to additional considerations on reporting experimental methods and welfare of animals used for epilepsy research reported by Lidster et al. (2016).13 Here, we discuss how some of these principles can be incorporated in CDE and CRF documents to help guide the reader about which data and metadata would be helpful to be reported and catalogued in such forms. We realize that there is no consensus yet of the use of certain terms used in this first set of CDEs/CRFs and we invite readers to offer us feedback that will help optimize these documents. We hope that these forms will be the basis for the creation of software to facilitate and simplify the data logging by investigators in their studies.

In rodent studies, recordings of brain activity have often been done using subcutaneous, epidural, subdural, or depth electrodes. Traditionally, the term EEG refers to the collection of electrographic data using scalp electrodes, whereas the term electrocorticography refers to the more invasive procedures. However, the term EEG has often been used in the literature, more liberally, in reference to recordings done with more invasive procedures (e.g., using subdural or epidural electrodes). To simplify the forms, here we use the general term EEG for studies recording brain activity using surface, epidural/subdural, or depth recordings.

Structure of CDE Charts/CRF Modules for EEG Studies

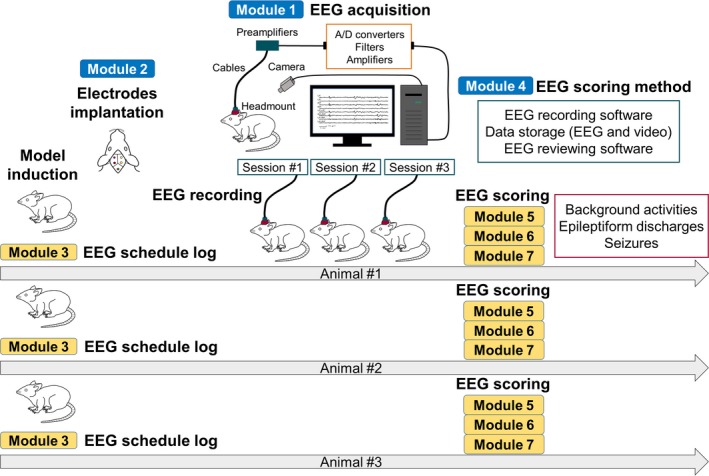

The first version of CDE charts and CRF modules on EEG recording and scoring for rodent models of epilepsy comprised a total of 7 modules (Fig. 1). Some of these modules can be filled once per animal (here indicated as “single entry”), whereas others are repetitive forms and need to be updated depending on the needs of the study design (indicated here as “recurrent”). For EEG recordings, we created 3 forms on EEG/video data acquisition (single entry), electrode information (single entry), and EEG recording schedule (modules 1–3, recurrent). For EEG scoring, we created 4 forms on scoring method, background activities, epileptiform discharges, and seizures (modules 4–7), which can be recurrent but used at epochs and events pre‐determined by the study design.

Figure 1.

Diagrams showing the application of each CRF module. Module 1, EEG/video data acquisition; module 2, electrodes; module 3, EEG recording schedule/log; module 4, EEG scoring method; module 5, EEG scoring ‐ General information and background activity; module 6, EEG scoring – epileptiform discharges; module 7, EEG scoring – seizures. Blue bars indicate the modules that are filled as single entries for each animal and could be used across animals that enter the same study design, simplifying data entry (e.g., modules 1, 2, 3‐a, 3‐b, 3‐c, 4). Yellow bars indicate modules that need to be filled for each animal either as single or recurrent entry, depending on the study design (e.g., modules 3‐d, 5, 6, 7). The order may be reversed between model induction and electrode implantation and the number of EEG recordings may be single session depending on the study protocol. The use of common templates to describe filled CRF modules that could be frequently recurring within the study may simplify data entry. For example, creating a pre‐filled module 1, 2, and 4 based on the study design may allow re‐use and re‐population of relevant data for multiple animals. Creation of a “typical EEG background” CRF template for controls may also allow re‐use in other animals and files that demonstrate the same background.

For other information except EEG recording and scoring, such as rodent species, animal characteristics, model type, physiologic monitoring, pharmacologic study design, and behavioral scoring other than seizures, the TASK3 group has created separate sets of CDEs and CRFs that investigators may use as needed based on the study design. For example, to describe the animal characteristics, one may use the core CDEs.14

Module 1: EEG/video data acquisition Relevant CRFs/CDEs file names (Appendix S1): CRF_1_EEG_data_acquisition.docx CDE_1_EEG_data_acquisition.xlsx

This module includes information on EEG recording hardware, software, and video data recording. If conditions of vEEG acquisition do not change through the study, this module can be filled once per animal (i.e., “single entry” module). The same CRF can be used for different animals within a given study that adopts the same design; therefore, if a common template is created, it could be used simplifying data entry across animals.

EEG hardware

In addition to the hardware brand and model name, information about the built‐in hardware filters is useful to include. Normally, a high‐pass filter and a low‐pass filter are built into the EEG device—these filter the signal prior to digitization. For details on the terms used in this guideline and CDE/CRF documents and the importance of these parameters, the reader is referred to the TASK1‐WG5 group of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational TF.9 In the CRF, location and input impedance of preamplifier, type of filter, discrimination ratio, filter settings (cutoff frequency, Hz), type of amplifier coupling, and sampling frequency of analog‐to‐digital (A/D) converter are reported. Depending on the device, filters may be described as the low‐pass (or high‐cut) filter and the high‐pass (or low‐cut) filter.9 In addition, on some devices, the high‐pass filter is described using the time constant (τ). In such cases, the formula 1/2πτ is used to calculate the cutoff frequency.15 The frequency of the AC power supply to power the device is included—in most cases, this is 50 or 60 Hz. The input impedance of the preamplifier should also be documented to compare with that of recording electrodes and to verify better signal‐to‐noise ratio.9, 16 If a stand‐alone preamplifier or headstage is used, the brand and model name of this equipment should also be included. Headmount or headset includes the electrodes and plugs, and in certain cases other sensors or transmitters that are implanted in the animal's skull to facilitate the recordings. In tethered recordings, headmount or headset are terms often used to describe the small prefabricated plugs on which electrode terminals are inserted and stabilized on the animal's skull. The terminals of the preamplifier can be plugged in the headmount to establish the connection required for the EEG recordings. For wireless recordings, the headmount also includes the transmitter.

EEG recording software

The brand and model name of the software for EEG and the type of files saved are included. The sampling frequency or rate is important, as it is an important piece of information if a frequency analysis is to be subsequently performed.9 Other recording parameters of the software may not be necessary for digital EEG acquisition depending on the hardware because signal amplification and filter settings are often defined on the hardware. They can be reconfigured offline during review of data depending on the type of data analysis planned. If older, analog systems are employed; the amplitude and filter settings used for the recording are very important to report.

Video recording

The use of synchronized video and EEG monitoring is helpful to investigate the relation between certain behaviors and the associated EEG patterns and determine whether a certain behavior is an electroclinical seizure or if an EEG pattern is artifactual (such as movement artifact) or brain derived.1, 17 Information regarding the display is color or gray scale, presence of infrared source, camera position, the number of animals recorded per camera; and the resolution, frame rate, file type, and other characteristics of the data are documented when video recording is performed.

This module also includes the connection method from animals to the EEG machine, meaning whether the connection was through cables (tethered), or radiotelemetry or capacitive telemetry was used or if a commutator (swivel) was in place.

Module 2: Electrodes Relevant CRFs/CDEs file names (Appendix S1): CRF_2_EEG_electrodes.docx CDE_2_EEG_electrodes.xlsx

This module includes information about the electrodes implanted in or attached to the animal, including the reference, ground, and recording electrodes as well as describes the material of these electrodes. This CRF is typically filled once for each animal, unless the animal is re‐implanted. The same CRF can be used for different animals within a given study that adopts the same design, and therefore, if a common template is created, it could be used to simplify data entry across animals.

With respect to the attachment or implantation of electrodes, a selection is made from the following options: epidural, subdural, intracerebral (deep brain), scalp, subcutaneous, or other. In addition, information about the electrode positions, that is, right or left, and the anatomic locations, is required. In particular, stereotaxic brain coordinates, based on the sagittal line, bregma, lambda, and depth from surface of either the skull or brain (one reference point can be selected), are valuable to report when electrodes are implanted on or inside the cranium. “Coordinates” are an important and universal method to identify site of electrode for research reporting, particularly for animal studies where there is no universal electrode placement system. However, it is more difficult to translate in statistics and is currently used to allow comparisons across studies. “Location” should be reported as a separate entity from coordinates, because it will be easier to utilize for grouping data. When researchers use the depth or array or surface grid electrodes including multiple contacts, the number of recording sites should be documented.

When attaching reference and ground electrodes to areas other than the head, their positions are useful to note. In EEG recordings where individual electrodes are used, references and ground are individual electrodes and (if commercial) have a manufacture and model number. In a multichannel electrode system, reference(s) is (are) incorporated in the array, and in such cases, the model of the array can be used.

Under conditions in which impedance measurement is possible, the impedance value of each electrode, especially that of the recording electrode, is highly useful. If electromyography and electrocardiography were recorded simultaneously, it is useful to add similar information as for the EEG recording electrodes.

The material and impedance of recording electrodes can greatly influence the quality of EEG data acquisition. The impedance between electrode and tissue may vary depending on the materials used for the electrode, and optimal values may depend on the purpose of the recordings. However, high impedance is one of the biggest factors that affects noise contamination. It is, therefore, preferable that the impedance value is kept as low as possible compared with the input impedance of the amplifier.16 In addition, it is desirable that there is no variation in the material and the impedance values of each electrode when using multiple recording electrodes, although there may be instances when this cannot be avoided, for example, when parallel recordings with screw or microelectrodes are undertaken.

Module 3: EEG experimental schedule log Relevant CRFs/CDEs file names (Appendix S1): CRF_3_EEG_schedule_log.docx CDE_3_EEG_schedule_log.xlsx

This module includes a section that is typically filled once per animal, briefly describing the model and general information on implantation and vEEG recording schedule (single entry), and a section that is used to log individual recording sessions (recurrent entry).

The schedule (experimental timeline) for animal model induction and EEG recording is reported in general terms. The name of the animal model to be induced such as “kainate‐induced status epilepticus model” or “electrical kindling model” is documented here. Model induction date and time, animal age at model induction day (expressed in postnatal [PN]] days) refer to the start date and time when induction of the model was done. When model induction lasts less than a day, for example, in status epilepticus models, this start date will be a single date when the model was induced. In models like the “electrical kindling,” for which induction occurs over a number of days, the first date (and time) when the first kindling stimulation started is logged.18 We did not include options for noninduced models (e.g., genetic models or inbred strains), since these are described in the core CRFs and CDEs that characterize the animal.14

Similarly, date and time of surgery and animal age in days are reported for the electrode implantation. Electrode implantation start date and time refer to the timepoints when electrode implantation procedure started and may not coincide with the model induction start date/time. Electrode implantation may precede the model induction (e.g., in models of status epilepticus) or follow the model induction (e.g., in traumatic brain injury models). To indicate the time period between model induction and electrode implantation, the elements “Model induction‐Electrode implantation date Interval” (EEGLogModIndImpDateInt) and “Model Induction‐Electrode implantation time Interval” (EEGLogModIndImpTimeInt) were included, which may be created automatically from the database, by subtracting the electrode implantation start Date/Time from the model induction start Date/Time. As a result, the input in this element can be positive (electrodes placed after model induction) or negative (electrodes placed before model induction).

When the animal is under anesthesia, the anesthetics used at the time of surgery and their routes of administration and doses or concentrations are logged.

The start and end dates of the EEG recording are documented and the age of the animal in postnatal days can be logged as a derivative of the date of birth (logged in the core CDEs). Intervals (in days or hours) are calculated using the following formulas of “model induction date – electrode implantation date,” “electrode implantation date – EEG recording start date,” and “model induction start date – EEG recording start date.”

The type of EEG experiment is selected. The choices include acute (typically minutes to few hours) or chronic (several days) EEG recording. The additional choices of single or multiple may indicate the situation when multiple sessions (including acute of acutely recorded sessions) may be done due to specific interventions (e.g., pre‐treatment vs post‐treatment, pre‐induction of seizures vs post‐induction of seizures, or morning vs afternoon session). EEG type may also be continuous or intermittent (recording interrupted by periods without monitoring). Selecting multiple choices is therefore possible (e.g., acute, multiple, intermittent, or chronic, multiple, continuous). The option for multiple or intermittent would prompt the utilization of the logging of the total number of sessions.

Continuous EEG recordings (i.e., ≥24 h) are commonly done for the analysis of sleep stages or seizure occurrence during circadian and ultradian wake‐sleep cycles in rodents12 that are of post‐weaning age. Before weaning, multiple intermittent sessions are often done when recordings are conducted using tethered recordings, particularly if video is co‐registered, to allow the pup to be fed by the dam. If the EEG recording was undertaken in multiple sessions under such situations19 there is the option to log information about each session and the number of sessions per day (frequency) in the following section.

Log of each session may include the start date and time of the EEG recording, animal age in days at the start of each EEG recording session, the end date and time, and animal age in days at the end of the EEG recording. If simultaneous video recording was performed, this information is also included.

If the EEG was recorded continuously without interruption, it may be considered as 1 session. For continuous long‐term (video) EEG recordings lasting more than 24 h, it is often more convenient to divide the recordings in multiple files, so as that 24 h of recording is counted as 1 session. This minimizes the file size of each (video) EEG recording session and facilitates the EEG scoring that occurs subsequently. In certain situations, long‐term EEG recording is not continuous but proceeds while skipping certain days (e.g., weekdays only, or on alternate days). Because the total duration of recorded EEG will not be the same as the interval between the first (start date) and last date of the EEG recording, the option to log the total day count of EEG recording per animal is offered “Total number of recording days count” (EEGLogRecTotalDaysCt). If EEG is continuous, with no interruptions, the element “EEG recording start to end date Interval” (EEGLogRecStartEndDateInt) is used instead. Logging the total duration of the EEG or vEEG recordings is important to report (priority set at moderate here) so as to compare the duration of monitoring between experimental and sham control groups as well as to help place the recorded frequency of seizures in the context of how intensive the EEG monitoring was.17

Video is useful to characterize behaviors and events associated with specific EEG patterns (brain derived or artifactual). The CDE module offers an option to log whether video recording was done [“Video recording Indicator,” (EEGLogVideoInd)], whether it was done according to the same schedule as EEG [“Duration of video recording Category,” (EEGLogVideoDurCat)], and—if a different schedule was followed—log the total duration of video monitoring [“Specify video recording Duration (days:hours:minutes),” (EEGLogVideoDur)].

Module 4: EEG scoring method Relevant CRFs/CDEs file names (Appendix S1): CRF_4_EEG_scoring_method.docx CDE_4_EEG_scoring_method.xlsx

The EEG scoring method is typically logged once per animal to indicate the methods of interpretation, analysis, and quantification of EEG patterns adopted in the study. EEG scoring can be broadly divided into the visual method and the software‐based method. Selection between these methods depends on which was used, and both can be selected if compatible with the planned data analyses. The same CRF can be used for different animals within a given study that adopts the same design, and therefore, if a common template is created, it could be used to simplify data entry across animals.

Logging whether the scoring was done blinded to experimental groups is important regardless of the scoring method.

Visual method

The montage used for interpretation, bipolar or referential montage, is selected. As digital EEG recording allows modification of the montage used, there is the option of selecting “both comparative” if both referential and bipolar montages are used. Notch filter information is also needed when digital EEG recording is used, as this method allows for modification of the filter settings at the time of interpretation. Regarding the montage, it is possible to create a separate table of supplementary information, and it is preferable to indicate the adjustments made to filter settings and amplitude gain for each channel.

Software‐based method

For the software‐based method, logging the software brand, name, and version or the algorithm name is requested. If an original analysis tool was created, this information can be separately explained along with information about the programming software and computer language used. The channel and filter settings used for analysis are also included as described earlier.

We have included the power spectrum and time frequency analysis, as well as spike and seizure detection as typical options for analysis, but other methods may be documented if applicable. In addition, the algorithms and window functions used in each analysis method (e.g., fast Fourier transform and wavelet analysis) are to be shown. For spike detection, parameter settings such as amplitude and kurtosis may also be required when the study results are reported, and these can be included in an uploaded file that describes these analyses parameters and tools. Because some of these analytical methods are novel and not necessarily widely used, at the present, they need to be entered using general terms in a text‐entry method. Due to the large variety of methods used in such specialized analyses, these details are not included here but can be the topic of future specialized research CRF modules.

Module 5: EEG scoring—background activity Relevant CRFs/CDEs file names (Appendix S1): CRF_5_ EEG_background_activity.docx CDE_5_ EEG_background_activity.xlsx

The scoring of background EEG activity can be done at pre‐determined timepoints or events, as planned in the study design. The CRF module can therefore be either single or recurrent entries, as decided by the investigator‐user.

General information on EEG record used for scoring

This section should be filled if any type of scoring was done on an EEG file, for example, for background (module 5), epileptiform discharges (module 6), or seizures (module 7), and only the pertinent sections used in the scoring (i.e., modules 5‐b, 6, 7).

The filename used for scoring is logged (EEG file name). EEG recording information used for EEG scoring including the recording date, animal age in days, session number, EEG file name and duration, and presence/absence of video recording are logged in the module. Information of drug(s) should be reported if anesthesia or other drug(s) is administrated during the recording. The filter settings and conditions of electrodes should be provided again, since they may be different at the acquisition versus scoring.

Background activity scoring

Background activity means the EEG background that is not associated with target events (e.g., baseline or interictal background if seizures are observed). Background activities and state‐dependent patterns similar to those observed in control populations in humans can also be observed in rodents, although some differences in maturation or pattern morphology can be seen.12, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 In addition, sleep EEG can be divided into the slow wave‐based non–rapid eye movement sleep stage (slow wave sleep or NREM) and the paradoxical sleep‐based rapid eye movement sleep stage (REM). Therefore, the structure of this module may be similar to that of a clinical EEG report. Background activity scoring can be carried out separately for wake and sleep states; however, the level of detail in sleep‐wake scoring may vary depending on the study goals. In this CRF, we maintained only a general description of sleep and awake patterns in the main CRF module. More detailed sleep scoring details can be entered in optional specialized module, since these are not done routinely across all studies. Although it is desirable to create one scoring module for each EEG session number that was assigned on module 4, this is optional and depends upon the specific analysis plans pre‐set by the investigator‐user in the study design. Terms and definitions/characteristics in EEG scoring are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Terms used in the EEG preclinical CDEs to describe background patterns

| Terms | Definitions/characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Background activity | The range of rhythms, activities, and patterns seen on EEG that characterize specific sleep‐wake or behavioral states, during periods without ictal patterns (e.g., seizures) | |

| Awake state EEG | Awake EEG is recorded during periods when the animal has eyes open and is either immobile (quiet wakefulness) or has purposeful locomotion or exploratory behavior. An alpha or theta rhythm may be seen depending on the behavioral state and age of the animal. Mixed frequency waveforms appear, typically faster than in NREM sleep, which may vary according to the age and electrode location and montage. Age differences exist | 12, 20, 21 |

| NREM sleep state EEG | NREM state EEG is characterized by increased delta slow‐wave background (maximally frontally), which often accompanies spindles (7–14 Hz) or K complexes. EMG usually has decreased signals. Age differences exist | 12, 20, 21, 22, 23, 41 |

| REM sleep state EEG | Corresponds to paradoxical sleep. It consists of low‐amplitude high‐frequency activities, which are similar to awake EEG, but the animal is asleep (eyes closed). There are also decreased EMG signals and occasional bursts of EMG activity (twitches). Age differences exist | 12, 20, 21, 24, 41 |

| Spindles | Regular rhythmic waves seen superimposed during NREM sleep state with frequency of 7‐14 Hz in rodents. Their appearance may depend on the age of animals | 22, 23, 41 |

| K‐complex | High amplitude slow wave, usually biphasic (negative‐positive) transients superimposed during NREM sleep | 38, 41 |

| Frequency range |

Delta, 1–3 Hz; Theta, 4–7 Hz; Alpha; 8–12 Hz, Beta, 13–30 Hz; Gamma, >30 Hz. This categorization of frequencies is based on the one used in human EEG studies and has been adopted in recent publications on rodent EEG recordings. However, this grouping does not necessarily correspond to names of specific physiologic rhythms recorded from certain regions or states in rodents |

12, 15, 41 |

| Slowing | Continuous or intermittent activity that is slower than the expected range of activities for the specific age/region/state of the animal. Slowing can also be generalized or focal, polymorphic, or rhythmic | 42 |

| Attenuation | Significant reduction in the background voltage amplitudes of the EEG. Criteria for “significant” may vary; reporting the definitions in each study is useful | |

| Suppression | Periods with lack of detectable EEG activities. Suppression can be continuous or intermittent | |

| Increased amplitude | High‐amplitude waves relative to the background activity Interpretation depends on the electrode montage and electrode location; definitions in a given study are valuable | |

| Excess fast activity | Excessive high‐frequency activities (beta or faster). The amplitude may be typically higher than the usual amplitude of these fast activities. Fast activities usually have lower amplitudes than the slower frequencies | 42 |

| Disorganization | Disruption of normal anteroposterior gradient of activities and absence of expected state‐related EEG patterns | |

| Sharp transients | Cortical sharp potentials, biphasic events with a duration of 250 msec in immature rodents (postnatal day 5–13) of uncertain significance | 43 |

| Sharp waves | Sharp waveforms 70–200 msec in duration that disrupt the background. These may or may not be epileptic in nature | |

| Slow activity transients (SATs) | Slow activity with a waveform lasting up to 7 s, that has high amplitude and delta (1–4 Hz) activities embedded. They may occur in neonatal rodents during all behavioral states | 43 |

| Discontinuity | Sudden alteration between background activities and periods of EEG suppression |

NREM, non–rapid eye movement sleep; REM, rapid eye movement sleep.

The principal frequency and amplitude of the background activity are reported. If frequencies of multiple bandwidths exist, each of them may be reported. We have used here the same nomenclature of frequency bands used also to characterize the frequencies in the human EEG studies (e.g., delta, theta, alpha, and beta), as agreed in the earlier reports of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational Task Force.11, 12 However, the frequency range of specific physiologic or pathologic rhythmic activities may differ among humans and rodents.11, 25, 26, 27, 28 In such cases, the investigators may log the observed frequency range in numerical values (in Hz) and check all the relevant frequency bands as appropriate.

If multiple electrodes were used for recording, the predominant distribution and the laterality of EEG activity should also be mentioned. During sleep, the presence of specific patterns, that is, sleep spindles and K‐complexes or sharp transients and slow activity transients for neonatal animals, indicating normal responses need to be mentioned. If researchers have not planned to assess these specific sleep patterns and background abnormalities in their study, the variable “not assessed” can be selected.

If nonepileptiform abnormal waveforms aberrant from the background activity, that is, abnormal slowing, attenuation, excessive fast activity, disorganization, discontinuity, burst‐suppression, and other variations are observed, those can be reported according to the module.

Module 6: EEG scoring—epileptiform discharges Relevant CRFs/CDEs file names (Appendix S1): CRF_6_EEG_epileptiform_events.docx CDE_6_EEG_epileptiform_events.xlsx

Scoring of epileptiform discharges can be done either once for the whole study (single entry) or at pre‐determined timepoints and files, as determined by the study design (recurrent entries).

General information on the EEG file used for scoring epileptiform discharges is the same as on module 5‐a for background scoring.

The terms and definitions/characteristics in EEG scoring of epileptiform discharges and seizures are shown in Table 2. In addition to the typical spikes/sharp waves and spike‐waves, the epileptiform discharges here include ‐high‐frequency oscillations (HFOs), which have drawn attention in recent years. HFOs have been classified into ripple (80‐200 Hz) and fast ripple (above 250 Hz).28, 29, 30 The complexity and the presence of rhythmicity, the occurrence, distribution, and symmetry across the 2 hemispheres, along with the bilateral synchronization or independence are documented for each abnormal wave. If the focus of the discharge localizes to a specific electrode or anatomic structure, this may also be specified. If there is periodicity and rhythmicity, the approximate frequency should also be reported. In animal models of epilepsy, epileptiform discharges can be found irrespective of wake or sleep state.31 It is desirable that the incidence be assessed for each stage, but quantitative assessment is optional. Reporting of the frequency of epileptiform discharges may vary depending on the animal model used and the study protocol. We provide an option to record the frequency either as events per unit time (numerical value) or as a categorical grouping similar to what was proposed in the Standardized Computer‐based Organized Reporting (SCORE) system used for human EEG, that is, once (once); uncommon (<1/5 min); occasional (1/5–1/min); frequent (1/min–1/10 s); abundant (>1/10 s).32 We acknowledge that the grouping of the frequencies of a discharge may differ across animal studies, since there are no uniform agreements on this issue for preclinical studies. We therefore suggest that this categorization is optional and, when done, the investigators are prompted to define their specific grouping parameters in the methods (i.e., methods of an article, or upload in the scoring methods file in module 4).

Table 2.

Terms used in the EEG preclinical CDEs to characterize epileptiform discharges and seizures

| Terms | Definitions/characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Spike | A wave with a sharp peak clearly standing out from the background, with a duration 70 msec or less | 15 |

| Sharp wave | A wave with a sharp peak clearly standing out from the background, with a duration 70–200 msec | 15 |

| Spike (or sharp) and wave complex |

A pattern in which a spike (or sharp wave) is immediately followed by a slow wave May be described as spike‐wave discharge or complex |

15 |

| High gamma/HFOs (ictal and interictal) |

EEG activity with frequencies usually greater than 80 Hz and several tens to hundreds of msec in duration interictally Ripples: 80‐200 Hz Fast ripples: over 250 Hz |

28, 29, 30 |

| Isolated | An event that is sporadic with no clear repetition, pattern, or rhythmicity | |

| Bursts | Sudden emergence of brief patterns (e.g., epileptiform) that clearly disrupt the background | |

| Bilaterally synchronous | An event that occurs at almost the same time on both hemispheres | 15 |

| Bilaterally independent | An event that occurs either at the left or the right hemisphere | 15 |

| Rhythmic | Repetitive waveforms at a predictable rhythmicity or periodicity | |

| Periodic | Rhythmic events that repeat at regular intervals | 15 |

| Pseudoperiodic | Repetitive events that appear to be periodic, but the intervals between the events are not exactly the same. May be described as “quasiperiodic” or “semiperiodic” | |

| Atypical | An event/pattern that resembles a classical epileptiform event/pattern, but differs in certain aspects of the morphology, symmetry, localization, or evolution | |

| Electroclinical seizure | A seizure pattern in the EEG that is associated with behavioral ictal correlates | |

| Electrographic seizure | A seizure pattern in the EEG that is not associated with any ictal behavioral correlates. The distinction between electrographic and electroclinical seizures also depends on the extent of electrode coverage and the ability to record from the regions where seizure begins or propagates to | |

| Behavioral seizure | A behavioral change that is thought to be epileptic but occurs without any EEG seizure correlate | |

| Cluster | Repetitive seizures that appear in the same day (e.g., more than 3 seizures/day). This definition may depend on the type of seizures or models. Different definitions have been used in the literature. The timeframe during which the seizure cluster appears and the presence and duration of “seizure‐free period” prior to and following the cluster are also elements that may need to be defined in each study | 44 |

| Infraslow | A very slow and sustained change in potential. May be described as DC‐shift, slow potential shift, or baseline shift | 45, 46 |

HFOs, high‐frequency oscillations.

Module 7: EEG scoringg—seizures Relevant CRFs/CDEs file names (Appendix S1): CRF_7_EEG_seizures.docx CDE_7_EEG_seizures.xlsx

Scoring for EEG patterns that resemble seizures is typically done for all the vEEG files that are collected for scoring, based on the study design (recurrent entries). If no seizures are observed, checking “No” under “Seizures captured?” may prompt skip the next sections. If “Yes” or “unclear” are checked, the following sections can be filled only for these specific events.

General information is the same as inn module 5a.

First, seizure type is classified into electroclinical, electrographic, and behavioral. The term “electrographic seizure” may encompass events with convincing seizure EEG correlate but behavior (when captured) is subtle or without any change from the baseline or unclear (e.g., when animal is not on full view). The term “behavioral seizure” can be used when EEG is not available or did not capture the event but the behavior of the animal was convincing for seizure (e.g., generalized tonic seizure).

The start time, end time, and duration of the seizure are measured separately for the EEG seizure and the behavioral seizure, if simultaneous video and EEG were done. Seizure clustering can be entered. A cluster is the occurrence of several seizures within a period of several hours, without meeting the criteria of status epilepticus (defined as one or more seizures lasting at least 30 minutes without recovery of baseline state between the ictal events). The definition of cluster is largely dependent on the criteria that have been preset for seizure onset and termination, which are often arbitrary in experimental studies and may vary between studies. It is valuable to clarify these criteria in the study reports, so that interpretation and comparisons of data can be made. Cluster presence and incidence also may be documented.

Behavioral findings

All the symptoms that were observed should be selected from the typical behavioral correlates listed on the module. Some of these behaviors are included in specific seizure behavioral scales. For example, the Racine scale has been proposed for limbic seizures in adult rodents,33 representing the progression of motor symptoms in the amygdala kindling model. Other scoring scales have been proposed for other age group or different models of seizures34, 35, 36 and the investigators are prompted to utilize the scoring scales relevant to the animal models they use. However, the behavioral scale is appropriate as a part of data analysis not data collection by CRF. Furthermore, there are numerous scales used that have been adapted or modified according to the model, age, or lab. If progression of those behaviors is assessed in accordance with the scales, the name and definition of the scale used should be provided (e.g., uploaded file) and the score should be indicated individually for each seizure event.

EEG findings

Ictal EEG patterns can be reported here for each seizure event (or for the characteristic seizure event(s), if so chosen by the experimental design, if seizures are very frequent) describing the onset, propagation/evolution, and postictal phases.37 The onset pattern is classified into rhythmic discharges, electrical attenuation, polymorphic slowing, and other patterns, which the investigator can fill in using free text form. Rhythmic discharges are further divided into slow waves, fast activity, and spikes/spike‐waves burst, and their frequencies and bandwidths are additionally reported. If there is a laterality or focality in the occurrence or distribution, this may be documented. If there is focality that corresponds to a specific electrode or anatomic structure, this may also be indicated. If the focality is unknown or diffuse, one of those should be selected. The propagation/evolution phase consists mainly of rhythmic discharges. Therefore, findings about these discharges may also be reported. For the postictal phase, findings such as recovery to background EEG or slowing, suppression/attenuation, or the occurrence of epileptiform activities are to be reported. Their spatial distribution (focal/unilateral or generalized/bilateral) is also to be documented.

Recovery and evolution

Finally, presence or absence of behavioral recovery should be observed. It should be determined whether the animal has returned to the normal state, transitioned to status epilepticus, progressed to mortality, or met euthanasia criteria. The time and duration also should be measured.

Selection and Prioritization of CDEs

The CDE charts and CRF modules include a considerable number of data and metadata and users may not be able to fill the entire forms. We have included prompts where certain sections can be filled once (single entry modules) or as recurrent entries, depending on the study, or skipped, if not planned by the specific study. Furthermore, short cuts can be created when these CRFs are used in a database, by generating templates describing the most common or characteristic set of entries (e.g., awake background in controls, acquisition settings for a specific study, etc.), which can then be selected to populate the relevant fields for several animals or appropriate files that fit these descriptions.

We view the CDEs both as a means of adopting a common language when reporting research that would facilitate across labs comparisons and input of data in big databases and as a system to facilitate adoption of best practices. Although a minimal set of CDEs would have been easier to use, we felt that offering additional CDEs, as options for use, would allow the users who decide to adopt them to collect more data on these which would be useful for future evaluation of their utility. In addition, by encouraging the collection of such additional data (which is not offered here as a requirement), the epilepsy community will be better informed in the future to decide on their importance for the rodent epilepsy studies, as has been done over the years for the human EEG.

These CDEs were proposed and assembled by the members of the TASK3‐preclinical EEG CDE working group based on discussions and prior publications on elements that are important to report in such studies or useful when conducting such experiments,9, 10, 11, 12 so that meaningful evaluation of study results and comparisons of data between different studies can be done. Depending on the nature and aims of a study, investigators may select to adopt certain of the proposed elements. To indicate which, in our opinion, elements are important to include, we have attempted to indicate the level of importance of data in the CDE chart as “high,” “moderate,” and “optional”; that is, which data should be minimally or preferably documented in CRF modules. It is suggested that elements that have high or moderate priority are the minimal essentials would be useful to be included in the standardized protocols9, 12 The CDEs proposed as “high” priority are shown in Table 3. We realize that community feedback will be essential in this prioritization and will be sought (see accompanying editorial in this special issue for the process). We offer this first set of CDEs/CRFs for open view and invite the investigators who use such recordings to offer their opinions, feedback, and justification for proposed changes, since we realize that both practical and scientific issues may be raised that could prompt us to reconsider the priority level of such elements.

Table 3.

List of proposed “high” prioritized CDEs for rodent EEG studies

|

Module 1 EEG data acquisition |

1‐a. EEG hardware

Brand and model |

|

1‐b. EEG software

Brand and model/version Sampling frequency Notch filter, high‐ and low‐pass filters, band pass filters Use of video recording | |

|

Module 2 Electrodes |

2‐a. Reference and ground electrodes |

|

2‐b. EEG recording electrodes

Number of electrodes Type and material Implantation mode (epidural, subdural, intracerebral, scalp, etc.) Location Coordinates (AP, ML, DV) | |

|

2‐c. Other recording electrodes (if used)

Recording type (EMG, EOG, ECG, etc.) Electrode type and material Implantation mode Location | |

| Module 3 |

3‐a. Animal model

Name of model Induction date, time, and age (if induction model) |

|

3‐b. Electrode implantation

Date, time, and age at surgery | |

|

3‐c. EEG recording

Start date, time, and age End date, time, and age Electrode implantation – Model induction interval Electrode implantation – EEG recording start interval Total EEG recording period duration Recording sessions (number, date, time, age) Recording type (acute, chronic, single or multiple sessions, etc.) | |

|

Module 4 EEG scoring method |

4‐a. Type of scoring (blinded/visual/software based)

Montage High‐ and low‐pass filters Notch filterSoftware brand, name, and version (if software based) Type of analysis (spectral/time frequency analysis, spike/seizure detection, etc.) Algorism |

|

Module 5 EEG scoring general information and background activity |

5‐a. General information

EEG scored period (start date, time, age; end date, time, age) High‐ and low‐pass filters Scoring with video Recording conditions (anesthetized, exposed to drug, etc.) |

|

5‐b. EEG scoring background activity

State EEG captured | |

|

Module 6 EEG scoring epileptiform discharges |

6. EEG‐scoring epileptiform discharges

Type (spikes/spike and wave discharges/pathologic HFOs) Frequency (occasional, moderate, abundant) Temporal distribution (sporadic, clustered, continuous)Anatomic distribution (focal/generalized, unilateral/ipsilateral/bilateral) |

|

Module 7 EEG scoring seizures |

7‐a. EEG scoring‐seizures

Number of seizures captured |

|

7‐b. Individual seizures/ictal‐like events log

Date, time, and age at seizure Type (electroclinical/electrographic/behavioral) | |

|

7‐c. Behavioral correlates

Ictal behaviors Seizure scale | |

|

7‐d. Ictal EEG pattern

Clarity of EEG onset, EEG propagation, and postictal EEG Focality/distribution (if multiple recording electrodes was used) EEG patterns (rhythmic discharges, electrical attenuations, etc.) | |

|

7‐e. Behavioral recovery/evolution

Recovery to baseline, transition to SE or other seizures |

AP, anterior‐posterior; DV, dorsal‐lateral; ECG, electrocardiography; EMG, electromyography; EOG, electrooculography; HFOs, high‐frequency oscillations; ML, medial‐lateral; SE, status epilepticus.

Practical Use of CRF Modules and Future Development

As a result, it may be necessary to input a large amount of data depending on the type of studies, but it should be practical for users and should not be laborious work for them (Fig. 1). Researchers only must fill the forms of module 1 (EEG/video data acquisition), 2 (electrodes), 3‐a, 3‐b, 3‐c, and 4 (EEG scoring method) once or few times per study (if indicated by the study design) unless the protocol is modified or updated. For example, in most cases, these CRFs for EEG acquisition and electrode placement will be done once and replicated through a specific study, so the investigators will not need to redo the whole form every time they do a surgery. Module 3‐d (EEG experimental schedule/log for individual sessions) is to be logged for each animal, since it contains individual time series data. In general, every study design includes a plan for EEG scoring.

For modules 5–7 related to EEG scoring of background activities, epileptiform discharges, and seizures, some parameters can be scored at preset timepoints; others can be scored in each session, as defined by the study section. For instance, if a study aims at scoring all the seizures captured, the module 7 (EEG scoring ‐ seizures) should be completed for each session that has been recorded. If seizures are too many, investigators may choose, if appropriate for their study design, to describe this detailed information for few characteristic seizure types. If no seizures were captured, however, only the general information (7‐a) should be completed. If a study investigates the EEG seizure patterns, the sections on EEG seizure patterns can be completed for each seizure by module 7.

However, there are certain situations that the study design may plan for less comprehensive scoring. For example, scoring of spike‐wave discharge bursts in absence seizure models can be very cumbersome due to their high frequency rate. In such cases, timepoints may be selected for scoring. The same situation also holds for some of the modules we offer (e.g., epileptiform discharges and background activities).

Even in that case, creation of CRF templates that describe entries that are encountered recurrently (e.g., EEG background in controls) may allow replicating these scored templates without necessarily filling each line of the CRF.

Ultimately, we would like to build a system that inputs data using software or online applications. This will greatly reduce the time and effort of researchers and enable users to quickly find out information in which they are interested. In database applications, this is easily solved by the use of templates that can be replicated and selected for use in all the animals for which these apply, to avoid making this laborious for the researcher. This may also enable researchers to customize CRFs for individual study protocols including post hoc and prospective multilaboratory collaborative study.

Furthermore, the current method of logging data by checkboxes will avoid the use of arbitrary terms (unless necessary) and computed‐based data registry will facilitate the utilization of these data for data analyses, since it will have standardized grouping methods.

Limitations and Challenges

EEG measurement and analysis methods in an animal model of epilepsy share a number of similarities with those in clinical practice. The principles of EEG recording, that is, signal acquisition, digitization, and conditioning, share similarities.9, 38 Data and metadata related to EEG measurement and analysis methods in animal models of epilepsy were created with reference to general knowledge of clinical EEG and the CDEs previously made public by the NINDS.6 On the other hand, there are also some differences between human and animal EEG studies. Notably, electrode properties are the most different elements between animal and clinical studies. The existing human scalp EEG CDEs take advantage of the fact that there is an accepted existing system for electrode placement of scalp EEG electrodes and terminology, which is not the case in the rodent video‐EEG studies. The electrode types and materials used in animal experiments, and their implantation positions, are different depending on the animal age, model, and research group. Because it is impractical to create a comprehensive form given this diversity, it is to be expected that there may be options that may not be included in this first edition of the CDE charts/CRF modules. We therefore include “other” options, where text entries may be written rather than pre‐defined values. We hope, however, that this first set of CDEs and CRFs will serve as a prototype for the first databases that will be created. We will also offer this as open access to attract feedback and comments for improvement.

Similarly, with respect to EEG scoring, definitions of EEG findings such as classifications of waveforms (e.g., bandwidth, spike wave, spike, and slow wave) can generally be standardized similarly to those of clinical EEG. In addition, seizure and epileptiform EEG manifestations in the experiments of animal models of epilepsy are defined by their similarity to such patterns found in humans, for example, absence epilepsy, tonic seizures, and spasms. However, there is less knowledge on the age‐, state‐, and species‐specificity of EEG patterns that are expected in experimental controls or animals with seizures or other pathologic conditions. There is also variability in these EEG findings across different seizure models. Our TASK1 working groups have published on some of these patterns seen in adult experimental control rodents,9, 10, 11, 12 but the efforts of distinguishing the age‐specificity, species/strain, and state‐ or disease‐relevance are currently in progress. Recently, there have been reports of experiments in which multi‐channel EEG recordings were conducted on rats.39, 40 Such studies can be useful in exploring the distribution or source of certain brain activities. In preclinical studies that aim to detect epilepsy and characterize the type of seizure activity and the EEG background, a minimally invasive electrode layout that provides a broader bilateral and rostrocaudal coverage has been helpful to identify seizures when their source is not certain as well as to document whether these are focal onset or generalized.

Unlike in clinical practice where there are accepted principles of EEG interpretation and reference EEG atlases are used, there have been no such textbooks or EEG atlases for animal models. This is currently in progress by the TASK1 group of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational TF, and we refer the reader to the first set of reports that pertain to EEG or in vitro electrophysiology animal studies in experimental controls,9, 12 which were used to create CDE charts/CRF modules for the background EEG in controls. The background of the EEG is not just relevant to the epilepsy researcher but also to the neuroscientist who utilizes this to characterize the phenotype of an animal model. It is important to incorporate possible and available CDEs that people who would be interested could utilize. By offering this possibility, more studies may be able to provide insight about the background of rodent EEG, facilitating therefore the optimization of a system for logging such background features and abnormalities. Of course, not all studies may need to use this, and selection and use of these CDEs and CRFs for EEG background scoring can be optional depending on the goals of a study.

The TASK1 group of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational Task Force is currently evaluating the abnormal and epileptiform patterns seen in rodent vEEG studied. In the absence of accepted standards for animal EEG interpretation, we created the CDEs based on knowledge of clinical EEG patterns, and the experience from rodent vEEGs of the involved investigators, adopting a descriptive approach. We anticipate that a future update of these CDEs will include the new terminology and classification of abnormal EEG patterns in animals, when it is formulated.

The critical reviews and helpful suggestions from researchers who have knowledge and experience on the subject is welcome by the authors as they would help resolve these limitations and problems and develop updated forms of CDE charts and CRF modules after this publication.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Tomonori Ono has received travel reimbursement from the ILAE, AES, and NINDS for meetings of this working group, and is on the editorial board of Epilepsia Open. He has no conflicts of interests with regard to this manuscript and CDEs/CRFs. Dr. Joost Wagenaar is an employee of Blackfynn, Inc., but has no conflict of interests with regard to this manuscript and pertinent CDEs/CRFs. Dr. Jason Moyer is currently an employee of UCB, Inc.; this position has no direct conflict of interest with the content of this manuscript. Dr. Lauren Harte‐Hargrove has received reimbursement from the AES for her role as project manager of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational TF and is currently assistant research director at Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE). She has no conflicts of interest relevant to this article. Dr. Aristea S. Galanopoulou is a co‐Editor‐in‐Chief of Epilepsia Open. She has received royalties for publications from Elsevier and travel reimbursement for meetings related to this work by ILAE, AES, and NINDS. She has received honorarium for participation in the scientific advisory board of Mallinckrodt, but she has no conflicts of interest in regard to this manuscript. None of the other authors has any conflicts to declare with regard to this manuscript. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. EEG CDE and CRF files. The preclinical EEG CDE and CRF modules linked to this article can be found and downloaded as a zip folder.

Acknowledgments

This report was written by experts selected by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the American Epilepsy Society (AES) and was approved for publication by the ILAE and the AES. Opinions expressed by the authors, however, do not necessarily represent the policy or position of the ILAE or the AES. We are also grateful to the AES, ILAE, and NIH/NINDS for partial sponsoring of the activities of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational Task Force. This report is a product of the EEG working group of the TASK3 of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational Task Force. We acknowledge the editorial assistance for CDE charts and CRF modules provided by Dr. Lauren C Harte‐Hargrove. T.O. receives research grant from the Japan Epilepsy Research Foundation. A.S.G. has received grant support by NINDS RO1 NS091170, U54 NS100064, the US Department of Defense (W81XWH‐13‐1‐0180), the Heffer Family and the Segal Family Foundations, and the Abbe Goldstein/Joshua Lurie and Laurie Marsh/Dan Levitz families.

Biography

Tomonori Ono, MD, PhD, is the director of the Epilepsy Center, National Nagasaki Medical Center, Japan.

References

- 1. Bertram EH. Monitoring for seizures in rodents In Pitkänen A, Schwartzkroin P, Moshé S. (Eds) Models of seizures and epilepsy. Burlington, San Diego, London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006:569–582. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galanopoulou AS, Simonato M, French JA, et al. Joint AES/ILAE translational workshop to optimize preclinical epilepsy research. Epilepsia 2013;54:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lapchak PA. Scientific rigor recommendations for optimizing the clinical applicability of translational research. J Neurol Neurophysiol 2012;3:3–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hooijmans CR, Ritskes‐Hoitinga M. Progress in using systematic reviews of animal studies to improve translational research. PLoS Med 2013;10:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Loring DW, Lowenstein DH, Barbaro NM, et al. Common data elements in epilepsy research: development and implementation of the NINDS epilepsy CDE project. Epilepsia 2011;52:1186–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NIH/NINDS . NINDS Common Data Elements: Epilepsy. Available at: https://commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/.

- 7. Galanopoulou AS. ILAE/AES Translational Research Task Force: An Update on the Joint ILAE‐AES Translational Initiatives to Optimize Epilepsy Research, 2017. Available at: https://www.aesnet.org/research/ilae/aes translational research task force.

- 8. Harte‐Hargrove LC, French JA, Pitkänen A, et al. Common data elements for preclinical epilepsy research: standards for data collection and reporting. A report of the TASK3 group of the AES/ILAE Translational Task Force of the ILAE. Epilepsia 2017;58(Suppl. 4):78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moyer J, Gnatkovsky V, Ono T, et al. Standards for data acquisition and software‐based analysis of in vivo electrophysiological brain recordings. Epilepsia 2017;58(Suppl. 4):53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raimondo JV, Heinemann U, de Curtis M, et al. Methodological standards for in vitro models of epilepsy and epileptic seizures. A report of the TASK1‐WG4 group of the AES/ILAE Translational Task Force of the ILAE. Epilepsia 2017;58(Suppl. 4):40–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hernan AE, Schevon CA, Worrell GA, et al. Methodological standards and functional correlates of depth in vivo electrophysiological recordings in control rodents. A TASK1‐WG3 report of the AES/ILAE Translational Task Force of the ILAE. Epilepsia 2017;58(Suppl. 4):28–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kadam S, D'Ambrosio R, Duveau V, et al. Methodological standards and interpretation of video‐EEG in adult control rodents. A TASK1‐WG1 report of the AES/ILAE Translational Task Force of the ILAE. Epilepsia 2017;58(Suppl. 4):10–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lidster K, Jefferys JG, Blümcke I, et al. Opportunities for improving animal welfare in rodent models of epilepsy and seizures. J Neurosci Methods 2016;260:2–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harte-Hargrove L, Galanopoulou A, French J, et al. Common data elements (CDEs) for preclinical epilepsy research: introduction to CDEs and description of core CDEs a TASK3 report of the ILAE/AES Joint Translational Task Force. Epilepsia Open 2018;3(S1):12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Libenson M. Practical approach to electroencephalography. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cooper R, Osselton JW, Shaw JC. EEG thechnology. London: Butterworth & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Galanopoulou AS, Kokaia M, Loeb JA, et al. Epilepsy therapy development: technical and methodologic issues in studies with animal models. Epilepsia 2013;54(Suppl. 4):13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McIntyre D. The kindling phenomenon In Pitkänen A, Schwartzkroin PA, Moshé SL. (Eds) Models of Seizures and Epilepsy. Burlington, San Diego, London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006:351–364. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scantlebury MH, Galanopoulou AS, Chudomelova L, et al. A model of symptomatic infantile spasms syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 2010;37:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horner RL, Liu X, Gill H, et al. Effects of sleep‐wake state on the genioglossus vs.diaphragm muscle response to CO(2) in rats. J Appl Physiol 2002;92:878–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benington JH, Kodali SK, Heller HC. Scoring transitions to REM sleep in rats based on the EEG phenomena of pre‐REM sleep: an improved analysis of sleep structure. Sleep 1994;17:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sitnikova E, Hramov AE, Grubov V, et al. Time‐frequency characteristics and dynamics of sleep spindles in WAG/Rij rats with absence epilepsy. Brain Res 2014;1543:290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sitnikova E, Hramov AE, Grubov V, et al. Age‐dependent increase of absence seizures and intrinsic frequency dynamics of sleep spindles in rats. Neurosci J 2014;2014:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shaw F. Is spontaneous high‐voltage rhythmic spike discharge in long evans rats an absence‐like seizure activity ? J Neurophysiol 2004;91:63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buzsáki G, Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science 2004;304:1926–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jing W, Wang Y, Fang G, et al. EEG bands of Wakeful Rest, slow‐wave and rapid‐eye‐movement sleep at different brain areas in rats. Front Comput Neurosci 2016;10:79 10.3389/fncom.2016.00079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Corsi‐Cabrera M, Pérez‐Garci E, Del Río‐Portilla Mc Y, et al. EEG bands during wakefulness, slow‐wave, and paradoxical sleep as a result of principal component analysis in the rat. Sleep 2001;24:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bragin A, Wilson CL, Almajano J, et al. High‐frequency oscillations after status epilepticus: epileptogenesis and seizure genesis. Epilepsia 2004;45:1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lévesque M, Bortel A, Gotman J, et al. Neurobiology of disease high‐frequency (80–500 Hz) oscillations and epileptogenesis in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis 2011;42:231–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Staba RJ. Normal and pathologic high‐frequency oscillations. Jasper's Basic Mech Epilepsies 2012;1:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matos G, Tsai R, Baldo M, et al. The sleep‐wake cycle in adult rats following pilocarpine‐induced temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2009;17:324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beniczky S, Aurlien H, Brøgger JC, et al. Standardized computer‐based organized reporting of EEG: SCORE – Second version. Clin Neurophysiol 2017;128:2334–2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation: II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1972;32:281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haas KZ, Sperber EF, Benenati B, et al. Idiosyncrasies of limbic kindling in developing rats In Corcoran M, Moshé S. (Eds) Kindling 5. New York: Plenum Press; 1998:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haas KZ, Sperber EF, Moshe SL. Kindling in developing animals: expression of severe seizures and enhanced development of bilateral foci. Dev Brain Res 1990;56:275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lüttjohann A, Fabene PF, van Luijtelaar G. A revised Racine's scale for PTZ‐induced seizures in rats. Physiol Behav 2009;98:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. de Curtis M, Avoli M. Initiation, propagation, and termination of partial (Focal) seizures. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015;5:a022368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Greenfield L. Approaching the EEG: an introduction to visual analysis In Greenfield LJ, Geyer JD, Carney PR. (Eds) Reading EEGs: a practical approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, A Wolters Kluwer Business; 2010:38–74. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee M, Kim D, Shin H, et al. High‐density EEG recordings of the freely moving mice using polyimide‐based microelectrode. J Vis Exp 2011;e2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bae J, Deshmukh A, Song Y, et al. Brain source imaging in preclinical rat models of focal epilepsy using high‐resolution EEG recordings. J Vis Exp 2015;e52700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brown RE, Basheer R, McKenna JT, et al. Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol Rev 2012;92:1087–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Geyer JD, Carney PR. Focal and generalized rhythm abnormalities In Greenfield LJ, Geyer JD, Carney PR. (Eds) Reading EEGs: a practical approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, A Wolters Kluwer Business; 2010:75–92. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seelke AMH, Blumberg MS. Developmental appearance and disappearance of cortical events and oscillations in infant rats. Brain Res 2010;1324:34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bajorat R, Wilde M, Sellmann T, et al. Seizure frequency in pilocarpine‐treated rats is independent of circadian rhythm. Epilepsia 2011;52:118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ikeda A, Taki W, Kunieda T, et al. Focal ictal direct current shifts in human epilepsy as studied by subdural and scalp recording. Brain 1999;122:827–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vanhatalo S, Holmes MD, Tallgren P, et al. Very slow EEG responses lateralize temporal lobe seizures: an evaluation of non‐invasive DC‐EEG. Neurology 2003;60:1098–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. EEG CDE and CRF files. The preclinical EEG CDE and CRF modules linked to this article can be found and downloaded as a zip folder.