Abstract

The aim of this review is to determine if the use of DHEA increases the likelihood of success in patients with POR. We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE using the terms "DHEA and diminished ovarian reserve", "DHEA and poor response", "DHEA and premature ovarian aging". A fixed effects model was used and Peto's method to get the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI 95%). For quantitative variables, Cohen's method was used to present the standardized mean differences (SMD) with their corresponding confidence intervals. Only five studied fulfilled the selection criteria. DHEA was administered in 25 mg doses, three times a day. In all studies, the authors corrected for the presence of confounding variables such as partner's age, infertility diagnosis and number of transferred embryos. The meta-analysis of the five selected studies assessed a total of 910 patients, who underwent IVF/ICSI, of which 413 had received DHEA. DHEA use was associated with a significant increase in pregnancy likelihood (OR 1.8, CI 95% 1.29 to 2.51, p=0.001). When analyzing the association between DHEA use and the likelihood of abortion, we found low heterogeneity between studies (I2=0.0%) and the use of DHEA to be associated to a significant reduction in the likelihood of abortion (OR 0.25, CI 0.07 to 0.95; p=0.045). Analysis of the association of DHEA with average oocyte retrieval showed high variability between studies (I2=98.6%), as well as no association between DHEA use and the number of oocytes retrieved (SMD -0.01, CI 95% -0.16 to 0.13; p<0.05).

Keywords: DHEA, diminished ovarian reserve, ICSI, IVF, poor ovarian response

INTRODUCTION

The management of patients with poor ovarian response (POR) with stimulation for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) still poses great challenges. Retrieval of few oocytes is associated with a lower number of embryos for transfer and a lower success rate (Keay et al., 1997). POR frequency is estimated at 5-18% for IVF/ICSI cycles, with a pregnancy rate as low as 2-4% (Yilmaz et al., 2013). POR is based on the presence of at least two of the following features: (i) older women, or any other POR risk factor; (ii) an earlier prior poor ovarian response; and (iii) an abnormal ovarian reserve test (low antral follicle count or low anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) (Ferraretti et al., 2011).

Different interventions have been tried on patients with POR, such as different stimulation protocols and adjuvant therapies to improve rates of ovarian response and pregnancy. Unfortunately, none of these regimes has been shown to be better over others (Pandian et al., 2010). The use of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) prior to stimulation is one of these interventions. DHEA is an endogenous steroid, originating in the reticular zone of the suprarenal cortex and ovarian theca cells. It is an essential prohormone in ovarian follicular steroidogenesis (Burger, 2002; Casson et al., 2000). Casson et al. (2000) described the beneficial effects of DHEA supplements in ovarian stimulation in patients with POR. There is still speculation regarding its mechanism of action. Oral administration of DHEA increases serum levels of IGF-I, which ought to have a positive effect on follicular development and oocyte quality.

The aim of this review is to determine if the use of DHEA increases the likelihood of success in patients undergoing IVF/ICSI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE using the terms "DHEA and diminished ovarian reserve", "DHEA and poor response", "DHEA and premature ovarian aging". Articles were first selected by title and abstract and then full text copies were obtained and scrutinized following our selection criteria. Two authors (JES and JC) revised the results from the search independently and retrieved those articles that fulfilled the selection criteria. In case of disagreement, a third author acted as referee. A reference list of relevant articles was also searched manually, looking for additional studies. We included studies comparing pregnancy rates in patients undergoing IVF/ICSI, in patients who received DHEA prior to ovarian stimulation, published between 2007 and 2017 either in English or in Spanish. We included studies that considered POR by the presence of at least two of the three following criteria: (a) patients older than 40 years of age; (b) antral follicle count lower than 5, or decreased AMH; (c) a deficient prior ovarian response. Secondary studies (i.e. systematic reviews, meta-analyses), and studies in which an additional drug was administered in conjunction with DHEA were excluded.

The collated data was transferred to a proforma form including: references, year of publication, inclusion criteria, type of study, DHEA doses, number of patients, number of clinical pregnancies, number of abortions and mean oocyte retrieval. The primary objective was the clinical pregnancy rate per initiated cycle. Clinical pregnancy was considered as the identification of at least one embryo displaying cardiac activity. Secondary objectives were average oocyte retrieval and abortion frequency.

We used STATA (STATA Corp. USA) for the meta-analysis. The heterogeneity between studies was tested using the Chi-squared test. For qualitative variables, a fixed effects model was used and Peto's method to get the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI 95%). For quantitative variables, Cohen's method was used to present the standardized mean differences (SMD) with their corresponding confidence intervals. The results were recorded in a forest plot.

RESULTS

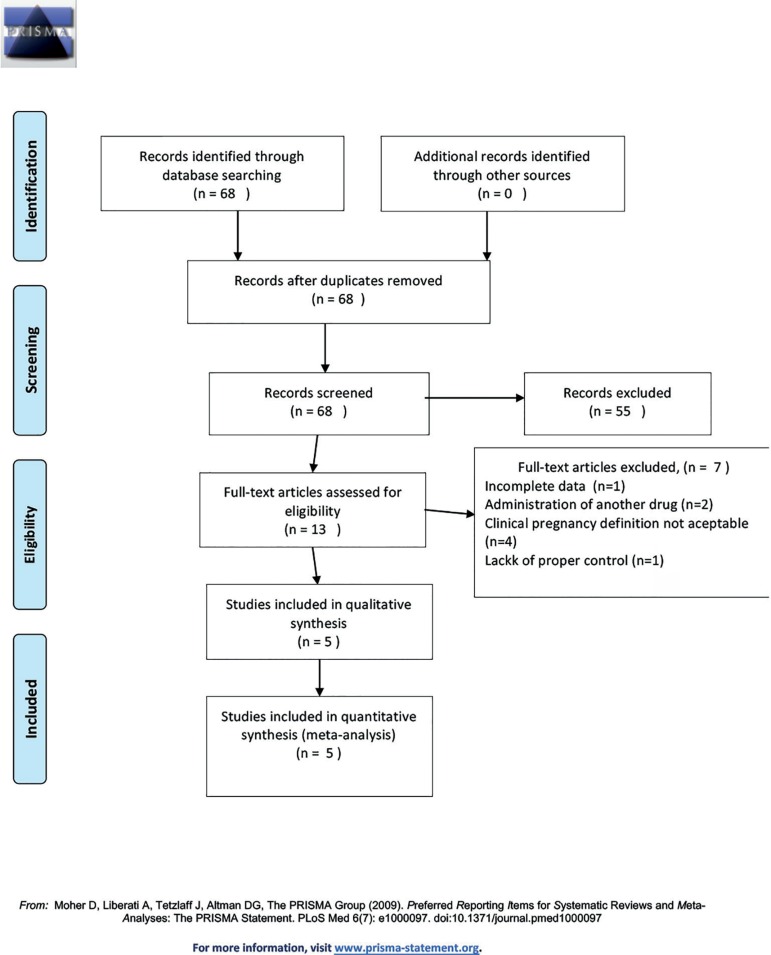

We initially identified 68 potentially relevant studies. After reading all the abstracts, 55 studies were excluded and full copies of the 13 remaining studies were retrieved. Only five studied fulfilled the selection criteria. Figure 1 shows the reasons for exclusion of studies. Studies included in this systematic review were published between 2007 and 2016 and their various study designs included: two retrospective studies (Barad et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2014), two randomized clinical trials (Wiser et al., 2010; Kotb et al., 2016), and one prospective cohort study (Vlahos et al., 2015). In all of these studies, DHEA was administered in 25 mg doses, three times a day. DHEA courses prior to IVF/ICSI cycles were: six weeks (Wiser et al., 2010); 12 weeks (Xu et al., 2014; Kotb et al., 2016; Vlahos et al., 2015); and 16 weeks (Barad & Gleicher, 2006). Four studies reported the use of DHEA to be associated with an increase in pregnancy rate (Xu et al., 2014; Wiser et al., 2010; Kotb et al., 2016; Barad & Gleicher, 2006) whereas one study found a decrease (Vlahos et al., 2015). In four studies, average oocyte retrieval was higher in groups receiving DHEA (Xu et al., 2014; Wiser et al., 2010; Kotb et al., 2016; Vlahos et al., 2015) whereas one study recorded a lower average (Barad & Gleicher, 2006) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included

| Study | Type of study | Outcome | Inclusion criteria | Exposure | Pregnancies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barad et al., 2007 | Case control | Mean number of oocytes recovery Implantation rate Clinical Pregnancy rate Abortion rate | FSH >12mIU/ml E2≥75pg/ml | 25mg tid for 4 months | DHEA group: 13/64 pregnancies Control group: 11/101 pregnancies |

| Wiser et al., 2010 | Randomized controlled trial | Mean number of oocytes recovery Clinical Pregnancy rate Abortion rate | Previous IVF cycle with more than 300IU rFSH/day Less than 5 embryos | 25mg tid for 6 weeks | DHEA group: 04/16 pregnancies Control group: 2/16 pregnancies |

| Xu et al., E22014 | Retrospective | Implantation rate Clinical Pregnancy rate | Two or more of following: ≥40years <4 oocytes recovered in previous cycle <5AFC | 25mg tid for 90 days | DHEA group: 57/189 pregnancies Control group :37/197 pregnancies |

| Vlahos et al., 2015 | Prospective | Clinical Pregnancy rate Delivery of a live born | Two of following: ≥40years <3 oocytes recovered in previous cycle E2 peak <500pg/ml | 25mg tid for 12 weeks | DHEA group: 1/48 pregnancies in Control group 8/113 pregnancies |

| Kotb et al., 2016 | Randomized controlled trial | Clinical Pregnancy rate | Bologna criteria | 25mg tid for 3 months | DHEA group 20/70 pregnancies Control group: 9/70 pregnancies |

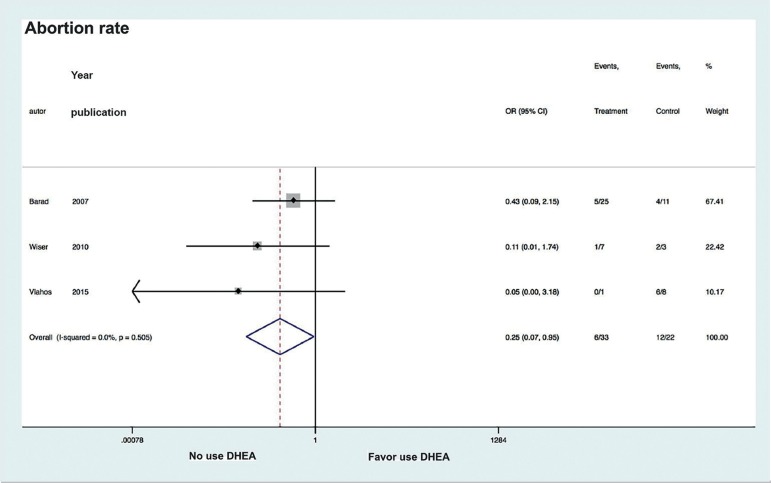

Only three studies recorded abortion rates and in all of them the rates were lower in those groups that had been given DHEA (Wiser et al., 2010; Vlahos et al., 2015; Barad & Gleicher, 2006). In all studies, the authors corrected for the presence of confounding variables such as partner's age, infertility diagnosis and number of transferred embryos (Xu et al., 2014; Wiser et al., 2010; Kotb et al., 2016; Vlahos et al., 2015; Barad & Gleiche, 2006).

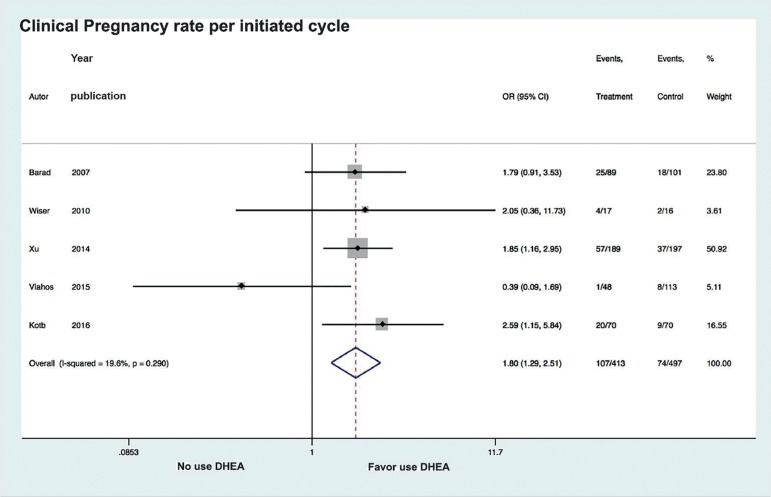

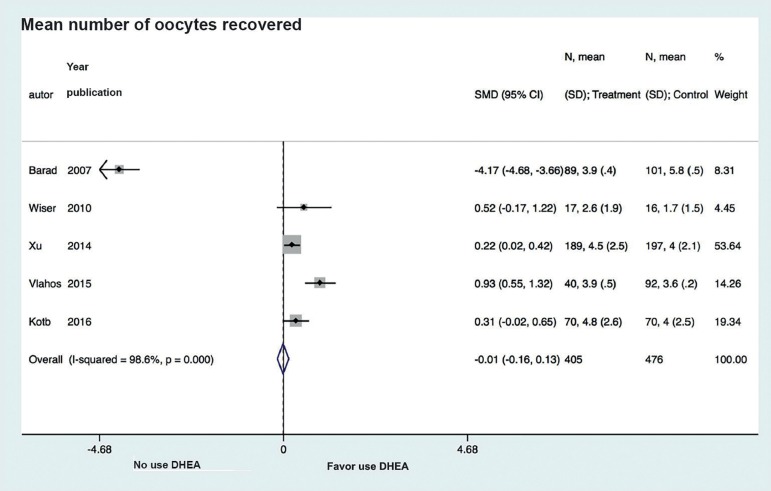

The meta-analysis of the five selected studies assessed a total of 910 patients who underwent IVF/ICSI, of which 413 had received DHEA. Analysis of the association between DHEA and likelihood of pregnancy revealed low heterogeneity between studies (I2=19.6%). DHEA use was associated with a significant increase in pregnancy likelihood (OR 1.8, CI 95% 1.29 to 2.51, p=0.001) (Figure 2). When analyzing the association between DHEA use and likelihood of abortion, we found low heterogeneity between studies (I2=0.0%), and the use of DHEA to be associated to a significant reduction in the likelihood of abortion (OR 0.25, CI 0.07 to 0.95; p=0.045) (Figure 3). Analysis of DHEA association with average oocyte retrieval showed high variability between studies (I2=98.6%) as well as no association between DHEA use and the number of oocytes retrieved (SMD -0.01, CI 95% -0.16 to 0.13; p<0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of comparison: DHEA versus control, outcome: Clinical Pregnancy rate per initiated cycle.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of comparison: DHEA versus control, outcome: Abortion rate.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison: DHEA versus control, outcome: Mean number of oocytes recovered.

DISCUSSION

This review evaluated the effects of DHEA treatment on IVF/ICSI outcomes in patients with POR. Our findings indicate that the use of DHEA is associated with a better pregnancy rate, a lower frequency of abortion, but without affecting average oocyte retrieval.

Our results differ from a previous meta-analysis carried out by Narkwichean et al., in which three studies, between 1980 and 2012, were analyzed and the authors found no association of treatment with DHEA with an improvement neither in the average oocyte retrieval, nor in the number of pregnancies (Narkwichean et al., 2013). Our study also did not find a difference in the average oocyte retrieval, but it did show an improvement in the clinical pregnancy rate. This implies that an improved clinical pregnancy rate might be due to an improvement in oocyte quality. Our findings of a lower rate of abortion in the DHEA groups further support this.

A potential limitation for this meta-analysis may be the fact that stimulation protocols differed between studies. However, there was no difference within each study in stimulation protocols between patients who received DHEA and those who did not. Another possible cause for confusion might be the difference in the number of weeks of DHEA administration, which varied between six and 14 weeks. However, the likelihood of pregnancy improved irrespective of the number of weeks DHEA was administered.

The mechanism of action whereby DHEA use might improve oocyte quality and or endometrium receptivity is yet to be elucidated, which is clinically translated into an improved pregnancy rate and a decrease in the abortion rate. In addition, it is yet to be determined whether there are differences between the different POR profiles (previous poor ovarian response age, or altered ovarian reserve tests) and DHEA use prior to ovarian stimulation.

We found that the use of DHEA prior to ovarian stimulation in women with POR is associated with an improvement in prognosis. Taking into account the outcomes of this review and given that DHEA is a well-tolerated drug; our recommendation is that DHEA should be included in the treatment of patients with POR.

REFERENCES

- Barad D, Gleicher N. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on oocyte and embryo yields, embryo grade and cell number in IVF. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2845–2849. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barad D, Brill H, Gleicher N. Update on the use of dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation among women with diminished ovarian function. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2007;24:629–634. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9178-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger HG. Androgen production in women. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S3–S5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson PR, Lindsay MS, Pisarska MD, Carson SA, Buster JE. Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation augments ovarian stimulation in poor responders: a case series. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:2129–2132. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.10.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraretti AP, La Marca A, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L. ESHRE working group on Poor Ovarian Response Definition. ESHRE consensus on the definition of 'poor response' to ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: the Bologna criteria. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1616–1624. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keay SD, Liversedge NH, Mathur RS, Jenkins JM. Assisted conception following poor ovarian response to gonadotrophin stimulation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:521–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotb MM, Hassan AM, AwadAllah AM. Does dehydroepiandrosterone improve pregnancy rate in women undergoing IVF/ICSI with expected poor ovarian response according to the Bologna criteria? A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;200:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkwichean A, Maalouf W, Campbell BK, Jayaprakasan K. Efficacy of dehydroepiandrosterone to improve ovarian response in women with diminished ovarian reserve: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11(44) doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandian Z, McTavish AR, Aucott L, Hamilton MP, Bhattacharya S. Interventions for 'poor responders' to controlled ovarian hyper stimulation (COH) in in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD004379–CD004379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004379.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahos N, Papalouka M, Triantafyllidou O, Vlachos A, Vakas P, Grimbizis G, Creatsas G, Zikopoulos K. Dehydroepiandrosterone administration before IVF in poor responders: a prospective cohort study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;30:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser A, Gonen O, Ghetler Y, Shavit T, Berkovitz A, Shulman A. Addition of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) for poor-responder patients before and during IVF treatment improves the pregnancy rate: a randomized prospective study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2496–2500. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz N, Uygur D, Inal H, Gorkem U, Cicek N, Mollamahmutoglu L. Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation improves predictive markers for diminished ovarian reserve: serum AMH, inhibin B and antral follicle count. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169:257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Li Z, Yue J, Jin L, Li Y, Ai J, Zhang H, Zhu G. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone administration in patients with poor ovarian response according to the Bologna criteria. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]