Abstract

Background:

Human papilloma virus (HPV) infection is the major etiologic agent of cervical carcinoma. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of HPV infection and genotype distribution in cervical swabs from 2,234 Turkish and 357 Albanian women with similar lifestyles from two different countries.

Materials and Methods:

HPV detection and typing were performed by type specific multiplex fluorescent PCR and fragments were directly genotyped by high resolution fluorescence capillary electrophoresis.

Results:

The most common type was HPV 16 and the second one was HPV 6 for both country. The third common type was 39 and 18 for Turkish and Albanian women, respectively.

Conclusions:

When we compare our results with other studies, there are differences between the frequency and order of the HPV genotypes detected at the second and subsequent frequencies. This may due to differences in the quality and type of samples analyzed, as well as the HPV detection methods.

Keywords: Albania, HPV prevalence, Turkey

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women worldwide.[1] Over 90% of women with cervical cancer are human papilloma virus (HPV) positive.[2] Persistence of the HPV infection as well as viral DNA insertion in epithelial cells are the main factors leading to high-grade dysplasia with the potential of progression to carcinoma in situ and invasive cancer.[3] HPVs are small viruses composed by a nonenveloped capsid and a circular double stranded DNA genome with sizes close to 8 kb. Their genome is composed of three domains: a noncoding upstream regulatory region of approximately 1 kb, an early coding region (E genes), and a late coding region (L genes). Different epidemiological studies reveal that HPV prevalence depends on age and sexual practices and show major differences across geographic areas. HPV prevalence has been described to be higher in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa and lower in Asia and Europe.[4,5,6,7,8,9] Although more than 100 HPV types have been identified and approximately 40 of them are known to infect humans, only about 15 of them cause cervical cancer and its precursor lesions. HPV types 16 and 18 are responsible for about 70% of all cervical cancer cases and most of the female genital warts are caused by HPV types 6 and 11 in many developed countries. Fifteen mucosal HR-HPVs (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, 82) are reported to be associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and cervical cancer. HPV 16 is the most common HPV type detected in squamous cervical cancer (SCC, 55%), followed by HPV 18 (12.8%), and together these two types cause around 70% or more of SCC irrespective of geographical locale. The next most frequently detected HPVs worldwide are HPV 31, 33, 45, which contribution does not exceed 4% each.[10]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our study included 2,234 Turkish and 357 Albanian cervical specimens with low- or high-grade cervical intraepithelial lesions (SILs) from Obstetrics and Gynecology clinics of the 20 different hospitals. Age ranges were between 21 and 66 (mean age 35.4) and 19 and 67 (mean age 32.2) in Turkish and Albanian group, respectively. Each participant gave written-informed consent before she was enrolled and the study was approved by the institution. DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (Magnesia Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction kit, Anatolia, Istanbul, Turkey). Extracted DNA was amplified using a multiplex F-HPV PCR with a set of 15 fluorochrome-labeled primers recognizing HPV types within the E6 and E7 regions of the HPV genome. The F-HPV amplification was performed in a final PCR volume of 25 μL containing 20 μL of reaction mixture and 5 μL of extracted DNA for 35 repeat cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 64°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Products were analyzed using capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 3500×l genetic analyzer and GeneMapper 5.0 Software (Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

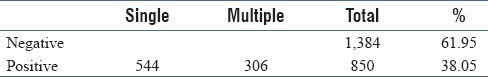

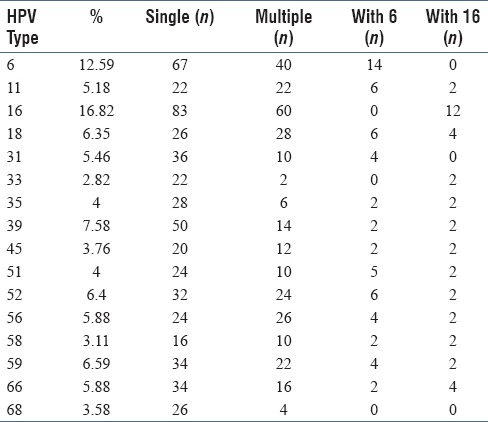

HPV DNA was positive in 850 of 2,234 (38.05%) Turkish cervical samples. Although 544 samples (64%) a single HPV type was genotyped, more than one HPV type was identified in 306 samples (36%) as shown in Table 1. HPV 16 as the most frequent type accounting for 143 of 850 typed cases (16.82%). HPV 6 was the second most common type being detected in 107 of 850 typed cases (12.59%). HPV 39 ranked third with 64 of 850 cases (7.58%). HPV 59 was the fourth with 54 of 850 cases (6.59%), HPV 52 and 18 were detected in 56 and 54 cases, respectively (6.4; 6.35%), and were followed by HPV 56 and 66 (50 cases, 5.88%). These eight types constitute about 70% of the total.

Table 1a.

HPV positivity rate and prevalence of HPV types among 2,234 cases in Turkey. Positivity rate

Table 1b.

HPV positivity rate and prevalence of HPV types among 2,234 cases in Turkey. Prevalence of HPV types

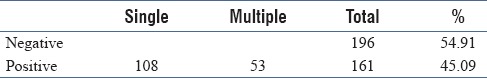

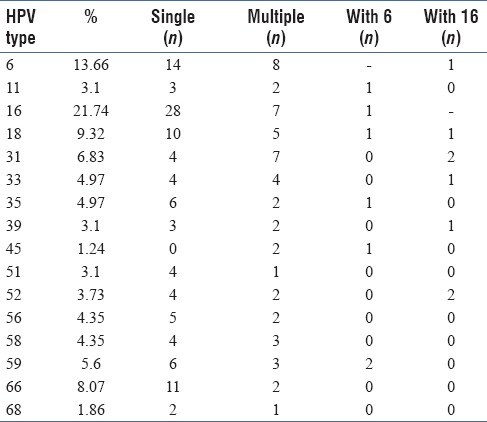

In Albanian group, HPV DNA was positive in 161 of 357 (45.09%). Single HPV type was calculated 67.08% (108 cases), multiple HPV type was calculated 32.92% (58 cases) as shown in Table 2. HPV 16 as the most frequent type accounting for 35 of 161 typed cases (21.74%). HPV 6 was the second most common type being detected in 22 of 161 typed cases (13.66%). HPV 18 is the third with 15 of 161 typed cases (9.32%).

Table 2a.

HPV positivity rate and prevalence of HPV types among 357 cases in Albania

Table 2b.

HPV positivity rate and prevalence of HPV types among 357 cases in Albania

DISCUSSION

In Turkey, HPV prevalence has been reported between 2.0% and 46.0% in some regional studies.[11,12,13] However, these studies had a limitation that they were conducted in a single center. With this study HPV type distribution, and the relationship between HPV positivity were studied from the cervical smear samples of women from 20 hospitals in different regions of Turkey. In Albania, HPV prevalence has been reported 15.1–43.9%.[14,15] In a study with a very large numbers of Turkish patients, 25% of women were found to be HPV positive.[16] This ratio is not compatible with our study (38.05%). This was possible due to the use of a multiplex PCR-based method that showed a high sensitivity and specificity. This HPV detection assay is also very sensitive to detect multiple infections as it is based on the use of type-specific primers, rather than consensus/degenerated primers. In general, the rate of HPV positivity is low in studies using sequencing after PCR with degenerate primers as a method. In the presence of multiple infections, DNA sequencing is unable to resolve.[17] There are some studies supporting this result and also compatible with the results of our study from Turkey.[18,19,20] In a microarray-based study, 44.7% of all patients were HPV positive.[18] In another study with a linear array method, HPV positivity was calculated 46.3%.[19] Duran AC et al. reported that, in 100 of 261 genital samples, HPV DNA were positive using real time PCR method.[20] This ratio, which is 38.3%, is almost the same as our result (38.05%).

Filipi et al. reported 15.1% of the cohort were found to be HPV positive.[14] This rate is lower than both as a result of our study and also another HPV study from Albania.[15] We think that the reason of this difference is due to using of the sequencing method, as discussed above. In a recent study from Albania, HPV prevalence has been reported 43.9% but there is no any molecular methods in this study to identify of the HPV type.[15]

CONCLUSION

In summary, our findings show that the most common type was HPV 16, which is similar to data from lots of other studies. On the other hand, there are differences between the frequency and order of the HPV genotypes detected at the second and subsequent frequencies. This may be explained by differences in the quality and type of samples analyzed, as well as the HPV detection methods.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bosch X, Munoz N. The viral etiology of cervical cancer. Virus Res. 2002;89:183–90. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luhn P, Walker J, Schiffman M, Zuna RE, Dunn ST, Gold MA, et al. The role of co-factors in the progression from human papillomavirus infection to cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreccio C, Prado RB, Luzoro AV, Ampuero SL, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, et al. Population-based prevalence and age distribution of human papillomavirus among women in Santiago, Chile. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13:2271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molano M, Posso H, Weiderpass E, van den Brule AJ, Ronderos M, Franceschi S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of HPV infection among Colombian women with normal cytology. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:324–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin HR, Franceschi S, Vaccarella S, Roh JW, Ju YH, Oh JK, et al. Prevalence and determinants of genital infection with papillomavirus, in female and male university students in Busan, South Korea. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:468–76. doi: 10.1086/421279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas JO, Herrero R, Omigbodun AA, Ojemakinde K, Ajayi IO, Fawole A, et al. Prevalence of papillomavirus infection in women in Ibadan, Nigeria: A population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:638–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Speich N, Schmitt C, Bollmann R, Bollmann M. Human papillomavirus (HPV) study of 2916 cytological samples by PCR and DNA sequencing: Genotype spectrum of patients from the West German area. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:125–8. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velazquez-Marquez N, Paredes-Telo MA, Perez-Terron H, Santos-Lopez G, Reyes-Leyva J, Vallejo-Ruiz V. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes in women from a rural region of Puebla, Mexico. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:690–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Sanjosé S, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Clifford G, Bruni L, Muñoz N, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: A meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:453–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozcelik B, Serin IS, Gokahmetoglu S, Basbug M, Erez R. Human papillomavirus frequency of women at low risk of developing cervical cancer: A preliminary study from a Turkish university hospital. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003;24:157–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inal MM, Kose S, Yildirim Y, Ozdemir Y, Toz E, Ertopcu K, et al. The relationship between human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in Turkish women. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:1266–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dursun P, Senger SS, Arslan H, Kuscu E, Ayhan A. Human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence and types among Turkish women at a gynecology outpatient unit. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filipi K, Tedeschini A, Paolini F, Celicu S, Morici S, Kota M, et al. Genital human papillomavirus infection and genotype prevalence among Albanian women: A cross-sectional study. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1192–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kone ES, Balili AD, Paparisto PD, Ceka XR, Petrela ED. Vaginal Infections of Albanian women Infected with HPV and their impact in intraepithelial cervical lesions evidenced by Pap test. J Cytol. 2017;34:16–21. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.197592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dursun P, Ayhan A, Mutlu L, Caglar M, Haberal A, Gungor T, et al. HPV types in Turkey: multicenter hospital based evaluation of 6388 patients in Turkish gynecologic oncology group centers. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2013;29:210–6. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2013.01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giuliani L, Coletti A, Syrjänen K, Favalli C, Ciotti M. Comparison of DNA sequencing and Roche Linear array in human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3939–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cilingir IU, Bengisu E, Agacfidan A, Koksal MO, Topuz S, Berkman S, et al. Microarray detection of human papilloma virus genotypes among Turkish women with abnormal cytology at a colposcopy unit. J Turk Gynecol Assoc. 2013;14:23–7. doi: 10.5152/jtgga.2013.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colakoglu S, Bolat FA, Coban G. Human papilloma virus (HPV) prevalence and genotype distribution. J Clin Anal Med. 2017;8:109–13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duran AC, Erdin BN, Sayıner AA. Determination of human papilloma viruses DNA and genotypes in genital samples with PCR. J Clin Anal Med. 2017;8:302–6. [Google Scholar]