Abstract

Epoxy PUFAs are endogenous cytochrome P450 (P450) metabolites of dietary PUFAs. Although these metabolites exert numerous biological effects, attempts to study their complex biology have been hampered by difficulty in obtaining the epoxides as pure regioisomers and enantiomers. To remedy this, we synthesized 19,20- and 16,17-epoxydocosapentaenoic acids (EDPs) (the two most abundant EDPs in vivo) by epoxidation of DHA with WT and the mutant (F87V) P450 enzyme BM3 from Bacillus megaterium. WT epoxidation yielded a 4:1 mixture of 19,20:16,17-EDP exclusively as (S,R) enantiomers. Epoxidation with the mutant (F87V) yielded a 1.6:1 mixture of 19,20:16,17-EDP; the 19,20-EDP fraction was ∼9:1 (S,R):(R,S), but the 16,17-EDP was exclusively the (S,R) enantiomer. To access the (R,S) enantiomers of these EDPs, we used a short (four-step) chemical inversion sequence, which utilizes 2-(phenylthio)ethanol as the epoxide-opening nucleophile, followed by mesylation of the resulting alcohol, oxidation of the thioether moiety, and base-catalyzed elimination. This short synthesis cleanly converts the (S,R)-epoxide to the (R,S)-epoxide without loss of enantiopurity. This method, also applicable to eicosapentaenoic acid and arachidonic acid, provides a simple, cost-effective procedure for accessing larger amounts of these metabolites.

Keywords: chemoenzymatic synthesis, cytochrome P450, docosahexaenoic acid, polyunsaturated fatty acids, lipids/chemistry, epoxy fatty acids, epoxide inversion

As researchers begin to untangle the complex role that PUFAs play in human physiology and pathology, epoxy PUFAs, a class of bioactive metabolites produced by the cytochrome P450 (P450) pathway, have been the subject of increased investigation. These bioactive metabolites are transient, being quickly hydrolyzed to the corresponding 1,2-diols by soluble epoxide hydrolase (1). Despite their short half-life, the PUFAs’ epoxides, such as the regioisomeric epoxyeicosatrienoic acids [EETs, derived from arachidonic acid (AA, 4)] and epoxydocosapentaenoic acids [EDPs, derived from DHA (1)] have shown a variety of interesting biological effects (2). Both omega-6 and omega-3 PUFA epoxides are important autocrine/paracrine mediators and play a critical role in a variety of biological systems, including regulation of inflammation and blood pressure (3–7), pain perception (1, 8, 9), and angiogenesis (10), and they also have protective effects on various organs such as the heart and brain (9, 11, 12). In most cases, the epoxide metabolites derived from DHA are more potent than those derived from 4 (structures of DHA and 4 and relevant numbering is shown in Scheme 1). Metabolism of DHA to EDPs is believed, to some extent, to be responsible for the beneficial effects of consumption of DHA, as increased dietary DHA would produce increased beneficial EDPs. It is also possible that DHA could outcompete 4 in the P450 pathway (13), and thus EDPs (or other DHA-derived mediators) could be produced instead of proinflammatory eicosanoids (such as prostaglandins) or less potent EETs.

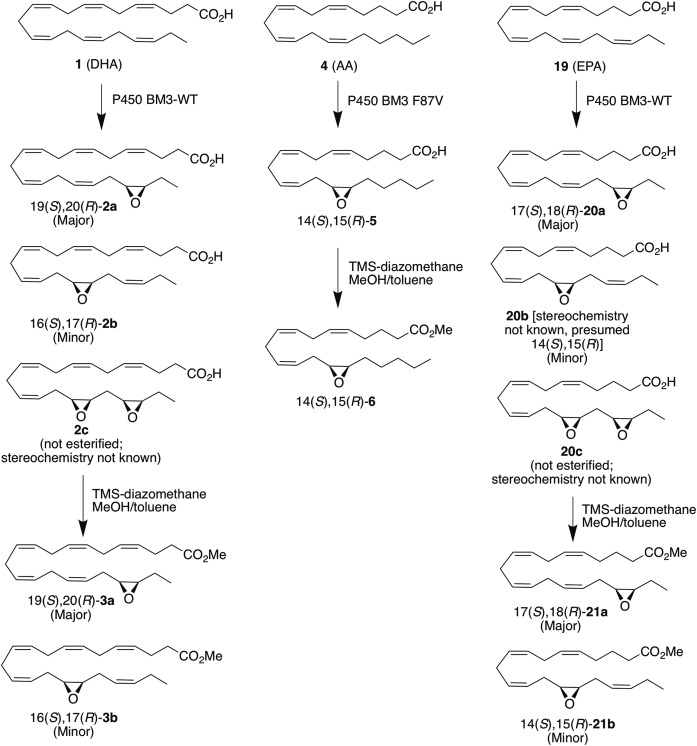

Enzymatic synthesis of EDP regioisomers, EEQs, and EETs.

|

Scheme 1. |

PUFA epoxide regioisomers have shown differing biological activities. Although regioisomer- and enantiomer-specific biological effects of EETs and epoxyeicosatetraenoic acids [EEQs; epoxides derived from eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 19)] have been demonstrated (14, 15), EDPs are generally much less studied than EETs, and the biological activity of EDP enantiomers is largely unknown. Ergo, interest in these metabolites (especially the 16,17- and 19,20- regioisomers of EDP, which are the most abundant metabolites of DHA produced in vivo) (13, 16) has increased recently because of the many reported benefits of fish oil supplements (17), which are rich in DHA. In fact, omega-3 FAs are currently one of the most-consumed natural products in the United States (18). As such, there is now considerable demand for these epoxy FAs and their derivatives as tool compounds, probes, and potential drug leads.

Production of epoxy FAs by chemical means (e.g., epoxidation with meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid or other peroxyacids) is neither regioselective nor enantioselective, and tedious separations, including expensive chiral chromatography, are necessary to obtain pure compounds, and the amounts obtainable by chiral HPLC are often miniscule. Total synthesis can also be used, as it has been for DHA (19) and EEQs (20), but it has not been performed for EDPs, and it is often time-consuming (requiring multiple steps) and gives low yields overall, which makes scale-up impractical. Enzymatic or chemoenzymatic synthesis has emerged as a recent alternative to prepare difficult-to-access compounds. Enzymatic reactions are highly stereoselective, as many biological processes preferentially utilize one enantiomer of a given compound.

Several reports have detailed enantioselective epoxidation of unsaturated FAs (21–24) by BM3 (CYP1021A) or its mutants. BM3, isolated from Bacillus megaterium, possesses both a heme-containing oxidase domain and a reductase domain, which makes it one of the most efficient P450 enzymes in nature (25). BM3 has been extensively studied as a drug-metabolizing enzyme and is an attractive enzyme to use for synthesis, because it is soluble, highly active, easily expressed, can be used crude or partially purified, and is readily amenable to engineering by mutagenesis. Lucas et al. (24) reported that the BM3 mutant (F87V) also has stereoselective monooxygenase activity toward DHA, although optimization of this reaction (solvent, time, and cofactor loading) for large-scale epoxidation of DHA has not been performed. In this report, we describe the optimization of the enantioselective chemoenzymatic epoxidation of DHA by BM3 enzymes (WT and the F87V mutant) to produce larger amounts of enantiopure 19,20 and 16,17-EDP and a short, optimized chemical inversion method to access the enantiomers opposite of those produced by the enzyme. We also used this strategy to produce 17,18-EEQ (and its enantiomer) from 19 and also used the chemoenzymatic synthesis to prepare larger amounts of enantiopure 14,15-EET (6) from 4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of WT-BM3 and BM3 (F87V)

The plasmid [pBluescript SK(pBS)-BM3] was a generous gift from F. Ann Walker and was originally prepared by Dr. A. J. Fulco (26, 27). Plasmid transformation, purification, site-directed mutagenesis, PCR, and DNA sequencing are described in detail in the supplemental data. Protein expression was performed according to the published procedure with slight modifications. DH5α Escherichia coli transfected with pBS-WT-BM3 or pBS-BM3 (F87V) was grown in LB broth (Lennox, Sigma Life Sciences) (5 ml) with ampicillin (0.500 mg, Sigma Life Sciences). The cell culture was shaken at 37°C for 24 h. The culture (5 ml) was then added into LB broth (500 ml) with added ampicillin (0.050 g). The culture was then shaken at 37°C for 6 h at 220 rpm, followed by 30°C for 18 h at 220 rpm. The culture was centrifuged at 1,000 g at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was stored at −78°C overnight. The pellet was thawed on ice and resuspended in ice-cold suspension buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, pH 7.8, 40 ml). The cells were lysed by sonication using an ultrasonic homogenizer [(Cole-Parmer Instrument Co., Chicago, IL, Output Power Setting, Cycle: sonication (1 min) – rest (1 min) on ice, six times]. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 11,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and was further centrifuged at 11,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then purified by strong anion exchange chromatography (Q SepharoseTM Fast Flow resin, diameter: 2.8 cm × 6 cm, column volume: 37 ml) at 4°C. The column was preequilibrated with buffer A [(10 mM Tris, pH 7.8, 5 column volumes (CV)]. The cell lysates were introduced to the column, and the column was first washed with buffer A (three column volumes). The protein was then eluted with buffer B (10 mM Tris and 600 mM NaCl, six column volumes), and the brown eluent was collected. As the partially purified protein solution was not used immediately, it was mixed with an equal amount of glycerol, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −78°C.

Small-scale optimization of epoxidation of DHA by WT-BM3 and BM3 (F87V)

The objective for this optimization was to find the optimum enzyme, cofactor, and substrate concentrations for the large-scale synthesis. Therefore, a series of different enzyme and substrate concentrations were assessed for epoxidation of DHA. The desired concentration of partially purified WT or mutant BM3 enzyme (from 5 to 40 nM) and the desired concentration of DHA (200 and 400 µM) were dissolved in potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 10 ml). The reaction mixture was preincubated and stirred at 25°C for 5 min. To initiate the reaction, NADPH (Acros Organics; 100 mM dissolved in 0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.5–1.5 equivalent (equiv.) relative to DHA) was added. For the rate study, at times 0, 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 40 min, 50 µl of the reaction mixture was added to 6 µl of 1 M oxalic acid (to quench the reaction). For the optimization study, 50 ul of the reaction mixture was added to 6 ul of 1 M oxalic acid at 30 min. The resulting mixture was further diluted 100-fold with methanol (MeOH) (5 ml), and the resulting mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the precipitated protein and salt. The supernatant (1 ml) was then transferred to an amber HPLC vial (1.5 ml capacity) and stored at −20°C until LC/MS/MS analysis (detailed methods for LC/MS/MS analysis are described in the supplemental data, pages S4–S6).

Small-scale DHA epoxidation by BM3 using NADPH recycling system

The BM3 (20 nM), DHA (200 µM), glucose-6-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich®, G6P, 200 µM), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH; Promega Life Sciences, 3 units/ml) was dissolved in potassium phosphate buffer (0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 10 ml). The reaction mixture was preincubated and stirred at 25°C for 5 min. To initiate the reaction, NADPH (100 mM, dissolved in 0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 0.1 equiv. relative to DHA, 2 µl) was added. For the rate study, at times 0, 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 40 min, 50 µl of the reaction mixture was added to 6 µl of 1 M oxalic acid. The resulting mixture was diluted 100-fold with MeOH (5 ml), and the resulting mixture was centrifuged at 10000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the precipitated protein and salt. The supernatant (1 ml) was then transferred to an amber HPLC vial (1.5 ml capacity) and stored at −20°C until LC/MS/MS analysis (see supplemental data, pages S4–S6, for instruments and conditions.)

Scale-up enzymatic epoxidation [and preparation of EDP ester substrates 19(S),20(R)-3a and 16(S),17(R)-3b] using WT-BM3

Note that TMS-diazomethane is toxic by contact and inhalation and should only be used in a fume hood while wearing proper personal protective equipment. To stirring reaction buffer (0.12 M potassium phosphate, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 l) was added DHA (0.308 g, 0.940 mmol) dissolved in DMSO (18.8 ml) and a thawed aliquot of enzyme (20 nM final concentration; the purified enzyme concentration was determined based on the published method) (28). The reaction mixture was initiated by addition of NADPH tetrasodium salt (Acros Organics, 808 mg, 0.940 mmol) dissolved in reaction buffer (8.7 ml). The mixture was kept oxygenated by bubbling air through the reaction with an air-filled balloon. After 20–30 min, the absorbance of the mixture at 340 nm was measured with a nanodrop 2000C Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) to confirm that all NADPH had been consumed (no absorption peak at 340 nm). The reaction was quenched by dropwise addition of 1 M oxalic acid, until the pH of the reaction mixture was ∼4. The quenched mixture was extracted with Et2O (3× 2 l, 6 l total), and the ethereal extracts were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (see General chemistry procedures section for instruments and cartridges), eluting with a gradient of 10% ethyl acetate (EtOAc) in hexanes to 60% EtOAc in hexanes (40 g cartridge, 22 min) to yield three fractions: an inseparable mixture of the mono-epoxides 19(S),20(R)-2a and 16(S),17(R)-2b (0.151 g, 47%), recovered DHA (0.074 g, 24%), and the 16,17,19,20-di-epoxide 2c (stereochemistry unknown, 0.076 g, 22%). The obtained mixture of monoepoxides was diluted with anhydrous MeOH (2 ml) and anhydrous toluene (3 ml), and TMS-diazomethane (0.260 ml, 0.520 mmol, 2 M solution in hexanes) was added. After 10 min, additional TMS-diazomethane (0.1 mmol, 0.050 ml, 2 M solution in hexane) was added until a pale yellow color persisted in the reaction. After a total of 40 min, the mixture was concentrated, and the residue was directly purified by flash column chromatography, eluting with 4% EtOAc in hexanes (40 g cartridge, 22 min). Pure fractions were pooled, and the mixed fractions were rechromatographed using the same solvent system as mentioned above to yield 19(S),20(R)-3a (0.116 g, 74%) and 16(S),17(R)-3b (0.029 g, 19%), both as clear oils (total yield, 93%).

All cis-methyl 19S,20R-epoxydocosapentaenoate [19(S),20(R)-3a].

1H-NMR (500 MHz; CDCl3): δ 5.54-5.35 (m, 10 H), 3.68 (s, 3 H), 2.97 (td, J = 6.4, 4.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.91 (td, J = 6.3, 4.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.85-2.82 (m, 8 H), 2.44-2.36 (m, 5 H), 2.27-2.21 (m, 1 H), 1.65-1.51 (m, 3 H), 1.06 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz; CDCl3): δ 173.5, 130.4, 129.3, 128.37, 128.21, 128.17, 128.11, 128.07, 127.89, 127.83, 124.5, 58.3, 56.5, 51.6, 34.0, 26.2, 25.80, 25.64 (2 C), 25.57, 22.8, 21.1, 10.6; high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) (APCI, positive mode) m/z: 359.2580 (MH+, calcd 359.2581); [α]20D (c 1, MeOH): −3.2°.

All cis-methyl 16S,17R-epoxydocosapentaenoate [16(S),17(R)-3b].

1H-NMR (500 MHz; CDCl3): δ 5.57-5.35 (m, 10 H), 3.68 (s, 3 H), 2.99-2.95 (m, 2 H), 2.87-2.83 (m, 6 H), 2.47-2.37 (m, 6 H), 2.29-2.21 (m, 2 H), 2.11-2.05 (m, 2 H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H). 13C-NMR (126 MHz; CDCl3): δ 173.5, 134.4, 130.5, 129.3, 128.4, 128.16, 128.10, 127.90, 127.81, 124.4, 123.1, 56.52, 56.36, 51.6, 34.0, 26.21, 26.07, 25.81, 25.64, 25.57, 22.8, 20.8, 14.2; HRMS (APCI, positive mode) m/z: 359.2567 (MH+, C23H35O3+ calcd 359.2581); [α]20D (c 1, MeOH): −4.2°.

When the F87V mutant was used instead, DHA (0.657 g, 2.00 mmol) and NADPH (Acros Organics, 1.71 g, 2.00 mmol) in DMSO (40 ml), purification by flash column chromatography, eluting with a gradient of 10% EtOAc in hexanes to 50% EtOAc in hexanes (40 g cartridge, 20 min), afforded three fractions: an inseparable mixture of mono-epoxides 16(S),17(R)-2b and 19(S),20(R)-2a (0.251 g, 729 µmol, 36%), recovered DHA (0.233 g, 33%), and the 16,17, 19,20-di-epoxide 2c (0.160 g, 22%). After esterification and purification (same conditions as described above), 19(S),20(R)-3a (0.139 g, 54%) and 16(S),17(R)-3b (0.087 g, 33%), both as clear oils (total yield, 87%). The NMR spectra for these samples were identical to those for 19(S),20(R)-3a and 16(S),17(R)-3b prepared using the WT-BM3. Saponification of a sample of the purified regioisomers and chiral HPLC (supplemental data and supplemental Fig. S6) indicated that the enantiomeric ratio (er) of 19(S),20(R)-2a was 89:11 [78% enantiomeric excess (ee)], consistent with that reported (24), and 16(S),17(R)-2b was >99:1er (>99% ee).

Scale-up synthesis of 14S,15R-EET ester [14(S),15(R)-6] using BM3 (F87V)

The procedure for the synthesis of 14(S),15(R)-6 was similar to that for the synthesis of the EDP esters, except that 4 (Nu-Chek Prep, Inc., 0.244 g, 0.800 mmol), NADPH (Acros Organics, 688 mg, 0.8 mmol) dissolved in DMSO (16 ml) and BM3 (F87V, 20 nM) were used instead. The crude mixture isolated from the enzymatic reaction was purified by column chromatography, eluting with 50% EtOAc in hexanes, to yield a fraction consisting of both of 4 and 14(S),15(R)-5 (0.200 g). This combined fraction was immediately esterified with TMS-diazomethane (0.340 ml of a 2 M solution in hexanes) as described above. After concentration, the residue was directly purified by flash column chromatography, eluting with 5% EtOAc in hexane to yield 14(S),15(R)-6 (0.138 g, 51.6%) as a clear oil.

All cis-methyl 14S,15R-epoxyeicosatrienoate [14(S),15(R)-6].

1H-NMR (500 MHz; CDCl3): δ 5.53-5.33 (m, 6 H), 3.67 (s, 3 H), 2.95-2.92 (m, 2 H), 2.81 (dt, J = 17.8, 5.8 Hz, 4 H), 2.40 (dt, J = 14.1, 6.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.23 (dt, J = 14.1, 6.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.11 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 2 H), 1.71 (quintet, J = 7.4 Hz, 2 H), 1.56-1.41 (m, 4 H), 1.38-1.30 (m, 4 H), 0.90 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3 H). 13C-NMR (126 MHz; CDCl3): δ 174.0, 130.4, 129.0, 128.7, 128.4, 127.8, 124.5, 57.2, 56.4, 51.5, 33.4, 31.7, 27.7, 26.5, 26.28, 26.26, 25.79, 25.60, 24.7, 22.6, 14.0; HRMS (ESI, positive mode) m/z: 335.2582 (MH+, C21H35O3+ calcd 335.2581); [α]20D (c 1, MeOH): −5.7°.

Scale-up enzymatic epoxidation (and preparation of EEQ ester substrates 17(S),18(R)-21a and 21b) using WT-BM3

The procedure for the synthesis of 17(S),18(R)-21a is similar to that for the synthesis of the EDP esters, except 19 (0.362 g, 1.2 mmol, Nu-Chek Prep, Inc.) and NADPH (1.03 g, 1.2 mmol) dissolved in DMSO (24 ml) was used. The crude residue obtained after the enzymatic reaction was purified by flash column chromatography, eluting with a gradient of 10% EtOAc in hexanes to 60% EtOAc in hexanes (40 g cartridge, 35 min) to yield three fractions: an inseparable mixture of mono-epoxides 17(S),18(R)-20a and 20b (stereochemistry unknown, 0.215 g, 56%), recovered 19 (0.007 g, 3%), the 14,15,17,18-di-epoxide 20c (stereochemistry unknown, 0.024 g, 6%), a mixture of 19-HEPE and unidentifiable, inseparable oxidation products (0.036 g), and a mixed fraction of 20c and the oxidation products (0.012 g). The monoepoxide fraction was immediately esterified with TMS-diazomethane (0.810 mmol, 0.405 ml, 2 M solution in hexanes) as described above. After concentration, the residue was directly purified by flash column chromatography, eluting with a gradient of hexanes to 5% EtOAc in hexanes (40 g cartridge, 30 min). Pure fractions were pooled, and the mixed fractions were rechromatographed (12 g cartridge, 5% EtOAc in hexanes, 15 min) to yield 17(S),18(R)-21a (0.179 g, 80%) and 21b (stereochemistry unknown, 0.013 g, 6%) both as clear oils (total yield, 86%).

All cis-methyl 17S,18R-epoxyeicosatetraenoate (17(S),18(R)-21a).

1H-NMR (500 MHz; CDCl3): δ 5.53-5.34 (m, 8 H), 3.67 (s, 3 H), 2.96 (td, J = 6.4, 4.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.90 (td, J = 6.3, 4.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.85-2.79 (m, 6 H), 2.44-2.38 (m, 1 H), 2.32 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.26-2.20 (m, 1 H), 2.11 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 2 H), 1.71 (quintet, J = 7.4 Hz, 2 H), 1.66-1.50 (m, 2 H), 1.05 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz; CDCl3): δ 174.1, 130.4, 129.0, 128.8, 128.39, 128.31, 127.97, 127.81, 124.5, 58.3, 56.5, 51.5, 33.4, 26.5, 26.2, 25.80, 25.63, 25.60, 24.8, 21.1, 10.6; HRMS (ESI, positive mode) m/z: 333.2424 (MH+, C21H33O3+ calcd 359.2424), [α]20D (c 1, MeOH): −6.0°.

All cis-methyl 14,15-epoxyeicosatetraenoate (21b).

1H-NMR (500 MHz; CDCl3): δ 5.57-5.35 (m, 8 H), 3.68 (s, 3 H), 2.99-2.95 (m, 2 H), 2.86-2.80 (m, 4 H), 2.47-2.40 (m, 2 H), 2.33 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.29-2.21 (m, 2 H), 2.14-2.05 (m, 4 H), 1.71 (quintet, J = 7.4 Hz, 2 H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz; CDCl3): δ 174.1, 134.4, 130.5, 129.0, 128.7, 128.5, 127.7, 124.4, 123.1, 56.52, 56.36, 51.5, 33.4, 26.5, 26.21, 26.06, 25.80, 25.61, 24.7, 20.8, 14.2; HRMS (ESI, positive mode) m/z: 333.2431 (MH+, C21H33O3+ calcd 359.2424), [α]20D (c 1, MeOH): −4.6°.

Determination of km and kcat of DHA and racemic 2a with WT-BM3

kcat and km were determined according to the published method (29). Briefly, to a mixture of WT-BM3 (5 nM) and DHA (from 5 to 40 µM) or racemic 2a (from 8.4 to 67 µM) in potassium phosphate buffer [(0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 1 ml] with maximum 1% DMSO, at 30°C, NADPH (100 mM, 2 µl) was added, and the reaction was monitored at 340 nm (ε340/NADPH = 6,220 M−1·cm−1) with a Cary 100 spectrophotometer. The reaction rate (µmol per second per nmol of BM3) at different concentrations of DHA or racemic 2a was then calculated based on the rate of consumption of NADPH measured with the spectrophotometer. The data were then fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation using SigmaPlot to calculate kcat (s−1) and km (M−1). The calculated kcat and km values are an average of triplicates.

Determination of Kd for DHA and racemic 2a with WT-BM3

The determination of the Kd for DHA and racemic 2a was performed according to the published procedure (29). UV-vis spectra (350–500 nm) were recorded using a Cary 100 spectrophotometer. The stock solutions of DHA and racemic 2a (2–100 mM) dissolved in DMSO (100 µl) were stored in glass vials to prevent them from being absorbed by the container. The UV-vis spectra were recorded on a solution of WT-BM3 (5 µM, 1 ml) at baseline. The BM3 solution was then titrated either with DHA or racemic 2a, and the corresponding spectra were measured after 5 min incubation after each addition of the compound until there was no change in the absorbance at 424 or 393 nm. The Kd of DHA and racemic 2a was calculated by KaleidaGraph using nonlinear least-squares regression analysis. The absorption at 424 nm and 393 nm was plotted against the concentration of either DHA or racemic 2a. The enzyme concentration and the absorption where the enzyme was fully saturated were determined prior to the calculation of the Kd using the following equation as described before (30):

where A is observed absorbance, Af is absorbance of free protein, Ab is absorbance of bound protein, Pt is the total protein concentration, and Rt is total reporting ligand concentration.

General chemistry procedures.

FAs and esters were purchased from Nu-Chek Prep, Inc. (Elysian, MN). All other chemicals for epoxide inversion were purchased from commercial vendors (Aldrich and Acros) and were used as received without further purification. 1H-NMR spectra were recorded at 500 MHz on an Agilent DD2 Spectrometer; 13C-NMR spectra were recorded at 126 MHz using the same instrument. Flash chromatography was performed on a Buchi Reveleris X2 flash purification system (equipped with an evaporative light scattering detector), using Buchi HP SiO2 or GraceResolv SiO2 cartridges, and monitoring/collecting using both UV absorption and ELSD, or on a Teledyne Isco CombiFlash RF Lumen flash purification system, using the same columns and detection methods. TLC was performed on Analtech Uniplate 250 micron TLC plates; visualization was performed with potassium permanganate (KMnO4) stain, and where appropriate, short-wave (254 nm) UV light. Microwave reactions were performed using an Anton Paar Monowave 400, using Anton Paar G10 or G30 microwave vials. Mass spectrometry was performed at the Michigan State University Mass Spec and Metabolomics Facility. Data were collected using a Waters Xevo G2-XS QTOF system and processed with MassLynx software. Polarimetry was performed using a Perkin Elmer 341 Polarimeter in a 10 cm cell. HPLC was performed using a Shimadzu Prominence LC-20AT analytical pump and SPD-20A UV-vis detector, monitoring at 205 and 208 nm, at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Chiral HPLC was performed using a Phenomenex Lux cellulose-3 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm, 1000 Å) eluting with isocratic 45% 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3) in MeOH (30 min), with a sample concentration of 0.5 mM. For the sake of completeness, both er and ee are reported. More details are available in the supplemental data. Achiral HPLC (for determining chemical purity) was performed using a Zorbax Eclipse XDB C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm, 100 Å), eluting with a gradient of 60% acetonitrile (MeCN) in water (H2O) +0.05% formic acid in each solvent to 90% MeCN or 95% MeCN in H2O +0.05% formic acid (45 or 60 min), with a sample concentration of 0.5–2 mM.

Inversion of epoxide stereochemistry.

For general procedures, see Schemes 2 and 3; see supplemental data for specific substrates.

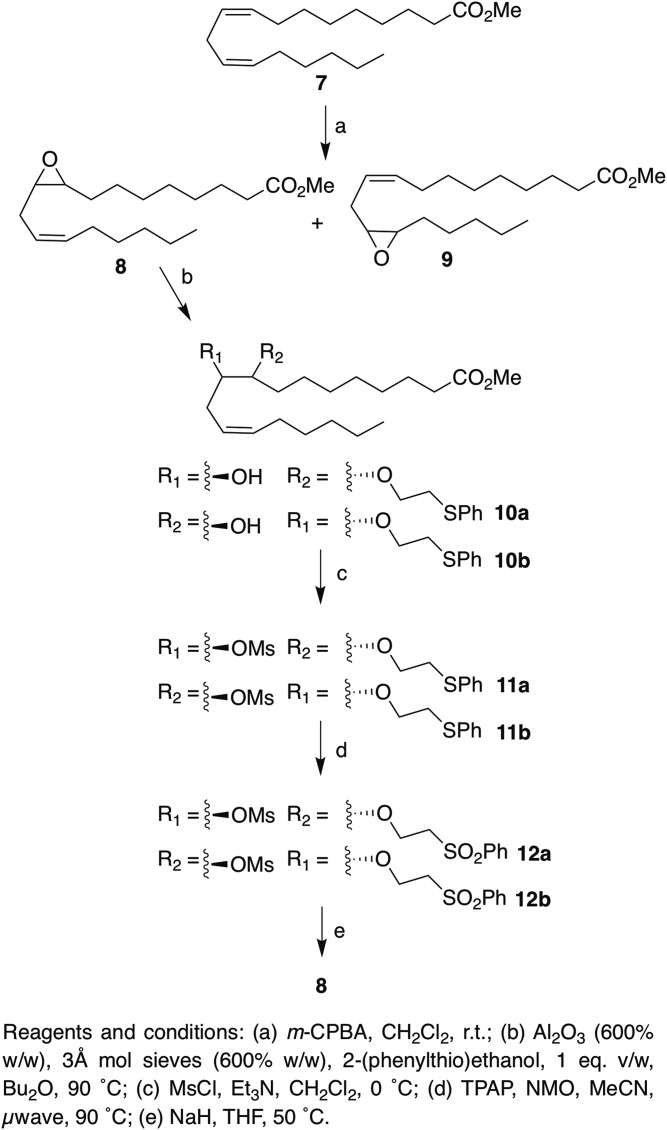

Epoxide inversion on model substrate.

|

Scheme 2. |

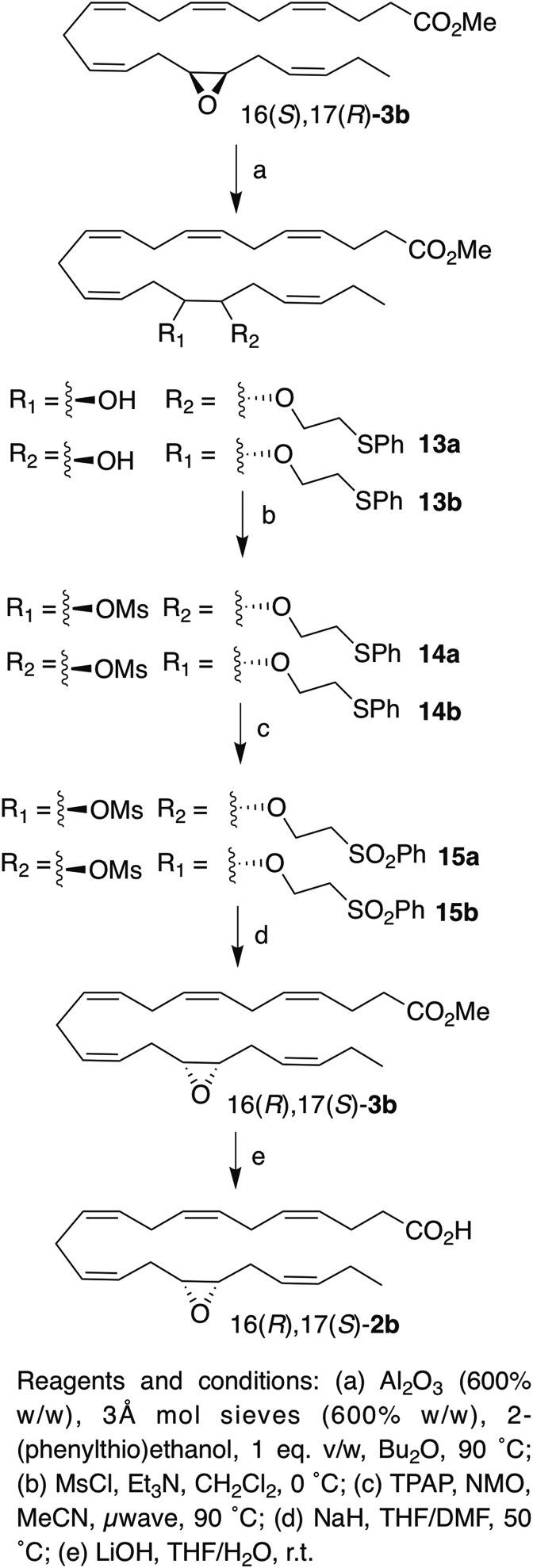

Inversion of 16(S),17(R)-3b.

|

Scheme 3. |

Step 1. Epoxide ring-opening.

A heavy-walled glass pressure tube with a Teflon screw-cap was charged with neutral alumina (Aldrich WN-6, activity grade Super I, 600% weight relative to the epoxide) and crushed 3 Å molecular sieves (Fisher Grade 562, 600% weight relative to the epoxide). The solids were evacuated under house vacuum (∼100 torr) while the tube was heated with a Bunsen burner (to ∼200°C) until bubbling of the solids ceased, which indicated that water was removed. A magnetic stirbar was added, the tube was cooled under argon, and anhydrous dibutyl ether (Bu2O, 2 ml/100 mg of epoxide) was added, followed by 2-(phenylthio)ethanol (0.1 ml for every 0.1 g of epoxide). The mixture was stirred for 5 min, and the epoxide (as a solution in Bu2O, 33 mg/ml epoxide) was added. The tube was further flushed with argon, sealed, and heated to 90°C for 18 h. Following the reaction, the tube was cooled to room temperature. The mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was collected. The alumina/sieves were further washed with Bu2O (5 ml/100 mg of epoxide, with the aid of sonication), and with ethyl ether (Et2O) (3 × 20 ml) until no more UV absorbance was detected in the washed fraction by TLC. The combined filtrate and washed fractions were concentrated to dryness, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc; specific gradients/conditions for individual compounds are described in the supplemental data) to yield the ring-opened product.

Step 2. Mesylation.

The ring-opened product was diluted with anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 ml/100 mg of ring-opened product) and cooled to 0°C in an ice bath under argon. Triethylamine (Et3N, 2 equiv.) and methanesulfonyl chloride (1.1–1.2 equiv.) were then added, and the mixture was stirred at 0°C for 20 min and monitored by TLC. The reaction was then quenched by an equal volume of saturated aqueous (sat. aq.) sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), and the organic layer was collected. The aqueous layer was extracted with dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) (3× original reaction volume). The organic layers were washed with water and sat. aq. sodium chloride (NaCl), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (CH2Cl2/EtOAc, specific gradients/conditions for individual compounds are described in the supplemental data) to yield the mesylate, free of transesterification products.

Step 3. Oxidation.

The mesylate was diluted in dry MeCN (0.75–1 ml/10 mg) in a microwave vial. N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide (NMO, 9–10 equiv.) and tetra-n-propylammonium perruthenate [(TPAP), 5–16 mol% or 0.05–0.16 equiv.] was added (as a solution in dry MeCN). The mixture was purged with argon, sealed, and heated under microwave irradiation (using an Anton Paar Monowave 400) at 90°C. The reaction was monitored every 10–20 min, and more TPAP/NMO (see supplemental data for specifics for individual compounds) was added, and heating continued as needed until TLC indicated either reaction completion or no further progress. The mixture was then concentrated, and the residue was diluted in EtOAc/hexanes (1:1, approximately the original reaction volume) and filtered to remove TPAP. The residue was washed with EtOAc until no more product was detected by TLC in the filtrate (typically 3×), the filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc, specific gradients/conditions for individual compounds are described in the supplemental data) to yield the sulfone. If necessary, any isolated sulfoxide was resubjected to the reaction conditions, with identical workup and purification.

Step 4. Elimination.

An oven-dried and cooled sealable vial was charged with sodium hydride (1.1–1.5 equiv of a 60% dispersion in mineral oil) and diluted in dry tetrahydrofuran (THF) or 4.5:1 THF/N,N-dimethylformamide [(THF/DMF), 0.5–1 ml/20 mg of sulfone]. The sulfone was added as a solution in dry THF or 4.5:1 THF/DMF (1 ml/20 mg of sulfone), and the mixture was flushed with argon, sealed, and heated to 50°C. The reaction was monitored by TLC until the sulfone was consumed (typically 1–5 h), and additional solvent or sodium hydride was added as necessary if the reaction did not appear to be proceeding after 1–2 h. Following completion of the reaction, the mixture was partitioned between sat. aq. NaHCO3 and EtOAc, the layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3×). The organic layers were washed with 5% aq. NaCl (3×) and sat. aq. NaCl (3×), dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc, specific gradients/conditions for individual compounds are described in the supplemental data) to yield the inverted (or in the case of 12a/12b, recovered) epoxide.

Step 5. Saponification.

The epoxy fatty ester was diluted in THF/H2O (4:1, ∼1.1 ml/0.05 g ester), lithium hydroxide (2 M, 3 equiv.) was added, and the mixture was flushed with argon and stirred rapidly overnight. The reaction was quenched by the dropwise addition of 88% formic acid until the pH of the water was ∼4, and water and EtOAc were then both added. The layers were separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAc (3×). The organic layers were washed with water (2×) and sat aq. NaCl, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated, and the residue was azeotroped twice with hexanes (to remove residual formic acid). The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc, specific gradients/conditions for individual compounds are described in the supplemental data) to yield the FFA after diluting with MeOH, refiltering to remove particulate matter, and reconcentrating.

RESULTS

Optimization of the enzymatic synthesis of EDPs

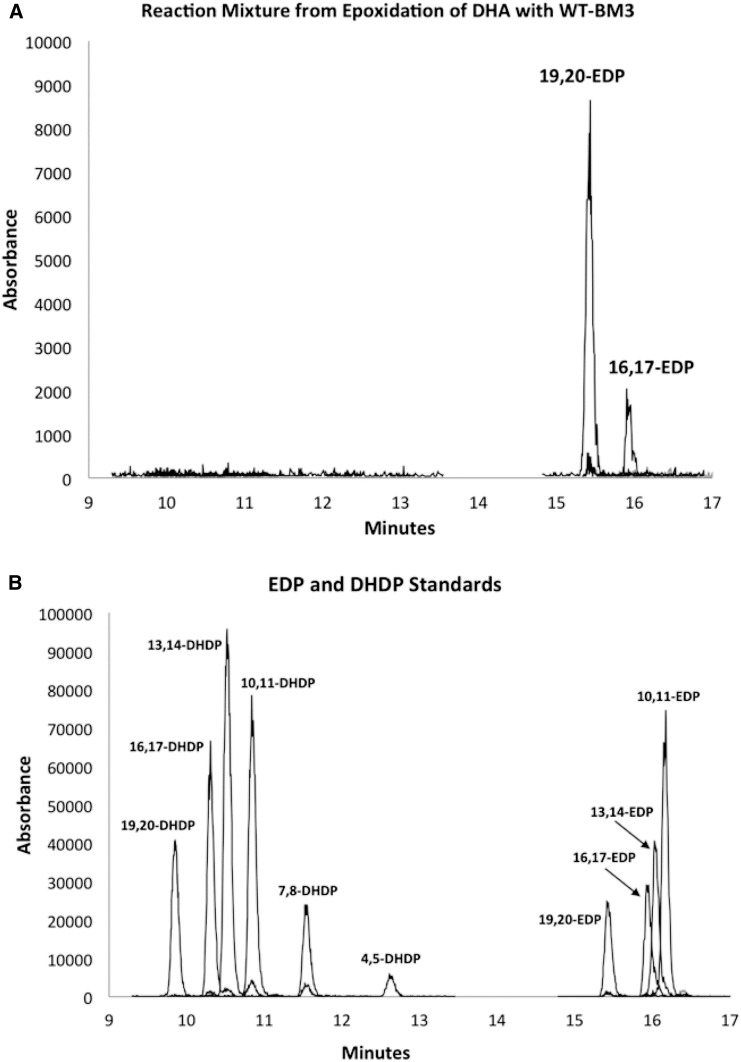

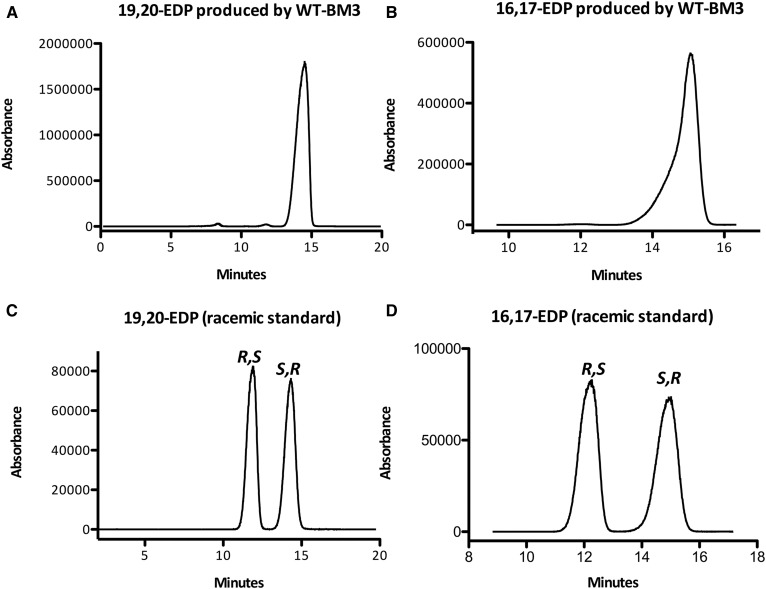

Although WT-BM3 and its mutant (F87V) have been reported to produce desired PUFA epoxides (with high regioselectivity and enantioselectivity) from AA (4), EPA (19), and linoleic acid, these enzymes have never been tested in detail with DHA. Here, we first investigated the regioselectivity and enantioselectivity of monooxygenation by both WT-BM3 and BM3 (F87V). WT-BM3 efficiently epoxidizes DHA (km = 14.5 ± 1.5 µM, kcat = 4750 ± 908 min−1; Table 1) to 19,20-EDP and 16,17-EDP in almost a 9 to 1 ratio (Fig. 1A), whereas the same enzyme hydroxylates 4 to hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (31). The identity of the regioisomers produced was confirmed by comparison of HPLC retention times of the products to those of authentic standards of EDPs and dihydroxydocosopentaenoic acids (DHDPs) (diols). No diols or other regioisomeric EDPs were produced (Fig. 1B). In addition, we also found that the enzymatic epoxidation was highly enantioselective, with WT-BM3 producing exclusively both 16(S),17(R)-2b (≥98:2 er and >97.6% ee) and 19(S),20(R)-2a in (≥99:1 er and >99% ee, Fig. 2); the identity of the enantiomers was previously reported (24). The epoxides were obtained in reasonable yield (33.8% yield of all EDPs combined), and the reaction is mostly complete within 15 min (supplemental Fig. S1). A summary of enzymatic reactions and their products are shown in Scheme 1.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters measured for WT-BM3 with different FAs

| Substrate | km (µM) | kcat (min−1) | Kd (µM) |

| DHA | 14.0 ± 1.5 | 4,750 ± 908 | 1.53 ± 0.02 |

| 2a (racemic) | 13.0 ± 1.1 | 3,190 ± 168 | 1.54 ± 0.18 |

Fig. 1.

LC/MS/MS analysis reveals that WT-BM3 produces 16,17-EDP (12%) and 19,20-EDP (88%) from DHA (A). No other regioisomers or diols (DHDPs) are obtained (assessed by comparison to standards) (B).

Fig. 2.

Chiral LC/MS/MS analysis reveals that WT-BM3 stereospecifically produces 19(S),20(R)-EDP [19(S),20(R)-2b, ≥99.5% ee, >99.5:0.05 er] (A) and 16(S),17(R)-EDP [16(S),17(R)-3b, ≥97.6% ee, >98:2 er] (B). Racemic standards are shown on the bottom. The enantiopurities remain consistent upon scaleup.

Given this encouraging result, we ran a small set of optimizations on the enzymatic synthesis of 19(S),20(R)-2a with BM3. The effect of DHA concentration, enzyme concentration, and the ratio of DHA to NADPH were investigated in order to further develop conditions for preparing 19(S),20(R)-2a on a larger scale. As shown in Table 2, the conditions in entry 5 give the best overall yield, which offers several advantages: 1) minimum use of NADPH (a pricey cofactor) to produce the most EDPs and 2) a higher concentration of DHA, which minimizes the amounts of buffer and solvent used for epoxidation and extraction. Based on the study of the rate of product formation, we found that even with as little as 5 nM enzyme (with the maximum amount of DHA used), the reaction was complete within 15 min (supplemental Fig. S2). We did not increase the enzyme concentration beyond 20 nM, because the study with BM3 (F87V) and 4 indicated that increasing the enzyme concentration beyond 20 nM did not increase the overall yield of the epoxidized product (supplemental Table S7). Based on our results, an enzyme to substrate ratio of ≤1:20,000 is the ideal ratio for the production of EDPs (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of epoxidation of DHA with BM3 under different conditions

| Reaction Conditionsa | 2a (yield %)b | SEMc | 2b (% yield)b | SEMc | Overall Yield (%)b | SEMc | |||

| Entry | BM3 (nM) | DHA (µM) | NADPH (equiv. relative to DHA) | ||||||

| 1 | 10 | 200 | 1 | 45.5 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 0.03 | 51.6 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 5 | 400 | 1 | 21.1 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 23.9 | 0.6 |

| 3 | 10 | 400 | 1 | 30.5 | 0.5 | 4.7 | 0.02 | 35.2 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 20 | 400 | 0.5 | 23.8 | 0.2 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 27.5 | 0.3 |

| 5 | 20 | 400 | 1 | 44.3 | 0.5 | 6.4 | 0.08 | 50.6 | 0.6 |

| 6 | 20 | 400 | 1.5 | 41.3 | 0.03 | 6.2 | 0.06 | 47.5 | 0.1 |

| 7 | 20 | 200 | 1 | 28.8 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 33.8 | 1 |

The reaction was conducted in an open 20 ml vial. For the details, please refer to Materials and Methods.

Reaction was quenched by addition of reaction mixture (50 µl) to oxalic acid (1 M, 6 µl) at 30 min.

Yield was calculated based on the concentration of the EDPs detected by LC/MS/MS relative to the limiting reagent of the enzymatic reaction.

Standard error of measurement.

We then tested whether we could substitute NADPH with an NADPH regeneration system (G6P and G6PDH), which has been used in biocatalysis that uses NADPH (32) because NADPH itself is costly and relatively unstable. The amount of G6PDH used matched the total activity of the WT-BM3 in the reaction mixture. We found that the reaction rate with the regeneration system was much slower than with NADPH alone (supplemental Fig. S3). In addition, in order to keep up with the catalytic rate of BM3, the total cost of the amount of commercial enzyme (G6PDH) needed in the NADPH regeneration system is more expensive than the cost of NAPDH itself.

Scale-up enzymatic synthesis of 19(S),20(R)-2a and 16(S),17(R)-2b.

The conditions we identified from the optimization were used for the scale-up synthesis of 19(S),20(R)-2a and 16(S),17(R)-2b. Although the regioisomers from the enzymatic reactions were not separable at the free acid stage by flash chromatography, they were separable as the esters, and the two regioisomers from the enzymatic reactions were the same as those obtained on small scale, confirmed via 1H-NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry as 19(S),20(R)-3a (major) and 16(S),17(R)-3b (minor). Even on a large scale, WT-BM3 preferentially epoxidizes the last double bond of DHA, yielding an ∼4:1 mixture of 19(S),20(R)-3a:16(S),17(R)-3b in 47% overall yield, which is comparable to the that obtained on small scale. Again, both 19(S),20(R)-3a and 16(S),17(R)-3b were obtained in very high enantiopurity (>99:1 er, >99% ee).

The ratio of EDP regioisomers, however, changes depending on the enzyme used. When the mutant enzyme (F87V) was used on large scale instead, more 16(S),17(R)-3b was obtained following the esterification; the epoxides were obtained in 36% overall yield, and the ratio of 19(S),20(R)-3a to 16(S),17(R)-3b obtained was 61:39 (around 1.6:1), similar to that previously reported (63:37) (24). The enantiopurity of the 19(S),20(R)-3a was also consistent with prior reports (89:11 er, 78% ee; see supplemental Fig. S6B). Interestingly, unlike the 19(S),20(R)-3a, the 16(S),17(R)-3b obtained from F87V epoxidation was highly enantiopure (>99:1 er) as assessed by chiral HPLC; see supplemental Fig. S6A). We also tested the optimized scale-up conditions with BM3 (F87V) and 4, and we obtained a slightly better isolated yield (51.6% yield) of 14(S),15(R)-6 than that previously reported (45% yield) with the same enantiopurity [≥99:1 er and >99% ee (21)].

When both enzymes were used, unreacted DHA, as well as a product more polar than the monoepoxides, was isolated (Table 2). This polar product contained two oxygens as identified by mass spectroscopy [m/z 359 (MH−)] and was putatively identified as the overoxidation product, 16,17,19,20-di-epoxide 2c (Scheme 1); the mass spectrum contains a diagnostic fragment with m/z 245, consistent with fragmentation at the 16,17 epoxide. Although we are not sure what the absolute stereochemistry of 2c is, we anticipated that it might form because the kcat and kon between DHA and 2a (racemic) are very close (Table 1), and as the 2a is produced, it might compete with DHA for monooxygenation by BM3 (a summary of enzymatic reaction products produced on large scale is presented in Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Product distribution of epoxidation of DHA by BM3 enzymes on large scale

Scale-up enzymatic synthesis of EEQs.

Pleasingly, the optimized conditions were also applicable to EPA (19), and 56% yield of monoepoxides were isolated. As observed for DHA, when WT-BM3 is used, the last double bond of 19 is preferentially epoxidized, producing 17(S),18(R)-20a. The regioselectivity of epoxidation is considerably greater than for DHA; the ratio of 17(S),18(R)-20a to the 14,15 isomer 20b is nearly 14:1 (assessed after esterification; the regioisomers are not separable at the free acid stage; Scheme 1). The 17(S),18(R)-20a [enantioselectivity previously reported (23)] was highly enantiopure (>99:1 er, >98% ee) as assessed by chiral HPLC (supplemental Fig. S9A); we did not determine the enantiopurity of 20b, as it is obtained in only very small amounts (see Discussion). Like with DHA, an overoxidation product (the 14,15,17,18-di-epoxide 20c, stereochemistry unknown) is also obtained. Interestingly, small amounts of other oxidation products were also observed and were isolated as an inseparable mixture. By NMR, one of these products was identified as 19-HEPE; the others in the mixture were not readily identifiable, but mass spectroscopy suggests the presence of two oxygens in these side products, indicating overoxidation.

Optimization of epoxide inversion chemistry

With the esters 19(S),20(R)-3a and 16(S),17(R)-3b in hand, we next sought the optimal method for chemical inversion of the epoxide. Our early investigations focused on the use of cesium propionate (33) as an epoxide cleavage and inversion reagent. Although cesium propionate cleanly opened 19(S),20(R)-3a in DMF at 120°C, the epoxide isolated after mesylation and treatment with base was unfortunately racemic as assessed by optical rotation (see Discussion and supplemental Scheme S1). Multiple conditions were screened using the model substrates 8 and 9 [(prepared by epoxidation of methyl linoleate 7; Scheme 2)]. We did not use strongly acidic conditions out of concern of scrambling the stereochemistry at the epoxide. Although Cu(BF4)2 (34) was able to catalyze the opening of model substrate 9 by 2-(phenylthio)ethanol, the yield was low (<40%), multiple side products were observed, and this procedure did not translate to 3a (racemic or enantiopure). Only multiple polar decomposition products were observed (even in the absence of alcohol), likely because of interference by the substrate’s multiple double bonds. Additionally, Yb(OTf)3 (35), Er(OTf)3 (36), Al(OTf)3 (37), and hydrazine sulfate (38), as well as Zn(OTf)2, SiO2, Cs2CO3, and In(OTf)2, failed to catalyze the reaction of alcohols with racemic 3a, 8, or 9 (supplemental Table S4).

Falck et al. (21) reported the use of alumina as a catalyst for opening of EET esters with 2-(phenylthio)ethanol, but a detailed procedure was not reported. When 9 was treated with alumina (2,400% w/w) doped with 5% 2-(phenylthio)ethanol, as reported by Posner and Rogers (39) at 100°C, the starting epoxide was consumed in 5 h. However, extensive epoxide hydrolysis to the corresponding 1,2-diol had also occurred, and the desired epoxide-opening product was isolated in only 17% yield. Reducing the alumina loading to 600% (w/w) did not adversely impact the rate of epoxide opening, and pretreatment of the alumina by heating it at ∼200°C under house vacuum with an equivalent mass of molecular sieves (to remove trace amounts of water), completely abrogated competitive hydrolysis. For the model substrate 8, the epoxide-opening product was isolated in 88% yield as an approximately equal mixture of the regioisomers 10a and 10b (which were both converted to the same enantiomer of the epoxide at the end). Isolated along with 10a and 10b was a minor side product arising from transesterification with 2-(phenylthio)ethanol (confirmed by NMR spectroscopy and HRMS; see the supplemental data). These transesterification products are present in small amounts ranging from 5–12% depending on the nature of the starting epoxides and are separable from the methyl ester following mesylation. Treatment with mesyl chloride in CH2Cl2 in the presence of Et3N afforded the mesylates 11a and 11b in excellent (85–95%) yield within 20 min [as compared with the overnight tosylation reported by Falck et al. (21)]. Mesylation also afforded fewer by-products than tosylation. Oxidation of the thioethers of 11a and 11b to the sulfones 12a and 12b using the reported Ley conditions (10 mol% TPAP, 4 equiv. NMO, 80°C, overnight) (21) gave incomplete oxidation, and considerable quantities (>20%) of intermediate sulfoxide were also isolated. By contrast, performing this reaction under microwave irradiation (90°C) resulted in complete conversion in 10 min when 9 equiv. of NMO and 16 mol% TPAP were used and was also complete at 60°C in 40 min (see supplemental Table S5). Finally, treatment of 12a and 12b with 1,8-diazabicyclo(5.4.0.)undec-7-ene (DBU) as reported (80°C overnight in MeCN) yielded recovered 8 as expected, but side products (possibly from competitive alkene conjugation or isomerization) were also isolated, and performing the reaction in the microwave offered no advantages with regard to reaction speed or side products (see supplemental Table S6). Pleasingly, when DBU was replaced with a stronger, nonnucleophilic base (sodium hydride in THF) and the temperature was lowered to 50°C, the elimination was complete in several hours and gave 8 in similar yield to that reported without isolable side products. This full procedure is described in the supplemental data.

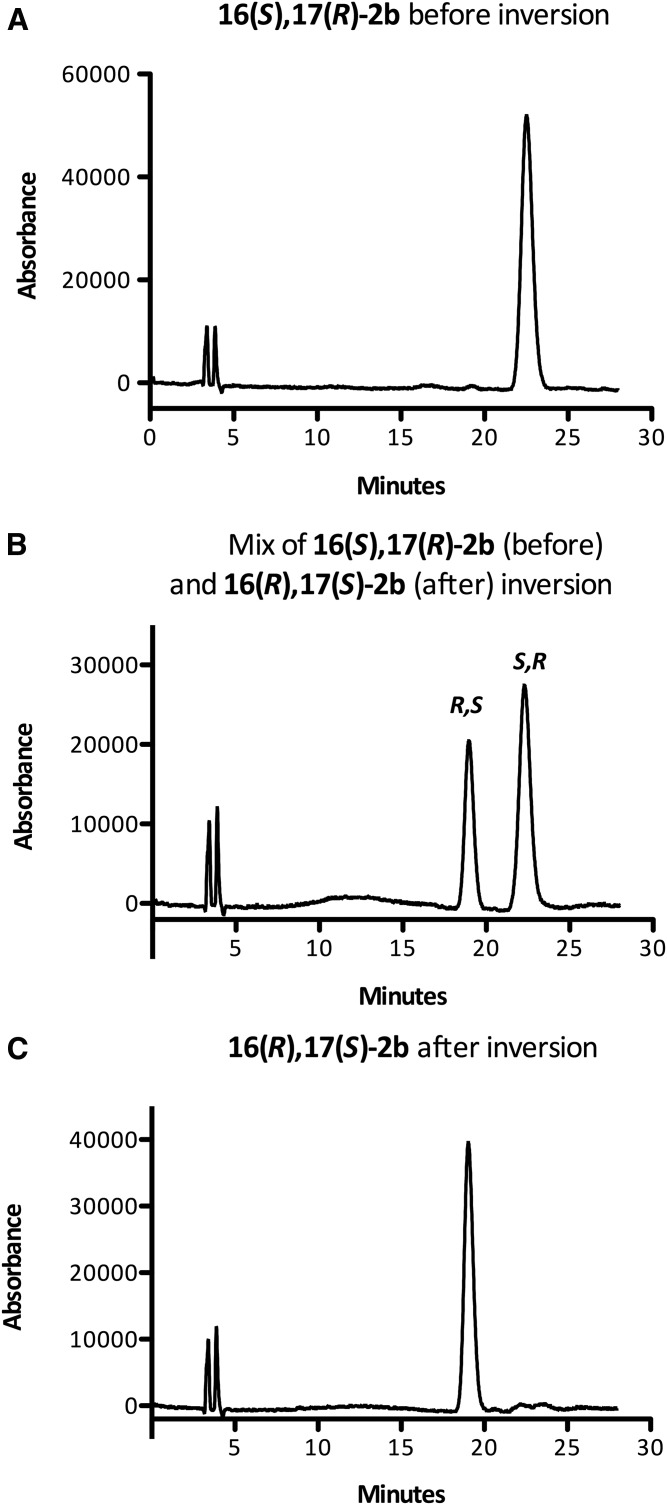

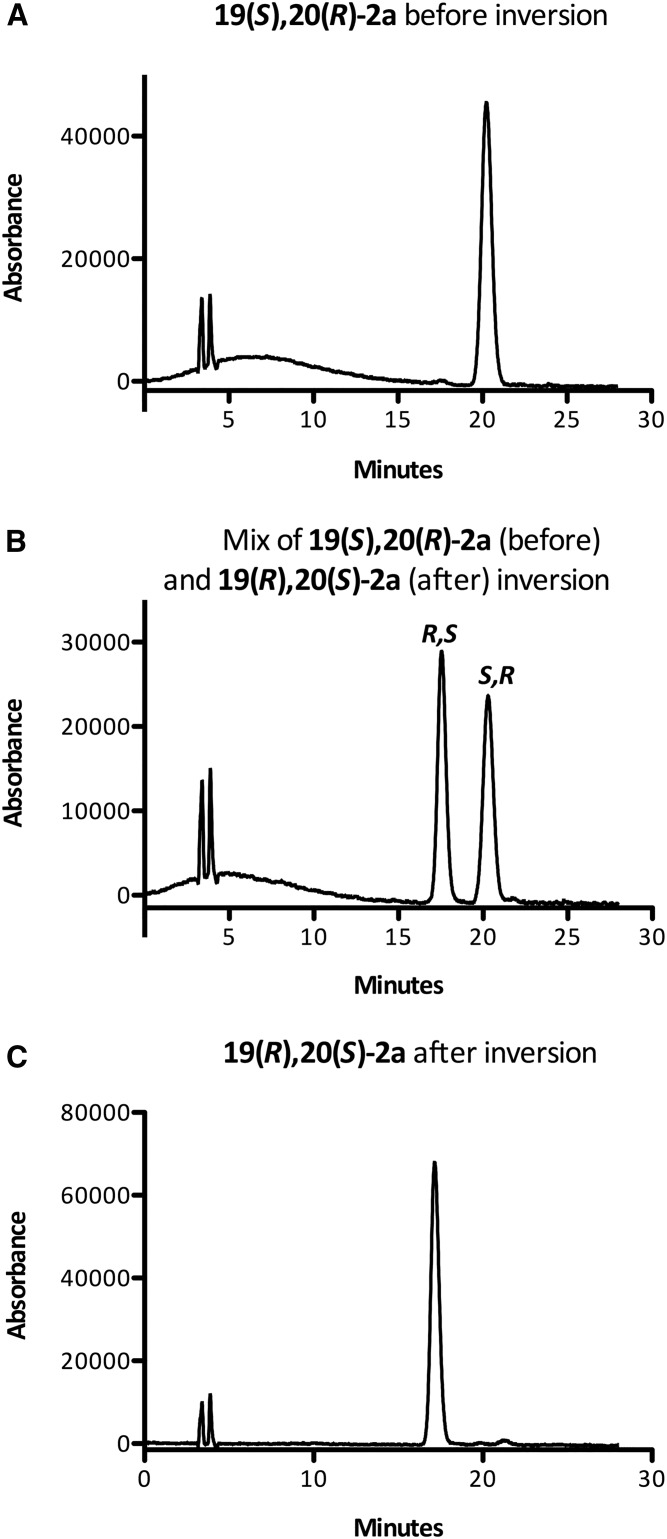

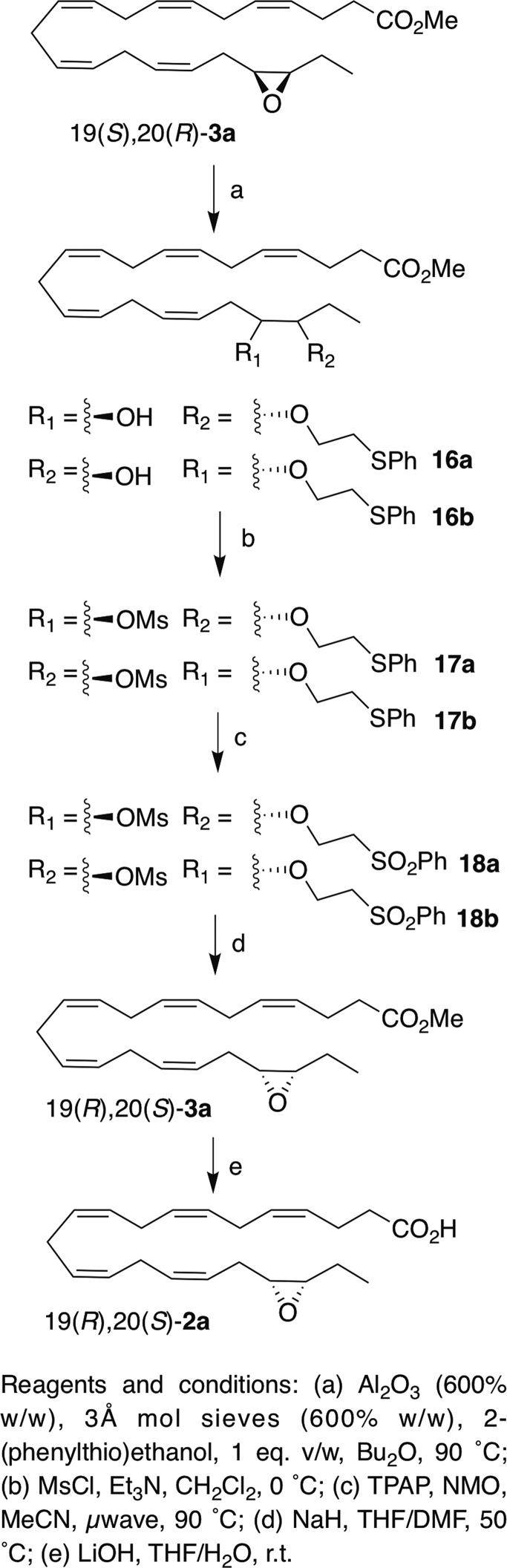

Pleasingly, this method was also applicable to 19(S),20(R)-3a and 16(S),17(R)-3b (Schemes 3 and 4). Alumina-catalyzed epoxide opening afforded similar yields of the regioisomeric adducts 16a and 16b (75%) and 13a and 13b (76%), respectively. Although the regioisomeric ratio is ∼1:1 for 8, it is 1.6:1 for 16(S),17(R)-3b and 2:1 for 19(S),20(R)-3a. Mesylation (and removal of transesterification products) afforded 17a and 17b [(from 19(S),20(R)-3a)] and 14a and 14b [(from 16(S),17(R)-3b)] in 89% and 92% yield, respectively. The rate of oxidation of the thioether was slower for EDPs than for the model linoleate substrate. For example, the oxidation of 14a/14b was quite sluggish, even at 90°C (proceeding only around halfway after 20 min), required additional TPAP (nearly 30 mol%), and unreacted sulfoxide was recovered after 50 min (although it could be isolated and converted to sulfone easily). Additionally, the reaction turned a dark reddish color, which did not occur with 11a/11b, and some of the substrate decomposed. Although we could not isolate any of the decomposition products, the slow reaction and partial decomposition are plausibly due to coordination of the ruthenium catalyst by the skipped polyene system, as this was not observed for 11a/11b. Nonetheless, 51% overall yield of 15a and 15b was obtained, and lowering the ruthenium catalyst loading for the initial oxidation of 17a/17b from 15 mol% to 5 mol% improved the yield of 18a/18b to 60% after reoxidizing the sulfoxide. The elimination of the sulfones proceeded smoothly in THF/DMF to yield the epoxides 19(R),20(S)-3a and 16(R),17(S)-3b in 78% and 76% yield, respectively. The methyl esters were then cleaved under basic conditions to yield 19(R),20(S)-2a and 16(R),17(S)-2b. The clean stereochemical inversion was confirmed by both polarimetry of the ester, which showed an opposite specific rotation of approximately equal magnitude following the inversion, and chiral HPLC of the free acids (Figs. 3, 4), which indicated that virtually no stereochemical erosion or racemization occurred during the inversion process [(16(R),17(S)-2b, ≥99:1 er, ≥98% ee], [19(R),20(S)-2a, 99.5:0.05 er, ∼99% ee]. The inverted EDPs were obtained in good chemical purity [∼95% for 16(R),17(S)-2b and ∼98% for 19(R),20(S)-2a] as assessed by HPLC (see supplemental Figs. S4 and S5); >99% purity can be easily obtained by preparative HPLC of this material (see the supplemental data). The epoxides were obtained in modest overall yields [for esters: 21% for 16(R),17(S)-3b, and 32% for 19(R),20(S)-3a], which were comparable to those reported by Falck et al. (21), even for an exceedingly sensitive substrate, and 10–30 mg of each inverted EDP was readily obtained by this method.

Fig. 3.

Representative chiral HPLC traces (see Materials and Methods) showing inversion of 16(S),17(R)-2b. Enantiopure 16(S),17(R)-2b produced by BM3 (F87V) (A); artificial mixture of 2b enantiomers before and after inversion (B); and 16(R),17(S)-2b produced by chemical inversion (C). See Materials and Methods. The two peaks at ca. 3 min in each trace correspond to the void time of the column.

Fig. 4.

Representative chiral HPLC traces (see Materials and Methods) showing inversion of 19(S),20(R)-2a. Enantiopure 19(S),20(R)-2a produced by WT-BM3 (A); artificial mixture of 2a before and after inversion (B); and 19(R),20(S)-2a produced by chemical inversion (C). See Materials and Methods. The two peaks at ca. 3 min correspond to the void time of the column.

Inversion of 19(S),20(R)-3a.

|

Scheme 4. |

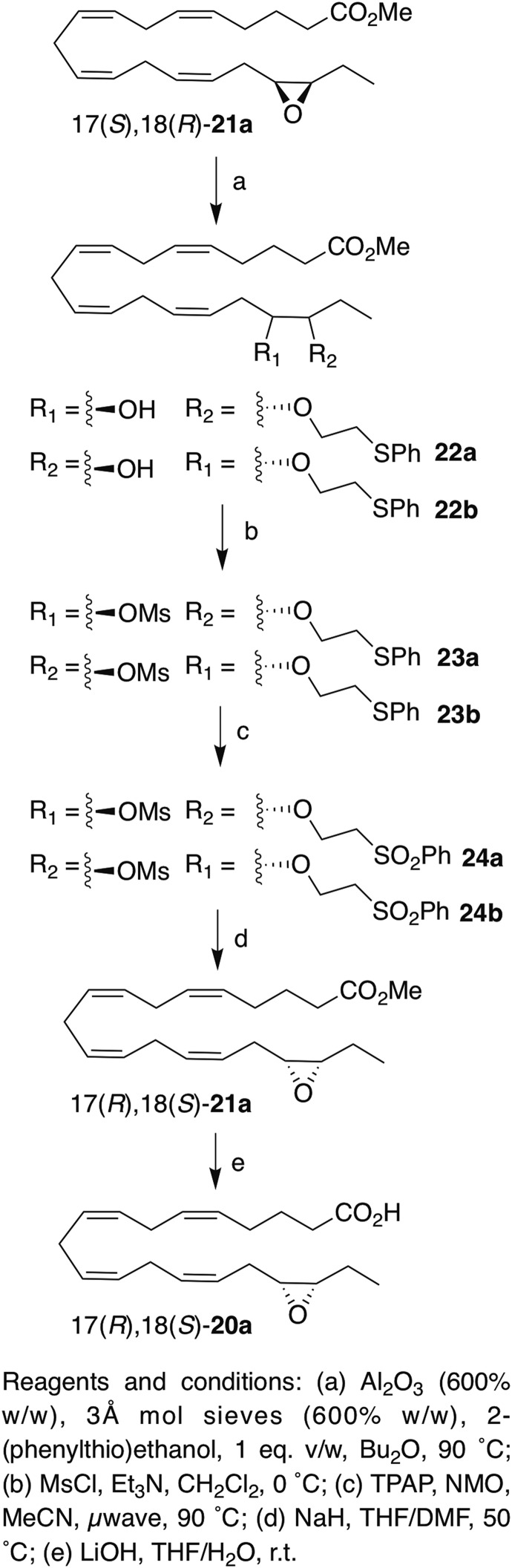

To expand the scope of our process, we also applied the chemical inversion method to the EEQ ester 17(S),18(R)-21a (Scheme 5; see supplemental data for more details). Opening of the epoxide yielded adducts 22a and 22b, which were converted to the mesylates 23a and 32b. As observed with the EDP-derived mesylates, some material was lost during the oxidation to the sulfones (because of decomposition), but 24a/24b were obtained in slightly higher yield than 14a/14b and 18a/18b (64% vs. 60% and 51%, respectively), and the reoxidation of the intermediate sulfoxide was slightly faster (being complete in 30 min instead of 40 min for 18a/18b), suggesting that the sluggishness and decomposition were enhanced by the presence of extra olefins. Conversion of 18a/18b to 17(R),18(S)-21a proceeded smoothly in under 2 h; the inverted EEQ was obtained in 30% overall yield. Like with EDP, both polarimetry of the ester and chiral HPLC of the free acid (supplemental Fig. S9C) confirmed a very clean stereochemical inversion in this case as well (>99:1 er, >98% ee); the chemical purity of the inverted epoxide (supplemental Fig. S10) was also very high (>98%). Over 20 mg of the inverted EEQ was produced by this method.

Inversion of 17(S),18(R)-21a.

|

Scheme 5. |

DISCUSSION

Because of both our ongoing studies with PUFAs and the many reported bioactivities of DHA and EDPs, we sought an operationally simple and cost-effective method to access both enantiomers of two EDP regioisomers, 16,17- and 19,20-EDP, without recourse to total synthesis or chiral separations. Enzymatic synthesis has become a popular method to access both single enantiomers of molecules and compounds that are otherwise difficult to prepare by conventional synthetic means and have been used successfully in esterifications (40), glycosylations (41), aldol reactions (42), and kinetic resolutions (43) and have even been used on an industrial scale (44). Enzymes are operationally simple to use, have fast reaction times, use mild conditions, and are environmentally benign (aqueous reactions; lack of heavy metal catalysts or toxic solvents). Many investigations utilizing FAs as substrates for enzymatic reactions have also been performed. For example, FAs have been epoxidized with combinations of hydrogen peroxide and lipases (45), and enzymes have also been used to prepare FA diols and hydroxy FAs (which are being investigated for their biological properties as well as their uses in industrial and materials applications) (46). The bacterial cytochrome BM3 has previously been used to prepare drug metabolites (47) and natural products (48), and many mutants have been engineered to perform specific oxidation processes or for enhanced substrate recognition, solvent tolerance, and high turnover number (49, 50). BM3 and its various mutants produce different FA metabolites including hydroxy FAs and epoxides, and the selectivity of WT-BM3 and its mutants has been reported (21–24). Encouraged by these reports, we have optimized and scaled up the enzymatic epoxidation of DHA to prepare the enantiopure EDPs 19(S),20(R)-2a and 16(S),17(R)-2b on a larger scale.

Several studies have been conducted on the conditions under which BM3 can be used for enzymatic synthesis. It was demonstrated that the cosolvent concentration greatly affects the enzyme activity, especially for the F87V mutant (47). Therefore, we limited the amount of DMSO, which is the most compatible solvent with this enzyme, to 1%. Because the enzyme was stored in glycerol at −78°C following purification, we limited the maximum amount of cosolvent to 2%. Additionally, it has been shown that preincubation of BM3 with NADPH in the absence of substrate arrests the interdomain electron transfer (which is necessary for catalysis) and thus inhibits the enzyme activity (25, 51–53). Therefore, the NADPH was added last to start the enzymatic reaction. It is also reported that the Kd for the dimerization of BM3 monomers is 1.1 ± 0.2 nM, with maximum activity achieved beyond ∼5 nM (54). The optimization was therefore started at an enzyme concentration of 5 nM. Based on the small set of optimizations, we identified conditions that produced a maximum level of EDPs in only 15 min without using excess NADPH or enzyme (20 nM BM3, 400 µM DHA, and 1.0 equiv. of NADPH), although there was no negative impact if excess enzyme was used (at least in the case of 4; see supplemental Table S7). The optimization also revealed that it is likely that the best DHA (substrate):BM3 ratio is ≤20,000:1. As the solubility of DHA in the reaction buffer was low (≤125 µM; see supplemental Fig. S8), we did not exceed 400 µM, as a significant emulsion began to form in the reaction mixture at this concentration.

The scale-up enzymatic synthesis was conducted with the optimized conditions, and a comparable overall yield of epoxides (47%) was obtained from DHA. The major fraction obtained from WT-BM3 epoxidation was 19(S),20(R)-2a, whereas a greater percentage of 16(S),17(R)-2b was formed when the BM3 (F87V) mutant was used. The mutant result is consistent with both prior published results for DHA (23) and reports that a greater fraction of the penultimate double bond is also oxidized in 19 (24) when this mutant is used. The crystal structure of WT-BM3 (55) reveals that the substrate binding site resembles a funnel, with a large opening and a narrow binding pocket close to the heme center. Phe87 is in close contact with the heme; therefore, the smaller valine residue of BM3 (F87V) results in a pocket that can accommodate larger substrates, and this mutant is reported as a “promiscuous” enzyme. This larger binding site, unhindered by the bulky Phe87 (31, 56), allows the other regioisomer to form because of the better spatial orientation of the alternate reactive intermediates formed near the catalytic (reduced) heme (57). Interestingly, although the enantiomeric ratio of the 19(S),20(R)-2a formed with the F87V mutant was only 89:11 (78% ee), that of the 16(S),17(R)-2b was >99:1 (er). One possible explanation is that the 16,17-position of DHA is analogous to the 14,15-position of 4 (the epoxidation of which is highly enantioselective with this mutant) and fits snugly in the enzyme, whereas the F87V mutation opens the binding pocket close to the heme, and thus the enzyme could accommodate multiple active intermediates or binding orientations during the formation of 19,20-EDP, resulting in a loss of enantioselectivity (56). The obtained results also indicate that different enzymes may be utilized for preparative purposes depending on which enantiopure regioisomer is desired. Our optimized enzymatic synthesis is extremely cost-effective. Currently, racemic 2a is offered by a commercial source for $528 per 0.5 mg (58). The use of 1 g NADPH (approximately $500) for enzymatic epoxidation yields more than 250-fold that amount in enantiopure form without requiring multistep synthesis. Promisingly, improved yields of the EET ester 14(S),15(R)-6 were also obtained when the optimized conditions were applied to 4. FA 19 could also be epoxidized using this procedure, yielding 56% yield of epoxides. The monoepoxide fraction was predominantly 17(S),18(R)-20a, with only ca. 7% of the 14,15-isomer 20b present. The 17(S),18(R)-20a was obtained in very high enantiopurity; although we did not measure the enantiopurity of 20b because of the small amounts obtained, the obtained material has the same negative optical rotation as the (S,R)-EDP esters produced by the WT enzyme, and the F87V mutant is reported to produce 14(S),15(R)-20b exclusively (31), so it is likely that our 20b is the same enantiomer. Interestingly, in addition to the di-epoxide 2c, other oxygenation products (including 19-HEPE and other inseparable products that we could not identify) were obtained. It is possible that, upon scale-up, WT-BM3 does not exclusively epoxidize 19, but it is more likely that the conditions we optimized for DHA are not perfectly optimized for 19. Indeed, it is reported that when enzymatically epoxidizing FAs, using a longer incubation time (or a suboptimal concentration of FA or enzyme) can result in degradation of the epoxides or mixtures of side products, including those formed from both epoxidation and hydroxylation (23).

We also have developed a method for chemically accessing the antipodes [the (R,S) epoxides] of the epoxides produced by the enzyme. Both enantiomers of 3a have been previously accessed by enzymatic resolution of 19,20-EDP bromohydrins, followed by ring closure (59). Total synthesis has been used to prepare EEQs and EETs (20, 60, 61), but not EDPs. Instead, we sought to simply convert the (S,R)-EDPs to (R,S)-EDPs by direct inversion of the stereochemistry at the epoxide. Several methods for epoxide inversion are reported in the literature, utilizing addition of an alcohol bearing a latent leaving group to the epoxide, followed by conversion of the free alcohol to mesylate or tosylate, followed by elimination of the latent leaving group and concomitant SN2 displacement of the sulfonate to produce the inverted epoxide (21). Cesium propionate (33, 62) is reported to cleave epoxides, but in our hands, only racemized the enantiopure 19(S),20(R)-3a. It was discovered that propionate migration occurs rapidly following epoxide cleavage (including at room temperature), which erodes the stereochemistry (see supplemental Scheme S1). Although acyl migration has not been previously reported when using cesium propionate, caution should be exercised when inverting epoxide stereochemistry by these means, as other manipulations involving monoacylated diols and base can cause acyl migration (63). Other epoxide inversion methods have utilized benzyl alcohol as the epoxide-opening nucleophile (64), which is then removed by hydrogenation during reclosure of the epoxide, but this method is, intuitively, not appropriate for PUFAs, as the hydrogenation could reduce the double bonds. Although many catalysts and conditions failed to open epoxy fatty esters (model substrates or EDPs; see supplemental Table S4), optimizations with a model substrate based on methyl linoleate revealed that a modification of a procedure published for 14,15-EET 6 (21) could be effectively used for EDPs and EEQs. Aided by the Lewis acidity of alumina, the epoxide is opened by 2-(phenylthio)ethanol. The resulting free alcohol is then mesylated, and the thioether moiety is oxidized to the sulfone with TPAP. Treatment with base results in elimination of phenyl vinyl sulfone, followed by intramolecular SN2 displacement of the mesylate by the liberated alkoxide. Although giving similar yields and complete stereochemical inversion, our method has some advantages over Falck’s method, namely, that the different mesylation, oxidation, and elimination conditions significantly shorten the overall reaction time needed for the inversion (from >60 h to <25 h) and yield fewer by-products, and its high tolerance of very sensitive substrates (EEQ and EDP) demonstrates its likely applicability to a wide variety of epoxy FA derivatives.

It is worth noting that, because of the presence of their multiple double bonds, EDPs, EEQs, and EETs are sensitive compounds and may slowly darken and polymerize upon exposure to light, heat, or oxygen. Therefore, these pure epoxy FAs should be stored at −80°C or lower under an argon or nitrogen headspace. They are most stable as a solution in absolute ethanol, and they remain stable in solution for up to 1 year (without loss of purity by LC/MS, which is the best method for assaying purity and stability of these epoxides).

In conclusion, we have optimized the enzymatic synthesis of EDPs from DHA using the versatile P450 enzyme BM3. This procedure is simple and cost-effective, and allows for the synthesis of enantiopure EDPs (or EEQs or EETs) on a preparative scale (>100 mg). A four-step chemical inversion sequence allowed access to the enantiomers (10–30 mg) not produced by the enzyme. We plan to report some of the unique biological activities of EDP enantiomers in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank F. Ann Walker for the generous gift of the plasmid containing WT-BM3. The authors also thank Dr. Tony Schilmiller of the MSU Mass Spectrometry and Metabolomics Facility for assistance with HRMS data acquisition, Drs. Edmund Ellsworth and Bilal Aleiwi of the MSU Medicinal Chemistry Core for use of their microwave reactor, and Xinliang Ding for assistance with polarimetry.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AA

- arachidonic acid

- Bu2O

- dibutyl ether

- DMF

- N,N-dimethylformamide

- EDP

- epoxydocosapentaenoic acid (or epoxydocosapentaenoate)

- ee

- enantiomeric excess

- EEQ

- epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (or epoxyeicosatetraenoate)

- EET

- epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (or epoxyeicosatrienoate)

- er

- enantiomeric ratio

- equiv.

- equivalent

- EtOAc

- ethyl acetate

- G6PDH

- glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HRMS

- high-resolution mass spectrometry

- MeCN

- acetonitrile

- MeOH

- methanol

- NMO

- N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide

- P450

- cytochrome P450 enzyme

- sat. aq.

- saturated aqueous

- THF

- tetrahydrofuran

- TPAP

- tetra-n-propylammonium perruthenate

This work is funded by National Institutes of Health Grant R00 ES024806 and startup funds from Michigan State University. J.Y. is supported by Mars Research Grant 211703442, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant P42 ES004699, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant U54 NS079292. The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morisseau C., Inceoglu B., Schmelzer K., Tsai H. J., Jinks S. L., Hegedus C. M., and Hammock B. D.. 2010. Naturally occurring mono epoxides of EPA and DHA are bioactive antihyperalgesic lipids. J. Lipid Res. 51: 3481–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang G., Kodani S., and Hammock B. D.. 2014. Stabilized epoxygenated fatty acids regulate inflammation, pain, angiogenesis, and cancer. Prog. Lipid Res. 53: 108–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell W. B., Gebremedhin D., Pratt P. F., and Harder D. R.. 1996. Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ. Res. 78: 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulu A., Lee K., Miyabe C., Yang J., Hammock B. G., Dong H., and Hammock B. D.. 2014. An omega-3 epoxide of docosahexaenoic acid lowers blood pressure in angiotensin-II-dependent hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 64: 87–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye D., Zhang D., Oltman C., Dellsperger K., Lee H. C., and VanRollins M.. 2002. Cytochrome p-450 epoxygenase metabolites of docosahexaenoate potently dilate coronary arterioles by activating large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 303: 768–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imig J. D. 2015. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, hypertension, and kidney injury. Hypertension. 65: 476–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capozzi M. E., Hammer S. S., McCollum G. W., and Penn J. S.. 2016. Epoxygenated fatty acids inhibit retinal vascular inflammation. Sci. Rep. 6: 39211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner K., Lee K. S., Yang J., and Hammock B. D.. 2017. Epoxy fatty acids mediate analgesia in murine diabetic neuropathy. Eur. J. Pain. 21: 456–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner K., Vito S., Inceoglu B., and Hammock B. D.. 2014. The role of long chain fatty acids and their epoxide metabolites in nociceptive signaling. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 113–115: 2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang G., Panigrahy D., Mahakian L. M., Yang J., Liu J. Y., Lee K. S., Wettersten H. I., Ulu A., Hu X., Tam S., et al. 2013. Epoxy metabolites of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) inhibit angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110: 6530–6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross G. J., Hsu A., Falck J. R., and Nithipatikom K.. 2007. Mechanisms by which epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) elicit cardioprotection in rat hearts. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 42: 687–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang L., Mäki-Petäjä K., Cheriyan J., McEniery C., and Wilkinson I. B.. 2015. The role of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the cardiovascular system. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 80: 28–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold C., Markovic M., Blossey K., Wallukat G., Fischer R., Dechend R., Konkel A., von Schacky C., Luft F. C., Muller D. N., et al. 2010. Arachidonic acid-metabolizing cytochrome P450 enzymes are targets of {omega}-3 fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 32720–32733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou A. P., Fleming J. T., Falck J. R., Jacobs E. R., Gebremedhin D., Harder D. R., and Roman R. J.. 1996. Stereospecific effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on renal vascular tone and K(+)-channel activity. Am. J. Physiol. 270: F822–F832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauterbach B., Barbosa-Sicard E., Wang M. H., Honeck H., Kärgel E., Theuer J., Schwartzman M. L., Haller J., Luft F. C., Gollasch M., et al. 2002. Cytochrome P450-dependent eicosapentaenoic acid metabolites are novel BK channel activators. Hypertension. 39: 609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shearer G. C., Harris W. S., Pederson T. L., and Newman J. W.. 2010. Detection of omega-3 oxylipins in human plasma in response to treatment with omega-3 acid ethyl esters. J. Lipid Res. 51: 2074–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mozaffarian D., and Wu J. H.. 2011. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58: 2047–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke T., Black T., Stussman B., Barnes P., and Nahin R.. 2015. Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults: United States, 2002–2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan M. A. and Wood P.. 2012. Method for the synthesis of DHA. Patent application WO2012126088A1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nanba Y., Shinohara R., Morita M., and Kobayashi Y.. 2017. Stereoselective synthesis of 17,18-epoxy derivative of EPA and stereoisomers of isoleukotoxin diol by ring-opening of TMS-substituted epoxide with dimsyl sodium. Org. Biomol. Chem. 15: 8614–8626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falck J. R., Reddy Y. K., Haines D. C., Reddy K. M., Krishna U. M., Graham S., Murray B., and Peterson J. A.. 2001. Practical, enantiospecific syntheses of 14,15-EET and leukotoxin B (vernolic acid). Tetrahedron Lett. 42: 4131–4133. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celik A., Sperandio D., Speight R. E., and Turner N. J.. 2005. Enantioselective epoxidation of linolenic acid catalysed by cytochrome P450(BM3) from Bacillus megaterium. Org. Biomol. Chem. 3: 2688–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capdevila J. H., Wei S., Helvig C., Falck J. R., Belosludtsev Y., Truan G., Graham-Lorence S. E., and Peterson J. A.. 1996. The highly stereoselective oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by cytochrome P450BM-3. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 22663–22671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucas D., Goulitquer S., Marienhagen J., Fer M., Dreano Y., Schwaneberg U., Amet Y., and Corcos L.. 2010. Stereoselective epoxidation of the last double bond of polyunsaturated fatty acids by human cytochromes P450. J. Lipid Res. 51: 1125–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matson R. S., Hare R. S., and Fulco A. J.. 1977. Characteristics of a cytochrome P-450-dependent fatty acid ω-2 hydroxylase from Bacillus megaterium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 487: 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murataliev M. B., Trinh L. N., Moser L. V., Bates R. B., Feyereisen R., and Walker F. A.. 2004. Chimeragenesis of the fatty acid binding site of cytochrome P450BM3. Replacement of residues 73–84 with the homologous residues from the insect cytochrome P450 CYP4C7. Biochemistry. 43: 1771–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wen L. P., and Fulco A. J.. 1987. Cloning of the gene encoding a catalytically self-sufficient cytochrome P-450 fatty acid monooxygenase induced by barbiturates in Bacillus megaterium and its functional expression and regulation in heterologous (Escherichia coli) and homologous (Bacillus megaterium) hosts. J. Biol. Chem. 262: 6676–6682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guengerich F. P., Martin M. V., Sohl C. D., and Cheng Q.. 2009. Measurement of cytochrome P450 and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Nat. Protoc. 4: 1245–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noble M. A., Miles C. S., Chapman S. K., Lysek D. A., MacKay A. C., Reid G. A., Hanzlik R. P., and Munro A. W.. 1999. Roles of key active-site residues in flavocytochrome P450 BM3. Biochem. J. 339: 371–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee K. S., Morisseau C., Yang J., Wang P., Hwang S. H., and Hammock B. D.. 2013. Forster resonance energy transfer competitive displacement assay for human soluble epoxide hydrolase. Anal. Biochem. 434: 259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham-Lorence S., Truan G., Peterson J. A., Falck J. R., Wei S., Helvig C., and Capdevila J. H.. 1997. An active site substitution, F87V, converts cytochrome P450 BM-3 into a regio- and stereoselective (14S, 15R)-arachidonic acid epoxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 1127–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X., Saba T., Yiu H. H. P., Howe R. F., Anderson J. A., and Shi J.. 2017. Cofactor NAD(P)H regeneration inspired by heterogeneous pathways. Chem. 2: P621–P654. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arbelo D. O., and Prieto J. A.. 2002. Cesium propionate as an epoxide cleavage and inversion reagent. Tetrahedron Lett. 43: 4111–4114. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barluenga J., Vázquez-Villa H., Ballasteros A., and González J. M.. 2002. Copper(II) tetrafluoroborate catalyzed ring-opening reaction of epoxides with alcohols at room temperature. Org. Lett. 4: 2817–2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Likhar P. R., Kumar M. P., and Bandyopadhyay A. K.. 2001. Ytterbium trifluoromethanesulfonate Yb(OTf)3: an efficient, reusable catalyst for highly selective formation of beta-alkoxy alcohols via ring-opening of 1,2-epoxides with alcohols. Synlett. 6: 836–838. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalpozzo R., Nardi M., Oliverio M., Paonessa R., and Procopio A.. 2009. Erbium(III) triflate is a highly efficient catalyst for the synthesis of beta-alkoxy alcohols, 1, 2-diols, and beta-hydroxy sulfides by ring opening of epoxides. Synthesis. 20: 3433–3438. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams D. B., and Lawton M.. 2005. Aluminum triflate: a remarkable Lewis acid catalyst for the ring opening of epoxides by alcohols. Org. Biomol. Chem. 3: 3269–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leitão A. J. L., Salvador J. A. R., Pinto R. M. A., and Luísa Sá e Melo M.. 2008. Hydrazine sulphate: a cheap and efficient catalyst for the regioselective ring-opening of epoxides. A metal-free procedure for the preparation of beta-alkoxy alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 49: 1694–1697. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Posner G. H., and Rogers D. Z.. 1977. Organic reactions at alumina surfaces. Mild and selective opening of epoxides by alcohols, thiols, benzeneselenol, amines, and acetic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99: 8208–8214. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stergiou P. Y., Foukis A., Filippou M., Koukoritaki M., Parapouli M., Theodorou L. G., Hatziloukas E., Afendra A., Pandey A., and Papamichael E. M.. 2013. Advances in lipase-catalyzed esterification reactions. Biotechnol. Adv. 31: 1846–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh T. J., Kim D. H., Kang S. Y., Yamaguchi T., and Sohng J. K.. 2011. Enzymatic synthesis of vancomycin derivatives using galactosyltransferase and sialyltransferase. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 64: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bednarski M. D., Simon E. S., Bischofberger N., Fessner W. D., Kim M. J., Lees W., Saito T., Waldmann H., and Whitesides G. M.. 1989. Rabbit muscle aldolase as a catalyst in organic synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111: 627–635. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juma W. P., Chhiba V., Brady D., and Bode M. L.. 2017. Enzymatic kinetic resolution of Morita-Baylis-Hillman acetates. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 28: 1169–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Julsing M. K., Cornelissen S., Bühler B., and Schmid A.. 2008. Heme-iron oxygenases: powerful industrial biocatalysts? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12: 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Åkerman C. O. C., Camocho S., Adlercreutz D., Mattiasson B., and Hatti-Kaul R.. 2005. Chemo-enzymatic epoxidation of linoleic acid: parameters influencing the reaction. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 107: 864–870. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim K. R., and Oh D. K.. 2013. Production of hydroxy fatty acids by microbial fatty acid-hydroxylation enzymes. Biotechnol. Adv. 31: 1473–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Nardo G., and Gilardi G.. 2012. Optimization of the bacterial cytochrome P450 BM3 system for the production of human drug metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13: 15901–15924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dietrich J. A., Yoshikuni Y., Fisher K. J., Woolard F. X., Ockey D., McPhee D. J., Renninger N. S., Chang M. C., Baker D., and Keasling J. D.. 2009. A novel semi-biosynthetic route for artemisinin production using engineered substrate-promiscuous P450BM3. ACS Chem. Biol. 4: 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jung S. T., Lauchli R., and Arnold F. H.. 2011. Cytochrome P450: taming a wild type enzyme. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22: 809–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong T. S., Arnold F. H., and Schwaneberg U.. 2004. Laboratory evolution of cytochrome P450 BM-3 for organic cosolvents. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 85: 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruettinger R. T., and Fulco A. J.. 1981. Epoxidation of unsaturated fatty acids by a soluble cytochrome P-450-dependent system from Bacillus megaterium. J. Biol. Chem. 256: 5728–5734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Narhi L. O., and Fulco A. J.. 1986. Characterization of a catalytically self-sufficient 119,000-dalton cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase induced by barbiturates in Bacillus megaterium. J. Biol. Chem. 261: 7160–7169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Girvan H. M., Dunford A. J., Neeli R., Ekanem I. S., Waltham T. N., Joyce M. G., Leys D., Curtis R. A., Williams P., Fisher K., et al. 2011. Flavocytochrome P450 BM3 mutant W1046A is a NADH-dependent fatty acid hydroxylase: implications for the mechanism of electron transfer in the P450 BM3 dimer. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 507: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neeli R., Girvan H. M., Lawrence A., Warren M. J., Leys D., Scrutton N. S., and Munro A. W.. 2005. The dimeric form of flavocytochrome P450 BM3 is catalytically functional as a fatty acid hydroxylase. FEBS Lett. 579: 5582–5588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravichandran K. G., Boddupalli S. S., Haserman C. A., Peterson J. A., and Deisenhofer J.. 1993. Crystal structure of hemoprotein domain of P450BM-3, a prototype for microsomal P450’s. Science. 261: 731–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geronimo I., Denning C. A., Rogers W. E., Othman T., Huxford T., Heidary D. K., Glazer E. C., and Payne C. M.. 2016. Effect of mutation and substrate binding on the stability of cytochrome P450BM3 variants. Biochemistry. 55: 3594–3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oliver C. F., Modi S., Sutcliffe M. J., Primrose W. U., Lian L. Y., and Roberts G C.. 1997. A single mutation in cytochrome P450 BM3 changes substrate orientation in a catalytic intermediate and the regiospecificity of hydroxylation. Biochemistry. 36: 1567–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cayman Chemical. 19,20-EpDPA. Accessed April 15, 2018 at https://www.caymanchem.com/product/10175.

- 59.Kato T., Ishimatu T., Aikawa A., Taniguchi K., Kurahashi T., and Nakai T.. 2000. Preparation of the enantiomers of 19-epoxydocosahexaenoic acids and their 4-hydroxy derivatives. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 11: 851–860. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mosset P., Yadagiri P., Lumin S., Capdevila J., and Falck J. R.. 1986. Arachidonate epoxygenase: total synthesis of both enantiomers of 8,9- and 11,12-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 27: 6035–6038. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han X., Crane S. N., and Corey E. J.. 2000. A short catalytic enantioselective synthesis of the vascular anti-inflammatory eicosanoic (11R,12S)-oxidoarachidonic acid. Org. Lett. 2: 3437–3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uyanik M., Ishihara K., and Yamamoto H.. 2005. Biomimetic synthesis of acid-sensitive (-)- and (+)-caparrapi oxides, (-)- and (+)-8-epicaparrapi oxides, and (+)-dysifragin induced by artificial cyclases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 13: 5055–5065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu K. K-C., Nozaki K., and Wong C-H.. 1990. Problems of acyl migration in lipase-catalyzed enantioselective transformation of meso-1,3-diol systems. Biocatalysis. 3: 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oliver J. E., Waters R. M., and Harrison D. J.. 1996. Semiochemicals via epoxide inversion. J. Chem. Ecol. 22: 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.