Abstract

Membrane proteins play vital roles in cellular signaling processes and serve as the most popular drug targets. A key task in studying cellular functions and developing drugs is to measure the binding kinetics of ligands with the membrane proteins. However, this has been a long-standing challenge because one must perform the measurement in a membrane environment to maintain the conformations and functions of the membrane proteins. Here, we report a new method to measure ligand binding kinetics to membrane proteins using self-assembled virion oscillators. Virions of human herpesvirus were used to display human G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) on their viral envelopes. Each virion was then attached to a gold-coated glass surface via a flexible polymer to form an oscillator and driven into oscillation with an alternating electric field. By tracking changes in the oscillation amplitude in real-time with subnanometer precision, the binding kinetics between ligands and GPCRs was measured. We anticipate that this new label-free detection technology can be readily applied to measure small or large ligand binding to any type of membrane proteins and thus contribute to the understanding of cellular functions and screening of drugs.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Membrane proteins relay signals between a cell and its external environment, transport ions and molecules in and out of the cell, and allow the cell to recognize and interact with other cells.1–6 They also constitute the drug targets of >50% of the FDA-approved drugs.7 Understanding these vital cellular functions and screening new drugs require measurement of the binding kinetics between membrane proteins and their ligands or drugs. However, developing such a capability has been challenging because membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to express and purify, while at the same time preserving their functional conformations required for biochemical studies and drug screening.8,9

Even if a membrane protein is successfully purified with its native conformation preserved, it remains challenging to measure its binding kinetics to a ligand, especially small molecule. Traditional detection methods use radiolabeled or fluorescent-labeled ligands. Recently, a backscattering interferometry technology has been developed to study molecular binding, including proteins on unilamellar vesicles.10 These technologies are end-point assays, which provide affinity but not binding kinetics. Measuring binding kinetics is critical for determining drug efficacy, residence time,11,12 and biased agonism,13 and for elucidating ligand−target binding mechanism in drug design.14 Label-free detection technologies have been developed to determine molecular binding kinetics,15–20 but these mass sensitive technologies cannot accurately measure small molecule binding to membrane proteins, particularly for membrane proteins that have low coverage on the sensor surface.

There is a need to develop a detection technology capable of measuring both large and small molecule binding to membrane proteins in their native environment.21,22 We address this need with a virion oscillator detection technology. We displayed human G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in the virus envelopes of herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) using the Virion Display (VirD) technology,23 and then tethered each virion to a gold-coated chip via a flexible polymer linker.24,25 By applying an alternating electric field to the gold surface, the virions were made to oscillate, and the oscillation amplitude was measured with subnanometer precision using a plasmonic imaging technique.24 Upon adding ligands to the chip, the oscillation amplitude changed. This amplitude change is used to determine the binding kinetics of the bound molecule. We showed that the virion oscillator detection technology could detect the binding kinetics of low molecular mass molecules to membrane proteins in real time and applied it to study molecular binding to human GPCRs. The virion oscillator detection technology eliminates the need of extracting and purifying membrane proteins, which alleviates the associated difficulties, and thus provides a label-free and multiplexed detection platform for the binding of ligands to human membrane proteins displayed on virions.

RESULTS

Fabrication and Detection Principle of Virion Oscillators.

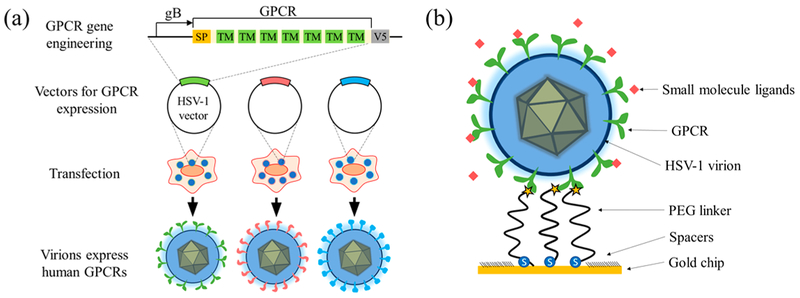

We fabricated virion oscillators by tethering single HSV-1 virions (~185 nm in diameter) to a gold-coated chip via polyethylene glycol (PEG) linkers (63 nm in length) (Figure 1b). Each PEG linker has a thiol group on one end to attach to the gold surface and a N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) moiety on the other end to form a covalent bond to the virions via the primary amines of the viral glycoproteins in the envelopes.

Figure 1.

Integration of Virion Display (VirD) with virion oscillators for studying membrane proteins. (a) Displaying human GPCRs on HSV-1 envelope with VirD. (b) Fabricating virion oscillators. Each virion oscillator consisting of a virion tethered to a gold surface with 63 nm long polyethylene glycol (PEG) linkers. The PEG linker contains a thiol and a N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) on its two ends, where the thiol group binds to the gold surface and the NHS group cross-links the virion via NHS-amine reaction.

By applying an alternating electric field perpendicular to the gold surface, each virion oscillates with amplitude given by (Supporting Information)

| (1) |

where E0 and ƒ are the amplitude and frequency of the alternating electric field, respectively, j is the imaginary unit(), representing 90° phase difference between the applied field and oscillation displacement. μ in eq 1 is the mobility of the virion, which can be expressed as qD/kBT, according to the Einstein relation, where q and D are the effective charge and diffusion coefficient of the virion, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is temperature. Upon ligand binding to the membrane proteins on the viral envelope, the oscillation amplitude changes as the binding changes the mobility (μ) of the virion. For a charged ligand, the binding changes the mobility because it changes the effective charge of the virion (the Einstein relation). For uncharged ligands, the binding can change the surface charge distribution via conformational changes of the membrane proteins, and also the diffusion coefficient. Unlike other label-free detection technologies mentioned above, the virion oscillator detection technology is not based on mass detection, and its sensitivity, thus, does not diminish with the molecular mass of the ligand.

To accurately detect the virion oscillation amplitude, we used a super luminescent emitting diode (SLED) to excite a surface plasmonic wave along the gold surface, and imaged the scattering of the plasmonic wave by the virions with a CCD camera using an inverted optical microscope.26 The plasmonic imaging technique resolves a virion as a bright spot with a parabolic tail, arising from the scattering of the propagating plasmonic wave by the virion (Figure 2b).24,26 Because the amplitude of the plasmonic wave decays exponentially from the gold surface into the solution, the plasmonic imaging intensity (I) is extremely sensitive to the distance between the virion and the surface (z), given by24

| (2) |

where I0 is a constant and l (~200 nm) is the decay constant of the evanescent field. This sensitive dependence is shown in Figure 2c, which displays a few snapshots of the plasmonic image of a single virion during an oscillation cycle. From the image intensity, we determined the oscillation displacement vs time (Figure 2d). The phase difference between the oscillation displacement and the applied electric field is ~97°, which is close to the prediction of 90° by eq 1.

Figure 2.

Detecting ligand binding to membrane proteins with virion oscillators. (a) Virions are tethered to a gold surface via flexible PEG linkers and imaged with a plasmonic microscope. The virions are driven into oscillation with an alternating electric field applied to the gold surface with a three-electrode electrochemical setup, where WE, RE, and CE are the working (the gold chip), quasi-reference (a Ag wire), and counter electrodes (a Pt coil), respectively. Ligands were introduced to bind to the membrane proteins on the virion surfaces with a drug perfusion system. (b) Plasmonic images of several virion oscillators, each showing a parabolic pattern (arising from the scattering of surface plasmonic waves by the virion). A full video of the oscillating virions is provided in Supporting Information. (c) Snapshots of one virion oscillator (marked in (b)) during different phases of an oscillation cycle, where the image intensity change reflects the change in virion−gold chip distance. (d) Virion−gold chip distance or oscillation displacement (red) of the virion oscillator in (c) and applied field (blue) with frequency, ƒ= 5 Hz. (e) Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of virion−gold chip distance (red) showing a pronounced peak at 5 Hz, and the peak amplitude is the oscillation amplitude, where the black line is the control obtained by performing FFT on the virion–gold chip distance without applied electric field.

By performing fast Fourier transform (FFT) on the image intensity (oscillation displacement), we observed a pronounced peak at the frequency of the applied field (Figure 2e, red line). The peak height corresponds to the oscillation amplitude of the virion, which can be determined precisely with an uncertainty of 0.8 nm (Figure 2e, black line). If we assume that the binding is due to a change in the charge, this amplitude uncertainty corresponds to a charge detection limit of 3.1e, where e is the elementary charge (see Discussion). In addition to high sensitivity, the plasmonic imaging method resolves individual virions simultaneously, providing multiplexed detection of binding kinetics of many virions.

Measurement of Ligand Binding to GPCRs Displayed on Virions.

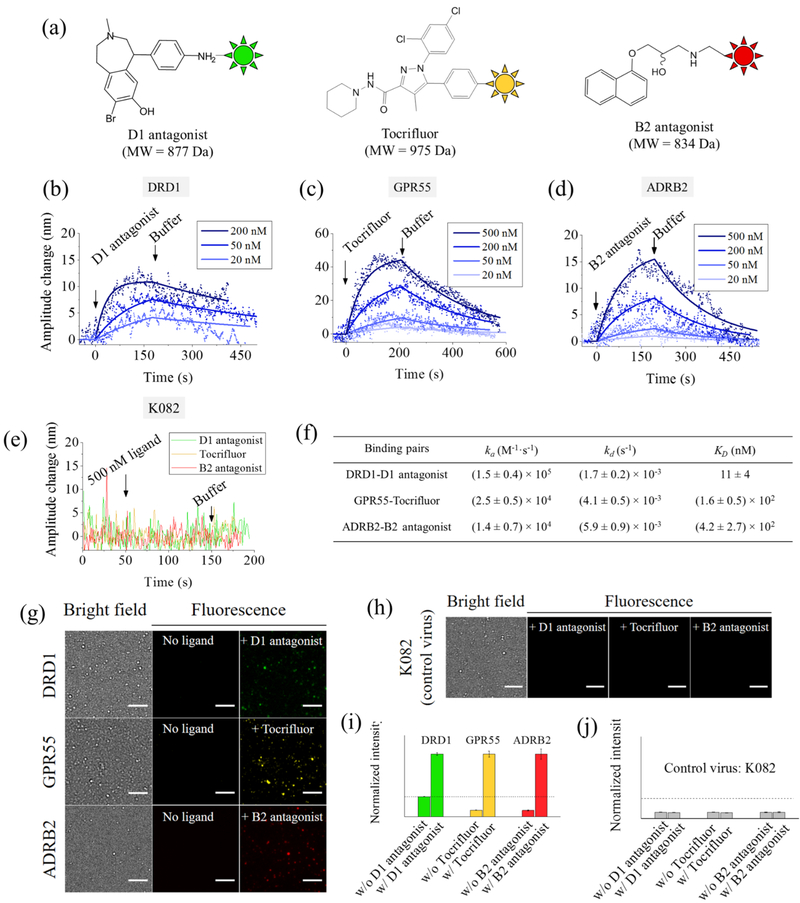

Using the VirD technology, we displayed three human GPCRs, DRD1, GPR55, and ADRB2, on the HSV-1 envelopes, assembled them into virion oscillators, and measured the binding kinetics of three canonical ligands, D1 antagonist, Tocrifluor, and B2 antagonist, that target DRD1, GPR55, and ADRB2, respectively (Figure 3a). To drive the virions into oscillation, we applied a sinusoidal potential with amplitude, 0.4 V, and frequency, 5 Hz, to the gold surface. Initially, we flowed PBS buffer (4 mM) at a rate of 300 μL/min over the virion oscillators (Figure 2a) and recorded the oscillation amplitude to establish a baseline, and then introduced each of the three ligands to allow binding (association) to the corresponding target GPCR on the virions. The binding induced a decrease in the oscillation amplitude in each case, indicating decreased virion mobility, which was further confirmed by electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) measurements (Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

Measuring ligand binding to GPCR with virion oscillators. (a) Chemical structures of D1 antagonist, Tocrifluor, and B2 antagonist. (b–d) Binding kinetic curves (oscillation amplitude vs time) of D1 antagonist−DRD1, Tocrifluor−GPR55, and B2 antagonist−ADRB2 interactions, respectively, where the solid lines are global fitting of the data to the first order kinetics. Each binding curve is an average over at least five individual virions. (e) Control experiments using virion oscillators prepared with K082 virion, showing no binding to any of the ligands. Applied voltage: amplitude = 0.4 V and frequency = 5 Hz. Buffer: 40-fold diluted PBS (4 mM) and pH = 7.4. (f) Kinetic and equilibrium constants of ligand binding to GPCRs. (g) Validation of specific binding with fluorescence detection. Bright field and fluorescence images of virions expressed with different GPCRs obtained before and after adding the corresponding ligands, and the fluorescence images confirm the specific binding of the ligands to the corresponding receptors. Scale bar, 5 μm. (h) Further control experiments to examine nonspecific binding using the K082 virions. None of the three ligands generated observable fluorescence changes, showing no nonspecific binding in the measured binding kinetics shown in (b–d). Scale bar, 5 μm. (i) Fluorescent intensity of virions with DRD1, GPR55, and ADRB2 before and after adding the corresponding ligands. (j) Fluorescence image intensity of K082 virions before and after adding the three ligands. The dashed lines in (i) and (j) indicate background fluorescence levels.

After measuring the association process, we studied the dissociation of the ligands from the GPCRs by flowing PBS buffer over the virion oscillators and observed that the oscillation amplitude returned to prebinding levels. By repeating the measurement at different concentrations of each ligand, we obtained binding curves for D1 antagonist− DRD1, Tocrifluor−GPR55, and B2 antagonist−ADRB2 interactions, respectively (Figure 3b–d). Fitting the binding curves at different concentrations globally with the first order kinetic model led to the determination of the association rate constant, ka, dissociation rate constant kd, and the equilibrium constant KD (Figure 3f). To demonstrate the accuracy of our method, we measured the KD with fluorescence detection, and the results were close to those measured by the virion oscillators (Figure S7, Supporting Information).

To confirm that the changes in the oscillation amplitude associated with the introduction of ligands were not due to nonspecific binding, we used K082, a gB null HSV-1 virion27 with no GPCR displayed on the envelope, as a negative control and measured its binding with each of the three ligands. We did not observe any detectable changes in the oscillation amplitude (Figure 3e), indicating no nonspecific binding of the ligands to HSV-1 virions. As a further validation of the results, we measured the binding of fluorophore-labeled ligands to the virion oscillators with fluorescence imaging. The fluorescence signal increased significantly from the virion oscillators after incubation with the corresponding ligands (Figure 3g,i). The fluorescence intensity of each virion correlated well with the oscillation amplitude change (Figure S3, Supporting Information). We also measured fluorescence before and after introducing the ligands and observed no fluorescence emission from the virions (Figure 3h,j). These fluorescence-imaging experiments confirmed that the binding kinetics measured with the virion oscillator detection technology was indeed a result of the specific binding of each ligand to its corresponding GPCR.

Multiplexed Measurement of Binding Kinetics with Virion Oscillator Detection Technology.

The plasmonic imaging technique can image multiple virions simultaneously, which allows multiplexed measurement of binding kinetics. The multiplexed detection capability is important because it allows one to study the expression heterogeneity of the GPCRs. We analyzed the variability in the measured kinetics of ligand binding to the GPCRs on the virions. Figure 4b plots the binding of Tocrifluor (200 nM) to the corresponding GPCR on the virions, and the corresponding kinetic and equilibrium constants extracted by fitting the binding curves with the first order kinetics model are listed in Figure 4c. Both the binding curves and kinetic constants display large variability (up to 1 order of magnitude differences). To verify the large variation was due to the heterogeneity of virions rather than experimental errors, we measured the kinetic and equilibrium constants using the same virion three times (Figure S8, Supporting Information). The results were close to each other within 10%, much smaller than the observed virion−virion variability. We obtained the equilibrium constants from 41 individual GPR55 virions and plotted the statistics in Figure 4d. The data was fitted with normal distribution, which has 95% prediction interval from 6.3 nM to2.6 μM. In addition to heterogeneity in the kinetic and equilibrium constants, we also observed that the maximum binding signal varies from virion to virion. Large heterogeneity in ligand binding to membrane proteins is known to occur in individual cells due to variability in the local environment of each membrane protein.15,28

Figure 4.

Heterogeneity in the binding kinetics of different virions. (a) Plasmonic image of multiple individual virion oscillators, where the virions contain GPR55 in their envelopes. (b) Binding curves of Tocrifluor (200 nM) to GPR55-virions marked in (a). Fitting of binding curves of virions 1–8 with the first order kinetics model (virions 9–16 could not be fitted well with the simple model, see Figure S5, Supporting Information). Applied voltage: amplitude = 0.4 V and frequency = 5 Hz. Buffer: 40-fold diluted PBS (4 mM) with pH = 7.4. (c) Variability in the kinetic and equilibrium constants of Tocrifluor binding to multiple single GPR55 virions. (d) Distribution of KD observed from 41 GPR55 virions, where the red curve is Gaussian fitting to the data (showing 95% prediction interval between 6.3 nM to 2.6 μM).

DISCUSSION

The detection limit of the virion oscillator detection platform is determined by the noise level in the oscillation amplitude, which is ~0.8 nm with the present setup. Each virion has an average ~1000 GPCR molecules, and binding of the ligand, Tocrifluor, to the GPR55 receptors led to an amplitude change of ~50 nm. The corresponding detection limit is ~16 Tocrifluor molecules per virion. Similarly, we estimated the detection limits of other ligands, which are ~67 D1 antagonist and ~47 B2 antagonist, respectively.

In addition to binding kinetics, the virion oscillator detection technology also allows the measurements of mobility and charge changes associated with molecular binding to its target on each virion. According to eq 1, we can determine mobility (μ) if the field, E0, is known. We obtained E0 with E0 = J/σ, where J is the current density measured during experiment and σ is the conductivity of the solution measured with Zetasizer Nano (Malvern Instruments). We found that μ = −1.64 × 10−8 m2/(V·s), −1.53 × 10−8 m2/(V·s), and −1.75 × 10−8 m2/(V·s) per virion for virions displayed with DRD1, GPR55, and ADRB2, respectively. The mobility was consistent with those measured with ELS in both polarity and amplitude (Supporting Information). From the mobility values, we can determine the charge (q) with the Einstein relation, μ = qD/kBT, if the diffusion coefficient (D) is known. D is given by the Stokes−Einstein equation

| (3) |

where η is the solution viscosity and a is the virion radius. Knowing η (Supporting Information) and a, we determined the charge changes associated with molecular binding using the Einstein relation and eq 3. The average initial charges of the GPR55, DRD1, and ADRB2 virions were −252e, −271e, and −290e, respectively. Binding of the ligands to the virions changed the corresponding charges by +194e, +44e, and +75e, respectively. The above analysis assumes that the diffusion coefficient (solution viscosity and virion radius) did not change with the ligand binding. To validate this assumption, we estimated changes in the viscosity and effective radius of the virions, which were less than 0.5% and ~1 nm,29 respectively; both are insignificant compared to large measured changes in mobility. We also anticipate that the binding of large ligands such as antibodies can lead to a larger change in virion viscosity and radius, making the diffusion coefficient change more significant than charge change (Supporting Information).

In conclusion, we have developed a virion oscillator detection technology to overcome the long-standing difficulty of studying binding kinetics between a ligand and its membrane protein receptor. In this study, human GPCRs with seven transmembrane domains were displayed on HSV-1 membrane envelopes, and these receptors were displayed in their native environment without the need of extraction and purification. Unlike traditional label-free detection technologies, the virion oscillator detection technology does not rely on mass changes, making it highly suitable for detecting binding to ligands of any sizes in a real-time fashion. Using this new technology, we have obtained the binding kinetics of ligands to human GPCRs and demonstrated multiplexed detection capability. Although binding kinetics of multiple viral particles could be measured simultaneously, only one kind of virion-displayed GPCR can be studied at the moment because of the small detection field. This limitation, however, can be overcome in the future by transforming the current device into a microarray-based platform and by changing the optical imaging system to a prism-based device. For diagnostics, detecting of biomarkers in complex fluids rather than well-defined buffers will be necessary, which is ultimately determined by the specificity of ligand (biomarker) binding to the receptors on the virions. We anticipate that our virion oscillator detection technology can be readily applied to measure binding kinetics and screen for both large and small molecule drugs for any type of membrane proteins in a high-throughput fashion.

METHODS

Materials.

HS-PEG-NHS (MW = 10 kDa) was purchased from Nanocs. Dithiolalkanearomatic PEG6-COOH was purchased from Sensopath Technologies. DRD1, GPR55, and ADRB2 HSV-1 virions were engineered using the VirD technology. D1 antagonist and B2 antagonist (CA200773 and CA200656) were purchased from Hellobio, and Tocrifluor was purchased from Tocris. Other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich. Deionized (DI) water with resistivity of18.2 MΩ/cm, filtrated with 0.45 μm filter, was used in all the experiments.

Production of HSV-1 Virions Incorporating Human GPCRs.

The genes encoding the human GPCRs were cloned into the HSV-1 genome using the Gateway (Invitrogen) method. Each GPCR was expressed under the control of the UL27 (glycoprotein B) gene promoter, and the expressed polypeptide contains a C-terminal V5 epitope tag. To produce virions incorporating GPCRs, we infected Vero cells (30 × 107 cells) at a multiplicity of infection of five plaque forming units/cell. The extracellular medium of these infected cells was collected 48 h after infection, which was then purified and concentrated via centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion. The final virion pellets were resuspended in PBS containing 30% glycerol and stored at −80 °C before use. Incorporation of the GPCR molecule in the virion was confirmed by immunoblots using anti-V5 antibody (data not shown).

Fabrication of Virion Oscillators.

The virions were incubated with HS-PEG-NHS at 1:5 ratio in 1× PBS at 4 °C overnight to form a virion−PEG complex, which was diluted to 104 virions/μL. One hundred microliters of virion−PEG complex was then applied to a gold chip (glass cover slide coated with 47 nm gold) and incubated for 20 min to allow assembly of the virion oscillators on the gold chip. The gold chip was then rinsed with 1× PBS, followed by incubation in 15 nM dithiolalkanearomatic PEG6-COOH overnight to passivate the exposed gold area. The gold chip coated with the virion oscillators was kept wet and stored at 4 °C during the modification.

Experimental Setup.

The plasmonic imaging setup was an inverted microscope (Olympus IX-70 with a 60× (NA 1.49) oil immersion objective). A fiber-coupled superluminescent light emitting diode (SLED, QSDM-68002, Qphotonics) with wavelength 680 nm was used as light source to excite surface plasmons on the gold chip. The plasmonic images were recorded by a CCD camera (Pike F-032B, Allied Vision) at 106.5 frames per second. A sinusoidal potential was applied to the gold chip with a potentiostat (AFCBP1, Pine Instrument Company) and a function generator (33521A, Agilent) using the standard three-electrode setup (with the gold chip as the working electrode, a Ag wire as the quasi-reference electrode, and a Pt coil as the counter electrode). A USB data acquisition card (NI USB-6251, National Instruments) was used to record the time stamp of the images from the camera in order to synchronize plasmonic imaging with electrical measurement.

Signal Processing.

After recording the images, a region of interest (ROI) was selected on each virion (with the parabolic tail), and the mean intensity within the ROI was calculated as the plasmonic intensity of the virion. An adjacent region with the same size was selected as the reference region, and its intensity was used to remove common noise from the ROI. The distance between the virion and gold surface was determined from the plasmonic imaging intensity of the virion using eq 2. Then the oscillation amplitude was obtained in every second using FFT.24 More details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Fluorescence Detection.

The glass slide was cleaned with ethanol and DI water twice, and a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) sample cell was mounted on the slide to hold sample solution. One μL of GPCR-expressing virion solution (106 virions/μL) mixed with 100 μL of 1× PBS was added to the solution cell and incubated for 20 min to allow virions to attach to the glass slide, and then the glass slide was rinsed with 1× PBS to remove unattached virions. Ligands were added to the solution cell to reach a concentration of 200 nM and incubated with the virions for 30 min. The glass slide was then rinsed with 1× PBS twice to remove excess ligand molecules and nonspecifically bound molecules. The excitation and emission wavelengths were 488 and 550 nm for D1 antagonist, 543 and 590 nm for Tocrifluor, and 633 and 650 nm for B2 antagonist, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank National Institutes of Health (R33CA202834, 1R01GM107165, 1R44GM106579, 1R44GM126720, and R33CA186790 (to H.Z./P.J.D.)) for financial support.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b07461.

Additional experimental details and supporting figures (PDF)

Oscillation video (AVI)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Tait SWG; Green DR Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lemmon MA; Schlessinger J Cell 2010, 141 (7), 1117–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Clapham DE Cell 2007, 131 (6), 1047–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Casey JR; Grinstein S; Orlowski J Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Südhof TC; Rothman JE Science 2009, 323 (5913), 474–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).The International Transporter, C.. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 9 (3), 215–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Santos R; Ursu O; Gaulton A; Bento AP; Donadi RS; Bologa CG; Karlsson A; Al-Lazikani B; Hersey A; Oprea TI; Overington JP Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2017, 16 (1), 19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Seddon AM; Curnow P; Booth PJ Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2004, 1666 (1–2), 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lee AG Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2003, 1612 (1), 1–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Baksh MM; Kussrow AK; Mileni M; Finn MG; Bornhop DJ Nat. Biotechnol 2011, 29 (4), 357–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lu H; Tonge PJ Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2010, 14 (4), 467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Copeland RA Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15 (2), 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Klein Herenbrink C; Sykes DA; Donthamsetti P; Canals M; Coudrat T; Shonberg J; Scammells PJ; Capuano B; Sexton PM; Charlton SJ; Javitch JA; Christopoulos A; Lane JR Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 10842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Schuetz DA; de Witte WEA; Wong YC; Knasmueller B; Richter L; Kokh DB; Sadiq SK; Bosma R; Nederpelt I; Heitman LH; Segala E; Amaral M; Guo D; Andres D; Georgi V; Stoddart LA; Hill S; Cooke RM; De Graaf C; Leurs R; Frech M; Wade RC; de Lange ECM; Ijzerman AP; Müller-Fahrnow A; Ecker GF Drug Discovery Today 2017, 22 (6), 896–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang W; Yang Y; Wang S; Nagaraj VJ; Liu Q; Wu J; Tao N Nat. Chem 2012, 4 (10), 846–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Höök F; Rodahl M; Kasemo B; Brzezinski P Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1998, 95 (21), 12271–12276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wu G; Datar RH; Hansen KM; Thundat T; Cote RJ; Majumdar A Nat. Biotechnol 2001, 19 (9), 856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Abdiche Y; Malashock D; Pinkerton A; Pons J Anal. Biochem 2008, 377 (2), 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fang Y; Ferrie AM; Fontaine NH; Yuen PK Anal. Chem 2005, 77 (17), 5720–5725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Liu S; Zhang H; Dai J; Hu S; Pino I; Eichinger DJ; Lyu H; Zhu H mAbs 2015, 7 (1), 110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Guan Y; Shan X; Zhang F; Wang S; Chen H-Y; Tao N Science Advances 2015, 1 (9), e1500633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ma G; Guan Y; Wang S; Xu H; Tao N Anal. Chem 2016, 88 (4), 2375–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hu S; Feng Y; Henson B; Wang B; Huang X; Li M; Desai P; Zhu H Anal. Chem 2013, 85 (17), 8046–8054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Shan X; Fang Y; Wang S; Guan Y; Chen H-Y; Tao N Nano Lett. 2014, 14 (7), 4151–4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fang Y; Chen S; Wang W; Shan X; Tao N Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54 (8), 2538–2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wang S; Shan X; Patel U; Huang X; Lu J; Li J; Tao N Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107 (37), 16028–16032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cai WZ; Person S; Warner SC; Zhou JH; DeLuca NA Journal of Virology 1987, 61 (3), 714–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wang W; Yin L; Gonzalez-Malerva L; Wang S; Yu X; Eaton S; Zhang S; Chen H-Y; LaBaer J; Tao N Sci. Rep 2015, 4, 6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Venkatakrishnan AJ; Deupi X; Lebon G; Tate CG; Schertler GF; Babu MM Nature 2013, 494 (7436), 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.