Abstract

Objective

This study examined the mediating role of internet addiction in the association between psychological resilience and depressive symptoms.

Methods

837 Korean university students completed a survey with items of demographic information, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), Internet Addiction Test (IAT), and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in 2015. The complex associations among psychological resilience, internet addiction, and depressive symptoms were delineated using structural equation models.

Results

In the most parsimonious model, the total effect and indirect effect of resilience on depressive symptoms via internet addiction, were statistically significant. The goodness of fit of the measurement model was satisfactory with fit indices, normed fit index (NFI) of 0.990, non-normed fit index (NNFI) of 0.997, comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.998, root mean square error (RMSEA) of 0.018 (90%CI=0.001–0.034); and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) of -21.049.

Conclusion

The association between psychological resilience and depressive symptoms was mediated by internet addiction in Korean university students. Enhancement of resilience programs could help prevent internet addiction and reduce the related depression risks.

Keywords: Mediation, Internet addiction, Resilience, Depression, University students

INTRODUCTION

Depressive symptoms are important to the diagnosis of sub-threshold types of depression in psychiatric practices [1]. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance of diagnostic and management of depression advises healthcare professionals to maintain a high awareness of depressive symptoms among young people [2]. Although depression is a major internalizing disorder in adolescents [3], not everyone could acquire the respective coping strategies [4]. Furthermore, tracking of depression from adolescence to adulthood is not uncommon [5].

Transition from adolescence to adulthood provides an opportunity for individuals to further develop their psychological resilience [6]. Psychological resilience is a concept derived from the vulnerability principle [7], with emerging neurological evidence of its self-regulatory function [8]. A 10-year cohort study has reported that CACNA1C SNP rs1006737 was a predisposition of resilience to depressive symptoms [9]. Magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) studies have shown high grey matter volumes at the right middle and superior frontal gyri [10] and high fractional anisotropy (FA) in the anterior corpus callosum (CC) among resilient adolescents when compared with others [11]. Hippocampal volume also served as a valid neural marker for assessing both psychological resilience and depression [12].

Epidemiological studies have also shown the relationships between health-related behaviors and psychological resilience to negative affects in adolescents [13]. School-based resilience trials for reducing substance use were found to be effective in adolescents [14,15]. In young adults, related resilience findings are mostly on substance uses, such as smoking [16] and drug use [17]. Individuals with addictive internet behaviors shared certain personality features with alcohol dependents [18], including impulsivity [19]. A systematic review has stipulated depression and anxiety as the psychological symptoms of addictive internet behaviors [20]. While there are findings showing the mediation model among resilience, internet addiction, and depression in children, no corresponding results in youth is available for clinical references [21].

This study examined the possible associations between resilience, depressive symptoms, and internet addiction with the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 1 (H1) is that resilience is negatively associated with the likelihood of internet addiction; Hypothesis 2 (H2) is that internet addiction is positively associated with depressive symptoms; Hypothesis 3 (H3) is that resilience is negatively associated with depressive symptoms.

Hypothesis 1

We hypothesize that better resilience will be associated with a lower likelihood of internet addiction. Previous studies have shown that psychological resilience was negatively associated with the risk of Internet addiction in children [21] and adolescents (β=-0.030) [22]. Similar associations were found in university students [23,24]. In Korean university students, the correlation coefficient between CD-RISC scores and IAT scores was -0.12 [25] and smartphone users (mean=59.06) had a significantly lower CD-RISC-determined resilience in at-risk than normal users (mean=66.54) [26].

Hypothesis 2

We hypothesize that internet addiction will be associated with depressive symptoms. Together with anxiety, depression is one of the major psychological factors of internet addiction in young people [27]. The associations between depressive symptoms and Internet addiction are well-established from studies with vary measurement scales [28-31]. Longitudinal study results also showed the causation between addicted online relationships and depressive symptoms in adolescents [32]. Depressive symptoms were also linked to poor psychosocial wellbeing via internet addiction in cross-population adolescent studies [33]. In adults, Internet addicted group was more likely to have depressive symptoms than others [34]. In university students, internet addiction was related to a higher risk of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)-determined depression in Turkey [27].

Hypothesis 3

We hypothesize that better psychological resilience will be associated with less symptoms of depressive symptoms. According to the depression model proposed by Beck and Bredemeier [35], positive predisposing, precipitating, and resilience factors all could reduce depressive symptoms. A youth cohort in Australia found that CD-RISC determined resilience led to Goldberg Depression and Anxiety Inventory-determined depressive symptoms [36]. In Korean adults with parental alcoholism, CD-RISC-determined resilience helped prevent the development of Beck Depression Inventory-determined depressive symptoms [37].

Based the three associations, several adolescent studies have further investigated the role of internet addiction in the associations between psychological resilience and negative affects. Resilience could mitigate the negative effects (measured by the Watson’s Positive and Negative Affect Scales) of internet addiction in US adolescents aged 13 to 17 [38]. A previous study among Chinese adolescents suggested that life events could mediate the association between internet addiction and depression [39]. Another Korean high school study suggested that psychological resilience could be associated with internet addiction via stress [40].

According to the 2016 Epidemiological Survey of Mental Disorders by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder in Korean adults was 5.0%. Among university students in Korea, keen academic competitions and career uncertainties are common and depression was a major risk factor of suicides [41]. However, the behavioral risk factors of suicidal ideation could be different between university men and women in Korea [42]. This study aimed to delineate the complex relationships of resilience, depressive symptoms, and internet addiction among Korean university students with a structural equation modeling approach.

METHODS

Administration

Students from a university in the Chungcheong Province of Korea were invited to complete a questionnaire in Korean language online in 2015. Informed consent was sought and their participations were voluntary and no incentive was provided. A total of 1184 students were invited, with 846 completed questionnaires received and 837 agreed to provide the information for research. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Kongju National University (KNU_IRB_2015-38).

Measures

In addition to demographic information, students responded to the following scale measures, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) (25 items), Internet Addiction Test (IAT) (20 items), and Patient Depression Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (9 items). The 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale is a common scale to assess psychological resilience [43], although its short-form 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale is available [44]. The five factors for CD-RISC are a) Personal Competence, b) Trust and Tolerance, c) Acceptance and Relationship Security, d) Control, and e) Spiritual influence. The responses are 5-point Likert scale (“Not true At all,” “Rarely true,” “Sometimes true,” “Often true,” “True nearly all of the time”). The possible total scores for CD-RISC are from 0 to 100, with higher score representing a better resilience level. Internet Addiction Test (IAT) has six responses (“Never or not applicable,” “Rarely,” “Occasionally,” “Sometimes,” “Often,” “Always”). The possible scores for IAT are 0 to 100, with higher score representing a higher risk of internet addiction. Besides, IAT has been translated and tested in college students across countries [45-47], including Korean college students [48] in which four factor structure was revealed. The PHQ-9 has four responses, including “not at all,” several days,” “more than half the days,” “nearly every day.” In addition, PHQ-9 has been tested among US [49] and Chinese college students [50]. An one-factor structure of PHQ-9 was found to be reliable (Cronbach’s alpha=0.837), test-retest reliable (r=0.650), and valid against Depression Inventory (BDI) and Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (r=0.509 to 0.807) among Korean medical students [51]. The possible scores range from 0 to 27, with a higher score indicating more depressive symptoms.

Data analysis

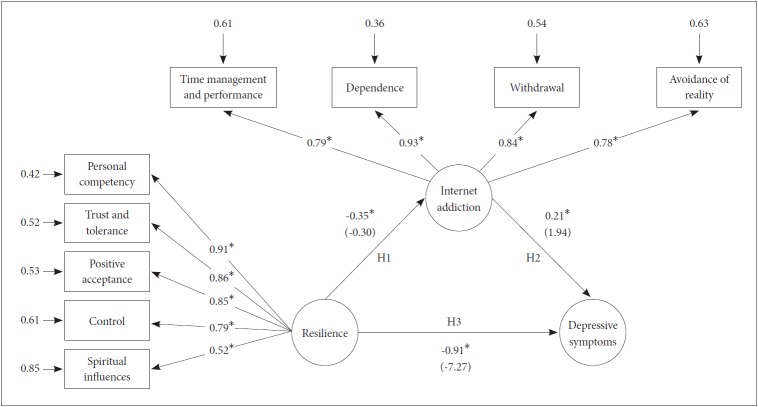

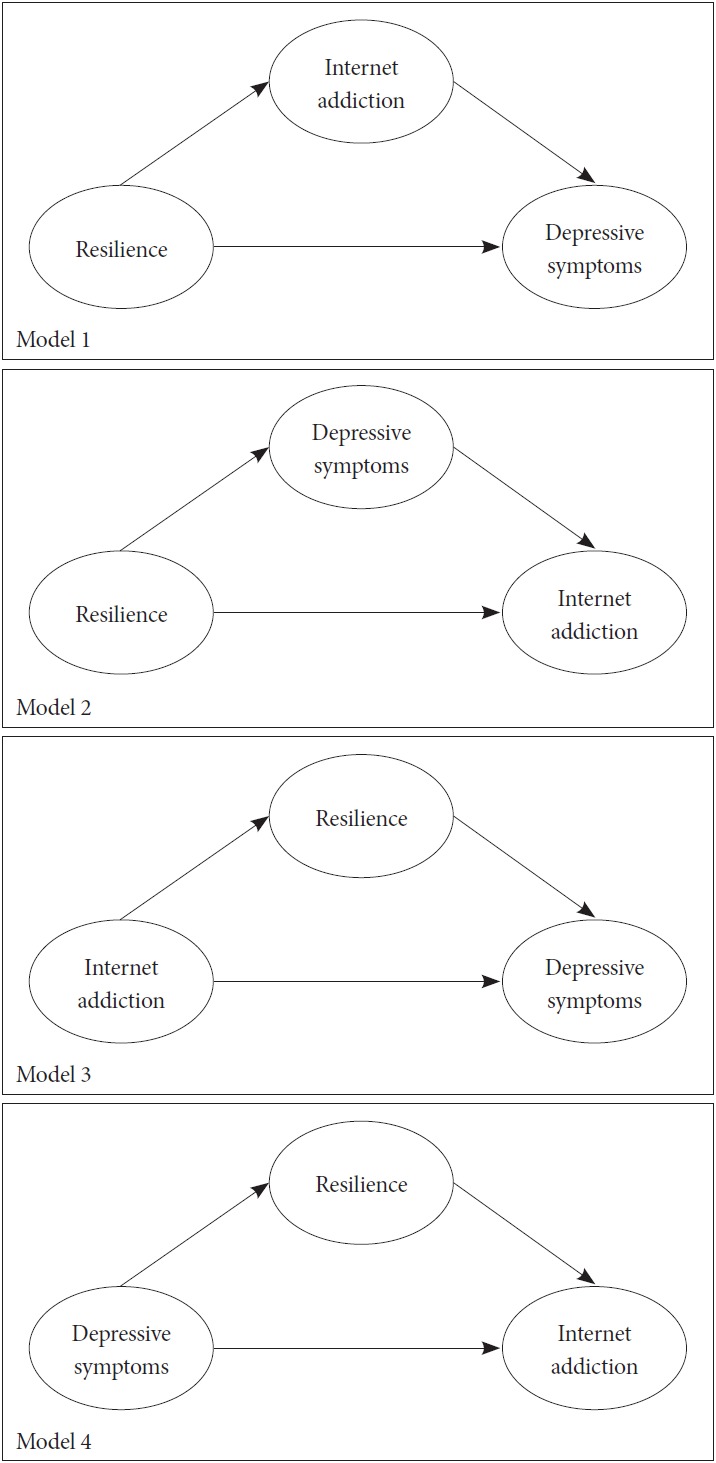

A total of 837 students were included in the main analysis. Gender differences of and correlations between the scales were tested using t-test and Pearson correlation coefficient, respectively. Possible conceptual models (Models 1 to 4) for modeling the relationships between resilience, depression, and internet addiction were constructed for comparisons (Figure 1). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to compute the model fit indices using the robust maximum likelihood method. Goodness-of-fit was regarded as acceptable if the values of normed fit index (NFI), and non-normed fit index (NNFI) [52]; and comparative fit index (CFI) [53]; were above 0.90; as well as root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [54] were below 0.08 [55]. The significance of the paths in the model was indicated by the Wald test. Models with smaller normal Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) values were preferred. All analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 for Windows (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) and EQS 6 (Multivariate Software, Encino, CA ,USA).

Figure 1.

Conceptual models for structural equation modeling.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

As shown in Table 1, university men had significantly higher CD-RISC total scores than women (63.88 SD=15.33 vs. 55.60 SD=15.70). However, university women had significantly higher PHQ-9 scores than men (6.25, SD=4.68 vs. 4.96, SD=5.07). There was no significant difference of IAT and its subscale scores between university men and women. Their respective IAT total scores were 22.14 (SD=15.22) and 22.41 (SD=16.97). The major scales, CD-RISC, PHQ-9, and IAT showed good internal consistency with corresponding Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.940, 0.865, and 0.946. In Table 2, CD-RISC-Total significantly (p<0.01) and negatively correlated with PHQ-9-Total (r=-0.500) and IAT-Total (r=-0.320). The correlation between PHQ-9-Total and IAT-Total was also significant (p<0.01) and positive (r=0.275). Significant correlations of same directions between these scale total values were found after stratification by sex. In addition, the subscales of CD-RISC, PHQ-9, and IAT also significantly correlated with each other.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics and measure scores

| Men (N=361) | Women (N=476) | t-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age | 22.7 (2.37) | 21.7 (1.82) | 7.246 | <0.001 |

| CD-RISC-total (Cronbach’s α=0.940) | 63.88 (15.33) | 55.6 (15.70) | 7.655 | <0.001 |

| CD-RISC personal competency and tenancy (8 items) | 20.57 (5.72) | 17.30 (5.79) | 8.133 | <0.001 |

| CD-RISC trust and tolerance (7 items) | 17.27 (4.60) | 14.44 (4.67) | 8.784 | <0.001 |

| CD-RISC acceptance of change and relationship security (5 items) | 13.98 (3.44) | 12.87 (3.47) | 4.590 | <0.001 |

| CD-RISC control (3 items) | 7.40 (2.49) | 6.71 (2.55) | 3.946 | <0.001 |

| CD-RISC spiritual influences (2 items) | 4.66 (1.54) | 4.29 (1.74) | 3.293 | 0.001 |

| PHQ (9-items) (Cronbach’s α=0.865) | 4.96 (5.07) | 6.25 (4.68) | -3.749 | <0.001 |

| IAT-total (20 items) (Cronbach’s α=0.946) | 22.14 (15.22) | 22.41 (16.97) | -0.239 | 0.81 |

| IAT-time management (9 items) | 13.35 (8.87) | 13.04 (9.49) | -0.925 | 0.355 |

| IAT-dependence (5 items) | 4.17 (3.71) | 4.27 (4.31) | -0.350 | 0.727 |

| IAT-withdrawal (3 items) | 1.91 (2.19) | 1.93 (2.52) | -0.105 | 0.916 |

| IAT-avoidance of reality (3 items) | 2.71 (2.39) | 2.27 (2.49) | 2.578 | 0.010 |

CD-RISC: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire, IAT: Internet Addiction Test, SD: standard deviation

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients among measure scores

| CD-RISC-total | PHQ-9-total | IAT-total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||

| CD-RISC-total | 1 | ||

| PHQ-9-total | -0.469* | 1 | |

| IAT-total | -0.400* | 0.332* | 1 |

| Women | |||

| CD-RISC-total | 1 | ||

| PHQ-9-total | -0.503* | 1 | |

| IAT-total | -0.282* | 0.237* | 1 |

| All | |||

| CD-RISC-total | 1 | -0.500* | -0.320* |

| CD-RISC-PCT | -0.436* | -0.327* | |

| CD-RISC-TT | -0.438* | -0.232* | |

| CD-RISC-ACRS | -0.481* | -0.296* | |

| CD-RISC-C | -0.456* | -0.328* | |

| CD-RISC-SI | -0.279* | -0.111* | |

| PHQ-9-total | 1 | ||

| IAT-total | -0.320* | 0.275* | 1 |

| IAT-TM | -0.302* | 0.253* | |

| IAT-D | -0.314* | 0.260* | |

| IAT-W | -0.246* | 0.188* | |

| IAT-AR | -0.223* | 0.254* |

p<0.01.

CD-RISC: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, CD-RISC-PCT: CD-RISC Personal Competency and Tenancy, CD-RISC-TT: CD-RISC Trust and Tolerance, CD-RISC-ACRS: CD-RISC-Acceptance of Change and Relationship Security, CD-RISC-C: CD-RISC Control, CD-RISC-SI: CD-RISC Spiritual Influences, IAT: Internet Addiction Test, IAT-TM: IAT-Time Management, IAT-D: IAT-Dependence, IAT-W: IAT-Withdrawal, IAT-AR: IAT-Avoidance of Reality, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire

Structural equation modeling

In Model 1, resilience had a significant and negative total effect on depressive symptoms (β=-0.981, SE=0.514, p<0.001). When internet addiction was considered as a mediator, resilience had a significant and negative indirect effect on depressive symptoms (β=-0.073, SE=0.183, p<0.001). The direct effects of resilience on depressive symptoms (β=-0.908) and internet addiction (β=-0.350) were significant and negative (Figure 2). In addition, the direct effect of depressive symptoms on internet addiction was significant and positive (β=0.208). The values of the fit indices for Model 1 were as follow: NFI of 0.990, NNFI of 0.997, CFI of 0.998, RMSEA of 0.018 (90%CI=0.001–0.034), and AIC of -21.049 (Table 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Measurement model (Model 1) for internet addiction, resilience, and depressive symptoms. Unstandardized parameter estimates are shown in parentheses under the standardized parameter estimates. *p<0.05. Resilience was measured by Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RTSC). Internet Addiction was measured by Internet Addiction Test (IAT). Depressive symptoms was measured by Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

Table 3.

Fit indices for the tested measurement models

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | NFI | NNFI | CFI | RMSEA (90%CI) | AIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 36.951 | 29 | 1.27 | 0.990 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.018 (0.001–0.034) | -21.049 |

| Model 2 | 93.412 | 29 | 3.22 | 0.974 | 0.972 | 0.982 | 0.052 (0.040–0.063) | 35.412 |

| Model 3 | 104.070 | 29 | 3.59 | 0.971 | 0.967 | 0.979 | 0.056 (0.044–0.067) | 46.070 |

| Model 4 | 113.791 | 29 | 3.92 | 0.968 | 0.968 | 0.976 | 0.058 (0.047–0.069) | 52.791 |

NFI: normed fit index, NFI: non-normed fit index, CFI: comparative fit index, RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation, CI: confidence interval, AIC: Akaike Information Criterion

Table 4.

Decompositions of effects in the tested structural equation models

| B (SE) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||

| Total effect | -0.981 (0.514) | <0.001 |

| Resilience → Depressive symptoms | ||

| Indirect effec | -0.073 (0.183) | <0.001 |

| Resilience → Internet addiction → Depressive symptoms | ||

| Model 2 | ||

| Total effect | -0.350 (0.065) | <0.001 |

| Resilience → Internet addiction | ||

| Indirect effect | -0.337 (0.110) | <0.001 |

| Resilience → Depressive symptoms → Internet addiction | ||

| Model 3 | ||

| Total effect | 0.506 (0.202) | <0.001 |

| Internet addiction → Depressive symptoms | ||

| Indirect effect | 0.306 (0.113) | <0.001 |

| Internet addiction → Resilience → Depressive symptoms | ||

| Model 4 | ||

| Total effect | 0.485 (0.120) | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms → Internet addiction | ||

| Indirect effect | -0.442 (0.150) | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms → Resilience → Internet addiction |

Resilience was measured by Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), Internet Addiction was measured by Internet Addiction Test (IAT), Depressive symptoms was measured by Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

In Model 2, resilience had a significant and negative total effect on Internet addiction (β=-0.350, SE=0.065, p<0.001). With depressive symptoms acting as a mediator, resilience had a significant and negative indirect effect on internet addiction (β=-0.337, SE=0.110, p<0.001). The fit indices for Model 2 were satisfactory with NFI of 0.974, NNFI of 0.972, CFI of 0.982, and RMSEA of 0.052 (90%CI=0.040–0.063), and AIC of 35.412 (Table 3 and 4). In Model 3, internet addiction had a significant and positive total effect on depressive symptoms (β=0.506, SE=0.202, p<0.001). Internet addiction had a significant and positive indirect effect on depressive symptoms, via resilience (β=0.306, SE=0.113, p<0.001). The fit indices for Model 3 were as follow: NFI of 0.971, NNFI of 0.967, CFI of 0.979, RMSEA of 0.056 (90%CI=0.0044–0.067), and AIC of 46.070 (Table 3 and 4). In model 4, internet addiction had a significant and positive total effect on depressive symptoms (β=0.485, SE=0.120, p<0.001); and a significant and negative indirect effect on internet addiction through resilience (β=-0.442, SE=0.150, p<0.001). The fit indices for Model 4 were as follow: NFI of 0.968, NNFI of 0.968, CFI of 0.976, RMSEA of 0.058 (90%CI=0.047–0.069), and AIC 52.791 (Table 3 and 4). Among Models 1 to 4, Model 1 was regarded as the most parsimonious model with satisfactory model fit (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study reported the mediating role of internet addiction between psychological resilience and depressive symptoms among Korean university students, using a structural equation modeling approach. In our descriptive results, the higher level of resilience in university men than women is consistent to the previous findings from a twin study [56]. Moreover, university women were found to have more depressive symptoms than men in this study. Such a sex difference was also reported previously in university students from Korea and US [57], as well as Europe [58]. The average age of university men was higher than that of women in this sample, owing to the mandatory military services for Korean men. This may also contribute to the observed sex differences of the scores of major measures.

From the structural equation models, students with a lower level of resilience are generally more vulnerable to addictive internet behaviors which is consistent to the previous findings [59]. Indeed, a poor defense or maladaptation system could be associated with Internet addiction [60]. A meta-analysis of internet addiction studies in Korea also revealed that poor coping of stress is a risk factor of internet addiction [61]. In reverse, better coping styles [62] and adaptations [60] are protective against the risks of addictive internet behaviors. The association between internet addiction and more depressive symptoms could be viewed as one of the psychiatric comobidities of internet addiction, as shown in a meta-analysis [63]. At the same time, the association of higher resilience with less depressive symptoms observed is probably due to more effective coping strategies against adverse conditions for the resilient group than others [64,65]. A further examination of the domains of the scales being used to assess psychological resilience and internet addiction could help explain the association between psychological resilience and risks of internet addiction. One of the characteristics of addictive internet behaviors is poor time management. Resilient students with better personal competency (awareness and self-management) and stress tolerance could avoid entering into an adaptive state of developing internet dependence and later withdrawal. Finally, resilient students could better trust in own instinct, to maintain healthy spirituality and control themselves from avoiding reality. When applying these results to real life, students with stronger resilience would be less susceptible to the comobidity of internet addiction than their peers, and have a better transition from adolescents to young adults.

There are some limitations to the interpretation of results and applications to health promotion and clinical practices. With a cross-sectional study design, the casual relationships between the major variables could not be established. The major variables used to construct the measurement models were based on self-reported information. Social desirability and recall biases recall biases could affect the internal validity. According to Soule et al. [66], there are six major forms of internet addiction, including communication addiction and game addiction. The mediation effect of internet addiction on the association between psychological resilience and depressive symptoms found in this study may not be generalized to all forms of internet addiction. Unlike PHQ-15, PHQ-9 does not screen for somatic symptoms, which could be related to depression [67]. However, three typical depressive symptoms, namely depressed mood, anhedonia, and reduced energy from DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 are covered by PHQ-9. PHQ-9 has also been used to screen depressive symptoms related to maladaptive use of information technology, such as Facebook [68]. Personality which is one of the key determinants of internet behaviors [69]; as well as other potential mediators including social support [70], coping styles [71], and coping flexibility [72] were not investigated in this study. In addition, sleep quality which could mediate internet addiction and depression in university students [73] was not included.

According to the Korean Education Statistics Service, there are 183483 male (51.6%) and 172289 (48.4%) female students enrolled in universities in Korea. When comparing this ratio with that of our sample, only a small Cohen effect size of 0.12 was found. This suggests a representative sample being used in this study. To ensure the parsimoniousness of the resulting model, possible mediation models with depression [74] and resilience as mediators [38] were enumerated and tested before the final model was confirmed. Furthermore, all candidate models were tested with stratification by sex, as a sensitivity test. Although available literature stated that using gaming as maladaptive coping strategies are relatively more common in men than women [75], our final model was applicable to both university men and women.

The current results have important implications for future development of guidelines of resilience-based interventions of negative affects [76]. Exercise-based intervention was found to be effective in reducing psychological symptoms relating to internet addiction, including depression (standardized mean difference=-0.85, 95%CI=-1.20 to -0.49) in a meta-analysis among East Asian studies. Exercise-based resilience strengthening programs could potentially be incorporated into clinical practices for reducing depressive symptoms [77].

In conclusion, internet addiction mediates the associations between resilience and depressive symptoms in Korean university students. Enhancing resilience is important to prevent addictive internet behaviors and the related depressive symptoms among young people.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayuso-Mateos JL, Nuevo R, Verdes E, Naidoo N, Chatterji S. From depressive symptoms to depressive disorders: the relevance of thresholds. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:365–371. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.071191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins K, Crosland P, Elliott N, Bewley S, Clinical Guidelines Update Committee B Diagnosis and management of depression in children and young people: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h824. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379:1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2014;5 doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinherz HZ, Paradis AD, Giaconia RM, Stashwick CK, Fitzmaurice G. Childhood and adolescent predictors of major depression in the transition to adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2141–2147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masten AS, Burt KB, Roisman GI, ObradoviĆ J, Long JD, Tellegen A. Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: continuity and change. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:1071–1094. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elisei S, Sciarma T, Verdolini N, Anastasi S. Resilience and depressive disorders. Psychiatr Danub. 2013;25(Suppl 2):S263–S267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo SJ, Murrough JW, Han MH, Charney DS, Nestler EJ. Neurobiology of Resilience. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1475–1484. doi: 10.1038/nn.3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strohmaier J, Amelang M, Hothorn LA, Witt SH, Nieratschker V, Gerhard D, et al. The psychiatric vulnerability gene CACNA1C and its sex-specific relationship with personality traits, resilience factors and depressive symptoms in the general population. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:607–613. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burt KB, Whelan R, Conrod PJ, Banaschewski T, Barker GJ, Bokde ALW, et al. Structural brain correlates of adolescent resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57:1287–1296. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galinowski A, Miranda R, Lemaitre H, Paillère Martinot ML, Artiges E, Vulser H, et al. Resilience and corpus callosum microstructure in adolescence. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2285–2294. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan SW, Harmer CJ, Norbury R, O’Sullivan U, Goodwin GM, Portella MJ. Hippocampal volume in vulnerability and resilience to depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;189:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rew L, Horner SD. Youth resilience framework for reducing health-risk behaviors in adolescents. Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18:379–388. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodder RK, Freund M, Bowman J, Wolfenden L, Campbell E, Wye P, et al. A cluster randomised trial of a school-based resilience intervention to decrease tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use in secondary school students: study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1009. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodder RK, Daly J, Freund M, Bowman J, Hazell T, Wiggers J. A school-based resilience intervention to decrease tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use in high school students. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:722. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colgan Y, Turnbull DA, Mikocka-Walus AA, Delfabbro P. Determinants of resilience to cigarette smoking among young Australians at risk: an exploratory study. Tob Induc Dis. 2010;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis SJ, Spillman S. Reasons for drug abstention: a study of drug use and resilience. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43:14–19. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.566492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Z, Zhu H, Li C, Wang J. Internet addictive individuals share impulsivity and executive dysfunction with alcohol-dependent patients. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:288. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell MR, Potenza MN. Addictions and personality traits: impulsivity and related constructs. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40473-013-0001-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carli V, Durkee T, Wasserman D, Hadlaczky G, Despalins R, Kramarz E, et al. The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: a systematic review. Psychopathology. 2013;46:1–13. doi: 10.1159/000337971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou P, Zhang C, Liu J, Wang Z. The relationship between resilience and internet addiction: a multiple mediation model through peer relationship and depression. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2017;20:634–639. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Shi M, Wang Z, Shi K, Yang C. Resilience as a predictor of internet addiction: The mediation effects of perceived class climate and alienation. 2010 IEEE 2nd Symposium on Web Society; 2010 Aug 16-17; Beijing, China. 2010. pp. 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terwase JM, Ibaishwa RL. Resilience, shyness and loneliness as predictors of internet addiction among university undergraduate students in benue state country. J Hum Soc Sci. 2014;19:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakraborti A, Ray P, Islam M, Mallick A. Medical undergraduates and pathological internet use: Interplay of stressful life events and resilience. J Health Spec. 2016;4:56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi SW, Kim DJ, Choi JS, Ahn H, Choi EJ, Song WY, et al. Comparison of risk and protective factors associated with smartphone addiction and Internet addiction. J Behav Addict. 2015;4:308–314. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SM, Huh HJ, Cho H, Kwon M, Choi JH, Ahn HJ, et al. The effect of depression, impulsivity, and resilience on smartphone addiction in university students. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2014;53:214–220. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalbudak E, Evren C, Aldemir S, Evren B. The severity of Internet addiction risk and its relationship with the severity of borderline personality features, childhood traumas, dissociative experiences, depression and anxiety symptoms among Turkish university students. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yen JY, Yen CF, Wu HY, Huang CJ, Ko CH. Hostility in the real world and online: the effect of internet addiction, depression, and online activity. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:649–655. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alpaslan AH, Soylu N, Kocak U, Guzel HI. Problematic internet use was more common in Turkish adolescents with major depressive disorders than controls. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105:695–700. doi: 10.1111/apa.13355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirao K. Difference in mental state between Internet-addicted and non-addicted Japanese undergraduates. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;27:307–310. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2014-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni X, Yan H, Chen S, Liu Z. Factors influencing internet addiction in a sample of freshmen university students in China. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12:327–330. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gamez-Guadix M. Depressive symptoms and problematic internet use among adolescents: analysis of the longitudinal relationships from the cognitive-behavioral model. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:714–719. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai CM, Mak KK, Watanabe H, Jeong J, Kim D, Bahar N, et al. The mediating role of Internet addiction in depression, social anxiety, and psychosocial well-being among adolescents in six Asian countries: a structural equation modelling approach. Public Health. 2015;129:1224–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geisel O, Panneck P, Stickel A, Schneider M, Muller CA. Characteristics of social network gamers: results of an online survey. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:69. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AT, Bredemeier K. A Unified model of depression: integrating clinical, cognitive, biological, and evolutionary perspectives. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4:596–619. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roy A, Sarchiapone M, Carli V. Low resilience in suicide attempters: relationship to depressive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:273–274. doi: 10.1002/da.20265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee H, Williams RA. Effects of parental alcoholism, sense of belonging, and resilience on depressive symptoms: a path model. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48:265–273. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.754899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wisniewski P, Jia H, Wang N, Zheng S, Xu H, Rosson MB, et al. Resilience mitigates the negative effects of adolescent internet addiction and online risk exposure. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2015 April 18-23; Seoul, Republic of Korea. New York: ACM; 2015. pp. 4029–4038. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L, Sun L, Zhang Z, Sun Y, Wu H, Ye D. Internet addiction, adolescent depression, and the mediating role of life events: finding from a sample of Chinese adolescents. Int J Psychol. 2014;49:342–347. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang JN, Choi YH. Pathways from family strengths and resilience to internet addiction in male high school students: mediating effect of stress. J Korean Public Health Nurs. 2012;26:375–388. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee K, Lee HK, Kim SH. Temperament and character profile of college students who have suicidal ideas or have attempted suicide. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi SB, Lee W, Yoon JH, Won JU, Kim DW. Risk factors of suicide attempt among people with suicidal ideation in South Korea: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:579. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4491-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez-Villa T, Molina AJ, Garcia-Martin M, Llorca J, Delgado-Rodriguez M, Martin V. Validation and psychometric analysis of the Internet Addiction Test in Spanish among college students. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:953. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2281-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jelenchick LA, Becker T, Moreno MA. Assessing the psychometric properties of the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) in US college students. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ko CH, Hsiao S, Liu GC, Yen JY, Yang MJ, Yen CF. The characteristics of decision making, potential to take risks, and personality of college students with Internet addiction. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee K, Lee HK, Gyeong H, Yu B, Song YM, Kim D. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the internet addiction test among college students. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:763–768. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.5.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams A, Larocca R, Chang T, Trinh NH, Fava M, Kvedar J, et al. Web-based depression screening and psychiatric consultation for college students: a feasibility and acceptability study. Int J Telemed Appl. 2014;2014:580786. doi: 10.1155/2014/580786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang YL, Liang W, Chen ZM, Zhang HM, Zhang JH, Weng XQ, et al. Validity and reliability of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 to screen for depression among college students in China. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5:268–275. doi: 10.1111/appy.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoon S, Lee Y, Han C, Pae CU, Yoon HK, Patkar AA, et al. Usefulness of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for Korean medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38:661–667. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance-structures. Psychol Bull. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behav Res. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bentler PM. On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the bulletin. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:400–404. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amstadter AB, Myers JM, Kendler KS. Psychiatric resilience: longitudinal twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:275–280. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.130906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwon H, Yoon KL, Joormann J, Kwon JH. Cultural and gender differences in emotion regulation: relation to depression. Cogn Emot. 2013;27:769–782. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.792244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ristic-Ignjatovic D, Hinic D, Jakovljevic M, Fountoulakis K, Siepera M, Rancic N. A ten-year study of depressive symptoms in Serbian medical students. Acta Clin Croat. 2013;52:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al-Gamal E, Alzayyat A, Ahmad MM. Prevalence of internet addiction and its association with psychological distress and coping strategies among university students in Jordan. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2016;52:49–61. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yao B, Han W, Zeng L, Guo X. Freshman year mental health symptoms and level of adaptation as predictors of Internet addiction: a retrospective nested case-control study of male Chinese college students. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koo HJ, Kwon JH. Risk and protective factors of internet addiction: a meta-analysis of empirical studies in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55:1691–1711. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.6.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang J, Yu Y, Du Y, Ma Y, Zhang D, Wang J. Prevalence of internet addiction and its association with stressful life events and psychological symptoms among adolescent internet users. Addict Behav. 2014;39:744–747. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ho RC, Zhang MW, Tsang TY, Toh AH, Pan F, Lu Y, et al. The association between internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:183. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steinhardt M, Dolbier C. Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56:445–453. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.44.445-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nazir A, Mohsin H. Coping styles, aggression and interpersonal conflicts among depressed and non-depressed people. Health Promot Perspect. 2013;3:80–89. doi: 10.5681/hpp.2013.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soule LC, Shell LW, Kleen BA. Exploring internet addiction: demographic characteristics and stereotypes of heavy internet users. J Comput Inform Syst. 2003;44:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Han H, Wang SM, Han C, Lee SJ, Pae CU. The relationship between somatic symptoms and depression. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2014;35:463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tran TB, Uebelacker L, Wenze SJ, Collins C, Broughton MK. Adaptive and maladaptive means of using facebook: a qualitative pilot study to inform suggestions for development of a future intervention for depression. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21:458–473. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cho SC, Kim JW, Kim BN, Lee JH, Kim EH. Biogenetic temperament and character profiles and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in Korean adolescents with problematic Internet use. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11:735–757. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reinelt E, Barnow S, Stopsack M, Aldinger M, Schmidt CO, John U, et al. Social support and the serotonin transporter genotype (5-HTTLPR) moderate levels of resilience, sense of coherence, and depression. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2015;168B:383–391. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mahmoud JS, Staten R, Hall LA, Lennie TA. The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33:149–156. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.632708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kato T. Development of the coping flexibility scale: evidence for the coping flexibility hypothesis. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59:262–273. doi: 10.1037/a0027770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhandari PM, Neupane D, Rijal S, Thapa K, Mishra SR, Poudyal AK. Sleep quality, internet addiction and depressive symptoms among undergraduate students in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:106. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1275-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cho S, Kwon JH. The effect of emotion regulation on internet game overuse: a mixture of buffering effect and promoting effect. Kor J Clin Psychol. 2015;34:411–428. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen KH, Oliffe JL, Kelly MT. Internet gaming disorder: an emergent health issue for men. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12:1151–1159. doi: 10.1177/1557988318766950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Luthar SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:857–885. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yoshikawa E, Nishi D, Matsuoka YJ. Association between regular physical exercise and depressive symptoms mediated through social support and resilience in Japanese company workers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:553. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3251-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]