Abstract

India has done well in eye care delivery by recognizing visual impairment and blindness as a major medical challenge. Major contributions have come from ophthalmologists (mass cataract surgery in the early 1900s; major participation of non-government organizations), policy makers (National Program for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment 1976; systematic development under the World Bank assisted India Cataract Project, 1995–2002), and the industry (manufacturing of affordable surgical instruments and medicines). Although the country could boast of higher cataract surgical coverage and near-total elimination of trachoma, there is increasing prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and undetected glaucoma. India is in the crossroad of adherence to old successful models of service delivery and adoption of new innovative methods of teaching and training, manpower development and skill-based training, relevant medical research and product development. In the absence of these new approaches, the initial gains in eye care could not be furthered in India. A new approach, that will combine the best of the “old” tradition of empathy and the “new” technology of analytics, is required to imagine the future of eye care in India.

Keywords: Eye care, India, planning

Professor Lalit Prakash Agarwal was a visionary who shaped the field of eye care in India with vision and wisdom. Many eye care organizations in India have been built on the attributes of his imagination. Fifty-one years ago, in 1967, he built the premier eye institute named after the first President of India, the Dr. Rajendra Prasad Center for Ophthalmic Sciences (as part of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India), which has been designed to maintain high standards of patient care, residency training, and clinical research. In the mid-1970s, he helped write the policy of visual impairment and blindness in India, in deed the first time in the world.[1] His advocacy, guidance, and vision made India the first country in the world to start a National Program for Prevention of Visual Impairment and Control of Blindness (now called National Program for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment, NPCB) in 1976. It was again his insight to create a federation of eye care institutions to promote vision science (the Federation of Ophthalmic and Optometry Research Education Center) and introduce the Diploma in Ophthalmic Technique course.[2]

These five decades have witnessed many changes. We wish to discuss the nature and the quantum of these significant transitions that have arisen during the past 5 decades due to the shift in the pattern and causes of disease and death.

Health Transition

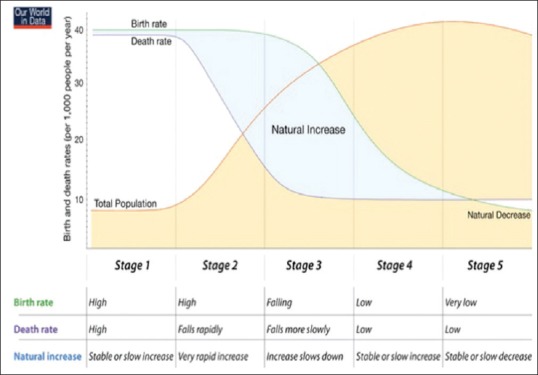

The two components of health transition are (1) demographic transition and (2) epidemiologic transition. The demographic transition describes the changes from the high fertility and high mortality rates seen in less developed societies to the low fertility and low mortality rates, typical of developed societies. The epidemiologic transition describes the changes in mortality and morbidity patterns (from infectious to chronic diseases) as the demographic, economic, and social structures of a society change.[3] There are four phases of epidemiologic transition (originally Orman described 3 phases; Olshansky and Ault[4] added the fourth phase). Table 1 and Fig. 1 show the main characteristics of the epidemiologic transition (https://www.ourworldindata.org).

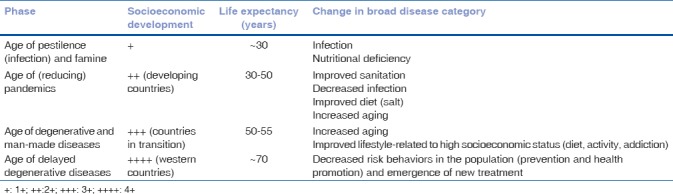

Table 1.

Four stages of health transition

Figure 1.

Epidemiological transition (source: https://www. ourworldindata.org)

Age of pestilence and famine refers to the preindustrial period, the prehistory to about the 1750s when both fertility and mortality rates were high, but the population was low because of famine, malnutrition, and epidemics. Age of receding pandemics dates from the 1750s to the early 1920s; this period witnessed rapid population growth, with high rates of fertility and decreases in rates of mortality. Age of degenerative and man-made disease was the modern urban industrial era when the fertility rates became controlled; the mortality rates remained low but life expectancy rates rose higher. This was the period of dramatic rise in heart disease, cancer, and stroke. The health system that oriented from curative to preventive care became more important. But the medical costs also swelled; rich bought better care and the poor could not afford. Age of delayed degenerative diseases consisted of continuously slow and fluctuating mortality rates, attributed to advances in medical technology, health care programs for the aged, and reductions in risk factors in communities.

The health transition is a dynamic process – a process where the health and disease patterns of a society evolve in response to the broader demographic, socioeconomic, technological, political, cultural, and biological changes.[5] Three major mechanisms are involved – the decline in fertility, the changes in risk factors, and the improvement in healthcare technology.[6] A decline in fertility results in the change in the distribution of people from younger age to adults. The changes in risk factors act primarily on the incidences of diseases. Improvement in healthcare technology impacts the case fatality rates from both infectious and noncommunicable causes. These three mechanisms may appear in different periods in different societies and may not actually obey a particular time frame. There could be overlaps of different periods and sometime a reversal trend also occurs. The latter trend includes the emergence of AIDS and more recently Ebola virus, and the re-emergence of tuberculosis.

What Is the Indian Position in Health Transition?

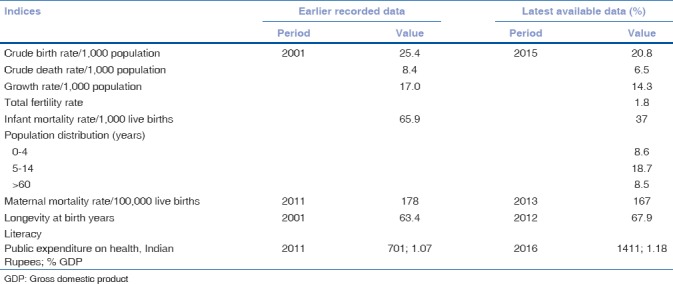

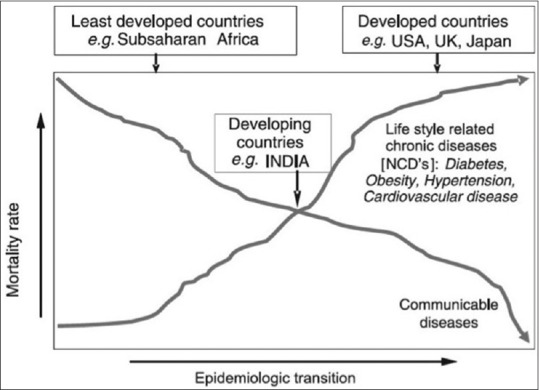

India is in the middle of an evolution, between the less developed and more developed countries, as Table 2 and Fig. 2 show. The country is engaged in a dual fight of “containing” a developing country's disease pattern and “delaying” a developed country's health disorders.[7]

Table 2.

Salient health-related indices in India[8]

Figure 2.

India and health transition process (source: Anjana RM et al.[7])

Although communicable diseases have declined, the lifestyle-related chronic diseases have increased. Table 2 shows the important health indices of India.[8]

India has to fight a double battle against both communicable and noncommunicable diseases. Undoubtedly, the country appears to have done well in healthcare delivery, including eye care. India was the first country (1976) to recognize blindness and visual impairment as an important health priority.[9] But for a longtime this program had been cataract centric with little focus on a universal eye care system.[10] The cataract surgical rate (CSR; 5,136/million population in 2016)[9] and the cataract surgical coverage have increased in India, but it is not uniformly spread across the country. As per the 2016 reports, the CSR was above the national average in 9 states, close to the national average in 2 states, and below the national average in 20 of the 31 Indian states and Union Territories.[9]

In order to providing equitable and accessible eye care, the World Health Organization (WHO) urged all member states to adopt universal eye health coverage and to this effect the World Health Assembly passed the resolution of global action plan (GAP) in 2013 (WHA 66.4).[11] The GAP suggested that the governments: (1) make adequate provisions covering curative, promotive, preventive, and rehabilitative measures for major causes of visual impairment, (2) provide access to everyone irrespective of economic status, ethnicity, gender, place of habitat, and disability status, (3) work toward integration of eye health with national health system, and finally (4) ensure equity of service such as not prevent access for the poorest. It was envisioned that these measures would reduce the global eye disease burden by 25% in five years, 2014–2019, using 2010 data as the baseline.

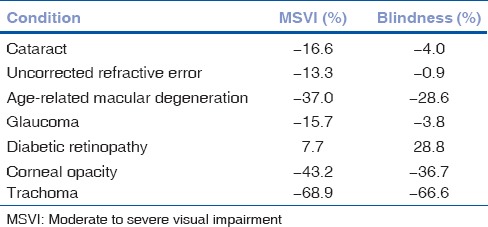

Global Burden of Eye Disease

Recently, the Vision Loss Expert Group has reported the magnitude of blindness and visual impairment as of the year 2015.[12] It stated that of 2015 world population of 7.33 billion people, 253 million people were blind or visually impaired (36 million blind and 216.8 million with moderate to severe visual impairment, MSVI). Females were more affected than men – 56% blind and 55% MSVI. The largest number of blind and visually impaired people lived in Asia. This report further stated that the global blindness has decreased from 0.75% in 1990 to 0.48% in 2015 and the global MSVI has decreased from 3.83% to 2.90% between these years. However, the absolute number of blind people has increased from 30.6 million in 1990 to 36.0 million in 2015 (17.9% increase) and the people with MSVI has increased from 159.9 million in 1990 to 216.6 million in 2015 (35.5% increase). The crude prevalence of all eye diseases except diabetic retinopathy has decreased [Table 3].[13] The crude prevalence of disease in 2015 compared to that in 1990 is calculated as follows:

Table 3.

Trend of prevalence of common eye disease in 2015 compared to 1990[13]

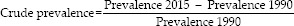

Although the decline in percentage of global blindness and MSVI could be attributed to the socioeconomic development, targeted public health programs, and improved access to eye health services, the increase in the absolute number of blind and visually impaired people is due to increased population and population ageing.[14] It is also predicted that the global MSVI and blindness would further increase by the year 2020 – MSVI to 237.1 million (from 216.1 million in 2015; 9.5% increase) and blindness to 38.5 million (from 36.0 million in 2015; 7.0% increase) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Predicted visual impairment of common eye disorders in 2020 compared to 2015[13]

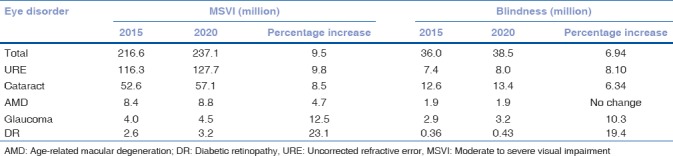

The Solution

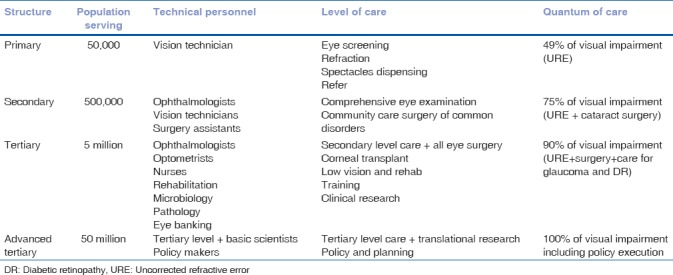

In order to improve the quantum of service delivery, we need a structural model, which should be able to deliver appropriate comprehensive eye care that is easily accessible and affordable. Such a model has recently been proposed and executed.[15] This pyramidal model of eye care is illustrated in Fig. 3 and Table 5.[16]

Figure 3.

Eye health pyramid

Table 5.

Structure and function of eye health pyramid[16]

The “Classical” Eye Camp Model: Merits and Demerits

India has pioneered “mass” cataract surgery. In this system, a large number of patients are gathered and examined in a make-shift eye examination area, and the operable cataracts are identified and operated in make-shift operating rooms. This approach certainly helped in reaching out to many patients, but the outcome was suboptimal, mostly related to inadequate postoperative care.[17,18] Additionally, in nearly three quarters of them the reach did not extend beyond a distance of 5 km.[19] Over a period of time a mixed model emerged in India where the patients’ screening continued as before, but the eligible cataract patients were transported to the hospital for surgery. This provided a good operating room and some postoperative care, but the quality of surgery was still compromised because a large number of patients were operated in a limited period of time. Additionally, this process of ferrying patients did not improve the follow-up care and the health seeking behavior of the people.

These issues were to a large extent sorted out when the eye care facility moved close to the community and delivered comprehensive eye care round the year. A study in South India reported that with a fixed comprehensive eye care facility in a rural Indian state, the blindness decreased from 11% to 8% and good outcome after cataract surgery (WHO definition of >6/18 in operated eye) increased from 32% to 66% in a decade of service.[20]

Imagining Eye Care in India

Where should India focus on eye care? Imagining eye care in India today must begin with a resolve to provide comprehensive and appropriate eye care as close as possible to where people live. It needs to build the pyramidal (or similar) eye care system, train required number of eye health personnel, equip and maintain the infrastructure for safe and quality eye care delivery, emphasize on comprehensive ophthalmologists as much as the super specialists, and finally bring a synergy between the public and private eye care providers. The Indian health delivery system has the basic foundation of health delivery system from village to city, a number of organizations train healthcare personnel, and the government provides some incentives for delivery of eye care. The greatest crunch lies in the urban centric preference of trained healthcare personnel, similar to the other parts of the world and the Southeast Asian countries.[21] This must be addressed urgently in order to achieve universal eye care in India.

Eye health personnel and training

There are 462 medical schools in India.[8] Currently, 241 (118 public, 123 private) institutions train residents for the Masters (MS/MD) program, 120 (66 public, 54 private) institutions train residents for Diploma (DO/DOMS) program, and 66 institutions train residents for the National Board of Examination program. Every year over 1,500 (1,026 MS/MD, 355 DO/DOMS, and 147 DNB) ophthalmologists are trained.[22] Although we could boast about this number, we cannot boast of the uniform quality of training. A recent survey of over 500 ophthalmologists interviewed 2–10 years after their residency commented that their residency training in basic diagnostic skills was just average, the refraction skill was dismally poor, training in modern cataract surgery (phacoemulsification) was suboptimal, and close to 50% of the respondents did not perform surgery under supervision.[23] The report further added that, in a scale of 0–10, the resident's exposure to eye bank was only 5.0 (±3.5) and to community ophthalmology was 6.1 (±3.1)

The importance and necessity of allied ophthalmic personnel (AOP) in delivery of eye care is being increasingly recognized.[24] There are 2 optometry programs in India – a 4-year Bachelor in Optometry program and 2-year Ophthalmic Assistant program. Approximately 3,000 optometrists are trained every year, but many of them do not practice clinical optometry for one reason or other, and most of them do not volunteer to work in rural areas. It is a worldwide phenomenon that a higher qualified person prefers to stay in urban areas. Hence, in order to bridge this gap the International Joint Commission on Allied Health Personnel in Ophthalmology offers a variety of certificate courses in ophthalmology.[25] Some medical universities in India offer some of these courses to high school graduates using different names.[26] At the conclusion of this 2-year program consisting of training and internship, the trained AOPs could independently perform an external eye examination, measure vision and intraocular pressure, perform refraction, dispense spectacles, diagnose common eye diseases for adequate referral, assist ophthalmic surgery, and participate in the delivery of postoperative care. Unfortunately, many state governments do not recognize these certificate courses. Now that the Health Sector Skill Council of the National Skill Development Council, a Government of India initiative, also offers 1-year (Certificate in Ophthalmic Assistant) and 2-year (Diploma in Ophthalmic Assistant) program,[27] one can hope that these trained AOPs will be recognized by the state government health system for appropriate placement.

Ophthalmic surgical assisting needs very special skills. This is offered as specialized 1- or 2-year programs after basic nursing training in many developed nations.[28,29,30] There are very few such dedicated ophthalmic nursing courses in India.[26] It will be beneficial to have specialized courses for ophthalmic nursing in India – 2-year certificate program for fresh high school graduates (Certified Ophthalmic Surgical Assistant, OSA) or 1-year program for Certified Auxiliary Nurse Midwife.

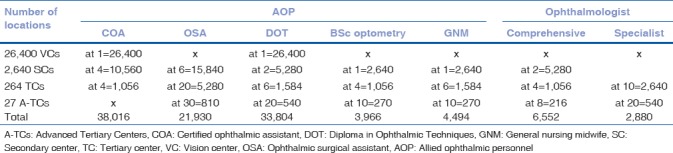

Based on the current Indian population of a little over 1.32 billion (2016 population), we estimate that good universal eye health coverage would need at the minimum 26,400 vision centers, 2,640 secondary centers, 264 tertiary centers, and 27 centers of advanced tertiary care. These centers would need 98,244 allied eye health personnel and 6,832 practicing ophthalmologists [Table 6]. This crude estimate does not include optical dispensing persons, and the need for a larger number of skilled people in busy and large hospitals.

Table 6.

Estimate of services and eye health personnel in India

Research, publication, and public health

The research and publications from Indian medical institutions do not match the service they provide in all specialties of medicine including ophthalmology. A 2004–2014 survey of peer-reviewed English language publications from India showed that only 25 medical schools in India had 100+ annual publications and 57.3% of medical schools did not have a single publication. The field of ophthalmology was leading in single specialty institutions and the first 10 included 2 specialty eye hospitals (both of them in South India).[31] There is an increasing need for the country to encourage at least 10% of the medical graduates to pursue the MD/PhD program and 5% of medical graduates to pursue the public health (MD/MPH) programs. The MD/PhD program will create clinical scientists to translate research from bench to bedside, collaborate with basic scientists, and the industry to create new treatment paradigms. Right incentives of funding and early career support are required for these programs to succeed.[32,33] In Singapore, the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) has succeeded bringing together the academia and hospitals, and built a synergy between the public and private sector to drive research-development and innovation for economic and social outcomes.[34] A*STAR has been successfully derived considerable funding from industry around the world for a new order of scientific research in Singapore.

India has also initiated the process by establishing two research promotion organizations – the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB)[35] a decade ago and the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC)[36] under the Department of Biotechnology 3 years ago. The SERB provides assistance for research in science and engineering; the BIRAC finances development of nationally relevant products. We have to wait to see the impact of SERB and BIRAC in the area of new medical discoveries. The MD/MPH program on the other hand provides a core foundation in medicine and public health to equip the candidates with required clinical skills and science to addressing health and wellness from both perspective of the individual patient, the community, and the general population. Their great value lies in public health research and in policy planning.

Big data analysis

Big data means a large chunk of raw data that are collected, stored, and analyzed to help increase efficiency and decision-making. Three important arms of big data are the volume, the velocity, and the variety. The starting point of big data acquisition and analysis is the electronic health record (EHR) that ensures uniform and detailed documentation. The American Academy of Ophthalmology has been collecting these big data in ophthalmology since 2014. Named IRIS – Intelligent Research In Sight – it is USA's first EHR-based comprehensive eye disease registry.[37] IRIS is a centralized data repository and reporting tool that analyzes patient data to produce easy-to-interpret national and interpractice benchmark reports and provides scientific information to improve public health. As of July 1, 2017, the registry has collected data of 37.3 million unique patients and 148 million patient visits collected from 13,199 practicing ophthalmologists and has analyzed all common eye diseases.[38] The additional benefits of EHR lie in facilitation for teleconsultation and supply chain management to improve patient safety and accountability.

The Government of India has demonstrated an intention toward standardized collection, storage, and exchange of big health data by setting up a National eHealth Authority (NeHA) in 2015. The vision of NeHA is “attainment of high quality health services for all Indians through cost-effective and secure use of information and communication technologies in health and health-related fields.”[39] But the progress has been very tardy, and essentially nonexistent in ophthalmology. With active support from both public and private (includes NGOs), a total of 6.481 million cataract surgeries were performed in India in the years 2016–2017.[9] This is nearly a quarter of all cataract surgeries done in the world in the same period.[40] Unfortunately, there is no outcome analysis of this big data. The future Indian eye care cannot afford to let go these opportunities that would provide population estimates of vision loss, eye diseases, eye health disparities, and barriers/facilitators to care. It is necessary to introduce (possibly enforce) EHR at every level of care. These data irrespective of the care provider status (public or private) must be collected centrally and analyzed with due regard to individual and collective privacy and confidentiality.

Conclusion

Five factors shall play a crucial role in the future of eye care in India. These are: (1) human resource development and skill-based training, (2) appropriate eye care to all and in all geographic locations, (3) partnership and synergy between public and private eye care providers, (4) use of technology for uniform documentation, big data collection, and analysis, and finally (5) India centric innovation and translational research.

One such example was the World Bank assisted Cataract Blindness Control Project in India.[41] This project operational between January 31, 1995 and June 30, 2002 had the objectives to upgrade the quality of cataract surgery, expand the coverage of NPCB, reduce blindness in 7 states that accounted for 70% of cataract blindness, remove backlog by performing 11 million cataract surgery, and infrastructure strengthening with financial and technical assistance. At the end of the program and an expense of USD 135.7 million, 15.3 million cataract surgeries were performed, 842 ophthalmologists were trained, many facilities (45 medical colleges, 259 district hospitals, 3,281 primary centers) were equipped with modern instruments (600 slit lamps, 821 A-scans, 681 keratometers, and 128 YAG lasers), and most importantly the mass cataract surgery shifted from “camps” to “fixed” facilities.[42] A record of 30 large non-government organizations participated in this massive program that had the greatest return of investment. A dramatic, yet unforeseen, outcome was the expansion of manufacturing capacity of high-quality ophthalmic devices and suture material for surgery. Over the years this has helped India improve the CSR and cataract surgical coverage, and provide eye care at an affordable cost. This project amply demonstrated that human workforce development must match the infrastructure development, and that participation of like-minded non-governmental organizations is necessary for ultimate societal benefit. Equally significant is an important policy change by the NPCB of empowering the state administration for qualitative and quantitative improvement in implementation of eye care programs in the county.

This is the time for India to reimagine the eye care.

Financial support and sponsorship

Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation, Hyderabad, India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tripathy K. Prof Lalit Prakash Agarwal (1922-2004)-the planner of the first-ever national blindness control program of the world. Ophthalmol Eye Dis. 2017;9:1179172117701742. doi: 10.1177/1179172117701742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 01]. Available from: http://www.foorec.com .

- 3.Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition. A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1971;49:509–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olshansky SJ, Ault AB. The fourth stage of the epidemiologic transition: The age of delayed degenerative diseases. Milbank Q. 1986;64:355–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frenk J, Bobadilla JL, Stern C, Frjka T, Lozano R. Elements for a theory of the health transition. Health Transit Rev. 1991;1:21–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosely WH, Jamison DT, Handerson DA. The health sector in developing countries: prospects for the 1990s and beyond. Ann Rev Public Health. 1990;11:335–8. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.11.050190.002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anjana RM, Ali MK, Pradeepa R, Deepa M, Datta M, Unnikrishnan R, et al. The need for obtaining accurate nationwide estimates of diabetes prevalence in India – Rationale for a national study on diabetes. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:369–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Profile. Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. Directorate General of Health Services. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 9. [Last accessed on 2018 May 02]. Available from: http://www.npcb.nic.in .

- 10.Dandona L, Dandona R, Naduvilath TJ, McCarty CA, Nanda A, Srinivas M, et al. Is current eye-care-policy focus almost exclusively on cataract adequate to deal with blindness in India? Lancet. 1998;351:1312–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Universal Eye Health. A Global Action Plan 2014-2019. WHO Publication. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourne RR, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, Das A, Jonas JB, et al. Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e888–e897. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flaxman SR, Bourne RR, Resnikoff S, Ackland P, Braithwaite T, Das A, et al. On behalf of the vision loss expert group. Global cause of blindness and distance vision impairment 1919-2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e1221–1234. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5. [doi: 10.1016/52214-109x(17) 303393.5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramke J, Gilbert CE. Universal eye health: Are we getting closer? Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e843–4. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao GN, Khanna RC, Athota SM, Rajshekar V, Rani PK. Integrated model of primary and secondary eye care for underserved rural areas: The L V Prasad eye institute experience. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:396–400. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.100533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao GN. The Barrie jones lecture-eye care for the neglected population: Challenges and solutions. Eye (Lond) 2015;29:30–45. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das T, Venkataswamy G. Surgical results: Comparison of patients operated in “eye camp” with patients operated in the hospital. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1983;31(Suppl):924–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dandona R, Dandona L. Review of findings of the Andhra Pradesh eye disease study: Policy implications for eye-care services. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2001;49:215–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das T, Venkataswamy G. Social, economic and behavioral determinants of utilisation of cataract surgery in mobile eye camps. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1985;33:273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna RC, Marmamula S, Krishnaiah S, Giridhar P, Chakrabarti S, Rao GN, et al. Changing trends in the prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in a rural district of India: Systematic observations over a decade. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:492–7. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.100560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das T, Ackland P, Correia M, Hanutsaha P, Mahipala P, Nukella PB, et al. Is the 2015 eye care service delivery profile in Southeast Asia closer to universal eye health need! Int Ophthalmol. 2018;38:469–80. doi: 10.1007/s10792-017-0481-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta A. Ophthalmology postgraduate training in India: Stirring up a Horner's nest. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:433–4. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_427_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gogate P, Biswas P, Natarajan S, Ramamurthy D, Bhattacharya D, Golnik K, et al. Residency evaluation and adherence design study: Young ophthalmologists’ perception of their residency programs – Clinical and surgical skills. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:452–60. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_643_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. New Delhi: World Health Organization; 2002. Mid Level Ophthalmic Personnel in South East Asia. SEA-Ophthal-124; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25. [Last accessed on 2018 May 04]. Available from: http://www.jcahpo.org .

- 26. [Last accessed on 2018 May 04]. Available from: https://www.tnmgrmu.ac.in/index.php/affiliated./allied-health-science-courses .

- 27. [Last accessed on 2018 May 04]. Available from: https://www.nationalskillindiamission.in .

- 28. [Last accessed on 2018 May 04]. Available from: http://www.resi.in .

- 29. [Last accessed on 2018 May 04]. Available from: http://www.moorfields.nhs.uk .

- 30. [Last accessed on 2018 May 04]. Available from: http://www.dhrs.uct.ac.za .

- 31.Ray S, Shah I, Nundy S. The research output from Indian medical institutions between 2004- 2014. Curr Med Res Pract. 2016;6:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ledford H. Translational research: The full cycle. Nature. 2008;453:843–5. doi: 10.1038/453843a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts SF, Fischhoff MA, Sakowski SA, Feldman EL. Perspective: Transforming science into medicine: How clinician-scientists can build bridges across research's “valley of death”. Acad Med. 2012;87:266–70. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182446fa3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. [Last accessed on 2018 May 06]. Available from: https://www.a-star.edu.sg .

- 35. [Last accessed on 2018 May 15]. Available from: https://www.serb.gov.in .

- 36. [Last accessed on 2018 May 06]. Available from: https://www.birac.nic.in .

- 37. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.aao.org/iris-registry .

- 38.Parke DW, 2nd, Rich WL, 3rd, Sommer A, Lum F. The American Academy of Ophthalmology's IRIS® registry (Intelligent research in sight clinical data): A Look back and a look to the future. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:1572–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. [Last accessed on 2017 May 29]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/national_eHealth_authority_neha_mtl .

- 40. [Last accessed on 2018 May 06]. Available from: https://www.market-scope.com .

- 41.Jose R, Bachani D. World bank-assisted cataract blindness control project. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1995;43:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. [Last accessed on 2018 May 13]. Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/archive/website01291 .