Abstract

Introduction

A recognised complication of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is postoperative haematoma, which can threaten the airway. Previous studies have looked at medical methods of preventing this complication. This study aims to evaluate the impact of simple direct pressure postoperatively on the development of haematoma.

Materials and methods

From 2011 to 2016, 161 consecutive CEA were performed by a single surgeon or trainee under supervision. After 80 operations, the postoperative technique was altered, with additional pressure being applied by the surgeon to the skin incision from completion of suturing until each patient was awake in the recovery room. The rates of postoperative haematoma and other complications were compared between the pre- and post-intervention groups, as well as grade of surgeon, urgency of operation and antiplatelet/anticoagulant use.

Results

Post-carotid haematomas were eliminated in the post-intervention group (0/81); in the pre-intervention group 7/80 patients developed haematoma (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in urgency of surgery, antiplatelet/anticoagulant use, grade of surgeon or other complications (stroke: 2/80 vs 0/81 P < 0.05), suggesting that this was not a learning curve effect.

Discussion

The results suggest that applying direct pressure helps to reduce oozing, provides time to monitor and identify additional bleeding and protects the wound from excessive strain that may be caused by coughing while the patient wakes up. We advise that the lead surgeon should apply such pressure to ensure precise and focal targeting, for maximum effect.

Conclusion

During recovery from CEA, focused and prolonged pressure by the operating surgeon is a highly effective method of reducing haematoma.

Keywords: Carotid endarterectomy, Haematoma, Direct pressure

Introduction

Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is a surgical procedure used to remove atherosclerotic plaque from the carotid artery following arteriotomy. It is highly effective in helping to prevent the development of strokes, transient ischemic attacks (TIA) and reducing mortality rates among patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis of 50–99%.1

The New York Carotid Surgery Study in 2007 found that minor postoperative complications could occur in 10% of all cases of CEA.2 Common complications include cranial nerve palsies, wound infections, respiratory obstructions, unstable angina, pulmonary oedema and, most commonly, wound haematomas.3 A potentially avoidable complication, postoperative haematomas increase the risk of infection, wound breakdown, fistulae and tracheal and oesophageal obstruction.4 The prevalence of postoperative haematoma varies between studies from 3.4% to 12%.5,6 Reducing the risk of this complication will facilitate postoperative recovery.

While medical therapies to effect perioperative bleeding risks have been studied,7–10 the use of direct compression of the closed operative wound site has not been previously documented. This study evaluates a protocol of applying direct pressure at the closed skin incision site postoperatively to reduce bleeding and haematoma development. The use of direct pressure for haemostasis is commonly adopted in emergency medicine. This technique uses the simple physiological principle that increased external pressure promotes haemostasis by decreasing transmural pressure and blood flow in vessels.11 The aim of this study is to retrospectively analyse the rates of complications before and after the introduction of this intervention.

Materials and methods

Data were collected retrospectively on all CEAs performed at one centre between June 2011 and October 2016. CEA were performed under general anaesthesia with a carotid shunt and Dacron patch in all cases. For elective carotid endarterectomy (ECE), antiplatelets and anticoagulants were stopped at 2 weeks and 5 days before surgery, respectively. A single dose of 75 mg clopidogrel was administered the evening before surgery. For rapid-access carotid endarterectomy (RACE), anticoagulants were reversed and antiplatelets continued. Prophylactic enoxaparin was used perioperatively for all patients.

In May 2014, after 3 years of performing CEA without wound compression, the addition of direct pressure to the closed skin incision postoperatively was implemented. This was commenced at completion of wound closure and maintained by the operating surgeon during reversal of anaesthesia and during transfer of the patient from the operating table to the recovery room, until the patient was extubated, awake and had ceased coughing. If the surgeon was unable to maintain this pressure personally, the pressure was delegated to a recovery nurse with clear instructions as to where to press over the carotid patch.

Postoperative complications were detected by medical staff and were assessed for severity. Large haematomas that were expanding or threatened the airway necessitated a return to theatre. Smaller haematomas were observed and managed nonoperatively.

Data were analysed on a standardised pro forma by medical staff, collated and divided into subgroups on Microsoft Excel 2011. Chi square analysis was applied to evaluate the difference between the groups. No ethical approval or funding was required for this study.

Results

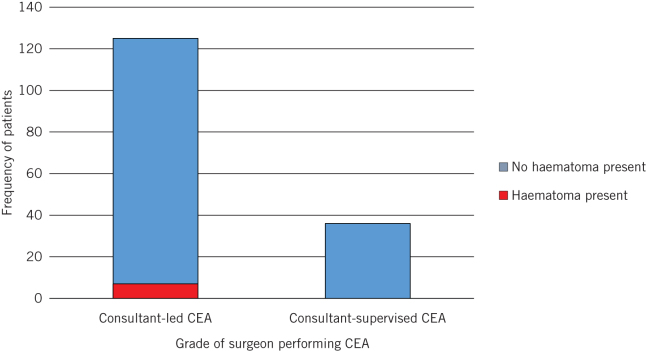

Use of localised pressure surgical technique

Eighty CEAs were performed in the pre-intervention group compared with 81 in the post-intervention group. Of the pre-intervention group, seven patients developed haematomas compared with zero patients in the post-intervention group. The incidence of haematoma development post-CEA showed a marked decrease from 8.64% to 0%; this difference is statistically significant (P = 0.0065; Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Incidence of haematomas before and after changes in surgical technique (P = 0.0065)

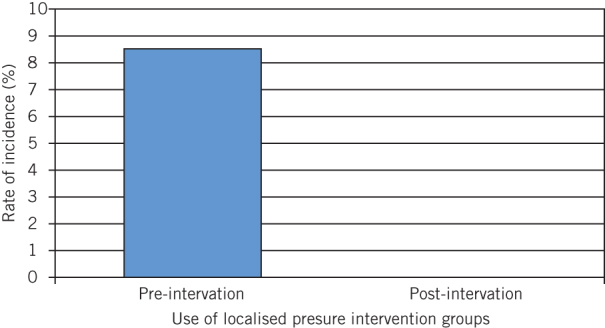

Other complications

Cranial nerve injury was the second most frequent complication observed after postoperative haematomas. In the pre-intervention group, four patients presented compared with this complication and three in the post-intervention group. This difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.7196). The development of other complications such as TIA, stroke and hoarse voice also showed no statistically significant difference between the pre- and post-intervention groups (P = 0.3672, P = 0.4969 and P = 0.6203, respectively; Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Incidence of other complications, cranial nerve injury, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), stroke and hoarseness of voice before and after change in surgical technique, (P = 0.7196, P = 0.3672, P = 0.4969 and P = 0.6203, respectively)

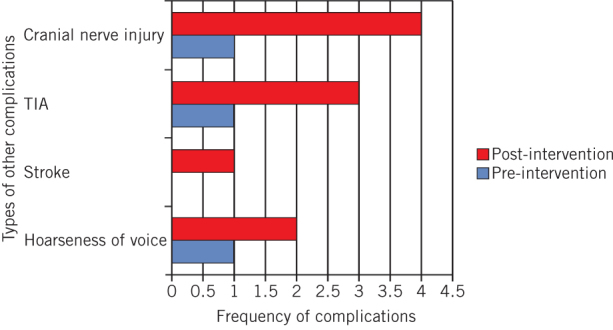

Grade of surgeon

CEA was performed by either the lead consultant or a registrar under supervision of the lead consultant. Seniority of operating surgeon was studied to establish the presence of any ‘learning curve effect’. The results showed that the consultant CEA group had seven haematomas, compared with zero in the consultant-supervised group (P = 0.3479; Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Frequency of patients developing haematomas with consultant-led and consultant supervised carotid endarterectomy (CEA) (P = 0.3479)

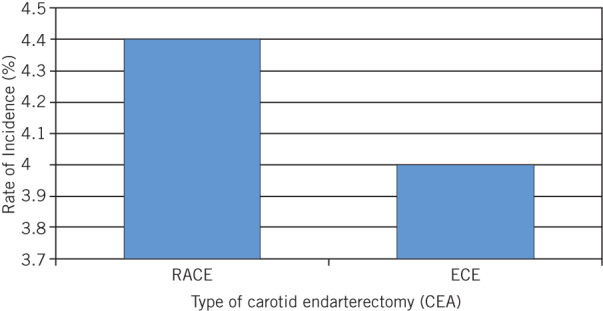

Urgency of procedure

RACE and ECE were compared to assess whether urgency of procedure affected postoperative haematoma development. One patient in the ECE group and six patients in the RACE group developed haematomas across 25 and 137 procedures, respectively. This result was not statistically significant (P = 1.000; Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Incidence rate of haematoma formation in rapid-access (RACE) and elective (ECE) carotid endarterectomy procedures (P = 1.000)

Discussion

These results suggest that the use of direct pressure at the closed skin incision during the immediate postoperative period significantly reduces the risk of postoperative haematomas following CEA. This study shows that direct wound pressure allows the advantages of antiplatelet therapy on reducing stroke rates, without the increased risk to stroke incidence of using protamine to reduce postoperative bleeds.

Previous studies have aimed to minimise haematoma formation following CEA by investigating the effects of both pharmacological and practical interventions. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant use has been studied. The updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines, published in 2011, state that patients should be treated with low-dose aspirin perioperatively and, although clopidogrel monotherapy can be safely continued without an increased bleeding risk, its administration should be individualised per patient.12 The effectiveness of administering single or dual antiplatelet therapy is debatable. Research following the publication of the guidelines has found clopidogrel to be significantly associated with increased postoperative bleeding and reoperation. While dual therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel has in some instances been proven to reduce recurrent neurological events and spontaneous embolisation prior to CEA, meta-analyses have ultimately found perioperative dual antiplatelet therapy to increase neck haematomas significantly.13–15 Other medical treatments have been researched for their impact in reducing haematomas. Protamine sulphate, a heparin reversal agent, has been found to decrease the incidence of wound haematomas significantly, but it may predispose patients to increased thrombosis and stroke risks.11–14 The timing of surgery can impact the rate of complications. Nordanstig and colleagues identified that RACE performed within 48 hours presented a higher risk of complication compared with ECE performed within 2–14 days of diagnosis for symptomatic carotid artery stenosis.16,17

Kunkel et al.18 studied the prevalence of carotid haematomas requiring evacuation in a series of 596 cases. Despite the use of postoperative protamine, they reported a haematoma rate of 2.5%, and that capillary oozing was responsible in 80% of haematomas. This reflects the common experience when re-exploring a neck for post-CEA haematoma when it is unusual to find a source of bleeding such as the carotid artery or jugular vein. We would suggest that direct pressure reduces the capillary oozing that occurs during recovery from anaesthesia, which is exacerbated by coughing, straining and fluctuations in blood pressure.19 We are conducting a further study looking for an association between post CEA haematoma and respiratory disease.

The lack of any significant difference in the incidence of postoperative haematomas between consultant and consultant-supervised CEAs, as well as the observation that other complications are not affected by this intervention, suggests that wound pressure has reduced haematoma rates independently of a learning curve effect. However, this study cannot account for the individual experience of the registrar or the level of consultant supervision in each case. The application of wound pressure was supervised by a single surgeon in each case in this study, but the effect of pressure may vary in other hands.

Where previous studies have looked for associations between perioperative antiplatelets, heparin reversal agents and haematoma formation, in this study we standardised the medical therapy to study the effects of pressure alone. All patients received a standard single antiplatelet and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis regimen. Although the historical control group is a potential limitation of this study, we believe the standardisation of surgical technique and perioperative medication allows the benefit of wound pressure to be studied independently of other factors affecting bleeding risk.

Conclusion

The use of direct pressure following CEA in the immediate postoperative period has been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of postoperative haematomas. In this study, the introduction of this simple technique at one centre has changed a common and dangerous complication into a rare one. This technique requires patience from the operating surgeon but should reduce returns to theatre, wound infections and improve patient satisfaction with carotid surgery. Further study might help understand which patients are most at risk of this complication.

References

- 1.Saha SP, Saha S, Vyas KS. Carotid endarterectomy: current concepts and practice patterns. Int J Angiol 2015; (3): 223–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenstein AJ, Chassin MR, Wang J et al. Association between minor and major surgical complications after carotid endarterectomy: results of the New York Carotid Artery Surgery study. J Vasc Surg 2007; (6): 1,138–1,446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munro FJ, Makin AP, Reid J. Airway problems after carotid endarterectomy. Br J Anaesth 1996; (1): 156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palumbo MA, Aidlen JP, Daniels AH et al. Airway compromise due to wound haematoma following anterior cervical spine surgery. Open Orthop J 2012; : 108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doig D, Turner EL, Dobson J et al. Incidence, impact, and predictors of cranial nerve palsy and haematoma following carotid endarterectomy in the international carotid stenting study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014; (5): 498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Self DD, Bryson GL, Sullivan PJ. Risk factors for post-carotid endarterectomy haematoma formation. Can J Anaesth 1999; (7): 635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fearn SJ, Parry AD, Picton AJ et al. Should heparin be reversed after carotid endarterectomy? A randomised prospective trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1997; (4): 394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treiman RL, Cossman DV, Foran RF et al. The influence of neutralizing heparin after carotid endarterectomy on postoperative stroke and wound haematoma. J Vasc Surg 1990; (4): 440–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbaum A, Rizvi AZ, Alden PB et al. Outcomes related to antiplatelet or anticoagulation use in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Ann Vasc Surg 2011; (1): 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kakisis JD, Antonopoulos CN, Moulakakis KG et al. Protamine reduces bleeding complications without increasing the risk of stroke after carotid endarterectomy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2016; (3): 296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelligra R, Sandberg EC. Control of intractable abdominal bleeding by external counterpressure. JAMA 1979; (7): 708–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricotta JJ, Aburahma A, Ascher E et al. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J Vasc Surg 2011; (3): e1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batchelder A, Hunter J, Cairns V et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy prior to expedited carotid surgery reduces recurrent events prior to surgery without significantly increasing peri-operative bleeding complications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015; (4): 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morales Gisbert SM, Sala Almonacil VA, Zaragoza Garcia JM et al. Predictors of cervical bleeding after carotid endarterectomy. Ann Vasc Surg 2014; (2): 366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barkat M, Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of dual versus single antiplatelet therapy in carotid interventions. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2017; (1): 53–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rix TE, Singh I, Insall R, Senaratne J. RACE to protect brains. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010; (8): 647–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordanstig A, Rosengren L, Stromberg S et al. Very urgent carotid endarterectomy is associated with an increased procedural risk: the carotid alarm study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2017; (3): 278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunkel JM, Gomez ER, Spebar MJ et al. Wound haematomas after carotid endarterectomy. Am J Surg 1984; (6): 844–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pazardzhikliev DD, Yovchev IP, Zhelev DD. Neck haematoma caused by spontaneous common carotid artery rupture. Laryngoscope 2008; (4): 684–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]