Over time, wars and disasters have increasingly targeted or involved civilian populations. At the end of 2005, the global figure of “persons of concern” (including refugees, returnees, stateless, and internally displaced persons) stood at 21 million. By the close of 2006, the number stood at 32.9 million, an increase of 56%. At the time of this writing, the estimated number of refugees alone stands at 9.9 million, the highest in 5 years [1].

Each individual refugee has a unique story of development, culture, preflight, flight, and resettlement. Literature shows that refugee populations experience a wide range of stressors such as lack of care, witnessing murders or mass killings, forced labor, lack of food, forced combat, rape, and/or torture [2–4]. Other major experiences include loss or separation of family, friends, culture, and possessions [5–8].

Many reviews and studies have been published on the mental health status of refugees [9–12]. Literature clearly links the stressful experiences of a refugee to increased risk for many mental health issues [13–16]. A large number of studies specifically have measured trauma symptoms, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), although methods and estimates vary [7,16,17]. Youth refugee populations present with not only PTSD but also with depression, anxiety, and grief issues [6,18–22]. Comorbidity of depression, anxiety, and PTSD is very common [4,23]. The mental health symptoms of young refugees span further to include conduct disorder, social withdrawal, restlessness, irritability, difficulty with relationships, and attention problems [24–26].

In summary, refugee children and adolescents may present with a myriad of symptoms after their traumatic experiences. This diverse clinical presentation requires a treatment model that is able to mitigate a number of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Refugee populations also require interventions that can adjust to the wide-ranging experiences probably encountered during the phases of preflight, flight, and resettlement.

Considerations in the treatment of refugee youth

In working with populations as complex and varied as refugees, some important considerations are involved around “treatment.” First, the unique experiences of refugee populations often put them in need of services on many levels (eg, legal, occupational, educational, social, and individual). Frequently refugee families choose not to seek mental health services until basic needs have been met [27–29]. There is some evidence that immigration stressors or social stressors, such as discrimination, are associated with PTSD symptoms in refugee youth [15,30]. Therefore refugee youth may benefit from multiple levels of services, ideally integrated [31,32]. The focus of this article is on the mental and behavioral health component of services for refugee youth.

Second, it is important to recognize the resiliency of youth. Research clearly demonstrates that not all children who experience trauma, including multiple horrific experiences, show mental health symptoms or problems in functioning [33]. Another proportion of such a population may be mildly symptomatic, perhaps benefiting from support programs or efforts to bolster pre-existing support systems. Finally, a proportion will show significant trauma symptoms and need therapeutic treatment. In this article, which discusses treatment using cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the focus is on children experiencing trauma-related symptoms.

Finally, with all clients who have experienced trauma and especially refugee populations, engagement is critical to therapeutic treatment [34–37]. One of the hallmarks of trauma symptomatology is avoidance, which increases the challenges of engagement in therapy and maintaining attendance. In addition, for many refugee youth and families, the process of therapy itself may be alien. Families may have different explanatory models of illness and associated pathways to healing, such as understanding the child’s problems in religious, rather than psychologic, terms [38]. Speaking to a relative stranger about personal issues may seem strange and undesirable. Families may be particularly hesitant to talk to a therapist from a different culture or think that using mental health services means they are “crazy.” Research suggests that engagement strategies are needed early on and throughout treatment with youth and families and also with key members of the cultural community [38]. Engagement strategies may include making sure practical assistance is offered or that families are linked up with other levels of service, as mentioned previously. Finally, delivering services within service systems that are trusted and accessed by refugee youth, such as school settings, may increase acceptance of and engagement in treatment.

Empirical literature on treatment of refugee youth

The literature on empirically tested mental health treatments of youth refugees is weak [39]. Much of the published material on clinical interventions includes descriptive reports, case studies, or small cohort studies without control groups [40–42]. For example, various holistic or family interventions have been used with refugee populations but are lacking empiric evaluation [28,43–49].

CBT with refugee populations contains some empiric evaluation, much of which is covered in other articles in this issue. For example, Layne and colleagues [50] investigated the use of a school-based trauma- and grief-focused psychotherapy manual with 55 war-exposed Bosnian youth. This and other studies using the same manual (C.M. Layne, W.S. Saltzman, N. Savjak, and colleagues, unpublished manual, 2001) are covered in another article in this issue [51,52]. A different CBT model [53] was used by Ehntholt and colleagues [54] in a controlled study with 26 refugee youth in a school, compared with wait-list control. Another group of researchers has adapted narrative exposure therapy (NET), which is a combination of CBT and testimonial therapy, for youth (KIDNET) [55–57]. Although the empiric evaluation of therapeutic treatments for traumatized refugee youth is limited, studies such as these are showing that CBT-based interventions are promising for refugee populations. This is not to say that other treatments are not effective but rather that CBT interventions currently have the greatest empiric support.

Empirical literature on cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of child trauma

CBT for PTSD has been evaluated quite extensively in nonrefugee youth [51,58–61] and is considered one of the most efficacious and well-supported interventions for traumatized youth. There has been a growing research literature testing the efficacy of mental health interventions with traumatized child populations, and some recent reviews have examined varying levels of empiric support [33,62–64].

Three individual-focused CBT treatment models for traumatized youth have been evaluated in randomized, controlled trials: trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT), cognitive-based TF-CBT, and Seeking Safety. TF-CBT has been tested systematically and rigorously by the developers, mainly with sexually abused youth. Various randomized, controlled studies have shown that TF-CBT is superior to treatment-as-usual and to nondirective supportive therapy in reducing PTSD, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and maintaining these results [65–70]. A multisite randomized, controlled trial with 229 sexually abused children showed statistically significant improvements with TF-CBT in comparison to client-centered therapy [59]. These studies also demonstrated that TF-CBT is effective with other trauma symptoms such as interpersonal trust, perceived credibility, and shame, and that caregivers involved in TF-CBT reported greater improvements in their own mental health. Many of these studies included multiply traumatized children, cross-cultural populations, and children who had complex PTSD. An independent researcher also completed a randomized, controlled trial showing TF-CBT to be superior to a wait-list control condition in improving PTSD and depressive symptoms in sexually abused children [71].

Cognitive-based TF-CBT has been tested in a pilot randomized, controlled trial involving 24 children exposed to single-incident traumatic events [72]. Compared with a wait-list control condition, CBT showed large effect sizes for PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Seeking Safety [73] is a treatment model developed for comorbid PTSD and substance use disorder. It was designed originally for adults and has been evaluated recently in a randomized, controlled trial involving 33 adolescent girls [74]. Compared with treatment- as-usual, those receiving Seeking Safety showed significantly better outcomes in a variety of domains.

Other CBT models for trauma with completed randomized, controlled trials have been developed specifically for school-based work. Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) [75] has been tested using a quasi-experimental design with recent immigrant students and in a randomized, controlled trial with sixth and seventh graders who were exposed to violence, showing significant reductions in PTSD and behavioral symptoms [76,77]. Multimodality Trauma Treatment was shown to decrease trauma-related, depressive, and anxiety symptoms in 14 students [60], and these effects have been replicated in additional studies [78]. The UCLA Trauma/Grief Program was tested on 26 students and showed reductions in PTSD and grief symptoms but not in depression [79]. Classroom-Based Intervention [80] was developed specifically for disasters or ongoing terrorist threat. Preliminary evaluations following an earthquake in Turkey and in the West Bank/Gaza schools and camps for Palestinian refugees have shown improvements on multiple domains [81].

Although these CBT models have the most empiric evidence, there are many other promising treatments for traumatized youth. For example, Trauma-Systems Therapy is a program that integrates CBT components with services to stabilize the child and/or family environment and to advocate on the child’s behalf. An open trial of Trauma-Systems Therapy in 110 children demonstrated significant improvement in PTSD symptoms [82]. Trauma-Systems Therapy has been adapted but not yet evaluated for use with refugee youth.

Empirical literature on treatment for traumatic grief

Critical to refugee populations is the issue of loss and traumatic grief. Most of the treatment models already discussed have integrated components focused on loss, although few have been separately evaluated. TF-CBT [83] has been adapted for use in traumatic grief cases, with some initial data on the distinct effectiveness of the traumatic grief components. The 16-session CBT-child traumatic grief (CTG) model was tested with children 6 to 17 years old who had lost parents or siblings [84]. Results demonstrated that significant improvement in PTSD symptoms and adaptive functioning occurred only during the trauma-focused treatment module (the first eight sessions) of this protocol, whereas CTG improved significantly during both the trauma-focused module and the grief-focused module (the second eight sessions) of the protocol. Another study modified CBT-CTG by decreasing the grief module from eight to four sessions and tested its effectiveness on 39 youth. Results demonstrated that children significantly improved in CTG, PTSD, depression, and anxiety [85]. These two studies, combined with other CTG and adult complicated grief studies [50,86,87], suggest that CTG may be a unique condition consisting of a combination of posttraumatic and unresolved grief symptoms. This literature also suggests that CTG may require sequential trauma- and grief-focused interventions. Because so many refugees are likely to suffer from combinations of trauma and grief, interventions that include both foci may be particularly promising.

Evidence beyond the laboratory

Although many treatments have demonstrable efficacy within randomized, controlled trials, there are far fewer rigorous trials on the delivery of therapies under conditions of routine practice, where issues such as greater diversity of clients, delivery by front-line practitioners or even paraprofessionals, and comorbidity are common [88,89]. The transportability and flexibility of an intervention are important considerations when working with diverse and complex populations. Effectiveness studies have been conducted for some of the interventions mentioned previously. For example, TF-CBT [83] and the Trauma/Grief Program (C.M. Layne, W.S. Saltzman, N. Savjak, and colleagues, unpublished manual, 2001) were used in a large effectiveness study of multiply traumatized and culturally diverse children across nine sites in New York City after the September 11 disaster. Results showed significant improvements in mental health symptomatology [90]. TF-CBT also has been adapted and used with several populations including Hispanics [91], Australians [71], and refugees of African descent [92], with evidence suggesting that TF-CBT maintains its effectiveness with adaptation. Layne and colleagues [50] trained paraprofessionals in Bosnia to implement their Trauma/Grief Program. In addition, the adult version of Seeking Safety has shown successful transportability to diverse cultures including Spanish-speaking adults, female veterans, and prison populations. Such studies suggest that these interventions are adaptable to different cultures, are transportable in regards to training and implementation, and remain effective in less-than-ideal conditions.

Description of cognitive behavioral therapy

Trauma-focused CBT interventions for youth are based on well-established theories and components initially developed for the treatment of fear and anxiety in adults [93,94] and commonly used with traumatized adults [95,96]. Components often are similar to CBT treatments applied to many problems, such as depression and anxiety, in children and adolescents [97–100]. The sharing of components across disorders makes sense, given the myriad of symptoms with which youth who have experienced trauma may present. Although the similarities are many, each evidencebased treatment may have a particular system, order, and application of the components. Because CBT is largely skill-based, components tend to build on one another and help prepare the child for future components.

The acronym “PRACTICE,” explained in Box 1, is helpful in listing the components most often seen in CBT models for traumatized youth.

Box 1. The “PRACTICE” acronym for common components of cognitive behavioral therapy for traumatized youth.

P – Psychoeducation and parenting skills

R – Relaxation

A – Affective modulation

C – Cognitive processing

T – Trauma narrative

I – In vivo desensitization

C – Conjoint child/parent sessions

E – Enhancing safety and future skills

Clinical work with refugees is often done through a phased approach [101] that includes (1) establishing safety and trust, (2) trauma-focused treatment, and (3) reintegration. The first phase of establishing safety and trust encompasses the first four components (“PRAC”) from the “PRACTICE” acronym. In this phase it is not necessary to obtain information about the traumas immediately or to discuss them directly. Refugee youth often assume mistakenly that they should or need to give their trauma stories immediately in treatment. Different models, however, have varying numbers of sessions before exposure or narrative work, some with very few and others with added components such as stabilization.

The following sections briefly review the goals or foci of each component and how they might be implemented with refugee populations based on ongoing work with refugee populations (B.H. Ellis, L. Murray, and D. Hunt, personal communication, 2007) [102].

Psychoeducation and parenting skills

Psychoeducation

Some of the first objectives of psychoeducation are to engage, normalize, and validate. With refugee families, it may be helpful to begin by providing information to the family about the role of the therapist and what mental health treatment looks like. Some families may assume that mental health services are reserved for only the severely mentally ill or that the therapist is part of a social services department that may take their child away. In addition, eliciting information from the family about how they understand the child’s problems may be useful for planning how to present material in the course of treatment. For instance, the cognitive triad may need to be introduced more slowly and with additional explanation if a family views a child’s problems as the result of a spirit jinx and not something that the individual may readily influence or change.

It is important to let refugees and their families understand that widely ranging reactions to stressful experiences are normal. Within some cultures, symptoms may be expressed somatically. It may be helpful to give the youth and caregivers information about some common reactions and to link these reactions to areas of clear value to families. For instance, some families may place less emphasis on children’s emotions but may value school success highly. Providing concrete information about how trauma can affect a child’s ability to engage in and learn at school may help parents see the value in mental health care.

Another goal of psychoeducation is to instill hope that the patient can feel better. Sometimes it is helpful for a clinician to let the youth know that they have seen other refugees like them improve. A central feature of CBT is safety and building safety skills, with some models integrating this component more extensively [74]. This aspect is woven throughout the treatment components but also should be addressed immediately. For example, refugee youth from different cultures may not be familiar with confidentiality and limits of confidentiality. These considerations should be reviewed and explained as being activated solely as a concern for the patient’s safety. Some refugee youth continue to be exposed to trauma, such as neighborhood violence, after resettlement, so it is also essential to assess current safety and to follow up on any immediate safety concerns. It may be important to review general safety issues such as (1) when it is safe to go out in their neighborhood or community, (2) who is a “safe person” in their life right now, and/or (3) a safety plan if they ever feel unsafe.

A final goal of psychoeducation with the TF-CBT model is to present a treatment plan, clearly laying out how many weeks the program will last and what will be done throughout that time. As with most CBT treatments, this plan should convey a spirit of upfront honesty about what the patient will experience during treatment. This aspect is particularly important when working with populations to whom the idea of “therapy” may be quite foreign. Describing a plan and a timeline also helps assure youth and caregivers, takes away any fears of the unknown, and promotes attendance.

The clinical implementation of psychoeducation can vary widely. With some refugee populations, drama or skits may allow the client to demonstrate how they have seen stress reactions expressed in their community [102]. Different techniques work for different individuals, and clinical as well as cultural judgment should be used to decide on the most appropriate technique.

Parenting skills/psychoeducation for caregivers

It is well known that many refugee youth lose their parents, many are orphans, many live with relatives, and some are completely without any caregiver or family. In this respect, it is important to remember many CBT treatments have been shown to be highly effective even without the involvement of a caregiver [50,65,75]. If a caregiver is involved, treatment is explained as a collaborative process in which the caregiver is “the expert on this child.” Within some cultures parents may be accustomed to withholding their opinions or ideas out of respect for the professional with whom they are working. CBT treatments view caregivers as central therapeutic agents of change and include them in treatment because they can be a child’s strongest source of healing [65,67,69]. This “collaboration” also helps incorporate appropriate cultural issues with which the therapist is unfamiliar. Another goal of psychoeducation is to empower a caregiver to feel capable of providing support for the youth. Communicating to parents that treatment is meant to support the family, and not to undermine parenting practices or authority, is essential.

Often CBT treatments that include caregivers spend some time on parenting skills. The basic goals are to enhance enjoyable caregiver–child interactions and to maximize effective parenting. Before incorporating this component with refugees, it is critical to understand what type of parenting is culturally supported and valued. For example, in the West parents often are taught to “praise” their children for specific behaviors they do well. In other cultures, this behavior may be referred to more softly as “encouragement,” or the behaviors that caregivers praise may be different. With caregivers of orphaned refugees, skills may focus on building an attachment with the child. Parenting skills are presented as needed in a family and are incorporated throughout the treatment, rather than devoting multiple full sessions to this component alone.

Relaxation or stress management

The goal of relaxation is to explain the physiologic reactions to stress and to teach techniques to reduce these reactions. People relax in assorted ways, such as taking a walk, talking to a friend, meditating, praying, reading a book, or exercising. It may be necessary to ask children how those around them or in their culture seem to relax. For example, some African populations see traditional dances or singing as relaxing but may not be familiar with meditation. Finally, with refugee youth, it may be important to talk about situations or times when it is appropriate to relax and times that it may not be as safe.

Affective modulation

The first goal of affective modulation is for the clinician to understand the child’s vocabulary for different feelings. The child’s emotional vocabulary may be shaped by linguistic ability, as in the case of a child who has relatively few emotion words in English but many in his or her own language, or by culture, as in the case of a child whose native language has different means of describing emotions. When there are language barriers, engaging a cultural broker or a bicultural therapist may be important. In addition, drama or making faces that represent certain feelings for the child may help overcome mild language barriers. When culture shapes a child’s emotional vocabulary, more extensive care is needed to ensure that therapist and child have a common language. For example, a refugee child may use a local word for a feeling that means “deep within the soul,” a word that does not exist in English. As another example, Somali language has relatively few words for emotions but conveys very nuanced emotional experiences through poetry. In these examples the child’s emotional vocabulary may be quite rich if the therapist is able to understand how emotions are talked about or communicated in the child’s culture. It also is helpful for a clinician to understand the identified feelings from a number of viewpoints, including (1) an example of the situation to which the feeling is linked, (2) where the child might feel a particular emotion in his/her body, and (3) the intensity of a particular feeling word. A clinician also might link identified feelings with another “language” (eg, colors, animals, plants, food, cars, sport). This linking can help if talking about feelings is difficult or when there are language challenges. For example, if traditional dancing or poetry was used in a previous component, a clinician might want to suggest using different dances or poems to represent different feelings.

Cognitive coping skills or the cognitive triad

The first goal of the cognitive coping skills component is to help children distinguish among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. With refugee youth, it is important first to understand what they think thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are and where in the body thoughts, feelings, and behaviors originate. For example, some children may say thoughts come from the head; others, depending on their cultural background, may say they come from the heart. Some explanatory models may be quite different from the cognitive triad (eg, a child may have been told that his or her behaviors are a result of being jinxed). Some cultures do not draw a distinction between mind and body. Taking a mutually respectful stance and encouraging youth to try out a new way of thinking without undermining cultural beliefs may help in these situations.

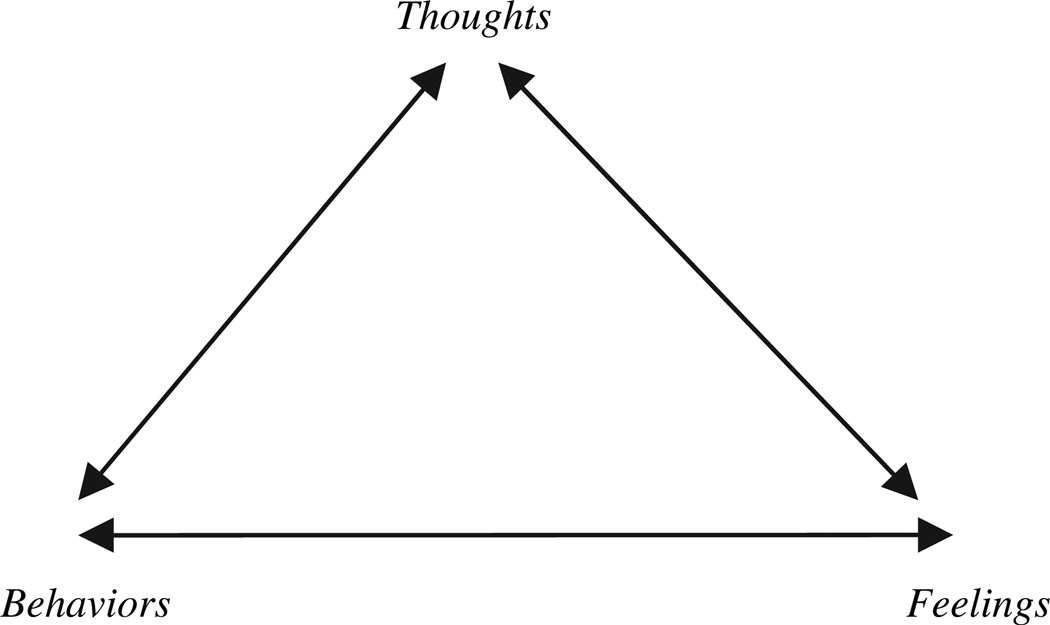

The second goal is to help youth make the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as they relate to everyday life. At first, the situations used should be familiar to the child and should be benign, such as sharing a meal. These goals usually are accomplished by drawing a triangle (Fig. 1), but there are many other creative ways to also achieve these objectives. For example, some refugees may not be familiar with shapes, and a clinician might chose to use a drawing of a body to connect “things that go on in our heads” with “feelings inside us,” and “actions that our body does.” Once a youth understands the connection, the objectives are to help the patient recognize that negative feelings often originate from inaccurate or unhelpful thoughts [103] and work to view different events in more accurate or helpful ways. Again, these skills should be taught in the context of everyday events and not necessarily around any traumatic experiences. As the child becomes familiar with these skills, they can serve as a tool to work through different crises that may arise between sessions.

Fig. 1.

The cognitive triangle.

Summary of skills

By accomplishing the goals of the first four components (“PRAC”), the clinician has given the youth skills that will be used throughout the creation of the trauma narrative. In addition, the clinician should have learned about the client, including aspects of the client’s culture, what relaxation techniques work for the client, how he or she best communicates about emotions, what his or her interests are, what everyday life consists of, and what types of helpful or “unhelpful” cognitions the client may have. Depending on cultural, linguistic, and engagement barriers, accomplishing the “PRAC” goals may take more time for some children than others. Especially when refugees have been deliberately harmed by authority figures, establishing trust with a therapist who holds a position of relative power may take extra time. For refugee youth, moving to the trauma narrative portion of treatment should take place only after the necessary skills and trust are in place. When done in a culturally sensitive manner, the components of PRAC can be a remarkable way to bond and build trust with someone while simultaneously teaching skills.

Trauma narrative

Directly talking about the trauma is a technique that some avoid when working with traumatized children. One reason for this avoidance may be caregiver or youth discomfort in talking about the trauma. Others may be nervous about “pushing the child,” or further traumatizing the child. Most CBT interventions developed for youth conceptualize the trauma narrative as a slow process in which the clinician is more of a guide, allowing the unspeakable to be spoken. Contrary to a belief that telling the narrative may further traumatize a youth, it actually allows a child to gain mastery over trauma reminders or triggers, to resolve avoidance symptoms, and to correct distorted or unhelpful cognitions. Extensive literature demonstrates that exposure treatment is effective with a variety of anxiety-related treatment [59,95,104].

The trauma narrative usually is created in the form of a book but can also be expressed in other creative ways such as a poem, song, dance, interview, or computer presentation. For refugee populations that are likely to have experienced a host of traumatic experiences, completing a timeline is helpful. The timeline gives the child an opportunity to write down any experiences he or she believes are important and gives the clinician some perspective on how the youth views those experiences. For each event, a chapter or section may be written. Sections may be about an event (eg, “village invasion”), a time of chronic trauma (eg, “when the rebels kept coming”), important cultural omissions (eg, “the death ceremony that never happened”), or even ongoing instability within resettlement periods (eg, “my first day in the new place,” “the second foster home”). In this way, children are not required to identify a single “worst” event. With each chapter or section, clinicians start the child at a specific point in time to help the client walk through the trauma in a step-wise fashion, with more and more details given. As the story is gone over repeatedly, the child slowly becomes desensitized to the material.

A critical part of the trauma narrative is the cognitive reprocessing work. Once a traumatic event is written about, the clinician asks the youth about thoughts and feelings he or she had at the different points. In this way, it becomes clear where different maladaptive, inaccurate, or unhelpful cognitions may lie. Cognitive restructuring techniques are used to help the child come to a more helpful thought, potentially leading to different (more positive) emotions and behaviors. The trauma narrative is finalized with a section on what the child learned, what he or she might want to tell other refugee children, or how the client is different now.

If a caregiver is involved in a refugee child’s treatment, ideally the trauma narrative would be shared with the caregiver after each session. In this way, a caregiver also is desensitized slowly to the material in the book and also understands more about the thoughts and feelings related to the events. The sharing of the trauma narrative is important so that the child has someone in his or her life who has heard the story and with whom the child is comfortable sharing openly. Often entire refugee families have shared traumatic experiences. Some parents may not be ready to hear their child’s narrative, especially if it describes their own traumatic experiences as well. As with the child, the parent needs to have acquired the skills and established the trust necessary to be a part of sharing the trauma narrative.

In vivo desensitization

In vivo desensitization may not be needed in all cases. If the feared situation or place is distant or the traumatizing stimuli are not accessible, this process may not be possible. There may be situations in which this component, whose goals are to desensitize the child to trauma reminders and resolve avoidance, may be used.

Conjoint parent-child sessions

As described previously, care must be taken not to share a child’s trauma narrative without first ensuring that the caregiver is adequately prepared. If a caregiver is involved and capable of being supportive to the child, there is a joint session to share the trauma narrative. The goals include sharing the trauma narrative, opening communication between caregiver and child, and furthering cognitive reprocessing. For refugee children who may be without a caregiver, this session may be done with any adult with whom the youth is connected (eg, a case-worker, legal aid, camp leader, or teacher).

Enhancing safety skills

Enhancing safety skills is a large component of many CBT trauma programs and occurs throughout the treatment, with the overall goal of preparing for future trauma reminders or safety situations. With refugee populations, this component may include developing safety plans for any of a variety of situations they fear may occur. This component also could entail skills training on other issues such as healthy sexuality, bullying behavior, problem-solving skills, or interpersonal communication skills. Youth who have spent a great deal of their childhood in refugee camps may have developed ways of relating interpersonally that are inappropriate in other cultures, such as using aggression to get one’s needs met. Focusing on social or healthy living skills may be an important way to increase safety and also to provide assistance with non–trauma-related emotional and behavioral needs of refugee youth. Often youth are encouraged to return to their timeline and extend it to the future. This component shares some of the objectives of the final phase commonly used in refugee work, or reintegration.

Components for addressing childhood traumatic grief

In cases of traumatic grief, the “PRACTICE” components often help a child become “unstuck” from trauma symptoms, opening the client up to a more healthy grieving process. The first CTG component is grief psychoeducation. With refugee youth, it is essential to understand how death and mourning are understood by them and their native culture. For example, a clinician might ask the youth to draw a picture of what he or she thinks happens when someone dies [105]. In addition, the clinician should focus on understanding grief reactions the child may be experiencing.

The second component includes grieving or reminiscing about the loss of the deceased or missing, considering both the experiences the child had with that person in the past and the experiences they might have shared in the future. For example, a clinician might ask the child to identify, name, act out, or draw the things he or she did with the deceased or missing person. For refugee children this process may contain mundane situations, rituals, or meaningful places. Talking about the future helps prepare a child for reminders of loss when the deceased or missing person is not present for events and enables the client to create a coping plan (C.M. Layne, W.S. Saltzman, N. Savjak, and colleagues, unpublished manual, 2001). Another goal often includes resolving ambivalent feelings about the deceased or missing person. For example, some refugee youth may have been separated from a loved one suddenly and unexpectedly, with no time for “good-byes.” This abrupt separation may lead to lack of resolution, guilty feelings, resentment, or anger that a child may feel cannot be voiced. A clinician might use the skills taught within the “PRACTICE” components to restructure some thoughts, encourage a child to have a “mental conversation” with the deceased or missing person or the person’s spirit, or to write a letter to the absent person. The goal with refugees would be to guide them through a meaningful and culturally appropriate way of honoring the deceased or missing person and sending that person on.

Additional components help the child shift to the positive and focus on the future. For example, a child may be encouraged to think of positive memories of the deceased or missing person. Some children may put together a memory box or a collage with positive experiences or things about the deceased or missing person. For refugee children, it may be helpful to hold a memorial ceremony for the deceased, especially if there is some cultural ritual that they feel was absent. To focus on the future, a child is encouraged to redefine the relationship with the deceased or missing person and commit to present relationships. With refugees, activities may be used to talk about what they are missing and what they still have in the present. It is particularly important that refugee children be given skills to feel that it is acceptable to move on to other relationships so a support system can be established in the current culture. These two components attempt to address reintegration issues further, similar to a phased approach commonly advocated with refugee populations.

Additional considerations

A number of other considerations should be addressed when working with refugee populations. For example, a clinician often must work through an interpreter because of language barriers. CBT manuals usually are well laid out so translators can become familiar with some of the session material in advance. In some cases, especially when whole communities have been traumatized, participating in the trauma narrative may be emotionally difficult for interpreters. Providing additional training and debriefing for interpreters may be helpful. In some circumstances a cultural brokering model can be developed. Another consideration is that some refugees may not have attended school and thus present with lower cognitive development and often do not have skills such as writing, reading, and drawing. CBT interventions designed for youth (eg, activities done in dramatic rather than written form) are adapted easily to these situations. Another common issue, particularly when working abroad with refugee populations, is the advantage of working in groups (C.M. Layne, W.S. Saltzman, N. Savjak, and colleagues, unpublished manual, 2001) [75]. The model can incorporate moving through the components (particularly the first four “PRAC” components) with multiple youth. Depending on the experiences and safety levels, the trauma narrative sessions might be completed individually.

Summary and future directions

There is a vast literature base showing that refugee youth are likely to encounter numerous and varied traumatic events that can have widely devastating and long-term effects in a range of areas. The resulting symptoms and child/family circumstances are equally diverse, making treatment challenging at best. The empiric evaluation of mental health treatments with refugee youth is increasing but remains weak. The available research with nonrefugee populations suggests that CBT is highly efficacious in treating traumatized youth and the complex myriad of symptoms with which they present. Current efforts are focused on extending these empirically sound treatments into the mainstream, testing their ability to perform under more naturalistic conditions and with culturally diverse populations. Some CBT interventions already have shown significant results with refugee youth populations [50,54,57]. It is likely that many of the CBT treatments rigorously tested with nonrefugee youth (eg, TF-CBT, CBITS) could produce similar reductions in the diverse emotional, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms presented by traumatized refugee youth.

CBT has certain characteristics that may be particularly advantageous in the treatment of refugee youth. For example, CBT treatments are skill-based with the goal of giving children and families the abilities to work through issues beyond the treatment. CBT is theoretically grounded in what has been demonstrated to be effective for trauma symptomatology including its diversity and comorbidity. CBT also is time-limited, increasing the chances for sustainability and commitment from clients. Finally, certain CBT interventions have demonstrated flexibility in how goals are implemented, opening many opportunities for cross-cultural modifications while maintaining fidelity.

The current state of literature on treatment for traumatized youth suggests that the time is ripe to move beyond counting those affected and describing their problems and into evaluating the effectiveness of interventions with young refugees. Overall, there are many promising interventions for refugee youth that could use empiric evaluation and empirically supported interventions for traumatized youth that could be adapted for and disseminated to refugee populations. It will be important to evaluate empirically interventions with children who may be at varying levels of ongoing risk, such as children who have relocated to a safe area versus those who may remain within a camp and/or in a tumultuous zone. For those working with refugee populations who have relocated to Europe or the United States, studies of how cultural adaptations increase acceptance of and engagement in treatment within refugee communities and of the effectiveness of these treatments in improving functioning and the ability to take advantage of other services would be advantageous. For researchers working with young refugee populations in low-resource countries, it will be important to examine the training process, the acceptability of the intervention to the local culture, its cost effectiveness, and its sustainability. Finally, in both countries of resettlement and refugee camps, investigating how CBT and trauma processing can best be integrated with other services and needs could enhance greatly the overall system of care for refugee youth. Although the understanding of how to treat refugee youth effectively is advancing, much work remains to be done.

References

- 1.United Nations High Ccommissioner for Refugees. [Accessed November, 2007]; Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/STATISTICS/4676a71d4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boothby N. Trauma and violence among refugee children. In: Marsella A, Bornemann S, Ekblad J, et al., editors. Amidst peril and pain: the mental heath and well-being of the world’s refugees. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox PG, Cowell JM, Montgomery A. Southeast Asian refugee children: violence experience and depression. Int J Psychiatr Nurs Res. 1996;5:589–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinzie JD, Sack WH, Angell RH, et al. The psychiatric effects of massive trauma on Cambodian children, I: the children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1986;25:370–376. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry JW. Refugee adaptation in settlement countries: an overview with an emphasis on primary prevention. In: Ahearn FL, Athey JL, editors. Refugee children: theory, research and services. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991. pp. 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenbruch M. From post-traumatic stress disorder to cultural bereavement: diagnosis of Southeast Asian refugees. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:673–680. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothe E, Lewis J, Castillo-Matos H, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder among Cuban children and adolescents after release from a refugee camp. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:970–976. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobin JJ, Friedman J. Intercultural and developmental stresses confronting Southeast Asian refugee adolescents. Journal of Operational Psychiatry. 1984;15:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen PS, Shaw J. Children as victims of war: current knowledge and future research needs. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:697–708. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyes EF. Mental health status in refugees: an integrative review of current research. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2000;21:397–410. doi: 10.1080/016128400248013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lustig SL, Kia-Keating M, Knight WG, et al. Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health 1993. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(1):24–36. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rousseau C. The mental health of refugee children. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review. 1995;32:299–331. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Athey JL, Ahearn FL. The mental health of refugee children: an overview. In: Athey JL, editor. Refugee children: theory, research, and services. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almqvist K, Broberg AG. Mental health and social adjustment in young refugee children 31/2 years after their arrival in Sweden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:723–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sack WH, Clarke GN, Seeley J. Multiple forms of stress in Cambodian adolescent refugees. Child Dev. 1996;67:107–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele Z, Silove D, Bird K, et al. Pathways from war trauma to posttraumatic stress symptoms among Tamil asylum seekers, refugees, and immigrants. J Trauma Stress. 1999;12:421–435. doi: 10.1023/A:1024710902534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinzie JD, Boehnlein JK, Leung PK, et al. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and its clinical significance among Southeast Asian refugees. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:913–917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.7.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papageorgiou V, Frangou-Garunovic A, Iordanidou R, et al. War trauma and psychopathology in Bosnian refugee children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9:84–90. doi: 10.1007/s007870050002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Servan-Schreiber D, Lin BL, Birmaher B. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder in Tibetan refugee children. JAmAcad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:874–879. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199808000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsman JK, Leong FTL, Johnson MC, et al. Estimates of psychological distress among Vietnamese refugees: adolescents, unaccompanied minors and young adults. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31:1251–1256. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90132-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nader K, Pynoos RS, Fairbanks L, et al. Apreliminary study of PTSD and grief among the children of Kuwait following the Gulf crisis. Br J Clin Psychol. 1993;32:407–416. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1993.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith P, Perrin S, Yule W, et al. War exposure among children from Bosnia-Hercegovina: psychological adjustment in a community sample. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15:147–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1014812209051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sack WH, McSharry S, Clarke GN, et al. The Khmer adolescent project. I. Epidemiological findings in two generations of Cambodian refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994;182:387–395. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mollica RF, Poole C, Son L, et al. Effects of war trauma on Cambodian refugee adolescents’ functional health and mental health status. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1098–1106. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almqvist K, Brandell-Forsberg M. Refugee children in Sweden: post-traumatic stress disorder in Iranian preschool children exposed to organized violence. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:351–366. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tousignant M, Habimana E, Biron C, et al. The Quebec Adolescent Refugee Project: psychopathology and family variables in a sample from 35 nations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1426–1432. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199911000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geltman PL, Augustyn M, Barnett ED, et al. War trauma experience and behavioral screening of Bosnian refugee children resettled in Massachusetts. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21:255–261. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200008000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sveaass N, Reichelt S. Refugee families in therapy: from referrals to therapeutic conversations. Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;23:119–135. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watters C. Emerging paradigms in the mental health care of refugees. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1709–1718. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellis BH, McDonald H, Lincoln A, et al. Mental health of Somali adolescent refugees: the role of trauma, stress, and perceived discrimination. J Consult Clin Psychol. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.184. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadopoulos R. Working with Bosnian medical evacuees and their families: therapeutic dilemmas. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;4:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellis BH, Rubin A, Betancourt TS, et al. Mental health interventions for children affected by war or terrorism. In: Feerick M, Silverman G, editors. Children exposed to violence. Chapter 7. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkelhor D, Berliner L. Research on the treatment of sexually abused children: a review and recommendations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1408–1423. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKay M, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Addressing the barriers to mental health services for inner-city children and their caretakers. Community Ment Health J. 1996;32(4):353–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02249453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKay M, Nudelman R, McCadam K. Involving inner-city families in mental health services: first interview engagement skills. Res Social Work Pract. 1996;6:462–472. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKay M, Stoewe J, McCadam K, et al. Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their care givers. Health Soc Work. 1998;23:9–15. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKay MM, Hibbert R, Hoagwood K, et al. Integrating evidence-based engagement strategies into “real-world” child mental health settings. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2004;4:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellis BH. Somali adolescents and pathways to mental health care: understanding help seeking within one refugee community. Presented at the 23rd Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; November 15–17, 2007; Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feldman R. Primary health care for refugees and asylum seekers: a review of the literature and a framework for services. Public Health. 2006;120:809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basoglu M. Behavioural and cognitive treatment of survivors of torture. In: Jaranson JM, Popkin MK, editors. Caring for victims of torture. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1998. pp. 131–48. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore LJ, Boehnlein JK. Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression and somatic symptoms in U.S. Mien patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:728–733. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris P, Silove D, Manicavasagar V, et al. Variations in therapeutic interventions for Cambodian and Chilean refugee survivors of torture and trauma: a pilot study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1993;27:429–435. doi: 10.3109/00048679309075799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aroche J, Coello M. Towards a systematic approach for the treatment rehabilitation of torture and trauma survivors in exile: the experience of STARTTS in Australia. Presented at the 4th International Conference of Centres, Institutions and Individuals Concerned with Victims of Organized Violence: “Caring for and Empowering Victims of Human Rights Violations”, DAP; Tagaytay City, Philippines. December 5–9, 1994; [Accessed November, 2007]. Available at: http://www.startts.org.au. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papadopoulos RK. Refugee families: issues of systemic supervision. Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;23:405–422. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arrendondo P, Orjuela E, Moore L. Family therapy with Central American war refugee families. Journal of Strategic and Systemic Therapies. 1989;8:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bemak F. Cross-cultural family therapy with Southeast Asian refugees. Journal of Strategic and Systemic Therapies. 1989;8:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehraby N. Therapy with refugee children. [Accessed November, 2007]; Available at: http://www.swsahs.nsw.gov.au/areaser/Startts/article_2.htm.

- 48.Silove D, Manicavasagar V, Beltran R, et al. Satisfaction of Vietnamese patients and their families with refugee and mainstream mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1064–1069. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.8.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodcock J. Healing ritualswith families in exile. Journal of Family Therapy. 1995;17:397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Layne CM, Pynoos RS, Saltzman WS, et al. Trauma/grief focused group psychotherapy: school based post-war intervention with traumatized Bosnian adolescents. Group Dynamics. 2001;5:277–290. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goenjian AK, Karayan I, Pynoos RS, et al. Outcome of psychotherapy among early adolescents after trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:536–542. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goenjian AK, Walling D, Steinberg AM, et al. A prospective study of posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among treated and untreated adolescents 5 years after a catastrophic disaster. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2302–2308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith P, Dyregrov A, Yule W, et al. Children and war: teaching recovery techniques. Bergen (Norway): Foundation for Children and War; 2000. [Accessed May 15, 2007]. Available at: http://www.childrenandwar.org. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ehntholt KA, Smith PA, Yule W. School-based cognitive-behavioural therapy group intervention for refugee children who have experienced war-related trauma. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;10:235–250. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Onyut LP, Neuner F, Schauer E, et al. Narrative exposure therapy as a treatment for child war survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: two case reports and a pilot study in an African settlement. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schauer E, Neuner F, Elbert T, et al. Narrative exposure therapy in children: a case study. Intervention. 2004;2:18–32. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruf M, Schauer M, Neuner F, et al. KIDNETda highly effective treatment approach for traumatized refugee children. Paper presented at the European Conference on Traumatic Stress (ECOTS). Opatja; June 5–9, 2007; Croatia. [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:4S–26S. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199810001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, et al. A multisite randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.March JS, Amaya-Jackson L, Murray MC, et al. Acognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder after a single-incident stressor. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:585–593. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199806000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saigh PA. The use of an in vitro flooding package in the treatment of traumatized adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1989;19:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen JA, Berliner L, March JS. Treatment of children and adolescents. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 106–138.pp. 330–332. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chorpita BF. Toward large-scale implementation of empirically supported treatments for children: a review and observations by the Hawaii Empirical Basis to Services Task Force. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:165–190. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saunders BE, Berliner L, Hanson RF, editors. Child Physical and Sexual Abuse: Guidelines for Treatment (Final Report: January 15, 2003) Charleston. SC: National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deblinger E, Lippmann J, Steer R. Sexually abused children suffering posttraumatic stress symptoms: initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreat. 1996;1:310–321. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deblinger E, Steer RA, Lippman J. Two-year follow-up study of cognitive-behavioral therapy for sexually abused children suffering posttraumatic stress symptoms. Child Abuse Negl. 1999;23:1371–1378. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: initial findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:42–50. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Interventions for sexually abused children: initial treatment findings. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: outcome during one-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(9):1228–1235. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Knudson K. Treating sexually abused children: 1 year follow up of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.King NJ, Tonge BJ, Mullen P. Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: a randomizedclinical trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1347–1355. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith P, Yule W, Perrin S, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for PTSD in children and adolescents: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1051–1061. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318067e288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Najavits LM. Seeking safety: a treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Najavits LM, Gallop RJ, Weiss RD. Seeking safety therapy for adolescent girls with PTSD and substance use disorder: a randomized controlled trial. [Accessed October, 2007];J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006 33:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9034-2. Available at: www.seekingsafety.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jaycox LH. Cognitive-behavioral intervention for trauma in schools. Longmont (CO): Sopris West Educational Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):311–318. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, et al. A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(5):603–611. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Amaya-Jackson L, Reynolds V, Murray MC, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: protocol and application in school and community settings. Cogn Behav Pract. 2003;10(3):204–213. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saltzman WR, Pynoos RS, Layne CM, et al. Trauma- and grief-focused intervention for adolescents exposed to community violence: results of a school-based screening and group treatment protocol. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice. 2001;5:291–303. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Macy RD. Community-based trauma response for youth. New Dir Youth Dev. 2003;98:29–49. doi: 10.1002/yd.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khamis V, Macy R, Coignez V. Impact of the classroom/community/camp-based intervention program on Palestinian children: US Agency for International Development and SAVE report on Palestinian children. 2004 Available at: http://www.usaid.gov/wbg/reports/Save2004_ENG.pdf.

- 82.Saxe GN, Ellis H, Fogler J, et al. Comprehensive care for traumatized children: an open trial examines treatment using trauma system therapy. Psychiatr Ann. 2005;53:443–448. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guildford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Knudsen K. Treating childhood traumatic grief: a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1225–1233. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000135620.15522.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Staron VR. A pilot study of modified cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood traumatic grief (CBT-CTG) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1465–1473. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000237705.43260.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Rank E, et al. Traumatic grief: a case of loss-induced trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(7):1003–1009. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC. Consensus criteria for traumatic grief: a preliminary empirical test. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:67–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hoagwood KE, Burns BJ, Kiser L, et al. Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(9):1179–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chorpita BF. Treatment manuals for the real world: where do we build them? Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2002;9:431–433. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Final report on the Child and Adolescent Trauma Treatment Consortium (CATS) project for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2006 Oct; Available at: www.samhsa.gov.

- 91.de Arellano MA, Danielson CK. Culturally-modified trauma-focused therapy for treatment of Hispanic child trauma victims. Presented at the Annual San Diego Conference on Child and Family Maltreatment; January 22–26, 2006; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Center for Multicultural Human Services. [Accessed November, 2007];Member of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Available at: www.nctsn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wolpe J. Basic principles and practices of behavior therapy of neuroses. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;125(9):1242–1247. doi: 10.1176/ajp.125.9.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Oxford (UK): International Universities Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs DS, et al. Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:715–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Keane TM, Fairbanks JA, Caddell JM, et al. Implosive (flooding) therapy reduces symptoms of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans. Behav Ther. 1989;20:245–260. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kazdin AE, Weisz JR. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weisz JR, Hawley KM, Doss A. Empirically tested psychotherapies for youth internalizing and externalizing problems and disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2004;13(4):729–815. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.05.006. Special issue: Evidence-Based Practice, Part I: Research Update. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kazdin AE, Weisz JR. Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:19–36. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ollendick TH, King NJ. Empirically supported treatments for children and adolescents. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescent therapy: cognitived-behavioral procedures. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 386–425. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Herman JL. Trauma and recovery from domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stepakoff S, Hubbard J, Katoh M, et al. Trauma healing in refugee camps in Guinea: a psychosocial program for Liberian and Sierra Leonean survivors of torture and war. Am Psychol. 2006;61:921–932. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Seligman MEP, Reivich K, Jaycox L, et al. The optimistic child. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Keane TM, Marshall AD, Taft CT. Posttraumatic stress disorder: etiology, epidemiology, and treatment outcome. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:161–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stubenbort KJ, Donnelly GR, Cohen J. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for bereaved adults and children following an air disaster. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice. 2001;5:261–276. [Google Scholar]