Abstract

Purpose of Review.

Mental health apps are intriguing yet challenging tools for addressing barriers to treatment in primary care. In the current review, we seek to assist primary care professionals with evaluating and integrating mental health apps into practice. We briefly summarize two leading frameworks for evaluating mental health apps and conduct a systematic review of mental health apps across a variety of areas commonly encountered in primary care.

Recent Findings.

Existing frameworks can guide professionals and patients through the process of identifying apps and evaluating dimensions such as privacy and security, credibility, and user experience. For specific apps, several problem areas appear to have relatively more scientific evaluation in the current app landscape, including PTSD, smoking, and alcohol use. Other areas such as eating disorders not only lack evaluation, but contain a significant subset of apps providing potentially harmful advice.

Summary

Overall, individuals seeking mental health apps will likely encounter strengths such as symptom tracking and psychoeducational components, while encountering common weaknesses such as insufficient privacy settings and little integration of empirically-supported techniques. While mental health apps may have more promise than ever, significant barriers to finding functional, usable, effective apps remain for health professionals and patients alike.

Keywords: apps, smartphone, mobile, mental, primary care, technology

Introduction

American consumers spend from 2–5 hours a day using their smartphones (1). Given the emerging significance of smartphones in everyday American life, optimizing smartphone applications (apps) for use in monitoring and intervening upon chronic health conditions has become a burgeoning area of commerce and research. For health professionals in outpatient primary care, psychiatric conditions are common presenting problems, with mental health concerns estimated to be the primary diagnosis for around 60 million outpatient visits to physician’s offices in 2015 alone (2).

Despite frequent experiences with patients’ mental health concerns in outpatient care, many primary care professionals feel ill-prepared to provide treatment (3). Providers’ discomfort is unfortunate given that many patients prefer to receive mental health treatment in primary care settings (4). Mental health apps provide a compelling tool for addressing barriers to mental health treatment, including provider discomfort and lack of time. Apps afford an alternative channel for engaging patients and can provide symptom monitoring, tailored, evidence-based treatment that is integrated into patients’ everyday lives, and other clinical functions. See Table 1 for a more extensive list of common intended purposes of mental health apps. Primary care professionals and patients appear to be amenable to integrating apps into care. Most primary care physicians currently use smartphones or tablets, and rate smart devices as important or very important to their daily work (5). In particular, medical students and junior professionals report relying upon apps as important sources of educational and reference information (5). On the patient side, use of mental health apps is high and growing; in one study, 69% of respondents and 80% under age 45 reported a desire to use apps for mental health monitoring (6). While smartphone access lessens with lower socioeconomic status (7), primary care patients across the socioeconomic spectrum report significant interest in using health-related apps (8).

Table 1.

Common Intended Purposes of Mental Health Apps

| Purpose |

|---|

| Assessment and diagnosis |

| Symptom monitoring |

| Intervention |

| Reminders and prompts |

| Patient and provider educatio |

| Social support |

| Assistance with locating mental health resources |

Note. This list is not comprehensive. Each individual app’s effectiveness in achieving an intended purpose must be evaluated by providers and patients within the particular treatment context.

Despite the promise of mental health apps, navigating the multitude of those targeting mental health can be daunting. Hundreds or even thousands of mental health apps exist commercially for different conditions. Clinicians and consumers are often uncertain whether a mental health app is effective, usable, protective of patient health data, free, or would involve barriers to typical practice. Further, apps are constantly appearing, disappearing, and being updated in the marketplace.

Given the aforementioned challenges, in the current review, we attempt to assist primary care health professionals with processes for evaluating and integrating mental health apps into practice. To do so, we cover three areas: 1) we summarize two leading frameworks for evaluating mental health apps; 2) we conduct a systematic review of the typical characteristics and evidence base for mental health apps across a variety of mental health areas commonly encountered in primary care; and, 3) we generate recommendations for clinicians based upon current frameworks, evidence, and their application to primary care.

Frameworks for Evaluating Mental Health Apps

To address the swift changes in the marketplace and wide configuration of factors that must be evaluated within mental health apps, several leading frameworks have emerged for evaluating apps for professional use. We will illustrate two leading examples, although these and other frameworks will continue to evolve. The American Psychiatric Association App Evaluation Model provides a rubric and corresponding course for professional evaluation of apps, whereas PsyberGuide provides a rubric and specific ratings of apps for use by professionals and patients.

American Psychiatric Association App Evaluation Model.

First, while the American Psychiatric Association (APA) offers no firm list of endorsed mental health apps, it provides an evaluation method and corresponding online course for use in evaluating mental health apps (9). Designed for physicians and other health professionals, the evaluation method teaches users to filter the thousands of available mental health apps through a rubric to winnow down available apps and systematically evaluate apps according to several key dimensions. Initially, professionals are coached to gather information about apps’ background (i.e., price, last update, developer) to determine whether they should proceed with considering the app. Next, professionals examine an app’s safety, considering aspects such as the privacy and security of data shared through the app. Subsequently, efficacy and usability are evaluated with methods taught to determine the evidence supporting the app presented, and the ease with which one can use and adhere to the purported benefits of the app. Lastly, professionals determine the “interoperability” of the remaining apps; in other words, how the app may allow data sharing among the health professional, patient, and others in useful ways. By functioning as a filtering framework for evaluating apps, the APA App Evaluation Model is a useful tool for yielding a collection of apps for use in primary care.

Second, PsyberGuide – a non-profit website – rates mental health apps based on credibility, transparency, and user experience (10). PsyberGuide is a collaborative endeavor among an academic management team, a scientific board of directors, and a non-profit organization. While PsyberGuide also does not endorse particular apps, it provides detailed information about specific apps for health professionals and patients to review and determine whether specific products may address their needs. The site currently categorizes available apps into four mental health areas – Stress and Anxiety, Mood Disorders, Schizophrenia, and PTSD – and provides clear rubrics for informing visitors about not only specific ratings, but the process underlying these ratings. For some apps, supplemental expert reviews from selected professionals are available. The site is regularly updated with new apps, fresh data, and evolving evaluations of changes made to previously-reviewed apps.

Together, these two frameworks are valuable guides for health professionals and patients who intend to identify specific apps for use. In the next section, we provide a snapshot assessing the current mental health app landscape across major mental health problem areas. This snapshot is intended to offer providers and patients a broad context within which to base their search and evaluation process using frameworks like the two reviewed above.

Existing Characteristics of Mental Health Apps For Primary Care

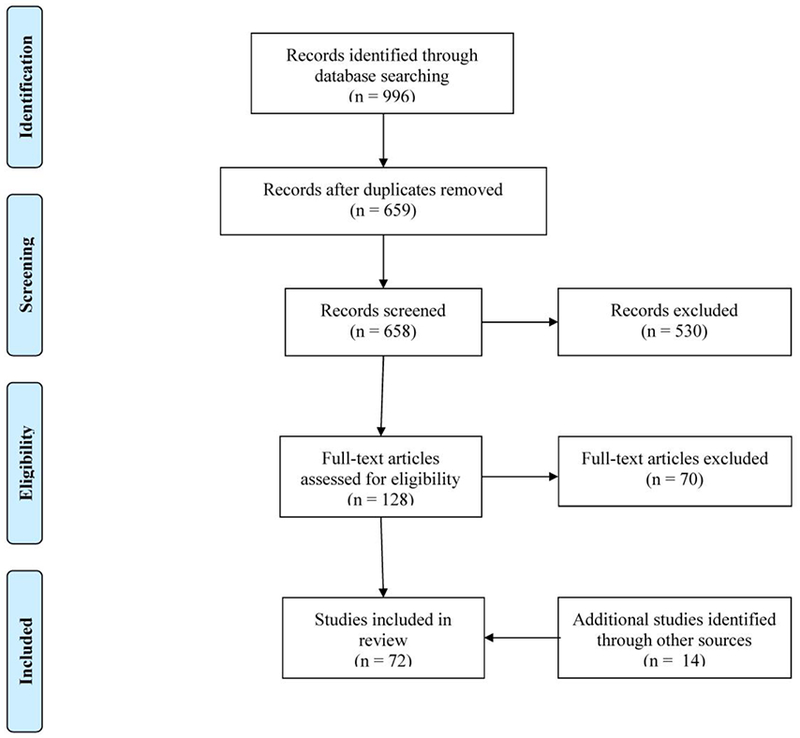

To conduct a systematic review of the typical characteristics and evidence base for mental health apps across mental health areas commonly encountered in primary care, we initially restricted our literature search to mental health apps studied in primary care. However, there were nearly no RCTs, pilot examinations, or reviews of mental health apps that were specific to primary care settings. As a result, we instead searched for reviews evaluating mental health apps across treatment settings. To do so, we conducted a series of searches using the keywords and procedures found in Table 2, resulting 996 results. Following the process outlined in Figure 1, we next removed duplicates, screened records, and then conducted a detailed full-text examination of the remaining records. To meet inclusion criteria, reviews were required to systematically review and summarize evidence for apps across multiple studies. In addition, reviews were required to include apps available on smartphones, designed for patient use, and that functioned in assessment, identification, screening, or treatment roles for mental health conditions (defined as either DSM-5 disorders or mental health constructs and treatment techniques pertaining to DSM-5 disorders). Finally, articles reviewing broader issues of ethics, economics, and the methodologies for reviewing or developing apps were excluded. Both evaluators (JM, SA) reviewed and rated each full-text record, and all discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached. This process yielded 58 eligible reviews, with an additional 14 eligible results stemming from references contained within the main results or our previous knowledge.

Table 2.

Listing of Search Terms Used In PsychInfo and PubMed Searches

| Database | Combinations of Search Terms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PsycInfo | App OR apps OR application OR applications | Phone OR mobile OR smartphone OR cellphone OR iphone OR android | AND Review | Mental health or mental illness or mental disorder or psychiatric illness |

| PsycInfo | App OR apps OR application OR applications | Phone OR mobile OR smartphone OR cellphone OR iphone OR android | AND Review | Alcohol OR suicide OR suicidal ideation OR self harm OR autism OR schizophrenia OR smoking OR mindfulness OR stress OR pain OR youth OR adolescent OR anxiety OR late life OR addiction OR elderly |

| PubMed | App OR apps OR application OR applications | Phone OR mobile OR smartphone OR cellphone OR iphone OR android | AND Review TYPE: Review | Mental health or mental illness or mental disorder or psychiatric illness |

| PubMed | App OR apps OR application OR applications | Phone OR mobile OR smartphone OR cellphone OR iphone OR android | AND Review | Alcohol OR suicide OR suicidal ideation OR self harm OR smoking OR stress OR youth OR adolescent OR anxiety OR addiction |

| PubMed | Smartphone OR mobile phone | Apps OR applications | TYPE: Review | AND systematic |

Note. Each row in the Database column refers to a separate search instance. Searches were completed on 3/11/18 (PsycInfo) and 3/12/2018 (PubMed).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating articles included in the review.

Existing Reviews Evaluating Mental Health Apps

Overall, the eligible systematic reviews varied in their methodologies (e.g., meta-analysis versus narrative review), search strategies, restriction to iPhone versus Android apps, and other dimensions. We attempt to summarize their findings at a general level for each mental health problem area while referring readers to specific reviews for additional details and examples of apps. While we seek to characterize the themes present across reviews for each problem area, not every review is summarized or cited in the text due to space. Table 3 provides a full list of all eligible reviews, organized by problem area.

Table 3.

Articles Included in the Review by Problem Area

| Problem Area | Reference | Problem Area | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Use Disorders | Berman et al. (2016) (47) | Suicide Prevention and Self-Harm | Aguirre et al. (2013) (26) |

| Choo & Burton (2018) (42) | de la Torre et al. (2017) (28) | ||

| Cohn etal. (2011) (39) | Larsen et al. (2016) (25) | ||

| Fowler et al. (2016) (46) | Luxton et al. (2015) (27) | ||

| Giroux et al. (2017) (77) | Pospos et al. (2017) (78) | ||

| Hoeppner et al. (2017) (38) | Witt etal. (2017) (29) | ||

| Kazemi et al. (2017) (45) | |||

| Meredith et al. (2015) (49) | Eating Disorders | Fairborn & Rothwell (2015) (24) | |

| Milward et al (2016) (44) | Juarascio et al. (2015) (23) | ||

| O’Rourke et al. (2016) (48) | |||

| Quanbeck et al. (2014) (43) | General/Other | Bakker et al. (2016) (79) | |

| Savic et al. (2013) (40) | Bateman et al. (2017) (80) | ||

| Weaver et al. (2013) (41) | Christensen et al. (2013) (81) | ||

| Donker et al. (2013) (82) | |||

| Anxiety and PTSD | Alyami et al. (2017) (15) | Lui etal. (2017) (83) | |

| Bry et al. (2017) (72) | Menon et al. (2017) (84) | ||

| Firth etal. (2017) (13) | Rathbone et al. (2017a) (85) | ||

| Rodriguez-Paras et al. (2017) (18) | Runyan et al. (2015) (86) | ||

| Sucala et al. (2017) (12) | |||

| Van Ameringen et al. (2017) (14) | Lifespan | Bry etal. (2017) (72) | |

| Van Singer et al. (2015) (16) | Dubad et al. (2018) (71) | ||

| Grist et al. (2017) (69) | |||

| Bipolar Disorder | Dogan etal. (2017) (87) | Hollis etal. (2017) (88) | |

| Gliddon et al. (2017) (31) | Moussa et al. (2017) (70) | ||

| Meyer etal. (2018) (89) | O’Rourke et al. (2016) (48) | ||

| Nicholas et al. (2017) (34) | Seko et al. (2014) (73) | ||

| Nicholas et al. (2015) (30) | |||

| Van Ameringen et al. (2017) (14) | Mindfulness and Cognitive-Behavioral | Mani et al. (2015) (74) | |

| Rathbone et al. (2017b) (75) | |||

| Depression | Callan et al. (2017) (21) | Sucala et al. (2013) (90) | |

| Dogan et al. (2017) (87) | |||

| Huguet et al. (2016) (20) | Nicotine Use Disorder | Abroms et al. (2013) (57) | |

| Meyer et al. (2018) (89) | Abroms et al. (2011) (58) | ||

| Pospos et al. (2017) (78) | Bennett et al. (2015) (50) | ||

| Shen et al. (2015) (22) | Ferron et al. (2017) (59) | ||

| Van Ameringen et al. (2017) (14) | Ghorai et al. (2014) (91) | ||

| Haskins et al. (2017) (54) | |||

| Schizophrenia | Bell et al. (2017) (37) | Heminger et al. (2016) (60) | |

| Firth & Torous (2015) (36) | Regmi et al. (2017) (51) | ||

| Meyer et al. (2018) (89) | Thornton et al. (2017) (53) | ||

| Whittaker et al. (2016) (52) | |||

| Stress | Coulon et al. (2016) (61) | ||

| Lyzwinski et al. (2018) (92) | Pain | Bhattarai et al. (2018) (67) | |

| de la Vega et al. (2014) (66) | |||

| Lalloo et al. (2015) (65) | |||

| Machado et al. (2016) (68) | |||

| Portelli & Eldred (2016) (64) | |||

| Wallace & Dhingra (2014) (63) |

Note. Some articles are listed under more than one category due to those articles reviewing apps in multiple problem areas.

Anxiety and PTSD.

While anxiety is one of the most common mental health issues encountered in primary care (11), there are currently few apps available for anxiety or PTSD that are well-regarded across evaluation criteria. Apps that provide anxiety intervention are difficult to find; one examination of thousands of commercial anxiety apps yielded only 52 functional apps that went beyond text or audio information to offering psychological techniques to reduce anxiety (12). Among apps that have been tested with feasibility or efficacy data, app interventions do appear to reduce anxiety relative to control conditions when delivered as part of broader interventions (12,13). However, studies evaluating apps for specific disorders such as social anxiety disorder and panic disorder have resulted in unclear empirical support or methodological issues that prevent conclusions (14,15). For panic disorder, commercially-available apps have low quality and self-help value (16), with no single app meeting all assessed criteria such as the source of the apps’ content and transparency.

For PTSD, there have been more promising findings, including data supporting the use of an app-based PTSD Checklist-Civilian for assessment (17). Additionally, the PTSD Coach intervention, which was developed by the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA), has been evaluated repeatedly with promising although not completely supportive results (14). In addition, the VA developed another app, PE Coach, to provide prolonged exposure therapy, with efficacy evaluations upcoming (14). For the remainder of commercial apps that have not been rigorously evaluated, their scientific grounding, usability, and efficacy of their techniques for addressing anxiety and PTSD in a clinically significant way is uncertain (18).

Depression.

To assist in the identification and management of depression, there are data supporting the use of an app-based version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for assessment (14,19), and the use of several monitoring apps for tracking depressive symptoms (14). For treatment, there is no strong scientific evidence supporting publicly available apps, with high variability in apps’ usability and a frequent lack of safety and privacy information (20,21). In addition to infrequent descriptions of the source of app content (22), evidence-based principles seem to be present in only about 10% of scientific and marketplace apps (20). Van Ameringen and colleagues (14) provide a brief overview of depression apps that are exceptions and have been evaluated scientifically.

Eating Disorders.

Apps may be uniquely suited to treat eating disorders, addressing patients’ common fears of stigmatization and ambivalence to change. A review of consumer eating disorder intervention apps, however, suggests that apps have significant room for improvement (23). Weaknesses of current apps include reliance on empirically unsupported treatments (23) and frequent provision of variable, poor, or even harmful advice (24). Current apps also fail to take advantage of smartphone capabilities, relying solely on manual data entry instead of automated input (e.g. geolocation, time), artificial intelligence, and ecological momentary assessment/intervention (23,24). Future apps may integrate these potentially valuable technological features to enhance treatment.

Suicide Prevention and Self-Harm.

Larsen and colleagues (25) provide an excellent overview of existing app features, finding that half of identified apps followed evidence-based strategies, all apps possessed some elements of best practice guidelines, and only a few apps contained potentially harmful elements. At the same time, few apps revealed the source of their content or had interactive content (25,26). Like with eating disorders, suicide prevention apps have excellent potential for building upon smartphone technological capabilities, and examples such as the Relieflink and MY3 apps illustrate exciting features such as assistance in locating nearby suicide resource centers, emergency buttons, and in-app social support networks (27). While many suicide prevention apps may contain evidence-based strategies, few have been scientifically evaluated, with various reviews finding between two and six original scholarly evaluations of apps (28,29).

Bipolar Disorder.

Nicholas and colleagues (30) examined apps for bipolar disorder that were publicly available in Australia, although these nearly universally corresponded to apps in the United States and Britain. None had been subject to research evaluation, converging with later work finding only two potentially effective evidence-based mobile interventions for bipolar disorder (31): PRISM, which has RCT support (32), and IABD, which has undergone a pilot study (33). Of the other informational and self-management apps available, only one third cited their sources of information and even smaller percentages adhered to best practice guidelines or used validated screening measures (30). In an examination of user preferences, the greatest strengths of bipolar symptom-tracking apps were their facilitation of mood-tracking (34). Some users reported not only sharing their insights gained with healthcare providers, but also desiring to export raw data from the app to show their healthcare providers. Aligning with this desire, the most cited weaknesses of apps for bipolar were insufficient technological capacities, along with privacy issues and technical failures (34).

Schizophrenia.

Although schizophrenic symptoms like disorganization and cognitive impairment may hinder a patient’s capacity to use technology, over two thirds of first-episode psychosis patients own internet-enabled cell phones (35). A systematic review found five independent studies testing smartphone apps for schizophrenia, covering symptom monitoring, mental health self-management, and physical activity promotion (36). The combined results demonstrated low dropout, high levels of self-initiated app usage, and high perceived helpfulness of the apps by patients. Comparing app symptom monitoring to a text message-based monitoring in one trial, participants completed a greater number of entries and preferred to use the smartphone app compared to the texting interface. Furthermore, there were no reports of app usage increasing paranoia or exacerbating symptoms. These results converge with other reviews (37) to suggest that despite concerns about the capacity of patients with schizophrenia and psychotic disorders to use mental health apps, these patients are capable, engaged with smartphones, and may benefit from careful implementation.

Alcohol Use Disorders.

There seems to be great changeover in alcohol use disorder apps, with one review finding that over 35% of apps reviewed were no longer available by the conclusion of their study (38). Apps available in the marketplace are generally geared toward calculating blood alcohol content (38), providing information, monitoring use, and assisting with general support and motivation (39,40). Unfortunately, many available apps may encourage alcohol consumption, either directly or through motivating drinking by virtue of users’ desire to check their blood alcohol content (41). Currently, the monitoring functions of alcohol use disorder apps may be the most helpful feature as an adjunct for health professionals who are delivering evidence-based treatment (42), as few apps were designed with evidence-based treatment guidelines in mind (38), and little scientific evidence supports their use (39,43). In addition to monitoring features, users may also appreciate the provision of drinking-related information and feedback (44). In terms of current evidence, there are differing interpretations. Several researchers have found that while there is initial positive evidence for apps resulting in reduced alcohol use, further evidence is needed for this modality (45–48). However, other reviews have concluded that not only is further evidence needed, but that the existing RCTs largely show a lack of significant reductions in alcohol use (42,49).

Nicotine Use Disorder.

Most available apps provide advice for limiting the number of cigarettes smoked or calculating benefits to reducing smoking, but do not provide other strategies such as tracking cigarette use (50). However, unlike several areas we have reviewed, there is some support from pilot RCTs that apps increase the quit rate of users, although there is uncertain support for relapse prevention (51) and other reviews have found no intervention studies meeting stringent eligibility criteria (52). Finding functional and effective apps is a tremendous challenge with nicotine use, as only 7% of seemingly relevant apps may target smoking cessation and be applicable to individuals attempting to quit (50). The average available app also tends to have poor to acceptable quality (53). There seems to be a divide between Android and iPhone apps, such that few apps are available across both platforms (50), and only about half of scientifically-evaluated apps remain available in the marketplace; these apps are summarized by Haskins and colleagues (54). Among the remainder of commercially available apps, adherence to best practices such as the U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence (55) or tailoring interactively to users’ needs tends to be low (56–58). Given the importance of tailoring, several reviews have evaluated smoking cessation apps for specific smoking subpopulations such as people with psychosis (59) or pregnant women (60).

Stress.

Stress may be a domain with promise, as there is high adherence to evidence-based strategies, high usability, and approximately half of reviewed apps seem to be sufficiently transparent in terms of describing the source of content, confidentiality, privacy, and other information (61). In total, Coulon and colleagues (61) identified at least 32 apps that were evidence-based and had acceptable functionality, often focusing on approaches such as mindfulness, meditation, and diaphragmatic breathing. Further, approximately 95% of patients in one study reported using apps to access evidence-based strategies for stress would be helpful, increasing the potential impact of stress management apps (62).

Pain.

For pain, reviews of existing apps have consistently found them to be developed by software developers or lay people, with little input from healthcare professionals (63–65), although many may contain recommendations by health professionals and associations (66). Perhaps as a consequence, there is little reference in apps to evidence-based guidelines or strategies (67), with only 6 out of 195 marketplace apps in one review containing identifiable theoretical content (64). Another review found that only 1 out of 279 apps described any scientific evaluation, and no large scale RCTs had been conducted with any apps (65). Slight differences were reported in a review of apps for lower back pain, as most apps contained some elements of interventions recommended by the 2016 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for evidence-based interventions (68). However, usability was low, and no app had been scientifically evaluated for its effectiveness in reducing lower back pain (68).

Mental Health Across the Lifespan.

Few apps have been specifically developed for children and adolescents or for older adults, and the benefit of mental health mobile apps for these populations is unclear (69,70). Among adolescents, the greatest concerns about app use include privacy and discretion, with healthcare providers echoing these concerns as being crucial when considering adolescent populations (69). While youth are generally receptive to apps, perceptions of app usability varies and may be lower among adolescents with mental health disorders compared to those without, requiring greater attention to matching adolescents in treatment with appropriate apps (71). Youth-oriented mental health apps target a broad range of subjects, from general well-being to depression, OCD, eating disorders, anxiety, and suicide prevention (69). Two reviews demonstrate a distinction between two app “pools”: an empirically-driven selection of child mental health apps drawn from publications (69) and a selection of downloadable consumer anxiety apps (72). One notable difference is that while the consumer pool contains more apps with active treatment components (50%) than the empirically-driven pool (7%), the majority of apps from the consumer pool do not use evidence-based treatment components (72). This distinction dovetails with a review of scientifically evaluated apps finding that all apps were monitoring or assessment ones, rather than involving psychological intervention techniques (73).

For older adults, studies of apps have been largely geared toward older adults with dementia and mild cognitive impairment (70). In the few studies reviewed, older adults did not demonstrate substantial difficulty using apps and other mobile technologies after receiving coaching tutorials. Generally, apps and mobile technologies have been examined only as assessment aids among older adults, showing promise while not being tested in randomized designs or using intervention formats (70).

Mindfulness and Cognitive-Behavioral Apps.

Mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral approaches are relevant across a variety of mental health and well-being areas, and there are hundreds of purported “mindfulness” smartphone apps available on commercial platforms (74,75). Unfortunately, only about 4% of mindfulness apps include both mindfulness training and education components (74), making relevant apps challenging to locate for professionals and patients. Apps that included both components frequently incorporate guided meditation, timers, and reminders to facilitate mindfulness practice. They also possess acceptable quality in terms of engagement, functionality, visual aesthetics, and information soundness (74). Despite these features, however, there is a lack of scientific evidence (74). While cognitive-behavioral apps are less common than mindfulness ones commercially, their short-term effectiveness appears to be supported in the RCTs that have been conducted (75).

Summary of Current Findings

The current review overviewed two leading frameworks for evaluating mental health apps, and captured a snapshot of current mental health apps’ empirical support and characteristics such as adherence to best practice guidelines, development processes, availability, data security, and usability. Several problem areas emerged as having relatively more scientific evaluation of apps, including PTSD, smoking, and alcohol use. Other areas such as eating disorders not only generally lacked scientific evaluation, but contained a significant subset of apps providing poor or harmful advice. More generally, common strengths of available apps include symptom tracking features, psychoeducational components, and high user engagement, while common weaknesses include insufficient privacy settings and little integration of empirically-supported treatments outside of scientifically-developed apps. While some specific apps demonstrate great promise, ethical and sociocultural issues surrounding the use of such apps warrant consideration.

Clinical Implications.

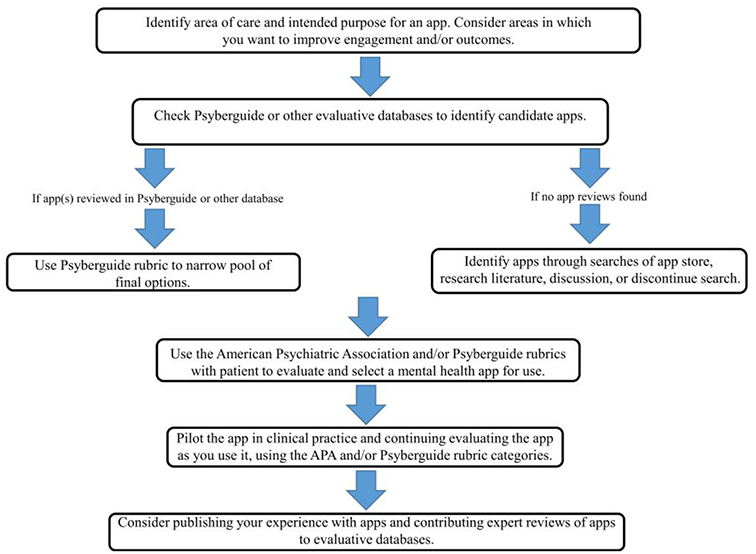

In most problem areas, extensive search processes were necessary to find apps that were relevant, functional, and in preferred language and formats. Prior to evaluating key features of individual apps, these search hurdles present substantial barriers for clinicians and patients. For clinicians, it may be expedient to build up a collection of apps matched to regularly-occurring presenting problems. This collection could be regularly updated using sources like recent review papers of apps in particular problem areas. Additionally, regular collaborative use of apps within a collection could help the clinician to develop typical scripts and language for introducing and discussing the profiles of particular apps with patients. To summarize our recommendations for developing and updating such collections, we outline our proposed approach to using mental health apps in primary care in Figure 2. In addition to integrating the professional evaluation frameworks we reviewed earlier, this approach reminds providers to continue evaluation throughout the use of an app, and asks providers to consider contributing their experiences to the professional knowledge base.

Figure 2.

Proposed model for using mental health apps in primary care.

In addition to the considerations already discussed, clinicians need to weigh potential ethical issues that may arise (76). For instance, implicit in evaluating the privacy and security of apps is the fact that apps may be used to collect and transmit sensitive information. Because the app is not contained within a traditional healthcare environment controlled by the clinician, both clinicians and patients may not consider novel threats to privacy and confidentiality. For instance, apps that are used to assist with treating substance use (76) or problems like sexual dysfunction may reveal information to others that is illegal and/or perceived as embarrassing. Patient need to be able to fully know, evaluate, and consent to the risks inherent in app use. Related to these ethical issues, access to apps is not equivalent across demographic and cultural groups (7). As part of apps’ general lack of an evidence base, there has been little work evaluating the effectiveness and tailoring of apps across sociocultural dimensions. From app cost and smartphone access to intervention content, usability, and privacy, clinicians need to consider sociocultural dimensions as they would with other modes of mental health monitoring and treatment.

Limitations and Conclusion.

This guide relied on systematic reviews across a variety of problem areas, rather than individually examining the thousands of studies covered by these systematic reviews. Health professionals are encouraged to consult the specific systematic reviews listed in Table 3 for more detailed guides to problem areas of interest. Additionally, few evaluations specifically examined primary care settings and the generalizability of apps across settings and populations, so the implementation of apps with individuals should be carefully monitored.

The ubiquity of smartphones and their application to mental health problems provide an interesting and useful starting point for clinicians and patients to engage in new discussions about how to approach many psychiatric and substance use issues. Harnessing the power of technology has significant potential for strengthening the doctor-patient relationship and extending mental health work outside of the traditional clinical setting. In spite of the identified challenges and the difficulties of finding suitable apps, clinicians and patients now have more promising mental health apps at their fingertips than ever before.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest. Joshua Magee reports grant K23DA037320 from National Institutes of Health supporting his work on the study. Sarah Adut declares that she has no conflict of interest. Kevin Brazill declares that he has no conflict of interest. Stephen Warnick declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References and Recommended Reading

Recently published papers of particular interest have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Hacker Noon. How much time do people spend on their mobile phones in 2017?. 2017. https://hackernoon.com/how-much-time-do-people-spend-on-their-mobile-phones-in-2017-e5f90a0b10a6

- 2.Rui P, Okeyode T. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 State and National Summary Tables. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2015_namcs_web_tables.pdf

- 3.Loeb DF, Bayliss EA, Binswanger IA, Candrian C, DeGruy FV. Primary care physician perceptions on caring for complex patients with medical and mental illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2012:27(8):945–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mickus M, Colenda CC, Hogan AJ. Knowledge of mental health benefits and preferences for type of mental health providers among the general public. Psychiatr Serv. 2000:51(2):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaman H, Yavuz E, Er A, Vural R, Albayrak Y, Yardimci A, et al. The use of mobile smart devices and medical apps in the family practice setting. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016:22(2):290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torous J, Friedman R, Keshvan M. Smartphone ownership and interest in mobile applications to monitor symptoms of mental health conditions. J Med Internet Res. 2014:16(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pew Research Center. Mobile fact sheet. 2018. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/

- 8.Ramirez V, Johnson E, Gonzalez C, Ramirez V, Rubino B, Rossetti G. Assessing the use of mobile health technology by patients: An observational study in primary care clinics. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2016:4(2):e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. App Evaluation Model. 2018. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/mental-health-apps/app-evaluation-model

- 10.One Mind Inc. PsyberGuide. 2018. https://psyberguide.org/

- 11.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007:146:317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sucala M, Cuijpers P, Muench F, Cardoş R, Soflau R, Dobrean A, et al. Anxiety: There is an app for that. A systematic review of anxiety apps. Depress Anxiety. 2017:34(6):518–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firth J, Torous J, Nicholas J, Carney R, Rosenbaum S, Sarris J. Can smartphone mental health interventions reduce symptoms of anxiety? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2017:218(January):15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.•.Van Ameringen M, Turna J, Khalesi Z, Pullia K, Patterson B. There is an app for that! The current state of mobile applications (apps) for DSM-5 obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and mood disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2017:34(6):526–39.Comprehensive review of apps across anxiety, OCD, PTSD, and mood disorders.

- 15.Alyami M, Giri B, Alyami H, Sundram F. Social anxiety apps: A systematic review and assessment of app descriptors across mobile store platforms. Evid Based Ment Health. 2017:20(3):65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Singer M, Chatton A, Khazaal Y. Quality of smartphone apps related to panic disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2015:6:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bush NE, Skopp N, Smolenski D, Crumpton R, Fairall J. Behavioral screening measures delivered with a smartphone app: Psychometric properties and user preference. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013:201(11):991–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Paras C, Tippey K, Brown E, Sasangohar F, Creech S, Kum H-C, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and mobile health: App investigation and scoping literature review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017:5(10):e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fann JR, Berry DL, Wolpin S, Austin-Seymour M, Bush N, Halpenny B, et al. Depression screening using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 administered on a touch screen computer. Psychooncology. 2009:18(1):14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huguet A, Rao S, McGrath PJ, Wozney L, Wheaton M, Conrod J, et al. A systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral activation apps for depression. PLoS One. 2016:11(5):e0154248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callan JA, Wright J, Siegle GJ, Howland RH, Kepler BB. Use of computer and mobile technologies in the treatment of depression. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017:31(3):311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen N, Levitan M-J, Johnson A, Bender JL, Hamilton-Page M, Jadad A (Alex) R, et al. Finding a depression app: A review and content analysis of the depression app marketplace. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015:3(1):e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juarascio AS, Manasse SM, Goldstein SP, Forman EM, Butryn ML. Review of smartphone applications for the treatment of eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015:23(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairburn CG, Rothwell ER. Apps and eating disorders: A systematic clinical appraisal. Int J Eat Disord. 2015:48(7):1038–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen ME, Nicholas J, Christensen H. A systematic assessment of smartphone tools for suicide prevention. PLoS One. 2016:11(4):e0152285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguirre RTP, McCoy MK, Roan M. Development guidelines from a study of suicide prevention mobile applications (apps). J Technol Hum Serv. 2013:31(3):269–93. [Google Scholar]

- 27.•.Luxton DD, June JD, Chalker SA. Mobile health technologies for suicide prevention: Feature review and recommendations for use in clinical care. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2015:2(4):349–62.Clinically-oriented review of mobile health in suicide prevention, emphasis on future technological capabilities.

- 28.de la Torre I, Castillo G, Arambarri J, López-Coronado M, Franco MA. Mobile apps for suicide prevention: Review of virtual stores and literature. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017:5(10):e130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witt K, Spittal MJ, Carter G, Pirkis J, Hetrick S, Currier D, et al. Effectiveness of online and mobile telephone applications (‘apps’) for the self-management of suicidal ideation and self-harm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017:17(1):297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholas J, Larsen ME, Proudfoot J, Christensen H. Mobile apps for bipolar disorder: A systematic review of features and content quality. J Med Internet Res. 2015:17(8):e198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gliddon E, Barnes SJ, Murray G, Michalak EE. Online and mobile technologies for self-management in bipolar disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2017:40(3):309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depp CA, Ceglowski J, Wang VC, Yaghouti F, Mausbach BT, Thompson WK, et al. Augmenting psychoeducation with a mobile intervention for bipolar disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2015:174:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wenze SJ, Armey MF, Miller IW. Feasibility and acceptability of a mobile intervention to improve treatment adherence in bipolar disorder: A pilot study. Behav Modif. 2014:38(4):497–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicholas J, Fogarty AS, Boydell K, Christensen H. The reviews are in: A qualitative content analysis of consumer perspectives on apps for bipolar disorder. J Med Internet Res. 2017:19(4):e105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai S, Dell’Elce J, Tucci N, Fuhrer R, Tamblyn R, Malla A. Preferences of young adults with first-episode psychosis for receiving specialized mental health services using technology: A survey study. JMIR Ment Heal. 2015:2(2):e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Firth J, Torous J. Smartphone apps for schizophrenia: A systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015:3(4):e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell IH, Lim MH, Rossell SL, Thomas N. Ecological momentary assessment and intervention in the treatment of psychotic disorders: A systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2017:68:1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoeppner BB, Schick MR, Kelly LM, Hoeppner SS, Bergman B, Kelly JF. There is an app for that – Or is there? A content analysis of publicly available smartphone apps for managing alcohol use. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017:82:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohn AM, Hunter-Reel D, Hagman BT, Mitchell J. Promoting behavior change from alcohol use through mobile technology: The future of ecological momentary assessment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011:35(12):2209–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savic M, Best D, Rodda S, Lubman DI. Exploring the focus and experiences of smartphone applications for addiction recovery. J Addict Dis. 2013:32(3):310–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weaver ER, Horyniak DR, Jenkinson R, Dietze P, Lim MSC. Let’s get wasted! and other apps: Characteristics, acceptability, and use of alcohol-related smartphone applications. J Med Internet Res. 2013:15(6):e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choo CC, Burton AAD. Mobile Phone apps for behavioral interventions for at-risk drinkers in Australia: Literature review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018:6(2):e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quanbeck A, Chih M-Y, Isham A, Johnson R, Gustafson D. Mobile delivery of treatment for alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res. 2014:36(1):111–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milward J, Khadjesari Z, Fincham-Campbell S, Deluca P, Watson R, Drummond C. User preferences for content, features, and style for an app to reduce harmful drinking in young adults: Analysis of user feedback in app stores and focus group interviews. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2016:4(2):e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazemi DM, Borsari B, Levine MJ, Li S, Lamberson KA, Matta LA. A systematic review of the mHealth interventions to prevent alcohol and substance abuse. J Health Commun. 2017:22(5):413–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fowler LA, Holt SL, Joshi D. Mobile technology-based interventions for adult users of alcohol: A systematic review of the literature. Addict Behav. 2016:62:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berman AH, Gajecki M, Sinadinovic K, Andersson C. Mobile interventions targeting risky drinking among university students: A review. Curr Addict Reports. 2016:3(2):166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Rourke L, Humphris G, Baldacchino A. Electronic communication based interventions for hazardous young drinkers: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016:68:880–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meredith SE, Alessi SM, Petry NM. Smartphone applications to reduce alcohol consumption and help patients with alcohol use disorder: A state-of-the-art review. Adv Heal Care Technol. 2015:1:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bennett ME, Toffey K, Dickerson F, Himelhoch S, Katsafanas E, Savage CLG. A review of android apps for smoking cessation. J Smok Cessat. 2015:10(2):106–15. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Regmi K, Kassim N, Ahmad N, Tuah NA. Effectiveness of mobile apps for smoking cessation: A review. Tob Prev Cessat. 2017:3(April):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whittaker R, Borland R, Bullen C, Lin RB, McRobbie H, Rodgers A, et al. Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:4(4):1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thornton L, Quinn C, Birrell L, Guillaumier A, Shaw B, Forbes E, et al. Free smoking cessation mobile apps available in Australia: A quality review and content analysis. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017:41(6):625–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.•.Haskins BL, Lesperance D, Gibbons P, Boudreaux ED. A systematic review of smartphone applications for smoking cessation. Transl Behav Med. 2017:7(2):292–9.Describes specific smoking cessation apps with discussion of features and evidence.

- 55.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. 2018. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/index.html

- 56.Hoeppner BB, Hoeppner SS, Seaboyer L, Schick MR, Wu GWY, Bergman BG, et al. How smart are smartphone apps for smoking cessation? A content analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016:18(5):1025–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abroms LC, Lee Westmaas J, Bontemps-Jones J, Ramani R, Mellerson J. A content analysis of popular smartphone apps for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med. 2013:45(6):732–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abroms LC, Padmanabhan N, Thaweethai L, Phillips T. iPhone apps for smoking cessation: A content analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2011:40(3):279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ferron JC, Brunette MF, Geiger P, Marsch LA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Bartels SJ. Mobile phone apps for smoking cessation: Quality and usability among smokers With psychosis. JMIR Hum Factors. 2017:4(1):e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heminger C, Schindler-Ruwisch J, Lorien Abroms L. Smoking cessation support for pregnant women: role of mobile technology. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016:7:15–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coulon SM, Monroe CM, West DS. A systematic, multi-domain review of mobile smartphone apps for evidence-based stress management. Am J Prev Med. 2016:51(1):95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Proudfoot J, Parker G, Pavlovic DH, Manicavasagar V, Adler E, Whitton A. Community attitudes to the appropriation of mobile phones for monitoring and managing depression, anxiety, and stress. J Med Internet Res. 2010:12(5):e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wallace LS, Dhingra LK. A systematic review of smartphone applications for chronic pain available for download in the United States. J Opioid Manag. 2014:10(1):63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Portelli P, Eldred C. A quality review of smartphone applications for the management of pain. Br J Pain. 2016:10(3):135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lalloo C, Jibb LA, Rivera J, Agarwal A, Stinson JN, “There’s a pain app for that”: Review of patient-targeted smartphone applications for pain management. Clin J Pain. 2015:31(6):557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De La Vega R, Miró J. mHealth: A strategic field without a solid scientific soul. A systematic review of pain-related apps. PLoS One. 2014:9(7):e101312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhattarai P, Newton-John T, Phillips JL. Quality and usability of arthritic pain self-management apps for older adults: A systematic review. Pain Med. 2017:19:471–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Machado GC, Pinheiro MB, Lee H, Ahmed OH, Hendrick P, Williams C, et al. Smartphone apps for the self-management of low back pain: A systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016:30(6):1098–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grist R, Porter J, Stallard P. Mental health mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017:19(5):e176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moussa Y, Mahdanian AA, Yu C, Segal M, Looper KJ, Vahia IV, et al. Mobile health technology in late-life mental illness: A focused literature review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017:25(8):865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dubad M, Winsper C, Meyer C, Livanou M, Marwaha S. A systematic review of the psychometric properties, usability and clinical impacts of mobile mood-monitoring applications in young people. Psychol Med. 2018:48(2):208–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.•.Bry LJ, Chou T, Miguel E, Comer JS. Consumer smartphone apps marketed for child and adolescent anxiety: A systematic review and content analysis. Behav Ther. 2018:49(2):249–261.Reviews current child and adolescent anxiety apps, including clinical implications and future technological directions.

- 73.Seko Y, Kidd S, Wiljer D, McKenzie K. Youth mental health interventions via mobile phones: A scoping review. Cyberpsychology, Behav Soc Netw. 2014:17(9):591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mani M, Kavanagh DJ, Hides L, Stoyanov SR. Review and evaluation of mindfulness-based iPhone apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015:3(3):e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rathbone AL, Clarry L, Prescott J. Assessing the efficacy of mobile health apps using the basic principles of cognitive behavioral therapy: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017:19(11):e399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Capon H, Hall W, Fry C, Carter A. Realising the technological promise of smartphones in addiction research and treatment: An ethical review. Int J Drug Policy. 2016:36:47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Giroux I, Goulet A, Mercier J, Jacques C, Bouchard S. Online and mobile interventions for problem gambling, alcohol, and drugs: A systematic review. Front Psychol. 2017:8:954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pospos S, Young IT, Downs N, Iglewicz A, Depp C, Chen JY, et al. Web-based tools and mobile applications To mitigate burnout, depression, and suicidality among healthcare students and professionals: A systematic review. Acad Psychiatry. 2018:42(1):109–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bakker D, Kazantzis N, Rickwood D, Rickard N. Mental health smartphone apps: Review and evidence-based recommendations for future developments. JMIR Ment Heal. 2016:3(1):e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bateman DR, Srinivas B, Emmett TW, Schleyer TK, Holden RJ, Hendrie HC, et al. Categorizing health outcomes and efficacy of mHealth apps for persons with cognitive impairment: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017:19(8):e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Christensen H, Petrie K. State of the e-mental health field in Australia: Where are we now? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013:47(2):117–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Donker T, Petrie K, Proudfoot J, Clarke J, Birch MR, Christensen H. Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2013:15(11):e247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lui JHL, Marcus DK, Barry CT. Evidence-based apps? A review of mental health mobile applications in a psychotherapy context. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2017:48(3):199–210. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Menon V, Rajan T, Sarkar S. Psychotherapeutic applications of mobile phone-based technologies: A systematic review of current research and trends. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017:39(1):4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rathbone AL, Prescott J. The use of mobile apps and SMS messaging as physical and mental health interventions: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017:19(8):e295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Runyan JD, Steinke EG. Virtues, ecological momentary assessment/intervention and smartphone technology. Front Psychol. 2015:6:481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dogan E, Sander C, Wagner X, Hegerl U, Kohls E. Smartphone-based monitoring of objective and subjective data in affective disorders: Where are we and where are we going? Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017:19(7):e262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hollis C, Falconer C, Martin J, Whittington C, Stockton S, Glazebrook C, et al. Annual research review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems: a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017:58(4):474–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meyer TD, Casarez R, Mohite SS, La Rosa N, Iyengar MS. Novel technology as platform for interventions for caregivers and individuals with severe mental health illnesses: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018:226:169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sucala M, Schnur JB, Glazier K, Miller SJ, Green JP, Montgomery GH. Hypnosis-there’s an app for that: A systematic review of hypnosis apps. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2013:61(4):463–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ghorai K, Akter S, Khatun F, Ray P. mHealth for smoking cessation programs: A systematic review. J Pers Med. 2014:4(3):412–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lyzwinski LN, Caffery L, Bambling M, Edirippulige S. A systematic review of electronic mindfulness-based therapeutic interventions for weight, weight-related behaviors, and psychological stress. Telemed e-Health. 2017:24(3):173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]