Abstract

We present the case of an 80-year old man taking rivaroxaban for atrial fibrillation who sustained massive intra-abdominal bleeding in the setting of acute cholecystitis. CT scan on admission revealed evidence of active bleeding into the gallbladder lumen and gallbladder perforation. Immediate resuscitation was commenced with intravenous fluids, antibiotics and blood products. Despite attempts to correct coagulopathy, the patient’s haemodynamic status deteriorated and an emergency laparotomy was performed, with open cholecystectomy, washout and haemostasis. The patient had a largely uneventful recovery and was discharged on day 11 of admission. Patients with coagulopathies, whether pharmacological or due to underlying disease processes, are at very high risk of severe haemorrhagic complications and subsequent morbidity. As such, prompt recognition and operative management of haemorrhagic perforated cholecystitis is of crucial importance.

Keywords: general surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, haematology (drugs and medicines), contraindications and precautions

Background

Gallbladder perforation occurs in 2%–15% of cases of acute cholecystitis, with a mortality rate of up to 42%.1 It is an uncommon but life-threatening condition which usually requires immediate surgical intervention.2 The most common site of gallbladder perforation is the fundus, owing to it being furthest away from the cystic artery and hence being the least well-vascularised part of the organ.3 4 Diagnosis can be challenging because it can occur in the presence or absence of gallstones and as such is rarely detected preoperatively.5 6 Even more rare is spontaneous non-variceal intra-abdominal bleeding caused by acute cholecystitis, with less than 10 cases reported in the available literature.1 There are a number of possible mechanisms by which this may occur, but all known cases have occurred in the presence of antiplatelet or anticoagulant use or an underlying bleeding diathesis.

We present the case of an elderly man on oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation who experienced massive intra-abdominal bleeding in the setting of acute cholecystitis with free rupture of gallbladder contents into the peritoneal cavity.

Case presentation

An 80-year-old man with a history of atrial fibrillation, bioprosthetic aortic valve, permanent pacemaker, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia presented to the emergency department with a 4-hour history of severe, sudden-onset right upper quadrant pain which progressed to more diffuse right-sided abdominal pain. He had no vomiting or nausea and no subjective fevers. His regular medications included antihypertensives, lipid-lowering agents and an anticoagulant (rivaroxaban) which he had taken 12 hours prior to presentation. He had no prior history of similar symptoms.

Clinical examination revealed a diaphoretic-appearing patient with right-sided peritonism, heart rate of 71 beats/min (bpm), blood pressure 171/96 mm Hg, temperature 36.6°C and oxygen saturations of 95% on room air.

Investigations

Relevant biochemical findings included a haemoglobin of 15.5g/dL, leucocyte count 19.57×109/L, international normalised ratio (INR) 2.0, ɣ-glutamyl transferase 403 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 180 U/L, alanine transaminase 191 U/L, aspartate transaminase 454 U/L and C reactive protein 31 mg/L. INR was 2.0 reflecting significant coagulopathy.

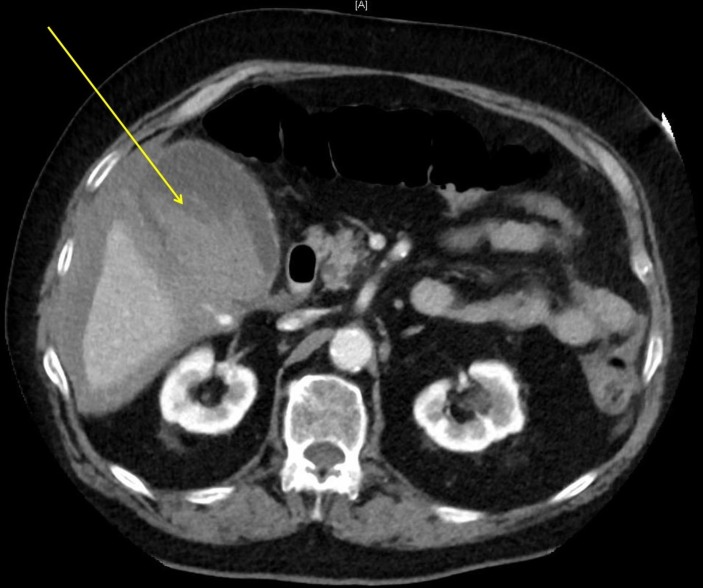

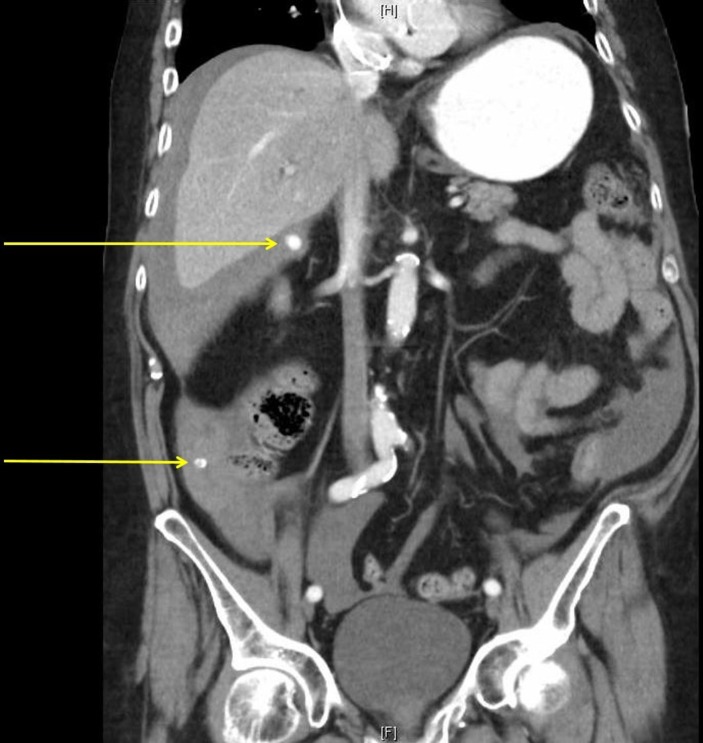

CT was preferred as the initial imaging modality due to the lack of availability of ultrasound in our institution at that time of the day. It revealed a large amount of free intraperitoneal fluid and a distended gallbladder with active extravasation of intravenous contrast into the lumen (figure 1) which was not present on the non-contrast phase (figure 2). There were also two calcified gallstones lying outside of the gallbladder (figures 3 and 4), consistent with a perforated gallbladder and active arterial bleeding.

Figure 1.

Axial slice of CT abdomen with intravenous contrast in the portal venous phase demonstrating high-density fluid (blood) within the gallbladder (indicating haemorrhage into its lumen) and peritoneal cavity (arrow).

Figure 2.

Axial slice of non-contrast CT abdomen demonstrating free fluid within the peritoneal cavity without enhancement of the fluid within the gallbladder.

Figure 3.

Coronal slice of intravenous contrast-enhanced CT abdomen demonstrating free abdominal fluid and two calcified gallstones lying outside the gallbladder (arrows).

Figure 4.

Sagittal slice of intravenous contrast-enhanced CT abdomen demonstrating a calcified extraluminal gallstone sitting within Morrison’s (hepatorenal) pouch (arrow).

Treatment

We resuscitated the patient, initially with warmed intravenous fluids and later with blood products when they became available. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics were started (ampicillin, gentamicin and metronidazole) with planned laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 12 hours (ie, to allow for metabolism of the anticoagulant for 24 hours since his last dose). Intensive care review was requested due to the status of the patient and his potential for clinical deterioration, and he was transferred to their unit. Haematologist advice was sought and as a result he was administered 5000 units of Prothrombinex-VF (CSL Behring; contains concentrated human factors II, IX, X and small amounts of factor V and VII calculated at approximately 50 units/kg) in order to reverse his coagulopathy. Despite partial correction of INR to 1.8, the patient became tachycardic (98 bpm) and hypothermic (34.2°C) several hours later with an associated tachypnoea (30 bpm) and worsening oxygen saturations (94% on 2 L/min supplemental oxygen via nasal prongs). There was a drop in haemoglobin to 102 g/L resulting in activation of the massive transfusion protocol and subsequent administration of 4 units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma (FFP).

The patient continued to deteriorate acutely over the next 30 min which necessitated urgent surgical intervention, despite only being off his anticoagulation for less than 24 hours. Owing to the haemodynamic status of the patient and the lack of availability, angioembolisation was not considered a viable option. The patient was taken for emergency laparotomy, at which time approximately 1500 mL of blood was found in the peritoneal cavity. Active bleeding was encountered from the perforated wall of the fundus of the gallbladder. A cholecystectomy and normal saline washout were performed with evacuation of blood clot, bile and gallstones. Prophylactic subcutaneous heparin (5000 units twice daily) was commenced the following day but therapeutic anticoagulation (enoxaparin 80 mg bd) for atrial fibrillation was withheld for a further 5 days to reduce the likelihood of postoperative bleeding.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged on day 11 of admission after being treated for a hospital-acquired pneumonia but required no further surgical intervention and no further blood transfusions. Haemoglobin on discharge was 99 g/L.

Histological examination revealed features of acute cholecystitis, with inflammatory slough present on the mucosal surface. There was marked neutrophilic, lymphocytic and fibroblastic proliferation with no evidence of dysplasia or malignancy.

Discussion

Gallbladder perforation as a result of acute calculous cholecystitis is thought to arise from occlusion of the cystic duct which causes a rise in intraluminal pressure, ultimately impeding venous and lymphatic drainage such that there is progression to ischaemia and necrosis of the gallbladder wall with subsequent perforation.5 7 8 Predisposing factors include trauma, malignancy, diabetes, age over 60 years, male gender, atherosclerosis, immunosuppression and long-term steroid usage.2 5 9 However, perforation can also occur in the setting of acalculous cholecystitis and is then associated with liver abscesses, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) infection and recent administration of oxaliplatin chemotherapy.2 10 There is one case report of spontaneous gallbladder perforation resulting from focal ischaemia in the absence of histological evidence of acute inflammation.3

A three-tiered classification of gallbladder perforation has been previously described: acute ‘free’ perforation, subacute perforation leading to subhepatic abscess formation and chronic perforation with formation of a cholecystoenteric or cholecystoenteric fistula.9 Preoperative diagnosis can be challenging but has been described using ultrasound, CT or nuclear medicine techniques.8 9 11 The ‘hole sign’ on ultrasound refers to direct visualisation of the defect in the gallbladder wall, although identification of calculi outside the gallbladder wall and demonstration of flow (on colour Doppler) between the gallbladder lumen and the pericholecystic abscess are two other confirmatory signs.11 Presence of radiolabelled tracer outside the biliary system on cholescintigraphy has also been described.9

Haemorrhagic cholecystitis with subsequent gallbladder rupture and torrential bleeding is a very rare but life-threatening complication of acute biliary tract disease.6 Bleeding in this setting is thought to arise from one of a number of mechanisms: acute cholecystitis with perforation and subsequent bleeding from the defect in the wall of the gallbladder, spontaneous bleeding into the lumen of the gallbladder with subsequent rupture due to increased intraluminal pressure or transhepatic perforation of the gallbladder.1 6 7 The last of these refers to bleeding from pressure necrosis of the liver due to gallstones which have eroded through the gallbladder wall and into the liver parenchyma.7 Findings on CT scan are diagnostic and include the presence of high-density pericholecystic fluid containing gallstones and active extravasation of intravenous contrast into a gallbladder containing hyperdense fluid.6 8 12 Predictably, the main risk factor for haemorrhagic cholecystitis is anticoagulant use or an underlying bleeding diathesis, with all previous known cases occurring in patients taking aspirin, warfarin or suffering from a bleeding disorder such a haemophilia.1 6 12–15 Our patient had been on rivaroxaban, a highly selective direct factor Xa inhibitor which is rapidly absorbed, has maximum serum concentrations within 2–4 hours of oral administration and a half-life of 5–13 hours.16 At the time of writing, there were no known commercially available reversal agents for direct factor Xa inhibitors.

CT-guided angioembolisation is a relevant option in patients with high anaesthetic risk but availability is institution and time dependent.1 As our case demonstrates, surgery often remains the only immediately available therapy for patients suffering from haemorrhagic perforated cholecystitis.

Learning points.

Haemorrhagic cholecystitis with gallbladder perforation is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition. Clinical recognition can be challenging but CT is usually diagnostic.

With more direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) agents becoming available and increasing numbers of patients being prescribed them, clinicians need to exercise a high level of suspicion to exclude an adverse bleeding event.

Immediate or early surgery should be considered and may be the only therapeutic option if interventional radiology services are not available.

Early haematology advice should be obtained for patients who have suffered a bleeding event while on a DOAC and, if available, a reversal agent should be administered.

Footnotes

Contributors: AK was the primary author of the manuscript and was involved in the patient’s postoperative care. TYC assisted in the writing of the initial draft of the manuscript. RW was the primary surgeon involved in the patient’s care and was responsible for proof-reading the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mechera R, Graf K, Oertli D, et al. Gallbladder perforation and massive intra-abdominal haemorrhage complicating acute cholecystitis in a patient with haemophilia A. BMJ Case Rep. Published online 2015;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun Y, Song W, Hou Q, et al. Gallbladder perforation: a rare complication of postoperative chemotherapy of gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2015;13:245 10.1186/s12957-015-0659-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura T, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Spontaneous gallbladder perforation without acute inflammation or gallstones. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean DE, Jamison JM, Lane JL. Spontaneous rupture of the gall bladder: an unusual forensic diagnosis. J Forensic Sci 2014;59:1142–5. 10.1111/1556-4029.12436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan SA, Gulfam M, Anwer AW, et al. Gallbladder perforation: a rare complication of acute cholecystitis. J Pak Med Assoc 2010;60:228–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavernaraki K, Sykara A, Tavernaraki E, et al. Massive intraperitoneal bleeding due to hemorrhagic cholecystitis and gallbladder rupture: CT findings. Abdom Imaging 2011;36:565–8. 10.1007/s00261-010-9672-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nural MS, Bakan S, Bayrak IK, et al. A rare complication of acute cholecystitis: transhepatic perforation associated with massive intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Emerg Radiol 2007;14:439–41. 10.1007/s10140-007-0621-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YC, Park MS, Chung YE, et al. Gallstone spillage caused by spontaneously perforated hemorrhagic cholecystitis. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:5525–6. 10.3748/wjg.v13.i41.5525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson DG, Lieberman LM. Perforation of the gallbladder diagnosed preoperatively. Eur J Nucl Med 1983;8:145–7. 10.1007/BF00252883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheridan D, Qazi A, Lisa S, et al. Spontaneous acalcuilous gallbladder perforation. BMJ Case Rep. Published online 2014;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indiran V, Prabakaran N, Kannan K. “Hole sign” of the gallbladder. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology 2017;36:66–7. 10.1007/s12664-016-0723-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandya R, O’Malley C. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis as a complication of anticoagulant therapy: role of CT in its diagnosis. Abdom Imaging 2008;33:652–3. 10.1007/s00261-007-9358-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YY, Yi CH, Chen CL, et al. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis after anticoagulation therapy. Am J Med Sci 2010;340:338–9. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e9563e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vijendren A, Cattle K, Obichere M. Spontaneous haemorrhagic perforation of gallbladder in acute cholecystitis as a complication of antiplatelet, immunosuppressant and corticosteroid therapy. BMJ Case Rep 2012doi: bcr1220115427 10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onishi S, Hojo N, Sakai I, et al. Rupture of the gallbladder in a patient with acquired factor VIII inhibitors and systemic lupus erythematosus. Intern Med 2004;43:1073–7. 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivaroxaban product information. https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2009-PI-01020-3&d=2018062016114622483 (Accessed 2 Jun 2018).