Abstract

Water-deficit stress tolerance in rice is important for maintaining stable yield, especially under rain-fed ecosystem. After a thorough drought-tolerance screening of more than 130 rice genotypes from various regions of Koraput in our previous study, six rice landraces were selected for drought tolerance capacity. These six rice landraces were further used for detailed physiological and molecular assessment under control and simulated drought stress conditions. After imposing various levels of drought stress, leaf photosynthetic rate (PN), photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm), SPAD chlorophyll index, membrane stability index and relative water content were found comparable with the drought-tolerant check variety (N22). Compared to the drought-susceptible variety IR64, significant positive attributes and varietal differences were observed for all the above physiological parameters in drought-tolerant landraces. Genetic diversity among the studied rice landraces was assessed using 19 previously reported drought tolerance trait linked SSR markers. A total of 50 alleles with an average of 2.6 per locus were detected at the loci of the 19 markers across studied rice genotypes. The Nei’s genetic diversity (He) and the polymorphism information content (PIC) ranged from 0.0 to 0.767 and 0.0 to 0.718, respectively. Seven SSR loci, such as RM324, RM19367, RM72, RM246, RM3549, RM566 and RM515, showed the highest PIC values and are thus, useful in assessing the genetic diversity of studied rice lines for drought tolerance. Based on the result, two rice landraces (Pandkagura and Mugudi) showed the highest similarity index with tolerant check variety. However, three rice landraces (Kalajeera, Machhakanta and Haldichudi) are more diverse and showed highest genetic distance with N22. These landraces can be considered as the potential genetic resources for drought breeding program.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12298-018-0606-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Drought tolerance, Landraces, Photosynthetic rate, Relative water content, Simple sequence repeat

Introduction

Drought is the most important abiotic stress that affects rice productivity worldwide and is particularly more frequent in South and Southeast Asia (Pandey and Shukla 2015). In South and Southeast Asia, nearly 23 million hectares of rainfed rice cultivating area is drought-prone and affecting more than 50% of rice yield (Rahman and Zhang 2016). Breeding for drought tolerance is crucial for maintaining stable yield, especially under rainfed ecosystem. Due to the heterogeneity in the rainfed ecosystem, different types of traditional rice landraces are being cultivated by the farmers. These landraces that are more suited to rainfed conditions could be the sources of genetic variation, and used in drought breeding programs (Pandey et al. 2007; Vikram et al. 2016). Assessment of genetic diversity and genotypic variability to drought tolerance is an important requisite for a successful drought tolerance breeding programme (Abenavoli et al. 2016; Anower et al. 2017). Therefore, screening drought tolerant genotypes is becoming increasingly important (Pandey and Shukla 2015; Swapna and Shyalaraj 2017). Genetic resources serve as raw material for crop improvement (McCouch et al. 2013) and its success depends on the identification of true stress tolerance genotypes and gene mining strategies (Ismail et al. 2012).

The responses of rice plants to drought are believed to be complex that involves various physiological, biochemical and molecular changes (Lenka et al. 2011; Atkinson and Urwin 2012; Braga et al. 2015; Vikram et al. 2016). It affects crop growth by negatively affecting germination, seedling vigor, photosynthesis, leaf membrane stability and osmolyte content (Pandey and Shukla 2015). Simultaneously, many genes have been identified to be involved in response to drought stress in rice and other crops (Lenka et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2012). Expression of numerous genes during drought stress are reported to be collectively responsible for the drought tolerance. Thus, no single attribute of any physiological or molecular parameter is likely to increase crop productivity under drought stress (Kamoshita et al. 2008; Farooq et al. 2009). Earlier molecular genetics studies identified numerous QTLs (quantitative trait loci) linked to various physiological and biochemical traits (Venuprasad et al. 2009; Alexandrov et al. 2014; Todaka et al. 2015; Vikram et al. 2016), but no genes that regulate these traits have been identified because of low mapping resolution and weak phenotypic effects (Pandey and Shukla 2015; Singh et al. 2016; Rahman and Zhang 2016). The progress of drought tolerance breeding has been slow due to lack of true drought tolerant genotypes for the target environment and lack of suitable screening methods (Pandey and Shukla 2015; Rahman and Zhang 2016). Besides the DNA based molecular characterization, physiological performances under induced drought stresses are also necessary for the proper varietal identification to drought tolerance.

Koraput district of Odisha state of India is the home to a large number of traditional rice landraces. This region is considered as the secondary centre of origin of Asian cultivated (Aus) summer rice varieties (Arunachalam et al. 2006; Mishra and Panda 2017b). These landraces are likely to contain a considerable genetic diversity and the local farmers continue to rely on these landraces selected by their ancestors (Patra and Dhua 2003; Roy et al. 2017). Traditional landraces of rice are the reservoir of many useful genes but a vast majority of these genes remained untapped (Samal et al. 2018). The drought-tolerant accessions are predominately originated from aus accessions (Rahman and Zhang 2016). It is important to assess this diversity in order to design strategies for conservation and utilization in breeding programmes. Though the traditional rice landraces are less productive, these genotypes are reported to exhibit tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses (Sarkar and Bhattacharjee 2011). There is a dearth of phenotypic knowledge and molecular profiling reports of indigenous rice landraces of Koraput with respect to drought tolerance. Thus, the objectives of the study were to access the genetic diversity among selected traditional rice landraces of Koraput with respect to drought tolerance through physiological and molecular marker analysis. Further, this study aimed to determine their genetic relationships for utilization in breeding programs focused on drought tolerance.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The experiments were conducted using six selected traditional rice landraces of Koraput, India along with N22 (drought-tolerant upland rice variety) and IR64 (drought-susceptible irrigated variety) as check varieties. The details of the rice landraces and their specific characters are presented in Table 1. The traditional rice landraces of Koraput were obtained from MS Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF), Koraput and the drought tolerant and susceptible check varieties were obtained from ICAR-National Rice Research Institute (NRRI), Cuttack, India. These indigenous rice landraces were selected for in-depth study after initial drought tolerance screening of 130 rice genotypes, which were collected from various regions of Koraput, India (Mishra and Panda 2017a).

Table 1.

Details of rice genotypes with their special characters collected from the traditional growers of Koraput

| Variety | Area of collection | Special characters |

|---|---|---|

| Kalajeera | Koraput | Lowland variety with long duration of maturity (140–150 days), highly aromatic with black husk color, drought tolerant |

| Dangarabayagundar | Koraput | Upland variety with short duration of maturity (103 days), medium and bold grain, white grain, drought escaping |

| Mugudi | Koraput | Lowland variety with medium duration of maturity (130–135 days), strong straw, bold kernel, drought tolerant |

| Machhakanta | Koraput | Lowland variety with long duration of maturity (135–145 days), good grain quality, popular variety, drought tolerant |

| Haladichudi | Koraput | Medium land variety with medium duration of maturity (125–135 days), medium slender grain, deep yellow husk color, popular variety, drought tolerant |

| Pandakagura | Koraput | Upland variety with long duration of maturity (145–150 days), white grain, coarse white rice, drought tolerant |

| N 22 | Uttar Pradesh, India | Upland variety with short duration of maturity (80–95 days), deep-rooted, drought tolerant rice variety (a selection from ‘Rajbhog’) |

| IR 64 | IRRI, Philippines | Lowland variety with short duration of maturity (115 days), high yielding, long slender grain, rainfed lowland area, susceptible to drought stress |

Physiological evaluation of rice landraces

The experiments were conducted in the laboratory of the Central University of Orissa, Koraput (82°44′54″ E to 18°46′47″ N and 880 m above the mean sea level) during March to May 2017. The maximum air temperature and relative humidity were about 33.6 ± 2 °C and 65–75%, respectively during the experiments. Uniform sized seeds of each variety were selected and treated at 48 ± 2 °C for 5 days to break the dormancy. Prior to the experiment, seeds were surface sterilized with 0.1% HgCl2 solution for 5 min and thoroughly washed with distilled water. The seeds were placed in sterilized Petri plates over water-saturated Whatman paper and kept in an incubator with a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod with daily maximum photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) ~ 390 ± 40 µ mol m−2 s−1 at 25 °C in the laboratory, as described by Mishra and Panda (2017b). Uniformly germinated seeds after 5 days were selected and transferred to plastic pots containing Yoshida nutrient medium (Yoshida 1976). After 30 days of normal growth in Yoshida nutrient medium, the plants were subjected to drought stress by application of (36.0%) of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-6000 that produces − 1.5 MPa water potential for 10 days. The solution was replaced every 5th day and the pH was constantly maintained at 5.0. A control set (without application of PEG) was also run along with the PEG treatment. The experiment was laid out in a randomized complete-block design with three replications.

Measurement of photosynthetic rate, maximum photochemical efficiency of PS II and SPAD chlorophyll index

The leaf CO2 photosynthetic rate (PN) was measured using an open system photosynthetic gas analyzer (CI-304, CID, USA) between 10 and 11 h by taking 2nd leaf from the top of control and drought-treated plants of each replicate. The leaf was kept inside the chamber under natural irradiance until a stable reading was recorded. The measurements were carried out at 32 ± 3 °C, 60–70% Relative humidity, 1121 ± 29 μmol m−2 s−1 photosynthetic active radiation, 370 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1 and 21% O2.

After measurement of photosynthetic rate, the same leaf was used for the measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence in 20 min dark-adapted leaves by using a portable chlorophyll fluorometer (JUNIOR-PAM, WALZ, Germany). Different parameters like minimal fluorescence (Fo), maximal fluorescence (Fm) and variable fluorescence (Fv = Fm-Fo) were measured and used for calculation of maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) (Maxwell and Johnson 2000).

After measurement of the photosynthetic rate and chlorophyll fluorescence, the same leaves were used for measurement of SPAD chlorophyll index by using the SPAD 502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta Sensing, Inc., Osaka, Japan).

Determination of relative water content (RWC) and membrane stability index (MSI)

The relative water content was estimated by taking fully matured leaves of each plant and immediately weighed for taking the leaf fresh weight (Fwt). Then it was immersed in deionised water for 48 h in dark. Subsequently, the sample was again weighed to measure the leaf turgid weight (Twt). Then the leaf was placed in an oven at 70 °C for 48 h to determine the leaf dry weight (Dwt). The RWC of the leaf was calculated according to Abenavoli et al. (2016).

The Membrane stability index (MSI) was measured by taking 0.1 g of leaf sample in two sets of test tubes containing 10 ml of distilled water. Test tubes of one set were heated in a water bath at 40 °C for 30 min and electrical conductivity was measured as C1. Test tubes of the second set were heated in a water bath at 100 °C for 15 min and electrical conductivity of the water containing the sample was measured as C2. The MSI was determined by the following formula given by Sairam (1994):

Determination of Malondialdehyde (MDA) content

Lipid peroxidation was measured in terms of MDA (Malondialdehyde) determined by Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) reactions followed by Heath and Packer (1968). Leaf sample (0.1 g) was homogenized in 5 ml of 0.1% (w/v) TCA (Trichloroacetic Acid) in a chilled mortar and pestle. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min and MDA content was determined by adding 1.0 ml of supernatant extract and was mixed with 1 ml of 0.5% (w/v) Thiobarbituric Acid solution in 20% (w/v) TCA. The mixture was then heated in a water bath at 95 °C for 30 min. Then the content was cooled and centrifuged at 10,000g for 15 min and the absorbance was measured at 532 nm and corrected for 600 nm and the concentration of MDA was expressed as nmol g−1 Fwt by using E = 155 mM−1 cm−1.

Molecular analysis through drought tolerance linked rice microsatellite loci

Molecular profiling of the studied genotypes was done by taking 19 reported simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers linked to different drought tolerance QTL in rice chromosomes (Bernier et al. 2007; Vikram et al. 2011, 2016) (Table 2). The sequence information of these markers was collected from Gramene database (www.gramene.org). The primer pairs were subjected to Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) in Gramene database for confirmation of their sequence complementarities in the rice genome.

Table 2.

Details of reported SSR markers linked to the drought tolerance QTL, which are used for molecular profiling of indigenous rice landraces

| Sl. | Primer | Expected PCR product size ≠ | QTL | Chromosome | PVE (%) | Repeat motive | Primers (F-forward, R-reverse) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RM11943 | 133 | qDTY1.1 | 1 | 17.0 | (GA)11 | F- CTTGTTCGAGGACGAAGATAGGG R- CCAGTTTACCAGGGTCGAAACC |

Vikram et al. (2011) |

| 2 | RM431 | 251 | qDTY1.1 | 1 | 32.0 | (AG)16 | F- TCCTGCGAACTGAAGAGTTG R- AGAGCAAAACCCTGGTTCAC |

Ghimire et al. (2012) |

| 3 | RM246 | 116 | qDPR1.1 | 1 | 9.00 | (CT)20 | F- GAGCTCCATCAGCCATTCAG R- CTGAGTGCTGCTGCGACT |

Ghimire et al. (2012) |

| 4 | RM315 | 133 | qDTY1.2 | 1 | 7.00 | (AT)4 (GT)10 |

F- GAGGTACTTCCTCCGTTTCAC R- AGTCAGCTCACTGTGCAGTG |

Sandhu et al. (2014) |

| 5 | RM324 | 175 | qDTY2.1 | 2 | 6.90 | (CAT)21 | F- CTGATTCCACACACTTGTGC R- GATTCCACGTCAGGATCTTC |

Dixit et al. (2012) |

| 6 | RM3549 | 168 | qDTY2.1 | 2 | 6.90 | (GA)12 | F- GATCCTCCACACCCAACAAC R- AACGAACGACCAACTCCAAG |

Dixit et al. (2012) |

| 7 | RM279 | 174 | qDTY2.2 | 2 | 11.0 | (GA)16 | F- GCGGGAGAGGGATCTCCT R- GGCTAGGAGTTAACCTCGCG |

Swamy et al. (2013) |

| 8 | RM555 | 223 | qDTY2.2 | 2 | 10.2 | (AG)11 | F- TTGGATCAGCCAAAGGAGAC R- CAGCATTGTGGCATGGATAC |

Dixit et al. (2012) |

| 9 | RM416 | 114 | qDTY3.1 | 3 | 15.0 | (GA)9 | F- GGGAGTTAGGGTTTTGGAGC R- TCCAGTTTCACACTGCTTCG |

Dixit et al. (2014) |

| 10 | RM16030 | 99 | qDTY3.1 | 3 | 27.0 | (AG)11 | F- GCGAACTATGAGCATGCCAACC R- GGATTACCTGGTGTGTGCAGTGTCC |

Shamsudin et al. (2016) |

| 11 | RM19367 | 112 | qDTY6.1 | 6 | 32.3 | (ACG)7 | F- CGTCATGTCGCGGAGGTAAGC R- AGGCGTACGTGGAGCAGAGTGC |

Venuprasad et al. (2012) |

| 12 | RM3805 | 110 | qDTY6.1 | 6 | 32.3 | (GA)19 | F- AGAGGAAGAAGCCAAGGAGG R- CATCAACGTACCAACCATGG |

Venuprasad et al. (2012) |

| 13 | RM72 | 166 | qDLR8.1 | 8 | 9.15 | (TAT)5C (ATT)15 |

F- CCGGCGATAAAACAATGAG R- GCATCGGTCCTAACTAAGGG |

Qu et al. (2008) |

| 14 | RM344 | 163 | qDRL8 | 8 | 4.26 | (TTC)2-5-(CTT)3-(CTT)4 | F- CAGAGACAATAGTCCCTGCAC R- GTAGGAGGAGATGGATGATGG |

Lang et al. (2013) |

| 15 | RM515 | 211 | qDTR8 | 8 | 4.35 | (GA)11 | F- TAGGACGACCAAAGGGTGAG R- TGGCCTGCTCTCTCTCTCTC |

Ramchander et al. (2016) |

| 16 | RM321 | 200 | qDTY9.1A | 9 | 19.0 | (CAT)5 | F- CCAACACTGCCACTCTGTTC R- GAGGATGGACACCTTGATCG |

Swamy et al. (2013) |

| 17 | RM566 | 239 | qDTY9.1A | 9 | 8.90 | (AG)15 | F- ACCCAACTACGATCAGCTCG R- CTCCAGGAACACGCTCTTTC |

Dixit et al. (2012) |

| 18 | RM17 | 184 | qDRW12 | 12 | 7.34 | (GA)21 | F- TGCCCTGTTATTTTCTTCTCTC R- GGTGATCCTTTCCCATTTCA |

Ramchander et al. (2016) |

| 19 | RM28166 | 194 | qDTY12.1 | 12 | 24.0 | (CT)12 | F- TGCTTGCAAACATTGCTTCTGG R- ACTGATGTACTGAACACGGGAAGG |

Mishra et al. (2013) |

PVE phenotypic variance explained; ≠ : source from Gramene database (www.gramene.org)

Isolation of genomic DNA

The isolation of total genomic DNA was carried out by a modified CTAB (Cetyl-Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide) method followed by Murray and Thompson (1980). Briefly, a total of 4 fresh leaves were collected from 15-days-old seedlings of each genotype. Isolated total DNA was dissolved in 50 μl of 1X TE (Tris–EDTA) buffer and stored in a − 20 °C freezer. The DNA quality and quantity were examined in a 0.8% Agarose gel in 1X TAE buffer at 70 V for 90 min and stained with Ethidium Bromide.

PCR amplification

For PCR amplification, 20 µl volumes was mixed with 2 µl of 10X PCR buffer, 0.3 µl of dNTP mixtures (10 mM), 2 µl of SSR primer (2 mM), 2 µl of genomic DNA (25 ng/µl), 0.2 µl of Taq polymerase (2U) and 12 µl of ddH2O, following the method given by Panaud et al. (1996). The PCR amplification included an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 20 s, annealing (depending on TM value of primer) at 60 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 45 s and a final extension of 10 min at 72 °C.

Polymorphism screening and analysis of amplified products

The amplified products were resolved through 2.5% ethidium Bromide stained (1 μg ml−1) agarose gel and documented using a gel documentation system (Alpha Imager, USA). The molecular weight of the amplified products (allelic variants) of the studied SSR markers was determined using analysis software supplied by the manufacturer. The different allelic forms (variation in molecular weight of the amplicons) of individual SSR loci were scored as 1 or 0 based on their presence or absence, respectively across the studied rice genotypes. A proximity matrix was constructed from the 1/0 matrix using PAST-3 (Palaeontological Statistics) software to construct a dendrogram using average linkage among the studied genotypes.

Polymorphic information content (PIC) for each SSR marker was calculated using the following formula (Hwang et al. 2009):

where, i = 1 to n and Pij is the frequency of jth allele for the ith band scored for a particular marker.

Marker-based genetic diversity parameters including effective number of alleles (Ne) (Kimura and Crow 1964), Shannon’s Information index (I) (Lewontin 1972) and Nei’s heterozygosity (He) (Nei 1973) was performed using genetic diversity analysis software POPGENE 1.31 (Yeh and Boyle 1997).

Statistical analysis

All physiological parameters were subjected to two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with the variety and different treatment levels being the main factors. Differences among treatments were compared via ANOVA using CROPSTAT (International Rice Research Institute, Philippines) software.

Results

Physiological performances of rice genotypes under drought stress

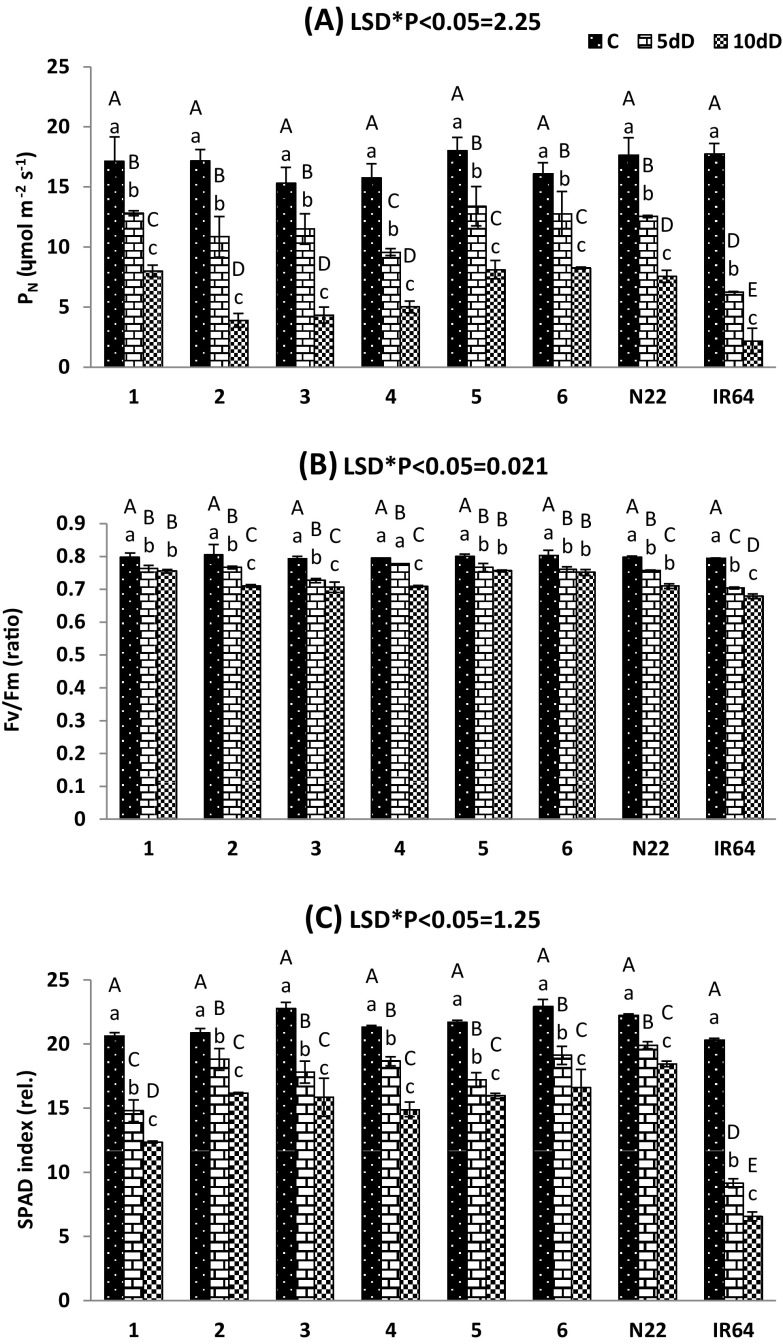

Changes in the photosynthetic performance of traditional rice landraces were studied by gas-exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements and the results were compared with the tolerant and susceptible check varieties under different durations of drought conditions (Fig. 1). A gradual decline in photosynthetic rate (PN) was observed in all the genotypes under drought stress. The differences in PN among studied genotypes were not significant under the control condition (Fig. 1a). However, significant variations were observed between the genotypes under 5 and 10 days of drought imposition. In particular, susceptible (IR64) variety exhibited sharp reductions of PN under different stresses compared to tolerant check variety (N22) and traditional landraces. However, the traditional landraces such as Kalajeera, Machhakanta and Haldichudi showed higher PN than that of N22 after 10 days of drought treatments. Similarly, a gradual reduction in leaf photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) was observed in all the genotypes under drought stress and significant (P < 0.05) varietal difference was observed during 5 and 10 days of drought treatments (Fig. 1b). The selected traditional landraces and tolerant variety (N22) exhibited a higher value of Fv/Fm under drought stress compared to the susceptible variety IR64. The traditional landraces such as Kalajeera, Machhakanta and Haldichudi showed higher Fv/Fm ratio than that of N22. In our study, drought stress (− 1.5 Mpa) significantly (P < 0.05) reduced SPAD chlorophyll index in the studied genotypes compared to the controls (Fig. 1c). In particular, susceptible (IR64) variety exhibited sharp reductions of SPAD index under drought stress compared to tolerant check N22 variety and traditional landraces.

Fig. 1.

Changes of CO2 photosynthetic rate (PN), maximum photochemical efficiency of PS II (Fv/Fm) and SPAD chlorophyll index of studied rice genotypes during control (C), 5 days of drought (5dD) and 10 days of drought (10dD) treatments. Data are the mean of three replications (n = 3) with vertical bar representing standard deviation. Means followed by the same uppercase and lowercase letter are not significantly different for variety and treatment respectively at the 5% level by Duncan’s multiple range test. LSD: least significance difference. Genotypes 1: Kalajeera; 2: Pandakagura; 3: Dandarbayagundar; 4: Mugudi; 5: Machhakanta 6: Haladichudi

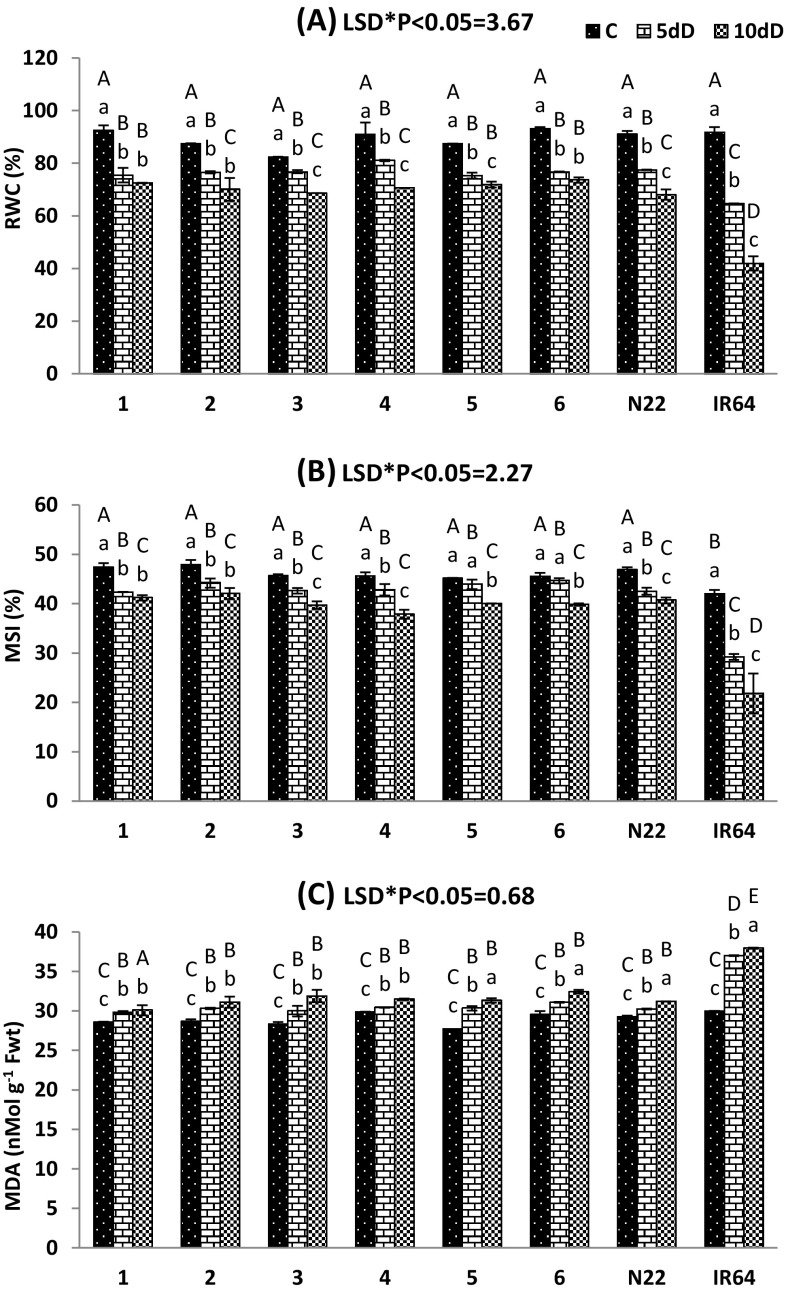

The relative water content (RWC) of rice genotypes remarkably declined under different durations (5 and 10 days) of drought treatment compared to the control and significant (P < 0.01) varietal difference was observed (Fig. 2a). Similarly, a significant (P < 0.05) variation of leaf membrane stability index (MSI) was also observed under different drought condition among the genotypes (Fig. 2b). The studied traditional rice landraces and tolerant check variety (N22) exhibited higher values of RWC and MSI under drought stress compared to the susceptible variety IR64 and proved to have their drought tolerance potential. More significantly, the landraces such as Kalajeera, Machhakanta and Haldichudi showed higher values of RWC than that of N22. A marked increase in lipid peroxidation product MDA content was recorded in the studied rice genotypes in response to different levels of drought stress and also significant (P < 0.01) varietal difference were observed (Fig. 2c). The MDA content was significantly higher in IR64 compared to other genotypes under drought stress. Among the traditional rice landraces, Kalajeera showed the lowest level of MDA content under drought treatment.

Fig. 2.

Changes of relative water content (RWC), membrane stability index (MSI) and lipid peroxidation content (MDA) of studied rice genotypes during control (C), 5 days of drought (5dD) and 10 days of drought (10dD) treatment. Data are the mean of three replications (n = 3) with vertical bar representing standard deviation. Means followed by the same uppercase and lowercase letter are not significantly different for variety and treatment respectively at the 5% level by Duncan’s multiple range test. LSD: least significance difference. Genotypes 1: Kalajeera; 2: Pandakagura; 3: Dandarbayagundar; 4: Mugudi; 5: Machhakanta; 6: Haladichudi

Molecular profiling of studied rice genotypes using SSRs linked with the drought tolerance trait

The results obtained through the analysis of eight rice genotypes with 19 SSR markers linked with drought tolerance QTL are presented in Table 2. Different alleles, in the form of variation in molecular weight of each amplified products for each SSR marker against studied eight genotypes, are given in Supplemental Fig. 1. The markers amplified a total of 50 alleles with an average of 2.6 per locus (Table 3). The markers RM324, RM72, RM515 and RM566 produced maximum (4 alleles), while RM315, RM19367, RM344 and RM321 generated only one allele across the studied eight lines. Among the used SSR’s, RM431 showed the highest range of allele size (200–250 bp). The observed allele numbers (Na) per locus and Nei’s gene diversity (He) ranged from 1 to 4 and 0 to 0.767, respectively. Among the studied 19 SSR markers, RM324, RM72 and RM515 showed the highest number of effective alleles accounting to 3.556. Shannon’s information index (I) of the studied SSR loci ranged from 0 to 1.321 with the highest (I) for RM324, RM72 and RM515 (1.321). If there is an abundance of only one type of allele, Shannon’s information Index approaches to zero, as revealed by RM315, RM19367, RM344 and RM321 having only 1 allele. The level of polymorphism among the 8 genotypes was evaluated by calculating polymorphism information content (PIC) values for each of the 19 SSR loci. The PIC value ranged from 0.0 to 0.718, with an average 0.465 per locus (Table 3). Amongst all SSR loci, seven SSR loci, such as RM324, RM19367, RM72, RM246, RM3549, RM566 and RM515 showed the higher PIC values and are important for evaluating the genetic diversity of rice genotypes for drought tolerance.

Table 3.

Genetic diversity parameters calculated on SSR data

| Locus | Size (bp) | Na | Ne | Ho | He | Nei’s | I | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM315 | 150 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 |

| RM11943 | 80–100 | 3 | 2.462 | 0.367 | 0.633 | 0.594 | 0.974 | 0.593 |

| RM431 | 200–250 | 3 | 2.462 | 0.367 | 0.633 | 0.594 | 0.974 | 0.593 |

| RM246 | 100–120 | 3 | 2.909 | 0.300 | 0.700 | 0.656 | 1.082 | 0.656 |

| RM324 | 150–190 | 4 | 3.556 | 0.233 | 0.767 | 0.719 | 1.321 | 0.718 |

| RM3549 | 150–170 | 3 | 2.462 | 0.367 | 0.633 | 0.594 | 0.974 | 0.625 |

| RM279 | 220–240 | 3 | 2.667 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.625 | 1.040 | 0.5 |

| RM555 | 100–130 | 2 | 2.000 | 0.467 | 0.533 | 0.500 | 0.693 | 0.593 |

| RM416 | 120 | 2 | 1.600 | 0.600 | 0.400 | 0.375 | 0.562 | 0 |

| RM16030 | 100–130 | 3 | 2.462 | 0.367 | 0.633 | 0.594 | 0.974 | 0.625 |

| RM19367 | 130–190 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.718 |

| RM3805 | 150 | 3 | 2.667 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.625 | 1.040 | 0 |

| RM72 | 190–210 | 4 | 3.556 | 0.233 | 0.767 | 0.719 | 1.321 | 0.718 |

| RM344 | 200 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 |

| RM515 | 210–240 | 4 | 3.556 | 0.233 | 0.767 | 0.719 | 1.321 | 0.656 |

| RM321 | 170–190 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.406 |

| RM566 | 210–240 | 4 | 2.909 | 0.300 | 0.700 | 0.656 | 1.213 | 0.656 |

| RM17 | 170–190 | 3 | 1.684 | 0.567 | 0.433 | 0.406 | 0.736 | 0.406 |

| RM28166 | 190–200 | 2 | 1.882 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.469 | 0.662 | 0.468 |

| Mean | 2.6 | 2.236 | 0.503 | 0.497 | 0.466 | 0.777 | 0.465 | |

| SD | 1.0463 | 0.853 | 0.275 | 0.275 | 0.258 | 0.457 | 0.257 |

Na number of alleles, Ne number of effective alleles, Ho expected homozygosity, He expected heterozygosity/Nei’s genetic diversity, I Shannon’s information index, PIC polymorphism information content

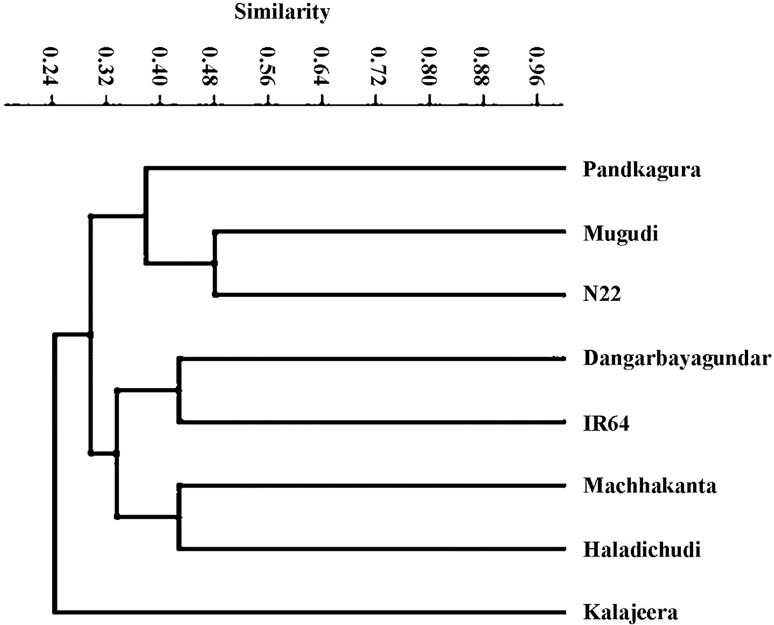

The pair-wise genetic similarity is the measure to identify the underlying genetic relationship among the genotypes. The pair-wise genetic similarity calculated for all the studied genotypes with 19 SSR markers ranged from 0.2 to 0.65 (Table 4). The traditional landraces such as Pandkagura and Mugudi showed higher genetic similarity with drought-tolerant check (N22) variety. In contrast, genetic distance ranged from 0.43 to 1.609 and the highest (1.609) was observed between Kalajeera and Pandkagura landraces (Table 4). However, the traditional landraces such as Kalajeera, Haldichudi and Machhakanta showed higher genetic distance with drought-tolerant check variety (N22) compared with other genotypes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Nei’s genetic identity (above diagonal) and genetic distance (below diagonal) between the studied rice genotypes on the basis of SSR profiling data

| Genotype | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| 2 | 1.6094 | – | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.55 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 0.9163 | 0.7985 | – | 0.5 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.6 |

| 4 | 0.9163 | 0.5978 | 0.6931 | – | 0.5 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 0.6931 | 0.9163 | 0.5978 | 0.6931 | – | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| 6 | 0.6931 | 0.6931 | 0.5978 | 0.5978 | 0.5108 | – | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| 7 | 1.0498 | 0.5978 | 0.7985 | 0.4308 | 1.204 | 1.204 | – | 0.5 |

| 8 | 1.0498 | 0.6931 | 0.5108 | 0.6931 | 0.9163 | 0.6931 | 0.6931 | – |

Genotypes 1: Kalajeera; 2: Pandakagura; 3:Dandarbayagundar; 4: Mugudi; 5: Machhakanta 6:Haladichudi; 7:N 22; 8:IR 64

Cluster analysis based on the Jaccard’s similarity paired linkage among studied rice genotypes were presented in Fig. 3. The Dendrogram showing the similarity forming two major clusters. The indigenous rice landraces Pandkagura and Mugudi along with drought-tolerant check N22 are in one cluster having more than 40% similarity. But Kalajeera was present in a separate cluster having more than 25% similarity with N22. The Dangarbayagundar landrace was very close to susceptible check variety (IR64), whereas Haldichudi and Machhakanta present in a separate sub-cluster having more than 30% similarity with N22.

Fig. 3.

Dendrogram showing the Jackard’s similarity index between the rice genotypes based on SSR amplified products

Discussion

To overcome the problems of drought stress in the present global scenario, there is an imperative need to characterize the traditional rice germplasm for drought tolerance (Venuprasad et al. 2009; Vikram et al. 2016). The Koraput region of Odisha (India) is endowed with a large assembly of traditional rice landraces and is the secondary center of origin of Asian cultivated rice. So, rice landraces collected from Koraput regions have greater potential to improve drought tolerance (Patra and Dhua 2003; Mishra and Panda 2017a, b). There is an imperative need to analyze the genetic diversity of landraces and genotypic variability to drought tolerance for a successful breeding programme (Abenavoli et al. 2016; Anower et al. 2017). The studied landraces having drought tolerance property with varying potentiality was earlier identified after rapid drought screening from 130 rice genotypes collected from various regions of Koraput (Mishra and Panda 2017a). These rice landraces were further used for detailed physiological and molecular assessment for proper characterization of rice lines in relation to drought tolerance.

Photosynthesis forms an important aspect of plant metabolism and balance sheet of growth and development, which is known to be sensitive to drought and water deficit (Gauthami et al. 2014). In this study, we evaluated the photosynthetic performance of the studied landraces of Koraput under different durations of drought. Leaf photosynthetic rate is one of the earliest parameter, responses to drought and it significantly decreased under drought in all the genotypes along with the decrease of SPAD chlorophyll index (Fig. 1). Like other abiotic stress, leaf photochemical efficiency of PS II (Fv/Fm) is one of the sensitive parameters in responses to drought (Mathobo et al. 2017; Strasser et al. 2004; Stirbet and Govindjee 2011). Drought also alters the PS II activity in rice, as reflected by a decrease in the values of Fv/Fm (Fig. 1). This was probably because of the antenna pigments disorganization (Calatayud et al. 2006) and a decrease of SPAD Chl index in the rice seedlings, as observed in drought stress (Fig. 1). The decrease of PN under drought was probably due to the structural and functional alteration of the photosynthetic apparatus as has been reported earlier in rice (Centritto et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2012). The main limitation to photosynthesis under drought condition was the closure of stomata as reported in rice (Gauthami et al. 2014). In the present study, SPAD index was remarkably declined under drought compared to control plants. In particular, susceptible (IR64) cultivar exhibited sharp reductions of SPAD index under drought stress compared to tolerant check (N22) variety and traditional landraces. A decrease in chlorophyll content due to drought stress has been reported in wheat (Talebi 2011), pea (Iturbe-Ormaetxe et al. 1998), chickpea (Mafakheri et al. 2010), soybean (Makbul et al. 2011) and rice (Lenka et al. 2011; Chutia and Borah 2012). These results were also consistent with earlier findings of chlorophyll reduction in rice seedlings under drought, which may be due to free radicals generated by these stresses (Mathobo et al. 2017; Mishra and Panda 2017b). The ability to maintain photosynthetic activity under water stress is one of the major factor for drought tolerance (Zlatev and Yordanov 2004). Based on the result, the traditional landraces and tolerant variety (N22) maintained better photosynthesis under drought condition compared to the susceptible (IR64) variety. However, more significantly, the traditional landraces such as Kalajeera, Machhakanta and Haldichudi showed better photosynthetic rate and photochemical efficiency of PSII than that of tolerant check variety (N22) and showed a more adaptive response to drought.

The studied traditional rice landraces and tolerant variety (N22) maintained higher RWC and MSI than the susceptible variety under different levels of drought stress and showed a more adaptive response to drought (Fig. 2a, b). Our results are consistent with the previous findings that leaf RWC and MSI are important physiological index widely used for the evaluation of water stress tolerance in rice (Rebolledo et al. 2012; Soleymani and Shahrajabian 2012; Swapna and Shyalaraj 2017; Bhattacharjee and Dey 2018). In addition, lipid peroxidation is considered as an indicator of oxidative stress and MDA is considered as a lipid peroxidation biomarker (Panda 2007). In the present study, when the rice seedlings are subjected to drought treatments, MDA levels prominently increased (Fig. 2c). The increased MDA content suggests that drought stress damaged the cell membrane which disturbs metabolic processes and finally inhibits the growth and physiological processes as reported in different rice seedlings (Panda 2007; Wang et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2010). This effect was also evidenced in the present findings by the decrease in photosynthetic pigments in rice seedlings under drought. The low level of oxidative damage in traditional landraces under different drought treatment suggests the potentiality of traditional rice lines for oxidative protection under drought stress (Basu et al. 2010; Kumar et al. 2011; Singh et al. 2013).

For genetic diversity study, SSR markers have the remarkable potential to discriminate between rice genotypes compared to other molecular markers (Anupam et al. 2017). In this study, different drought-linked SSR markers generated about 2.2 alleles per locus, indicating a low level of diversity among the studied genotypes. The level of polymorphism is low since only drought responsive markers were used in the study. The highest Nei’s gene diversity is only 0.719 for RM324, RM515 and RM72, which generated the maximum four bands while most of the SSR markers amplified two bands (Table 3). Diversity based on drought QTL’s varies within genotypes and is also influenced by environments (Anupam et al. 2017). The low level of genetic diversity obtained among the genotypes might be due to the similar origin, ecotype and speciation as traditional genotypes were collected only from, Koraput. Shannon’s information Index (I) is the measure of the heterozygosity of the SSR markers more precisely (Goswami et al. 2017). Among the studied 19 SSR markers, RM324, RM515 and RM72 showed the highest number of effective alleles with the highest value of I in the studied genotypes. Whereas, RM315, RM19367, RM344 and RM321 showed I value as zero due to the abundance of only one type of allele (Table 3). These showed lower heterozygosity and these markers are not potent enough to characterize the studied rice genotypes for drought tolerance. The polymorphism rate of a marker at a specific locus are distinguishable using markers that have PIC values of 0.5 or higher (Anupam et al. 2017). Based on the result, seven SSR loci, RM324, RM19367, RM72, RM246, RM3549, RM566 and RM515 showed the higher PIC values and are potential for exploring the genetic diversity of rice genotypes for drought tolerance (Karmakar et al. 2012).

Characterizing genotypes for drought tolerance among indigenous rice landraces were carried out by cluster analysis using the presence or absence of particular bands. Further, these parameters were compared with drought tolerant (N22) and susceptible (IR64) variety. The information on genetic distance among the landraces could be useful for selection of donor in rice breeding program (Anupam et al. 2017). Based on the pair-wise genetic similarity analysis it is revealed that two indigenous landraces, such as Pandkagura and Mugudi showed the highest genetic similarity with drought-tolerant check variety (N22). The genetic response of Dandarbayagundar landraces was more closure to drought susceptible check variety (IR64). However, most significantly three rice landraces including Kalajeera, Haldichudi and Machhakanta are more diverse and showed higher genetic distance with drought-tolerant check variety (N22). These three highly genetic divergence landraces can be the best choice in drought breeding program. This genotypic response also proved by cluster analysis as Kalajeera, Haldichudi and Machhakanta formed two distinct sub-clusters and separated from tolerant check variety (N22).

Conclusion

Physiological profiling for drought tolerance indicated that all the six indigenous rice landraces possess drought tolerant properties with varying potentiality. However, three landraces (Kalajeera, Machhakanta and Haldichudi) showed the highest degree of tolerance to drought stress compared to tolerant check variety (N22). The more adaptive response to drought of these landraces seems to be associated with better photosynthetic rate and better photochemical efficiency of PSII along with maintenance of higher leaf relative water content under drought condition. Similarly, based on the molecular genotyping analysis, three rice landraces (Kalajeera, Haldichudi and Machhakanta) found to be more diverse and showed the highest genetic distance than the drought-tolerant check variety (N22). These landraces can be considered as the potential donor for drought breeding program and the molecular markers can be used for marker-assisted breeding work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Science and Technology Department, Govt. of Odisha [Ref. No. 3340 (Sanc.)/ST/22.06.17] for financial support and University Grants Commission, New Delhi, Govt. of India for providing Non-NET Fellowship. The authors are grateful to Head, Department of Biodiversity and Conservation of Natural Resources for providing necessary facilities for the work. The Regional Director, MS Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF), Jeypore, Odisha and the Director, National Rice Research Institute, Cuttack, Odisha are highly acknowledged for providing the rice seeds for the experiment.

Author contributions

SSM and DP designed the experiments, cultivated the plants. SSM and PB performed the measurement of physiological traits. VK and SKL performed the molecular analysis. DP analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors read and provided helpful discussions for the manuscript.

References

- Abenavoli MR, Leone M, Sunseri F, Bacchi M, Sorgona A. Root phenotyping for drought tolerance in bean landraces from Calabria (Italy) J Agron Crop Sci. 2016;202:1–2. doi: 10.1111/jac.12124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov N, Tai S, Wang W, Mansueto L, Palis K, Fuentes RR, Ulat VJ, Chebotarov D, Zhang G, Li Z, Mauleon R. SNP-Seek database of SNPs derived from 3000 rice genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43(D1):D1023–D1027. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anower MR, Boe A, Auger D, Mott IW, Peel MD, Xu L, Kanchupati P, Wu Y. Comparative drought response in eleven diverse alfalfa accessions. J Agron Crop Sci. 2017;203(1):1–3. doi: 10.1111/jac.12156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anupam A, Imam J, Quatadah SM, Siddaiah A, Das SP, Variar M, Mandal NP. Genetic diversity analysis of rice germplasm in Tripura State of Northeast India using drought and blast linked markers. Rice Sci. 2017;24(1):10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rsci.2016.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam V, Chaudhury SS, Sarangi SK, Ray T, Mohanty BP, Nambi VA, Mishra S (2006) Rising on rice: the story of Jeypore. Chennai: MS Swaminathan Research Foundation 1:39

- Atkinson NJ, Urwin PE. The interaction of plant biotic and abiotic stresses: from genes to the field. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(10):3523–3543. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Roychoudhury A, Saha PP, Sengupta DN. Comparative analysis of some biochemical responses of three indica rice varieties during polyethylene glycol-mediated water stress exhibits distinct varietal differences. Acta Physiol Plant. 2010;32(3):551–563. doi: 10.1007/s11738-009-0432-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier J, Kumar A, Ramaiah V, Spaner D, Atlin G. A large-effect QTL for grain yield under reproductive-stage drought stress in upland rice. Crop Sci. 2007;47(2):507–516. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2006.07.0495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S, Dey N. Redox metabolic and molecular parameters for screening drought tolerant indigenous aromatic rice cultivars. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2018;24(1):7–23. doi: 10.1007/s12298-017-0484-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga GG, Becker V, Oliveira JN, Mendonça Junior JR, Bezerra AF, Torres LM, Galvão ÂM, Mattos A. Influence of extended drought on water quality in tropical reservoirs in a semiarid region. Acta Limnol Bras. 2015;27(1):15–23. doi: 10.1590/S2179-975X2214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calatayud A, Roca D, Martínez PF. Spatial-temporal variations in rose leaves under water stress conditions studied by chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2006;44(10):564–573. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centritto M, Lauteri M, Monteverdi MC, Serraj R. Leaf gas exchange, carbon isotope discrimination, and grain yield in contrasting rice genotypes subjected to water deficits during the reproductive stage. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(8):2325–2339. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutia J, Borah SP. Water stress effects on leaf growth and chlorophyll content but not the grain yield in traditional rice (Oryza sativa Linn.) genotypes of Assam, India II. Protein and proline status in seedlings under PEG induced water stress. Am. J Plant Sci. 2012;3(07):971–982. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2012.37115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit S, Swamy BM, Vikram P, Ahmed HU, Cruz MS, Amante M, Atri D, Leung H, Kumar A. Fine mapping of QTLs for rice grain yield under drought reveals sub-QTLs conferring a response to variable drought severities. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125(1):155–169. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1823-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit S, Singh A, Cruz MT, Maturan PT, Amante M, Kumar A. Multiple major QTL lead to stable yield performance of rice cultivars across varying drought intensities. BMC Genet. 2014;15(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-15-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq M, Kobayashi N, Wahid A, Ito O, Basra SMA. Strategies for producing more rice with less water. Adv Agron. 2009;101:351–388. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(08)00811-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthami P, Subrahmanyam D, Padma V, Kiran TV, Rao YV, Rao PR, Voleti SR. Variation in leaf photosynthetic response of rice genotypes to post-anthesis water deficit. Ind J Plant Physiol. 2014;19(2):127–137. doi: 10.1007/s40502-014-0086-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire KH, Quiatchon LA, Vikram P, Swamy BM, Dixit S, Ahmed H, Hernandez JE, Borromeo TH, Kumar A. Identification and mapping of a QTL (qDTY1. 1) with a consistent effect on grain yield under drought. Field Crops Res. 2012;131:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2012.02.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami S, Kar RK, Paul A, Dey N. Genetic potentiality of indigenous rice genotypes from Eastern India with reference to submergence tolerance and deepwater traits. Curr Plant Biol. 2017;11:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cpb.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125(1):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang TY, Sayama TA, Takahashi MA, Takada YO, Nakamoto YU, Funatsuki HI, Hisano HI, Sasamoto SH, Sato SH, Tabata SA, Kono IZ. High-density integrated linkage map based on SSR markers in soybean. DNA Res. 2009;16(4):213–225. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail AM, Johnson DE, Ella ES, Vergara GV, Baltazar AM. Adaptation to flooding during emergence and seedling growth in rice and weeds, and implications for crop establishment. AoB Plants. 2012 doi: 10.1093/aobpla/pls019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Escuredo PR, Arrese-Igor C, Becana M. Oxidative damage in pea plants exposed to water deficit or paraquat. Plant Physiol. 1998;116(1):173–181. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.1.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoshita A, Babu RC, Boopathi NM, Fukai S. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of drought-resistance traits for development of rice cultivars adapted to rainfed environments. Field Crops Res. 2008;109(1–3):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2008.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar J, Roychowdhury R, Kar RK, Deb D, Dey N. Profiling of selected indigenous rice (Oryza sativa L.) landraces of Rarh Bengal in relation to osmotic stress tolerance. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2012;18(2):125–132. doi: 10.1007/s12298-012-0110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Michniewicz M, Bergmann DC, Wang ZY. Brassinosteroid regulates stomatal development by GSK3-mediated inhibition of a MAPK pathway. Nature. 2012;482(7385):419–422. doi: 10.1038/nature10794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Crow JF. The number of alleles that can be maintained in a finite population. Genetics. 1964;49(4):725–738. doi: 10.1093/genetics/49.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar RR, Karajol K, Naik GR. Effect of polyethylene glycol induced water stress on physiological and biochemical responses in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L. Millsp.). Recent Res. Sci Technol. 2011;3(1):148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lang NT, Nha CT, Ha PT, Buu BC. Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) associated with drought tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Sabrao J Breed Genet. 2013;45(3):409–421. [Google Scholar]

- Lenka SK, Katiyar A, Chinnusamy V, Bansal KC. Comparative analysis of drought-responsive transcriptome in Indica rice genotypes with contrasting drought tolerance. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9(3):315–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin R. C. Evolutionary Biology. New York, NY: Springer US; 1972. The Apportionment of Human Diversity; pp. 381–398. [Google Scholar]

- Mafakheri A, Siosemardeh A, Bahramnejad B, Struik PC, Sohrabi Y. Effect of drought stress on yield, proline and chlorophyll contents in three chickpea cultivars. Aust J Crop Sci. 2010;4(8):580–585. [Google Scholar]

- Makbul S, Güler NS, Durmuş N, Güven S. Changes in anatomical and physiological parameters of soybean under drought stress. Turkish J Bot. 2011;35(4):369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Mathobo R, Marais D, Steyn JM. The effect of drought stress on yield, leaf gaseous exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of dry beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Agricul Water Manag. 2017;180:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2016.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell K, Johnson GN. Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide. J Exp Bot. 2000;51(345):659–668. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.345.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCouch S, Baute GJ, Bradeen J, Bramel P, Bretting PK, Buckler E, Burke JM, Charest D, Cloutier S, Cole G, Dempewolf H. Agriculture: feeding the future. Nature. 2013;499(7456):23–24. doi: 10.1038/499023a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra SS, Panda D (2017a) Characterisation of folk rice varieties from Koraput for drought stress tolerance: valuing agro-ecology and food security. In Agriculture and human development in India: Indigenous practices, scientific views and sustainability. International conference, IIT Guwahati

- Mishra SS, Panda D. Leaf traits and antioxidant defense for drought tolerance during early growth stage in some popular traditional rice landraces from Koraput, India. Rice Sci. 2017;24(4):207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.rsci.2017.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra KK, Vikram P, Yadaw RB, Swamy BM, Dixit S, Cruz MT, Maturan P, Marker S, Kumar A. qDTY 12.1: a locus with a consistent effect on grain yield under drought in rice. BMC Genet. 2013;14(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Thompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8(19):4321–4326. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1973;70(12):3321–3323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.12.3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaud O, Chen X, McCouch SR. Development of microsatellite markers and characterization of simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252(5):597–607. doi: 10.1007/BF02172406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda SK. Chromium-mediated oxidative stress and ultrastructural changes in root cells of developing rice seedlings. J Plant Physiol. 2007;164(11):1419–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey V, Shukla A. Acclimation and tolerance strategies of rice under drought stress. Rice Sci. 2015;22(4):147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.rsci.2015.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S, Bhandari H, Ding S, Prapertchob P, Sharan R, Naik D, Taunk SK, Sastri A. Coping with drought in rice farming in Asia: insights from a cross-country comparative study. Agric Econ. 2007;37(s1):213–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2007.00246.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patra BC, Dhua SR. Agro-morphological diversity scenario in upland rice germplasm of Jeypore tract. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2003;50(8):825–828. doi: 10.1023/A:1025963411919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Mu P, Zhang H, Chen CY, Gao Y, Tian Y, Wen F, Li Z. Mapping QTLs of root morphological traits at different growth stages in rice. Genetica. 2008;133(2):187–200. doi: 10.1007/s10709-007-9199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman ANMRB, Zhang J. Flood and drought tolerance in rice: opposite but may coexist. Food Energy Secur. 2016;5(2):76–88. doi: 10.1002/fes3.79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchander S, Raveendran M, Robin S. Mapping QTLs for physiological traits associated with drought tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) J Investig Genom. 2016;3(3):00052. [Google Scholar]

- Rebolledo MC, Dingkuhn M, Clément-Vidal A, Rouan L, Luquet D. Phenomics of rice early vigour and drought response: Are sugar related and morphogenetic traits relevant? Rice. 2012;5(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1939-8433-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy PS, Patnaik A, Rao GJ, Patnaik SS, Chaudhury SS, Sharma SG. Participatory and molecular marker assisted pure line selection for refinement of three premium rice landraces of Koraput, India. Agroeco Sus Food Syst. 2017;41(2):167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sairam RK. Effect of moisture-stress on physiological activities of two contrasting wheat genotypes. Ind J Exp Biol. 1994;32:594–597. [Google Scholar]

- Samal R, Roy PS, Sahoo A, Kar MK, Patra BC, Marndi BC, Gundimeda JN. Morphological and molecular dissection of wild rices from eastern India suggests distinct speciation between O. rufipogon and O. nivara populations. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2773. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20693-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu N, Singh A, Dixit S, Cruz MT, Maturan PC, Jain RK, Kumar A. Identification and mapping of stable QTL with main and epistasis effect on rice grain yield under upland drought stress. BMC Genet. 2014;15(1):63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-15-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar RK, Bhattacharjee B. Rice genotypes with SUB1 QTL differ in submergence tolerance, elongation ability during submergence and re-generation growth at re-emergence. Rice. 2011;5(1):7. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsudin NA, Swamy BM, Ratnam W, Cruz MT, Raman A, Kumar A. Marker assisted pyramiding of drought yield QTLs into a popular Malaysian rice cultivar, MR219. BMC Genet. 2016;17(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s12863-016-0334-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Sengar K, Sengar RS. Gene regulation and biotechnology of drought tolerance in rice. Int J Biotechnol Bioeng Res. 2013;4(6):547–552. [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Singh Y, Xalaxo S, Verulkar S, Yadav N, Singh S, Singh N, Prasad KS, Kondayya K, Rao PR, Rani MG. From QTL to variety-harnessing the benefits of QTLs for drought, flood and salt tolerance in mega rice varieties of India through a multi-institutional network. Plant Sci. 2016;242:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleymani A, Shahrajabian MH. Study of cold stress on the germination and seedling stage and determination of recovery in rice varieties. Int J Biol. 2012;4(4):23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stirbet A, Govindjee On the relation between the Kautsky effect (chlorophyll a fluorescence induction) and photosystem II: basics and applications of the OJIP fluorescence transient. J Photochem Photobiol. 2011;104(1–2):236–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser RJ, Tsimilli-Michael M, Srivastava A (2004) Analysis of the chlorophyll a fluorescence transient. In: Papageorgiou GC, Govindjee (eds.) Chlorophyll a fluorescence: a signature of photosynthesis. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 321–362

- Swamy BPM, Ahmed HU, Henry A, et al. Genetic, physiological, and gene expression analyses reveal that multiple QTL enhance yield of rice mega-variety IR64 under drought. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e62795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swapna S, Shyalaraj KS. Screening for osmotic stress responses in rice varieties (Oryza sativa L.) under drought condition. Rice Sci. 2017;24(5):253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.rsci.2017.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talebi R. Evaluation of chlorophyll content and canopy temperature as indicators for drought tolerance in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Aust J Basic App Sci. 2011;5(11):1457–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Todaka D, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Recent advances in the dissection of drought-stress regulatory networks and strategies for development of drought-tolerant transgenic rice plants. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:84. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venuprasad R, Dalid CO, Del Valle M, Zhao D, Espiritu M, Cruz MS, Amante M, Kumar A, Atlin GN. Identification and characterization of large-effect quantitative trait loci for grain yield under lowland drought stress in rice using bulk-segregant analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;120(1):177–190. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venuprasad R, Bool ME, Quiatchon L, Cruz MS, Amante M, Atlin GN. A large-effect QTL for rice grain yield under upland drought stress on chromosome 1. Mol Breed. 2012;30(1):535–547. doi: 10.1007/s11032-011-9642-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vikram P, Swamy BM, Dixit S, Ahmed HU, Cruz MT, Singh AK, Kumar A. qDTY 1.1, a major QTL for rice grain yield under reproductive-stage drought stress with a consistent effect in multiple elite genetic backgrounds. BMC Genet. 2011;12(1):89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-12-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikram P, Kadam S, Singh BP, Pal JK, Singh S, Singh ON, Swamy BM, Thiyagarajan K, Singh S, Singh NK. Genetic diversity analysis reveals importance of green revolution gene (Sd1 Locus) for drought tolerance in rice. Agric Res. 2016;5(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40003-015-0199-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZJ, Chen YJ, Xie CH, Yang GT. Effect of water stress on photosynthesis and yield character of hybrid rice at different stages. Agric Res Arid Areas. 2008;26:138–142. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh FC, Boyle TJB. Population genetic analysis of co-dominant and dominant markers and quantitative traits. Belgian J Bot. 1997;129:157. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S (1976) Routine procedure for growing rice plants in culture solution. Laboratory manual for physiological studies of rice, pp 61–66

- Zhang H, Liu W, Wan L, Li F, Dai L, Li D, Zhang Z, Huang R. Functional analyses of ethylene response factor JERF3 with the aim of improving tolerance to drought and osmotic stress in transgenic rice. Transgen Res. 2010;19(5):809–818. doi: 10.1007/s11248-009-9357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Yu S, Zuo K, Luo L, Tang K. Identification of gene modules associated with drought response in rice by network-based analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlatev ZS, Yordanov IT. Effects of soil drought on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence in bean plants. Bulg J Plant Physiol. 2004;30(3–4):3–18. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.