Abstract

Objective:

Clinicians treating the increasing numbers of bipolar elders with mood stabilizers need evidence from age-specific randomized controlled trials. We describe findings from a first such study of late-life mania.

Method:

We compared the tolerability and efficacy of lithium carbonate and divalproex in 224 inpatients and outpatients aged ≥ 60 years with bipolar disorder (BD) type I, presenting with a manic, hypomanic or mixed episode. Participants were randomized under double-blind conditions to target serum concentrations of lithium (0.80–0.99 mEq/L) or valproate (80–99 mcg/ml) for 9 weeks. Participants with inadequate response after 3 weeks received open adjunctive risperidone. We hypothesized that divalproex would be better tolerated and more efficacious than lithium. Tolerability was assessed based on a measure of sedation and on the proportion achieving target concentrations. Efficacy was assessed with the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS).

Results:

Attrition rates were similar for lithium and divalproex (14% and 18% at week 3, and 51% and 44% at week 9, respectively). The groups did not differ statistically either in terms of sedation. Those randomized to lithium tended to experience more tremor. A similar proportion of participants achieved target concentrations (57% and 56%). A longitudinal mixed-model of improvement (YMRS change from baseline) favored lithium (3.90; CI: 1.71 – 6.09). Nine week response rates did not differ (79% and 73%). The need for adjunctive risperidone was low and similar (17% and 14%).

Conclusion:

Both lithium and divalproex were adequately tolerated and efficacious; lithium was associated with a greater reduction in mania scores over 9 weeks.

INTRODUCTION

In late-life, bipolar disorder (BD) is associated with high utilization of mental health and other medical services (1), persisting disability (2), increased mortality (3), and increased risk for suicide (4) and dementia (5). Despite the increasing number of older adults with bipolar disorder, evidence that can guide their treatment is strikingly limited. Physiological changes and comorbid diseases increase their vulnerability to adverse effects of medication (6, 7). The sparse literature on treatment outcomes for late-life mania is inconsistent (6, 8–10).

Both lithium and divalproex are approved by the FDA for the treatment of bipolar disorder (11) and they are the traditional mood stabilizers most commonly prescribed to older patients Although some analyses of geriatric patients in open studies have been published, most information to guide their use has been extrapolated from younger adults with bipolar disorder or retrospective analyses of a limited number of older patients (12). Lithium has the strongest evidence supporting both its acute and long-term efficacy in midlife adults with bipolar disorder. Uncontrolled data suggest that lithium can also be efficacious in bipolar disorder in late life (12) for which it remains commonly prescribed despite some decline in new prescriptions (13). However, many older patients do not tolerate lithium concentrations recommended for younger patients (14) and concerns over its tolerability lead to use of either unproven lower concentrations (15) or alternative medications such as divalproex.

Divalproex is reportedly well tolerated by non-demented elders, including patients with neurological and medical disorders. Case series suggest that it can be effective for the treatment of late-life mania (12). Its use in older patients has been increasing (13) despite the absence of randomized controlled trials comparing its tolerability and efficacy to that of lithium or other agents in this population. Our review of open treatment data in older patients (12) and related literature in younger patients (11) suggested more sedation with divalproex than with lithium, but less tremor and other side effects.

Optimal serum concentrations of lithium or valproate for treatment of older patients with bipolar disorder are not established, and open treatment has involved a range of concentrations. In elders, tolerability can limit dosing and thereby efficacy. Our review (12) indicated that relatively low concentrations of lithium (0.30–0.79 mEq/L) may be less effective than higher concentrations (0.80 mEq/L) or than usual therapeutic levels of valproate (72–84 mcg/ml) (15). Nonetheless, in one case series, geriatric mania was treated successfully with lithium levels of (0.5–0.8 mEq/L) (16). Thus, the relative tolerability and efficacy of lithium and divalproex remain unknown in older patients treated with these mood stabilizers.

We therefore conducted a randomized, double blind, concentration-controlled study to compare the acute tolerability and efficacy of lithium and divalproex in older adults with bipolar disorderI presenting with mania. Based on the existing literature, we hypothesized that patients treated with divalproex would experience greater sedation, but expected that patients treated with lithium would experience more tremor and other adverse effects (14). Thus, we expected that divalproex would be better tolerated overall and hypothesized that a higher proportion of patients treated with divalproex would achieve a potentially beneficial target concentration. As a result, we predicted that divalproex would be more efficacious than lithium.

METHOD

Design Overview

We conducted a nine-week randomized, double-blind, parallel group trial. Participants were elders with type bipolar disorderI presenting with mania or hypomania. Dosing was guided by drug concentration. Participants with inadequate response after three weeks received open, adjunctive treatment with risperidone.

Setting and Participants

We recruited participants at six academic centers, from both inpatient and ambulatory services. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants as required by the local Institutional Review Boards: mental health professionals who were not part of the research team assessed and documented the participants’ capacity to provide written informed consent. When potential participants did not have capacity, consent was provided by a substitute decision-maker.

The inclusion criteria specified: age ≧ 60 years; meeting DSM IV criteria for bipolar disorder type I with a current manic, mixed, or hypomanic episode (17) based on the SCID (18); and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)(19) score ≧ 18. Patients were excluded if they had: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder(17); contraindication to lithium or divalproex; a history of intolerance of lithium (at a concentration < 1.0 mEq/L) or divalproex (with a valproate concentration < 100 mcg/ml), lorazepam, or risperidone; failure of current episode to respond to at least 4 weeks of treatment with lithium (≥ 0.4 mEq/L) or divalproex (valproate ≥ 40 mcg/ml); active substance dependence or other substance-related safety issues; a mood disorder due to a general medical condition (e.g., recent stroke, hyperthyroidism, porphyria, HIV infection, connective tissue diseases) or a substance (e.g., steroids, L-DOPA); rapid cycling; a diagnosis of delirium or dementia or other brain degenerative diseases; inability to communicate in English; sensory impairment preventing participation in research assessments; unstable medical condition; high risk for suicide (in ambulatory patients); and requirement for other immediate pharmacological intervention.

Assessments

Antidepressants and other non-study medications were tapered off to ascertain whether manic symptoms would resolve with their discontinuation. Baseline assessments included demographic information, YMRS ratings, and the SCID (18), Montgomery Asberg Depression Ratings Scale (MADRS)(20), the UKU Side Effect Scale (21), a physical and laboratory examinations.

Randomization

Eligible patients were randomized under double-blind conditions on a 1:1 basis to lithium or divalproex. Permuted block randomization employed block sizes ranging randomly from 4 to 8 consecutive patients by site. Participants received monotherapy with lithium or divalproex in over-encapsulated pills given twice daily.

Intervention

The starting dose was 300 mg/day for lithium and 500 mg/day for divalproex. The dose was titrated to achieve the following target concentrations: (1) lithium target range: 0.80–0.99 mEq/L; acceptable range: 0.40–0.99 mEq/L; (2) valproate target range: 80–99 mcg/ml; acceptable range: 40–99 mcg/ml. Trough concentrations were determined 10–14 hours after the last dose on treatment days 4, 9, 15 and 21, at weeks 6 and 9, and more frequently if indicated. Concentrations were reported to a non-blind clinician who created an equivalent “dummy concentration” for the other drug (e.g., 0.58 mEq/L and 58 mcg/ml); both concentrations were then provided to the blinded psychiatrist. Titration to the target ranges was carried out regardless of mood improvement. Dosing was reduced if serum concentrations exceeded the target range, significant side effects occurred (including tremor interfering with self-care, ataxic gait, excessive sedation, heart rate < 50) or if the blinded research psychiatrist had other concerns. The research medication was discontinued, and the participant terminated the study if these side effects persisted despite a dose reduction or if the following occurred and persisted: inability to tolerate at least 0.40 mEq/L of lithium or 40 mcg/ml of valproate; delirium; platelet count below 80,000; elevation in SGOT, SGPT, or amylase, two fold or higher above the upper limit of normal; or diabetes insipidus.

Standard behavioral interventions were used for all participants including provision of an educational brochure (22); reduction of excess social stimuli; or use of seclusion and restraint for inpatients if needed for safety. During the first three weeks of treatment, lorazepam was used at a maximum dose of 3 mg/day when anxiety, agitation or insomnia was significant and not responsive to behavioral interventions. In participants who did not respond to behavioral intervention and lorazepam, oral risperidone (23) rescue 0.5–1 mg was used up to twice a day and for up to three days in any week. Participants who required more than these doses terminated the study. After three weeks of treatment, risperidone up to 4 mg/day was used for an inadequate response to lithium or divalproex, defined as YMRS ≥ 16, and lorazepam was tapered off. Patients not receiving adjunct risperidone could receive lorazepam 0.5–1.0 mg/day for persistent anxiety or insomnia.

Other psychotropics were not allowed but medications for comorbid physical conditions were continued. When non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents or thiazide diuretics were required, mood stabilizer dosages were adjusted based on serum concentrations.

Participants could also terminate the study due to withdrawal of consent; a serious adverse event; increase in YMRS score > 40 % above baseline; development of major depression with 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (24) scores ≥ 18 on two successive assessments or requirement for antidepressant treatment; clinician recommendation; or non-adherence to study procedures and medications.

Conduct of the study was monitored by an Operations Committee and by an NIMH Data Safety Monitoring Board. Data management was performed at Weill Cornell.

Statistical Analysis of Tolerability and Efficacy

The primary clinical tolerability measure was the UKU Sleepiness/Sedation item; the primary pharmacologic tolerability measure was the proportion achieving concentrations within the target range; and the primary efficacy measure was the change in YMRS scores. The analysis for primary outcomes was based on intent-to-treat (ITT) with a generalized linear mixed model for continuous and binary or multinomial longitudinal response. A patient-level random intercept was assumed, and linear (time) and time x treatment factors were included in the model. Higher polynomial orders of the time term (quadratic (time2), cubic (time3) or quartic (time4)) and their corresponding interactions with treatment were explored and retained in the model based on best model fit and visual inspection of observed and predicted values. Site was included as a covariate in the model. In addition, site x time and site x time x treatment interactions were investigated and included if they were significant and improved model fit. Individual UKU item scores (range: 0–3) were analyzed as both continuous and ordinal outcomes in linear and ordinal logistic mixed model respectively; conclusions were similar, and results from the continuous outcome analysis are presented. A binary UKU outcome was also defined as an increase of 2 points from baseline or reaching 3; it was analyzed in a generalized linear mixed model; conclusions were similar to continuous UKU scores except for tremor, which had few events and did not converge.

Post-hoc tests for treatment comparisons were conducted for each outcome on the chosen mixed model to test group difference at weeks 3 and 9. Corresponding estimates of treatment difference, standardized effect size (Cohen’s d), confidence intervals, and p-values are also reported. To control for Type I errors due to multiple comparisons, the p-value corresponding to the F-test of the highest interaction term in a mixed model was adjusted using Holm’s step-down procedure for controlling family-wise error rate. Alphas were adjusted using Holm’s procedure and 97.5% confidence intervals (2-tailed) were constructed for the two post-hoc tests for each outcome. The effect size (Cohen’s d) for treatment difference was based on the mixed model estimated least-square means and standard deviations (raw) at weeks 3 and 9.

To explore whether differences in treatment outcomes between groups were associated with whether or not concurrent serum concentrations were at target, a linear mixed model as described above was used with additional fixed effects for target, target x time, target x treatment and target x time x treatment.

Using similar linear mixed models, two treatment moderators (older age and mixed-manic state) were tested using additional fixed effects for moderator, moderator x time, moderator x treatment and moderator x time x treatment interaction. A significant three-way interaction would indicate the effect of a moderator.

Using a two-tailed 2.5% level of significance for the primary hypotheses, we calculated a priori that a sample size of 207 would provide 82% power for minimal differences of 20%, i.e., a difference of 20% in the rates of sedation or treatment response for the tolerability and efficacy hypotheses, respectively. This estimate of power was conservative as multiple visits per patient were not taken into consideration due to lack of within-subject correlation information.

RESULTS

Participants

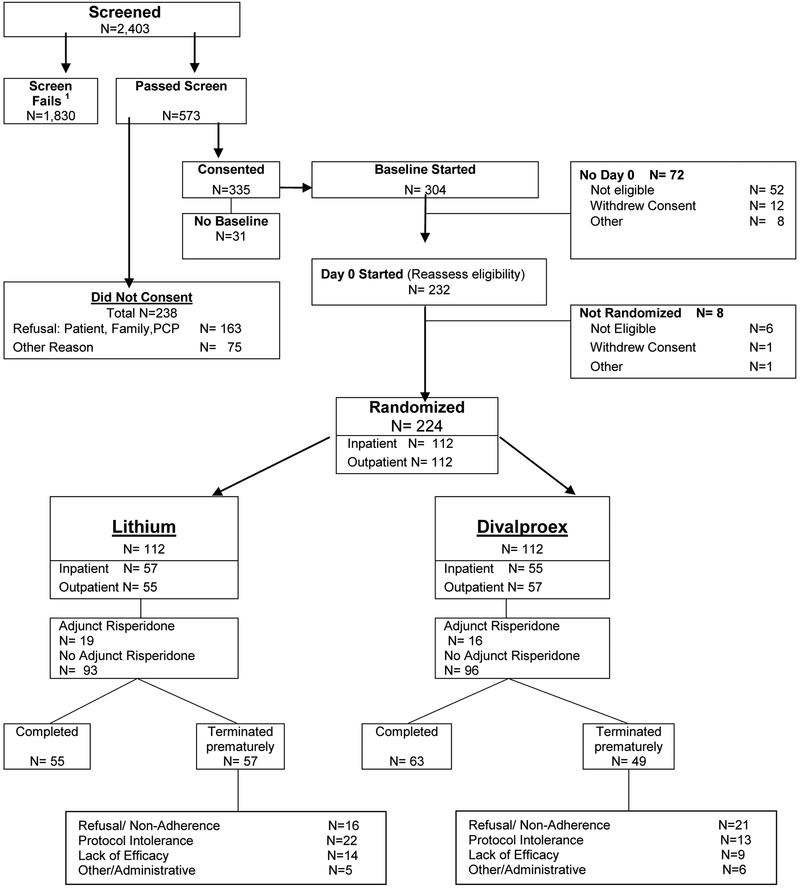

The flow of subjects is outlined in Figure 1. The most frequent reasons for exclusion from the study were a low YMRS score or the presence of a major depressive episode. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 224 randomized participants did not differ between the two treatment groups (Table 1). Age at onset of first manic episode ranged from 9 to 82 yrs.

Figure 1. CONSORT Chart.

TABLE 1:

Characteristics of Geri-BD Randomized Sample

| Full Sample | Lithium | Divalproex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 224 | 100% | 112 | 50% | 112 | 50% |

| Age (yrs) | 68.0 (6.4) | 67.6 (6.8) | 68.3 (6.1) | |||

|

Gender: Male Female |

115 109 |

51% 49% |

56 56 |

50% 50% |

59 53 |

53% 47% |

| Education (yrs) | 13.4 (3.1) | 13.1 (2.8) | 13.7 (3.4) | |||

|

Race: Caucasian African-American Asian |

194 26 4 |

87% 11% 2% |

97 14 1 |

87% 13% 1% |

97 12 3 |

87% 11% 2% |

|

Ethnicity:

Hispanic Non-Hispanic |

15 109 |

7% 93% |

8 104 |

7% 93% |

7 105 |

6% 94% |

|

Marital Status:

Never Married Married Separated, Widowed, Div. |

22 81 121 |

10% 36% 54% |

12 47 52 |

11% 42% 47% |

10 34 68 |

9% 30% 61% |

|

Recruitment Setting: Inpatient Outpatient |

112 112 |

50% 50% |

57 55 |

51% 49% |

55 57 |

49% 51% |

|

Mood State:

Manic Mixed Hypomanic Psychotic |

144 52 28 74 |

64.3% 23.2% 12.5% 34% |

76 28 8 40 |

68% 25% 7% 37% |

68 24 20 34 |

61% 21% 18% 31% |

| Onset of First Manic Episode (yrs) | 39.6 (20.0) | 40.6 (20.3) | 38.8 (20.0) | |||

|

Prior Treatment of Current Episode

With a Mood Stabilizer |

90 | 42% | 43 | 39% | 47 | 44% |

| Sedation/Sleepiness UKU | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.6) | |||

| YMRS | 26.3 (6.8) | 27.1 (7.4) | 25.5 (6.1) | |||

| CIRS-G | 8.3 (3.8) | 8.3 (3.8) | 8.3 (3.7) |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean (S.D.). Rating scale scores are at baseline.

Overall Attrition

The attrition rates in the lithium and divalproex groups were 14% and 18 %, respectively, at week 3 (χ2(1) =0.52, p = 0.47) and 51% and 44% at week 9 (χ2(1)=1.15, p = 0.28). In a longitudinal generalized linear mixed effects model of attrition, the slope did not differ between treatment groups (F1,2238 = 1.33, p = 0.25). Time to attrition was also not statistically different between the treatment groups based on a log-rank test (χ2(1) = 0.90, p = 0.34) of survival curves (Suppl. Fig A). The reasons for attrition did not differ between groups: refusal/non-adherence (lithium: 28.1% vs. divalproex: 42.9%; χ2(1) = 2.54, p = 0.11), inability to tolerate protocol (38.6% vs. 26.5%; χ2(1) = 1.74, p = 0.19), clinical worsening/lack of efficacy (24.6% vs 18.4% (χ2(1) = 0.60, p =0.44), and administrative/other (8.8% vs X 12.2%; χ2(1) = 0.34, p = 0.559) (Figure 1).

In exploratory analyses, rates of 9 week study completion did not differ between treatment groups based on age (age x treatment: χ2(1)=0.58, p=0.45) or medical burden measured by Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatric (CIRSG) (CIRSG x treatment: χ2(1) = 0.001, p = 0.98) when analyzed in two separate logistic regression models with 9-week study completion as outcome.

Rescue and Adjunct Medications

The odds of needing rescue lorazepam or risperidone did not differ statistically between groups (lithium: 60.7% vs. divalproex: 50.9%; OR = 1.49; CI: 0.88–2.5, p = 0.14). Similarly, the use of adjunct risperidone (i.e., consistent use up to 4 mg/day after week 3) did not differ significantly (lithium: 17.0% vs. divalproex: 14.3%; OR = 1.23; CI 0.59–2.5, p = 0.58). However, the two groups differed in the use of daily lorazepam daily after day 28 (lithium: 9.8% vs. divalproex: 19.6%; χ2(1) = 4.3; p = 0.038).

Tolerability

Side Effects Ratings (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Statistical Tests

| Outcome Measure | Post-hoc Test | Model | Test | Estimate* | Unadjusted P-value | Adjusted P-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | YMRS (Change from Baseline) | site, time, time2, treatment and treatment × time | F1,1382 = 16.87 | <0.0001 | <0.0007 | ||

| D-L (3wk) | 1.57 (−0.29, 3.42) | 0.0583 | 0.0583 | ||||

| D-L (9wk) | 3.90 (1.71, 6.09) | <0.0001 | <0.0002 | ||||

| Target Blood Level | site, time, time2, time3, treatment and treatment × time | F1,1116 = 0.24 | 0.6265 | 1 | |||

| D-L (3wk) | 0.20 (−0.96, 1.35) | 0.7029 | 1 | ||||

| D-L (9wk) | −0.07 (−1.38, 1.25) | 0.9106 | 1 | ||||

| Continuous UKU3 (Sleeping/Sedation) | site, time, time2, time3, treatment, treatment × time, treatment × time2 and treatment × time3 | F1,1367 = 3.13 | 0.077 | 0.308 | |||

| D-L (3wk) | 0.09 (−0.07, 0.24) | 0.2049 | 0.4098 | ||||

| D-L (9wk) | 0.04 (−0.19, 0.27) | 0.7015 | 0.7015 | ||||

|

Secondary |

Continuous UKU15 (Tremor) | site, time, time2, treatment and treatment × time | F1,1365 = 6.62 | 0.0102 | 0.051 | ||

| D-L (3wk) | −0.09 (−0.23, 0.05) | 0.1365 | 0.1365 | ||||

| D-L (9wk) | −0.21 (−0.37, −0.04) | 0.0056 | 0.0112 | ||||

| Continuous UKU23 (Nausea/Vomiting) | site, time, treatment and treatment × time | F1,1368 = 0.90 | 0.3439 | 1 | |||

| D-L (3wk) | −0.07 (−0.20, 0.06) | 0.2094 | 0.2094 | ||||

| D-L (9wk) | −0.13 (−0.31,0.05) | 0.1007 | 0.2014 | ||||

| Continuous UKU35 (Weight Gain) | site, time, time2, time3, treatment and treatment × time | F1,1372 = 8.08 | 0.0045 | 0.027 | |||

| D-L (3wk) | 0.09 (−0.10, 0.29) | 0.2773 | 0.362 | ||||

| D-L (9wk) | −0.16 (−0.42, 0.11) | 0.181 | 0.362 | ||||

| MADRS | categorical time, site, treatment and treatment × time | F2,301=0.03 | 0.9733 | 1 | |||

| D-L (3wk) | −0.7692 (−3.31, 1.78) | 0.4964 | 0.9928 |

D - L is difference between treatment groups: Divalproex minus Lithium.

The F-test for the highest interaction term (e.g., time x treatment) or the estimate of treatment difference at week 3 or week 9 with 97·5% CI (adjusted for multiple testing)

P-values for F-tests adjusted for multiple testing (Holm's procedure) of 7 outcomes and p-value for post-hoc estimates adjusted for two tests within each outcome

There was no significant difference between the treatment groups in the primary measure, change in Sleepiness/Sedation. Planned secondary measures were Tremor, Weight Gain, Nausea and Vomiting. For Tremor, the treatment x time interaction was trend-worthy, with divalproex having lower scores than lithium at week 9 (Cohen’s d = −0.30, 95% CI −0.67, 0.06), but not at week 3 (Cohen’s d = −0.17, 95% CI −0.46, 0.12). For Weight Gain, the treatment x time interaction was significant, but since there was no treatment difference at weeks 3 or 9, the clinical significance of that interaction is unclear. For Nausea/Vomiting, the treatment x time interaction did not differ.

Target Concentrations.

The mean (SD) maximum daily doses and concentrations were 780 (315) mg and 0.76 (0.35) mEq/L for lithium and 1,200 (550) mg and 74 (21) mcg/ml for valproate. Similar proportions of participants achieve target concentrations in the two groups. In the ITT linear mixed model at days 4, 9, 15 and weeks 3, 6 and 9, the treatment x time interaction was not significant (F1,1116 = 0.24, p = 0.69) and post hoc tests showed comparable proportions of subjects achieving target concentrations at weeks 3 (lithium: 35.1%; divalproex : 32.6%) or 9 (57.1%; 56.3%).

Efficacy

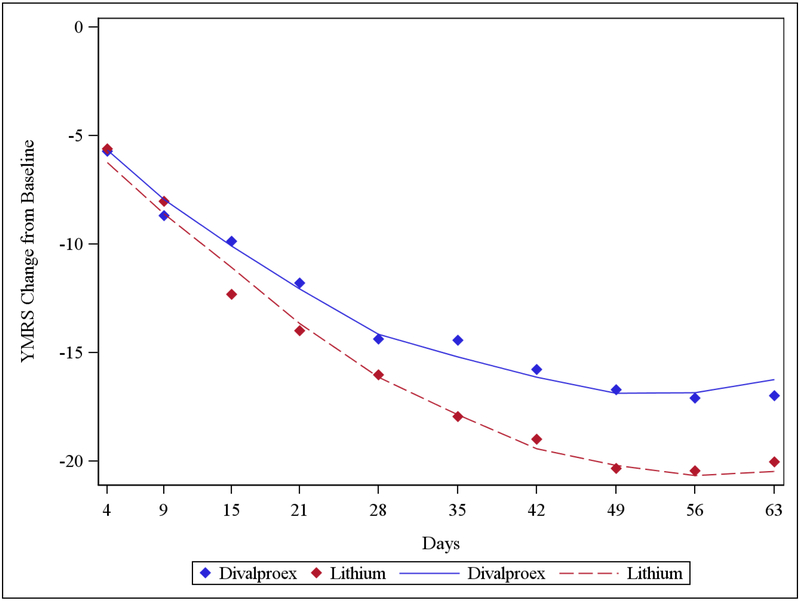

In the ITT linear mixed model of change in YMRS score, there was a significant treatment x time interaction (F1,1382 = 16.87, p < 0.0001). YMRS decreased significantly from baseline in both treatment groups, but the decrease was larger with lithium than divalproex (Figure 2). A post-hoc test showed a difference in YMRS scores of 1.57 (Cohen’s d=0.18, 95% CI: −0.10, 0.47) at week 3 and 3.90 at week 9 (Cohen’s d=0.54, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.91) in favor of lithium. YMRS course over time depended on baseline YMRS: participants with a baseline YMRS > 30 showed a greater reduction on YMRS with lithium than with divalproex (time x treatment x YMRS >30: F3,1379=17.76, p<0.0001), but there was no difference between the effect of lithium or divalproex in participants with baseline YMRS < 30. Among all study participants, the cumulative rates of response (at least 50% reduction of YMRS from baseline) in the lithium and divalproex groups were 62.5% and 57.1% at week 3 (adjusted OR = 0.78, p = 0.37) and 78.6% and 73.2% at week 9 (adjusted OR = 0.72, p = 0.31), respectively; the cumulative rates of remission (YMRS ≤9) were 45.5% and 43.8% at week 3 (adjusted OR = 0.91, p = 0.74) and 69.6% and 63.4% at week 9 (adjusted OR = 0.73, p = 0.29), respectively.

Figure 2. YMRS Change from Baseline.

Solid blue line and dashed red line show the Least Square Means (from mixed models) of YMRS Change from Day 0 for Divalproex and Lithium respectively. Blue and red diamonds represent average YMRS Change from Day 0 at different time points for Divalproex and Lithium respectively.

In an exploratory analysis, the course of YMRS score reduction was different between the two treatment groups based on whether or not concentrations were at target (target x time x treatment interaction: F(1,1379) = 5.80, p = 0.016). Below-target concentrations in the lithium group were associated with the fastest symptomatic reduction (Suppl. Fig. B). In another exploratory analysis, older age (≥ 70 yrs vs. 60–69 yrs) and mixed-manic state (N=52) vs. manic/hypomanic (N=144) did not change the course of treatment effect significantly (age x treatment x time: F(1,1383) = 0.19, p = 0.67 and mixed x treatment x time: F(1,1177) =1.91, p = 0.17).

The MADRS depression scores were analyzed as a secondary efficacy measure; these scores were relatively low at baseline; they decreased during treatment; and there was no significant difference between the groups.

DISCUSSION

This is the first randomized controlled trial of the treatment of late-life mania. Its principal finding is that the overall tolerability and efficacy of lithium and divalproex were comparable in older patients. Contrary to our hypothesis, sedation and the proportion of participants who achieved target concentrations did not differ between the two treatment groups. Overall attrition did not differ significantly between groups and there were no statistical differences in other secondary clinical tolerability measures.

The effect of lithium on ratings of mania severity was statistically larger, with a small effect size at week 3 and a moderate effect size at week 9. The higher use of lorazepam in the divalproex group is consistent with a greater efficacy of lithium. However, rates of response and remission did not differ between the two treatment groups: they were substantial, and less than 20% of participants required an adjunctive antipsychotic, despite the fact that 34% presented with psychotic features and 50% were initially inpatients. Finally, neither mood stabilizer was associated with increased symptoms of depression.

Our findings need to be considered in the context of the literature. First, even though the attrition rates in this study were substantial, they were similar or lower than those in studies of younger patients with mania (25). Second, our findings are consistent with the results of analyses of subgroups of older participants in recent adult studies. The EMBLEM Study reported benefit from mood stabilizers in a geriatric subgroup (10), and in the STEP-BD study lithium monotherapy was associated with remission in 42% in older participants (6). Third, our finding of higher efficacy of lithium than divalproex is congruent with findings of the BALANCE study (26): in remitted mixed-age patients with bipolar disorder assigned randomly to open, continuation treatment with lithium, divalproex, or the combination for up to 24 months, lithium was associated with statistically lower relapse rates, although the effect was small. Finally, we found rates of response or remission similar to the rates reported in younger patients with bipolar disorder treated with lithium or divalproex even though we used lower doses and targeted lower levels. For instance, a three week double-blind randomized controlled trial of lithium and divalproex monotherapy (11) in patients with a mean age of 41 years reported comparable outcomes in the two groups when targeting “conventional” concentrations (i.e., lithium: 0.80–1.20 mEq/L or valproate 80–120 mcg/ml). In younger patients, these concentrations are usually well tolerated and associated with favorable outcomes (27, 28).

The findings concerning primary hypotheses from this study must be interpreted in light of potential limitations. First, although the inclusion criteria were intended to be as broad as safely possible, a relatively large number of patients were excluded. Second, in the absence of a placebo group, it is possible that the observed improvements were due to factors other than the study medications; however this is unlikely given the low rate of response to placebo in a comparative trial in mixed-age patients (11). Finally, this randomized controlled trial lasted only nine weeks and it does not inform on the long-term tolerability and efficacy of lithium or divalproex in older persons with bipolar disorder.

The exploratory hypothesis testing reported presents examples of the important potential use of study data in further analyses. These include examination of potential moderators, such as illness course variables, and mediators of outcomes.

Our main findings, if confirmed, have implications for geriatric practice and investigation. Treatment with lithium or divalproex with conservative serum concentrations, combined with limited use of rescue and adjunctive medications, was tolerated by, and benefitted a substantial proportion of elders with mania. These results suggest that treatment guidelines for older persons with bipolar disorder should advocate for greater use of lithium and less exposure to antipsychotics. This approach may be particularly appropriate in elders since lithium may have neuroprotective (29) and anti-suicide (30) effects, while antipsychotics can be associated with serious adverse effects including premature mortality (31).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

*Members of the Geri-BD Study Group were: Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital: Laura D. Evans, MS, Sibel Klimstra, MD, Nabil Kotbi, MD, Michelle Gabriel, MS; Baylor College of Medicine: Christine Jacobson, Joseph Kwentus, MD, Lauren Marangell, MD; Case Western Reserve: Kristin Cassidy, Philipp Dines, MD, Luis Ramirez, MD; University of Pennsylvania: Michael Thase, MD, Dr. Bijan Etemad, Ruben Gur, Ph.D. Paul Moberg PhD, David Oslin, MD, Joel Streim MD, Thomas TenHave PhD, David Weiss, MD; Duke University: Patrick Connelly, Tracey Holsinger, K.R.R.Krishnan, MD, Mike Mani, Jody Miller, MD, Richard Weisler, MD; University of Pittsburgh/University of Toronto: James Emanuel, Adriana Hyams, Dielle Miranda, Bruce Pollock MD PhD, Tarek K. Rajii, MD, Kari Seals, Ellen Whyte, MD; NIMH: Elizabeth Zachariah.

The authors thank Mary Beth Keating for her assistance with manuscript preparation, Joanne Severe for her administrative support, and Barry D. Lebowitz, PhD for his encouragement.

Dr. Young has received support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Mulsant has received research support from Brain Canada, the CAMH Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the NIH, Bristol-Myers Squibb (medications for an NIH-funded clinical trial), and Pfizer (medications for an NIH-funded clinical trial). Within the past five years, he has also received some travel support from Roche. Dr. Sajatovic has received research grants from Pfizer, Merck, Ortho-McNeil Janssen, Reuter Foundation, Woodruff Foundation, Reinberger Foundation, NIH, and the Centers for Disease Control. She is a consultant to United BioSource Corporation (Bracket), Prophase, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Amgen and has received royalties from Springer Press, Johns Hopkins University Press, Oxford Press and Lexicomp. Dr. Gildengers has participated in scientific advisory board meetings for Shire Pharmaceuticals. Drs. Gyulai, Al Jurdi and Chen have no disclosures. Dr. Beyer has research support from Eli Lilly, Elan, Forest, Novartis, Sanofi: Astra-Zeneca, and Takeda. Drs. Marino and Bruce and Ms. Greenberg have had support from NIH. Drs. Kunik, Banerjee and Schulberg and Ms. Barrett have no disclosures. Dr. Reynolds receives research support from the NIH, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. He receives pharmaceutical supplies for his NIH-sponsored research from Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, and Lilly. Dr. Alexopoulos receives support from the NIH; he is on the speakers’ bureaus of Astra Zeneca, Forest, Novartis, and Sunovion. Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC provided risperidone to some sites.

Supported by U01 MH068846, U01 MH068847, U01 MH074511, R01 MH084921, K02 MH067028, K24 MH069430, P30 MH071944, P30 MH085943, P30 MH90333, UL1 RR024996, and UL1 RR024989 from the US Public Health Service.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT00254488

Contributor Information

Robert C. Young, Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital

Benoit H. Mulsant, University of Toronto/Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

Martha Sajatovic, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Ariel G. Gildengers, University of Pittsburgh

Laszlo Gyulai, University of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia VA Medical Center

Rayan K. Al Jurdi, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center

John Beyer, Duke University Medical College

Jovier Evans, National Institutes of Mental Health

Samprit Banerjee, Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital

Rebecca Greenberg, Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital

Patricia Marino, Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital

Mark E. Kunik, Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center

Peijun Chen, Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center

Marna Barrett, University of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia VA Medical Center

Herbert C. Schulberg, Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital

Martha L Bruce, Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital.

Charles F. Reynolds, III, University of Pittsburgh

George S. Alexopoulos, Weill Cornell Medicine and New York Presbyterian Hospital

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartels SJ, Forester B, Miles KM, Joyce T. Mental health service use by elderly patients with bipolar disorder and unipolar major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8(2):160–6. Epub 2000/05/10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gildengers AG, Butters MA, Chisholm D, Rogers JC, Holm MB, Bhalla RK, et al. Cognitive functioning and instrumental activities of daily living in late-life bipolar disorder. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(2):174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shulman KI, Tohen M, Satlin A, Mallya G, Kalunian D. Mania compared with unipolar depression in old age. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(3):341–5. Epub 1992/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bostwick JM, Pankratz VS. Affective disorders and suicide risk. American Journal Psychiatry. 2000;157:1925–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessing LV, Nilsson FM. Increased risk of developing dementia in patients with major affective disorders compared to patients with other medical illnesses. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;73 261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Jurdi RK, Marangell LB, Petersen NJ, Martinez M, Gyulai L, Sajatovic M. Prescription patterns of psychotropic medications in elderly compared with younger participants who achieved a “recovered” status in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(11):922–33. Epub 2008/11/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lala SV, Sajatovic M. Medical and psychiatric comorbidities among elderly individuals with bipolar disorder: a literature review. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(1):20–5. Epub 2012/04/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Himmelhoch JM, Neil JF, May SJ, Fuchs CZ, Licata SM. Age, dementia, dyskinesias, and lithium response. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137(8):941–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wertham FI. A group of benign chronic psychoses: prolonged manic excitements with a statistical study of age, duration and frequency in 2,000 manic attacks. Am J Psychiatry. 1929;86:17–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oostervink F, Boomsma M, Nolen W. Bipolar disorder in the elderly; different effects of age and of age of onset. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;116(3):176–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, et al. Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. The Depakote Mania Study Group. JAMA. 1994;271(12):918–24. Epub 1994/03/23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young RC, Gyulai L, Mulsant BH, Flint A, Beyer JL, Shulman KI, et al. Pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder in old age: review and recommendations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(4):342–57. Epub 2004/07/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shulman KI, Rochon P, Sykora K, Anderson G, Marndani M, Bronskill S, et al. Changing prescription patterns for lithium and divalproex in old age: shifting without evidence. Brit Med J. 2003;326:960–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoudemire A, Hill CD, Lewison BJ, Marquardt M, Dalton S. Lithium intolerance in a medical-psychiatric population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20(2):85–90. Epub 1998/05/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen ST, Altshuler LL, Melnyk KA, Erhart SM, Miller E, Mintz J. Efficacy of lithium vs valproate in the treatment of mania in the elderly: a retrospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaffer CB, Garvey MJ. Use of lithium in acutely manic elderly patients. Clin Gerontologist. 1984;3:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.First MB, Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV patient version (SCID-P). American Psychiatric Press, Inc. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity, and sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A rating scale for depression that is sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The UKU Side Effect Rating Scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1987;334(1):1–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otto MW, Reilly-Harrington N, Sachs GS, Knauz RO. Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program (STEP) for Bipolar Disorder. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, Docherty JP, Expert Consensus Panel for Using Antipsychotic Drugs in Older P. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65 Suppl 2:5–99. Epub 2004/03/05. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton M A rating scale for depression. Neuro Neurosurg Psychia. 1960;23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirschfeld RM, Bowden CL, Vigna NV, Wozniak P, Collins M. A randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of divalproex sodium extended-release in the acute treatment of mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(4):426–32. Epub 2010/04/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, Rendell J, Azorin JM, Cipriani A, Ostacher MJ, et al. Lithium plus valproate combination therapy versus monotherapy for relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder (BALANCE): a randomised open-label trial. The Lancet. 2010;375(9712):385–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowden CL, Janicak PG, Orsulak P, Swann AC, Davis JM, Calabrese JR, et al. Relation of serum valproate concentration to response in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(6):765–70. Epub 1996/06/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sproule B Lithium in bipolar disorder. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(9):639–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessing LV, Sondergard L, Forman JL, Andersen PK. Lithium treatment and risk of dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(11):1331–5. Epub 2008/11/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med Journal. 2013;346:f3646. Epub 2013/07/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):225–35. Epub 2009/01/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.