Abstract

Purpose:

Somatic mutations in the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-1 and -2 genes are remarkably penetrant in diffuse gliomas. These highly effective gain-of-function mutations enable mutant IDH to efficiently metabolize isocitrate to D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D 2-HG) that accumulates to high concentrations within the tumor microenvironment. D 2-HG is an intracellular effector that promotes tumor growth through widespread epigenetic changes in IDH mutant tumor cells, but its potential role as an intercellular immune regulator remains understudied.

Experimental Design:

Complement activation and CD4+, CD8+, or FOXP3+ T cell infiltration into primary tumor tissue were determined by immunohistochemistry using sections from 72 gliomas of World Health Organization (WHO) grade III and IV with, or without IDH mutations. Ex vivo experiments with D 2-HG identified immune inhibitory mechanisms.

Results:

IDH mutation associated with significantly reduced complement activation and decreased numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with comparable FOXP3+/CD4+ ratios. D 2-HG potently inhibited activation of complement by classical and alternate pathways, attenuated complement-mediated glioma cell damage, decreased cellular C3b(iC3b) opsonization, and impaired complement-mediated phagocytosis. While D 2-HG did not affect dendritic cell differentiation or function, it significantly inhibited activated T cell migration, proliferation, and cytokine secretion.

Conclusion:

D 2-HG suppresses the host immune system, potentially promoting immune escape of IDH-mutant tumors.

Keywords: Glioma, Oncometabolite, D-2-hydroxyglutarate, IDH, Complement, T cells

Introduction

Site-specific mutations of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-1 or -2 are present in 80-90% of patients with diffuse WHO grade II-III gliomas and a small subset of patients with WHO grade IV glioblastomas (1-4). IDH mutations are also present but less penetrant in acute myeloid leukemia (5), angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (6), and chondrosarcomas (7). However, precisely how IDH mutations might confer an advantage to tumorigenesis is not well-understood.

Missense mutations of R132 in IDH-1 or R172 in IDH-2 that change this arginyl residue to any of several other residues confer a remarkable gain-of-function to IDH catalytic activity enabling mutant enzyme to stereospecifically reduce isocitrate to D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D 2-HG) (2, 8, 9) rather than its normal product α-ketoglutarate. D 2-HG accumulates to 30 mM within (10) and 3 mM surrounding (11) gliomas carrying a mutant IDH-1 or IDH-2 gene. D 2-HG alters tumor cell metabolism and epigenetic regulation (12-14), but the full significance of IDH mutations or more precisely the unique nature of excessive D 2-HG accumulation is undefined. For instance, we now know that tumor IDH mutation tightly correlates to the absence of microthrombi within the tumor vasculature of diffuse gliomas, and that D 2-HG directly suppresses ex vivo activation and thrombosis of purified platelets (15). Potentially, then, tumor-derived D 2-HG functions as an intercellular mediator that affects non-neoplastic cells of the tumor microenvironment. Tumor-infiltrating CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells are present in the glioma microenvironment (16), and mutant IDH associates with fewer infiltrating immune cells, including macrophages, T cells, and B cells, in tumors (17-19), and IDH mutant gliomas may escape from natural killer (NK) cell immune surveillance by downregulation of their natural-killer group 2, member D (NKG2D) ligand expression (20).

Complement is a key component of the innate immune system that defends against pathogen invasion and clears apoptotic cells and immune complexes. When activated by either classical, alternative, or lectin pathways, activated complement forms membrane attack complex (MAC) pores that lyse targeted cells (21). Complement activation also leads the deposition of C3b(iC3b) fragments on target cells for “opsonization” that facilitates phagocytosis through interactions with C3b(iC3b) receptors (C3aR) expressed on phagocytes. Recent studies (22-24) also found that complement directly regulates T cell function, in part through signaling of G-protein coupled C3aR and C5aR receptors on antigen-presenting cells and T cells.

Here we determined whether the immunologic microenvironment of adult diffuse gliomas is affected by IDH mutational status. We find that IDH mutation associates with reduced complement activation, decreased CD4+, FOXP3+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration in gliomas in situ, and that D 2-HG directly suppresses these essential elements of both innate and adaptive immunity.

Material and Methods

Expanded Material and Methods are presented in a supplement to this article.

Patient tissue

Tissues were obtained from patients diagnosed with primary high-grade astrocytoma between 1997 and 2017. All tumor samples were classified or re-classified according to the WHO Classification 2016 (25). Patients underwent initial surgery at the Department of Neurosurgery, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, or at the Department of Neurosurgery, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany. None of the patients had received treatment prior to surgery. Of the 72 patients included in the current study, 23 were WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytomas and IDH-mutant (mIDH), 16 were WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytomas and IDH-wildtype (wtIDH), 14 were WHO grade IV glioblastomas with mIDH, and 19 were WHO grade IV glioblastomas with wtIDH. IDH status was determined by immunohistochemistry using an antibody against the most common IDH-1-R132H mutation (clone H14, Dianova, Germany) using the BenchMark Ultra IHC/ISH staining system (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA) (26), and/or by next-generation sequencing as previously described (27). Of the 37 detected IDH mutations, 31 were IDH-1-R132H, three were IDH-1-R132C, and one each corresponded to IDH-1-R132S, IDH-1-R132G or IDH-2 R140W.

Additionally, double immunohistochemistry with antibodies against C3/C3b and the tumor marker Oligodendrocyte transcription factor (OLIG2) was performed on six of the 72 astrocytomas included in the patient cohort (one mIDH and one wtIDH anaplastic astrocytoma, two mIDH and two wtDH glioblastomas) to verify and localize deposition of C3 on tumor cells.

Complement activation pathway assays

The potential effects of D 2-HG in inhibiting the classical and alternative pathways of complement activation were analyzed using antibody-sensitized sheep erythocytes (EshA ) or rabbit erythrocytes (Erabb) following well-established protocols (28).

Complement convertase assays

Complement convertases of the classical and alternative pathways were analyzed following a published protocol using EshA or Erabb (29, 30).

Complement –mediated tumor cytotoxicity assay

Complement-mediated brain tumor cell damage assay was done based on the measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage using a commercial kit (Sigma).

Complement C3b deposition assay

EshA were incubated with 2% C5-depleted serum in Gelatin veronal buffer with calcium and magnesium (GVB++ ) containing defined concentrations of D 2-HG. For negative controls, 5 mM EDTA was added to the buffer. After 10 minutes at 37°C, EshA were washed and stained with an Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated anti-human C3 antibody (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) for additional 30 min on ice, followed by flow cytometry analysis.

Complement opsonization-mediated phagocytosis assay

The myeloid cell line U937 was differentiated into macrophages for the complement opsonization-mediated phagocytosis assay based on a published protocol (31, 32).

T cell inhibition and migration assays

Nylon wool-enriched T cells, or negative selection-purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from WT mice were activated by monoclonal antibodies against CD3 and CD28, then cultured in different polarization conditions in the presence of different concentrations of D 2-HG. The inhibitory effect of D 2-HG was assessed by measuring the proliferation of the activated T cells using carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation. In addition, cytokines produced by the activated T cells were quantitatively assessed in the culture supernatants by ELISA and the generation of Tregs were assessed by analyzing CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ cells using flow cytometry.

Impact of D 2-HG on T cell migration was assessed in a conventional transwell migration assay.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cell differentiation and function assay

Dendritic cells (DCs) were generated from bone marrow using a published protocol (33), and their function was assessed using antigen-specific T cells from ovalbumin peptide 323-339 (OVA323-339 )-specific TCR transgenic mice (OT II mice) and ovalbumin peptide 257-264 (OVA257-264 )-specific TCR transgenic mice (OT I mice).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (Version 5). Mann-Whitney U test or Student’s unpaired t-test, as appropriate, were used to investigate the difference in protein expression between mIDH and wtIDH tumors. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction was used to analyze data of more than two groups and Student’s t-test was used to analyze data of two sets. p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

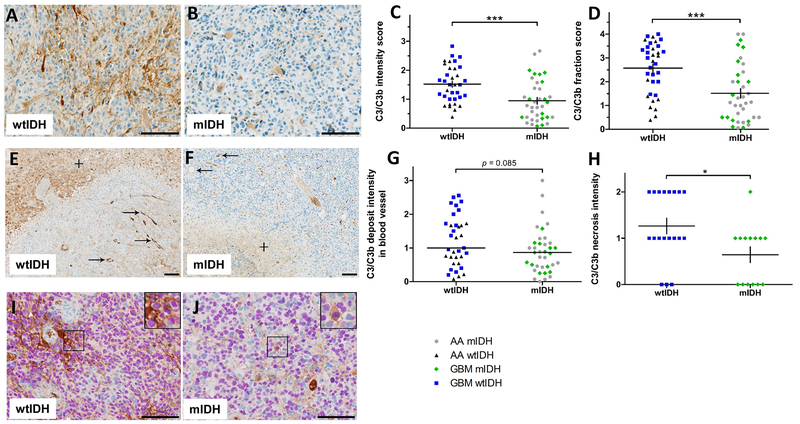

IDH mutations associate with decreased levels of complement activation in astrocytic brain tumors

To examine whether IDH mutational status, and thus the presence of excessive D 2-HG, associates with complement activation in the tumor microenvironment, we performed immunohistochemistry on tissue samples from 72 patients using an antibody against C3(C3b) fragments deposited on cell surfaces after activation of the complement cascade. We found in representative sections (Fig. 1A, B) that deposition of these complement fragments, assessed by their staining density, was less in tumors from the 37 patients with mIDH than in samples from 35 patients with wtIDH. Accordingly, the overall intensity (Fig. 1C) (p<0.001), and fraction score (Fig. 1D) (p<0.001) of C3(C3b) were lower in WHO grade III and IV astrocytomas with mIDH as compared to WHO grade III and IV astrocytomas with wtIDH (Suppl. Table 1). Similar results were found when separately analyzing C3(C3b) immunopositivity in the groups of anaplastic astrocytomas and glioblastomas (Suppl. Table 1). Further, we found that mIDH astrocytomas tended to have less complement deposition on the luminal surfaces of small blood vessel and capillaries compared to wtIDH tumors (p=0.085), and this was especially the case when looking separately at glioblastomas (p<0.01) (Fig 1E-G, and Suppl. Table 1). Additionally, the intensity of deposited C3(C3b) in necrotic zones was lower in mIDH glioblastomas than in wtIDH glioblastomas (Fig 1E, F, H, and Suppl. Table 1). Double-labelling with C3(C3b) and the tumor marker OLIG2 showed deposition of complement fragments in close proximity to OLIG2+ nuclei suggesting that C3(C3b) is also deposited on tumor cell surfaces. This was seen both in astrocytomas with wtIDH and mIDH (Fig.1I, J).

Figure 1. IDH mutations associate with diminished complement activation in astrocytic brain tumors.

Immunohistochemical staining for C3b(iC3b) deposition in tumor tissue sections from patients with anaplastic astrocytoma (AA) WHO grade III or glioblastoma (GBM) WHO grade IV. A, representative C3b(iC3b) staining of a section from an IDH-wildtype tumor (wtIDH) B, C3b(iC3b) staining of a section from an IDH-mutant tumor (mIDH). C, levels of complement activation semi-quantitated by C3b (iC3b) deposition intensity scores in anaplastic astrocytomas (AA) and glioblastomas (GBM). D, complement activation semi-quantitated by C3b (iC3b) deposition fraction scores in anaplastic astrocytomas and glioblastomas. E, F, representative C3b(iC3b) staining in small blood vessels (arrows) and necrotic areas (+) in sections of GBM samples. G, H, Complement activations in blood vessels and necrotic areas were semi-quantitated by C3b (iC3b) deposition intensity scores. I, J, C3b(iC3b)/OLIG2 double staining of sections from glioblastomas with wtIDH and mIDH. Each dot in panels C, D, G, H represents a single patient, *p<0.05; **, p<0.01; *** p<0.001. Scale bar 100 μm

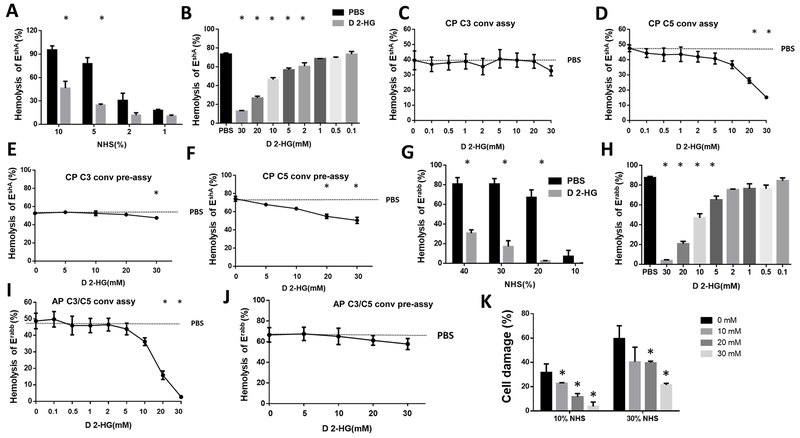

D 2-HG inhibits the classical pathway of complement activation

To explore the mechanism underlying the reduced complement activation/deposition in gliomas with IDH mutation, we used a conventional complement-mediated hemolytic assay to test whether D 2-HG inhibits the classical pathway of complement activation and the cellular lysis it generates through MAC complex formation (28). This experiment showed D 2-HG suppressed MAC-induced hemolysis, that suppression was a function of the concentration of normal human serum (NHS) and hence MAC complex abundance, and that this inhibition became statistically significant by 5% NHS (Fig. 2A). We also tested the effects of different concentrations of D 2-HG in this assay, using a fixed amount of NHS, to find that D 2-HG inhibited the classical pathway of complement activation in a dose-dependent manner with a minimally effective concentration of 2 mM (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. D 2-HG inhibits both the classical and alternative pathways of complement activation through distinct mechanisms.

A, D 2-HG reduces complement-dependent hemolysis as a function of complement concentration in normal human serum (NHS). Complement-mediated hemolysis by the classical pathway using EshA in the presence of varied concentrations of NHS in the absence or presence of 30 mM D 2-HG before hemolysis was quantitated. B, complement-mediated hemolysis by the classical pathway as a function of D 2-HG concentration using EshA in 5% NHS. C, effect of D 2-HG on assembly of C3 convertases of the classical pathway using EshA and C3-depleted serum. D, effect of D 2-HG on assembly of C5 convertases of the classical pathway using EshA and C5-depleted serum. E, effect of varied D 2-HG concentrations on the activity of pre-assembled C3 convertases of the classical pathway using EshA and C3-depleted serum. F, effect of varied D 2-HG concentrations on the activity of pre-assembled C3 convertases of the classical pathway using EshA and C5-depleted serum. G, effect of 30 mM D 2-HG on complement activation by the alternative pathway assessed by MAC-mediated Erabb hemolysis. H, concentration-dependent effect of D 2-HG in 20% NHS on alternative complement activation assessed by MAC-mediated Erabb hemolysis. I, effect of varied D 2-HG concentrations on assembly of C3/C5 convertases of the alternative pathway of complement activation using Erabb and C5-depleted serum. J, D 2-HG effect on the activity of pre-assembled C3/C5 convertases of the alternative pathway of complement activation using Erabb and C5-depleted serum as a function of D 2-HG concentration. K, concentration-dependent effect of D 2-HG in inhibiting different concentrations of complement(10% and 30% NHS)-mediated damage of antibody-sensitized T98 glioma cells. For all panels, PBS was used in all assays as control, and data are presented as mean ± SD that has been analyzed by Student’s t test and one-way ANOVA. *p<0.05. CP, classical pathway; AP, alternative pathway, conv, convertase, assy, assembly

D 2-HG inhibits assembly of C5, but not C3, convertase in the classical pathway of complement activation

D 2-HG could inhibit complement-mediated cell damage at multiple steps of the complement activation cascade. To explore underlying mechanisms, we determined whether D 2-HG affected assembly of C3 and C5 convertases leading to MAC complex-induced hemolysis (29). These assays showed D 2-HG had no effect on C3 convertase assembly in the classical pathway of complement activation (Fig. 2C) but significantly inhibited the assembly of C5 convertases of the classical pathway at concentrations of 20 mM and 30 mM (Fig. 2D)

D-2HG inhibits activity of assembled C3 and C5 convertases in the classical pathway of complement activation

To determine whether D 2-HG inhibits the activities of pre-assembled C3 and/or C5 convertases in the classical pathway of complement activation, we incubated EshA with C3- or C5-depleted serum alone to allow the assembly of C3 or C5 convertases and, after washing, we incubated these cells with guinea pig serum in the presence of EDTA (to prevent new convertase assembly) and different concentrations of D 2-HG to measure complement-mediated hemolysis (29). These experiments showed that D 2-HG modestly decreased complement-mediated hemolysis in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2E, F), indicating that D 2-HG can inhibit the activity of both assembled C3 and C5 convertases in the classical pathway of complement activation, and that D 2-HG is not inhibiting complement activity through simple Ca++ ligation (15).

D 2-HG inhibits the alternative pathway of complement activation

The alternative complement pathway is a distinct, major route for complement activation that additionally amplifies complement activation initiated through other pathways. To evaluate the potential effects of D 2-HG on this route to complement activation, we used an Erabb-based complement-mediated hemolytic assay (28). The results of this assay showed D 2-HG additionally inhibited the alternative pathway of complement activation (Fig. 2G). We then incubated Erabb with 20% NHS in the absence or presence of different concentrations of D 2-HG over the range from 0.1 to 30 mM, and found that D 2-HG also significantly reduced the complement-mediated hemolysis in a dose-dependent manner with a minimally required concentration of 5 mM (Fig. 2H).

D 2-HG inhibits the assembly of C3/C5 convertases in the alternative pathway of complement activation

To elucidate the mechanisms by which D 2-HG inhibits the alternative pathway of complement activation, we used convertase assays similar to the above-described protocol for the classical pathway, but with the Erabb as the complement activator (28, 29). Because both C3 and C5 convertases in the alternative pathway require C3b, these two enzymes cannot be distinguished by using C3- or C5-depleted sera. These experiments showed that at concentrations of 20 mM and 30 mM, D 2-HG significantly inhibited the assembly of the C3/C5 convertases of the alternative pathway (Fig. 2I).

D 2-HG does not inhibit the activity of pre-assembled C3/C5 convertases in the alternative pathway of complement activation

We next tested the effects of D 2-HG on pre-assembled C3/C5 convertases in the alternative pathway of complement activation by incubating Erabb with C5-depleted serum, washing the cells, then incubating them again with guinea pig serum in the presence of EDTA and varied amounts of D 2-HG. These experiments showed that D 2-HG did not significantly inhibit the activity of pre-assembled C3/C5 convertases in the alternative pathway of complement activation (Fig. 2J), so there are enzymatic and functional differences between preassembled and assembled convertases.

D 2-HG protects brain tumor cells from complement-mediated injury

The above studies based on complement-mediated hemolysis assays suggest that D 2-HG could inhibit complement activation, and thereby MAC-mediated brain tumor cell damage. To test this, we incubated antibody sensitized T98 glioblastoma cells with different concentrations of complement in the presence of varied D 2-HG concentrations, then evaluated the complement-mediated cell injury by measuring levels of LDH that leaked from the cells. These experiments showed that D 2-HG significantly inhibited cell injury from complement-mediated cellular damage in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2K).

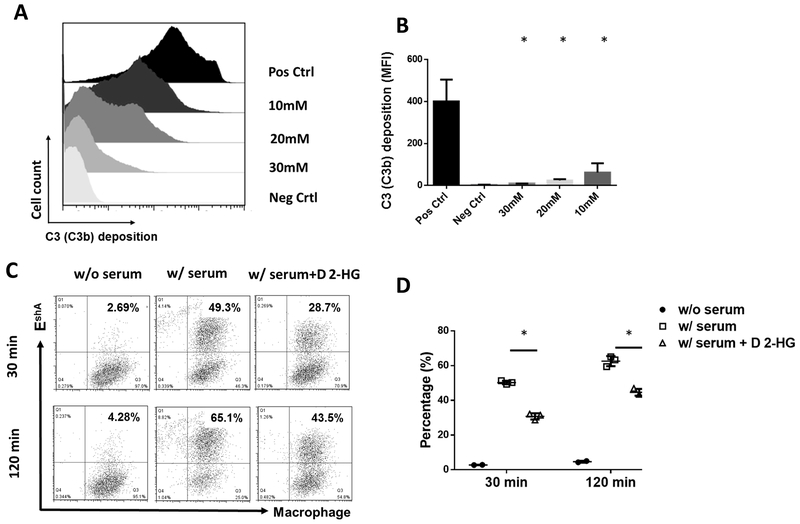

D 2-HG inhibits C3b(iC3b) opsonization and complement-mediated phagocytosis

In addition to the MAC formation, complement activation deposits C3b(iC3b) on target cells for opsonization that facilitates phagocytosis (34). To determine whether this complement function also was compromised by D 2-HG, we examined the effects of D 2-HG on both C3b(iC3b) opsonization and complement-mediated phagocytosis. We incubated EshA with C5-depleted serum (to avoid MAC formation and cellular lysis) in the presence of different concentrations of D 2-HG, then quantitated the levels of C3b(iC3b) deposited on the cell surface by flow cytometry. We found C3 deposition on the cells was significantly decreased by D 2-HG in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3 A, B). In parallel experiments to assess phagocytosis, we first incubated EshA with C5-depleted serum in the absence or presence of 30 mM D 2-HG, then fluorescently labeled them before mixing these cells with macrophages labeled with a different fluorophore. After incubation for either 30 or 120 minutes, phagocytosis was quantitated by analyzing the double-positive cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 3 C, D). This showed D 2-HG markedly reduced the efficiency of complement-mediated phagocytosis.

Figure 3. D 2-HG reduces complement opsonization–induced phagocytosis and complement-mediated glioma cell line damage.

A, representative flow cytometric histogram of C3b(i3Cb) deposition on the EshA cell surface in the presence of different concentrations of D 2-HG. For complement opsonization assays, EshA were incubated with 2% C5-depleted serum in the presence of the stated concentration of D 2-HG before C3b(iC3b) deposited on the cell surface was quantitated by flow cytometry. B, summarized results of the levels of C3b/i3Cb deposition on the cell surface in the presence of defined concentrations of D 2-HG as measured by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Pos Ctrl, positive control, cells were incubated with serum in the absence of D 2-HG; Neg Ctrl, negative control, cells were incubated with serum in the presence of EDTA (to completely inhibit complement activation), data are mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. * p<0.05. C, representative results of D 2-HG on phagocytosis. For complement-mediated phagocytosis assays, macrophages were prepared and labeled with CellTrace far-red fluorophore, while EshA were incubated with or without 2% C5-depleted serum in the absence or presence of 30 mM D 2-HG (for complement opsonization) and labeled with fluorescent DiI. Then the processed macrophages and EshA were co-cultured at a 1:10 ratio, and after either 30 or 120 min incubation the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to measure the efficiency of phagocytosis (frequency of double-positive cells). w/o serum, EshA were incubated without serum (no opsonization, negative control), w/serum, EshA were incubated with serum in the absence of D 2-HG (maximum opsonization, positive control), w/serum+ D 2-HG, EshA were incubated with serum in the presence of 30 mM D 2-HG. D, summarized results of phagocytosis assays. Data are mean ± SD and analyzed by student t test. * p<0.05

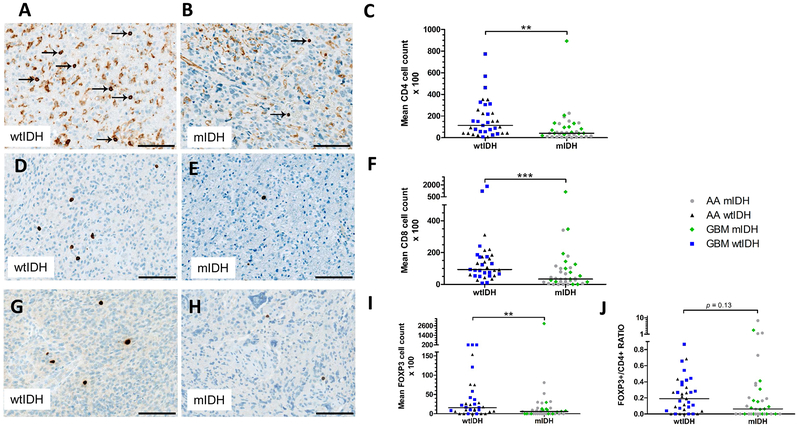

IDH mutations associate with decreased number of infiltrating lymphocytes in astrocytic brain tumors

To elucidate a potential association between IDH mutations and the adaptive immune system in patients with WHO grade III and IV astrocytomas, we quantitatively evaluated tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes by immunohistochemistry in the same 72 primary tumors we used to assess complement deposition (Fig. 1). We found fewer tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells in the group of mIDH gliomas than in the group of wtIDH gliomas of WHO grade III and IV (p<0.01) (Fig. 4 A- C). Similar outcomes were obtained when analyzing the subgroup of WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytomas (p<0.05) stratified according to IDH mutational status, with a similar tendency in subgroup of WHO grade IV glioblastomas (p=0.14) (Suppl. Table 1). We then investigated the infiltration of glioma tissues by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and observed decreased numbers of these cells in mIDH compared to wtIDH WHO grade III or IV gliomas (p<0.001) (Fig. 4 D- F). Again, this difference was also observed for the subgroup of anaplastic astrocytomas (p<0.01), with a similar tendency in the subgroup of glioblastomas that was not, however, significant (p=0.33). Interestingly, staining for the Treg cell marker FOXP3 showed that numbers of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ T cells were lower in mIDH grade III and IV gliomas compared to their wtIDH counterparts (Fig. 4G-I) (p<0.01) although since both FOXP3 positive and negative cells were decreased, the difference in the tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+/CD4+ ratio between the two groups was not statistically significant (p=0.13) (Fig. 4J).

Figure 4. IDH mutations associate with decreased numbers of infiltrating CD4+, CD8+ and FOXP3+ T cells in astrocytic brain tumors.

A, representative CD4+ immunohistochemistry in tumor sections from patients with WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytoma (AA) or WHO grade IV glioblastoma (GBM) wildtype IDH (wtIDH). Arrows indicate CD4+ T cells. B, representative CD4+ immunohistochemistry in tumor sections from patients with WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytoma or WHO grade IV glioblastoma with mutant IDH (mIDH). C, statistical analysis of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells in AA and GBM with wtIDH and mIDH. D, representative CD8 staining of tumor sections derived from a wtIDH tumor. E, representative CD8 staining of tumor sections derived from a mIDH tumor. F, statistical summary of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in AA and GBM tumors. G, representative FOXP3 immunostaining in sections obtained from a wtIDH astrocytoma. H, representative FOXP3 staining of tumor sections derived from with a mIDH astrocytoma. I, statistical summary of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3+ T cells and the ratio of FOXP3+ to total CD4+ T cells in AA and GBM sections. Each dot in all statistical analyses represents data from a single patient, **, p<0.01; *** p<0.001. Scale bar 100 μm

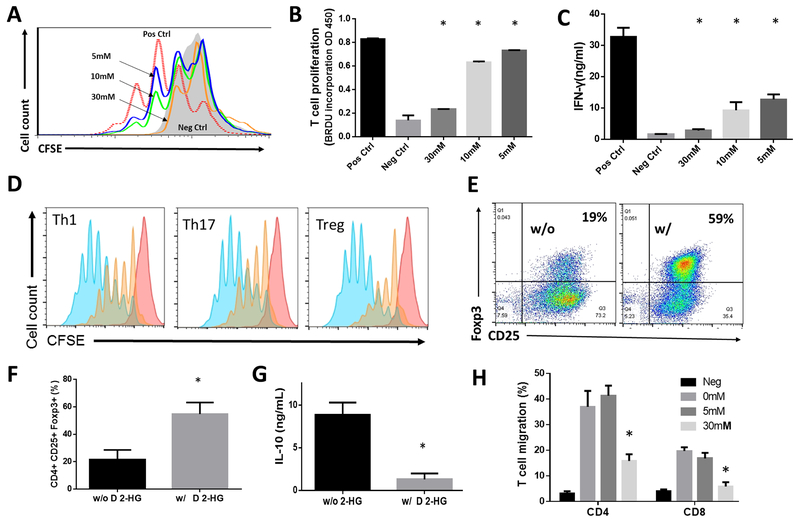

D 2-HG inhibits proliferation and cytokine production of activated T cells

While D 2-HG inhibits CD8+ T cell accumulation in tumors (17), whether it directly inhibits proliferation of activated T cells and/or stimulated cytokine production is unknown. We labeled purified T cells with fluorescent CFSE and activated them with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies in the absence or presence of D 2-HG at concentrations ranging from 5 to 30 mM. We then assessed proliferation of these activated T cells by CFSE dilution (Fig. 5A) to find D 2-HG significantly inhibited the proliferation of activated T cells. We confirmed this by assessing BrdU incorporation into the total DNA content of dividing cells (Fig. 5B). We also found that D 2-HG suppressed IFNγ production from the activated T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. D 2-HG inhibits proliferation of activated T cells and their cytokine production.

A, concentration-dependent inhibition of T cell proliferation by D 2-HG. T cells enriched from WT mice were labeled with CFSE and activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies in the presence of the stated concentration of D 2-HG. After 3 days of culture, CFSE dilution from the proliferation of the activated T cells was assessed by flow cytometry. B, statistical analysis of concentration-dependent inhibition of T cell proliferation by D 2-HG assessed by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation. C, statistical analysis of the concentration-dependent inhibition of IFNγ by D 2-HG assessed by ELISA. Pos Ctrl, positive control, T cells were activated in the absence of D 2-HG; Neg Ctrl, negative control, unactivated T cells; data were mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. * p<0.05 compared to the positive controls. D, histograms of concentration-dependent inhibition of proliferation of Th1 cells, Th17 cells and Tregs by D 2-HG. CD4+ T cells were purified from naïve WT mice, labeled with CFSE, activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies, and cultured under respective Th1, Th17 or Treg polarization conditions in the absence (blue peaks) or presence of 30 mM D 2-HG (orange peaks). Proliferations of these T cells were analyzed in three days by measuring the dilution of intracellular CFSE by flow cytometry. E, D 2-HG enhances CD4+CD25+ FOXP3+ Treg differentiation. Percentages of CD4+CD25+ FOXP3 + Tregs in the absence or presence of 30 mM D 2-HG were analyzed by flow cytometry. F, statistical analysis of the fraction of differentiated CD4+CD25+ FOXP3 + Tregs determined by flow cytometry. * p<0.05. G, D 2-HG inhibits IL-10 secretion by cultured CD4+CD25+ FOXP3 + Tregs determined by ELISA analysis of the cellular supernatants. H, D 2-HG inhibits T cell migration. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were isolated from naïve WT mice, and migration of these cells in the presence of the stated concentrations of D 2-HG in response to CCL19 was assessed in a standard transwell-based migration assay. * p<0.05

To test whether D 2-HG inhibits different subsets of effector CD4+ T cells, we isolated CD4+ T cells from naïve WT mice, activated them by monoclonal antibodies against CD3 and CD28, and cultured these cells in Th1, Th17 and Treg polarization conditions in the presence or absence of D 2-HG. We then assessed the proliferation of these various cells to find D 2-HG significantly inhibited proliferation of activated Th1, Th17 and Treg cells (Fig. 5D). Surprisingly, when we analyzed the differentiation of CD4+CD25+FOX3+ Treg cells in the presence of D 2-HG, we found that 30 mM D 2-HG significantly augmented differentiation of these cells (Fig. 5E, F). However, levels of IL-10 in the Treg culture supernatants were reduced in the presence of 30 mM D 2-HG. Thus while D 2-HG augments Treg differentiation, it concurrently inhibits proliferation of the differentiated Tregs (Fig. 5D). Accordingly, D 2-HG led to reduced numbers of tumor-infiltrating Tregs (Fig. 4G-I) in vivo and decreased production of IL-10 in vitro (Fig. 5G).

D 2-HG directly inhibits T cell migration

Inhibition of T cell proliferation by D 2-HG would reduce the presence of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in tumors from patients with mutant IDH, as would suppressed T cell migration. To address this question, we set up a transwell T cell migration assay following an established protocol using Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 19 (CCL19) as a chemoattractant to evaluate the effect of D 2-HG on T cell migration. These studies showed that 30 mM D 2-HG significantly inhibited the migration of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5H).

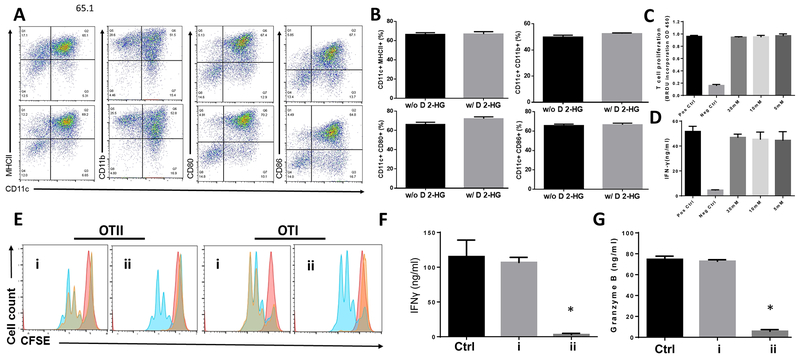

D 2-HG does not inhibit differentiation of dendritic cells (DC) or the function of differentiated DC

DCs are pivotal for T cell activation, so DCs were differentiated from bone marrow cells in the presence of defined concentrations of D 2-HG and then compared six days later to the DCs differentiated in the absence of D 2-HG using cell surface markers CD11c, MHCII, CD11b, CD80 and CD86. We found that D 2-HG, even at 30 mM, did not significantly impact the ratio of differentiated DCs (Fig. 6A , B), suggesting that D 2-HG does not indirectly suppress T cell function through DC differentiation.

Figure. 6. D 2-HG has no significant effect on DC differentiation or the function of differentiated DCs.

A, D 2-HG does not affect dendritic cell (DC) differentiation. DCs were differentiated from bone marrow cells in the absence or presence of 30 mM D 2-HG before surface markers on the surface of differentiated DCs were analyzed by flow cytometry. The top panel are untreated, and the bottom panel exposed to D 2-HG during differentiation. B, statistical analysis of D 2-HG effect on the fraction of cells expressing the stated surface antigen. C, D 2-HG fails to affect DC proliferation. DCs were differentiated in the presence of the defined concentrations of D 2-HG were cultured with CD4+ T cells from OT II mice together with OVA protein before the DC-activated T cells were assessed by measuring proliferation through BrdU incorporation. D, D 2-HG fails to affect DC function. IFNγ release in the forgoing panel was quantified by ELISA. E, D 2-HG has no effect on DC antigen processing/presentation, but inhibits antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Differentiated bone marrow-derived DCs were incubated with OVA protein in the absence or presence of 30 mM of D 2-HG, then washed and cultured with CD4+ T cells from OTII mice, or CD8+ T cells from OT I mice without further additional D 2-HG (i). As control, marrow derived-DCs incubated with OVA protein in the absence of D 2-HG were washed and cultured with CD4+ T cells from OTII mice, or CD8+ T cells from OTI mice together with 30 mM D 2-HG (ii). Proliferation of the DC-activated antigen-specific T cells were analyzed by CFSE dilution using flow cytometry. F, D 2-HG inhibits OT II CD4+ T cell release of INFγ. Statistical analysis of INFγ quantified by ELISA after DC-activated antigen-induced release. * p<0.05. G, D 2-HG inhibits OT I CD8+ T cell release of granzyme B. Statistical analysis of released granzyme B defined by ELISA in the supernatants from cultures including OT I CD8+ T cells. * p<0.05.

Even though D 2-HG did not have an appreciable effect on DC differentiation, it might still affect their function. We assessed this in the presence or absence of varied concentrations of D 2-HG by mixing the same numbers of these DCs with purified T cells from OT II transgenic mice that specifically recognize the ovalbumin 323-339 (OVA323-339 ) peptide together with this peptide antigen. We then compared proliferation of the OT II T cells activated by the DCs presenting the OVA peptide, again by BrdU incorporation, and quantified their functional response by IFNγ ELISA. These assays showed there was no appreciable difference between DCs differentiated in the absence or presence of D 2-HG in stimulating antigen-specific T-cell proliferation (Fig. 6C) or IFNγ production (Fig. 6D).

To determine whether D 2-HG affects DC antigen processing or presentation, and to confirm that D 2-HG inhibits antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, we first incubated DCs with OVA protein in the presence or absence of 30 mM D 2-HG for 4h, then washed the cells and incubated them with CD4+ T cells from OT II mice or CD8+ T cells from OT I mice for another three days. We then analyzed proliferation of the OVA-specific CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry, and measured levels of IFNγ produced from the activated CD4+ T cells, and levels of granzyme B produced from the activated CD8+ T cells in the culture supernatants by ELISA. These assays showed that both OVA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells had comparable proliferation (Fig. 6E) and produced similar levels of IFNγ (CD4+) (Fig. 6F) or granzyme B (CD8+) (Fig. 6G) after co-culturing with DCs incubated with OVA protein in the presence or absence of D 2-HG. This indicates that D 2-HG even at 30 mM has no effect on DC antigen processing or presentation. In contrast, when the same DCs with processed/presented OVA (in the absence of D 2-HG) were incubated with CD4+ T cells from OT II mice or CD8+ T cells from OT I mice with or without 30 mM D 2-HG, proliferation of the OVA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ were significantly inhibited by D 2-HG (Fig. 6E), as was their production of IFN-γ (CD4+) (Fig. 6F) or granzyme B (CD8+) (Fig. 6G). This shows D 2-HG directly inhibits antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells without interfering with DC antigen processing or presentation.

DISCUSSION

We report that IDH mutation associates with significantly decreased levels of complement deposition within human glioma tissues. From a molecular perspective, we found that D 2-HG inhibited both the classical and the alternative pathways of complement activation, reduced MAC-mediated cellular injury, and decreased complement-mediated opsonization and phagocytosis. We found that IDH mutation was also significantly associated with reduced numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ , CD8+ and FOXP3+ T cells in tumor tissue samples from patients with either WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytomas or WHO grade IV glioblastomas. In mechanistic studies, we found that, although D 2-HG did not inhibit the differentiation of DCs or their function after differentiation, D 2-HG directly suppressed proliferation of activated T cells and their production of key cytokines. These results elucidate a novel transcellular effect of tumor-derived D 2-HG on select cells and effector pathways of the immune system in a tumor microenvironment.

Complement forms a central part of the host immune surveillance mechanism against tumor cells, yet may have opposing roles in tumorigenesis because activated complement also promotes inflammation that favors tumor growth. Complement can be activated on tumor cells, either directly by the tumor cells themselves (35, 36) or by tumor-reactive antibodies that bind to neoantigens on the tumor cell surface, enabling MAC-mediated lysis and facilitated phagocytosis to dissolve the tumor (37). Conversely, tumors significantly upregulate expression of complement inhibitors including CD55 and CD59 on their surface that shield them from complement-driven attacks (38, 39). Our finding that D 2-HG significantly inhibited the activation of complement from both the classical and the alternative pathways suggest a new mechanism that would facilitate mIDH glioma cell survival. The classical pathway of complement activation is primarily initiated by antibody-antigen complexes. During tumor development, the proteome of the transformed cell includes neoantigens that can provoke B cell response to generate tumor-reactive antibodies against these neoepitopes. These anti-tumor antibodies, once bound to their antigens on tumor cell surface, initiate selective complement activation by binding circulating C1 molecules. This leads to MACs formation of transmembrane pores that permeabilize tumor cells, and additionally deposits C3b(iC3b) on the tumor cell surface to facilitate subsequent clearance by phagocytosis. The effect of the inhibition of the classical pathway activation of complement by D 2-HG would thus act to reduce the efficiency of anti-tumor antibodies in at least two ways.

In addition to direct attack by anti-tumor antibodies and their activation of complement through the classical pathway, altered expression patterns of surface molecules on tumor cells can trigger complement activation through the alternative pathway. This mechanism also forms MAC and deposits C3b(iC3b) on the target cells. Furthermore, the alternative pathway is a component of the amplification loop for complement activation initiated by other pathways, including the classical pathway (40). Complement is highly conserved among species, and we observed D 2-HG inhibited complement from normal mice, rats and guinea pigs (not shown). Thus, a propensity of D 2-HG to enhance tumorigenesis, in part, proceeds through effects on different routes to complement activation.

Our studies suggest that D 2-HG does not have a significant effect on at least the C3 convertases from the classical pathway of complement activation (Fig. 2). However, detection of deposited C3 antigens (C3b/iC3b) is robust. This suggests that alternative pathway might play a major role in activing complement in these tumors. In addition, our C3b uptake assays (Fig. 3) also suggest that even though D 2-HG might not have a drastic effect on the C3 convertases, it significantly inhibits the binding (deposition) of activated C3 onto the cell surface.

Inhibition of complement convertases by D 2-HG will be independent of Ca++ sequestration (15), since extracellular Ca++ significantly exceeds D 2-HG, although suppression of T cell function might reflect effective Ca++/ D 2-HG ligation at the far lower intracellular Ca++ levels (15). These new data also suggest that D 2-HG from the altered catalytic activity of mutant IDH in tumor cells has a profound role in suppressing both the innate and the adaptive immune systems that may underlie reduction of tumor-infiltrating T cells in human astrocytoma.

The adaptive immune system plays a vital role in tumor immune surveillance (41, 42) through tumor-reactive T cells, activated by tumor antigen-presenting cells such as DCs, to proliferate, release cytotoxins such as granzymes, and produce inflammatory cytokines including IFNγ. T cells also facilitate the humoral response to produce tumor-directed antibodies that activate complement on tumor cells leading to the assembly of MAC pores, lysis, and recognition and engulfment by macrocytic cells. Contravening this, tumor cells stimulate induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, upregulate programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (43) on their cell surface (44), and as we show here interfere with complement activation, and directly suppress T cell function.

We found that astrocytic gliomas expressing either mutant IDH-1 or IDH-2 contained significantly fewer tumor-infiltrating T cells relative to histologically similar tumors with wild-type IDH. Importantly, we show that the abundance of CD4+ helper cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, and total FOXP3+ Tregs were lower in gliomas with mutant as compared to tumors with wild-type IDH. Previously, the abundance of CD8+ cells in a smaller cohort glioblastoma patients was found to be reduced in tumors with mutant enzyme relative to tumors with wild-type enzyme (17), and we confirmed a reduction of these cells, but we also found fewer CD4+ and FOXP3+ T cells in a larger number of both WHO grade III and grade IV tumors. These data indicate that tumors expressing mutant IDH and synthesizing D 2-HG would be subject to lower levels of immune surveillance and immune-mediated elimination that includes reduced NK cell-mediated immunosurveillance (20).

The fact that any of the several mutations of IDH that induce the gain-of-function production of D 2-HG were associated with fewer tumor-infiltrating T cells suggests that the D 2-HG product itself is the likely functional effector limiting immunosurveillance. In a recent study (17), D 2-HG was found to suppress STAT1 activation and CD8+ T cell trafficking into gliomas correlating to loss of NK cell ligand expression (20). Additionally, we found D 2-HG inhibited the proliferation of activated T cells and their cytokine production which are central components of acquired immunity. However, in contrast to suppression of the proliferation of activated T cells and their production of cytokines, D 2-HG did not have an appreciable effect on DC differentiation or function, while it actually stimulated FOXP3+ CD4 T cell proliferation, although this occurred with sharp reduction of their stimulated function. This finding indicates that D 2-HG is selective in the cells and processes it inhibits and is not a general cytotoxin or cell cycle inhibitor.

The limitations of this study include that we postulate, but do not test, whether glioblastomas expressing IDH mutations abundantly release D 2-HG to their environment, similar to their extensive release of glutamate. The immune-inhibition we explore here occurs at the high D 2-HG levels found within or within centimeters of gliomas, but since the extracellular D 2-HG concentration in these locations is only modeled, we do not know the actual concentrations of D 2-HG experienced by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Additionally, this study correlates IDH mutational status in human glial tumors with reduced immune cell infiltration, but did not directly test the role of the IDH mutation in isolation using murine xenograft models.

Overall, our studies found that the over-production of D 2-HG in tumors expressing mutant IDH-1 and IDH-2 influences the tumor microenvironment by intervention in immunosurveillance at two key points, extracellular suppression of both classical and alternative complement deposition, as well as direct suppression of the T cell response. These results provide new insights into the mechanism by which the oncometabolite D 2-HG facilitates tumorigenesis of glioma cells carrying the IDH mutations.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

D 2-HG produced by gliomas expressing mutant IDH is an intercellular modulator inhibiting innate and adaptive immune systems. These new insights could aid the development of better immunotherapy for tumors with mutant IDH.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by grants NIH R01 DK 10358 (F. Lin), Cleveland Clinic Center of Excellence in Cancer-Associated Thrombosis Award (F. Lin and T.M. McIntyre), and VeloSano Pilot Project Award (T.M. McIntyre and F. Lin). We thank Justin D. Lathia for his helpful insights and discussions in creating and formulating this manuscript. We also thank technician Helle Wohlleben and senior histotechnician, project coordinator Ole Nielsen for assistance with immunohistochemical staining.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartmann C, Hentschel B, Wick W, Capper D, Felsberg J, Simon M, et al. Patients with IDH1 wild type anaplastic astrocytomas exhibit worse prognosis than IDH1-mutated glioblastomas, and IDH1 mutation status accounts for the unfavorable prognostic effect of higher age: implications for classification of gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:707–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartmann C, Meyer J, Balss J, Capper D, Mueller W, Christians A, et al. Type and frequency of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are related to astrocytic and oligodendroglial differentiation and age: a study of 1,010 diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:469–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mardis ER, Ding L, Dooling DJ, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Chen K, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1058–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns RA, Iqbal J, Lemonnier F, Kucuk C, de Leval L, Jais JP, et al. IDH2 mutations are frequent in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119:1901–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, Damato S, Halai D, Berisha F, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol. 2011;224:334–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462:739–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward PS, Patel J, Wise DR, Abdel-Wahab O, Bennett BD, Coller HA, et al. The common feature of leukemia-associated IDH1 and IDH2 mutations is a neomorphic enzyme activity converting alpha-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:225–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horbinski C. What do we know about IDH1/2 mutations so far, and how do we use it? Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:621–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linninger A, Hartung GA, Liu BP, Mirkov S, Tangen K, Lukas RV, et al. Modeling the diffusion of D-2-hydroxyglutarate from IDH1 mutant gliomas in the central nervous system. Neuro Oncol. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim SH, et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, Rohle D, Turcan S, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature. 2012;483:474–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koivunen P, Lee S, Duncan CG, Lopez G, Lu G, Ramkissoon S, et al. Transformation by the (R)-enantiomer of 2-hydroxyglutarate linked to EGLN activation. Nature. 2012;483:484–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unruh D, Schwarze SR, Khoury L, Thomas C, Wu M, Chen L, et al. Mutant IDH1 and thrombosis in gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:917–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domingues P, Gonzalez-Tablas M, Otero A, Pascual D, Miranda D, Ruiz L, et al. Tumor infiltrating immune cells in gliomas and meningiomas. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;53:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohanbash G, Carrera DA, Shrivastav S, Ahn BJ, Jahan N, Mazor T, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations suppress STAT1 and CD8+ T cell accumulation in gliomas. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1425–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amankulor NM, Kim Y, Arora S, Kargl J, Szulzewsky F, Hanke M, et al. Mutant IDH1 regulates the tumor-associated immune system in gliomas. Genes Dev. 2017;31:774–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berghoff AS, Kiesel B, Widhalm G, Wilhelm D, Rajky O, Kurscheid S, et al. Correlation of immune phenotype with IDH mutation in diffuse glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:1460–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Rao A, Sette P, Deibert C, Pomerantz A, Kim WJ, et al. IDH mutant gliomas escape natural killer cell immune surveillance by downregulation of NKG2D ligand expression. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:1402–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cravedi P, van der Touw W, Heeger PS. Complement regulation of T-cell alloimmunity. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33:565–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbore G, West EE, Spolski R, Robertson AAB, Klos A, Rheinheimer C, et al. T helper 1 immunity requires complement-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activity in CD4(+) T cells. Science. 2016;352:aad1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolev M, Le Friec G, Kemper C. Complement--tapping into new sites and effector systems. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahlrot RH, Kristensen BW, Hjelmborg J, Herrstedt J, Hansen S. A population-based study of low-grade gliomas and mutated isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1). J Neurooncol. 2013;114:309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zacher A, Kaulich K, Stepanow S, Wolter M, Kohrer K, Felsberg J, et al. Molecular Diagnostics of Gliomas Using Next Generation Sequencing of a Glioma-Tailored Gene Panel. Brain Pathol. 2017;27:146–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan BP. Complement methods and protocols. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blom AM, Volokhina EB, Fransson V, Stromberg P, Berghard L, Viktorelius M, et al. A novel method for direct measurement of complement convertases activity in human serum. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;178:142–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okroj M, Holmquist E, King BC, Blom AM. Functional analyses of complement convertases using C3 and C5-depleted sera. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passmore JS, Lukey PT, Ress SR. The human macrophage cell line U937 as an in vitro model for selective evaluation of mycobacterial antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell function. Immunology. 2001;102:146–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagata Y, Diamond B, Bloom BR. The generation of human monocyte/macrophage cell lines. Nature. 1983;306:597–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang AY, Golumbek P, Ahmadzadeh M, Jaffee E, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. Role of bone marrow-derived cells in presenting MHC class I-restricted tumor antigens. Science. 1994;264:961–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehlenberger AG, Nussenzweig V. The role of membrane receptors for C3b and C3d in phagocytosis. J Exp Med. 1977;145:357–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Praz F, Lesavre P. Alternative pathway of complement activation by human lymphoblastoid B and T cell lines. J Immunol. 1983;131:1396–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurita M, Matsumoto M, Tsuji S, Kawakami M, Suzuki Y, Hayashi H, et al. Antibody-independent classical complement pathway activation and homologous C3 deposition in xeroderma pigmentosum cell lines. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116:547–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers LM, Veeramani S, Weiner GJ. Complement in monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Immunol Res. 2014;59:203–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorter A, Meri S. Immune evasion of tumor cells using membrane-bound complement regulatory proteins. Immunol Today. 1999;20:576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fishelson Z, Donin N, Zell S, Schultz S, Kirschfink M. Obstacles to cancer immunotherapy: expression of membrane complement regulatory proteins (mCRPs) in tumors. Mol Immunol. 2003;40:109–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thurman JM, Holers VM. The central role of the alternative complement pathway in human disease. J Immunol. 2006;176:1305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swann JB, Smyth MJ. Immune surveillance of tumors. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho PC, Kaech SM. Reenergizing T cell anti-tumor immunity by harnessing immunometabolic checkpoints and machineries. Curr Opin Immunol. 2017;46:38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao S, Chen L. Adaptive resistance: a tumor strategy to evade immune attack. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:576–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alsaab HO, Sau S, Alzhrani R, Tatiparti K, Bhise K, Kashaw SK, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Signaling Inhibition for Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanism, Combinations, and Clinical Outcome. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.