Abstract

Rape by an intimate partner frequently involves a precedence of sexual consent between victim and perpetrator, often does not include the use of physical force, and may not fit societal definitions of rape. Given these unique characteristics, women who are assaulted by an intimate partner may be less likely to acknowledge the experience as a rape. In turn, they might make fewer blame attributions toward themselves and their perpetrators than victims of rape by a non-intimate partner. Consistent with these expectations, results from 208 community women reporting rape in adulthood revealed the presence of indirect effects of perpetrator type (non-intimate partner vs. intimate partner) on both behavioral self-blame and perpetrator blame through rape acknowledgment, even when controlling for both victim substance use at the time of the assault and coercion severity. Compared with women who experienced a rape by a non-intimate partner, women who experienced rape in the context of a marital or dating relationship were less likely to blame themselves or the perpetrator for the assault, in part because they were less likely to label their experience as a rape. Overall, these findings highlight the unique nature of intimate partner rape and provide further information about the relatively under-researched area of sexual violence in intimate relationships.

Keywords: violence, sexual coercion, victim-offender relationship, intimate partner sexual assault, marital rape

Following a sexual assault, victims often struggle with attributions of blame and responsibility. The degree to which sexual assault victims hold themselves (i.e., self-blame) and the perpetrator (i.e., perpetrator blame) responsible has been linked to many aspects of post-assault recovery. Those who engage in greater self-blame report more psychological distress (Frazier, 2003), depression (Frazier, 1990), and problem drinking (Sigurvinsdottir & Ullman, 2015), as well as reduced psychological well-being (Branscombe, Wohl, Owen, Allison, & N’gbala, 2003). Self-blame also predicts poorer risk recognition, decreased sexual refusal assertiveness, and increased chances of revictimization (Katz, May, Sörensen, & DelTosta, 2010; Miller, Markman, & Handley, 2007). Though perpetrator blame has rarely been examined in the context of sexual assault outcomes, Donde (2016) recently found that victims who place more blame on the perpetrator tend to believe sexual assault is less likely to occur in the future. This suggests that perpetrator blame may serve to increase victims’ perceived safety.

Given the consequential role of blame attributions in victims’ recovery from sexual assault, researchers have made efforts to identify the key factors shaping these attributions (e.g., victims’ use of substances, perpetrators’ use of physical force; Brown, Testa, & Messman-Moore, 2009). In the present study, we add to this literature by examining the impact of perpetrator type (i.e., intimate partner vs. non-intimate partner) on victims’ attributions of blame for sexual assault (both self- and perpetrator-focused). Although intimate partner can be defined in a number of ways, we focus on assaults by a current dating partner or spouse because these incidents occur within the context of an ongoing committed relationship and, thus, may involve unique dynamics particularly worthy of consideration as detailed below.

Perpetrator Type and Victims’ Blame Attributions

Intimate partners perpetrate over half of all sexual assaults against women (Black et al. 2011; Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, 2007). Experiencing a rape by a spouse or current dating partner may be qualitatively different from experiencing a rape perpetrated by a stranger or acquaintance and, thus, may result in unique blame attributions. However, due to methodological limitations, the existing literature in this area is somewhat inconclusive. For example, though early examinations of marital rape victims suggested a high degree of self-blame in this population (e.g., Bergen, 1996; Finkelhor & Yllo, 1982; Frieze, 1983), these studies did not compare levels of self-blame among marital rape victims with those of other rape victims. Furthermore, a number of studies have assessed observers’ (rather than victims’) blame attributions in response to hypothetical sexual assault scenarios presented in the form of vignettes (e.g., Ayala, Kotary, & Hetz, 2015; Grubb & Harrower, 2009; Langhinrichsen-Rohling & Monson, 1998; Monson, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & Binderup, 2000). However, given recent findings that victims and third-party individuals differ significantly in their perceptions of sexual assault (Perilloux, Duntley, & Buss, 2014), it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from such studies.

The few studies that directly examine associations between perpetrator type and victims’ blame attributions have yielded mixed findings. Donde (2015) reported that the victim’s level of acquaintance with the perpetrator (i.e., “How well did you know him?”) was not uniquely associated with any type of blame attribution. However, Frazier and Seales (1997) found that victims of stranger rape engaged in less behavioral self-blame than victims of rape by acquaintances. In that study, however, “acquaintances” included friends, dates, boyfriends, husbands, and other family members. Thus, Frazier and Seales’s (1997) findings do not reveal whether rape by an intimate partner (vs. strangers) is related to unique attributions of blame.

Despite the limited and mixed empirical evidence in this area, theory supports the premise that victims of intimate partner rape (IPR) may engage in less self- and perpetrator-blame than victims of rape by other perpetrators. First, IPR is less likely to involve the stereotypical risk factors associated with self-blame. Researchers have indicated that some victims blame themselves for engaging (or not engaging) in particular behaviors prior to or during the assault (e.g., being out late, walking alone, going to the perpetrator’s residence; Janoff-Bulman, 1979). Although these behaviors may play a role in some types of sexual assault (e.g., stranger rape), IPR occurs in a relational context often characterized by perceived safety and trust between partners. In the absence of these stereotypical risk factors, victims of IPR may believe that they had little control over the assault and, thus, may be less likely than victims of other sexual assaults to engage in behavioral self-blame.

Likewise, the victim’s ongoing relationship with the perpetrator may impact her perceptions of perpetrator blame. An IPR victim’s broader knowledge of the perpetrator—including familiarity with his positive qualities as well as more typical (non-assaultive) behaviors—may facilitate her ability to generate innocuous explanations for his behavior. As a result, victims may be less likely to blame intimate partners for assaults they commit and instead attribute these assaults to other factors (e.g., alcohol intoxication). By contrast, in cases of stranger- or acquaintance-perpetrated rape, a victim may have little information about the perpetrator beyond his actions surrounding the assault (e.g., encouraging her to drink to excess, ignoring her requests to stop), resulting in clearer perpetrator blame.

Perpetrator Type and Victims’ Rape Acknowledgment

Given that so few studies have investigated the link between perpetrator type and victims’ blame attributions, it is not surprising that no studies (to our knowledge) have sought to identify the mechanisms underlying this association. Based on related theoretical and empirical evidence, we postulate that rape acknowledgment is one factor that may function in this manner. Prior studies indicate that over half of all rapes are unacknowledged (Wilson & Miller, 2016) and thus not labeled by the victim as “rape,” with most unacknowledged victims instead describing their experience as a miscommunication (Layman, Gidycz, & Lynn, 1996). To explain this phenomenon, researchers have drawn on script theory (Littleton, Rhatigan, & Axsom, 2007), which suggests that individuals have cognitive scripts containing information about the way certain events typically occur (Fiske & Taylor, 1991). Rape scripts are, in part, informed by larger societal expectations and, thus, often represent rape as an incident perpetrated by a stranger that involves physical resistance by the victim (Littleton, Breitkopf, & Berenson, 2007). IPR strays from this script in that victims are less likely to use physical resistance tactics (Turchik, Probst, Chau, Nigoff, & Gidycz, 2007). According to this theory, scripts play a key role in the cognitive processing of events. Thus, the mismatch between the victim’s perceptions of her IPR experience and her “rape script” may lead the victim to interpret the event in a more benign manner (e.g., a miscommunication) rather than labeling it a rape (Cleere & Lynn, 2013; Kahn, Jackson, Kully, Badger, & Halvorsen, 2003; Koss, 1985; see Fisher, Daigle, Cullen, & Turner, 2003 for an exception).

A history of consensual sexual activities with the perpetrator may also influence victim acknowledgment of IPR (Logan, Walker, & Cole, 2015). This precedence of consent may promote an assumption of generalized, continuous consent for all future sexual activities (regardless of in-the-moment consent). This notion is supported by vignette studies assessing participants’ perceptions of consent in ambiguous sexual scenarios (Monson et al., 2000; VanZile-Tamsen, Testa, & Livingston, 2005). In one such study, Humphreys (2007) found that undergraduates were more likely to perceive consent as the degree of prior sexual intimacy between partners increased. This precedence of consent may make women who have been sexually victimized by an intimate partner more hesitant to label their experience as a rape even when consent is not given for a particular sexual experience.

Finally, we posit that IPR victims’ commitment to their partners may also inhibit rape acknowledgment. Cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957) suggests that individuals experience discomfort when their beliefs and behaviors are inconsistent with one another, resulting in an uncomfortable state of dissonance. Resolving this dissonance requires changing either one’s beliefs or behaviors so the two are aligned. Applied in the context of rape acknowledgment, this theory suggests that labeling an experience a rape may result in substantial dissonance if a victim does not wish to confront her partner or consider the possibility of ending the relationship. Practical exigencies (e.g., financial or housing security, shared custody of children) may also heighten cognitive dissonance (Whiting, Oka, & Fife, 2012). In noting this dilemma, Bergen (1996) quoted a survivor of marital rape as saying, “If you define it as rape, then you have to do something about it. So it’s easier to continue the denial” (p. 50). To reduce the psychological discomfort associated with dissonance and restore a sense of consistency, victims of IPR may be less likely to acknowledge the experience as rape.

Rape Acknowledgment and Blame Attributions

Together, the above findings and theory suggest that victims of IPR (vs. other types of sexual assault) may be less likely to label their unwanted sexual experiences as rape. We postulate that victims who do not recognize their experience as rape will, in turn, report lower levels of both self- and perpetrator-blame for the incident. If, for example, a victim views the experience as something other than rape (e.g., a misunderstanding), then she may not deem it a blameworthy event. This lack of acknowledgment of an experience as rape and related absence of blame attributions for the unwanted sexual experience may serve to protect victims from the societal stigma surrounding sexual assault (Bondurant, 2001; Neville & Heppner, 1999; Ward, 1995). By contrast, those who acknowledge their experiences as rape may be more vulnerable to internalizing societal stigma and beliefs about victim culpability.

Supporting possible links between rape acknowledgment and blame, prior work shows that victims who do not label their experiences as rape report less self-blame than those who do (i.e., a positive association; Bondurant, 2001; Orchowski, Untied, & Gidycz, 2013). Although other studies have found either a negative association (Botta & Pingree, 1997; Frazier & Seales, 1997) or no association (Layman et al., 1996) between acknowledgment and self-blame, these studies were restricted to small college samples (Frazier & Seales, 1997; Layman et al., 1996) or participants who provided at least some acknowledgment that their experiences were assaultive (Botta & Pingree, 1997)—which may have limited their generalizability. In contrast to the mixed findings regarding rape acknowledgment and self-blame, rape acknowledgment has consistently been linked to greater perpetrator blame (Botta & Pingree, 1997; Cleere & Lynn, 2013; Kahn et al., 2003; Orchowski et al., 2013). For example, Kahn and colleagues (2003) found that whereas 68% of women who labeled their experience as rape mentioned perpetrator blame when describing the victimization, only 24% of those not using the label “rape” discussed blaming the perpetrator. Similarly, we expect that greater rape acknowledgment will be associated with more perpetrator blame.

Summary and Current Study

Although IPR represents a substantial portion of sexual assaults and likely differs from stranger or acquaintance rape in important ways, we are aware of no efforts to examine whether attributions of blame differ for women who have experienced IPR versus victimization by strangers or acquaintances. Moreover, the potential mechanisms underlying any associations between perpetrator type and victims’ blame attributions are unknown. Regarding this question, prior theory and research suggest that women’s acknowledgment of their victimization experiences as rape (or not) may play a role in determining blame attributions for victims of IPR and other forms of sexual assault.

To address these gaps, this study tested the following hypotheses: (1) compared with victims of rape by any other perpetrator, victims of IPR would endorse (a) less behavioral self-blame and (b) less perpetrator blame; (2) compared with victims of rape by any other perpetrator, victims of IPR would be less likely to acknowledge their experience as rape; and (3) rape acknowledgment would be associated with (a) less behavioral self-blame and (b) less perpetrator blame. We also hypothesized (4) indirect effects of perpetrator type on both (a) self-blame and (b) perpetrator blame through rape acknowledgment.

Finally, to test the above hypotheses most rigorously, we controlled for victim substance use prior to the assault and severity of sexual coercion tactics in all analyses. Both factors have been linked to rape acknowledgment and blame attributions. Specifically, victims of substance-involved (vs. non-substance-involved) sexual assaults report greater self-blame and less perpetrator blame, and victims of assaults involving more severe coercion tactics are more likely to acknowledge their experience as rape (e.g., Brown et al., 2009; Cleere & Lynn, 2013; Donde, 2015; Kahn et al., 2003; Macy, Nurius, & Norris, 2006, 2007; Peter-Hagene & Ullman, 2014).

Method

Participants

Participants were community women recruited at four sites (Lincoln, Nebraska; Omaha, Nebraska; Jackson, Mississippi; Oxford, Ohio) as part of a larger multi-wave study of sexual revictimization. Women aged 18 to 25 were recruited (regardless of victimization history) by way of flyers, newspaper classified listings, and online advertisements for a study on “women’s life experiences and adjustment.” Of the 491 women who completed the first assessment, 208 (42.4%) reported experiencing rape in adulthood and were therefore included in the current analyses. All participants were 18 to 25 years old (M = 22.3, SD = 2.1); 72.6% were European American, 26.9% African American, 5.9% Latina, 3.4% American Indian, 3.4% Asian, and 1.4% other (participants could endorse more than one ethnicity). Just over half the participants (53.6%) were part-time or full-time students. The majority (79.6%) of participants self-identified as heterosexual, with the remainder identifying as bisexual (11.7%), gay/lesbian (4.9%), or questioning (3.9%).

Measures

Sexual assault characteristics.

The Modified Sexual Experiences Survey (Messman-Moore, Walsh, & DiLillo, 2010), an expanded version of the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss, Gidycz, & Wisiniewski, 1987), was used to assess unwanted sexual experiences with men in adulthood. Behaviorally-specific questions were used to assess sex acts (oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse; digital penetration; penetration by an object) that occurred as a result of verbal coercion, misuse of a position of authority, or physical force, or when the participant was incapable of consent due to drugs or alcohol. These criteria are consistent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (2012) definition of rape, which includes any “[p]enetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim” (p. 7). Participants who reported one or more of these incidents were asked a series of follow-up questions about the assault they identified as most distressing. Only those who endorsed some form of penetration during their most distressing assault were included in the current analyses. Participants reported the nature of their relationship to the perpetrator by checking as many descriptors as applicable. Perpetrator type for the index assault was dichotomized to intimate partner (a “spouse” or “current steady dating partner [e.g., boyfriend]”)1 or non-intimate partner (any other relationship). All participants were asked to respond “yes” or “no” to the statement, “I believe I was a victim of rape”; rape acknowledgment was indexed as a “yes” response to this statement. To assess victim substance use prior to the assault, participants were asked, “Were you using alcohol or drugs just before or during the unwanted sexual activity?” (response options were 0 = no, 1 = yes). A score was created to represent the most severe coercion tactics endorsed (0 = none, 1 = verbal tactics, 2 = threats of physical harm, 3 = physical harm).

Blame attributions.

The Behavioral Self-Blame and Rapist Blame subscales of the Rape Attribution Questionnaire (RAQ; Frazier, 2003) both consist of five questions beginning with the stem, “How often have you thought: This happened to me because….” Responses are indicated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). To soften the language for participants who may not acknowledge their experience as rape, sentence stems in the Rapist Blame scale were modified from “The rapist…” to “The guy….” Alpha coefficients for the Behavioral Self-Blame and Rapist Blame scales in the current study were .895 and .852, respectively. Prior research has supported the criterion validity of these subscales as demonstrated by expected correlations with a variety of related constructs (Frazier, 2003).

Procedure

All methods received prior approval by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions. After providing informed consent, participants completed a series of questionnaires on a computer in the laboratory, along with other laboratory-based tasks not included in this study. Participants received $75 for completing this laboratory session.

Analytic Approach

Graded response polytomous item factor analyses using a probit link with diagonally-weighted least squares estimates were conducted in Mplus v. 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012) with item response options examined as ordinal data. Prior to examining the hypothesized model, the measurement model for latent traits representing the Behavioral Self-Blame and Rapist Blame scales was first examined. Based on recommendations for the RAQ (Frazier, 2003), a two-factor measurement model with five items for each factor was initially hypothesized. Factor variances for each scale were held at 1 for identification. The resulting model had a significant p value for the χ2 test of absolute model fit and an RMSEA significantly greater than .05. However, this model achieved adequate fit globally as indicated by a CFI of .966 and a TLI of .955. Any model respecifications were not conceptually supported given the differences in item wording between subscales. As such, the original two-factor measurement model was retained. Effect sizes across indicators (i.e., standardized loadings in this model) ranged from .760 to .952. As indicated by residuals for estimated correlations, there was some relative local misfit between Behavioral Self-Blame items 1 (“I used poor judgment”) and 3 (“I just put myself in a vulnerable situation”), as well as between Rapist Blame items 1 (“The guy thought he could get away with it”) and 4 (“The guy was angry at women”). A tau-equivalent (i.e., Rasch) model in which items were assumed to be equally discriminating (i.e., loadings were constrained to be equal) fit significantly worse (p < .001) than a model in which each loading was estimated, so the latter model with separate estimates for each factor loading was retained.

After examining a measurement model, all four hypotheses were examined simultaneously using a structural equation model. Specifically, the direct effects of perpetrator type on Behavioral Self-Blame and Rapist Blame, and the indirect effects via rape acknowledgment, were examined. Victim substance use and coercion severity were allowed to covary with each variable (perpetrator type, acknowledgment, Behavioral Self-Blame, Rapist Blame). The latent traits representing Behavioral Self-Blame and Rapist Blame were also allowed to covary. Bias-corrected confidence intervals (95% CIs) of all parameter estimates were estimated using 5000 bootstrap resamples. CIs not including zero reflect an effect that is present. Given that dichotomous predictors were included in the model, unstandardized coefficients are reported (Hayes, 2013). Finally, we considered the possibility of reverse causality by examining a model in which the mediator and outcome were switched. Specifically, we examined the indirect effect of perpetrator type on rape acknowledgment through Behavioral Self-Blame and Rapist Blame, controlling for victim substance use and coercion severity.

Results

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations are provided in Table 1. With regard to characteristics of the index (most distressing) assault, 50 (24.0%) participants identified their perpetrator as a current intimate partner and 104 (50.0%) reported using substances prior to the rape. In addition, although all participants endorsed behaviorally-specific items indicative of rape, only 65 (31.6%) participants identified the experience as rape (referred to as rape acknowledgment). Specifically, 8 (16.0%) women raped by an intimate partner acknowledged their experience as rape, and 57 (36.5%) women raped by a non-intimate partner acknowledged their experience as rape. Behavioral Self-Blame scores ranged from 1 to 5 and were significantly lower for IPR victims (M = 2.52, SD = 1.31) than victims of rape by other perpetrators (M = 3.65, SD = 1.12), t(206) = 5.96, p < .001. Rapist Blame scores ranged from 1 to 5 and did not differ between IPR victims (M = 1.97, SD = 1.17) and victims of rape by other perpetrators (M = 2.28, SD = 1.13), t(206) = 1.71, p = .088.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations (N = 208).

| Correlations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. Behavioral Self-Blame | 1 – 5 | 3.38 (1.26) | |||||

| 2. Rapist Blame | 1 – 5 | 2.21 (1.15) | .487** | ||||

| 3. Perpetrator Type (Non-intimate partner vs. intimate partner) | 0 – 1 | 0.24 (0.43) | −.383** | −.118 | |||

| 4. Rape Acknowledgment | 0 – 1 | 0.32 (0.47) | .391** | .555** | −.189** | ||

| 5. Victim Substance Use | 0 – 1 | 0.50 (0.50) | .239** | −.080 | −.338** | −.017 | |

| 6. Coercion Severity | 0 – 3 | 1.57 (1.13) | .238** | .518** | −.024 | .422** | −.231** |

Note:

p < .05

p < .01

SD = Standard Deviation. Perpetrator type was coded such that 0 = non-intimate partner, 1 = intimate partner defined as current spouse or dating partner. The mean can therefore be interpreted as the percent of the sample (24%) whose rape was committed by an intimate partner. Rape acknowledgment was coded such that 0 = no and 1 = yes. The mean can therefore be interpreted as the percent of the sample (32%) who acknowledged experiencing a rape. Victim substance use was coded such that 0 = no and 1 = yes. The mean can therefore be interpreted as the percent of the sample (50%) who reported using a substance prior to the assault.

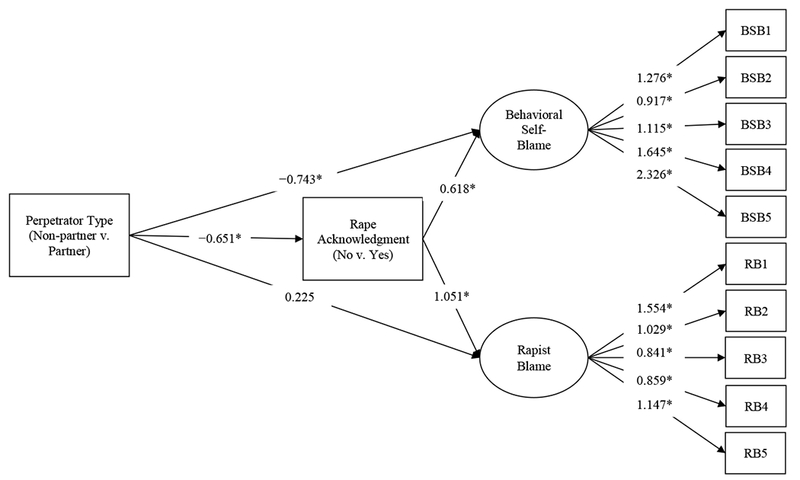

All four hypotheses were examined simultaneously (see Table 2, Figure 1). All effects were estimated while controlling for victim substance use and coercion severity.2 In support of Hypothesis 1a, when controlling for rape acknowledgment, a negative direct effect of perpetrator type on Behavioral Self-Blame was present (b = −0.743, SE = 0.219, 95% CI: −1.183, −0.317), indicating that victims of IPR endorsed less self-blame than victims of rape by any other perpetrator. However, in contrast to Hypothesis 1b, when controlling for rape acknowledgment, the direct effect of perpetrator type on Rapist Blame was not present (b = 0.225, SE = 0.318, 95% CI: −0.333, 0.892), indicating that attributions of perpetrator blame did not vary between victims of IPR and women raped by other perpetrators. Further, in support of Hypothesis 2, a negative direct effect of perpetrator type on rape acknowledgment was present (b = −0.651, SE = 0.251, 95% CI: −1.165, −0.192), indicating that victims of IPR were less likely to identify their experience as rape than women raped by other perpetrators. Moreover, in support of Hypotheses 3a and 3b, when controlling for perpetrator type, there were positive direct effects of rape acknowledgment on both Behavioral Self-Blame (b = 0.618, SE = 0.136, 95% CI: 0.373, 0.907) and Rapist Blame (b = 1.051, SE = 0.185, 95% CI: 0.753, 1.448). In other words, individuals who did not label their experience as rape made fewer blame attributions.

Table 2.

Structural equation model results.

| Unstandardized Estimate | SE | [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loadings: Behavioral Self-Blame (BSB) | |||

| Item 1 | 1.276 | 0.171 | [0.993, 1.673]* |

| Item 2 | 0.917 | 0.132 | [0.689, 1.203]* |

| Item 3 | 1.115 | 0.167 | [0.838, 1.493]* |

| Item 4 | 1.645 | 0.241 | [1.264, 2.243]* |

| Item 5 | 2.326 | 46.184 | [1.696, 3.721]* |

| Factor Loadings: Rapist Blame (RB) | |||

| Item 1 | 1.554 | 15.997 | [1.046, 2.781]* |

| Item 2 | 1.029 | 0.176 | [0.756, 1.471]* |

| Item 3 | 0.841 | 0.144 | [0.598, 1.177]* |

| Item 4 | 0.859 | 0.144 | [0.622, 1.205]* |

| Item 5 | 1.147 | 0.179 | [0.861, 1.579]* |

| Direct Effects | |||

| Perpetrator Type → BSB | −0.743 | 0.219 | [−1.183, −0.317]* |

| Perpetrator Type → RB | 0.225 | 0.318 | [−0.333, 0.892] |

| Perpetrator Type → Acknowledgment | −0.651 | 0.251 | [−1.165, −0.192]* |

| Acknowledgment →BSB | 0.618 | 0.136 | [0.373, 0.907]* |

| Acknowledgment → RB | 1.051 | 0.185 | [0.753, 1.448]* |

| Covariances | |||

| BSB with RB | 0.425 | 0.094 | [0.237, 0.612]* |

| Victim Substance Use with Perpetrator Type | −0.179 | 0.033 | [−0.241, −0.110]* |

| Victim Substance Use with Acknowledgment | −0.145 | 0.115 | [−0.369, 0.078] |

| Victim Substance Use with BSB | 0.292 | 0.097 | [0.102, 0.478]* |

| Victim Substance Use with RB | −0.070 | 0.126 | [−0.307, 0.193] |

| Coercion Severity with Perpetrator Type | −0.011 | 0.030 | [−0.070, 0.050] |

| Coercion Severity with Acknowledgment | 0.573 | 0.081 | [0.402, 0.717]* |

| Coercion Severity with BSB | −0.022 | 0.084 | [−0.195, 0.135] |

| Coercion Severity with RB | 0.287 | 0.097 | [0.092, 0.474]* |

| Variances | |||

| Perpetrator Type | 0.183 | 0.015 | [0.152, 0.211]* |

| Coercion Severity | 1.265 | 0.065 | [1.141, 1.393]* |

| Total Indirect Effects | |||

| Perpetrator Type → Acknowledgment → BSB | −0.402 | 0.165 | [−0.780, −0.135]* |

| Perpetrator Type → Acknowledgment → RB | −0.684 | 0.305 | [−1.373, −0.193]* |

Note: SE = Standard Error, CI = Confidence Interval, BSB = Behavioral Self-Blame, RB = Rapist Blame.

95% Confidence Intervals do not include zero

Figure 1.

Structural equation model with unstandardized parameter estimates displayed. Victim substance use and coercion severity were allowed to covary with each variable and are not shown here. Covariances, variances, and standard errors not depicted here are shown in Table 2.

*95% Confidence Intervals do not include zero

With regard to the indirect effects of perpetrator type on blame attributions through rape acknowledgment, the indirect effects for both Behavioral Self-Blame (b = −0.402, SE = 0.165, 95% CI: −0.780, −0.135) and Rapist Blame (b = −0.684, SE = 0.305, 95% CI: −1.373, −0.193) were present (in support of Hypotheses 4a and 4b). Compared to women who experienced a rape by a non-intimate partner, women who experienced rape in the context of a marital or dating relationship were less likely to blame themselves or the perpetrator for the assault, in part because they were less likely to label their experience as a rape (even when controlling for victim substance use and coercing severity). Moreover, the reverse causality model was not supported, as the indirect effect of perpetrator type on rape acknowledgment through Behavioral Self-Blame and Rapist Blame was absent (b = −0.131, SE = 0.074, 95% CI: −1.012, 0.045). This suggests that although blame and acknowledgment were assessed at the same time, the relation of perpetrator type on blame attributions is indirect through rape acknowledgment (as hypothesized), instead of the reverse.

Discussion

The present study examined differences in blame attributions and rape acknowledgment (as well as their interrelations) as a function of perpetrator type. Overall, findings revealed the presence of indirect effects of perpetrator type on both self- and perpetrator blame through rape acknowledgment, when controlling for victim substance use and coercion severity. Specifically, compared with victims of rape by a non-intimate partner, women who experienced rape by an intimate partner were less likely to acknowledge the assault as rape and in turn, reported lower levels of self- and perpetrator blame. These findings are discussed in detail below.

Consistent with prior work (Bergen, 1996; Finkelhor & Yllo, 1982; Frieze, 1983), IPR victims reported moderate levels of behavioral self-blame (mean of 2.52 on a scale of 1 to 5). However, in support of our first hypothesis, victims of IPR reported less behavioral self-blame than victims of rape by any other perpetrator (mean of 3.65). Due to the nature of intimate relationships and inherent assumptions about safety of actions around intimate partners, victims of IPR may be less likely to identify their own behaviors prior to an assault as blameworthy or contributing to the risk of being sexually assaulted than victims of rape by other perpetrators. By contrast, women who experienced IPR did not differ from women who were raped by a non-intimate partner in attributions of perpetrator blame—even when controlling for victim substance use and coercion severity. Although contrary to expectations, this result is consistent with a recent study showing that the victim’s level of acquaintance with the perpetrator (i.e., how well she knew the perpetrator prior to the assault) was unrelated to perpetrator blame when controlling for other characteristics of the assault (Donde, 2015). Although there was not a direct relationship between perpetrator type and perpetrator blame in this study, findings suggest that rape acknowledgment may play a key role in this association.

Women who reported IPR were less likely than women who reported rape by another perpetrator to label their victimization experiences as a rape. This finding is consistent with our hypotheses as well as prior research suggesting that compared with other victims, women who are sexually victimized by an intimate partner are less likely to label their experience as rape (Cleere & Lynn, 2013; Kahn et al., 2003; Koss, 1985). Difficulties acknowledging IPR as rape may arise to some degree because sexual assault committed by an intimate partner deviates from conventional rape scripts that place a heavy emphasis on stranger-perpetrated assault (Logan et al., 2015; Turchik et al., 2007). This finding is also consistent with the notion that acknowledgment of IPR may produce cognitive dissonance given that someone to whom the victim is strongly committed has perpetrated such a serious violation. Reframing the experience as something more acceptable than rape may be a way for victims of IPR to increase consistency between their beliefs (i.e., sexual assault is unacceptable) and a desire to remain in the relationship. Consistent with this possibility, Harned (2005) surveyed college women who had an unwanted sexual experience with a dating partner and found that none of the women who labeled their experience as a sexual assault remained in the relationship, whereas one in four women who did not label their experience as an assault remained with their partner. Moreover, although Littleton, Axsom, and Grills-Taquechel (2009) found no differences in rape acknowledgment based on a history of a romantic relationship with the perpetrator, sexual assault victims who continued their relationship with the perpetrator were less likely to acknowledge this experience as rape.

Consistent with recent research in large college samples (Bondurant, 2001; Orchowski et al., 2013), women who did not label their experience as rape reported less self-blame than those who identified their experience as rape. This suggests that some degree of rape acknowledgment may be necessary for victims to assign self-blame. Prior research also indicates that women who label their experiences as rape report more perpetrator blame (Botta & Pingree, 1997; Cleere & Lynn, 2013; Kahn et al., 2003; Orchowski et al., 2013). The current results add to those findings and lend further support to the notion that women are more likely to hold a perpetrator accountable for his actions when they perceive the experience to be rape. Moreover, although prior studies on self- and perpetrator blame have relied primarily on convenience samples of college women, the current study extends these findings by documenting similar relations in a diverse sample of community women.

Finally, results supported our prediction that the relation of perpetrator type to blame attributions would be indirect through rape acknowledgment. As discussed above, compared with victims of rape by any other perpetrator, women who experience IPR may be less likely to label their experience as rape, resulting in fewer attributions of blame. Although past qualitative work has suggested a reverse model in which initial blame for an assault predicts later acknowledgment of the event as a rape (e.g., Harned, 2005; Pitts & Schwartz, 1993), our analyses examining the indirect effect of perpetrator type on rape acknowledgment through blame attributions did not support this alternate model.

Limitations

Limitations of the present study suggest several directions for future research. First, although our data support the existence of an indirect relation of perpetrator type to blame attributions through rape acknowledgment, the cross-sectional design does not permit conclusions about the precise nature or temporal order of the observed relations. Longitudinal research is needed to clarify temporal associations and examine whether perceptions and acknowledgment of sexual assault change over time (Littleton, Rhatigan, & Axsom, 2007). Although attributions were only assessed with regard to one index assault in the current study, prospective studies may help to disentangle the influence of multiple assaults (perpetrated by both partners and non-partners) on acknowledgment and blame attributions. In this study, participants with multiple assaults reported on only the assault they identified as most distressing; thus, it is possible that participants may have been more likely to select and report on particular types of assaults (e.g., by non-intimate partners). Other strategies for selecting an index assault (e.g., most recent assault) might yield different findings and should be examined in future work.

Second, our definition of “intimate partner” included only spouses and current steady dating partners; thus, this definition excluded some types of partners (e.g., former dating partners, casual sex partners) and did not make distinctions among current intimate partners (e.g., married, cohabitating). Consistent with script theory, rape acknowledgment (and, thus, blame attributions) may vary by level of commitment to the perpetrator. For example, sexual assaults within married couples may deviate more significantly from typical scripts than do assaults within casual sexual partnerships (Littleton, Rhatigan, & Axsom, 2007). Future studies should consider the role of these relationship characteristics in victims’ perceptions of sexual assault.

Third, although the present study extends past work using convenience samples of college women by including community women from four locations across the U.S. and a substantial number of ethnic and sexual minorities, the generalizability of the current findings is still limited in several ways. First, only eight IPR victims acknowledged their assault as rape, so it is difficult to know whether their experience is representative of others who acknowledge being raped by an intimate partner. Second, prior research has suggested that the sexual orientation of the victim may impact third-party individuals’ blame attributions (Wakelin & Long, 2003). Although not a focus of the current study, future research should examine whether the associations among perpetrator type, rape acknowledgment, and victims’ blame attributions differ as a function of sexual orientation. Finally, this study focused on only perpetration by male partners. Although men perpetrate the vast majority of sexual assaults (99%; Greenfeld, 1997), victim attributions for assaults perpetrated by women is an important area for future study.

Research Implications

Although this study assessed only behavioral self-blame and perpetrator blame, victims may attribute responsibility for the assault to other factors. For example, instead of finding fault in their specific actions or behaviors, rape victims may attribute blame to aspects of their personality (e.g., being too trusting or impulsive), known as characterological self-blame (Janoff-Bulman, 1979). Victims may also blame the society at large (e.g., “the rape culture,” the power of men in society; Branscombe et al., 2003), unique aspects of the situation (e.g., the perpetrator being under extreme stress), or other individuals (e.g., peers who may have egged on the perpetrator, bystanders who did not assist). Although not assessed in the current study, future research should examine additional aspects of blame attributions. Findings of low levels of characterological, societal, situational, and other blame attributions among victims who do not label their experience as rape would further support our conjecture that victims labeling a sexual experience as a rape is necessary for the event to be considered blameworthy.

Clinical Implications

The present findings have several implications for clinicians who encounter victims of rape—particularly rape committed by an intimate partner—in their practice. First, we found that approximately four of five IPR victims did not label their experience as rape. This suggests that behaviorally-specific questions (vs. asking more broadly about experiences of “rape” or “sexual assault”) may be needed to accurately assess a client’s sexual victimization history. Moreover, there may be utility in assessing unique aspects of intimate partner sexual assault (e.g., forced pornographic acts, sexual acts with other individuals) that current measures of sexual assault and intimate partner violence do not assess (Bagwell-Gray, Messing, & Baldwin-White, 2015; Moreau, Boucher, Hébert, & Lemelin, 2015). For clients who do report experiences of IPR or sexual assault, psychoeducation may be helpful in combating preconceived notions of rape or societal rape scripts. Such psychoeducation, especially when provided in a group setting, may convey that victims are not alone and not to blame (Kelly & Stermac, 2012).

Furthermore, although additional research is needed to better understand the implications of rape acknowledgment and blame attributions for victims’ psychological functioning, preliminary evidence suggests that victims of unacknowledged (vs. acknowledged) sexual assaults have poorer risk recognition (Marx & Soler-Baillo, 2005) and are more likely to continue a relationship with their perpetrator and report subsequent sexual victimization experiences (Littleton et al., 2009). Given this potential risk for revictimization, clinicians working with victims of unacknowledged IPR should incorporate safety planning and risk assessment into treatment. Moreover, in cases where behavioral descriptions clearly meet the legal definition of rape, clinicians may carefully consider encouraging rape acknowledgment. Although such acknowledgment may be beneficial in reducing the risk of revictimization, the current findings suggest that such acknowledgment may also lead to increases in self-blame. Notably, however, the therapeutic setting provides an ideal context for exploring attributions of responsibility. Clinicians can draw on evidence-based interventions to address blame-related cognitions (such as Cognitive Processing Therapy; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2017) and manage blame-related distress. The findings and theory presented in this study also suggest that IPR victims may not label an experience as rape due, in part, to investment in the romantic relationship and resulting cognitive dissonance. Clinicians should therefore consider how these factors might influence clients’ reactions to the suggestion of acknowledgment. Additional research is needed to understand the process of coming to acknowledge an experience as IPR in a therapeutic context.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R01 HD062226, awarded to the third author (DD).

Footnotes

Spouse and current dating partner were combined into one “intimate partner” category because few participants identified the perpetrator as a spouse (n = 10), and those who did report assault by a spouse did not differ from those who identified the perpetrator as a current dating partner (n = 40) in self-blame, t(48) = −.214, p > .05, perpetrator blame, t(48) = .456, p > .05, or acknowledgment status, Χ2(1) = .149, p > .05.

Models with participant age and student status as additional covariates yielded the same pattern of results reported here.

Contributor Information

Anna E. Jaffe, Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Anne L. Steel, Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

David DiLillo, Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Terri L. Messman-Moore, Department of Psychology, Miami University

Kim L. Gratz, Department of Psychology, University of Toledo

References

- Ayala EE, Kotary B, & Hetz M (2015). Blame attributions of victims and perpetrators: Effects of victim gender, perpetrator gender, and relationship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260515599160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell-Gray ME, Messing JT, & Baldwin-White A (2015). Intimate partner sexual violence: A review of terms, definitions, and prevalence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16, 316–335. doi: 10.1177/1524838014557290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen RK (1996). Wife rape: Understanding the response of survivors and service providers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, & Stevens MR (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Bondurant B (2001). University women’s acknowledgment of rape. Violence Against Women, 7, 294–314. doi: 10.1177/10778010122182451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botta RA, & Pingree S (1997). Interpersonal communication and rape: Women acknowledge their assaults. Journal of Health Communication, 2, 197–212. doi: 10.1080/108107397127752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Wohl MJA, Owen S, Allison JA, & N’gbala A (2003). Counterfactual thinking, blame assignment, and well-being in rape victims. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 25, 265–273. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2504_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL, Testa M, & Messman-Moore TL (2009). Psychological consequences of sexual victimization resulting from force, incapacitation, or verbal coercion. Violence Against Women, 15, 898–919. doi: 10.1177/1077801209335491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleere C, & Lynn SJ (2013). Acknowledged versus unacknowledged sexual assault among college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 2593–2611. doi: 10.1177/0886260513479033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donde SD (2015). College women’s attributions of blame for experiences of sexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260515599659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donde SD (2016). College women’s assignment of blame versus responsibility for sexual assault experiences. Violence Against Women. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1077801216665481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2012). UCR Program changes definition of rape. The CJIS Link, 14(1), 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. California: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, & Yllo K (1982). Forced sex in marriage: A preliminary research report. Crime & Delinquency, 28, 459–478. doi: 10.1177/001112878202800306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Daigle LE, Cullen FT, & Turner MG (2003). Acknowledging sexual victimization as rape: Results from a national-level study. Justice Quarterly, 20, 535–574. doi: 10.1080/07418820300095611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, & Taylor SE (1991). Social cognition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA (1990). Victim attributions and post-rape trauma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 298–304. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.2.298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA (2003). Perceived control and distress following sexual assault: A longitudinal test of a new model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1257–1269. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, & Seales LM (1997). Acquaintance rape is real rape In Schwartz MD, Schwartz MD (Eds.), Researching sexual violence against women: Methodological and personal perspectives (pp. 54–64). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Frieze IH (1983). Investigating the causes and consequences of marital rape. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 8, 532–553. doi: 10.1086/493988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld LA (1997). Sex offenses and offenders: An analysis of data on rape and sexual assault. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb AR, & Harrower J (2009). Understanding attribution of blame in cases of rape: An analysis of participant gender, type of rape and perceived similarity to the victim. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 15, 63–81. doi: 10.1080/13552600802641649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS (2005). Understanding women’s labeling of unwanted sexual experiences with dating partners. Violence Against Women, 11, 374–413. doi: 10.1177/1077801204272240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys T (2007). Perceptions of sexual consent: The impact of relationship history and gender. Journal of Sex Research, 44, 307–315. doi: 10.1080/00224490701586706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R (1979). Characterological versus behavioral self-blame: Inquiries into depression and rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1798–1800. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn AS, Jackson J, Kully C, Badger K, & Halvorsen J (2003). Calling it rape: Differences in experiences of women who do or do not label their sexual assault as rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 27, 233–242. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.00103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, May P, Sörensen S, & DelTosta J (2010). Sexual revictimization during women’s first year of college: Self-blame and sexual refusal assertiveness as possible mechanisms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 2113–2126. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TC, & Stermac L (2012). Intimate partner sexual assault against women: Examining the impact and recommendations for clinical practice. Partner Abuse, 3, 107–122. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.1.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP (1985). The hidden rape victim: Personality, attitudinal, and situational characteristics. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 9, 193–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1985.tb00872.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, & Wisiniewski N (1987). The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 162–170. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, & Monson CM (1998). Marital rape: Is the crime taken seriously without co-occurring physical abuse? Journal of Family Violence, 13, 433–443. doi: 10.1023/A:1022831421093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Layman MJ, Gidycz CA, & Lynn SJ (1996). Unacknowledged versus acknowledged rape victims: Situational factors and posttraumatic stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Axsom D, & Grills-Taquechel A (2009). Sexual assault victims’ acknowledgment status and revictimization risk. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01472.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Breitkopf CR, & Berenson AB (2007). Rape scripts of low-income European American and Latina women. Sex Roles, 56, 509–516. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9189-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Rhatigan DL, & Axsom D (2007). Unacknowledged rape: How much do we know about the hidden rape victim? Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 14, 57–74. doi: 10.1300/J146v14n04_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Walker R, & Cole J (2015). Silenced suffering: The need for a better understanding of partner sexual violence. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 16, 111–135. doi: 10.1177/1524838013517560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy RJ, Nurius PS, & Norris J (2006). Responding in their best interests: Contextualizing women’s coping with acquaintance sexual aggression. Violence Against Women, 12, 478–500. doi: 10.1177/1077801206288104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy RJ, Nurius PS, & Norris J (2007). Latent profiles among sexual assault survivors: Implications for defensive coping and resistance. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22, 543–565. doi: 10.1177/0886260506298841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, & Soler-Baillo JM (2005). The relationships among risk recognition, autonomic and self-reported arousal, and posttraumatic stress symptomatology in acknowledged and unacknowledged victims of sexual assault. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 618–624. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000171809.12117.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Walsh K, & DiLillo D (2010). Emotion dysregulation and risky sexual behavior in revictimization. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34, 967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AK, Markman KD, & Handley IM (2007). Self-blame among sexual assault victims prospectively predicts revictimization: A perceived sociolegal context model of risk. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 129–136. doi: 10.1080/01973530701331585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, & Binderup T (2000). Does ‘no’ really mean ‘no’ after you say ‘yes’? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 1156–1174. doi: 10.1177/088626000015011003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau C, Boucher S, Hébert M, & Lemelin J (2015). Capturing sexual violence experiences among battered women using the revised Sexual Experiences Survey and the revised Conflict Tactics Scales. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 223–231. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0345-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, & Heppner MJ (1999). Contextualizing rape: Reviewing sequelae and proposing a culturally inclusive ecological model of sexual assault recovery. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 8, 41–62. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(99)80010-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orchowski LM, Untied AS, & Gidycz CA (2013). Factors associated with college women’s labeling of sexual victimization. Violence and Victims, 28, 940–958. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perilloux C, Duntley JD, & Buss DM (2014). Blame attribution in sexual victimization. Personality and Individual Differences, 63, 81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peter-Hagene LC, & Ullman SE (2014). Social reactions to sexual assault disclosure and problem drinking: Mediating effects of perceived control and PTSD. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 1418–1437. doi: 10.1177/0886260513507137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts VL, & Schwartz MD (1993). Promoting self-blame in hidden rape cases. Humanity and Society, 17, 383–398. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Monson CM, & Chard KM (2017). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurvinsdottir R, & Ullman SE (2015). Social reactions, self-blame, and problem drinking in adult sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Violence, 5, 192–198. doi: 10.1037/a0036316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, & Livingston JA (2007). Prospective prediction of women’s sexual victimization by intimate and nonintimate male perpetrators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 52–60. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchik JA, Probst DR, Chau M, Nigoff A, & Gidycz CA (2007). Factors predicting the type of tactics used to resist sexual assault: A prospective study of college women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 605–614. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanZile-Tamsen C, Testa M, & Livingston JA (2005). The impact of sexual assault history and relationship context on appraisal of and responses to acquaintance sexual assault risk. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 813–832. doi: 10.1177/0886260505276071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin A, & Long KM (2003). Effects of victim gender and sexuality on attributions of blame to rape victims. Sex Roles, 49, 477–487. doi: 10.1023/A:1025876522024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CA (1995). Attitudes toward rape: Feminist and social psychological perspectives. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting JB, Oka M, & Fife ST (2012). Appraisal distortions and intimate partner violence: Gender, power, and interaction. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 38, 133–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LC, & Miller KE (2016). Meta-analysis of the prevalence of unacknowledged rape. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17, 149–159. doi: 10.1177/1524838015576391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]