Abstract

The potency of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for tissue repair and regeneration is mainly based on their ability to secret beneficial molecules. Administration of MSCs has been proposed as an innovative approach and is proved by a number of clinical trials to a certain degree for the therapy of many diseases including Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, the efficacy of MSCs alone is not significant. We investigated the effect of neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase 1 (NTRK1) overexpressed peripheral blood MSCs (PB-MSCs) on PD rat model. NTRK1 was overexpressed in PB-MSCs, which were then injected into PD rat model, Dopaminergic (DA) neuron regeneration and rotational performance was assessed. We found that DA neuron repair was increased in lesion site, rotational performance was also improved in MSC transplanted PD rat, with most potent effect in NTRK1 overexpressed PB-MSC transplanted PD rat. Our results indicate that overexpression of NTRK1 in MSCs could be an optimized therapeutic way via MSCs for PD treatment.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cell, Parkinson’s disease (PD), Neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase 1 (NTRK1), Dopaminergic (DA) neuron, Regenerative therapy

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are being widely used in clinical trial since 1995 (Lazarus et al. 1995; Salehi et al. 2017). They have three cellular properties: (1) adherence, (2) CD73+ CD90+ CD105+, and CD14− CD34− CD45− CD19− HLA class II−, (3) pluripotent for mesenchymal lineages including osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocyte (Dominici et al. 2006). Administration of MSCs has been proposed as an innovative approach and is proved by a number of clinical trials to a certain degree for the therapy of many diseases, which are incurable by current treatment, including heart disease, neuron degenerative diseases, hematologic malignancies, autoimmune diseases, etc. (Peired et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016; Yi et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2016). The mechanism of MSCs therapy is also widely studied for regenerative therapy (Ikebe and Suzuki 2014; Mahmood et al. 2004; Meseguer-Olmo et al. 2017).

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the neuron degenerative diseases that could be treated by MSC therapy (Gugliandolo et al. 2016). PD is clinically characterized by a progressive degeneration of dopaminergic (DA) neurons (Beitz 2014). It is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease worldwide. PD patients develop several motor complications including rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. PD rat model that exhibits DA neuron degeneration is a useful model to study PD disease and its therapy (Gugliandolo et al. 2016). MSCs have been injected to PD rat model to assess the effect on DA neurons (Teixeira et al. 2017). However, the efficacy of MSCs alone is not significant.

It is of great interest in medical science research to promote the efficacy of MSC therapy. As MSC-mediated therapeutic benefit are mainly due to their secretome, the bioactive molecules (Gao et al. 2016). Among which neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase 1 (NTRK1) is found to promote cell differentiation and may play a role in specifying sensory neuron subtypes (Wang et al. 2015). It is also required for binding of nerve growth factor (NGF), thus NTRK1 is very important for nerve growth. Furthermore, it activates ERK1 by either SHC1- or PLC-gamma-1-dependent signaling pathway. There is report that elevated NTRK1 expression increases differentiation of neuron stem cell into cholinergic neurons under stimulation of NGF (Wang et al. 2015). For PD, NTRK1 could be one of the molecule candidates that can be released from transplanted MSCs to nearby neuron stem cells, thus can promote neuron stem cell differentiation into certain neuron type, such as DA neuron in substantia nigra (SN) in PD rat.

In this experiment we investigated the effect of NTRK1 overexpressed peripheral blood MSCs (PB-MSCs) on PD rat model. By overexpressing NTRK1 in PB-MSCs, which were then injected into PD rat model, we showed that DA neuron repair was increased in lesion site, rotational performance was also improved. Our results indicated that overexpression of NTRK1 in MSCs could be an optimized therapeutic way via MSCs for PD treatment.

Methods and materials

PBMSC isolation and culture

The experiments to use PB derived stem cell were conducted following the ethic approval from Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University. Isolation and culture of PB-MSCs were described before (Chong et al. 2012). PB from 5 healthy individuals were collected via venipuncture (through the veins in the upper limb) and collected into vacuum blood collection tubes (EDTA K2). 3 ml Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM (Amersham Biosciences, Sweden) were put into a 15 ml centrifuge tube. An equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco, NY, USA) was added into the vacuum PB collection tubes. The diluted mixture of specimen was slowly layered on top of the Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM. The centrifuge tube was then centrifuged for 25 min at 2500 rpm. The mononuclear cells were extracted and transferred into a new 15 ml centrifuge tube. Cells were washed with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s low glucose (DMEM) (Gibco, USA) with 1:1 dilution and underwent centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 10 min. Cell pellet formed at the bottom were PB mononuclear cell (PBMC) mixture containing PB-MSCs, they were resuspended using 1 ml warm fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, USA) followed by regular MSC culture.

Suspension of PBMSCs was then cultured in DMEM (20% FBS, 1% antibiotic–antimycotic (Gibco, USA). Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 5–7 days suspended cells were discarded and adherent cells were left to grow on the flask. Culture medium was changed every 3 days.

Flow cytometry analysis

MSCs were harvested and stained with CD34-FITC, CD45-PE, CD29-APC, and CD105-PE-Cy7 (BD Bioscience, CA, USA), using standard FACS procedure as described by the manufacturer.

Plasmid construction and adenovirus infection

NTRK1cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using oligo (dT) primer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The NTRK1 gene was amplified by PCR using primers: 5′-ataactataacggtcatgctgcgaggcggacggcgc-3′ and 5′-attacctctttctccctagcccaggacatccaggtag-3′.

The amplified NTRK1 gene was then cloned into plasmid vector pAdenoX-CMV using In-Fusion HD cloning kit according to manufacturer’s protocol (Clontech, USA). The adenoviruses expressing NTRK1 were prepared using Adeno-X Adenoviral System 3 (Clontech, USA). Briefly, pAdenoX-CMV-NTRK1 plasmids were linearized by PacI digestion and then transfected into Adeno-X 293 cells. The titration of constructed adenoviruses was then determined by Adeno-X Rapid Titer Kit. MSCs were exposed to adenoviruses at a MOI of 50 for 2 h at 37 °C in serum-free medium. Cells were then washed and cultured in regular culture medium.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated using ALLPrep™ DNA/RNA/Protein (Qiagen, Valencia, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The assessment of RNA integrity and concentration were checked using the experion™ RNA StdSens Analysis Kit and Experion™ automated electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Subsequently, total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA, using SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase (Gibco, USA) with Oligo (dT)18 as a primer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplified cDNA was used for RT-PCR using Advantage™ (Clontech, USA). RT-PCR was performed using the following oligonucleotides and PCR conditions: 2 min at 95 °C, (20 s at 95 °C, 20 s at the annealing temperature, and 30 s at 72 °C) ×35, and 10 min at 72 °C. GAPDH was included as a RT-PCR internal control. Reaction products were analyzed in Experion™ DNA 1 K Analysis Kit and Experion™ automated electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Primers were as follows:

NTRK1: Forward primer 5′-GGACAACCCTTTCGAGTTCA-3′; Reverse primer 5′-GTGGTGAACACAGGCATCAC-3′

GAPDH: Forward primer 5′-AATCCCATCACCATCTTCCA-3′; Reverse primer 5′-TGTGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCA-3′.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer (pH 7.4, 50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.25% deoxycholic acid, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail and 1% DTT) for 15 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min. Loading buffer was added and proteins were boiled for 5 min, followed by resolution by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk at room temperature for 1 h, the membrane was incubated with diluted primary antibodies (Abcam, MA, USA) against NTRK1 and GAPDH. The blots were incubated after wash with secondary antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Inc., USA). Immunoblots were developed using bromochloroindolyl/phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium solution (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Inc., USA).

PD rat models and rotation test

PD rat models were prepared as previous described (Chen et al. 2017). Briefly, male Sprague–Dawley rats were anesthetized and injected with 16 μg 6-OHDA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) into the right SN, and right MFB according to the Paxinos and Watson rat brain stereotaxic atlas. 6-OHDA induced lesion was tested by apomorphine (APO)-induced rotation 2 weeks after the injection.

The behavior of treated rats in response to APO (0.5 mg/kg, Sigma, USA) was assessed and only those rats showing 7 or more rotations/min during a 30-min period toward the contralateral side after APO treatment were considered successful PD rat models and used for experiments. The efficacy of transplantation on PD rat behavior was also tested at various time points after MSC transplantation.

PB-MSC transplantation

Transplantation was done as previously described (Chen et al. 2017). PD rats were randomly grouped 1 week after APO intraperitoneal injection. Rats were injected with MSCs (3 × 104 µl) into the SN of the 6-OHDA-injected (lesion) side at one point (2 µl/point). Serum-free medium was used for sham-grafted group.

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence detection

Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining was performed as described before (Chen et al. 2017). Free-floating sections (40 µm) of SN and striatum were stained with mouse anti TH antibodies (1:1000, Sigma, USA), and visualized with FITC-labeled secondary antibody or DAB (Abcam, USA).

ELISA

TNF-α and IL-1β production from the lesion area were quantified using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems Inc., USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The protein concentration in tissue homogenate was determined by using protein assay dye (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA).

Statistic analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using one or two-way ANOVA analysis following a Tukey’s post hoc test. Data were presented as mean ± SD. The significance value was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Characterization of human PB-MSCs

MSCs from peripheral blood were isolated from 5 healthy donors followed by maintain in appropriate culture condition that keep the characters of MSCs. CD34, CD45, CD29 and CD105 were used as markers for MSCs (Deans and Moseley 2000). After plating for 72 h, the adhered cells exhibited a fusiform or polygonal shape as distinguished for MSCs. Cells then were stained for MSC markers and analyzed by Flow cytometry. They were identified as MSCs rather than hematopoietic stem cells based on the phenotype of MSCs showed in Fig. 1: CD34− CD45− CD29+ CD105+. These data indicated that we have successfully isolated MSCs from peripheral blood.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of human PBMSCs. Flow cytometric analysis reveals that PBMSCs were positive for CD105 and CD29, but negative for CD34 and CD45

Overexpression of NTRK1 in PB-MSC

Next we want to overexpress NTRK1 in PB-MSCs. Adenovirus transfection method successfully transfected MSC with NTRK1, along with an empty vector transfected control, as shown in Fig. 2a. The level of gene expression and protein expression were measured using RT-PCR and western blot, respectively. NTRK1 mRNA level was significantly higher in transfected MSCs than that in control group and vector alone group. Figure 2b showed that NTRK1 expression was much higher in transfected MSC group. Protein levels were also quantified. Quantification showed it was almost 4 times higher than that in control group and vector alone group, as shown in Fig. 2c. These results confirmed that the successful transfection of NTRK1 into MSC also led elevated NTRK1 protein level.

Fig. 2.

Verification of NTRK1 over-expression in PBMSCs mediated by adenovirus vector. a Relative NTRK1 mRNA levels were examined by RT-PCR and normalized to control. GAPDH was employed as an internal control. b, c NTRK1 protein expressions were analyzed by western blotting. GAPDH was employed as a loading control. Data were shown as mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 compared to control

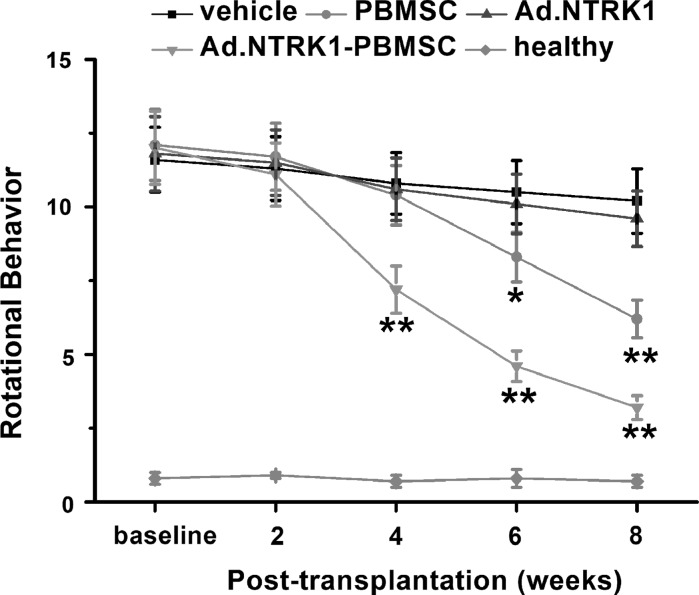

Effects of PB-MSC transplantation on behavioral changes of PD rats

MSCs with overexpression of NTRK1 were then transplanted into PD rat model to assess the effect on rotational behavior. PD rat model was established as described before using 6-hydroxidopamine (6-OHDA) (Teixeira et al. 2017). Cells were transplanted into SN via intranjgral injection. Rotational performance was tested in animals at different time points after transplantation: 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. Among the 4 groups: vehicle (serum-free culturing medium), Ad.NTRK1, PB-MSC, and Ad.NTRK1-PB-MSC, we found that the Ad.NTRK1-PB-MSC group, in which the NTRK1 was overexpressed, showed the most improved performance, followed by the PB-MSC group as shown in Fig. 3. The number of rotations of the PD rats was reduced. Ad.NTRK1-PB-MSC group showed significant decrease compared with control groups since 4 weeks. However, PB-MSC group also showed significant decrease compared with control groups since 8 weeks. The vehicle group, compared to the Ad.NTRK1 group, didn’t show much different. It is worth noting that Ad.NTRK1-PB-MSC group showed better improved performance when compared to PB-MSC group since 4 week. These results demonstrated that PB-MSC can improve behavior of PD rat model, and NTRK1 overexpression in MSC can promote this effect.

Fig. 3.

Effects of PBMSC transplantation on behavioral changes of PD rats. Rotational performance of PD rats was assessed before and after PBMSC transplantation at indicated time. Healthy rats were used as a positive control. N = 8 in each experimental group. Data were shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared to vehicle group

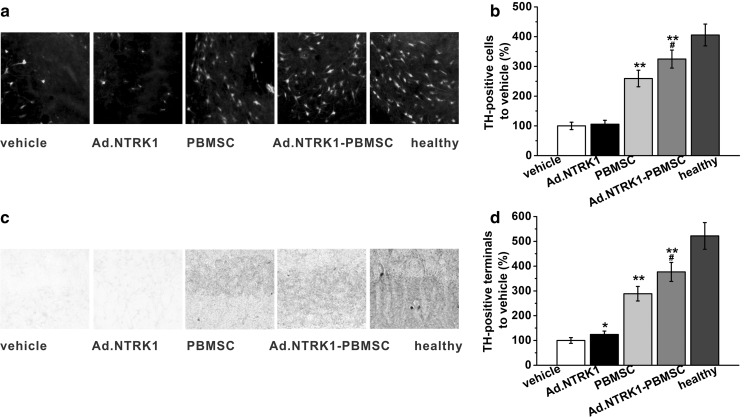

Effects of PB-MSC transplantation on dopaminergic neurons in PD rats

Neurodegeneration of DA neuron is characterized in PD. In PD rat model, 6-OHDA injection led to severe degeneration of DA neurons in the SN, as showed by TH immunostaining in Fig. 4a. The effect of MSC transplantation on DA neurons was assessed by staining of TH in the SN and striatum at 8 weeks post transplantation. Quantification of the TH positive cells in SN showed more DA neurons were found in MSC transplanted groups, almost 3 times as that as counted in vehicle group, as showed in Fig. 4b. There was not so much difference between vehicle group and Ad.NTRK1 group. However, the Ad.NTRK1-PB-MSC group showed more TH-immunoreactive cells than that found in the PBMSC group. TH-immunoreactive fibers in the striatum also showed the same trend, as showed in Fig. 4c, d. These data indicated that intranigral MSC transplantation caused significant increase of TH-immunoreactive cells in the SN, while NTRK1 overexpression PB-MSC exhibited the most potent effect, suggesting that NTRK1 overexpression could promote DA neurons regeneration in the SN in PD rats.

Fig. 4.

Effects of PBMSC transplantation on neurodegeneration of dopaminergic neurons in PD rats 8 weeks post-transplantation. a, b Dopaminergic neurons on the lesion side of the SN of the PD rats were immune stained by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). c, d TH-positive terminals in the striatum of the PD rats were visualized by immune histochemical staining. Relative TH-positive terminals were quantified by optical densities in each group and normalized to vehicle control. Healthy rats were used as a positive control. Data were shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared to vehicle group. #p < 0.05 compared to PBMSC group

Effects of PB-MSC transplantation on pro-inflammatory cytokine production in PD rats

MSCs have been noted for the ability of immunomodulatory effects in vivo. In order to see if PB-MSC transplantation will have immunomodulatory effects, we checked the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and IL-1β production in lesion area of all groups. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, compared with the cytokine level in PB-MSC transplanted group, both cytokines showed no significant change in NTRK1 overexpressed-PB-MSC transplanted group. However, these MSC transplanted groups showed a slight decrease of production for both cytokines, compared with that in control groups. These results indicated that PB-MSC had effect on cytokine production in vivo, no matter if NTRK1 was overexpressed.

Fig. 5.

Effects of PBMSC transplantation on pro-inflammatory cytokine production in the lesion area of PD rats 2 weeks post-transplantation. Pro-inflammatory cytokines included TNF-α (a) and IL-1β (b) in this study, analyzed by corresponding ELISA assays. Data were shown as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, compared to vehicle group

Discussion

Cell therapy has been widely studied in animal disease model including PD rat model. MSC transplantation is a new strategy for PD with great potential as a novel therapy. Previous study has shown that MSC transplantation has effect on PD rat model, however, here we overexpressed a critical neurotrophic factor, NTRK1, into MSC, and we found it had even better therapeutic effect based on rotation behavior and DA neurons regeneration. Our experiment pointed a new strategy that neurotrophic factors can be expressed and delivered to lesion site via MSC transplantation.

The potency of MSCs for tissue repair and regeneration is based on their ability to secret beneficial cytokines and growth factors (Moghadasali et al. 2013; Nargesi et al. 2017; Sevivas et al. 2016). Overexpression of certain molecules and growth factors targeting different disease might be a way for disease-target therapy. NTRK (also known as Trk) family is a group of membrane-bound receptors that regulating synaptic strength and plasticity in the nervous system in mammalian (Huang and Reichardt 2003). These receptors can phosphorylates itself and members of the MAPK signaling pathway, transducing signals to downstream molecules. Isoform NTRK1 is also required for binding of NGF, neurotrophin-3 and neurotrophin-4/5 but not brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). The release of NTRK1 from MSCs not only has potential to promote DA neuron regeneration, but also increases differentiation of NSCs into cholinergic neurons under stimulation of NGF (Wang et al. 2015), which will contribute to the treatment of PD. Thus overexpression of certain neurotrophic factors into MSCs and use their secretome could be an alternative strategy at current stage.

In vitro and in vivo data has shown MSCs modulate the immunological activity of different cell populations (Abdi et al. 2008; Hynes et al. 2016). MSCs can effectively inhibit proliferation of CD4 and CD8 T cells. They promote a shift in T cells from a pro-inflammatory state to an anti-inflammatory state. MSCs also affect the production of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells, which inhibit lymphocyte proliferation in allogeneic transplantation. MSC can inhibit B cell proliferation as well. Though the exact mechanisms underlying the immunomodulatory functions of MSCs remain obscure, these cells have been exploited in many clinical trials targeting autoimmune diseases such as graft-versus-host disease, Grohn’s disease (Gavioli et al. 2005).

MSCs from different source such as bone marrow and blood have been compared for their stem cell properties, yet some studies showed MSCs from peripheral blood maintain similar characteristics and have similar chondrogenic differentiation potential to those derived from BM (Chong et al. 2012). In clinical trial there is no clear guidance for the dosage of MSCs in therapeutic applications, and is largely dependent on the practitioner and upon the type of therapy. However, 1.0–2.0 × 106 MSCs/kg body weight is generally used (Schallmoser et al. 2008). The practical way to obtain sufficient number of cells is either to expand isolated MSCs in vitro or to find a good source for MSCs. However, all commercial available mediums we have tested for expanding and maintenance of MSCs can not fully meet the requirement for clinical use, thus it is also urgent to develop quality MSC culture medium of clinical grade. Meanwhile, peripheral blood is an easy access source, compared with bone marrow. Despite the invasive procedure for isolating BM-MSCs, it is also controversial if sufficient numbers of MSCs can be obtained from this source. Besides, MSCs from peripheral blood is easier to be self-transplanted. Umbilical cord matrix/blood could also be considered to be a rich, no-invasive and abundant source for MSCs (Zeddou et al. 2010).

More important, the safety issue and the convenience are still need to be considered before clinical setting for PD treatment and other diseases. Protocols for isolation and expansion of donor MSCs that might affect the efficacy and safety of the therapy should be standardized internationally. The standard should be evidence-based, of good medical practice grade, clinically practical, cost-effective, and regulatory authority-compliant (Ikebe and Suzuki 2014).

Conclusion

In order to improve the efficacy of MSCs therapy for PD treatment, we investigated the effect of NTRK1 overexpressed PB-MSCs on PD rat model. NTRK1 was overexpressed in PB-MSCs, which were then injected into PD rat model, DA neuron regeneration and rotational performance was assessed. We found that DA neuron repair was increased in lesion site, rotational performance was also improved in MSC transplanted PD rat, with most potent effect in NTRK1 overexpressed PB-MSC transplanted PD rat. Our results indicated that overexpression of NTRK1 in MSCs could be an optimized therapeutic way via MSCs for the treatment of PD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Development Plan of Shandong Medical and Health Technology (2015WS0070).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Contributor Information

Wei Zhang, Email: zhangweiydzx@163.com.

Guangming Xu, Email: xuguangmingls@163.com.

References

- Abdi R, Fiorina P, Adra CN, Atkinson M, Sayegh MH. Immunomodulation by mesenchymal stem cells: a potential therapeutic strategy for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:1759–1767. doi: 10.2337/db08-0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitz JM. Parkinson’s disease: a review. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2014;6:65–74. doi: 10.2741/S415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Fu W, Zhuang W, Lv C, Li F, Wang X. Therapeutic effects of intranigral transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells in rat models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95:907–917. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong PP, Selvaratnam L, Abbas AA, Kamarul T. Human peripheral blood derived mesenchymal stem cells demonstrate similar characteristics and chondrogenic differentiation potential to bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:634–642. doi: 10.1002/jor.21556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans RJ, Moseley AB. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology and potential clinical uses. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:875–884. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici M, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2062. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavioli M, et al. Incidence and clinical impact of sterilized disease and minimal residual disease after preoperative radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1851–1857. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugliandolo A, Bramanti P, Mazzon E. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in Parkinson’s disease animal models. Curr Res Transl Med. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.retram.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:609–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes K, Bright R, Proudman S, Haynes D, Gronthos S, Bartold M. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cell in experimental arthritis in rat and mouse models: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikebe C, Suzuki K. Mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative therapy: optimization of cell preparation protocols. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:951512. doi: 10.1155/2014/951512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus HM, et al. Phase I multicenter trial of interleukin 6 therapy after autologous bone marrow transplantation in advanced breast cancer. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1995;15:935–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood A, Lu D, Chopp M. Intravenous administration of marrow stromal cells (MSCs) increases the expression of growth factors in rat brain after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:33–39. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meseguer-Olmo L, et al. Intraarticular and intravenous administration of 99MTc-HMPAO-labeled human mesenchymal stem cells (99MTC-AH-MSCS): In vivo imaging and biodistribution. Nucl Med Biol. 2017;46:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghadasali R, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium accelerates regeneration of human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells after gentamicin toxicity. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2013;65:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargesi AA, Lerman LO, Eirin A. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for renal repair. Curr Gene Ther. 2017 doi: 10.2174/1566523217666170412110724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peired AJ, Sisti A, Romagnani P. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for kidney disease: a review of clinical evidence. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:4798639. doi: 10.1155/2016/4798639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi H, Amirpour N, Razavi S, Esfandiari E, Zavar R. Overview of retinal differentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells: a promising approach for retinal cell therapy. Ann Anat. 2017;210:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallmoser K, et al. Rapid large-scale expansion of functional mesenchymal stem cells from unmanipulated bone marrow without animal serum. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14:185–196. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevivas N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell secretome: a potential tool for the prevention of muscle degenerative changes associated with chronic rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0363546516657827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira FG, et al. Impact of the secretome of human mesenchymal stem cells on brain structure and animal behavior in a rat model of Parkinson’s Disease. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:634–646. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2016-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, He F, Zhong Z, Lv R, Xiao S, Liu Z. Overexpression of NTRK1 promotes differentiation of neural stem cells into cholinergic neurons. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:857202. doi: 10.1155/2015/857202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Wang S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and cell therapy for bone repair. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2016;9:289–299. doi: 10.2174/1874467208666150928153758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi HG, et al. Allogeneic clonal mesenchymal stem cell therapy for refractory graft-versus-host disease to standard treatment: a phase I study. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20:63–67. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeddou M, et al. The umbilical cord matrix is a better source of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) than the umbilical cord blood. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:693–701. doi: 10.1042/CBI20090414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Huang F, Chen Y, Qian X, Zheng SG. Progress and prospect of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy in atherosclerosis. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:4017–4024. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]