Abstract

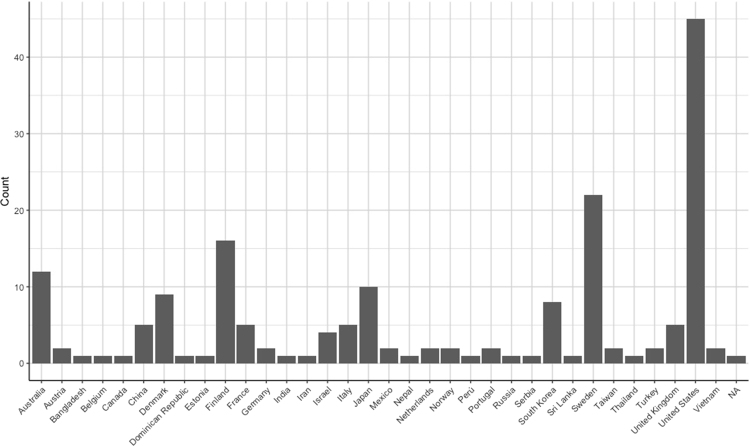

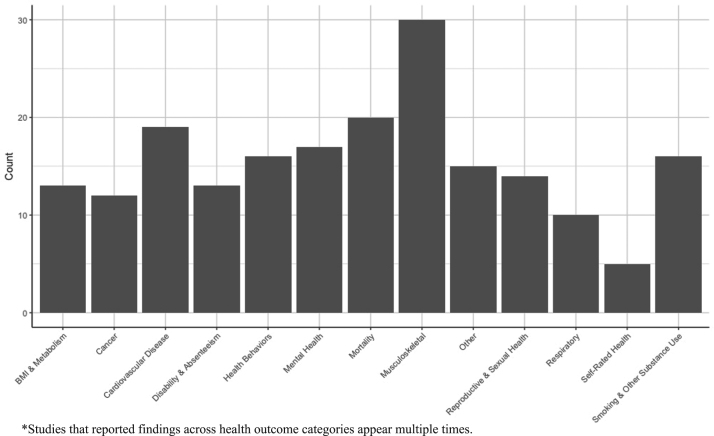

Despite the implications of gender and sex differences for health risks associated with blue-collar work, adverse health outcomes among blue-collar workers has been most frequently studied among men. The present study provides a “state-of-the-field” systematic review of the empiric evidence published on blue-collar women's health. We systematically reviewed literature related to the health of blue-collar women published between January 1, 1990 and December 31, 2015. We limited our review to peer-reviewed studies published in the English language on the health or health behaviors of women who were presently working or had previously worked in a blue-collar job. Studies were eligible for inclusion regardless of the number, age, or geographic region of blue-collar women in the study sample. We retained 177 studies that considered a wide range of health outcomes in study populations from 40 different countries. Overall, these studies suggested inferior health among female blue-collar workers as compared with either blue-collar males or other women. However, we noted several methodological limitations in addition to heterogeneity in study context and design, which inhibited comparison of results across publications. Methodological limitations of the extant literature, alongside the rapidly changing nature of women in the workplace, motivate further study on the health of blue-collar women. Efforts to identify specific mechanisms by which blue-collar work predisposes women to adverse health may be particularly valuable in informing future workplace-based and policy-level interventions.

Keywords: Women's health, Occupational health, Blue-collar, Systematic review

Highlights

-

•

Risks associated with blue-collar jobs are largely studied among men.

-

•

We present a state-of-the-field review of the extant literature on blue-collar women's health

-

•

Our findings span a quarter century, forty countries, and thirteen types of health outcome.

-

•

We find inferior health among blue-collar women, with notable heterogeneity across studies.

1. Introduction

The term “blue-collar work” is frequently used to describe working class jobs that require manual labor. These jobs are often both physically and psychologically demanding, and have been linked with various adverse health outcomes. Evidence suggests, however, that men's and women's exposures and health outcomes in blue-collar jobs may vary considerably. Differences in mortality are consistently noted between men and women in the general population, whereby women outlive men in almost every country in the world and with lower mortality rates observed among women throughout the lifecourse (Åkerstedt et al., 2004, Aittomäki et al., 2003, Ahlgren et al., 2012). Yet women on average exhibit higher rates of morbidity, report inferior self-rated health, and use more health services as compared with men (Case and Paxson, 2005).

Theories explaining the “gender paradox” in morbidity and mortality suggest that biological characteristics and social pressures operating across the lifecourse—both independently and synergistically—contribute to inequalities in men and women's health (Andrés et al., 2010, Ahlgren et al., 2012). Within the context of the relationship between work and health, differences in biological susceptibility to workplace hazards can result from differences in toxicokinetic responses (i.e., absorption, metabolism, and excretion) to occupational chemicals, dust, and other hazardous substances (Arbuckle, 2006). The consequences of nontraditional work hours (e.g., swing shifts, night shifts) can also manifest differently in men and women due to differences in circadian rhythms (Santhi et al., 2016). Lastly, anthropometric differences between men and women can mediate the effects of blue-collar work on health risks: spaces, equipment, and tools that are optimized for the average male worker may be ill-suited for female workers (Arena et al., 1999, Arnold and Bongiovi, 2012, Arbuckle, 2006).

Non-biological differences in susceptibility to health risks include behavioral differences, such as in smoking habits, diet, and use of medications, as well as differences in psychosocial stressors. Women in blue-collar workplaces, for example, are especially vulnerable to experiencing gender discrimination, sexual harassment, social isolation, and work-life conflict (Asztalos et al., 2009, Bakirci et al., 2007, Baigi et al., 2001, Bennett et al., 2007, Berman et al., 1994, Baigi et al., 2002, Bentley et al., 2008).

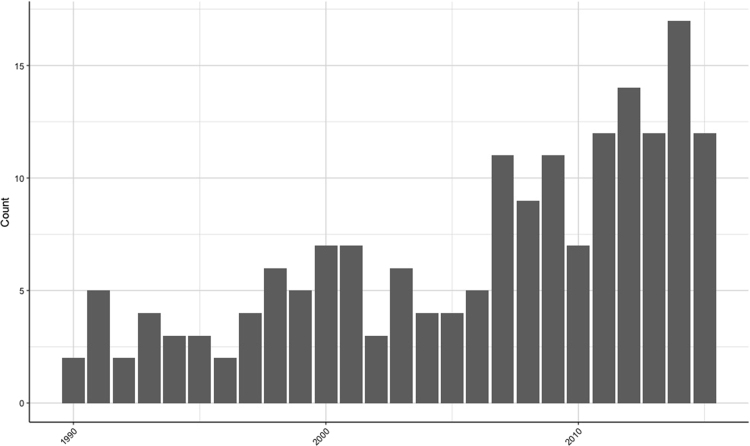

Despite the implications of gender and sex differences for health risks associated with blue-collar work, adverse health outcomes among blue-collar workers has been most frequently studied among men (Asztalos et al., 2009, Biron et al., 2011, Betenia et al., 2012). The present study provides a “state-of-the-field” systematic review of the empiric evidence published on blue-collar women's health from 1990 to 2015. This 25-year period captures major trends in the global economy that may be salient to the health and well-being of contemporary working women, including industry deregulation, computerization and automation of working-class jobs, union decline and weakened institutional protections for workers, and the rise in production in lower income countries (Björkstén et al., 2001, Blue, 1993, von Bonsdorff et al., 2011, von Bonsdorff et al., 2012, Del Bono et al., 2012).

Our specific objectives were to assess: the extent and strength of the existing empiric evidence on the health of blue-collar women; discernable patterns in publication over time, across countries, and among various health outcomes; and the degree to which study findings converge. Our review includes studies that evaluated specific risk factors for morbidity and mortality among blue-collar women, as well as studies that compared the health of blue-collar women with women in other industries or men in blue-collar jobs. Although we provide some analysis of the studies by place, time, and health outcome, differences in study design and specific exposures/outcomes studied inhibited us from offering a quantitative synthesis of the direction and magnitude of associations between work and health. We discuss instead general trends and themes, as well as general methodological limitations of the extant literature. We conclude with future directions for research.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Identification of papers

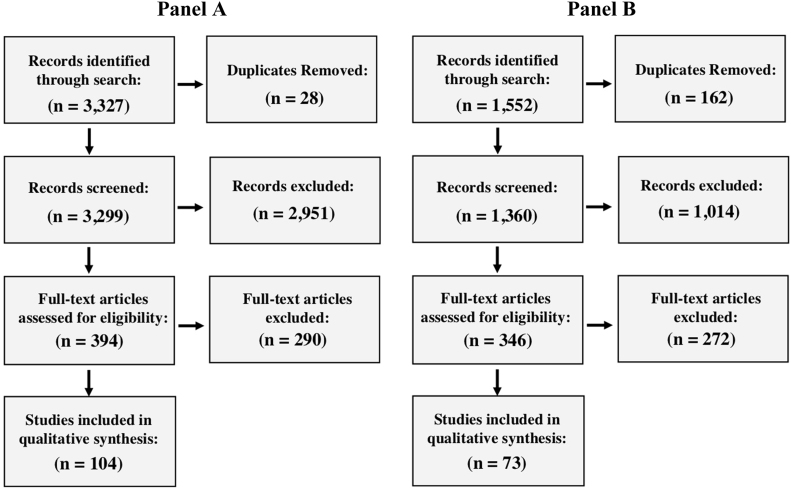

In the present study, we systematically reviewed the peer-reviewed literature related to the health of blue-collar women published between January 1, 1990 and December 31, 2015. We conducted our preliminary search across three major research databases (Google Scholar, Web of Science, and PubMed) for literature relevant to blue-collar women's health, using combinations of the terms “blue-collar,” “health,” and “women” or “female.”

We subsequently employed a second, more flexible, targeted search strategy among these same three databases that integrated synonyms and related terms (e.g. MeSH terms). We additionally expanded our second search to incorporate findings from several smaller research databases from the biomedical, social science, and humanities fields, including: Medline (PubMed), Scopus (Elsevier), Gender Watch (ProQuest), Social Sciences Citation Index (Clarivate), LGBT Life Full Text (EBSCO), CINAHL (EBSCO), Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews (Cochrane), SafetyLit (SafetyLit Foundation), and Women's Studies Quarterly. Search algorithms were developed specifically for each database by a medical librarian. A complete list of search terms used for identification of papers is provided in Appendix A.

2.2. Selection criteria

We initially identified articles for full-text review based on the contents of the abstract. Studies were deemed eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: the study was peer-reviewed and published in the English language; the dependent variable was a health outcome or health behavior (e.g., diet, physical activity, smoking and other substance use); the study population included women who were presently working or had previously worked in a blue-collar job; and the results included a multivariate-adjusted point estimates specific to female blue-collar workers. We defined blue-collar work, consistent with the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, to include precision production, craft, and repair occupations; machine operators and inspectors; transportation and moving occupations; and handlers, equipment cleaners, helpers, and laborers (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). Studies were eligible for inclusion regardless of the number, age, or geographic region of blue-collar women in the study sample.

Studies were excluded if there was no empirical quantitative analysis (i.e. qualitative research), if only descriptive and summary statistics were presented (i.e. not multivariate adjusted), if they were not peer reviewed, or if the outcome was deemed unrelated to health. We additionally excluded studies that included blue-collar women in the overall study population but failed to specify results or an exposure unique to blue-collar women. Lastly, we excluded those studies for which we were unable to discern whether blue-collar women were grouped with office and clerical workers in their analyses (Brown et al., 2017, Bromet et al., 1992).

2.3. Data extraction

Two researchers independently assessed and extracted data from the selected articles. The first researcher examined studies published between 1990 and 2002 (A.F.), while the second examined studies published between 2003 and 2015 (H.E.). The researchers cross-checked a random subset of each other's studies in order to ensure that selection criteria were consistently and accurately applied.

We extracted and recorded the following study characteristics from each study: study author(s) and year of publication; title; country of the study subjects; years over which study data were collected; sample size, number of women, and number of blue-collar women; industry subsector; study design (cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control, or quasi-experimental); independent variable(s); specific health outcome(s); the referent group (i.e., to whom authors compared blue-collar women); a summary of the study's main findings; a brief description of the study population; and country classification.

We classified the country of origin for study subjects as high-, middle- or low-income based on World Bank Country and Lending Groups classification (World Bank, 2018). We classified industry subsector based on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Where insufficient detail was provided to identify industry subsector, we list the industry supersector (e.g., manufacturing). If five or more industry subsectors were represented in the study population or if the study was population-based, we specified “Multiple Industries.” (US Census Bureau, 2017) For a subset of studies that compared the health of male and female blue-collar workers, gender was not considered as a main effect. Similarly, for a subset of studies that compared the health of blue-collar women and women in other industries or job types, occupational class was not considered as a main effect. We use superscripts in the “referent group” column in Table 2 to identify these papers, and we also note which papers were exploratory in nature and considered several independent variables simultaneously.

Table 2.

Empirical studies of blue-collar women's health, organized by health outcome category (n = 177)*.

| Outcome Category | Author (Year) | Title | Country | Years Observed | Sample Size (N) | Women (N) | Blue-Collar Women (N) | Industry Subsector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI & metabolism | Melamed et al. (1995) | Objective and subjective work monotony: effects on job satisfaction, psychological distress, and absenteeism in blue-collar workers | Israel | 1985–1987 | 1278 | 393 | 393 | Manufacturing |

| Nakamura, Nakamura, and Tanaka (2000) | Increased risk of coronary heart disease in Japanese blue-collar workers | Japan | 1993 | 1145 | 492 | 492 | Computer and Electronic Product Manufacturing | |

| Santos and Barros (2003) | Prevalence and determinants of obesity in an urban sample of Portuguese adults | Portugal | NR | 1424 | 868 | 254 | Multiple Industries | |

| Maty et al. (2005) | Education, income, occupation, and the 34-year incidence (1965 -99) of Type 2 diabetes in the Alameda County Study | United States | 1965–1999 | 6147 | 3293 | 417 | Multiple Industries | |

| Bennett, Wolin, and James (2007) | Lifecourse socioeconomic position and weight change among Blacks: the Pitt County Study | United States | 1988–2001 | 1167 | 751 | 573 | Multiple Industries | |

| Forman-Hoffman et al. (2008) | Retirement and weight changes among men and women in the Health and Retirement Study | United States | 1994–2002 | 3725 | 1759 | 994 | Multiple Industries | |

| Yang et al. (2008) | Emergence of socioeconomic inequalities in smoking and overweight and obesity in early adulthood: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | United States | 1995–1996, 2001–2002 | 9542 | 4580 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Cho and Lee (2012) | The relationship between cardiovascular disease risk factors and gender | South Korea | 2005 | 4556 | 2596 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Duffy et al. (2012) | Predictors of Obesity in Michigan Operating Engineers | United States | 2008 | 498 | 37 | 37 | Specialty Trade Contractors | |

| Eshak et al. (2013) | Soft drink, 100% fruit juice, and vegetable juice intakes and risk of diabetes mellitus | Japan | 1990–2000 | 27585 | 15448 | 6565 | Multiple Industries | |

| Miura and Turrell (2014) | Reported consumption of takeaway food and its contribution to socioeconomic inequalities in body mass index | Australia | 2009 | 903 | 480 | 40 | Multiple Industries | |

| Lewin et al. (2014) | Residential neighborhood, geographic work environment, and work economic sector: associations with body fat measured by electrical impedance in the RECORD study | France | 2007–2008 | 4331 | NR | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Hwang and Lee (2014) | Effect of psychosocial factors on metabolic syndrome in male and female blue-collar workers | South Korea | 2010 | 234 | 80 | 80 | Chemical Manufacturing; Computer and Electronic Product Manufacturing; Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing; Transportation Equipment Manufacturing; | |

| Cancer | van Loon, Goldbohm, and van den Brandt (1994) | Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence: a prospective cohort study | Netherlands | 1986–1989 | 1716 | 1716 | 457 | Multiple Industries |

| van Loon, van den Brandt, and Golbohm (1995) | Socioeconomic status and colon cancer incidence: a prospective cohort study | Netherlands | 1986–1989 | 3658 | 1871 | 494 | Multiple Industries | |

| Cocco, Dosemeci, and Heineman (1998) | Occupational risk factors for cancer of the central nervous system: a case-control study on death certificates from 24 U.S. States | United States | 1984–1992 | 142,080 | 64,900 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Pollán & Gustavsson (1999) | High-risk occupations for breast cancer in the Swedish female working population | Sweden | 1971–1989 | 1,101,669 | 1,101,669 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Richardi et al. (2004) | Occupational risk factors for lung cancer in men and women: a population-based case-control study in Italy | Italy | 1990–2002 | 2724 | 476 | 476 | Multiple Industries | |

| Thompson et al. (2005) | Occupational exposure to metalworking fluids and risk of breast cancer among female autoworkers | United States | 1941–1994 | 4680 | 4680 | 4680 | Transportation Equipment Manufacturing | |

| Hrubá et al. (2009) | Socioeconomic indicators and risk of lung cancer in Central and Eastern Europe | Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Russia, and the United Kingdom | 1998–2001 | 5979 | 1469 | 617 | Multiple Industries | |

| Colt et al. (2011) | Occupation and bladder cancer in a population-based case-control study in Northern New England | United States | 2001–2004 | 2560 | 634 | 47 | Multiple Industries | |

| Betenia, Costello, and Eisen (2012) | Risk of cervical cancer among female autoworkers exposed to metalworking fluids | United States | 1985–2004 | 4374 | 4374 | 4374 | Transportation Equipment Manufacturing | |

| Oddone et al. (2013) | Female breast cancer in Lombardy, Italy (2002 - 2009): a case-control study on occupational risks | Italy | 2002–2009 | 78349 | 78349 | 36517 | Multiple Industries | |

| Pudrovska et al. (2013) | Higher-status occupations and breast cancer: a life-course stress approach | United States | 1951–2011 | 3682 | 3682 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Oddone et al. (2014) | Female breast cancer and electrical manufacturing: results of a nested case-control study | Italy | 2002–2009 | 216 | 216 | 145 | Computer and Electronic Product Manufacturing | |

| Cardiovascular disease | Zhao et al. (1991) | A dose response relation for noise induced hypertension | China | 1985 | 1101 | 1101 | 1101 | Textile Product Mills |

| Hall, Johnson, and Tsou (1993) | Women, occupation, and risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality | Sweden | 1977, 1979, 1980, 1981 | 5921 | 5921 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Hammar, Alfredsson, and Theorell (1994) | Job characteristics and the incidence of myocardial infarction | Sweden | 1970, 1985, 1976–1981, 1976–1984. | 35396 | 4667 | 2283 | Multiple Industries | |

| Melamed et al. (1995) | Objective and subjective work monotony: effects on job satisfaction, psychological distress, and absenteeism in blue-collar workers | Israel | 1985–1987 | 1278 | 393 | 393 | Manufacturing | |

| Jousilahti et al. (1996) | Symptoms of chronic bronchitis and the risk of coronary disease | Finland | 1972–1985, 1977–1990 | 19444 | 10102 | 766 | Multiple Industries | |

| Melamed et al. (1997) | Industrial noise exposure, noise annoyance e, and serum lipid levels in blue-collar workers--the CORDIS study | Israel | NR | 2079 | 624 | 624 | Manufacturing | |

| Wamala et al. (1997) | Lipid profile and socioeconomic status in health middle aged women in Sweden | Sweden | 1991–1994 | 300 | 300 | 64 | Multiple Industries | |

| Östlin et al. (1998) | Myocardial infarction in male and female dominated occupations | Sweden | 1969–1970, 1970–1990, 1971–1992, 1976–1984 | 140520 | 36708 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Baigi, Marklund, and Fridlund (2001) | The association between socio-economic status and chest pain focusing on self-rated health in a primary health care area of Sweden | Sweden | NR | 1145 | 492 | 404 | Multiple Industries | |

| Tsutsumi et al. (2001) | Association between job strain and prevalence of hypertension: a cross sectional analysis in a Japanese working population with a wide range of occupations: the Jichi Medical School cohort study | Japan | 1992–1994 | 6587 | 3400 | 1931 | Multiple Industries | |

| Wamala, Lynch, and Kaplan (2001) | Women's exposure to early and later life socioeconomic disadvantage and coronary heart disease risk: the Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study | Sweden | 1991–1994 | 585 | 177 | 177 | Multiple Industries | |

| Gallo et al. (2003) | Occupation and subclinical carotid artery disease in women: are clerical workers at greater risk? | United States | 1983–1985 | 362 | 362 | 27 | Multiple Industries | |

| Honjo et al. (2010) | Socioeconomic indicators and cardiovascular disease among Japanese community residents: The Jichi Medical School Cohort Study | Japan | 1992–2005 | 10640 | 6511 | 2084 | Multiple Industries | |

| Clougherty et al. (2011) | Gender and sex differences in job status and hypertension | United States | 1996–2002 | 14618 | 2016 | 793 | Primary Metal Manufacturing; Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing | |

| Tsutsumi, Kayaba, and Ishikawa (2011) | Impact of occupational stress on stroke across occupational classes and genders | Japan | 1992–2005 | 6553 | 3363 | 1867 | Multiple Industries | |

| Cho and Lee (2012) | The relationship between cardiovascular disease risk factors and gender | South Korea | 2005 | 4556 | 2596 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Stokholm et al. (2013) | Occupational noise exposure and the risk of hypertension | Denmark | 2001–2007 | 145190 | 36788 | 15728 | Multiple Industries | |

| Won et al. (2013) | Actual cardiovascular disease risk and related factors: a cross-sectional study of Korean blue-collar workers employed by small businesses | South Korea | 2010 | 238 | 82 | 82 | NR | |

| Fujishiro et al. (2015) | Occupational characteristics and the progression of carotid artery intima-media thickness and plaque over 9 years: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | United States | 2000–2011 | 3109 | 1610 | 166 | Multiple Industries | |

| Disability & absenteeism | Arber (1991) | Class, paid employment and family roles: making sense of structural disadvantage, gender and health status | United Kingdom | 1985–1986 | 26060 | 13283 | NR | Multiple Industries |

| Guendelman and Silberg (1993) | The health consequences of maquiladora work: women on the US-Mexican border | Mexico | 1990 | 480 | 480 | 241 | Computer and Electronic Products Manufacturing; Apparel Manufacturing; Accommodation and Food Services | |

| Vahtera et al. (1999) | Workplace as an origin of health inequalities | Finland | 1991–1993 | 2793 | 1875 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Korda et al. (2002) | The Health of the Australian workforce: 1998-2001 | Australia | 1998–2001 | 9167 | 4107 | 595 | Multiple Industries | |

| Aittomäki, Lahelma, and Roos (2003) | Work conditions and socioeconomic inequalities in work ability | Finland | 2000 | 1827 | 1398 | 161 | Multiple Industries | |

| Väänänen et al. (2004) | Role clarity, fairness, and organizational climate as predictors of sickness absence: a prospective study in the private sector | Finland | 1995–1998 | 3850 | 937 | 385 | Forestry and Logging | |

| Strong & Zimmerman (2005) | Occupational injury and absence from work among African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White workers in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth | United States | 1988–2000 | 35710 | 16839 | 1890 | Multiple Industries | |

| Christensen et al. (2008) | Explaining the social gradient in long-term sickness absence: a prospective study of Danish employees | Denmark | 2000–2002 | 5221 | 2562 | 671 | Multiple Industries | |

| Niedhammer et al. (2008) | The contribution of occupational factors to social inequalities in health: findings from the national French SUMER survey | France | 2003 | 24468 | 10245 | 1409 | Multiple Industries | |

| Väänänen et al. (2008) | Work-family characteristics as determinants of sickness absence: a large-scale cohort study of three occupational grades | Finland | 2000–2002 | 18366 | 13971 | 1802 | Multiple Industries | |

| von Bonsdorff et al. (2011) | Work ability in midlife as a predictor of mortality and disability in later life: a 28-year prospective follow-up study | Finland | 1981–2009 | 5971 | 3261 | 1692 | Multiple Industries | |

| Gupta et al. (2014) | Face validity of the single work ability item: comparison with objectively measured heart rate reserve over several days | Denmark | NR | 127 | 53 | 53 | Multiple Industries | |

| Heo et al. (2015) | Job stress as a risk factor for absences among manual workers: a 12-month follow-up study | South Korea | 2009–2010 | 2349 | 542 | 542 | Manufacturing | |

| Health behaviors | Burton and Turrell (2000) | Occupation, hours worked, and leisure-time physical activity | Australia | 1995 | 24454 | 11029 | 1972 | Multiple Industries |

| Wu and Porell (2000) | Job characteristics and leisure physical activity | United States | 1992 | 6443 | 2881 | 871 | Multiple Industries | |

| Gang et al. (2002) | Physical activity during leisure and commuting in Tianjin, China | China | 1996 | 3976 | 1974 | 809 | Multiple Industries | |

| Takao et al. (2003) | Occupational class and physical activity among Japanese employees | Japan | 1996–1998 | 20,654 | 3,017 | 1585 | Computer and Electronic Products Manufacturing; Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing; Primary Metal Manufacturing; Transportation Equipment Manufacturing | |

| McCormack, Giles-Corti, and Milligan (2006) | Demographic and individual correlates of achieving 10,000 steps/day: use of pedometers in a population-based study | Australia | NR | 428 | 223 | 19 | Multiple Industries | |

| Ericson et al. (2007) | Dietary intake of heterocyclic amines in relation to socioeconomic, lifestyle, and other dietary factors: estimates in a Swedish population | Sweden | 1991–1994 | 490 | 490 | 43 | Multiple Industries | |

| Kuiack, Irving, and Faulkner (2007) | Occupation, hours worked, caregiving, and leisure time physical activity | Canada | 2000 | 490 | 490 | 43 | Multiple Industries | |

| Harley et al. (2010) | Multiple health behavior changes in a cancer prevention intervention for construction workers, 2001 - 2003 | United States | 2002–2003 | 582 | 17 | 17 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Mäkinen et al. (2010) | Occupational class differences in leisure-time physical inactivity - contribution of past and current physical workload and other working conditions | Finland | 2000 | 3355 | 1788 | 273 | Multiple Industries | |

| Cleland et al. (2011) | Correlates of pedometer-measured and self-reported physical activity among young Australian adults | Australia | 2004–2006 | 2017 | 923 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Cho and Lee (2012) | The relationship between cardiovascular disease risk factors and gender | South Korea | 2005 | 4556 | 2596 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Miura and Turrell (2014) | Reported consumption of takeaway food and its contribution to socioeconomic inequalities in body mass index | Australia | 2009 | 903 | 480 | 40 | Multiple Industries | |

| Oliveira, Maia, and Lopes (2014) | Determinants of inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption amongst Portuguese adults | Portugal | 1999–2003 | 2362 | 1455 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Uijtdewilligen et al. (2014) | Biological, socio-demographic, work and lifestyle determinants of sitting in young adult women: a prospective cohort study | Australia | 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009 | 11676 | 11676 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Hwang et al. (2015) | Predictors of health-promoting behavior associated with cardiovascular diseases among Korean blue-collar workers | South Korea | NR | 234 | 80 | 80 | NR | |

| Uijtdewilligen et al. (2015) | Determinants of physical activity in a cohort of young adult women. Who is at risk of inactive behaviour? | Australia | 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009 | 11695 | 11695 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Mental health | Loscocco & Spitze (1990) | Working conditions, social support, and the well-being of female and male factory workers | United States | 1982 | 2222 | 649 | 649 | Multiple Industries |

| Parkinson et al. (1990) | Health effects of long-term solvent exposure among women in blue-collar occupations | United States | NR | 567 | 567 | 567 | Computer and Electronic Product Manufacturing | |

| Bromet et al. (1992) | Effects of occupational stress on the physical and psychological health of women in a microelectronics plant | United States | NR | 552 | 552 | 552 | Computer and Electronic Product Manufacturing | |

| Guendelman and Silberg (1993) | The health consequences of maquiladora work: women on the US-Mexican border | Mexico | 1990 | 480 | 480 | 241 | Computer and Electronic Products Manufacturing; Apparel Manufacturing; Accommodation and Food Services | |

| Melamed et al. (1995) | Objective and subjective work monotony: effects on job satisfaction, psychological distress, and absenteeism in blue-collar workers | Israel | 1985–1987 | 1278 | 393 | 393 | Manufacturing | |

| Kivimäki and Kalimo (1996) | Self-esteem and the occupational stress process: testing two alternative models in a sample of blue-collar workers | Finland | NR | 5450 | 927 | 927 | NR | |

| Goldenhar et al. (1998) | Stressors and adverse outcomes for female construction workers | United States | NR | 211 | 211 | 211 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Rydstedt, Johansson, and Evans (1998) | A longitudinal study of workload, health and well-being among male and female urban drivers | Sweden | 1991–1992 | 56 | 32 | 32 | Transit and Ground Passenger Transportation | |

| Soares, Grossi, and Sundin (2007) | Burnout among women: associations with demographic/socioeconomic, work, life-style and health factors | Sweden | NR | 6000 | 6000 | 745 | Multiple Industries | |

| Andrés, Collings, and Qin (2009) | Sex-specific impact of socio-economic factors on suicide risk: a population-based case-control study in Denmark | Denmark | 1981–1997 | 328608 | 109410 | 19922 | Multiple Industries | |

| Cohidon et al. (2009) | Mental health of workers in Toulouse 2 years after the industrial AZF disaster: first results of a longitudinal follow-up of 3,000 people | France | 2003–2008 | 2847 | 1514 | 53 | Multiple Industries | |

| Asztalos et al. (2009) | Specific associations between types of physical activity and components of mental health | Belgium | 2002–2004 | 1919 | 901 | 140 | Multiple Industries | |

| Brunette, Smith, and Punnett (2011) | Perceptions of working and living conditions among industrial male and female workers in Perú | Perú | 2002 | 1066 | 305 | 305 | Multiple Industries | |

| Moon and Park (2011) | Risk factors for suicidal ideation in Korean middle-aged adults: the role of socio-demographic status | South Korea | 2005 | 7301 | 4087 | 991 | Multiple Industries | |

| Ahlgren, Olsson, and Brulin (2012) | Gender analysis of musculoskeletal disorders and emotional exhaustion: interactive effects from physical and psychosocial work exposures and engagement in domestic work | Sweden | 2008 | 1373 | 515 | 253 | Food Manufacturing; Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | |

| Minh (2014) | Work-related depression and associated factors in a shoe manufacturing factory in Haiphong City, Vietnam | Vietnam | 2012 | 420 | 327 | 227 | Leather and Allied Product Manufacturing | |

| Yoon et al. (2014) | Occupational noise annoyance linked to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation: a result from nationwide survey of Korea | South Korea | 2007–2009 | 10020 | 4610 | 1934 | Multiple Industries | |

| Mortality | Hall, Johnson, and Tsou (1993) | Women, occupation, and risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality | Sweden | 1977, 1979, 1980, 1981 | 5921 | 5921 | NR | Multiple Industries |

| Pekkanen et al. (1995) | Social class, health behaviour, and mortality among men and women in Eastern Finland | Finland | 1970, 1972, 1975, 1977–1987 | 18661 | 9694 | 6376 | Multiple Industries | |

| Chenet et al. (1998) | Deaths from alcohol and violence in Moscow: socio-economic determinants | Russia | 1994–1995 | 86121 | 22619 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Arena et al. (1999) | Issues and findings in the evaluation of occupational risk among women high nickel alloys workers | United States | 1948–1988 | 2877 | 2877 | 2877 | Primary Metal Manufacturing | |

| Kareholt (2001) | The relationship between heart problems and mortality in different social classes | Sweden | 1968, 1974, 1981, 1991, 1992, 1968–1996 | 4585 | 2285 | 1170 | Multiple Industries | |

| Baigi et al. (2002) | Cardiovascular mortality focusing on socio-economic influence: the low-risk population f Halland compared to the population of Sweden as a whole | Sweden | 1980–1990 | 3247211 | 1592467 | 1250828 | Multiple Industries | |

| Prescott et al. (2003) | Social position and mortality from respiratory diseases in males and females | Denmark | 1976, 1978, 1981–1983, 1992–1993, 1964–1992 | 29392 | 13992 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Akerstedt, Kecklund, and Johansson (2004) | Shift work and mortality | Sweden | 1979–2000 | 22411 | 8401 | 4163 | Multiple Industries | |

| Mamo et al. (2005) | Factors other than risks in the workplace as determinants of socioeconomic differences in health in Italy | Italy | 1981–2001 | 377828 | 136212 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Bentley et al. (2007) | Area disadvantage, individual socio-economic position, and premature cancer mortality in Australia 1998 to 2000: a multilevel analysis | Australia | 1998–2000 | 5998961 | 2602424 | 382266 | Cross-Sectional | |

| Hein et al. (2007) | Follow-up study of chrysotile textile workers: cohort mortality and exposure-response | United States | 1916–2001 | 3072 | 1265 | 1256 | Textile Product Mills | |

| Lipton, Cunradi, and Chen (2008) | Smoking and all-cause mortality among a cohort of urban transit operators | United States | 1983–2000 | 1785 | 161 | 161 | Transit and Ground Passenger Transportation | |

| Brockmann, Müller, and Helmert (2009) | Time to retire - time to die? A prospective cohort study of the effects of early retirement on long-term survival | Germany | 1990–2004 | 129675 | 41276 | 26803 | Multiple Industries | |

| von Bonsdorff et al. (2011) | Work ability in midlife as a predictor of mortality and disability in later life: a 28-year prospective follow-up study | Finland | 1981–2009 | 5971 | 3261 | 1692 | Multiple Industries | |

| Dasgupta et al. (2012) | Multilevel determinants of breast cancer survival: association with geographic remoteness and area-level socioeconomic disadvantage | Australia | 1997–2006 | 18568 | 18568 | 715 | Multiple Industries | |

| von Bonsdorff et al. (2012) | Job strain among blue-collar and white-collar employees as a determinant of total mortality: a 28-year population-based follow-up | Finland | 1981–2009 | 5731 | 3261 | 1688 | Multiple Industries | |

| Hirokawa et al. (2013) | Mortality risks in relation to occupational category and position among the Japanese working population: the Jichi Medical School (JMS) cohort study | Japan | 1992–2005 | 6929 | 3596 | 1524 | Multiple Industries | |

| Mattisson, Horstmann, and Bogren (2014) | Relationship of SOC with sociodemographic variables, mental disorders, and mortality | Sweden | 1947, 1957, 1972, 1997–2011 | 1164 | 625 | 325 | Multiple Industries | |

| Costello et al. (2014) | Social disparities in heart disease risk and survivor bias among autoworkers: an examination based on survival models and g-estimation | United States | 1941–1995 | 39412 | 4797 | 4797 | Transportation Equipment Manufacturing | |

| Zhang et al. (2015) | Occupation and risk of sudden death in a United States community: a case-control analysis | United States | 2006–2013 | 1268 | 332 | 62 | Multiple Industries | |

| Musculoskeletal | Vingard et al. (1991) | Occupation and osteoarthrosis of the hip and knee: a register-based cohort study | Sweden | 1960, 1970, 1980, 1981–1983 | 250217 | 42549 | 42549 | Multiple Industries |

| Westgaard and Jansen (1992) | Individual and work related factors associated with symptoms of musculoskeletal complains. II Different risk factors among sewing machine operators | Norway | NR | 245 | 245 | 210 | Textile Product Mills | |

| Iverson and Erwin (1997) | Predicting occupational injury: the role of affectivity | Australia | NR | 362 | 65 | 65 | Manufacturing | |

| Fredriksson et al. (1999) | Risk factors for neck and upper limb disorders: results from 24 years of follow-up | Sweden | 1969–1993 | 484 | 252 | 37 | Multiple Industries | |

| Kaergaard and Andersen (2000) | Musculoskeletal disorders of the neck and shoulders in female sewing machine operators: prevalence, incidence and prognosis | Denmark | 1994–1997 | 243 | 243 | 243 | Textile Product Mills | |

| Murata, Kawakami, and Amari (2000) | Does job stress affect injury due to labor accident in Japanese male and female blue-collar workers? | Japan | 1989–1999 | 168 | 76 | 63 | Chemical Manufacturing | |

| Björkstén et al. (2001) | Reported neck and shoulder problems in female industrial workers: the importance of factors at work and at home | Sweden | NR | 173 | 173 | 173 | Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing; Food Manufacturing | |

| Khatun, Ahlgren, and Hammarström (2004) | The influence of factors identified in adolescence and early adulthood on social class inequities of musculoskeletal disorders at age 30: a prospective population-based cohort study | Sweden | 1981–1995 | 1044 | 497 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Kaila-Kangas et al. (2006) | How consistently distributed are the socioeconomic differences in severe back morbidity by age and gender? A population based study of hospitalisation among Finnish employees | Finland | 1995–1996 | 1517897 | 773936 | 193088 | Multiple Industries | |

| Nakata et al. (2006) | The prevalence and correlates of occupational injuries in small-scale manufacturing enterprises | Japan | 2002 | 1298 | 385 | 138 | Manufacturing | |

| Pollack et al. (2007) | Use of employer administrative databases to identify systematic causes of injury in aluminum manufacturing | United States | 2002–2004 | 9101 | 835 | 835 | Primary Metal Manufacturing | |

| Wang et al. (2007) | Work-organisational and personal factors associated with upper body musculoskeletal disorders among sewing machine operators | United States | 2003–2005 | 520 | 335 | 335 | Textile Product Mills | |

| Niedhammer et al. (2008) | The contribution of occupational factors to social inequalities in health: findings from the national French SUMER survey | France | 2003 | 24468 | 10245 | 1409 | Multiple Industries | |

| Taiwo et al. (2008) | Sex differences in injury patterns among workers in heavy manufacturing | United States | 1996–2005 | 9527 | 692 | 692 | Primary Metal Manufacturing | |

| Roquelaure et al. (2008) | Work increases the incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in the general population | France | 2002–2004 | 1168 | 819 | 194 | Multiple Industries | |

| Kim et al. (2009) | Depressive symptoms and self-reported occupational injury in small and medium-sized companies | South Korea | 2006–2007 | 1350 | 501 | 404 | Manufacturing | |

| Mattioli et al. (2009) | Risk factors for operated carpal tunnel syndrome: a multicenter population-based case-control study | Italy | 1997–1998, 2001 | 477 | 401 | 172 | Multiple Industries | |

| Roquelaure et al. (2009) | Attributable risk of carpal tunnel syndrome in the general population: implications for intervention programs in the workplace | France | 2002–2004 | 388078 | 194276 | 24090 | Multiple Industries | |

| Nag, Vyas, and Nag (2010) | Gender differences, work stressors, and musculoskeletal disorders in weaving industries | India | 2007 | 516 | 263 | 263 | Textile Product Mills | |

| Brunette, Smith, and Punnett (2011) | Perceptions of working and living conditions among industrial male and female workers in Perú | Perú | 2002 | 1066 | 305 | 305 | Multiple Industries | |

| Motamedzade and Moghimbeigi (2011) | Musculoskeletal disorders among female carpet weavers in Iran | Iran | NR | 626 | 626 | 626 | Textile Product Mills | |

| Ahlgren, Olsson, and Brulin (2012) | Gender analysis of musculoskeletal disorders and emotional exhaustion: interactive effects from physical and psychosocial work exposures and engagement in domestic work | Sweden | 2008 | 1373 | 515 | 253 | Food Manufacturing; Professional, Scientific and Technical Services | |

| Andersen et al. (2012) | Cumulative years in occupation and the risk of knee osteoarthritis in men and women: a register-based follow-up study | Denmark | 1981–2006 | 2117298 | 1100979 | 38485 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Lombardo et al. (2012) | Musculoskeletal symptoms among female garment factory workers in Sri Lanka | Sri Lanka | NR | 1058 | 1058 | 1000 | Apparel Manufacturing | |

| Kubo et al. (2013) | Associations between employee and manager gender: impacts on gender-specific risk of acute occupational injury in metal manufacturing | United States | 2002–2007 | 2645 | 2322 | 2322 | Primary Metal Manufacturing; Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing | |

| Lipscomb, Schoenfisch, and Cameron (2013) | Work-related injuries involving a hand or fingers among union carpenters in Washington state, 1989 - 2008 | United States | 1989–2008 | 24,830 | 646 | 646 | Specialty Trade Contractors | |

| Hanklang et al. (2014) | Musculoskeletal disorders among Thai women in construction-related work | Thailand | 2011 | 272 | 272 | 272 | Specialty Trade Contractors | |

| Tessier-Sherman (2014) | Occupational injury risk by sex in a manufacturing cohort | United States | 2001–2010 | 23956 | 5063 | 5063 | Primary Metal Manufacturing; Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing | |

| Cantley et al. (2015) | Expert ratings of job demand and job control as predictors of injury and musculoskeletal disorder risk in a manufacturing cohort | United States | 2004–2005 | 9260 | 946 | 946 | Primary Metal Manufacturing; Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing | |

| Hallman et al. (2015) | Association between objectively measured sitting time and neck-shoulder pain among blue-collar workers | Denmark | 2011–2012 | 202 | 84 | 84 | Multiple Industries | |

| Other | Parkinson et al. (1990) | Health effects of long-term solvent exposure among women in blue-collar occupations | United States | NR | 567 | 567 | 567 | Computer and Electronic Product Manufacturing |

| Bromet et al. (1992) | Effects of occupational stress on the physical and psychological health of women in a microelectronics plant | United States | NR | 552 | 552 | 552 | Computer and Electronic Product Manufacturing | |

| Grimmer (1993) | Relationship between occupation and episodes of headache that match cervical origin pain patterns | Australia | NR | 417 | 202 | 42 | Multiple Industries | |

| Tsai et al. (1997) | Neurobehavioral effects of occupational exposure to low-level organic solvents among Taiwanese workers in paint factories | Taiwan | 1992–1993 | 298 | 85 | 32 | Chemical Manufacturing | |

| Goldenhar, Swanson, & Hurrell (1998) | Stressors and adverse outcomes for female construction workers | United States | NR | 211 | 211 | 211 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Nguyen et al. (1998) | Noise levels and hearing ability of female workers in a textile factory in Vietnam | Vietnam | NR | 69 | 69 | 69 | Textile Mills | |

| Rydstedt, Johansson, and Evans (1998) | A longitudinal study of workload, health and well-being among male and female urban drivers | Sweden | 1991–1992 | 56 | 32 | 32 | Transit and Ground Passenger Transportation | |

| Juutilainen et al. (2000) | Nocturnal 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate excretion in female workers exposed to magnetic fields | Finland | NR | 60 | 60 | 39 | Apparel Manufacturing | |

| Shirom, Melamed, and Nir-Dotan (2000) | The relationships among objective and subjective environmental stress levels and serum uric acid: the moderating effect of perceived control | Israel | 1985–1987 | 3680 | 1176 | 1176 | Manufacturing | |

| Korda et al. (2002) | The Health of the Australian workforce: 1998-2001 | Australia | 1998–2001 | 9167 | 4107 | 595 | Multiple Industries | |

| Kovacevic and Belojevic (2006) | Tooth abrasion in workers exposed to noise in the Montenegrin Textile Industry | Serbia | NR | 225 | 225 | 111 | Textile Mills | |

| Potula and Kaye (2006) | The impact of menopause and lifestyle factors on blood and bone lead levels among female former smelter workers: the Bunker Hill Study | United States | 1994, 2000 | 73 | 73 | NR | Primary Metal Manufacturing | |

| Cobankara et al. (2011) | The prevalence of fibromyalgia among textile workers in the city of Denizli in Turkey | Turkey | 2005 | 655 | 523 | 523 | Textile Mills | |

| Choi et al. (2013) | Factors associated with sleep quality among operating engineers | United States | 2008 | 498 | 37 | 37 | Specialty Trade Contractors | |

| Lin et al. (2015) | Risk for work-related fatigue among the employees on semiconductor manufacturing lines | Taiwan | 2007 | 1545 | 428 | 428 | Computer and Electronic Product Manufacturing | |

| Reproductive & sexual health | Eskenazi, Guendelman, and Elkin (1993) | A preliminary study of reproductive outcomes of female maquiladora workers in Tijuana, Mexico | Mexico | 1990 | 360 | 360 | 241 | Computer and Electronic Products Manufacturing; Apparel Manufacturing; Accommodation and Food Services |

| Luoto, Kaprio, and Uutela (1994) | Age at natural menopause and sociodemographic status in Finland | Finland | 1989 | 1505 | 1505 | 511 | Multiple Industries | |

| Evans et al. (2003) | Predictors of seropositivity to herpes simplex virus type 2 in women | United Kingdom | 1992 | 520 | 520 | 88 | Multiple Industries | |

| Gissler et al. (2009) | Trends in socioeconomic differences in Finnish perinatal health 1991 - 2006 | Finland | 1991–2006 | 931285 | 931285 | 154359 | Multiple Industries | |

| Jakobsson and Mikoczy (2009) | Reproductive outcome in a cohort of male and female rubber workers: a registry study | Sweden | 1973–2001 | NR | NR | NR | Plastics and Rubber Products Manufacturing; Food Manufacturing | |

| Lalive & Zweimüller (2009) | How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments | Austria | 1985, 1987, 1990, 1993, 1996 | 6180 | 6180 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Sakr et al. (2010) | Reproductive outcomes among male and female workers at an aluminum smelter | United States | 2006 | 419 | 76 | 38 | Primary Metal Manufacturing | |

| Sayem et al. (2010) | An assessment of risk behaviours for HIV/AIDS among young female garment workers in Bangladesh | Bangladesh | 2007 | 300 | 300 | 300 | Apparel Manufacturing | |

| Yingying, Smith, and Suiming (2011) | Changes and correlates in multiple sexual partnerships among Chinese adult women--population based surveys in 2000 and 2006 | China | 2000, 2006 | 4525 | 4525 | 922 | Multiple Industries | |

| del Bono, Weber, and Winter-Ebmer (2012) | Clash of career and family: fertility decisions after job displacement | Austria | 1990–1998 | 227199 | 227199 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Pant et al. (2013) | Knowledge of and attitude towards HIV/AIDS and condom use among construction workers in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal | Nepal | 2013 | 317 | 33 | 33 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Räisänen et al. (2014) | Influence of delivery characteristics and socioeconomic status on giving birth by caesarean section - a cross sectional study during 2000–2010 in Finland | Finland | 2000–2010 | 620463 | 620463 | 90032 | Multiple Industries | |

| von Ehrenstein et al. (2014) | Preterm birth and prenatal maternal occupation: the role of Hispanic ethnicity and nativity in a population-based sample in Los Angeles, California | United States | 2003 | 2543 | 2,543 | 186 | Multiple Industries | |

| Wang et al. (2015) | Sulfur dioxide exposure and other factors affecting age at natural menopause in the Jinchuan cohort | China | 2012 | 3167 | 3167 | 2657 | Primary Metal Manufacturing | |

| Respiratory | Kongerud and Soyseth (1991) | Methacholine responsiveness, respiratory symptoms, and pulmonary function in aluminum potroom workers | Norway | 1988 | 337 | 38 | 38 | Primary Metal Manufacturing |

| Love et al. (1991) | The characteristics of respiratory ill health of wool textile workers | United Kingdom | NR | 620 | 145 | 145 | Textile Mills | |

| Raza et al. (1999) | Ventilatory function and personal breathing zone dust concentrations in Lancashire textile weavers | United Kingdom | NR | 302 | NR | NR | Textile Mills | |

| Seldén et al. (2001) | Exposure to tremolite asbestos and respiratory health in Swedish dolomite workers | Sweden | 1996 | 130 | 16 | 16 | Mining (except oil and gas); Nonmetallic Mineral Product Manufacturing | |

| Takezaki et al. (2001) | Dietary factors and lung cancer risk in Japanese: with special reference to fish consumption and adenocarcinomas | Japan | 1988–1997 | 5198 | 1486 | 178 | Multiple Industries | |

| Bakirci et al. (2007) | Natural history and risk factors of early respiratory responses to exposure to cotton dust in newly exposed workers | Turkey | NR | 157 | 74 | 74 | Textile Mills | |

| Heikkilä et al. (2008) | Asthma incidence in wood-processing industries in Finland in a register based population study | Finland | 1986–1998 | 170963 | 25148 | 16937 | Wood Product Manufacturing; Forestry and Logging | |

| Thilsing et al. (2012) | Chronic rhinosinusitis and occupational risk factors among 20- to 75-year-old Danes--a GA2LEN-based study | Denmark | 2008 | 2531 | 1331 | 550 | Multiple Industries | |

| Storaas et al. (2015) | Incidence of rhinitis and asthma related to welding in Northern Europe | Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia | 1990–1994, 1999–2001 | 16191 | 8398 | 219 | Fabricated Metal Product Manufacturing | |

| Wang et al. (2015) | Synergistic impaired effect between smoking and manganese dust exposure on pulmonary ventilation function in Guangxi Manganese-Exposed Workers Healthy Cohort (GXMEWHC) | China | 2011–2012 | 1658 | 620 | 620 | Primary Metal Manufacturing | |

| Self-Rated health | Korda et al. (2002) | The Health of the Australian workforce: 1998-2001 | Australia | 1998–2001 | 9167 | 4107 | 595 | Multiple Industries |

| Niedhammer et al. (2008) | The contribution of occupational factors to social inequalities in health: findings from the national French SUMER survey | France | 2003 | 24468 | 10245 | 1409 | Multiple Industries | |

| Brunette, Smith, and Punnett (2011) | Perceptions of working and living conditions among industrial male and female workers in Perú | Perú | 2002 | 1066 | 305 | 305 | Multiple Industries | |

| Hammarström, Stenlund, and Janlert (2011) | Mechanisms for the social gradient in health: results form a 14-year follow-up of the Northern Swedish Cohort | Sweden | 1981–1995 | 1083 | 495 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Landefeld et al. (2014) | The association between a living wage and subjective social status and self-rated health: a quasi-experimental study in the Dominican Republic | Dominican Republic | 2011 | 204 | 134 | 134 | Apparel Manufacturing | |

| Smoking & Other Substance Use | Cunradi, Lipton, and Banerjee (2007) | Occupational correlates of smoking among urban transit operators: a prospective study | United States | 1983–1985; 1993–1995 | 654 | 54 | 54 | Transit and Ground Passenger Transportation |

| Radi, Ostry, and LaMontagne (2007) | Job stress and other working conditions: relationships with smoking behaviors in a representative sample of working Australians | Australia | NR | 1101 | 575 | 74 | Multiple Industries | |

| Yang et al. (2008) | Emergence of socioeconomic inequalities in smoking and overweight and obesity in early adulthood: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | United States | 1995–1996, 2001–2002 | 9542 | 4580 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Okechukwu, Nguyen, and Hickman (2010) | Partner smoking characteristics: associations with smoking and quitting among blue-collar apprentices | United States | NR | 1767 | 88 | 88 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Sayem et al. (2010) | An assessment of risk behaviours for HIV/AIDS among young female garment workers in Bangladesh | Bangladesh | 2007 | 300 | 300 | 300 | Apparel Manufacturing | |

| Biron, Bamberger, and Noyman (2011) | Work-related risk factors and employee substance use: insights from a sample of Israeli blue-collar workers | Israel | NR | 569 | NR | NR | Manufacturing | |

| Hammarström et al. (2011) | Mechanisms for the social gradient in health: results form a 14-year follow-up of the Northern Swedish Cohort | Sweden | 1981–1995 | 1083 | 495 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Chin et al. (2012) | Cigarette smoking in building trades workers: the impact of work environment | United States | 2004–2007 | 1817 | 88 | 88 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Chin et al. (2012) | Occupational factors and smoking cessation among unionized building trades workers | United States | 2004– 2007 | 763 | 44 | 44 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Chin et al. (2013) | Heavy and light/moderate smoking among building trades construction workers | United States | NR | 763 | 63 | 63 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Cho and Lee (2012) | The relationship between cardiovascular disease risk factors and gender | South Korea | 2005 | 4556 | 2596 | NR | Multiple Industries | |

| Fujishiro et al. (2012) | Occupational gradients in smoking behavior and exposure to workplace environmental tobacco smoke: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | United States | 2000–2002 | 6355 | 3249 | 373 | Multiple Industries | |

| Noonan and Duffy (2012) | Smokeless tobacco use among operating engineers | United States | 2008 | 498 | 37 | 37 | Specialty Trade Contractors | |

| Okechukwu et al. (2012) | Smoking among construction workers: the nonlinear influence of the economy, cigarette prices, and antismoking sentiment | United States | 1992–1993, 1995–1996, 1998–1999, 2001–2002, 2003, 2006–2007 | 52418 | 1479 | 1479 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Cunradi, Ames, and Xiao (2014) | Binge drinking, smoking and marijuana use: the role of women's labor force participation | United States | 2006–2007 | 956 | 956 | 104 | Construction of Buildings | |

| Maron et al. (2015) | Occupational inequalities in psychoactive substance use: a question of conceptualization | Germany | 2012 | 9084 | 5155 | 994 | Multiple Industries |

| Outcome Category | Study Design | Independent Variable(s)** | Specific Outcome | Referent Group | Summary of Study Findings | Brief Description of Study Population | Country Classification | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI & metabolism | Cross-Sectional | Age, sex, education, ethnic origin, repetitive work (short, medium, and long-cycle), work underload, subjective monotony | Serum glucose levels | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, short-cycle repetitive work was associated with higher serum glucose (p = 0.05) levels. | Cardiovascular Occupational Risk Factors Determination in Israel Study (CORDIS) | High-Income | (Melamed et al., 1995) |

| Cross-Sectional | Occupational class, marital status | Waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio | Blue-collar women vs. other women | Among blue-collar women, waist circumference (ß = -2.40, SE = 8.19) and waist to hip ratio (ß = -0.0294, SE = 0.0065) were lower as compared with white-collar women. | Employees from a single Japanese computer and printing manufacturing company | High-Income | (Nakamura et al., 2000) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Age, education, occupational class, marital status, smoking status, regular physical exercise, physical activity tertiles, total energy intake quartiles | Obesity | Blue-collar women vs. other womenC | The odds of obesity among blue-collar women were increased as compared with white-collar women (OR = 3.5, 95% CI 2.21– 5.55). | Adults living in Porto, Portugal recruited with random digit-dialing | High-Income | (Santos & Barros, 2003) | |

| Longitudinal | Education, log-income, occupational class | Type 2 Diabetes | Blue-collar women vs. other women | The hazard of type 2 diabetes among blue-collar women was increased as compared with white-collar women (HR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.53 –1.41). | Alameda County Study | High-Income | (Maty et al., 2005) | |

| Longitudinal | Parental occupation; childhood household deprivation (public assistance, no plumbing, no electricity, food scarcity); adult SEP index; education; occupational class; lifecourse SEP | Weight Change | Blue-collar women vs. other womenC | Blue-collar women demonstrated larger 13- year increases in BMI as compared with white-collar women (5.8 vs. 4.8 kg/m2, p 0.05). | Pitt County Study | High-Income | (Bennett et al., 2007) | |

| Longitudinal | Recent Retirement | Weight loss of 5% or greater; weight gain of 5% or greater | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, retirement was inversely associated with a weight loss of 5% or greater (OR = 0.88, 95% 0.57–1.37). Retirement was positively associated with a weight gain of 5% or greater (OR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.13–2.21). | Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | High-Income | (Forman-Hoffman et al., 2008) | |

| Longitudinal | Young adult socioeconomic position (education and occupational class); family socioeconomic position; family structure; family connectedness; smoker in home; easy access to cigarettes; high school; CES-D; number of friends who smoke; BMI during adolescence | Overweight, Obesity | Blue-collar women vs. other womenC | Odds of overweight (OR = 1.04, 0.49–2.21) or obesity (OR = 0.74, 0.29 –1.85) were not increased among blue-collar women as compared to women with further education. | National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | High-Income | (Yang et al., 2008) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Occupational class, education, poverty-income ratio | Obesity | Blue-collar women vs. other womenC | The odds of obesity among blue-collar women were increased as compared with white-collar women (OR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.43–3.05). | Third Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES III) | High-Income | (Cho and Lee, 2012) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Age, female, white, married, high-school or less, SF-36 pain, self-reported medical comorbidities, depression, smoking, alcohol problem, vegetable intake, fruit intake, fried food intake, physical activity | Obesity | Male vs. female blue-collar workersC | The odds of obesity among female operating engineers were decreased as compared with male operating engineers (OR = 0.283, 95% CI 0.083–0.827). | Convenience sample of operating engineers recruited during a three-day safety training course | High-Income | (Duffy et al., 2012) | |

| Longitudinal | Soft drinks intake, 100% fruit juice intake, vegetable juice intake, age, sports activity, education, occupational class, BMI, Menopausal status | Diabetes Mellitus | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, the odds of type 2 diabetes were increased among those who drank soda every day (OR = 2.57, 95% CI 1.25–5.29); those who drank soda 3-4 times per week (OR = 125, 95% CI 0.66–2.35); and those who drank soda two times or less per week (OR = 1.18, 95% CI 0.77–1.80) as compared with those who rarely drank soda. | Japan Public Health Center Study (JPHC) | High-Income | (Eshak et al., 2013) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Education, household income, occupational class | Healthy takeaway food; less healthy takeaway food | Blue-collar women vs. other women | Blue-collar women had increased BMI as compared with professionals and managers (ß = 2.83, SE = 0.99). | Adults randomly selected form the electoral roll of the Brisbane statistical subdivision. | High-Income | (Miura and Turrell, 2014) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Age, individual education, parental education, HDI of country of birth, residential education level, residential density of population, occupational class, home work distance | Fat Mass Index | Blue-collar women vs. other women | There was no significant association between work economic sector and fat mass index (FMI) for women in the manufacturing industry (ß = 0.31, 95% CI 0.04–1.73); construction (ß = 0.18, 95% CI - 2.44 to 2.81); or commercial repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (ß = 0.43, 95%CI - 0.60 to 1.46) as compared with women in transport and communications. | Residential Environment and Coronary Heart Disease Cohort Study (RECORD) | High-Income | (Lewin et al., 2014) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Overtime work (≥ 60 hours/week), social support, job stress, risk perception, physical exercise (≥ 30 min, ≥ 3 per week) | Metabolic Syndrome | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, low job stress (OR = 0.05, p = 0.04), low social support (OR = 1.51, p = 0.009), and risk perception (OR = 1.27, p = 0.023) were associated with metabolic syndrome. | Blue-collar workers at small companies recruited from occupational health centers or worksites during annual health checkups in South Korea. | High-Income | (Hwang and Lee, 2014) | |

| Cancer | Longitudinal | Highest level of education, highest level of education (household), EPG score: last profession, U&S score: last profession | Breast Cancer | Blue-collar women vs. other women | There was no difference in breast cancer risk in blue-collar women and lower white-collar women (RR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.69–1.49); the risk of breast cancer was increased among upper white-collar women as compared with blue-collar women (RR = 1.19, 95% CI 0.80 –1.76). | The Netherlands Cohort Study (NLCS) | High-Income | (Van Loon et al., 1994) |

| Longitudinal | Highest level of education, occupational class, social standing (U&S) score | Colon Cancer | Blue-collar women vs. other women | As compared with blue-collar women, the risk of colon cancer was increased among lower white-collar women (RR = 1.30, 95% CI 0.76–2.22) but decreased among upper white-collar women (RR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.30–1.29) | The Netherlands Cohort Study (NLCS) | High-Income | (Van Loon et al., 1995) | |

| Case-Control | Occupation | Cancer of the CNS | Blue-collar women vs. other women | Industries showing consistent increases in risk for cancer of the CNS by gender and race included textile mills, paper mills, printing and publishing industries, petroleum refining, motor vehicles manufacturing, telephone and electric utilities, department stores, health care services, elementary and secondary schools, and colleges and universities. | United States Vital Statistics Records | High-Income | (Cocco et al., 1999) | |

| Longitudinal | Occupation | Breast Cancer | Blue-collar women vs. other women | Excess risk for breast cancer was found for pharmacists, teachers of theoretical subjects, schoolmasters, systems analysts and programmers, telephone operators, telegraph and radio operators, metal platers and coaters, and hairdressers and beauticians. | All living Swedish women ages 25–64 who were employed at the time of the 1970 census and present in the country during the 1960 census. | High-Income | (Pollán and Gustavsson, 1999) | |

| Case-Control | Exposure to known and suspected lung carcinogens. | Lung Cancer | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Lung cancer risk was increased among female rubber workers exposed to suspected carcinogens versus those unexposed (OR = 2.2, 95% CI = 0.6–7.9); among female glass workers exposed to suspected carcinogens versus those unexposed (OR = 2.8, 95% CI 0.4–22); and among laundry and dry cleaners exposed to suspected carcinogens versus those unexposed (OR = 2.1, 95% CI = 0.8–5.6). | Incident lung cancer cases and population controls in Northern Italy | High-Income | (Richiardi et al., 2004) | |

| Case-Control | Metalworking fluid (MWF) | Breast Cancer | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | There was an increase in the odds of breast cancer associated with every mg/m3-year increase of cumulative exposure to soluble MWF over the ten-year study period (OR = 1.18, 95% CI 1.02–1.35). | Female hourly automobile production workers from three large manufacturing plants in Michigan | High-Income | (Thompson et al., 2005) | |

| Case-Control | Occupational class, education | Lung Cancer | Blue-collar women vs. other women | The odds of lung cancer among blue-collar women were decreased as compared with white-collar women (OR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.74–1.25). | Incident lung cancer cases and hospital-based controls in seven Eastern European countries. | High-Income and Upper-Middle-Income | (Hrubá et al., 2009) | |

| Case-Control | Occupation of first employment | Bladder Cancer | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among women, bladder cancer risk was significantly elevated and increased significantly with duration of employment in the electronic components and accessories industry (OR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.7) and the transportation equipment industry (OR = 8.7, 95% CI 2.0–37). | Incident bladder cancer cases and population controls in Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire. | High-Income | (Colt et al., 2011) | |

| Longitudinal | Metalworking fluid (MWF) | Cervical Cancer | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | There was no difference in cervical cancer risk among blue-collar women exposed or not exposed to straight MWF (RR = 1.0, 95% CI 0.46–2.19). Risk of cervical cancer among blue-collar women exposed to soluble MWF increased as compared with unexposed workers (RR = 1.55, 95% CI 0.66–3.61). Risk of cervical cancer among blue-collar women exposed to synthetic MWF increased as compared with unexposed women (RR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.50–2.60). | Female hourly automobile production workers from three large manufacturing plants in Michigan | High-Income | (Betenia et al., 2012) | |

| Case-Control | Duration of Employment | Breast Cancer | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | The odds of breast cancer among women with 20+ years of employment versus those with 0 to 4 years of employment were increased in the iron and steel industry (OR = 1.22, 95% CI 0.72–2.07); mechanical manufacturing (OR = 1.11, 95% CI 0.92–1.34); electrical manufacturing (OR = 1.37, 95% CI 1.10–1.71); the food industry (OR = 1.13, 95% CI 0.83–1.19); the textile industry (OR = 1.13, 95% CI 0.98–1.29); the garment industry (OR = 1.16, 95% CI 1.01–1.34); the wood industry (OR = 1.22, 95% CI 0.80–1.85); the rubber industry (OR = 2.71, 95% CI 1.25–5.87); the building industry (OR = 1.45, 95% CI 0.28–7.59); the transport industry (OR = 1.15, 95% CI 0.34–3.93); the chemical industry (OR = 1.52, 95% CI 0.96–2.42); the alcoholic beverages and wine production industry (OR = 1.46, 95% CI 0.26–8.10); the pharmaceutical industry (OR = 1.31, 95% CI 0.70–2.43); and the dry cleaning sector (OR = 2.29, 95% CI 0.97–5.41) but not for women in healthcare and veterinarian services, the plastic industry, the pottery industry, agriculture, the paper industry, the leather and shoe industry, or the press industry. | Incident cases of female breast cancer and population controls in Lombardy, Italy | High-Income | (Oddone et al., 2013) | |

| Longitudinal | Occupational class in 1993 and 1975; high job authority in 1975; adiposity in 1957; reproductive history in 1975 and 1993; job characteristics in 1975; health behaviors in 1993; work under pressure of time, responsibility outside control, high job autonomy; job satisfaction; high job authority; life-course estrogen cycle; family history of breast cancer | Breast Cancer | Blue-collar women vs. other women | The risk of breast cancer was increased among female crafts/operatives laborers as compared with housewives (HR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.51–1.48). | Wisconsin Longitudinal Survey (WLS) | High-Income | (Pudrovska et al., 2013) | |

| Case-Control | Exposure to lead and lead alloys, chlorinated solvents, lubricant oils, non-ionizing radiation, epoxy resins, and job title | Breast Cancer | Blue-collar women vs. other women | The odds of breast cancer were increased among blue-collar women exposed to chlorinated solvents as compared with unexposed women (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.04−2.62). There was a two-fold increase among blue-collar women exposed for at least 10 years as compared with unexposed women (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.21−3.66). | Incident cases of female breast cancer and controls selected from a single, large electrical manufacturing plant near Milan, Italy. | High-Income | (Oddone et al., 2014) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | Cross-Sectional | Sound pressure level, age, working years, salt (high), salt (normal), family history | Hypertension | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among female textile mill workers, sound pressure levels (SPL) were associated with the prevalence of hypertension (ß = 0.03, SE = 0.015). | Female workers in a textile mill in Beijing, China | Upper-Middle-Income | (Zhao et al., 1991) |

| Longitudinal | Occupational class, work control, work social support, psychological job demand, physical job demand | Cardiovascular morbidity | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, cardiovascular morbidity was more prevalent among those with low work social support (OR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.01–1.14) and high physical job demand (OR = 1.15, 95% CI 0.97–1.35). Cardiovascular disease was less prevalent among blue-collar women with high psychological job demand (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.60–0.97). There was no association between work control and cardiovascular morbidity (OR = 1.02, 95% CI 087–1.20). | Survey of Living Conditions | High-Income | (Hall et al., 1993) | |

| Case-Control | Job characteristics | Myocardial Infarction | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, increased risk of first MI was associated with monotony (RR = 1.4, 95% CI 0.3–6.9) few possibilities to learn new things (RR = 2.1, 95% CI = 0.9–4.9), long working hours (RR = 1.1, 95% CI 0.7–1.7), low influence on planning of work (RR = 2.0, 95% CI = 0.3–15.6), low influence on working hours (RR = 1.1, 95% CI 0.8–1.7), and noise (RR = 1.4, 95% CI 0.9–2.1). Decreased risk of MI was associated with hectic work (RR = 0.7, 95% CI 0.5–1.1) and low influence on work tempo (RR = 0.7, 95% CI 0.4–1.3) | Incident cases of myocardial infarction and population-based controls in four rural Swedish Counties and Stockholm County. | High-Income | (Hammar et al., 1994) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Age, sex, education, ethnic origin, repetitive work (short, medium, and long-cycle), work underload, subjective monotony | Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, short-cycle repetitive work was associated with higher mean systolic (p = 0.003) and diastolic (p = 0.01) blood pressure; and total cholesterol (p = 0.03). | Cardiovascular Occupational Risk Factors Determination in Israel Study (CORDIS) | High-Income | (Melamed et al., 1995) | |

| Longitudinal | Symptoms of chronic bronchitis | First coronary event | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, the risk of first coronary event was increased among those with Grade 1 symptoms (RR = 1.98, 95% CI 0.56–7.01) and those with Grade 2 symptoms (RR = 1.93, 95% CI 0.69–5.39) as compared with blue-collar women with no symptoms. | A random sample of the population of the eastern Finnish provinces of North Karelia and Kuopio. | High-Income | (Jousilahti et al., 1996) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Noise-exposure level, noise annoyance | Cholesterol, LDL, HDL, Cholesterol/HDL, triglycerides | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women with high noise-exposure and high noise-annoyance, the mean-adjusted cholesterol level was 207 mg/dl (SE = 9.4); LDL levels were 125 mg/dl (SE = 8.6); HDL levels were 57 mg/dl (SE = 3.1); the ratio of Cholesterol to HDL was 4.1 (SE = 0.3) and the mean-adjusted triglyceride level was 126 mg/dl (SE = 14.0). | Cardiovascular Occupational Risk Factors Determination in Israel Study (CORDIS) | High-Income | (Melamed et al., 1997) | |

| Case-Control | Education, occupational level, decision latitude at work | Cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, Cholesterol/HDL, LDL/HDL, ApoB, ApoA1 | Blue-collar women vs. other women | As compared with white-collar women, cholesterol levels (difference = 0.11, p = 0.42), triglyceride levels (difference = 0.07, p = 0.78), HDL levels (difference = 0.09, p = 0.23), the cholesterol to HDL ratio (difference = 0.36, p = 0.17), the LDL to HDL ratio (difference = 0.31, p = 0.18), and the Apolipoprotein B to apolipoprotein A1 ratio (difference = 0.06, p = 0.63) were higher among blue-collar women. | Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study (FemCorRisk) | High-Income | (Wamala et al., 1997) | |

| Case-Control | Occupational class, male- or female-dominated occupation | Myocardial Infarction | Blue-collar women vs. other women | Increased risk of MI was found among blue-collar women (RR = 1.41, 95%CI 1.15–1.73) in jobs where men predominate as compared with other women. | Population aged 30-74 residing in one of five Swedish counties including Stockholm. | High-Income | (Ostlin et al., 1998) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Age, occupational class | Pain or discomfort in the chest when excited; pain or discomfort in the chest after a substantial meal; Palpitation of the heart or irregular heartbeat | Blue-collar women vs. other women | As compared with blue-collar women, white-collar women experienced less pain or discomfort in the chest when excited (OR = 0.42, 95% CI 0.26–0.68). There was no difference in the odds of pain or discomfort in the chest after a substantial meal (OR = 1.05, 95% CI 0.45–2.44) or palpitations of the heart or irregular heartbeat (OR = 0.99, 95% CI 0.71–1.38). | A stratified sample of residents aged 18 to 74 in the four primary health care areas of Halland County, Sweden. | High-Income | (Baigi et al., 2001) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Job strain | Hypertension | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | There was no association between job strain and hypertension among blue-collar women (OR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.87–1.17). | The Jichi Medical School Cohort Study (JMS) | High-Income | (Tsutsumi et al., 2001) | |

| Case-Control | Short stature, early life socioeconomic disadvantage (large early life family size, singletons, born last, low education), adult life socioeconomic disadvantage (occupational class at labour force entry, blue-collar occupation at examination, economic hardship prior to CHD event). | Coronary heart disease | Blue-collar women vs. other women | The odds of CHD were increased among women whose occupation at labor force entry was blue-collar as compared with women whose occupation at labor force entry was white-collar (OR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.12–3.12). The odds of CHD among women whose occupation at examination was blue-collar as compared to women whose occupation at examination was white-collar (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 0.95–2.88). | Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study (FemCorRisk) | High-Income | (Wamala et al., 2001) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Age, behavioral risk factors, occupational class | Average carotid intima-media thickness | Blue-collar women vs. other women | Carotid intima-media thickness was reduced among blue-collar women as compared with female clerical workers (ß = -0.064, SE = 0.027). | Healthy Women Study (HWS) | High-Income | (Gallo et al., 2003) | |

| Longitudinal | Occupational class | Total stroke, intraparanchymal hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, coronary heart disease | Blue-collar women vs. other women | As compared with blue-collar women, white-collar women had lower risk of total stroke (HR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.58–1.51), intraparenchymal hemorrhage (HR = 0.34, 95% CI 0.09–1.21), ischemic stroke (HR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.36–1.47), and coronary heart disease (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.20–2.21). Risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage was increased among white-collar women compared with blue-collar women (HR = 2.68, 1.03–6.94). | The Jichi Medical School Cohort Study (JMS) | High-Income | (Honjo et al., 2010) | |

| Longitudinal | Occupational class | Hypertension | Blue-collar women vs. other women | Among women, there was an association between hourly (i.e. blue-collar) status and hypertension among those predicted to be hourly workers based on propensity scores (OR = 1.78, 95% CI 1.34–2.35). | The American Manufacturing Cohort Study (AMC) | High-Income | (Clougherty et al., 2011) | |

| Longitudinal | Job characteristics | Stroke | Exposure-outcome among blue-collar women | Among blue-collar women, there was no association between risk of incident stroke among women with active jobs (HR = 0.9, 95% CI 0.3–24), passive jobs (HR = 1.0, 95% CI 0.4–2.4), or high strain jobs (HR = 1.04, 95% CI 0.4–2.5) as compared to those with low-strain jobs. | The Jichi Medical School Cohort Study (JMS) | High-Income | (Tsutsumi et al., 2011) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Occupational class, education, poverty-income ratio | Hypertension, non-HDL Cholesterol | Blue-collar women vs. other women | The odds of hypertension among blue-collar women were increased (OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.04–1.61) and the odds of NHDLC were decreased (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.51–1.09) as compared with white-collar women. | Third Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES III) | High-Income | (Cho and Lee, 2012) | |

| Longitudinal | Cumulative noise exposure, duration of exposure, first year of exposure | Hypertension | Blue-collar women vs. other women | The risk of hypertension among female industrial workers is increased as compared with female financial workers (RR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.09–1.26). | Workers employed in one of 625 companies in the industrial trades and 100 companies in the financial services in Aarhaus County, Denmark. | High-Income | (Stokholm et al., 2013) | |

| Cross-Sectional | Age, gender, education, knowledge of CVD risk, CVD risk perception, waist-to-hip ratio, social support, ERI ratio (job stress), exposure to chemicals or noise, shift work, overtime work | Actual CVD Risk | Male vs. female blue-collar workersC | Actual cardiovascular disease risk among blue-collar women was decreased as compared with blue-collar men (ß = - 0.092, p = 0.709). | Blue-collar workers from companies with fewer than 300 employees recruited through an occupational health center in South Korea. | High-Income | (Won et al., 2013) | |

| Longitudinal | Occupational class | Annual and baseline differences in common carotid intima-media thickness (IMT), carotid plaque score, and prevalence of carotid plaque showing. | Blue-collar women vs. other women | Compared with professional women at baseline, the common carotid IMT was increased (0.005, 95% -0.026 to 0.035), the carotid plaque score was decreased (-0.04, 95% CI - 22.7 to 28.3) and the prevalence of carotid plaque showing was decreased (-12.6, 95% CI - 41.7 to 31.2) in blue-collar women. Compared with professionals, the annual change in common carotid IMT was smaller (-0.001, 95% CI - 0.003 to 0.002), the annual change in carotid plaque score was greater (0.03, 95% CI - 2.0 to 2.7) and the annual change in the prevalence of carotid plaque showing was greater (2.0, 95% CI - 2.9 to 7.1) in blue-collar women. | Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | High-Income | (Fujishiro et al., 2015) | |