Abstract

Background

CircRNAs are widespread in plants and play important roles in response to abiotic stresses. Low nitrogen (LN) promotes the growth of plant root system, allowing it to explore more nitrogen. However, whether circRNAs involved in the response to LN stress and the regulation of LN-promoted root growth in wheat remains unclear.

Methods

Two wheat varieties (LH9 and XN979) with contrasting root phenotypes to LN stress were used as materials to identify circRNAs under control and LN conditions by using high-throughput sequencing technology.

Results

Six differentially expressed circRNAs (DECs) involved in the common response to LN stress and 23 DECs involved in the regulation of LN-promoted root growth were successfully identified. GO analysis of the DEC-host genes involved in the regulation of LN-promoted root growth showed that GO terms related to biological regulation, responses to stimuli and signalling were significantly enriched. Moreover, seven DECs were predicted to have miRNA binding sites and may serve as miRNA sponges to capture miRNAs from their target genes.

Conclusions

LN stress altered the expression profiles of circRNAs in wheat. This is the first report of LN stress responsive circRNAs in plants. Our results provided new clues for investigating the functions of circRNAs in response to LN stress and in the regulation of LN-promoted wheat root growth.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40659-018-0194-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Triticum aestivum L., Root, Low nitrogen, CircRNAs

Background

Plant roots have high plasticity in response to varying different environmental conditions [1–5]. The nitrogen deficiency environment promotes the growth of plant root system, allowing it to reach deeper soil layers and explore more nitrogen. Therefore, the ability to develop a deep root system under nitrogen limiting conditions is of vital importance for nitrogen acquisition.

CircRNAs are a type of endogenous non-coding RNAs derived from mRNA precursor back-splicing [6]. The 5′ and 3′ ends in mature circRNAs have been jointed together, forming covalently closed loop structures [7]. The identification, biogenesis and functions of circRNAs have been widely reported in animals, such as human, mouse and Drosophila [8–11]. However, the roles of circRNAs in plants have not attracted enough attention [12]. With the development and wide application of high-throughput sequencing technology, circRNAs have been identified in Arabidopsis [13–16], soybean [17], rice [13, 18], tomato [19], barley [20], cotton [21], maize [22], wheat [23] and some other plant species in recent years [24, 25]. Ye et al. identified 12,037 and 6012 circRNAs in rice and Arabidopsis thaliana, respectively [13]. Lu et al. also reported 2354 circRNAs in Oryza sativa [18]. These reports indicate that circRNAs are widespread in plants and may play important roles in the regulation of plant growth and development. Zuo et al. identified 854 circRNAs and found that 163 of them were chilling responsive in tomato [19]. Zhao et al. identified 1041, 1478, 1311 and 499 circRNAs in diploid progenitors of Gossypium spp., G. arboreum and G. raimondii, their interspecies hybrid and allotetraploid G. hirsutum, respectively [21]. Wang et al. isolated 88 circRNAs and found that 62 circRNAs were differentially expressed under dehydration stress conditions compared with well-watered control in wheat [23]. Chen et al. [22] found that circRNAs mediated by transposons are associated with transcriptomic and phenotypic variation in maize. In rice, some circRNAs exhibit differential expression under Pi-sufficient and Pi-starvation conditions, suggesting that circRNAs may play a role in response to Pi starvation stress [13]. These studies indicate that circRNAs may also play important roles in response to abiotic stresses in plants. However, whether circRNAs participate in the response of plants to low nitrogen (LN) stress and the process of LN-promoted root growth remains to be elucidated.

To explore this question, circRNAs expression profiles of two elite Chinese wheat varieties with contrasting phenotypes to LN stress were obtained using high-throughput sequencing technology. Differentially expressed circRNAs (DECs) were identified and further validated using real-time PCR technology. Moreover, target miRNAs of DECs were predicted and discussed.

Methods

Plant materials

Xinong 979 (XN979) and Luohan 9 (LH9) are two elite Chinese wheat varieties with contrasting root phenotypes to LN stress. Therefore, XN979 and LH9 were selected as materials to explore potential circRNAs involved in the processes of LN stress response and LN-promoted root growth.

Plant growth conditions and evaluation of root phenotype

Hydroponic culture was used to investigate the root traits and collect root samples. Methods for seed sterilization, germination, and the growth conditions of wheat plants were conducted according to Ren et al. [26]. Plants were randomly placed and grown in a greenhouse with at least six replications each. Germinated XN979 and LH9 seeds with residual endosperm removed were transferred to CK (2.0 mM NO3−) and LN (0.1 mM NO3−) nutrient solutions. The nutrient solutions were refreshed every 2 days and its pH was adjusted to 6.0 with dilute HCl and KOH before refreshing. The maximum root length (MRL) and root dry weight (RDW) of XN979 and LH9 were evaluated at 15 days after transfer. The developmental stages of wheat plants were Zadoks growth scale 12 and 13 under LN and CK conditions, respectively [27]. The roots of XN979 and LH9 under CK and LN conditions were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at – 80 °C for RNA extraction.

Libraries construction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of total RNA were measured with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Ribosomal RNAs (rRNA) were depleted using the Epicentre Ribo-Zero Gold Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA libraries were constructed using the rRNA-depleted total RNAs as templates according to the protocol of the mRNA-Seq sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Then the libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform (Hangzhou Shangyi biotechnology company, Hangzhou, China). Three biological replicates were analyzed to minimize experimental errors and the number of false positives. The 12 samples were named as LH9_CK-1, -2, -3; LH9_LN-1, -2 -3; XN979_CK-1, -2, -3 and XN979_LN-1, -2, -3, respectively.

Identification of circRNAs

The clean reads were mapped to the reference genome (Triticum aestivum TGACv1.0) by the bowtie2 (bowtie2-2.2.2) alignment method. The reads of linear RNAs can be mapped to the reference genome properly, while the reads at the loop-forming ligation sites of circRNAs cannot be directly aligned to the wheat reference genome. The unmapped RNA-seq reads were used to further detect head-to-tail spliced (back-spliced) sequencing reads by find_circ software. The detected reads were filtered to predict circRNAs based on the recommended setting rules (GU/AG flanking the splice sites, clear breakpoint detection; ≤ 2 mismatches in the extension procedure; The length of the circRNA junctions ≤ 100 kb) [28].

Differential expression analysis of circRNAs

Differential expression analysis of circRNAs under CK and LN conditions was performed using the DEseq R package. CircRNAs with P value ≤ 0.05 along with |log2 (foldchange)| ≥ 1 were defined as DECs [29, 30].

Bioinformatics analysis

CircRNA-miRNA interactions were predicted by using the psRNATarget software [31]. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed on the DEC-host genes with the GOseq R packages based on the Wallenius non-central hyper-geometric distribution [32]. IBM SPSS statistics 21 software was used to determine the statistical significance of the data.

Quantitative real-time PCR and data analysis

A set of divergent primers were designed based on the flanking sequences of head-to-tail splicing sites of circRNAs to confirm and quantify the circRNAs predicted in this study (Additional file 1: Table S1). The primers used for the quantitative analysis of the circRNA-host genes were designed using the Primer 5.0 software and listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. The cDNA samples were used as templates and mixed with primers and SYBR Green PCR Real Master Mix (Tiangen, China) for real-time PCR analysis using a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, USA). The temperature procedure was: 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 15 s. TaActin was used as a reference gene to normalize the expression level of investigated genes. IBM SPSS statistics 21 software was used to determine the statistical significance of the data.

Results

Root phenotypes under control and low nitrogen conditions

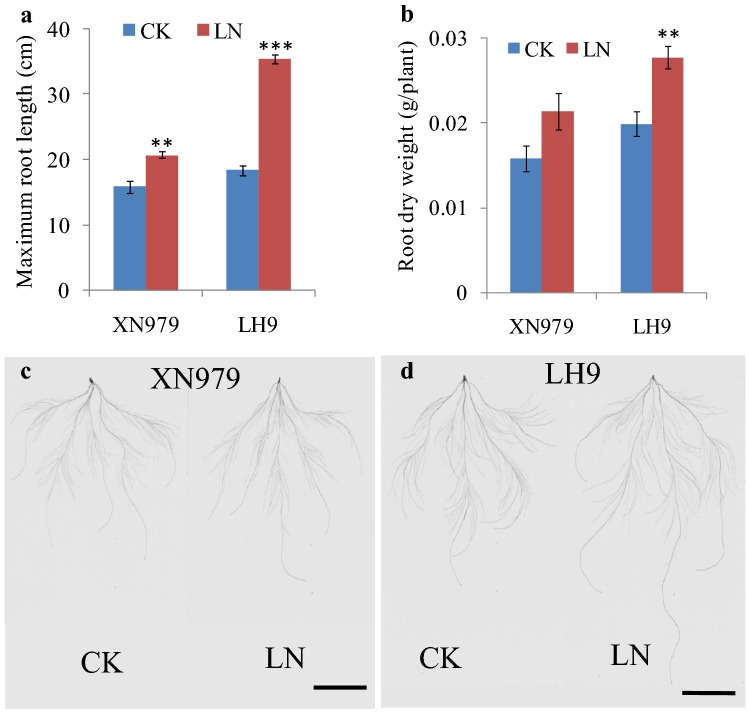

There existed significant genotypic differences of the induction effect between LH9 and XN979. The MRL of XN979 was 4.9 cm longer than control (CK) under LN condition, while the MRL of LH9 was 16.9 cm longer than CK (Fig. 1a–c). Similarly, there was no obvious difference of the RDW of XN979 under LN and CK conditions, while the RDW of LH9 under LN condition was significantly higher than that of CK (Fig. 1b). These results indicated that the root growth of LH9 was more significantly promoted by LN stress than that of XN979.

Fig. 1.

The response of the roots of XN979 and LH9 to low nitrogen (LN) stress. The maximum root length (a), root dry weight (b) and root morphology (c) of XN979 and LH9 under CK (2.0 mM NO3−) and LN (0.1 mM NO3−) conditions. Bar = 5 cm

CircRNAs identification

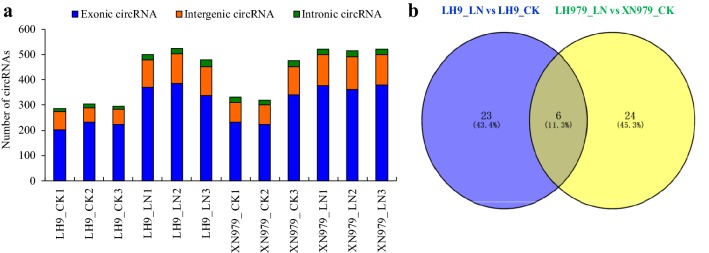

To determine circRNAs involved in the processes of LN response and LN-promoted root growth, cDNA libraries from the roots of LH9 and XN979 under CK and LN conditions were constructed and sequenced. Over 100 million raw reads were generated in each library (among 100.9–101.8 million raw reads in each library). About 80–85% reads were mapped to wheat genome and 15–20% unmapped reads were left for circRNAs prediction using find_circ software. The number of circRNAs identified in each sample ranged from 285 to 522, with over 70% of circRNAs being exonic circRNAs (Fig. 2a). The proportion of intergenic circRNA in each sample was between 18.7 and 25.3%. However, the proportion of intronic circRNAs in each sample was no more than 6.5% (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Statistical analysis of circRNAs and differentially expressed circRNAs (DECs) in the roots of LH9 and XN979 under control (CK) and low nitrogen (LN) conditions. a The number of exonic circRNAs, intergenic circRNAs, and intronic circRNAs in each sequenced sample. b Venn diagram analysis of DECs in the LH9_LN-LH9_CK and XN979_LN-XN979_CK comparisons

Identification of differentially expressed circRNAs

In the one to one comparison between LH9_LN and LH9_CK, 29 circRNAs were defined as DECs (P value ≤ 0.05 along with |log2 (foldchange)| ≥ 1). Among them, 27 circRNAs were up-regulated and two were down-regulated in LH9_LN compared with LH9_CK (Additional file 2: Table S2). In the XN979_LN-XN979_CK comparison, a total of 30 DECs were identified. Among them, 25 circRNAs exhibited up-regulation and five showed down-regulation in the roots of XN979 under LN conditions compared with CK (Additional file 3: Table S3). Among the DECs identified above, 23 DECs were specifically found in the LH9_LN-LH9_CK comparison, 24 DECs were specifically found in the XN979_LN-XN979_CK comparison, and six were present in both comparisons (Fig. 2b; Table 1). Since the degree of LN-promoted root growth is much more pronounced in LH9 than in XN979, the unique DECs in LH9 are likely to play key roles in LN-promoted root growth.

Table 1.

List of identified circRNAs involved in the regulation of low nitrogen-promoted root growth

| CircRNA ID | Position | Chr | Corresponding miRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|

| CircRNA1023 | 1A:24,294–46,159 | TGACv1_scaffold_019564_1AS | tae-miR9660-5p; tae-miR9657b-5p; tae-miR9773; tae-miR1134; tae-miR1133 |

| CircRNA1120 | 1B:17,689–34,357 | TGACv1_scaffold_031043_1BL | tae-miR1117; tae-miR1131 |

| circRNA1393 | 2B:33,405–113,403 | TGACv1_scaffold_146256_2BS | tae-miR9667-5p; tae-miR9652-5p; tae-miR9773; tae-miR9777; tae-miR9772 |

| CircRNA998 | 5A:6372–31,156 | TGACv1_scaffold_374926_5AL | tae-miR1127b-3p; tae-miR1128; tae-miR1135; tae-miR1137b-5p; tae-miR9653a-3p; tae-miR6197-5p; tae-miR1121; tae-miR5049-3p; tae-miR1133; tae-miR1137a; tae-miR9652-5p; tae-miR9773; tae-miR9655-3p |

| CircRNA866 | 5B:48,171–103,123 | TGACv1_scaffold_404448_5BL | tae-miR7757-5p; tae-miR9663-5p; tae-miR1134; tae-miR1120a; tae-miR9670-3p; tae-miR9773; tae-miR9655-3p; tae-miR1133; tae-miR530; tae-miR9677a |

| CircRNA1525 | U:31,407–76,069 | TGACv1_scaffold_642737_U | tae-miR9772; tae-miR9657b-5p; tae-miR9667-5p |

| CircRNA362 | U:19,588–25,979 | TGACv1_scaffold_641443_U | tae-miR9780; tae-miR1134; tae-miR9677b; tae-miR9773 |

| CircRNA1168 | 1A:1774–5928 | TGACv1_scaffold_019820_1AS | – |

| CircRNA977 | 2A:17,304–20,041 | TGACv1_scaffold_113232_2AS | – |

| CircRNA1198 | 2B:82,049–141,309 | TGACv1_scaffold_146009_2BS | – |

| CircRNA907 | 2B:90,859–146,604 | TGACv1_scaffold_129685_2BL | – |

| CircRNA1150 | 2D:14,143–17,119 | TGACv1_scaffold_178493_2DS | – |

| CircRNA1272 | 2D:143,637–155,279 | TGACv1_scaffold_158033_2DL | – |

| CircRNA1539 | 3D:29,228–32,651 | TGACv1_scaffold_249219_3DL | – |

| CircRNA 347 | 4A:40,570-50,497 | TGACv1_scaffold_289349_4AL | – |

| CircRNA806 | 4D:50,956–70,562 | TGACv1_scaffold_343287_4DL | – |

| CircRNA982 | 4D:50,956–70,635 | TGACv1_scaffold_343287_4DL | – |

| CircRNA765 | 5A:65,727–70,950 | TGACv1_scaffold_375076_5AL | – |

| CircRNA1360 | 5B:1241–13,921 | TGACv1_scaffold_404200_5BL | – |

| CircRNA962 | 6A:77,022–79,083 | TGACv1_scaffold_485269_6AS | – |

| CircRNA1683 | 6A:77,371–794,321 | TGACv1_scaffold_485269_6AS | – |

| CircRNA1258 | 5D:36,358–43,165 | TGACv1_scaffold_434846_5DL | – |

| CircRNA910 | U:88–71,065 | TGACv1_scaffold_641580_U | – |

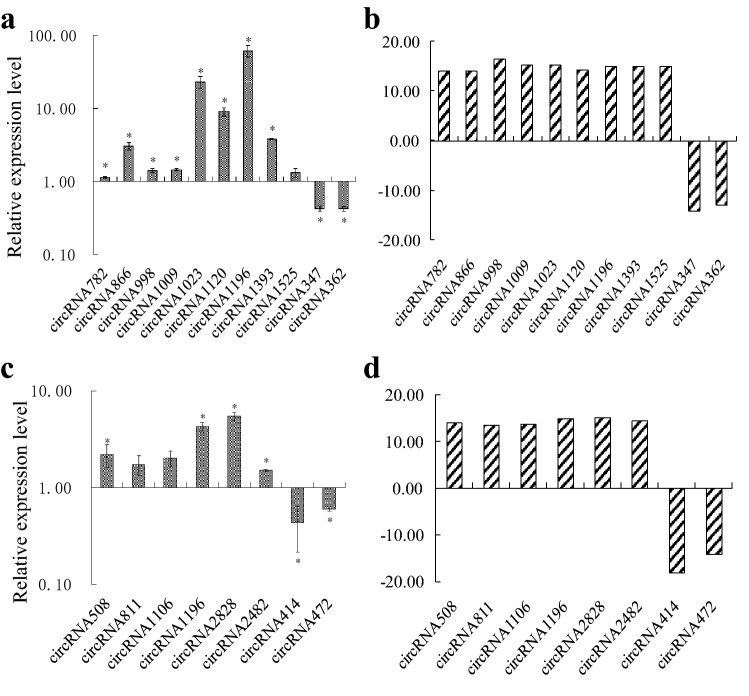

Real-time PCR analysis of DECs and DEC-host genes

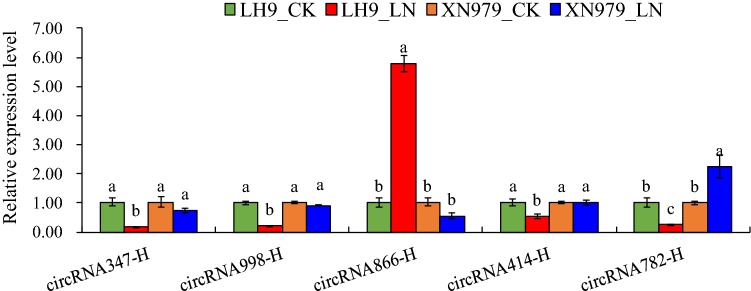

To verify the data of RNA-seq, 11 DECs identified in the LH9_LN-LH9_CK comparison and 8 DECs identified in the XN979_LN-XN979_CK comparison were randomly selected for expression level verification using real-time PCR (Fig. 3). The expression levels of the 29 DECs detected using real-time PCR technology matched well with the results of RNA-seq. This evidence indicated that the results of RNA-seq are reliable. It has been reported that the expression levels of many plant circRNAs showed positive or negative correlations with their DEC-host genes [13, 14]. We selected five DECs including three LH9 unique, one XN979 unique and one common responsive DECs in both varieties to check the expression levels of the DEC-host genes. Results showed that the expression levels of four DECs-host genes showed a positive or negative correlation with their corresponding DECs. However, we did not observe the correlation between the expression levels of circRNA414 and its host gene in XN979 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Relative expression analysis of circRNAs under control (CK) and low nitrogen (LN) conditions. a, b The results of relative expression analysis of LH9 under CK and LN conditions by using real-time PCR (a) and RNA-sequence (b) technologies, respectively. c, d The results of relative expression analysis of XN979 under CK and LN conditions by using real-time PCR (c) and RNA-sequence (d) technologies, respectively; Each bar shows the mean ± standard errors (SE) of three replicates. (*P < 0.05, Duncan’s multiple range test)

Fig. 4.

Relative expression analysis of circRNA-host genes in the roots of LH9 and XN979 under control (CK) and low nitrogen (LN) conditions. CircRNA347-H, circRNA998-H, circRNA866-H, circRNA414-H and circRNA782-H represent the host genes of circRNA347, circRNA998, circRNA866, circRNA414 and circRNA782, respectively. Significant difference at < 0.05 is indicated by different letters above the columns

GO analysis of DECs-host genes of LH9 unique DECs

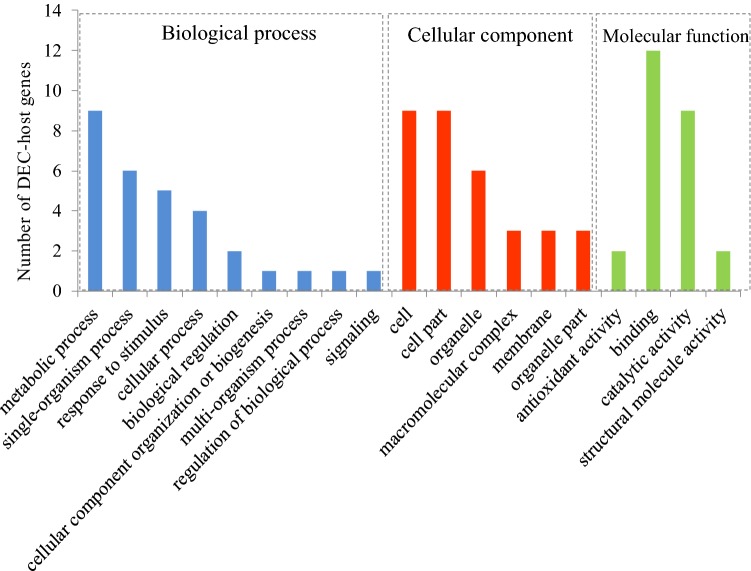

To further understand the functions and features of the specifically identified DECs in LH9, the gene ontology (GO) database was adopted to categorize the DECs-host genes. Those DECs-host genes were mainly classified into 19 important functional groups including 9 biological processes, 6 cellular components and 4 molecular functions (Fig. 5). According to the biological process properties, the most abundant term was “metabolic process” with 9 DEC-host genes. GO terms related to biological regulation, responses to stimuli and signalling were also significantly enriched. In the cellular component category, “cell” (9 DEC-host genes) and “cell part” (9 DEC-host genes) were the central categories. The “binding” and “catalytic activity” included 12 and 9 DECs-host genes, respectively, and were the two most dominant terms in molecular function category (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Gene Ontology analysis of the host genes of the differentially expressed circRNAs (DECs) that specifically identified in LH9. Columns in blue color represent GO terms belonging to the biological process category; Columns in red color represents GO terms belonging to the cellular component category; Columns in green color represents GO terms belonging to the molecular function category

The regulation of circRNAs acting as miRNA sponges

Studies have demonstrated that circRNAs could bind miRNAs and act as competing endogenous RNAs of miRNAs [14, 28]. That is, circRNAs could affect gene post-transcriptional regulation by binding to miRNAs and preventing them from regulating their target mRNAs. To detect whether the unique DECs in LH9 can perform similar functions, psRNATarget software was employed to predict potential miRNA binding sites. Ultimately, seven out of the 23 circRNAs were predicted to have two to thirteen corresponding miRNAs binding sites (Table 1).

Discussion

CircRNAs were once considered to be transcriptional noises in eukaryotes [28]. However, in recent years, they have been proved to be widespread in plants and play important roles in regulating plant growth, development and responding to abiotic stresses [13–25]. Next-generation sequencing technology combined with bioinformatics methods allows us to genome-wide explore circRNAs. Low nitrogen availability limits plant shoot growth, while it promotes the growth of primary and lateral roots, enabling the root system to reach deeper layers of the soil [1, 3, 33]. In wheat, the growth of roots is also promoted by LN stress, but there are significant genotypic effects [34]. In this study, LN stress significantly increased the RDW and MRL of wheat cultivar LH9, but the effects on XN979 were much smaller (Fig. 1). Here, an integrated comparative root transcriptome study of LH9 and XN979 was conducted under CK and LN conditions to explore LN stress responsive circRNAs in hexaploid wheat. Hundreds of circRNAs were identified in each sample. Most of them belong to exonic circRNAs, followed by intergenic circRNAs, and the lowest proportion is intronic circRNAs (no more than 6.5%) (Fig. 2a). The proportion of intronic circRNAs is similar to the results of other reports in Arabidopsis (3.8% intronic circRNAs) and tomato (3.6%) [16, 19]. Like other stresses, such as heat shock in Arabidopsis [14], chilling in tomato and dehydration in wheat [19, 23], LN stress also altered the expression profiles of circRNA in wheat. In total, we identified 29 and 30 LN-responsive circRNAs in LH9 and XN979, respectively, of which six co-existed in both varieties (Fig. 2b). There were 23 DECs specifically existed in the LH9_LN-LH9_CK comparison (Fig. 2b). As has been mentioned above, the degree of LN-promoted root growth in LH9 is much more pronounced than that of XN979. Therefore, the six and 23 DECs may involve in the processes of common response to LN stress and LN-promoted root growth, respectively. It has been reported that the expression levels of many plant circRNAs showed positive or negative correlations with their host genes [13, 14]. Pan et al. reported that about 70% of 439 circRNAs were expressed in a similar pattern with their host genes after heat shock in Arabidopsis [14]. Our results also showed that the expression levels of four out of five DECs-host genes showed a positive or negative correlation with their corresponding circRNAs (Fig. 4). The result is basically consistent with previous study [14]. However, the identified DEC-host genes in this study are still functionally unknown. To understand further the functions of the unique DECs, GO analysis was performed to annotate the biological functions of the DEC-host genes in LH9. Some important terms related to biological regulation, responses to stimuli and signalling were significantly enriched (Fig. 5). These processes may participate in the regulation of LN-promoted root growth.

Although the mechanism of how plant circRNAs function remains to be elucidated, studies in animal and human have confirmed that circRNAs can act as miRNA sponges, trapping miRNAs from its target genes via the ceRNA network [35, 36]. To uncover whether circRNAs in wheat could target miRNAs and involve in the post-transcriptional regulation of genes, psRNATarget software was used to identify potential miRNAs binding sites of the DECs. Seven of the 23 LH9-specific DECs had putative miRNA-binding sites (Table 1). Moreover, all the seven DECs had 2–13 miRNA-binding sites, which was similar with previous reports in human and another study in wheat [23, 26], but was significantly higher than that reported in rice and tomato [18, 19]. Interestingly, some putative circRNA-binding miRNAs have been reported that involved in the response to low nitrogen and other abiotic stresses [37, 38]. For example, miR530 is differentially expressed in response to low nitrogen stress in rice, suggesting that it may play an important role in plant nitrogen utilization [37]. Another miRNA, miR1120a, has been reported that involved in salt stess response [38]. However, none of them have been reported involved in the regulation of LN-promoted root growth. Therefore, although circRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation might play an important role in the regulation of LN-promoted root growth, there is still a lot of work to be done to clarify how it plays the regulatory role.

Conclusions

LN stress altered the expression profiles of circRNAs in wheat. We totally identified six circRNAs involved in the common response to LN stress and 23 circRNAs involved in the regulation of LN-promoted root growth. Some of them might act as miRNA sponges, trapping miRNAs from its target genes via the ceRNA network. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the identification of LN responsive circRNAs in plants. Our results provided clues for investigating the functions of circRNAs in response to LN stress and the regulation of LN-promoted root growth in wheat.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers used for real-time PCR.

Additional file 2: Table S2. List of differentially expressed circRNAs (DECs) in the LH9_LN-LH9_CK comparison.

Additional file 3: Table S3. List of differentially expressed circRNAs (DECs) in the XN979_LN-XN979_CK comparison.

Authors’ contributions

HY and YR performed most of the experiments; LL and YX took part in partial work of this research; ZX and ZW gave many advices during the research; YR and TL conceived and designed the experiments; YR wrote the paper. TL gave many helpful suggestions on the writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31572197), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0300205), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31201678), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan province (162300410133) and the State Key Laboratory Program (PCCE-KF-2017-04).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- LN

low nitrogen

- DECs

differentially expressed circRNAs

- rRNA

ribosomal RNAs

- GO

gene ontology

Contributor Information

Yongzhe Ren, Email: yongzheren66@163.com.

Huifang Yue, Email: yuehf1991@163.com.

Le Li, Email: 1624254991@qq.com.

Yanhua Xu, Email: yanhuaxu66@163.com.

Zhiqiang Wang, Email: wzq78@163.com.

Zeyu Xin, Email: mrxxtz@163.com.

Tongbao Lin, Email: linlab@163.com.

References

- 1.Linkohr BI, Williamson LC, Fitter AH, Leyser HM. Nitrate and phosphate availability and distribution have different effects on root system architecture of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;29:751–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochholdinger F, Tuberosa R. Genetic and genomic dissection of maize root development and architecture. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruber BD, Giehl RF, Friedel S, von Wirén N. Plasticity of the Arabidopsis root system under nutrient deficiencies. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:161–179. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.218453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch JP, Chimungu JG, Brown KM. Root anatomical phenes associated with water acquisition from drying soil: targets for crop improvement. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:6155–6166. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt JE, Gaudin ACM. Toward an integrated root ideotype for irrigated systems. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasda E, Parker R. Circular RNAs: diversity of form and function. RNA. 2014;20:1829–1842. doi: 10.1261/rna.047126.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen LL, Yang L. Regulation of circRNA biogenesis. RNA Biol. 2015;12:381–388. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salzman J, Gawad C, Wang PL, Lacayo N, Brown PO. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeck WR, Sharpless NE. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:453–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westholm JO, Miura P, Olson S, Shenker S, Joseph B, Sanfilippo P, Celniker SE, Graveley BR, Lai EC. Genome-wide analysis of Drosophila circular RNAs reveals their structural and sequence properties and age-dependent neural accumulation. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1966–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan XY, Zhang XN, Wu XL, Guo HS, Hu YQ, Tang FC, Huang YY. Single-cell RNA-seq transcriptome analysis of linear and circular RNAs in mouse preimplantation embryos. Genome Biol. 2015;16:148. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0706-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sablok G, Zhao H, Sun X. Plant circular RNAs (circRNAs): transcriptional regulation beyond miRNAs in plants. Mol Plant. 2016;9:192–194. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye CY, Chen L, Liu C, Zhu QH, Fan L. Widespread noncoding circular RNAs in plants. New Phytol. 2015;208:88–95. doi: 10.1111/nph.13585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan T, Sun XQ, Liu YX, Li H, Deng GB, Lin HH, Wang SH. Heat stress alters genome-wide profiles of circular RNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2018;96:217–229. doi: 10.1007/s11103-017-0684-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu TF, Zhang L, Chen G, Shi TL. Identifying and characterizing the circular RNAs during the lifespan of Arabidopsis leaves. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1278. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen G, Cui JW, Wang L, Zhu YF, Lu ZG, Jin B. Genome-wide identification of circular RNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1678. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao W, Cheng YH, Zhang C, You QB, Shen XJ, Guo W, Jiao YQ. Genome-wide identification and characterization of circular RNAs by high throughput sequencing in soybean. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5636. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05922-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu TT, Cui LL, Zhou Y, Zhu CR, Fan DL, Gong H, Zhao Q, Zhou CC, Zhao Z, Lu DF, et al. Transcriptome-wide investigation of circular RNAs in rice. RNA. 2015;21:2076–2087. doi: 10.1261/rna.052282.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuo J, Wang Q, Zhu B, Luo Y, Gao L. Deciphering the roles of circRNAs on chilling injury in tomato. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;479:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darbani B, Noeparvar S, Borg S. Identification of circular RNAs from the parental genes involved in multiple aspects of cellular metabolism in barley. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:776. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao T, Wang L, Li S, Xu M, Guan X, Zhou B. Characterization of conserved circular RNA in polyploid Gossypium species and their ancestors. FEBS Lett. 2017;591:3660–3669. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, Zhang P, Fan Y, Lu Q, Li Q, Yan J, Muehlbauer GJ, Schnable PS, Dai M, Li L. Circular RNAs mediated by transposons are associated with transcriptomic and phenotypic variation in maize. New Phytol. 2017;217:1292–1306. doi: 10.1111/nph.14901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang YX, Yang M, Wei SM, Qin FJ, Zhao HJ, Suo B. Identification of circular RNAs and their targets in leaves of Triticum aestivum L. under dehydration stress. Front Plant Sci. 2017;7:2024. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.02024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang PL, Bao Y, Yee MC, Barrett SP, Hogan GJ, Olsen MN, Dinneny JR, Brown PO, Salzman J. Circular RNA is expressed across the eukaryotic tree of life. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang ZP, Liu YF, Li DW, Li L, Zhang Q, Wang SB, Huang HW. Identification of circular RNAs in kiwifruit and their species-specific response to bacterial canker pathogen invasion. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:413. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren YZ, He X, Liu DC, Li JJ, Zhao XQ, Li B, Tong YP, Zhang AM, Li ZS. Major quantitative trait loci for seminal root morphology of wheat seedlings. Mol Breed. 2012;30:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s11032-011-9605-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zadoks JC, Chang TT, Konzak CF. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Res. 1974;14:415–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.1974.tb01084.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer M, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou L, Chen JH, Li ZZ, Li XX, Hu XD, Huang Y, Zhao XK, Liang CZ, Wang Y, Sun L, et al. Integrated profiling of microRNAs and mRNAs: microRNAs located on Xq27.3 associate with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dai X, Zhao PX. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W155. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young MD, Wakefeld MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynch JP. Steep, cheap and deep: an ideotype to optimize water and N acquisition by maize root systems. Ann Bot. 2013;112:347–357. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren YZ, Qian YY, Xu YH, Zou CQ, Liu DC, Zhao XQ, Zhang AM, Tong YP. Characterization of QTLs for root traits of wheat grown under different nitrogen and phosphorus supply levels. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:2096. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK, Kjems J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang S, Zhu D, Li H, Li H, Feng C, Zhang W. Characterization of circRNA-associated-ceRNA networks in a senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 brain. Mol Ther. 2017;25:2053–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai H, Lu Y, Xie W, Zhu T, Lian X. Transcriptome response to nitrogen starvation in rice. J Biosci. 2012;37:731–747. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feng K, Nie X, Cui L, Deng P, Wang M, Song W. Genome-wide identification and characterization of salinity stress-responsive miRNAs in wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides) Genes. 2017;8:156. doi: 10.3390/genes8060156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primers used for real-time PCR.

Additional file 2: Table S2. List of differentially expressed circRNAs (DECs) in the LH9_LN-LH9_CK comparison.

Additional file 3: Table S3. List of differentially expressed circRNAs (DECs) in the XN979_LN-XN979_CK comparison.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.