Abstract

Objectives. To illustrate the magnitude of between-state heterogeneities in tuberculosis (TB) incidence among US populations at high risk for TB that may help guide state-specific strategies for TB elimination.

Methods. We used data from the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System and other public sources from 2011 to 2015 to calculate TB incidence in every US state among people who were non–US-born, had diabetes, or were HIV-positive, homeless, or incarcerated. We then estimated the proportion of TB cases that reflected the difference between each state’s reported risk factor–specific TB incidence and the lowest incidence achieved among 4 states (California, Florida, New York, Texas). We reported these differences for the 4 states and also calculated and aggregated across all 50 states to quantify the total percentage of TB cases nationally that reflected between-state differences in risk factor–specific TB incidence.

Results. On average, 24% of recent TB incidence among high-risk US populations reflected heterogeneity at the state level. The populations that accounted for the greatest percentage of heterogeneity-reflective cases were non–US-born individuals (51%) and patients with diabetes (24%).

Conclusions. State-level differences in TB incidence among key populations provide clues for targeting state-level interventions.

The United States experienced an average annual decline in tuberculosis (TB) incidence of more than 5% from 1993 to 2014.1 However, between 2014 and 2016, TB incidence remained essentially flat, at approximately 3.0 cases per 100 000 people per year.2 To better understand trends and continue progress toward elimination (< 1 case/million people/year),3 it may be useful to identify heterogeneities in TB incidence between states among high-risk populations.4 Describing the magnitude of such heterogeneity by specific risk factors can provide insights for officials to tailor TB control and prevention activities to the unique public health requirements of each state. Some sources of observed heterogeneity may be unmodifiable, but other components may be actionable. These results can inform state-level investigations and help develop effective targeted interventions.

We therefore sought to quantify the differences in TB incidence within selected populations in all 50 US states, benchmarked against TB incidence in 1 of 4 states (California, Texas, New York, Florida). These 4 states currently account for more than half of all new TB cases in the United States and contain large and heterogeneous populations at high risk for TB disease relative to most other states.

METHODS

We used incident TB case data reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System from 2011 to 2015 for the 50 US states and the District of Columbia.5 We focused on key populations comprising persons who were reported to be (1) non–US-born (by region: Europe, Africa, Asia, the Americas), (2) diabetic, (3) homeless in the past 12 months, (4) incarcerated, and (5) HIV-positive. We estimated TB incidence in each key population for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Given differences in the availability of denominator data for key populations by year, we calculated risk factor–specific TB incidence using a ratio of mean values across multiple years of data. This method ensures that numerators (cases) and denominators (population) are on the same scale when years are missing in either one.

We obtained mean annual estimates of each key population size for the 50 US states including the District of Columbia from several sources. Estimates of non–US-born populations were obtained from the American Community Survey for the years 2011 to 2015, stratified by region of birth.6 We estimated diabetic population sizes from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System for 2011 to 2015.7 We used the Annual Homeless Assessment Report by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development from 2013 to 2015 to determine the size of the homeless population.8 We estimated incarcerated population sizes from the US Bureau of Justice statistics from 2011 to 2015.9 We obtained HIV-positive population estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention AtlasPlus database from 2010 to 2014.10 Details are included in Appendix A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

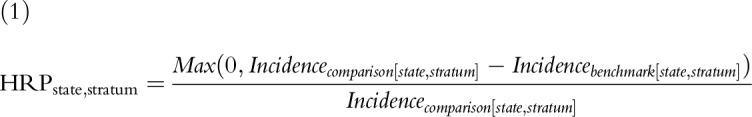

After calculating state and risk factor–specific TB incidence for all 50 states and the District of Columbia, we calculated the number of cases expected to occur in every state if the risk factor–specific incidence of TB in that state were lowered to a benchmark value (set to the lowest risk factor–specific TB incidence in California, Texas, New York, Florida). We began by calculating the difference between the mean incidence for each risk factor (stratum) in a comparison state and the mean incidence for the same stratum and time period in the benchmark state. We divided this difference by the mean incidence in the comparison state to determine the heterogeneity-reflective proportion (HRP) of incidence in that state (Equation 1):

|

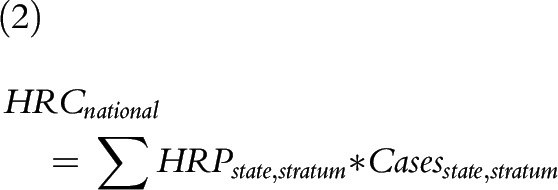

We multiplied the number of reported incident TB cases in each comparison state by the state- and stratum-specific estimate of HRP to determine the number of heterogeneity-reflective cases (HRCs) that reflected the differences in incidence by state and stratum. We then summed these HRCs across all states and strata to provide a national estimate of the number of recent TB cases that reflected state-level heterogeneity (Equation 2):

|

RESULTS

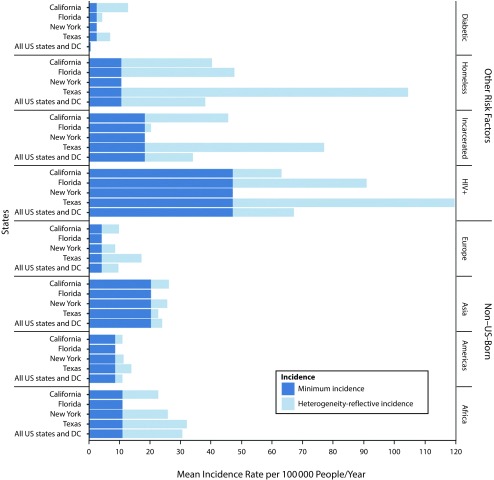

Figure 1 presents summary TB measures by population risk factors, 4 benchmark states, and nationally. Among the 4 states considered as potential benchmarks, Florida had the lowest incidence for all non–US-born populations and for patients with diabetes, whereas New York reported the lowest incidence for homeless, HIV-positive, and incarcerated populations. In considering only these 4 states, Texas had the highest percentage of heterogeneity-reflective TB incidence among those born in Europe, the Americas, and Africa at 76%, 37%, and 66% of total TB incidence by risk factor, respectively. California reported the highest percentage of heterogeneity-reflective incidence among Asian-born populations (22%) and patients with diabetes (81%). Texas also reported the highest percentage of heterogeneity-reflective incidence among populations who were homeless (90%), incarcerated (76%), and HIV-positive (61%).

FIGURE 1—

Mean Tuberculosis Incidence per 100 000 People, by Population Risk Factors, 4 Example States, and Nationally: United States, 2011–2015

Note. These estimates were calculated as mean values over the years 2011–2015 (2010–2014 for the HIV-positive risk group and 2011–2015 for patients with diabetes in NY) and stratified by state and risk factor. Incidence rates corresponding to the minimum risk group–specific incidence among the 4 most populous US states (CA, TX, NY, and FL) are shown in dark blue, whereas heterogeneity-reflective annual incidence rates (i.e., those higher than the minimum risk group–specific incidence) are shown in light blue.

After calculating and converting heterogeneity-reflective incidence values to cases for all 50 US states and the District of Columbia, we estimated that the total number of heterogeneity-reflective cases constituted 24% of all TB cases observed nationwide from 2011 to 2015. The largest percentage of these cases occurred among non–US-born individuals (51%) and patients with diabetes (24%). Approximately 59% of these heterogeneity-reflective cases occurred in Florida, Texas, New York, or California. Figures A and B in Appendix A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.) illustrate the case distribution by risk factor by the 4 example states and by all 50 states plus the District of Columbia, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Advancing toward elimination of TB in the United States will require identifying where substantial progress can be made and applying innovative solutions targeted to priority populations at the state level.11 Understanding the magnitude of heterogeneity among populations at high risk in neighboring or demographically similar states may encourage state-level TB decision-makers to engage in discussions about differences in programmatic efforts to conduct TB testing and treatment in populations at highest risk for TB disease.

This analysis suggests that 24% of all incident TB cases in the United States—more than 2200 cases annually—reflect state-level heterogeneity. To the extent that between-state differences indicate potential for reducing TB incidence through targeted efforts, these results also may suggest the magnitude of achievable savings. If each case incurs a societal cost of $44 000 (in 2014 US dollars and not considering additional costs of multidrug resistance),12 then targeted prevention efforts could reduce TB treatment costs by approximately $100 million per year.

These results should be interpreted with caution given the ecological nature of this analysis. We used survey data from multiple sources to estimate population denominators, and our analysis relied on the study design and methods of those surveys for accurate estimates. Because we lacked population data on individuals contributing to multiple risk categories, our estimate of cases reflecting heterogeneity did not account for such population overlap. State-level differences in TB incidence among populations at high risk also may reflect several modifiable and unmodifiable factors, as well as differences in surveillance definitions among jurisdictions in reporting of TB risk factors. In the absence of data on the distributions of these covariates at the state level, this analysis implicitly assumed that the distributions of other known TB risk factors between states were similar (e.g., sex and age).

In summary, we estimate that nearly one quarter of all incident TB cases in the United States from 2011 to 2015 reflected state-level differences in TB incidence among key populations. These estimates can help target TB prevention efforts at the state level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention Epidemiologic and Economic Modeling Agreement (U38PS004646), the National Institutes of Health (grants R01HD068395, R21HD075662, R24HD042828), and the Emory Center for AIDS Research (grant P30AI050409).

We thank members of the scientific and public health advisory groups of the Coalition for Applied Modeling for Prevention project for their input on this study, and specifically those members who reviewed a previous version of this article: Jonathon Poe and Kristen St. John. We also would like to thank Adam Readhead from the California Department of Public Health for his thoughtful comments regarding the analysis and framing of this article.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional review board approval was not required for this analysis of national surveillance data. US state and local health departments report tuberculosis cases to the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System under an assurance of confidentiality.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2014. 2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/reports/2014/table5.htm. Accessed September 2, 2017.

- 2.Schmit KM, Wansaula Z, Pratt R, Price SF, Langer AJ. Tuberculosis - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(11):289–294. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6611a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowdle WR. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A strategic plan for the elimination of tuberculosis in the United States. MMWR Suppl. 1989;38(3):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrestha S, Hill AN, Marks SM, Dowdy DW. Comparing drivers and dynamics of tuberculosis in California, Florida, New York, and Texas. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(8):1050–1059. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0377OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2011-2015. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Census Bureau. American Community Survey Web site. 2016. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/download_center.xhtml. Accessed August 3, 2017.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States Diabetes Surveillance System: diagnosed diabetes. 2017. Available at: https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/diabetes/DiabetesAtlas.html. Accessed August 3, 2017.

- 8.US Department of Housing and Urban Development. One year estimates of homelessness: 2013-2015. 2015. Available at: https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2015-AHAR-Part-1.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 9.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Data collection: National Prisoner Statistics Program: Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) - prisoners. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=nps. 2016. Accessed August 3, 2017.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. AtlasPlus Web site. Available at: https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/nchhstpatlas/main.html. 2017. Accessed August 3, 2017.

- 11.Hill AN, Becerra JE, Castro KG. Modelling tuberculosis trends in the USA. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(10):1862–1872. doi: 10.1017/S095026881100286X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro KG, Marks SM, Chen MP et al. Estimating tuberculosis cases and their economic costs averted in the United States over the past two decades. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;20(7):926–933. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]