Abstract

Objective

Trauma exposure is common during childhood and adolescence and is associated with youth emotional and behavioral problems. The present study adds to the current literature on trauma exposure among adolescent clinical populations by examining the association between trauma exposure and adolescent self-report of emotional and behavioral problems broadly, including internalizing and externalizing symptoms, in addition to the trauma-specific symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Method

This study included 94 female (64%) and male (36%) adolescents, ages 13–19, representing four clinical populations: those seeking 1) inpatient psychiatry, 2) outpatient psychiatry, 3) residential substance abuse, and 4) outpatient medical services. Adolescents self-reported trauma history, internalizing, externalizing, and PTSD symptoms.

Results

The majority of adolescents reported experiencing at least one traumatic event (83%; M = 2.28, SD = 1.83). Multiple regression analyses controlling for age, race/ethnicity, gender, and treatment setting indicated a greater number of types of trauma is associated with externalizing symptoms (β= .31, p <.01) and PTSD symptoms (β = .35, p < .01).

Conclusion

Trauma is a common experience among adolescents, particularly those presenting for behavioral health services, making trauma-informed care essential in these service delivery settings. Treatment that addresses adolescent risk behaviors and prevents recurrent trauma may be particularly important given the negative impact of multiple traumatic events on developing adolescents.

Keywords: adolescent, trauma exposure, internalizing, externalizing, posttraumatic stress

Trauma exposure is common during childhood and adolescence and associated with youth emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, delinquency, substance abuse, suicidality, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD); Kendall-Tackett, Finkelhor, & Steinberg, 1993; Kessler, 2000; Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Layne et al., 2014) as well as negative physical and mental health outcomes throughout adulthood (e.g., anxiety, depression, health risk behavior, disease, and premature death; Brown & McNiff, 2009; Felitti et al., 1998; Green et al., 2010). Recent published research spearheaded by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) indicates experiencing multiple types of trauma is related to various emotional and behavioral problems among youth seeking behavioral health services; however this work has largely relied on parent/caregiver or other adult report (e.g., clinician; Greeson et al., 2014; Layne et al., 2014). The present study adds to the current literature on trauma exposure among adolescent clinical populations by examining the association between trauma exposure and adolescent self-report of emotional and behavioral problems broadly, including internalizing and externalizing symptoms, in addition to the trauma-specific symptoms of PTSD.

Prevalence of Adolescent Trauma Exposure

In a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents ages 13 to 17 years old, 62% had been exposed to at least one lifetime traumatic event and 19% had been exposed to three or more traumatic events (McLaughlin et al., 2013). Youth most frequently encounter traumatic events such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing domestic violence (Begle et al., 2011; Cisler et al., 2012; Cloitre et al., 2009; Greeson et al., 2014; Kendall-Tackett et al., 1993; Layne et al., 2014; Wamser-Nanney & Vandenberg, 2013). Experiencing multiple types of trauma (e.g., abuse, community violence, natural disaster) appears to be common over the course of childhood and even more so over adolescence (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007). For instance, in their national telephone survey study of victimization among youth ages 2 – 17 years (parent-report for children <10 years old; N = 2030), Finkelhor and colleagues identified an average of 1.7 types of trauma exposures among children ages 2–5, and 3.4 among 14–17 year olds (Finkelhor, Omrod, & Turner, 2009). Research from the NCTSN Core Data set demonstrates that experiencing multiple types of trauma is common among young children ages 1.5 – 5 years (M = 3.19) and youth ages 6–18 years (M = 3.71) seeking behavioral health services (Greeson et al., 2014).

Emotional and Behavioral Problems Associated with Trauma Exposure

A common framework for child and adolescent psychopathology divides emotional and behavioral problems into internalizing and externalizing problems (Achenbach, 1991). Internalizing problems are those with mood or emotion as their primary feature and include such symptoms as anxiety, depression, anhedonia, and withdrawal (Kovacs & Devlin, 1998). Externalizing problems are those such as aggression, delinquency, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder (Achenbach, 1991).

Recent research facilitated by data from the NCTSN indicates adolescent trauma is associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems. For instance, in a study of 3,785 trauma-exposed adolescents ages 13–18 seeking services at NCTSN-affiliated agencies, logistic regression analyses indicated that each additional type of trauma or loss exposure reported by clinicians on a trauma exposure screen (Pynoos et al., 2014) was associated with a greater likelihood of engaging in high risk behavior. High-risk behaviors and the associated increased likelihood were 1) being a victim of sexual exploitation (i.e., exchanging sex for money, drugs, or other resources), 18%, 2) running away from home, 14%, 3) criminal activity, 13%, 4) suicidality, 12%, 5) self-injurious behavior, 11%, 6) alcohol use, 11%, 7) substance abuse, 8%, and 8) skipping school, 6% (Layne et al., 2014).

Greeson and colleagues (2014) also utilized data generated by the NCTSN to examine both internalizing and externalizing problems among trauma-exposed children and adolescents (N = 11,028) using parent report of problems (Child Behavior Checklist; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Findings indicated that each additional type of trauma, measured using the clinician-completed trauma exposure screen, was associated with increased odds (ranging from 1.11 to 1.16) of scoring in the clinical range on all five externalizing subscales (e.g., aggressive behavior, rule breaking). Similarly, each additional type of trauma was associated with increased odds (ranging from 1.07 to 1.15) of scoring in the clinical range on five of six internalizing subscales (e.g., anxious/depressed, thought problems).

PTSD, a constellation of trauma-related affective, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms causing significant impairment or suffering, is a disorder causally related to trauma exposure (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). PTSD includes symptoms that could be classified within the internalizing and externalizing domains; however, diagnostically, PTSD symptoms are assessed in relation to a specific trauma or type of repeated trauma (e.g., nightmares of a car accident or repeated physical abuse, fear and avoidance of trauma reminders, excessive guilt related to the event) and, therefore, only assessed in those reporting trauma exposure.

A recent estimate of lifetime PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV criteria among a national sample of adolescents (N = 6,483, ages 13–17 years) indicates 4.7% of adolescents experience PTSD (McLaughlin et al., 2013). Although PTSD is a relatively infrequent outcome of trauma exposure (Copeland, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, 2007), research suggests adolescents with moderate symptoms that do not meet full diagnostic criteria can still benefit from treatment (CATS Consortium, 2010). Similar to findings related to internalizing and externalizing symptoms, PTSD and posttraumatic symptom complexity is more common among youth who experienced multiple types of trauma (Cloitre et al., 2009; Hodges et al., 2013; McLaughlin et al., 2013).

Study Aims and Hypotheses

The aims of this study were to examine the association between the number of types of trauma exposure and the broad dimensions of self-reported internalizing and externalizing symptoms among adolescents seeking services across a range of medical and behavioral health clinical settings representing four clinical populations (i.e., inpatient psychiatry, outpatient psychiatry, residential substance abuse, and outpatient medical services). Additionally, within the subsample of trauma-exposed adolescents, we examined the association between multiple trauma exposure and PTSD symptom severity. Based on prior research, we hypothesized that a greater number of types of trauma would be associated with both higher internalizing and externalizing symptoms, as well as PTSD symptoms among the adolescents reporting a history of trauma.

Method

Design & Procedure

Data from this study come from a larger cross-sectional psychometric study (Comtois, Voss, & Morgan, 2007). Exclusion criteria included insufficient English language abilities (of the adolescent or parent) to consent, assent, and/or understand the study interview. Additionally, adolescents were excluded if they were experiencing psychotic symptoms, cognitive impairment, distress, or aggressive behavior that interfered with the ability to tolerate study procedures. Adolescents under arrest, in a correctional facility, or in foster care were excluded.

Participants were recruited from four clinical treatment settings in Washington State, including 1) child/adolescent inpatient psychiatric unit (n = 24), 2) child/adolescent outpatient psychiatric clinic (n = 30), 3) a residential substance abuse (SA) treatment center (n = 30), and 4) adolescent general medical clinic (n = 10). Adolescents receiving services were approached by a clinical or medical provider. If the adolescent was interested in participating, the clinical or medical provider facilitated contact with the research team. Adolescents less than 18 years old and guardians/parents provided informed assent and consent, respectively. Adolescents 18 or 19 years old provided consent. Participants were compensated $20 for completing the study. All study procedures were approved by the Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center Institutional Review Board (now Seattle Children’s Hospital) in Seattle, Washington. Data were collected between April and September 2007.

Participants

Participants in this study were adolescents ages 13–19 years old (N = 94; M = 15.64, SD = 1.49), 64% female (n = 60), and 73% White/Caucasian (n = 69).

Measures

Demographic variables obtained during the study interview included age, gender, and race/ethnicity (White n = 69, other or mixed race/ethnicity, n = 16, Asian n = 4, African American, n = 2, Latino/a n = 2, Pacific Islander n = 1; White/Caucasian versus Non-White/Caucasian for use in analyses).

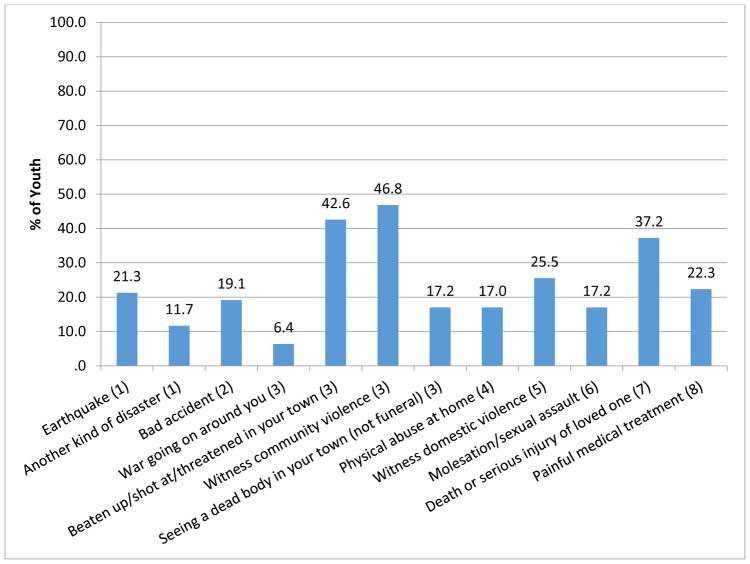

Trauma exposure was assessed using the trauma exposure screening portion of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index (Pynoos, Rodriguez, Steinberg, Stuber, & Frederick, 1998; Steinberg, Brymer, Decker, & Pynoos, 2004). Adolescents indicated whether they had ever experienced one of 12 types of traumatic events. We determined that four of these 12 types could be collapsed to reduce double-counting of what were actually the same types of trauma. Types were collapsed to include: 1) natural disaster 2) accident, 3) community violence, 4) domestic violence, 5) physical abuse, 6) sexual abuse, 7) hearing about serious injury/death of a loved one, and 8) painful or scary medical treatment (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percent of youth reporting experiencing each trauma history screening item on the UCLA PTSD Index Revised (Pynoos, et al., 1998). Screening items were further classified into 8 categories for use in analyses as denoted in parentheses.

Internalizing and externalizing symptoms were measured using the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, 1991), a self-report measure using 103 questions about current problems rated on a Likert scale (0 = Not True, 1= Somewhat or Sometimes True, 2= Very True or Often True). The YSR is normed for use with children and adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years old (18 year old norms were used for 19 year old participants). The internalizing sub-scale includes symptoms related to Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Somatic Complaints. The externalizing sub-scale includes symptoms related to Aggressive Behavior and Rule-Breaking Behavior. The symptom scores are provided in t-scores (standardized scores), with a clinical range cut-off score of >70. The YSR has well-established reliability and validity in numerous psychometric studies (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

PTSD symptom severity was assessed using the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index (RI) – Revised (Steinberg et al., 2004), which assess symptoms according to DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnostic criteria in relation to one of the traumatic events identified in the screening measure. Adolescents self-reported how much of the time they have been bothered by 17 symptoms during the previous month on a severity scale from None (0) to Most (4). Scores were summed and higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. Scores ≤ 24 indicated low, 25–37 moderate, and ≥ 38 high, symptom severity (CATS Consortium, 2010; Steinberg et al., 2004). The UCLA PTSD RI has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties (Steinberg et al., 2004). Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Plan of Analysis

We examined descriptive statistics for study variables including trauma exposure, internalizing/externalizing symptoms, and symptoms of PTSD. We conducted three multiple linear regression analyses to examine the relationship between the number of types of trauma and internalizing, externalizing, and PTSD symptoms, controlling for demographic and treatment setting covariates. We examined models using both continuous and categorical (0, 1–3, 4+) versions of the number of types of trauma, with no substantive difference; therefore, we present linear regression models using the continuous (0–8) version of the number of types of trauma. Four adolescents from the original study were excluded due to missing data on one or more of the study variables, resulting in a final sample of 94 for the Internalizing/Externalizing analyses. For the PTSD analysis, only adolescents reporting a history of trauma were included and two had missing data on PTSD symptoms (1 from outpatient psychiatry and 1 from the residential substance use disorder population), resulting in a sample 76. PTSD was a positively skewed variable. We examined a model using a log transformed variable which corrected for skewness. Findings were substantively the same, therefore findings are presented using the untransformed variable. Regression coefficients were evaluated for statistical significance at p < .05 using a two-tailed t-test. All analyses were completed using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Corp., 2010).

Results

The majority of adolescents reported experiencing at least one traumatic event (83%; M = 2.28, SD = 1.83; see Table 1). The most common events reported were experiencing or witnessing community violence, being beaten up/shot at/threatened in own town, and experiencing the death or serious injury of a loved one (see Figure 1). Average symptom scores overall and by clinical population are presented in Table 1. Average t-scores for internalizing and externalizing symptoms were below the threshold for clinical significance (M = 59.25, SD = 12.50 and M = 63.62, SD = 11.17, respectively). Sixteen (17.0%) and 27 (29.0%) of the adolescents reported clinically significant levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, respectively. Average PTSD severity scores for adolescents reporting a history of trauma were in the low range (M =13.81, SD = 11.68). Three (4.0%), 11 (14.5%), and 62 (81.6%) adolescents reported severe, moderate, and low PTSD symptoms, respectively. The inpatient population had the highest internalizing and PTSD symptoms, whereas, the highest externalizing symptoms were observed in the residential SA population.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables by Clinical Population

| Variable | Total (N = 94) | Inpatient Psychiatry (n = 24) | Medical (n = 10) | Outpatient Psychiatry (n = 30) | Residential SA (n = 30) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) / N (%) | ||||||||||

| Age (13–19) | 15.64 | (1.49) | 15.67 | (1.47) | 16.70 | (1.77) | 14.90 | (1.32) | 16.00 | (1.26) |

| Male | 34 | (36.2) | 4 | (16.7) | 1 | (10.0) | 13 | (43.3) | 16 | (53.3) |

| White | 69 | (73.4) | 18 | (75.0) | 2 | (20.0) | 26 | (86.7) | 23 | (76.7) |

| Internalizing Symptoms(t score) | 59.24 | (12.50) | 68.92 | (11.31) | 54.50 | (15.08) | 56.67 | (11.38) | 55.67 | (9.69) |

| Externalizing Symptoms (t score) | 63.62 | (11.17) | 64.25 | (8.60) | 52.80 | (9.05) | 58.20 | (9.37) | 72.13 | (9.05) |

| PTSD Symptom Severitya | 13.99 | (11.65) | 21.37 | (13.70) | 11.20 | (12.32) | 11.24 | (9.62) | 11.85 | (9.98) |

| Total Trauma Typesb | 2.28 | (1.83) | 2.96 | (2.33) | .90 | (1.29) | 1.60 | (1.19) | 2.87 | (1.63) |

Note: SA = Substance abuse. Chi-square and ANOVA used to assess differences across clinical populations. All variables were associated with clinical population at p < .05.

Scores range from 0–88; based on N = 76 (Inpatient psychiatric n = 20, Medical n = 5, Outpatient psychiatric n = 25, Residential SA n = 27)

Scores range from 0–8.

Our hypotheses related to internalizing and externalizing symptoms were partially supported. The multiple linear regression analyses indicated that youth self-report of total types of trauma was associated with externalizing symptoms (β = .31, p <.01), but not internalizing symptoms (β = .09, p = .39). Each additional type of trauma was associated with a 1.87 unit increase in externalizing symptoms. None of the demographic covariates were associated with internalizing or externalizing symptoms; however, treatment setting was significantly associated with both (see Tables 2 and 3). Specifically, inpatient adolescents reported higher internalizing symptoms than adolescents from any of the other settings. Inpatient adolescents reported higher externalizing symptoms than adolescents from the medical setting, but lower symptoms than those from the residential substance abuse setting.

Table 2.

Summary of Multiple Regression Analysis Examining the Association Between Prior Trauma and Internalizing Symptoms (N = 94)

| Variable | β | b | [95% CI for b] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Predicting Internalizing Symptoms | ||||

| Age | .16 | 1.36 | −.38 | 3.11 |

| Male | −.05 | −1.33 | −6.52 | 3.86 |

| White | .04 | 1.18 | −4.79 | 7.15 |

| Medical vs. Inpatient | −.35* | −14.01* | −23.80 | −4.22 |

| Outpatient vs. Inpatient | −.38* | −10.16* | −16.89 | −3.42 |

| Residential SA vs. Inpatient | −.49* | −13.18* | −19.64 | −6.72 |

| Total Types of Prior Trauma | .09 | .61 | −.80 | 2.02 |

Note: Adjusted R2 = .18, F(7, 86) = 3.99, p <.01. CI = confidence interval;

β = Standardized regression coefficients, b = unstandardized regression coefficients.

p < .05.

Table 3.

Summary of Multiple Regression Analysis Examining the Association Between Prior Trauma and Externalizing Symptoms (N = 94)

| Variable | β | b | [95% CI for b] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Predicting Externalizing Symptoms | ||||

| Age | .03 | .20 | −1.10 | 1.51 |

| Male | −.15 | −3.39 | −7.27 | .50 |

| White | .03 | .72 | −3.75 | 5.19 |

| Medical vs. Inpatient | −.21* | −7.64* | −14.97 | −.32 |

| Outpatient vs. Inpatient | −.11 | −2.54 | −7.58 | 2.49 |

| Residential SA vs. Inpatient | .39* | 9.22* | 4.39 | 14.05 |

| Total Types of Prior Trauma | .31* | 1.87* | .82 | 2.92 |

Note: Adjusted R2 = .43, F(7, 86) = 10.96, p <.01. CI = confidence interval;

β = Standardized regression coefficients, b = unstandardized regression coefficients.

p < .05.

Our hypothesis related to PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed adolescents was supported (β = .35, p <.01; see Table 4). Each additional type of trauma was associated with a 2.49 unit increase in PTSD symptom severity. No demographic variables were significantly related to PTSD symptom severity; however, treatment setting was related (highest among those seeking psychiatric inpatient services).

Table 4.

Summary of Multiple Regression Analysis Examining the Association Between Prior Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms (N = 76)

| Variable | β | b | [95% CI for b] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Predicting Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms | ||||

| Age | .04 | .35 | −1.65 | 2.36 |

| Male | −.07 | −1.55 | −7.10 | 4.01 |

| White | −.04 | −1.11 | −7.56 | 5.34 |

| Medical vs. Inpatient | −.15 | −6.87 | −19.34 | 5.59 |

| Outpatient vs. Inpatient | −.19 | −4.71 | −12.24 | 2.82 |

| Residential SA vs. Inpatient | −.32* | −7.68* | −14.44 | −.92 |

| Total Types of Prior Trauma | .35* | 2.49* | .77 | 4.20 |

Note: Adjusted R2 = .17, F(7, 68) = 3.14, p <.01. CI = confidence interval;

β = Standardized regression coefficients, b = unstandardized regression coefficients.

p < .05.

Discussion

The rate of trauma exposure (83%) was high among this sample of adolescents ages 13–19 drawn from four treatment settings. This rate is similar to those observed in NCTSN studies and consistent with behavioral health service-seeking adolescent populations. As hypothesized, a greater number of types of prior trauma was related to self-reported externalizing symptoms (e.g., aggressive behavior, rule-breaking), which is consistent with prior research using primarily parent/caregiver or clinician report of symptoms (Greeson et al., 2013; Layne et al., 2014; Wamser-Nanney et al., 2013). Externalizing symptoms are of particular concern, given that risk behaviors such as substance use put adolescents at risk for recurrent trauma (Begle et al., 2011; Kim, Conger, Elder, & Lorenz, 2003; Kingston & Raghavan, 2009), potentially further compounding posttraumatic sequelae.

We did not find support for our hypothesis that internalizing symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, somatic complaints) would be related to exposure to more types of trauma. Such a relationship was observed among adolescents in the NCTSN using parent/caregiver or clinician report of youth internalizing symptoms (Greeson et al., 2014). This discrepancy may be accounted for by the fact that adolescent report on the YSR and parent-equivalent, the Child Behavior Checklist, are known to be only modestly correlated, and particularly so for internalizing symptoms (Gearing, Schwalbe, MacKenzie, Brewer, & Ibrahim, 2015; Salbach-Andrae, Lenz, & Lehmkuhl, 2009). Using both parent and adolescent report may give the most complete picture of trauma-related symptomatology; unfortunately, parent report was not available for this study.

With regards to PTSD symptoms, consistent with existing research, multiple types of prior trauma exposure was related to greater PTSD symptom severity. We observed a low rate of severe PTSD symptoms (≥ 38; 3 out of 76 adolescents), which is consistent with studies showing that PTSD appears to be a relatively rare outcome of trauma, despite the high rates of trauma among youth (Copeland et al., 2007) and underscores that PTSD is only one of the possible behavioral health outcomes to consider among adolescent trauma populations. Due to sample size limitations, we were unable to examine the relation between internalizing, externalizing, and PTSD symptoms and which symptoms are best accounted for by the number of types of trauma experienced by adolescents; however, future research in this area would help elucidate the nature of trauma exposure on adolescent behavioral health and well-being and primary treatment targets.

Additionally, to shed light on how specific types of trauma might interact with adolescent risk and resilience factors, future research with large, diverse samples of youth and comprehensive assessments of trauma exposure history, internalizing, externalizing, and posttraumatic symptomatology is warranted. For instance a study of adverse life events among urban African American youth suggests traumatic and stressful events lead to specific symptoms of internalizing and externalizing among these youth depending on gender and the nature of coping mechanisms used (e.g., avoidance is protective for women but not men; Sanchez Lambert, & Cooley-Strickland, 2013).

Our findings corroborate research showing that multiple trauma exposure, regardless of the type of trauma, is related to a breadth of posttraumatic symptomatology (Cloitre et al., 2009; Finkelhor et al., 2007; Green et al., 2010; McMahon, Grant, Compas, Thurm, & Ey, 2003), which has implications for treatment. Psychological interventions for trauma-exposed adolescents that address externalizing symptoms in addition to trauma-specific symptoms (e.g., nightmares; avoidance) may be particularly important, and will perhaps become more the norm of evidence-based practice for youth given the addition of externalizing symptoms to the most recent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) PTSD diagnosis (Miller, Wolf, & Keane, 2014). For example, a modular transdiagnostic treatment that addresses multiple comorbid conditions common among youth both with and without posttraumatic stress symptoms is available and has demonstrated effectiveness (Chorpita et al., 2017; Weisz et al., 2012). Another benefit to modular transdiagnostic treatment is that such an approach can support the treatment needs of adolescents presenting with internalizing and externalizing symptoms, regardless of whether the symptoms are trauma-related. However, it remains an empirical question whether externalizing or internalizing symptoms consequent to traumatic stress reactions require trauma-focused treatment or if they may be responsive to a generic transdiagnostic approach designed to target these symptoms more broadly.

Study findings also corroborate the value of determining whether the clinical presentation of adolescents presenting for behavioral health treatment may better reflect Complex PTSD (Sar, 2011) or Developmental Trauma Disorder (van der Kolk, 2005), than PTSD. Traumatic experiences among youth occur during developmentally rich periods of time and are known to disrupt biological and psychosocial development, particularly when chronic and of an interpersonal nature (D’Andrea, Ford, Stolbach, Spinazzola, & van der Kolk, 2012). In fact, interpersonal trauma was the most frequently endorsed type of trauma in our sample. In recognition of the unique constellation of psychopathology associated with chronic, developmentally salient, interpersonal trauma, the World Health Organization will be releasing the International Classification of Disorders-11 in 2018 that includes a diagnosis of Complex PTSD. The diagnosis consists of PTSD symptoms in addition to affect dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbed relationships (Hyland et al., 2017). The DSM has yet to incorporate such a diagnosis but expanded the diagnosis of PTSD in DSM-5 to include the related symptoms of risk taking behavior and negative self-perception (e.g., guilt and self-blame; American Psychiatry Association, 2013). Developmental Trauma Disorder shares similarities with Complex PTSD, but recognizes the pervasive effects of a wider variety of traumatic experiences on child development (e.g., neglect), even if criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD is not met. A diagnosis of Complex PTSD or Developmental Trauma Disorder would have implications for treatment. For instance, treatment may emphasize the primacy of building trust and therapeutic alliance and improving adolescents’ affect regulation before moving into focused work on traumatic memories (Briere & Lanktree, 2013).

Although we did not hypothesize about the relationships between treatment setting and total trauma types, an interesting relationship emerged. Adolescents presenting for inpatient psychiatric and residential SA treatment reported the greatest number of types of trauma (an average of nearly 3), which may suggest that severity of behavioral health problems (i.e., those requiring inpatient treatment) is associated with a greater exposure to trauma. In addition to high levels of prior trauma, the residential SA adolescents also reported an average level of externalizing symptoms above the clinical cut-off, and youth with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders are known to have particularly complex psychosocial needs (Suarez, Belcher, Briggs, & Titus, 2012). It may be that adolescents seeking inpatient or residential care are subject to familial and social environmental contexts hallmarked by what Layne and colleagues (2009) refer to as “risk factor caravans,” or constellations of personal, social, group membership or condition, and material resources, that co-occur and co-develop over time. In addition to symptom severity, seeking inpatient and residential care may be a reflection of complex psychosocial contexts in which youth and their families lack other resources to address these adolescents’ behavioral health symptoms. System-level interventions (e.g., integrated and coordinated care) may be required above and beyond targeted psychotherapeutic approaches to support these adolescents in their recovery.

Limitations

In addition to those previously mentioned, study findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, findings based on this secondary data analysis are most directly applicable to adolescents presenting for behavioral health services. Relatively few adolescents were recruited from the general medical setting. Additionally, findings are limited to ages studied (13–19) and are largely applicable to adolescents identified as White (73% of the sample). In regard to gender, there were relatively few male youth in the inpatient and medical populations, limiting what can be said in this study with regards to the experiences of male adolescents from these populations.

Measurement considerations include that trauma exposure was measured using self-report, which is subject to bias in reporting and errors in memory recall, and may therefore not accurately reflect all of the adolescents’ experiences. Studies using adolescent self-report in addition to caregiver report may provide a more complete picture. Additionally, trauma history was assessed with a relatively brief measure used to screen for PTSD and only included 12 original (and ultimately 8 collapsed) categories of trauma. A more exhaustive measure, such as the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 (Pynoos & Steinberg, 2013), may provide more accurate estimates of the impact of trauma types on symptoms and symptom severity. Due to the cross-sectional study design, we were not able to determine whether a greater number of types of trauma actually causes greater symptom severity among adolescents. It may be that a third variable not observed (e.g., socioeconomic conditions) actually accounts for the observed association.

Conclusion

Trauma is a common experience among adolescents, particularly those presenting for behavioral health services, making trauma-informed care (Hodas, 2006) essential in these service delivery settings. Additionally, given that avoidance is a core PTSD symptom and could lead clinicians to miss observation of trauma and trauma-related symptoms among adolescents with externalizing difficulties, trauma screening and assessment is critical in these settings. Experiencing multiple traumatic events is associated with a broad spectrum of psychological and behavioral sequelae, indicating the need for psychotherapeutic interventions that address comorbidity and complex clinical presentations. In particular, treatments to reduce risk behaviors and prevent recurrent trauma may be particularly important given the negative impact of multiple traumatic events on children and adolescents. Public health and community-based approaches that aim to reduce trauma exposure and promote youth, family, and community resilience are also needed (Layne et al., 2009).

Clinical Impact Statement.

The rate of trauma exposure was high (83%) among this sample of adolescents ages 13–19 drawn from four treatment settings. A greater number of types of prior trauma was related to higher self-reported externalizing symptoms and PTSD symptom severity. Psychological interventions for trauma-exposed adolescents that address externalizing symptoms in addition to trauma-specific symptoms (e.g., nightmares; avoidance) may be particularly important. This includes interventions to reduce risk behaviors and prevent recurrent trauma, given the negative impact of multiple traumatic events on children and adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services and a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health T32MH082709.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition, Text Revision) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Begle AM, Hanson RF, Danielson CK, McCart MR, Ruggiero KJ, Amstadter AB, … Kilpatrick DG. Longitudinal pathways of victimization, substance use, and delinquency: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(7):682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Lanktree CB. Integrative treatment of complex trauma for adolescents (ITCT-A): A guide for the treatment of multiply-traumatized youth, 2nd edition. Los Angeles, CA: USC Adolescent Trauma Training Center, National Child Traumatic Stress Network, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, McNiff J. Specificity of autonomic arousal to DSM-IV Panic Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(6):487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CATS Consortium. Implementation of CBT for youth affected by the World Trade Center disaster: Matching need to treatment intensity and reducing trauma symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(6):699–707. doi: 10.1002/jts.20594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Park AL, Ward AM, Levy MC, Cromley T, … Krull JL. Child STEPs in California: A cluster randomized effectiveness trial comparing modular treatment with community implemented treatment for youth with anxiety, depression, conduct problems, or traumatic stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2017;85(1):13. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Begle AM, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Danielson CK, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Exposure to interpersonal violence and risk for PTSD, depression, delinquency, and binge drinking among adolescents: Data from the NSA-R. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25(1):33–40. doi: 10.1002/jts.21672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, Petkova E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(5):399–408. doi: 10.1002/jts.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois K, Voss B, Morgan AF. Screening for mental, chemical dependency, and co-occurring disorders among adolescents: The Global Appraisal of Individual Needs – Short Screener (GAIN-SS) Washington Institute for Mental Illness Research and Training (WIMIRT), Harborview Medical Center and Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center; 2007. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland W, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea W, Ford J, Stolbach B, Spinazzola J, van der Kolk BA. Understanding interpersonal trauma in children: Why we need a developmentally appropriate trauma diagnosis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(2):187–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect: The International Journal. 2007;31(1):7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. The developmental epidemiology of childhood victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(5):711–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing RE, Schwalbe CS, MacKenzie MJ, Brewer KB, Ibrahim RW. Assessment of adolescent mental health and behavioral problems in institutional care: Discrepancies between staff-reported CBCL Scores and Adolescent-Reported YSR scores. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2015;42(3):279–287. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0568-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Goodman LA, Krupnick JL, Corcoran CB, Petty RM, Stockton P, Stern NM. Outcomes of single versus multiple trauma exposure in a screening sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;13(2):271–286. doi: 10.1023/A:1007758711939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JK, Briggs EC, Layne CM, Belcher HM, Ostrowski SA, Kim S, … Fairbank JA. Traumatic childhood experiences in the 21st century: Broadening and building on the ACE studies with data from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29(3):536–556. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodas GR. Responding to childhood trauma: The promise and practice of trauma informed care. Pennsylvania Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services; 2006. pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges M, Godbout N, Briere J, Lanktree C, Gilbert A, Kletzka NT. Cumulative trauma and symptom complexity in children: A path analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(11):891–898. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland P, Shevlin M, Elklit A, Murphy J, Vallières F, Garvert DW, Cloitre M. An assessment of the construct validity of the ICD-11 proposal for complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2017;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1037/tra0000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2010. Released. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett K, Williams L, Finkelhor D, Steinberg RJ. Impact of sexual abuse on children: A review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(1):164–180. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61(5):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D, Ruggiero K, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick H, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Conger RD, Elder GH, Jr, Lorenz FO. Reciprocal influences between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2003;74(1):127–143. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston S, Raghavan C. The relationship of sexual abuse, early initiation of substance use, and adolescent trauma to PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(1):65–68. doi: 10.1002/jts.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Devlin B. Internalizing disorders in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39(1):47–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Beck CJ, Rimmasch H, Southwick JS, Moreno MA, Hobfoll SE. Promoting “resilient” posttraumatic adjustment in childhood and beyond: “Unpacking” life events, adjustment trajectories, resources, and interventions. In: Brom D, Pat-Horenczyk R, Ford J, editors. Treating traumatized children: Risk, resilience, and recovery. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Greeson JKP, Ostrowski SA, Kim S, Reading S, Vivrette RL, Briggs EC, … Pynoos RS. Cumulative trauma exposure and high risk behavior in adolescence: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Data Set. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6(1):S40–S49. doi: 10.1037/a0037799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Trauma exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):815–830. e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon SD, Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, Ey S. Stress and psychopathology in children and adolescents: Is there evidence of specificity? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(1):107–133. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Keane TM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in DSM-5: New criteria and controversies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2014;21(3):208–220. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM. UCLA PTSD reaction index for children/adolescents–DSM-5. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos R, Rodriguez N, Steinberg A, Stuber M, Frederick C. The University of California at Los Angeles Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (UCLA-PTSD RI) for DSM-IV. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Layne CM, Liang LJ, Vivrette RL, Briggs EC, … Fairbanks JA. Modeling constellations of trauma exposure in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Data Set. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6(1):S9–S17. doi: 10.1037/a0037767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salbach-Andrae H, Lenz K, Lehmkuhl U. Patterns of agreement among parent, teacher and youth ratings in a referred sample. European Psychiatry. 2009;24(5):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez YM, Lambert SF, Cooley-Strickland M. Adverse life events, coping and internalizing and externalizing behaviors in urban African American youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22(1):38–47. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9590-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sar V. Developmental trauma, complex PTSD, and the current proposal of DSM-5. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2011;2(1):5622. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.5622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2004;6(2):96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez LM, Belcher HME, Briggs EC, Titus JC. Supporting the need for an integrated system of care for youth with co-occurring traumatic stress and substance abuse problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;49(3):430–440. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA. Developmental trauma disorder. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35(5):401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wamser-Nanney R, Vandenberg BR. Empirical support for the definition of a complex trauma event in children and adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(6):671–678. doi: 10.1002/jts.21857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK, … Gray J. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):274–282. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]