Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has poor prognosis due to various mutations, e.g., in the FLT3 gene. Therefore, it is important to identify pathways regulated by the activated Flt3 receptor for the discovery of new therapeutic targets. The Myc network of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes is involved in mechanisms regulating proliferation and survival of cells, including that of the hematopoietic system. In this study, we evaluated the expression of the Myc oncogenes and Mxd antagonists in hematopoietic stem cell and myeloid progenitor populations in the Flt3-ITD-knockin myeloproliferative mouse model. Our data shows that the expression of Myc network genes is changed in Flt3-ITD mice compared with the wild type. Mycn is increased in multipotent progenitors and in the pre-GM compartment of myeloid progenitors in the ITD mice while the expression of several genes in the tumor suppressor Mxd family, including Mxd1, Mxd2, and Mxd4, is concomitantly downregulated, as well as the expression of the Mxd-related gene Mnt and the transcriptional activator Miz-1. LSKCD150+CD48− hematopoietic long-term stem cells are decreased in the Flt3-ITD cells while multipotent progenitors are increased. Of note, PKC412-mediated inhibition of Flt3-ITD signaling results in downregulation of cMyc and upregulation of the Myc antagonists Mxd1, Mxd2, and Mxd4. Our data provides new mechanistic insights into downstream alterations upon aberrant Flt3 signaling and rationale for combination therapies for tyrosine kinase inhibitors with Myc antagonists in treating AML.

1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), despite aggressive treatment regimes, has a poor prognosis, and cure is difficult to attain. Mutations in the tyrosine kinase receptor Flt3, including internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations and tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) mutations, are the most common changes in AML, which constitutively activate the Flt3 receptor [1]. Flt3 regulates growth and survival of myeloid progenitor cells; therefore, mutations in FLT3 effectively abrogate growth-regulating controls [2]. Interestingly, mutations in FLT3 are correlated with shorter progression-free survival and overall survival [3, 4].

Treatment strategies aimed at inhibiting the activated Flt3-ITD receptor have been evaluated in clinical trials; however, the use of Flt3-ITD inhibitors as single agents resulted in poor clinical outcome due to emergence of drug-resistant cells [5]. This underscores the need to develop combination treatment strategies [6]. Therefore, it is important to identify pathways regulated by the activated Flt3 receptor for the development of new treatment targets. Several pathways have been implicated downstream of the mutated Flt3 receptor in leukemias, including the Wnt pathway and the JAK/STAT pathway [7, 8].

Interestingly, the MYC oncogenes have been implicated downstream of Flt3-ITD signaling [9]. The MYC family genes, including MYC, MYCN, and MYCL1, are proto-oncogenes and known to be overexpressed or mutated in a plethora of different tumors, including that of the hematopoietic system [10, 11]. The MYC proteins function as transcription factors and bind to specific E-box DNA sequences, in promoters of target genes by heterodimerizing with their partner MAX [12]. However, Myc also regulates genes independent of DNA binding via Miz-1 protein [13]. Intriguingly, bone marrow-specific overexpression of Mycn results in rapid development of acute myeloid leukemia [14]. Furthermore, Myc has also been shown to induce myeloid myeloproliferative disease, even though mutations in myeloid neoplasias are not common [15]. The Mxd family of proteins also heterodimerizes with Max and binds to the common E-box sequences and generally works in an antagonistic way towards Myc [12].

Importantly, several reports have implicated Myc as a downstream target of Flt3-ITD signaling. To this end, it was shown that Flt3-ITD regulates cMyc via Wnt signaling [8]. Additionally, Flt3-ITD inhibits Foxo3a [16], which in turn suppresses the Myc antagonist Mxi-1 (Mxd2) to increase Myc activity [17]. Interestingly, studies of Myc function in hematopoietic stem cells have implicated Myc in pushing the HSCs out of the niche and into a proliferative progenitor state [18]. Given that both Flt3 and Myc regulate HSCs' self-renewal and differentiation, evaluating the interplay between Flt3-ITD signaling and Myc molecules may represent therapeutic targets for AML therapy.

In this study, we investigated the Myc network genes in different subpopulations in the bone marrow, including myeloid progenitors and stem cell populations, in the Flt3-ITD myeloproliferative mouse model [19]. Here, we report that the expression of the Myc network genes is changed in the Flt3-ITD mouse model, mainly with upregulation of the Myc genes and concomitant downregulation of the Myc antagonists, the Mxd genes, in different hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell subpopulations, as well as downregulation of the Mxd-related gene Mnt and the transcriptional activator Miz-1. Moreover, PKC412-mediated inhibition of Flt3-ITD signaling results in downregulation of c-Myc and upregulation of the Myc antagonists Mxd1, Mxd2/Mxi1, and Mxd4.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and PKC412 Inhibitor

MV4-11 cells were cultured in IMDM medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 20% FCS, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were constantly maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. The Flt3-ITD phosphokinase inhibitor was added to cell cultures of MV4-11 cells in 2 different concentrations for 15 minutes before the cells were harvested for mRNA extraction (0.1 mM and 1 mM) (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA).

2.2. Mice

Flt3-ITD-knockin mice on C57BL/6 background were previously described [19]. WT (Flt3+/+) C57BL/6 littermate mice were used as WT controls. All experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee at Lund University.

2.3. Fluorescent Antibodies and Immunomagnetic Beads Used for FACS Analysis and Sorting

Antibodies used for cell surface staining were as follows: CD11b/Mac1 (M1/70), CD4 (H129.19), CD8a (53–6.7), B220/CD45 (RA3–6B2), CD5 (Ly1), Ter119 (Ter-1119), Gr1/Ly6G and Ly6C (RB6–8C5), CD19 (ID3), CD41/Itga2b (MWReg30), and CD135/Flt3 (A2F10.1) (104) (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) and NK1.1 (PK136), Sca1 (D7), CD117/c-Kit (2B8), CD16/32 (93), and CD105/Eng (MJ7/18) (eBioscience). Biotinylated antibodies were visualized with streptavidin-QD655 (Invitrogen) or streptavidin-tricolor (Invitrogen), and purified lineage antibodies were visualized with polyclonal goat anti-rat tricolor (Invitrogen) or polyclonal goat anti-rat-QD605 (Invitrogen). MACS column enrichment of c-Kit+ cells was done using anti-CD117 immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) as previously described [20].

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis

Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells were analyzed as previously described. [21–23]. Briefly, bone marrow (BM) cells were stained with a cocktail of purified rat antibodies against lineage markers B220, CD4, CD5, CD8α, CD11b, Gr1, and Ter119. Lineage+ cells were visualized with a goat anti-rat-QD605 staining, followed by c-Kit enrichment for sorting analyses. Thereafter, hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells were defined as Lin−Sca1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells, pre-granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (pre-GMPs: Lin−c−Kit+Sca1− [LSK−] CD41−CD16/32low/−CD150−CD105low/−), granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs: LKS−CD16/32hiCD150−), and multipotent progenitors (MPPs: Lin−Sca1+ c-Kit+CD150−CD105low/−). Propidium iodide (Invitrogen) was used to exclude dead cells. Cell acquisition and analysis were performed on a 4-laser LSRII (BD Biosciences) using FlowJo version 8.8 software (TreeStar). Cell sorting was done on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences).

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

For analyzing gene expression in myeloid progenitors (pre-GM, GMPs) as well as in hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors (MPPs), cells from these populations were FACSAria-sorted directly into 75 μl of buffer RLT and frozen at −80°C. Total RNA extraction and DNase treatment were performed with the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen Inc., California) according to the manufacturer's instructions for samples containing ≤105 cells. Eluted RNA samples were reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase Kit including random hexamers (Invitrogen) according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. For gene expression in LT-HSCs as well as in MPPs using the Slam marker staining (including CD150 and CD48), the CelluLyser™ protocol (TaTaa, Gothenburg, Sweden) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Shortly, cells were FACSAria-sorted into 5.5 ∝ l lysis buffer where RNA was directly reverse-transcribed using the Transcriptor First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche). Q-PCR reactions with the diluted cDNA samples were analyzed with TaqMan gene expression assays (ABI, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. TaqMan Assays-on-Demand probes used are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. All experiments were performed in triplicate and from at least two different sorts, and differences in cDNA input were compensated by normalizing against β-actin or HPRT expression levels. The fold induction ratio was calculated by the Pfaffl equation:

| (1) |

Statistical analysis was performed with two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test on log-converted values (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

3. Results

3.1. Myeloid Progenitor and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Populations Are Changed in Flt3-ITD Mice

To evaluate the gene expression of the MYC network genes in the bone marrow of Flt3-ITD mice compared with wild-type (WT) mice, hematopoietic stem cell and myeloid progenitor (MPP) subpopulations were identified by staining for surface markers, analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and subsequently sorted. Initially, myeloid progenitors including pre-GM and granulocytic myeloid progenitors (GMPs), as well as Lin−Sca-1+Kit+ (LSK) cells, within which hematopoietic stem cells reside, were sorted using a staining procedure including endoglin and the SLAM receptor CD150, as described previously [23].

The Flt3-ITD mouse has a myeloproliferative disease with expanded myeloid populations [19]. Consistently, we observed that myeloid progenitors (MPs/LK; Lin−Sca-1−Kit+ cells) in Flt3-ITD mice are increased to 69.5% in comparison with 54.9% MPs in WT mice (Figure 1(a)). Moreover, we observed that the relative distribution of subpopulations within the MP compartment was altered as well. Importantly, progenitors of the granulocytic/monocytic pathway (pre-GM and GMPs) were increased in Flt3-ITD mice in comparison to WT mice, as we observed that pre-GMs were increased from 39% in WT to 65% in Flt3-ITD mice and GMPs were increased from 41% in WT to 86% in ITD mice (Figure 1(a)). Consistent with our previous data [24], the progenitors of the megakaryocytic and erythroid pathway were diminished (Figure 1(a)). The expression of Flt3 is altered or diminished due to the ITD mutation; therefore, staining to identify HSC subpopulations by utilizing the expression of the Flt3 receptor is not feasible. Here, we identified long-term (LT-) HSCs as CD150+CD105+ utilizing CD150 and endoglin (CD105), while MPPs were identified as CD150−/CD105+. Intriguingly, we observed a decrease in LT-HSCs in favor of MPPs in the ITD mice (Figure 1(b)). Collectively, the above data set indicates that ITD mutation in Flt3 results in the expansion of the pre-GM, GMP, and MPP compartments.

Figure 1.

Myeloid progenitor and hematopoietic stem cell populations are changed in Flt3-ITD mice. Analysis of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) and multipotent progenitor (MPP) subpopulations within the Lin−Sca-1+Kit+ (LSK) population, as well as myeloid progenitors including pre-GM and granulocytic myeloid progenitors (GMPs), in the bone marrow of Flt3-ITD and wild-type (WT) mice, was performed using a staining procedure including endoglin and the SLAM receptor CD150.

3.2. Myeloid and Multipotent Progenitors Have Altered Myc Network Genes in Flt3-ITD Mice

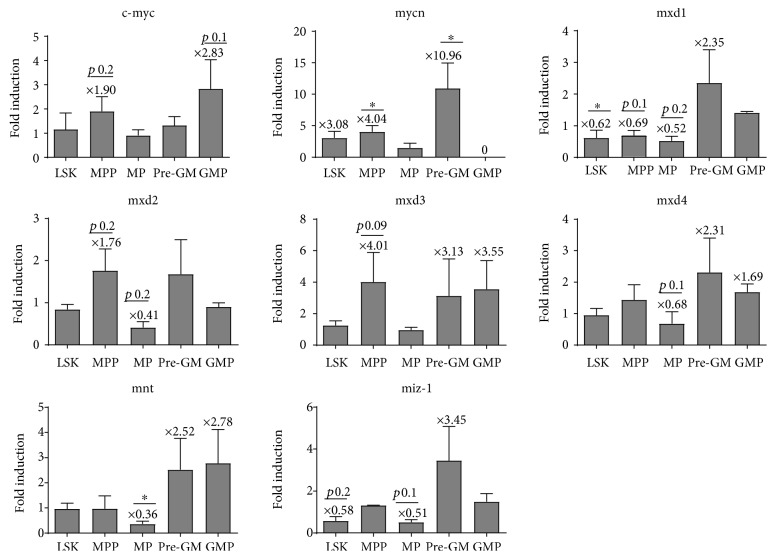

Next, we evaluated the expression of the Myc network genes including cMyc and Mycn, as well as the Mxd family of Myc antagonists (Mxd1, Mxd2/Mxi1, Mxd3, and Mxd4), in stem and progenitor subpopulations in mice with the Flt3-ITD mutation and littermate WT controls by quantitative real-time PCR (Q-RT-PCR) (Figure 2). The mRNA of the cMyc gene was increased in Flt3-ITD MPPs (1.9-fold induction), as well as in Flt3-ITD GMPs (2.83-fold induction). Of note, the Mycn expression was increased in all the populations investigated in Flt3-ITD mice, except for GMPs where the expression of Mycn was turned off. Mycn was most prominently upregulated in MPPs and pre-GM cells (4.04- and 10.96-fold induction, respectively). Furthermore, analysis of the expression of the Myc antagonists, the Mad family genes, showed downregulation of Mxd1 in LSK cells (0.62-fold reduction), MPPs (0.69-fold reduction), and MPs (0.52-fold reduction). Mxd2/Mxi1 was downregulated in LSK (0.77-fold reduction) and MP (0.41-fold reduction) cells and Mxd4 in MPs (0.68-fold reduction). Additionally, Mxd2/Mxi1 and Mxd3 were upregulated in MPPs. The MNT gene, an MXD family-related gene, which is coexpressed with Myc in proliferating cells and functions as a repressor of Myc target genes [25] was downregulated (0.36-fold reduction) in myeloid progenitors (MPs) in Flt3-ITD mice. Similarly, the MIZ-1 gene, a transcriptional activator which is involved in upregulating growth-repressing genes such as p21, was downregulated in LSK cells (0.58-fold reduction) and MPs (0.51-fold reduction). Max, the Myc- and Mxd-interacting partner, was significantly increased in MPPs (1.75-fold induction) and significantly decreased in MPs (0.48-fold reduction) (data not shown). Collectively, these data indicate that the ITD mutation in Flt3 results in the alteration of Myc network genes.

Figure 2.

Myeloid and multipotent progenitors have altered Myc network genes in Flt3-ITD mice. The expression of Myc network genes was carried out with reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-Q-PCR) in sorted subpopulations of murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Fold induction was calculated as a ratio of Flt3-ITD : WT samples. Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t-test on log-converted values (∗p < 0.05). Significance was shown in many of the described altered expression levels; however, some changes showed low p values but did not quite reach statistically significance due to variances in the expression levels.

3.3. Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Flt3-ITD Mice Have Altered Myc Network Expression

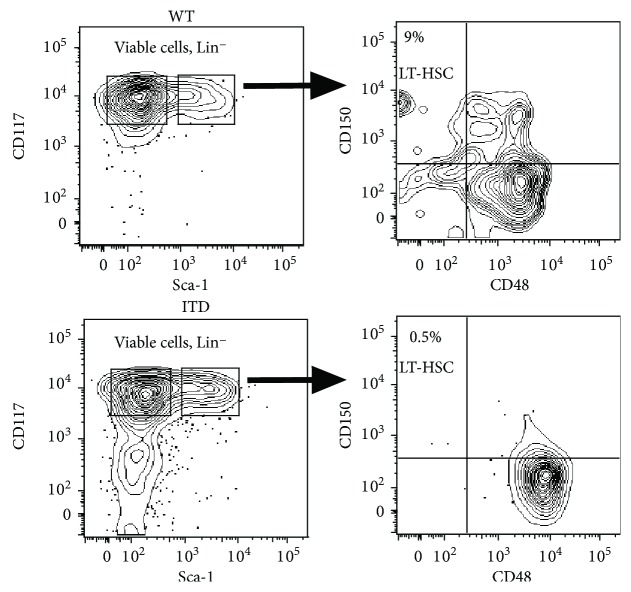

Next, we subdivided the hematopoietic stem cell compartment into long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) and MPPs, utilizing the SLAM receptor staining with CD150 and CD48 [22], and cells were sorted by flow cytometry for subsequent gene expression analysis. Of note, the LT-HSCs (LSKCD150+CD48−) were decreased in the Flt3-ITD cells, as described previously [26], and the MPPs were increased. Intriguingly, MPPs expressed higher levels of CD48 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Flt3-ITD mice have altered frequencies of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Next, we subdivided the hematopoietic stem cell compartment into long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) and MPPs, utilizing the SLAM receptor staining with CD150 and CD48, and cells were sorted by flow cytometry for subsequent gene expression analysis.

Expression of the Myc network genes was evaluated in LSK, LT-HSC (CD150+CD48−), MPP (CD150−CD48+), and MP cells. Intriguingly, the expression of the cMyc gene did not change in LSK, LT-HSC, MPP, and MP cells as identified in the SLAM receptor-based staining in contrast to the staining including the endoglin marker (Figures 4 and 1). Conversely, the Mycn mRNA was increased in MPP cells (2.98-fold induction) (Figure 4), comparative with the results from the analysis in the endoglin/CD150 staining protocol (Figure 2). However, the results in this staining did not quite reach significant values due to variations. Importantly, Mxd1 showed a significant decrease in expression in LT-HSCs (0.63-fold reduction), as well as in MPPs (0.62-fold reduction) and the LSK compartment (0.64-fold reduction), which, however, did not reach significant levels (Figure 4). Of note, Mxd2/Mxi1 and Mxd4 were significantly decreased in the LSK compartment; however, their expression did not change in LT-HSCs, MPPs, and MPs. Conversely, Mxd3 did not change significantly in any of the subpopulations (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hematopoietic stem cells in Flt3-ITD mice have altered Myc network expression. The expression of Myc network genes was carried out with reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-Q-PCR) in hematopoietic stem cells. Fold induction was calculated as a ratio of Flt3-ITD : WT samples. Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t-test on log-converted values (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

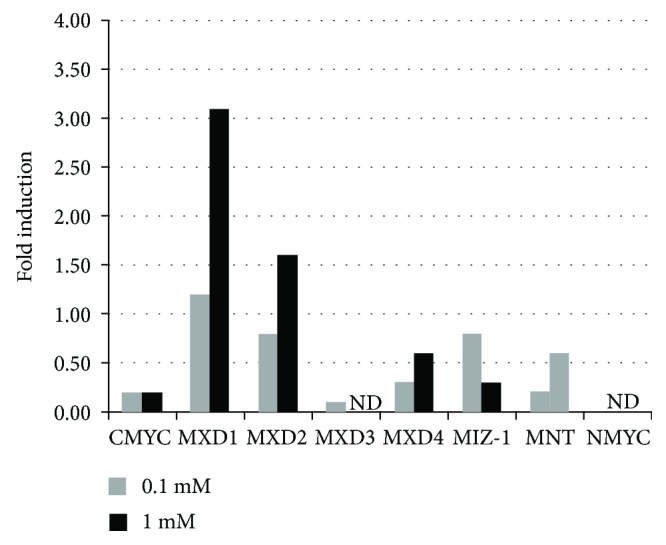

3.4. Small Molecule Inhibitor, PKC412, Modulates the Expression of Myc Network Genes in Human MV4-11 Cells

PKC412 is an inhibitor of FLT3 autophosphorylation, thereby inhibiting downstream signaling [27]. It has shown to inhibit growth of primary Flt3-ITD mutant blasts [28]. To investigate whether Flt3-ITD inhibition exerts antileukemic activity via modulation of the Myc network, we treated the human Flt3-ITD mutated leukemia cell line, MV4-11, with PKC412 at two different concentrations (0.1 mM and 1 mM) and analyzed the expression of Myc network genes. Of note, PKC412 reduced cMyc expression to the same extent at both concentrations. Conversely, the expression of the Myc antagonists Mxd1 and Mxd2 was increased in a dose-dependent manner in MV4-11 cells treated with PKC412 (Figure 5), as well as the expression of Mxd4, but to a lesser extent. Intriguingly, MV4-11 cells do not express Mycn (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Small molecule inhibitor, PKC412, modulates the expression of Myc network genes in human MV4-11 cells. The human Flt3-ITD mutated leukemia cell line, MV4-11, was treated with the Flt3-inhibitor PKC412 at two different concentrations (0.1 mM and 1 mM) for 15 minutes. Expression analysis of the Myc network genes was carried out with RT-Q-PCR. ND: not detected.

4. Discussion

Currently, a rapid development of targeted therapies against specifically overexpressed or mutated molecules in AML is ongoing. Clinical trials against mutated molecules found in AML, e.g., IDH1 and IDH2, have recently been initiated [29]. Considering the risk of relapse with the current treatment, it is important to identify pathways regulated by the activated Flt3 receptor for the identification of new treatment targets. The Myc network of oncogenes and tumor suppressors is often changed in a plethora of tumors. The overexpression of the MYC and MYCN oncogenes is mostly not due to actual mutations in the genes, but their expression is deregulated due to upstream activated pathways and molecules [30]. However, there are exceptions to the rule, as MYCN is amplified in neuroblastomas [31]. Myc and Mycn overexpression has been shown to initiate myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms and could therefore be possible targets for inhibiting leukemic cell proliferation and viability. The Mxd network of tumor suppressors has been shown to be downregulated or deleted in different tumor types including prostate adenocarcinoma [32]. In this study, we have analyzed the possible role of the Myc network in Flt3-ITD-induced myeloproliferative disease. Flt3-ITD is one of the most common mutations in AML and is correlated with poor prognosis. Strategies of inhibiting the overactivated Flt3-ITD tyrosine kinase or pathways downstream of this receptor would therefore be of interest in treating AML patients with this mutation. Efforts with Flt3-ITD inhibitors to treat AML are ongoing. However, results have shown that the Flt3-ITD inhibitor should be used in combination with other treatments to avoid the development of drug resistance.

Herein, we report that myeloid progenitors (MPs) are increased in adult Flt-3ITD mice, which is consistent with other reports. Intriguingly, fetal Flt3-ITD mice have a normal MP compartment and are protected from leukemic transformation [33]. Similarly, LT-HSCs (LSKCD150+48−) were reported to be present in normal numbers in Flt3-ITD fetal livers before the onset of myeloproliferative disease. However, we here show that LT-HSCs decrease in favor of MPPs in Flt3-ITD mice which has developed a myeloproliferative disease, which has also been shown in other reports ([34, 35, 26]). Evidence has shown that the effect of Flt3-ITD on LT-HSC homeostasis is cell autonomous [26]. Changes in the expression of the Myc network genes downstream of Flt3-ITD could therefore be responsible for an expansion of leukemic multipotent progenitors. Of note, STAT3 is upregulated in Flt3-ITD MPPs [34]. Moreover, in adult progenitors, Flt3-ITD induces self-renewal in a STAT5-dependent manner [36]. Interestingly, lineage-specific STAT5 activation in hematopoietic progenitor cells predicts the FLT3+-mediated leukemic phenotype in mice [37], and the STAT signaling pathway has been reported to increase Myc activity. These data highlight the involvement of STAT signaling in connection with the Myc network in aberrant hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations in Flt3-ITD, which is thus also a potential therapeutic target in Flt3-ITD leukemia.

We found that the Myc network of oncogenes and tumor suppressors is changed in Flt3-ITD myeloproliferative mice compared with wild-type mice. Generally, the Myc gene expression was increased, and the expression of the Myc antagonists, mainly Mxd1, Mxd2/Mxi1, Mxd4, Mnt, and Miz-1, was decreased. Myc has been shown to be involved in displacing quiescent hematopoietic stem cells from their niche to more proliferative progenitor cells [38]. This can be correlated with our results showing the change in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell subpopulation distribution, where the long-term hematopoietic stem cells are decreased in Flt3-ITD mice and the multipotent progenitors increased. Our data shows that cMyc was increased in Flt3-ITD multipotent progenitors (MPPs) as was Mycn in LSK, MPP, and pre-GM cells. Importantly, c-MYC has been reported to induce the expression of the deubiquitinase USP22, which in turn reduced ubiquitination and enhanced the stability of SIRT1 in CD34+ Flt3-ITD cells. Of note, inhibition of SIRT1 expression or activity reduced the growth of Flt3-ITD AML [39]. Additionally, c-MYC generates repair errors by regulating transcriptional activation and expression of the alternative nonhomologous end-joining pathway resulting in aberrant DNA repair in Flt3-ITD leukemia [40]. Further, N-Myc overexpression mechanistically results in the hyperproliferation of myeloid cells by decreasing transforming growth factor β signaling and increasing c-Jun-NH2-kinase signaling to cause AML [14]. Collectively, these data underscore the importance of inhibition of the Myc molecules in treating Flt3-ITD mutated AML. Furthermore, we observed the downregulation of Mxd family genes, i.e., Mxd1, Mxd2/Mxi1, and Mxd4. Interestingly, Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) has been identified as an upstream transcriptional regulator of Mxd1 and Myc in myeloid leukemias [41]. Intriguingly, while SIRT1 was shown to regulate c-MYC in Flt3-ITD mutated leukemia [39], it has been demonstrated to regulate Mxd1 in malignant melanoma [42]. Similarly, we found that Mnt and Miz-1 were also downregulated in Flt3-ITD MPs. Of note, Miz-1 serves as a platform to inhibit the expression of cell cycle regulators ([43, 44]). Flt3-ITD mutated leukemic cells have enhanced activity of Cdc25, which overrides the replication checkpoint leading to arrest in the S phase [45]. These findings could point to the possibility that reduced levels of Miz-1 result in enhanced activity of Cdc25 thereby deregulating the cell cycle in Flt3-ITD leukemia. Given that compromised DNA damage response and weakened cell cycle checkpoint promote the progression of AML, our data points to the potential role of Myc and Miz-1 in regulating these pathways in Flt3-ITD leukemia.

As the phosphorylation status of FLT3 is associated with its functional activity [46], the inhibition of FLT3 phosphorylation will affect FLT3-dependent pathways such as RAS/MAPK, JAK/STAT, and Wnt pathways [9]. Given that Myc oncogenes are downstream effectors of these pathways and based on our results that Myc oncogenes are altered upon ITD mutation in FLT3, we hypothesized that modulation of FLT3 phosphorylation will result in transcriptional reprogramming of the Myc network. Our data showed that PKC412-mediated inhibition of FLT3 signaling increased Mxd1 and Mxd2 expression, as well as the expression of Mxd4 and Mnt to a lesser degree, while it reduced cMyc expression in Flt3-ITD AML cells. During the course of preparation of this manuscript, Zhang et al. reported that PKC412-induced Myc downregulation results in decreased telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) activity [47]. Additionally, inhibition of cMyc has several therapeutic implications in solid tumors and hematological malignancies. It has been reported that cMyc inhibition overcomes radio- and chemotherapy resistance in pediatric medulloblastoma [48]. Similarly, cMyc inhibition has been shown to negatively impact lymphoma growth [49] and overcome drug-resistant AML [33]. Furthermore, cMyc inhibition prevents leukemia initiation in mice and impairs the growth of relapsed and induction failure pediatric T-ALL cells [50]. Our data showed that selective inhibition of Flt3-ITD downstream signaling induced c-Myc inhibition, which is consistent with a recent report [47]. Furthermore, our data also shows that Mnt and Miz-1 of the Mxd family are targets of Flt3-ITD signaling pointing to the Myc network as a whole being a target of activated Flt3-ITD. Additionally, our data showed that nMyc expression is increased in LSK, MPP, and pre-GM cells from Flt3-ITD mice. Reports supporting the important role of the inhibition of the Mxd family of tumor suppressors include studies showing that Mxd1 promotes cell cycle arrest and differentiation [30]; also, several studies showed deletion of the 10q24-q25 chromosome, where the MXD2 gene is located in solid tumors [51]. Furthermore, MXD2 is mutated in hematological malignancies [52], as well as in solid tumors. Interestingly, reintroduction of Mxd2 in glioblastoma cells deficient in Mxd2 results in reduced glioblastoma cell growth and clonogenicity [53]. Our study points to the fact that alterations in the Myc network by Flt3-ITD signaling are involved in myeloid leukemogenesis and that PKC412-mediated Flt3-ITD inhibition partly exerts its antileukemic activity by affecting the Myc/Max/Mxd network.

Acknowledgments

A. H. is supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Pediatric Cancer Society, and the Swedish Society of Physicians. The work was also supported by the Lions Foundation, Skåne, Sweden; Georg Danielsson's fund for blood disease; the Physician Society of Lund; Olof Eliasson's Foundation; the Crafoord Foundation; the Knut and Alice Wallenbergs Foundation; the Royal Physiographic Society; and the Lundberg Research Foundation. We thank the members of the Stein Eirik Jacobsen Laboratory for their helpful discussions. We thank Lilian Wittman, Zhi Ma, and Anna Fossum for their excellent technical support.

Data Availability

The Q-RT-PCR data and flow cytometry data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contributions

F. B. and A. H. conceived the project, designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. F. B., M. A., and A. H. performed the experiments. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Luskin M. R., DeAngelo D. J. Midostaurin/PKC412 for the treatment of newly diagnosed FLT3 mutation-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Review of Hematology. 2017;10(12):1033–1045. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2017.1397510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandts C. H., Sargin B., Rode M., et al. Constitutive activation of Akt by Flt3 internal tandem duplications is necessary for increased survival, proliferation, and myeloid transformation. Cancer Research. 2005;65(21):9643–9650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Duhier F. M., Goodeve A. C., Wilson G. A., et al. FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations in adult acute myeloid leukaemia define a high-risk group. British Journal of Haematology. 2000;111(1):190–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiede C., Steudel C., Mohr B., et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99(12):4326–4335. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.12.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hospital M. A., Green A. S., Maciel T. T., et al. FLT3 inhibitors: clinical potential in acute myeloid leukemia. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2017;10:607–615. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S103790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swords R., Freeman C., Giles F. Targeting the FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26(10):2176–2185. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhary C., Schwable J., Brandts C., et al. AML-associated Flt3 kinase domain mutations show signal transduction differences compared with Flt3 ITD mutations. Blood. 2005;106(1):265–273. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tickenbrock L., Schwable J., Wiedehage M., et al. Flt3 tandem duplication mutations cooperate with Wnt signaling in leukemic signal transduction. Blood. 2005;105(9):3699–3706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim K. T., Baird K., Davis S., et al. Constitutive Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 activation results in specific changes in gene expression in myeloid leukaemic cells. British Journal of Haematology. 2007;138(5):603–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., Zhang X., Xie W., Li X., Huang S. MYC-mediated synthetic lethality for treatment of hematological malignancies. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2015;15(1):53–70. doi: 10.2174/1568009615666150105120055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schick M., Habringer S., Nilsson J. A., Keller U. Pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting of aberrant MYC expression in haematological cancers. British Journal of Haematology. 2017;179(5):724–738. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sommer A., Bousset K., Kremmer E., Austen M., Luscher B. Identification and characterization of specific DNA-binding complexes containing members of the Myc/Max/Mad network of transcriptional regulators. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(12):6632–6642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herold S., Wanzel M., Beuger V., et al. Negative regulation of the mammalian UV response by Myc through association with Miz-1. Molecular Cell. 2002;10(3):509–521. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawagoe H., Kandilci A., Kranenburg T. A., Grosveld G. C. Overexpression of N-Myc rapidly causes acute myeloid leukemia in mice. Cancer Research. 2007;67(22):10677–10685. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delgado M. D., Albajar M., Gomez-Casares M. T., Batlle A., Leon J. MYC oncogene in myeloid neoplasias. Clinical & Translational Oncology. 2013;15(2):87–94. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheijen B., Ngo H. T., Kang H., Griffin J. D. FLT3 receptors with internal tandem duplications promote cell viability and proliferation by signaling through Foxo proteins. Oncogene. 2004;23(19):3338–3349. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delpuech O., Griffiths B., East P., et al. Induction of Mxi1-SRα by FOXO3a contributes to repression of Myc-dependent gene expression. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2007;27(13):4917–4930. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01789-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laurenti E., Varnum-Finney B., Wilson A., et al. Hematopoietic stem cell function and survival depend on c-Myc and N-Myc activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(6):611–624. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee B. H., Tothova Z., Levine R. L., et al. FLT3 mutations confer enhanced proliferation and survival properties to multipotent progenitors in a murine model of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(4):367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sitnicka E., Buza-Vidas N., Ahlenius H., et al. Critical role of FLT3 ligand in IL-7 receptor independent T lymphopoiesis and regulation of lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors. Blood. 2007;110(8):2955–2964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adolfsson J., Månsson R., Buza-Vidas N., et al. Identification of Flt 3+ lympho-myeloid stem cells lacking erythro-megakaryocytic potential a revised road map for adult blood lineage commitment. Cell. 2005;121(2):295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiel M. J., Yilmaz O. H., Iwashita T., Yilmaz O. H., Terhorst C., Morrison S. J. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121(7):1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pronk C. J. H., Rossi D. J., Månsson R., et al. Elucidation of the phenotypic, functional, and molecular topography of a myeloerythroid progenitor cell hierarchy. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(4):428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kharazi S., Mead A. J., Mansour A., et al. Impact of gene dosage, loss of wild-type allele, and FLT3 ligand on Flt3-ITD-induced myeloproliferation. Blood. 2011;118(13):3613–3621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang G., Hurlin P. J. MNT and emerging concepts of MNT-MYC antagonism. Genes (Basel) 2017;8(2) doi: 10.3390/genes8020083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu S. H., Heiser D., Li L., et al. FLT3-ITD knockin impairs hematopoietic stem cell quiescence/homeostasis, leading to myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(3):346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weisberg E., Boulton C., Kelly L. M., et al. Inhibition of mutant FLT3 receptors in leukemia cells by the small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKC412. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(5):433–443. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams C. B., Kambhampati S., Fiskus W., et al. Preclinical and phase I results of decitabine in combination with midostaurin (PKC412) for newly diagnosed elderly or relapsed/refractory adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(12):1341–1352. doi: 10.1002/phar.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sasine J. P., Schiller G. J. Emerging strategies for high-risk and relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia: novel agents and approaches currently in clinical trials. Blood Reviews. 2015;29(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diolaiti D., McFerrin L., Carroll P. A., Eisenman R. N. Functional interactions among members of the MAX and MLX transcriptional network during oncogenesis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2015;1849(5):484–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oppedal B. R., Oien O., Jahnsen T., Brandtzaeg P. N-myc amplification in neuroblastomas: histopathological, DNA ploidy, and clinical variables. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1989;42(11):1148–1152. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.11.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hooker C. W., Hurlin P. J. Of Myc and Mnt. Journal of Cell Science. 2006;119(2):208–216. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan X. N., Chen J. J., Wang L. X., et al. Inhibition of c-Myc overcomes cytotoxic drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia cells by promoting differentiation. PLoS One. 2014;9(8, article e105381) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mead A. J., Kharazi S., Atkinson D., et al. FLT3-ITDs instruct a myeloid differentiation and transformation bias in lymphomyeloid multipotent progenitors. Cell Reports. 2013;3(6):1766–1776. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mead A. J., Neo W. H., Barkas N., et al. Niche-mediated depletion of the normal hematopoietic stem cell reservoir by Flt3-ITD–induced myeloproliferation. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2017;214(7):2005–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porter S. N., Cluster A. S., Yang W., et al. Fetal and neonatal hematopoietic progenitors are functionally and transcriptionally resistant to Flt3-ITD mutations. eLife. 2016;5, article e18882 doi: 10.7554/elife.18882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Müller T. A., Grundler R., Istvanffy R., et al. Lineage-specific STAT5 target gene activation in hematopoietic progenitor cells predicts the FLT3+-mediated leukemic phenotype. Leukemia. 2016;30(8):1725–1733. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson A., Murphy M. J., Oskarsson T., et al. c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes & Development. 2004;18(22):2747–2763. doi: 10.1101/gad.313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L., Osdal T., Ho Y., et al. SIRT1 activation by a c-MYC oncogenic network promotes the maintenance and drug resistance of human FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(4):431–446. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muvarak N., Kelley S., Robert C., et al. c-MYC generates repair errors via increased transcription of alternative-NHEJ factors, LIG3 and PARP1, in tyrosine kinase-activated leukemias. Molecular Cancer Research. 2015;13(4):699–712. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morris V. A., Cummings C. L., Korb B., Boaglio S., Oehler V. G. Deregulated KLF4 expression in myeloid leukemias alters cell proliferation and differentiation through microRNA and gene targets. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2016;36(4):559–573. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00712-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meliso F. M., Micali D., Silva C. T., et al. SIRT1 regulates Mxd 1 during malignant melanoma progression. Oncotarget. 2017;8(70):114540–114553. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phan R. T., Saito M., Basso K., Niu H., Dalla-Favera R. BCL6 interacts with the transcription factor Miz-1 to suppress the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p 21 and cell cycle arrest in germinal center B cells. Nature Immunology. 2005;6(10):1054–1060. doi: 10.1038/ni1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basu S., Liu Q., Qiu Y., Dong F. Gfi-1 represses CDKN2B encoding p15INK4B through interaction with Miz-1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(5):1433–1438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804863106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seedhouse C., Grundy M., Shang S., et al. Impaired S-phase arrest in acute myeloid leukemia cells with a FLT3 internal tandem duplication treated with clofarabine. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(23):7291–7298. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meshinchi S., Appelbaum F. R. Structural and functional alterations of FLT3 in acute myeloid leukemia. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(13):4263–4269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X., Li B., Yu J., et al. MYC-dependent downregulation of telomerase by FLT3 inhibitors is required for their therapeutic efficacy on acute myeloid leukemia. Annals of Hematology. 2018;97(1):63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-3158-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.von Bueren A. O., Shalaby T., Oehler-Jänne C., et al. RNA interference-mediated c-MYC inhibition prevents cell growth and decreases sensitivity to radio- and chemotherapy in childhood medulloblastoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):p. 10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomez-Curet I., Perkins R. S., Bennett R., Feidler K. L., Dunn S. P., Krueger L. J. c-Myc inhibition negatively impacts lymphoma growth. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2006;41(1):207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roderick J. E., Tesell J., Shultz L. D., et al. c-Myc inhibition prevents leukemia initiation in mice and impairs the growth of relapsed and induction failure pediatric T-ALL cells. Blood. 2014;123(7):1040–1050. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-522698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawamata N., Park D., Wilczynski S., Yokota J., Koeffler H. P. Point mutations of the Mxil gene are rare in prostate cancers. Prostate. 1996;29(3):191–193. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(199609)29:3<191::AID-PROS2990290305>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo X. L., Pan L., PhD, MD, Zhang X. J., et al. Expression and mutation analysis of genes that encode the Myc antagonists Mad 1, Mxi 1 and Rox in acute leukaemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2007;48(6):1200–1207. doi: 10.1080/10428190701342018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wechsler D. S., Shelly C. A., Petroff C. A., Dang C. V. MXI1, a putative tumor suppressor gene, suppresses growth of human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Research. 1997;57(21):4905–4912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The Q-RT-PCR data and flow cytometry data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.