Abstract

Ultrasound super-resolution (SR) microvessel imaging technologies are rapidly emerging and evolving. The unprecedented combination of imaging resolution and penetration promises a wide range of preclinical and clinical applications. This study concerns spatial quantization error in SR imaging, a common issue that involves a majority of current SR imaging methods. While quantization error can be alleviated by the microbubble localization process (e.g., via upsampling or parametric fitting), it is unclear to what extent the localization process can suppress the spatial quantization error induced by discrete sampling. It is also unclear when low spatial sampling frequency will result in irreversible quantization errors that cannot be suppressed by the localization process. This study had two goals: 1) to systematically investigate the effect of quantization in SR imaging and establish principles of adequate SR imaging spatial sampling that yield minimal quantization error with proper localization methods; 2) to compare the performance of various localization methods and study the level of tolerance of each method to quantization. We conducted experiments on a small wire target and on a microbubble flow phantom. We found that Fourier analysis of an oversampled spatial profile of the microbubble signal could provide reliable guidance for selecting beamforming spatial sampling frequency. Among various localization methods, parametric Gaussian fitting and centroid-based localization on upsampled data had better microbubble localization performance and were less susceptible to quantization error than peak intensity-based localization methods. When spatial sampling resolution was low, parametric Gaussian fitting-based localization had the best performance in suppressing quantization error, and could produce acceptable SR microvessel imaging with no significant quantization artifacts. The findings from this paper can be used in practice to help intelligently determine the minimum requirement of spatial sampling for robust microbubble localization to avoid adding or even reduce the burden of computational cost and data storage that are commonly associated with SR imaging.

INTRODUCTION

The field of microbubble-based super-resolution (SR) microvessel imaging has been rapidly growing [1–16]. Early work by Couture et al. in 2011 [1] and Desailly et al. in 2013 [2] reported microbubble super-localization methods based on pre-beamforming radiofrequency (RF) data, where isolated microbubbles manifest in the form of an “RF parabola”. By fitting the RF parabola with the equation of time-of-flight of ultrasound, the center locations of microbubbles can be determined and utilized to form SR microvessel images. In 2013, Viessmann et al. [3] and O’Reilly et al. [4] independently demonstrated the use of the center location of post-beamforming microbubble signals to achieve SR imaging. The post-beamforming microbubble signals appear as blurred blobs that resemble the point spread function (PSF) of the ultrasound system. Recent work published by Christensen-Jeffries et al. [5] and Errico et al. [6] in 2015 used similar principles in the domain of the post-beamforming signal to locate the center of microbubbles for SR imaging, albeit with different imaging strategies of creating isolated microbubble signals. Christensen-Jeffries et al. used conventional low frame-rate scanning and diluted microbubbles, while Errico et al. used ultrafast plane wave imaging and non-diluted microbubbles. Since 2015, follow-up works by various groups quickly emerged to study and improve the SR imaging technology. These studies primarily concentrated on the post-beamforming signal domain and investigated topics of motion correction [15], microbubble signal denoising [12], microbubble tracking [7, 12], microbubble detection [16], and temporal resolution of SR imaging [11]. In this paper, we focus on the same theme of post-beamforming SR imaging and use the term SR imaging to refer to this group of methods.

A common processing step in SR imaging is microbubble localization, which involves using the ultrasound data sampled at a lower resolution grid to determine the microbubble location at a higher resolution grid. Localization can be done either based on the centroid or the peak intensity of the microbubble signal [6, 9, 12, 13, 15], or by parametric fitting (e.g., Gaussian fitting) of the microbubble data to come up with an analytical solution of the microbubble signal [5]. For centroid and peak intensity-based localization methods, upsampling via interpolation is often necessary to suppress quantization error and facilitate accurate localization [6, 12, 13]. This is because normally, ultrasound data sampling and beamforming are optimized to the wavelength of ultrasound, which is typically two orders of magnitude larger than the size of the microbubbles (~2–6 μm). Although in theory, the ideal way of minimizing quantization error caused by discrete sampling is to increase the sampling rate in the axial direction and the number of imaging lines in the lateral direction, in practice, however, increasing the sampling rate of either the pre-beamforming raw channel data or the post-beamforming image data may not be a trivial task for many ultrasound systems. Also, for conventional line-by-line scanning systems, increasing lateral sampling rate involves increasing scanning line density, which may significantly decrease imaging frame rate. Even for ultrafast plane wave imagers where scan lines are virtual and software beamformers allow reconstruction of data on any sized grid at any spatial locations [17], it may not be practically feasible to conduct beamforming on very fine pixel grids because of the high beamforming computational cost (roughly scaled by the number of beamformed pixels) and the enormous data size. These are already critical challenges of SR imaging due to the large amount of data frames that need to be acquired and accumulated. Therefore, a reliable and accurate microbubble localization method that is least susceptible to quantization error is crucial in practice to facilitate robust SR imaging.

At present, however, there is little knowledge of the extent to which processes such as interpolation and parametric fitting that are commonly used in localization can remove quantization error. It is also unclear how to determine the lower limit of the spatial sampling frequency, below which the quantization error becomes irreversible. In addition, it is unclear which localization method is most effective in suppressing quantization error (especially under the conditions of low spatial sampling), and how to optimize the spatial sampling frequency to balance the tradeoff between quantization error and beamforming cost (or imaging frame rate in the case of line-by-line scanning). These are important guidelines in practice for beamforming and saving optimal amount of data to avoid adding or even reduce the burden of computational cost and data size for SR imaging.

To fill these gaps, in this study, we systematically investigated the effects of quantization error induced by different spatial sampling frequencies and studied the performance of various localization methods in suppressing the quantization error. The objectives of this study were two-fold: 1) to establish the principles of adequate spatial sampling for SR imaging and study requirements of spatial sampling resolution that guarantee minimal quantization error by proper upsampling; 2) to compare the robustness of various localization approaches under different spatial sampling conditions, and study the level of tolerance of each method to low spatial sampling. The overall goal was to provide general guidelines for choosing the optimal spatial sampling frequency and the localization method to best suit the needs and capabilities of different SR imaging applications.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: in the Materials and Methods section, we introduce the experiment setups and SR processing methods for the wire target study and the microbubble flow phantom study. We then show results of each section of the study in the Results section. We finalize the paper with discussion and conclusions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All the studies conducted in this paper were performed on the Verasonics Vantage system (Verasonics Inc., Kirkland, WA), which is a software beamforming scanner that is capable of flexibly adjusting the spatial sampling frequency and defining arbitrary spatial sampling positions [17]. The Verasonics system also provides a simulation mode that allows repeated retrospective beamforming of the same set of channel RF data using arbitrary grid sizes and locations. These features provide an ideal tool for studying quantization error in SR imaging. The knowledge and conclusions gained from these studies, however, are not necessarily restricted to the Verasonics system and can be easily generalized to other imaging systems.

A. Wire Target Study I

For this part of the study, a 10–0 surgical suture with a diameter of 20 μm was used as a point target. The suture was fixed on a frame, which was mounted on a three-axis scanning stage (Motion Controls, Inc., Delano, MN) and submerged in degassed water. The scanning stage provides a minimum step size of 2.5 μm in all three axes. For ultrasound imaging, a Verasonics L11–4v linear array transducer (Verasonics Inc., Kirkland, WA) was used to scan the cross-section of the suture wire, which was positioned at the center of the field-of-view at approximately 20 mm depth. A 10-angle coherent compounding (step angle = 1°) plane wave imaging was used [18] with a single-cycle, 8 MHz pulse for each transmit angle. The received channel RF signal was sampled at 35.71 MHz, which was given by the master clock 250 MHz divided by 7. For pixel-oriented beamforming, the center position of each beamforming pixel (Fig. 1) is used to calculate the round-trip time-of-flight between the pixel center and each element of the transducer, based on which the time delay for each receive channel is determined to fetch the RF data corresponding to the pixel center. Prior to delay-and-sum beamforming, each channel RF data was interpolated by 4 times to reduce timing error in delay calculation, which effectively increases the original RF data sampling rate to approximately 142.86 MHz. In this study, considering the high RF data sampling rate and the multi-channel averaging effect of sampling error, the potential quantization error coming from RF sampling was neglected. Only quantization error as a result of the selection of beamforming pixel size was investigated hereafter.

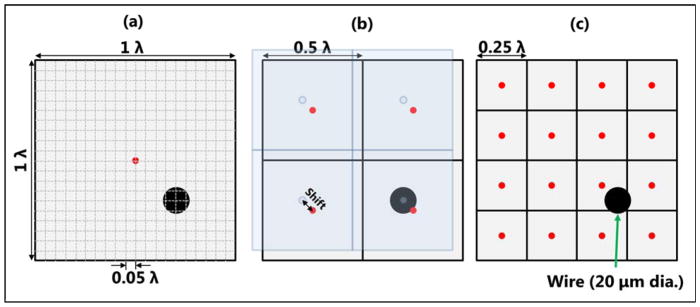

Figure 1.

Schematic plots of different beamforming pixel sizes with relation to the wire target. The pixel size is defined with respect to the size of the ultrasound wavelength (λ). The red dots indicate the center location of each pixel used to calculate time-of-flight of ultrasound for delay-and-sum beamforming. The blue area in (b) indicates the shifted grid for aligning the center of the pixel with the center of the wire target.

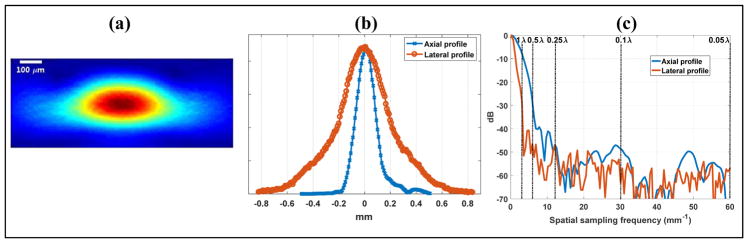

For the first part of the wire target study in this section, the wire target was first beamformed on a very fine pixel grid with 0.05 λ (1 λ ≈ 165.8 μm) resolution (Fig. 1(a)) to establish a reference (i.e., ground truth) to study quantization error. The 2D B-mode image and the 1D profiles of the wire target are shown in Figs. 2(a) and (b), respectively. Because the size of the wire is approximately 10 times smaller than the wavelength of ultrasound at 8 MHz, the wire image essentially represents the PSF of this particular imaging system and sequence. Figure 2(c) shows the Fourier spectra of the axial and lateral profiles of the wire, together with indications of spatial cutoff frequencies corresponding to various beamforming pixel sizes. To study the effects of quantization error for both axial and lateral dimensions, the pixel size along the lateral dimension was first kept at 0.05 λ (i.e., oversampled to minimize quantization error in the lateral dimension), and the same set of RF channel data was beamformed with 0.1 λ, 0.25 λ (Fig. 1(c)), 0.5 λ (Fig. 1(b)), and 1 λ (Fig. 1(a)) axial resolutions. Relative pixel sizes in each dimension are indicated by Fig. 1 (0.1 λ not shown). Due to quantization, the pixel center may or may not be aligned with the center of the wire target. To study the effects of quantization for various distances between the wire target and the pixel center, pixel shifts with 0.05 λ step size were applied to each axial beamforming resolution. On the Verasonics system, this task can be accomplished by adding shifts to the origin of the beamforming grid, which effectively shifts the entire beamforming grid by the same amount (Fig. 1(b)). The finer the size of the beamforming grid, the less pixel shift was required. For example, for 0.1 λ resolution, if the pixel center is overlapped with the wire center at zero-shift, then only one 0.05 λ pixel shift was required to create the case of pixel center not being overlapped with the wire, because the next 0.05 λ pixel shift would put the total amount of pixel shift to 0.1 λ, which would result in an equivalent image as the zero-shift case. For 1 λ resolution, for another instance, a total of 19 shifts were necessary to cover the range of shifts from 0.05 λ to 0.95 λ. The same experiment procedure was repeated for the lateral quantization error study, where the axial pixel size was kept at 0.05 λ resolution and the RF channel data were reconstructed with 0.1 λ, 0.25 λ, 0.5 λ, and 1 λ lateral resolutions.

Figure 2.

(a) Over-sampled B-mode image of the wire target with a spatial resolution of 0.05 λ in both lateral and axial dimensions. (b) 1D axial and lateral profiles of the wire target crossing the peak of the 2D blob. (c) Fourier spectrum of the axial and lateral profiles with indications of sampling frequency cutoffs corresponding to various beamforming pixel sizes.

For each beamforming resolution, the beamformed in-phase quadrature (IQ) data were used to first obtain a B-mode image of the wire. The 1D axial or lateral profile crossing the peak intensity point of the wire target image was extracted. Six different localization methods were studied, including two peak intensity-based methods (one based on cubic interpolation and the other based on spline interpolation), three centroid-based methods (one based on cubic interpolation, one based on spline interpolation, and one based on original data without interpolation), and one parametric Gaussian fitting-based method. For the peak intensity-based methods, 1D cubic interpolation and 1D spline interpolation (i.e., the “interp1.m” function in Matlab) were used to upsample the wire data to 0.05 λ spatial resolution, and the location of the pixel that has the highest intensity value was detected and used as the center location of the wire. The same interpolation schemes were applied to the centroid-based localization methods. The centroid of either the upsampled or original wire signal was calculated following the method introduced in [3]. For the parametric Gaussian fitting-based localization, a parametric fitting in a least-squares sense (i.e., Matlab function “lsqcurvefit.m”) was applied on the original data to derive an analytical solution of the wire signal modeled as a 1D Gaussian function. The Gaussian solution was then used to upsample the wire data to 0.05 λ spatial resolution, followed by peak detection (identical to centroid detection for a Gaussian function). The results from each localization method were compared with the reference wire data beamformed at 0.05 λ to measure quantization error induced by spatial sampling.

B. Wire Target Study II

This part of the study aimed at investigating the effects of quantization error in localizing the moving wire target, mimicking in vivo localization of microbubbles moving in the blood vessel. The wire and motor scanning stage setup allowed precise control of target movement so that the ground truth of movement was known and could be used to measure quantization error. In this study, the wire target was first moved axially away from the origin for 1 mm with a step size of 10 μm, and then moved laterally away from the origin for 1 mm with the same step size. Sufficient waiting time was allowed between wire target movements to ensure that ultrasound acquisition was completed. The same localization methods as in the previous section were used to localize the wire target.

C. Microbubble Flow Phantom Study

This part of the study was designed to validate the findings from the wire target studies by conducting SR imaging of microbubbles in a flow phantom. In this study, a custom made flow phantom (Gammex Inc., Middleton, WI) with a 4 mm inner diameter flow channel was used, which was connected to a syringe pump (Model NE-1010, New Era Pump Systems Inc., Farmingdale, NY) that produced constant flow (flow rate = 12 mL/min, corresponding to an average flow speed of 1.6 cm/s in the 4mm flow channel). The wall material of the flow channel matches the speed of sound of the surrounding background material of the phantom (~1550 m/s). The background material also has a realistic ultrasound attenuation of 0.7 dB/cm/MHz. The flow channel has an oblique angle of 30° with respect to the surface of the phantom. The selected segment of the flow channel for imaging was approximately 2 cm deep. As opposed to previous studies where small diameter (~60 to 200 microns) microtubes or microchannels were used to validate SR imaging [2, 5, 8, 10, 13], a relatively large diameter flow channel was used here because it could provide a larger field-of-view to better visualize the gridding artifacts caused by quantization error. Since the Verasonics allowed repeated retrospective beamforming on the same set of channel data, it was possible to use the high-resolution beamformed data as the ground truth and study the effects of quantization error in our experiment setup. For microbubbles, in this study we used Lumason® (Bracco Diagnostics Inc., Monroe Township, NJ) and diluted the original solution by approximately 1000 times with saline to obtain adequate isolated microbubble signals (~1.5 to 5.6 × 105 microspheres/mL). The same ultrasound imaging sequence as in the wire study was used with a post-compounding pulse-repetition-frequency (PRF) of 500 Hz. A total of 1000 frames (2s data acquisition) of microbubble channel RF data were acquired and stored.

For SR post-processing, a similar method as proposed in [6] and [12] was used. Briefly, a spatiotemporal singular-value-decomposition (SVD) filtering [19] was first applied to the microbubble data to remove background tissue and stationary microbubble signal and extract the decorrelated microbubble signal. A 2D Gaussian low-pass filter was then applied on each frame of the microbubble image to remove noise, followed by a 2D normalized cross-correlation between the smoothed microbubble image and a derived PSF to roughly identify isolated microbubble signals at low spatial resolution. The PSF was created by blurring a delta function with the same 2D Gaussian smoothing filter. After rejecting weak microbubbles with intensity that is −40dB or lower than the maximum bubble signal and microbubbles that were too close to each other, each isolated microbubble signal was extracted using a local window with the size of a single microbubble and localized using the same group of localization methods as in the wire target studies. The 1D interpolation and 1D parametric fitting were correspondingly extended to 2D interpolation and parametric fitting. The original microbubble signal without Gaussian smoothing was used for all the localization processes. Localized microbubble signal was used to form the final SR microvessel density image. No microbubble tracking quality control such as frame-to-frame persistence control or microbubble pairing as introduced in [6] and [12] was used for the purpose of studying quantization error.

RESULTS

A. Wire Target Study I

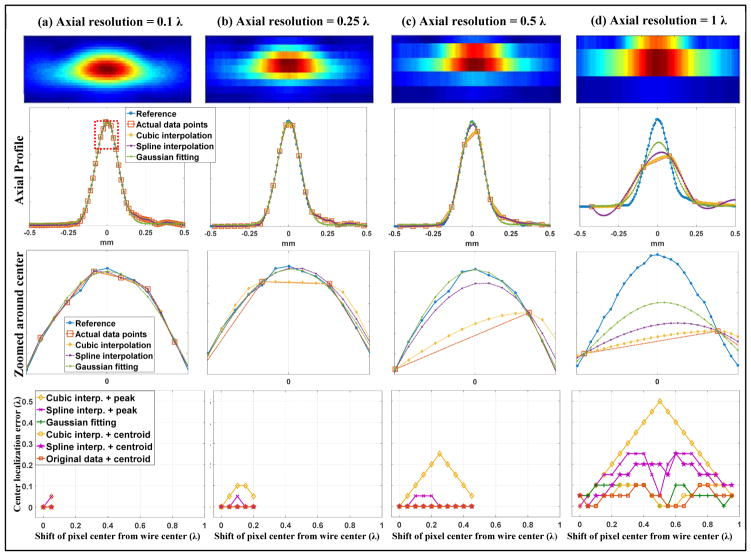

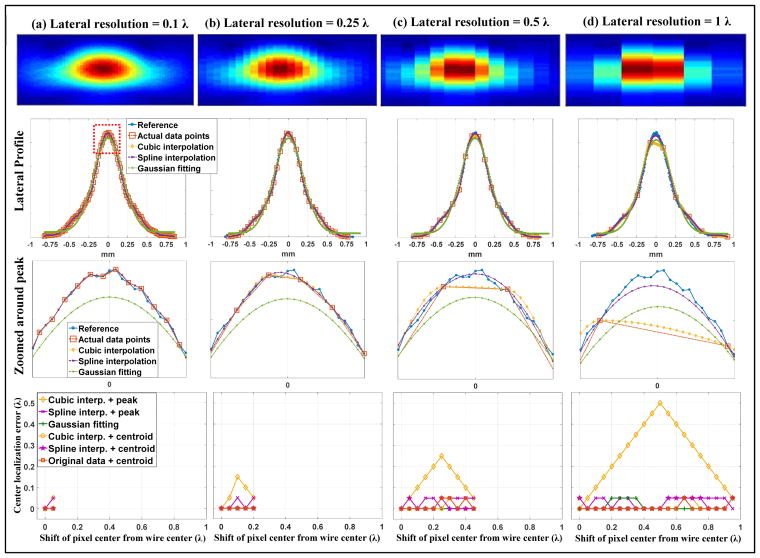

Figures 3 and 4 show the axial and lateral quantization error study results from the wire target. For the axial dimension, as shown in the second row of Fig. 3, all upsampling methods could well recover the full axial profile of the wire up to 0.5 λ axial resolution. At 1 λ axial resolution, only 3 actual samples were available for upsampling, and all methods struggled to recover the waveform. For the case of lateral dimension (second row of Fig. 4), all upsampling methods could well recover the original waveform even at 1 λ resolution. This is due to the wider lateral profile of the wire target image caused by the lower lateral resolution of the ultrasound system. These observations can be explained by the frequency spectrum shown in Fig. 2(c), where one can see that for the axial dimension, a cutoff of 1 λ eliminates a significant portion of the signal (that is, signal with relative energy less than −8 dB) while a 0.5 λ resolution preserves the majority of the signal energy (relative energy greater than −30 dB). For the lateral dimension, on the other hand, if using the same −30 dB cutoff as shown in Fig. 2(c), a 1 λ lateral resolution should be adequate in capturing the majority of the energy of the lateral waveform.

Figure 3.

Axial quantization error study using the wire target. (a)–(d) presents results with different axial sampling resolutions, with the lateral sampling resolution kept at 0.05 λ. The first row shows representative 2D B-mode images of the wire under different sampling conditions. The second row shows representative 1D axial profiles of the wire obtained from the reference data (0.05 λ sampling resolution), the actual data under respective beamforming resolutions, and the upsampled 1D profiles using different localization methods. All profiles presented here were from the worst case scenario where the actual sampling points (i.e., the center location of the beamforming pixel) were farthest away from the center of the wire target. The third row shows the locally magnified 1D profile around the center (indicated by the red dashed box in the first image of the second row). Here the wire target center was identified from the reference data and centered on 0 mm axial location. The fourth row shows the wire target localization error of each localization method under different beamforming pixel resolutions and distances between the pixel center and the center of the wire target.

Figure 4.

Lateral quantization error study using the wire target. The figures are arranged identically to Fig. 3. Readers are referred to the caption of Fig. 3 for descriptions of the figures.

From a closer look of the signals around the center of the wire target profile, as shown in the third row of Figs. 3 and 4, and the localization error measurements for each beamforming resolution, as shown in the fourth row of Figs. 3 and 4, it can be seen that localization methods based on centroid measurements and parametric Gaussian fitting have more robust performance across all resolutions and pixel center shifts than peak intensity-based localization. The comparison is most conspicuous for the case of cubic interpolation, where one can see a significant decrease of localization error from using peaks to using centroids. Between centroid-based localization and Gaussian fitting-based localization, Gaussian fitting had slightly better performance: for resolutions above and equal to 0.5 λ, Gaussian fitting provided zero localization error in both axial and lateral dimensions. Spline interpolation combined with peak or centroid detection and cubic interpolation combined with centroid performed well for axial resolutions equal and beyond 0.5 λ, and for lateral resolutions equal and beyond 1 λ. The largest quantization error was 0.05 λ, which is acceptable and expected because the final upsampled pixel size was also 0.05 λ. Cubic interpolation combined with peak detection, on the other hand, showed the worst performance across the board and produced almost as much quantization error as the original data without upsampling. This can be well perceived from the zoomed-in view in Figs. 3 and 4, where it is clear that the peak of the upsampled wire profile from cubic interpolation always coincides with the actual sample. These results indicate that: 1) to robustly recover the full waveform of the wire target, the axial and lateral beamforming resolution does not need to go beyond 0.5 λ and 1 λ, respectively, if using localization methods based on centroid or parametric Gaussian fitting; 2) for point target localization, the Gaussian fitting method was the most robust and performed well even at low sampling resolutions; 3) Fourier analysis of an oversampled point target profile can serve as guidance to determine the minimum spatial sampling requirement, beyond which little difference exists in terms of fully recovering the original waveform and reducing quantization error in localization.

B. Wire Target Study II

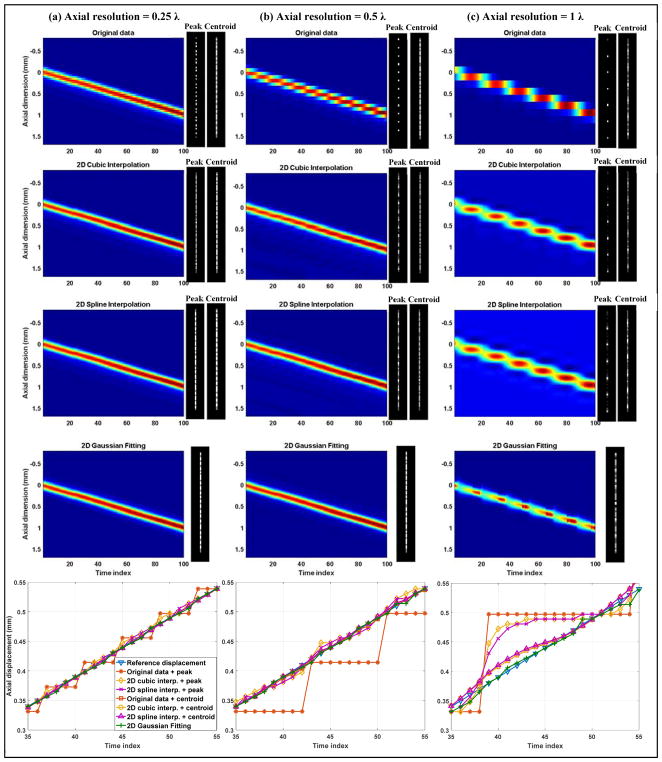

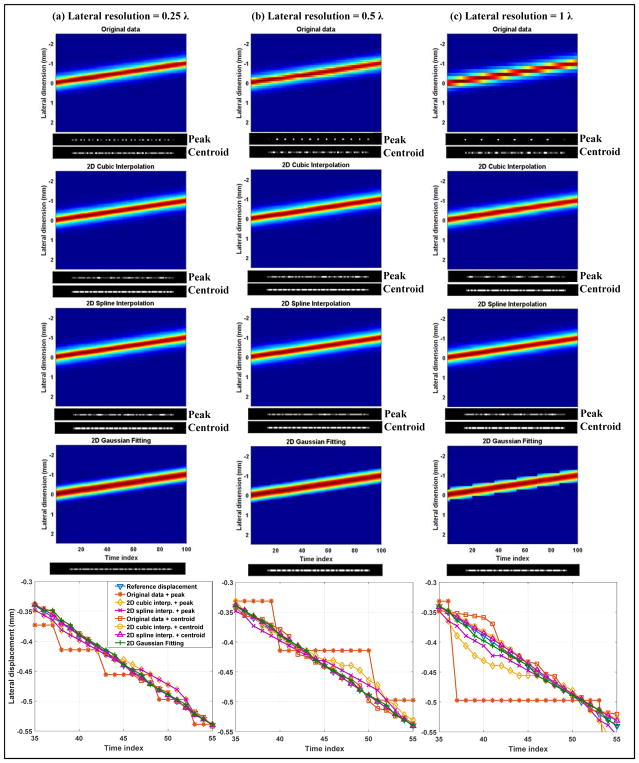

Figures 5 and 6 present the results of the axial and lateral quantization error study of the moving wire target, respectively. The localization error measurements are summarized in Table I. Supplementary videos 1–6 show the original data that recorded the wire movement under different beamforming resolutions. The first row of Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 shows the spatiotemporal data of the wire movement under different resolutions. Together with observations from Supplementary videos 1–6, one can see that when the resolution is low, the wire appears to move discontinuously and “stays” at one pixel location for a considerate amount of time before “jumping” to the next pixel location. This phenomenon gradually disappeared with higher sampling resolution. If using the original data and the peak intensity location to form SR localization images without upsampling, the resulting images (shown in the figures on the right hand side [for axial results] or on the bottom side [for lateral results] of each spatiotemporal movement data) can have significant grid-patterned artifacts. This can also be observed from the last row of Fig. 5 and Fig. 6, where one can see a “stair-shaped” moving target localization trajectory even though the underlying path should be a straight line. At 1 λ axial resolution, the quantization artifacts could not be alleviated by peak intensity-based localization using either cubic or spline interpolation. However, centroid-based localization and the Gaussian fitting method were able to substantially reduce the quantization error, as shown in the fourth and fifth row of Fig. 5 and the root-mean-square error (RMSE) measurements in Table I. This result is in good agreement with the quantization error analysis in Fig. 3(d). After reaching 0.5 λ resolution, all the centroid-based localization methods and the Gaussian fitting-based method essentially produced quantization error-free localization. Little improvement could be gained by further improving the resolution to 0.25 λ, which is again in good agreement with the results shown in the previous section. Without upsampling, centroid estimation needed a beamforming resolution of at least 0.5 λ to avoid significant quantization error. For peak intensity-based localization methods, a 0.25 λ axial resolution was needed to obtain similar quantization error as centroid- and Gaussian fitting-based methods. For the case of lateral localization, as shown in Fig. 6, 1 λ beamforming pixel resolution was adequate for Gaussian fitting-based localization to suppress the quantization error. Centroid detection based on cubic and spline interpolation had the best performance with 0.5 λ and 0.25 λ beamforming resolution. Peak intensity-based approaches still had inferior performance to their counterparts based on centroid detection. Combining the axial and lateral study results, as shown in Table I, parametric Gaussian fitting had the smallest quantization error when spatial sampling frequency was the lowest, and centroid-based localization on upsampled data had the best localization performance when the point target was adequately sampled based on the Fourier analysis.

Figure 5.

Study of quantization error along the axial dimension in localizing a moving wire in the water tank. The three columns correspond to three different axial beamforming resolutions. The first to fourth row show spatiotemporal images of the moving wire obtained from different upsampling methods (denoted in each figure title). The wire was moved towards the positive axial direction for 1 mm with a 10 μm step size. For each spatiotemporal movement image, a final SR image formed by localizing the peak and the centroid of the wire was displayed on the right hand side. The last row displays the partial wire localizing results (from time index 35 to 55) for different localization methods.

Figure 6.

Study of quantization error along the lateral dimension in localizing a moving wire in the water tank. The three columns correspond to three different lateral beamforming resolutions. The first to fourth row show spatiotemporal images of the moving wire obtained from different upsampling methods (denoted in each figure title). The wire was moved towards the negative lateral direction for 1 mm with a 10 μm step size. For each spatiotemporal movement image, a final SR image formed by localizing the peak and the centroid of the wire was displayed on the bottom side. The last row displays the partial wire localizing results (from time index 35 to 55) for different localization methods.

Table I.

Summary of root-mean-square error (RMSE) of wire target localization

| Axial quantization error (μm) | 0.25 λ | 0.5 λ | 1 λ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original data (no upsampling) and peak detection | 12.10 | 48.14 | 62.58 |

| 2D cubic interpolation and peak detection | 3.68 | 8.80 | 46.58 |

| 2D spline interpolation and peak detection | 3.27 | 5.37 | 42.64 |

| Original data (no upsampling) and centroid detection | 2.62 | 3.48 | 10.78 |

| 2D cubic interpolation and centroid detection | 2.66 | 2.53 | 11.00 |

| 2D spline interpolation and centroid detection | 2.66 | 2.51 | 12.49 |

| 2D Gaussian fitting | 3.54 | 4.20 | 6.27 |

|

| |||

| Lateral quantization error (μm) | 0.25 λ | 0.5 λ | 1 λ |

|

| |||

| Original data (no upsampling) and peak detection | 20.62 | 35.96 | 74.40 |

| 2D cubic interpolation and peak detection | 8.80 | 12.67 | 22.48 |

| 2D spline interpolation and peak detection | 8.70 | 6.73 | 10.98 |

| Original data (no upsampling) and centroid detection | 3.69 | 8.06 | 12.78 |

| 2D cubic interpolation and centroid detection | 1.70 | 1.38 | 6.95 |

| 2D spline interpolation and centroid detection | 1.77 | 1.51 | 5.33 |

| 2D Gaussian fitting | 4.19 | 4.23 | 3.85 |

C. Microbubble Flow Phantom Study

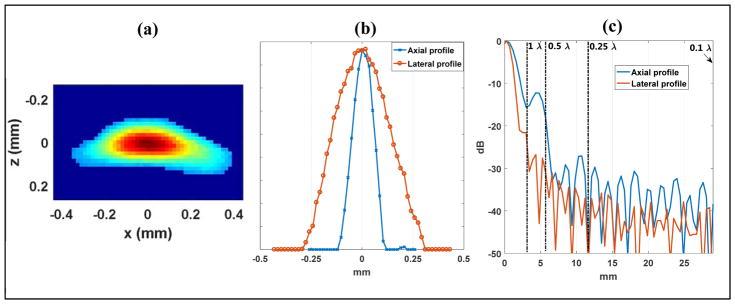

Figure 7 shows a similar Fourier spectrum analysis of a single microbubble as in the wire target study. Using the same −30 dB cutoff threshold, according to Fig. 7(c), a 0.5 λ lateral beamforming resolution and a 0.25 λ axial beamforming resolution should be adequate to fully sample the microbubble waveform without quantization error. Figures 8–10 show the SR imaging results of the flow channel under different beamforming resolutions and using different localization methods. The oversampled 0.1 λ resolution result (Figs. 8(a), 9 (a) and 10 (a)) was used as the reference ground truth. From Fig. 8, one can see that an axial resolution of 0.25 λ and lateral resolution of 0.5 λ indeed provided adequate sampling of the microbubble signal. All localization methods produced comparable results to the oversampled data set. This again validated the use of Fourier spectrum analysis to determine the minimum requirement for SR spatial sampling to suppress quantization error. In practice, it is important to understand that further improving the beamforming resolution beyond the requirement may gain little in localization accuracy while significantly increasing the burden of beamforming and data storage. For example, increasing beamforming resolution from 0.25 λ axial and 0.5 λ lateral to 0.1 λ in both dimensions would increase beamforming computational cost and data size by approximately 12.5 times.

Figure 7.

(a) B-mode image of a single microbubble beamformed with a spatial resolution of 0.1 λ in both lateral and axial dimensions. (b) 1D axial and lateral profiles of the microbubble crossing the summit of the 2D blob. (c) Fourier spectrum of the axial and lateral profiles with indications of sampling frequency cutoffs corresponding to various beamforming pixel sizes.

Figure 8.

SR vessel density images of the flow channel obtained from different microbubble localization methods (b–g, localization methods indicated in the subtitles). The axial and lateral beamforming resolution was both 0.25 λ. For each SR image, a magnified view of a local region inside the channel was displayed (as indicated by the white box on the top left image). To facilitate better visualization of the pixelated SR images, square root compression was applied to each image followed by a modest 2D Gaussian smoothing filter (3 × 3 window, σ = 0.5). The smoothing filter was only applied to the non-zoomed background image. No smoothing filtering was applied to the zoomed local SR images to facilitate better comparisons among various conditions. For the reference data in (a), direct microbubble localization was performed on oversampled data.

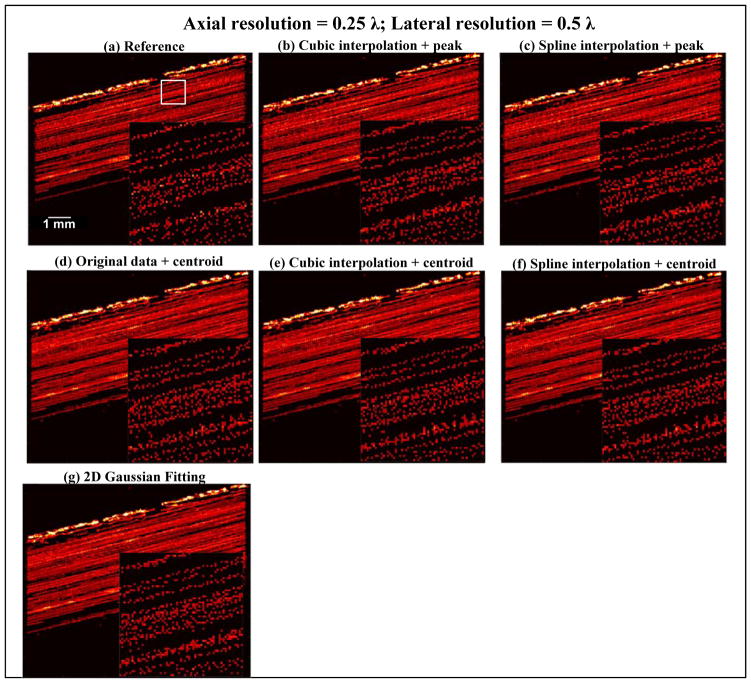

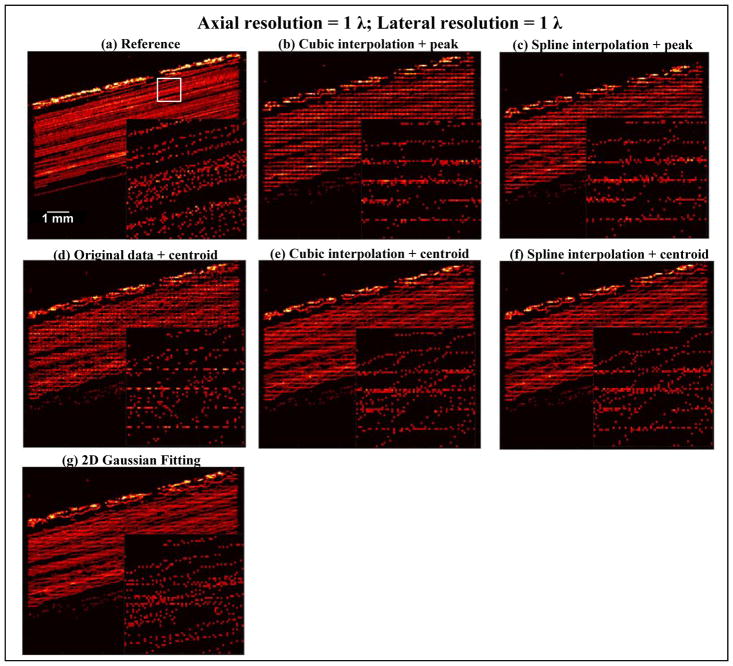

Figure 10.

SR vessel density images of the flow channel obtained from different microbubble localization methods (b–g, localization methods indicated in the subtitles). The axial and lateral beamforming resolution was both 1 λ. For each SR image, a magnified view of a local region inside the channel was displayed (as indicated by the white box on the top left image). To facilitate better visualization of the pixelated SR images, square root compression was applied to each image followed by a modest 2D Gaussian smoothing filter (3 × 3 window, σ = 0.5). The smoothing filter was only applied to the non-zoomed background image. No smoothing filtering was applied to the zoomed local SR images to facilitate better comparisons among various conditions. For the reference data in (a), direct microbubble localization was performed on oversampled data.

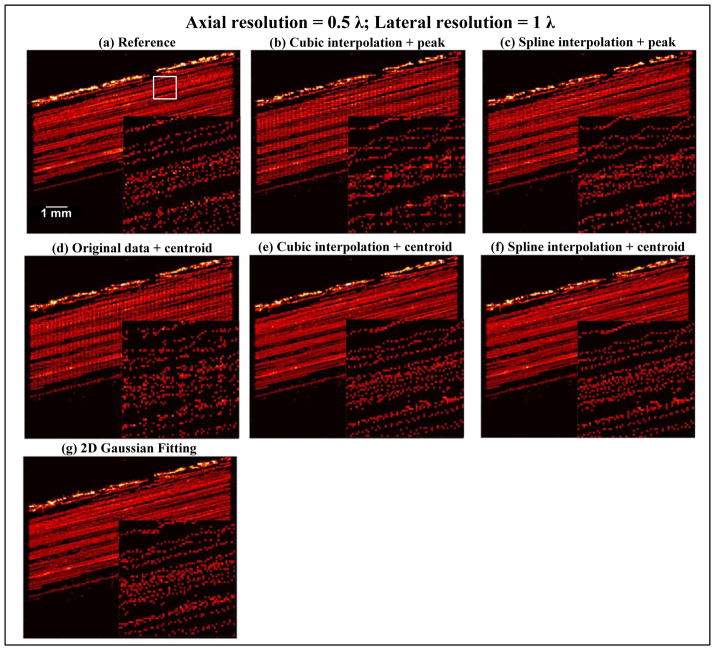

Figure 9.

SR vessel density images of the flow channel obtained from different microbubble localization methods (b–g, localization methods indicated in the subtitles). The axial and lateral beamforming resolution was 0.5 λ and 1 λ, respectively. For each SR image, a magnified view of a local region inside the channel was displayed (as indicated by the white box on the top left image). To facilitate better visualization of the pixelated SR images, square root compression was applied to each image followed by a modest 2D Gaussian smoothing filter (3 × 3 window, σ = 0.5). The smoothing filter was only applied to the non-zoomed background image. No smoothing filtering was applied to the zoomed local SR images to facilitate better comparisons among various conditions. For the reference data in (a), direct microbubble localization was performed on oversampled data.

Interestingly, as shown in Figs. 9 and 10, when decreasing the beamforming resolution to below the minimum requirement, peak intensity-based methods (Figs. 9(b,c) and 10 (b,c)) and centroid detection without upsampling (Figs. 9(d) and 10 (d)) showed significant quantization error, especially for the 1 λ resolution case where these methods were severely hampered by quantization and generated nothing but grid artifacts. Centroid detection with upsampling (Figs. 9(e,f) and 10 (e,f)) and Gaussian fitting (Figs. 9(g) and 10 (g)), on the other hand, tolerated the coarser beamforming resolution significantly better, and did not produce significant grid artifacts even at the 1 λ resolution case. Similar to the observations in the wire target study, Gaussian fitting had the smallest quantization error when spatial sampling frequency was lowest. Although the localization accuracy was reduced by doubling the pixel size in both dimensions as shown from Fig. 9, the gained 4-fold increase in beamforming speed and decrease in data size may justify the modest loss of accuracy when using centroid detection with upsampling or 2D Gaussian fitting for localization. Even for the coarsest resolution at 1 λ (Fig. 10), the performance of Gaussian fitting may still be acceptable for certain applications where only an approximate depiction of microvasculature is needed without high accuracy. Practically this may be an attractive option because it gives another 2-fold decrease in computational cost and data size (a total of 8-fold reduction from the minimum requirement as shown in Fig. 8).

DISCUSSION

Localization is a key step in SR imaging for estimating the center location of microbubbles and generating microvessel images. When spatial sampling is inadequate, localization may be inappropriately done, resulting in severe quantization error (Fig. 10). The results showed in this study demonstrated superior localization performance of centroid-based and parametric Gaussian fitting-based methods as compared to peak intensity-based localization methods. When microbubble signal is adequately sampled, centroid detection using upsampled microbubble signal provided the best localization performance. When microbubble signal is not adequately sampled, parametric Gaussian fitting was demonstrated to be least susceptible to quantization error. This is not surprising because it is long-established that model-based parametric estimation has robust performance in discretely sampled signals with scarce data points [20]. In the cases of 1 λ pixel resolution showed in this study, there may be only 2 – 3 samples actually acquired per microbubble waveform, which can make it challenging for nonparametric methods to arrive at the correct solution.

Interestingly, as indicated by the result shown in Fig. 3(d) from the first part of the wire study, if the peak or the centroid location of the waveform is used to estimate the target location, Gaussian fitting or measuring the centroid based on upsampled waveforms could still provide arguably acceptable localization results at spatial sampling frequencies below the minimum requirement (also observed in Fig. 10). However, as recently pointed out by Christensen-Jeffries et al. [13], microbubble signal onset may provide more accurate microbubble location estimates than the peak or centroid due to variable microbubble signal appearances caused by different microbubble resonance, size, partial volume effects, etc. For this application, adequate spatial sampling that satisfies the minimum requirement established in this study may be necessary to accurately sample the onset portion of the microbubble signal, unless a modeled parametric fitting specifically targeting the onset of microbubble signal is derived. We defer this to future work because in this study we focused on using the peak and centroid location of the point target for SR imaging.

The findings in this study have several practical implications. First, for in vivo SR imaging especially for humans, the amount of imaging time involved with contrast microbubbles is limited (typically 1–2 minutes per bolus of microbubble injection [21]). Combined with the unique needs of accumulation of large quantity of microbubble signals, ideally SR imaging needs to be continuous. This may not be an issue for conventional scanners, but can be challenging for ultrafast plane wave imaging with high beamforming computational cost and data generation rate. In addition, human imaging provides an even worse circumstance due to the large field-of-view (FOV) of imaging that directly translates to more pixels that need to be beamformed and stored. For a software beamforming system like Verasonics where retrospective beamforming is allowed, saving the pre-beamformed RF channel data may be an option (thus avoiding beamforming during live scan), however the RF channel data size can be very large and burdensome to transfer and store in real-time. Therefore, it is practically meaningful to understand the minimum requirement of spatial sampling to best distribute the available and sometimes limited resources for SR imaging. Second, microbubble imaging involves versatile imaging sequences such as the various nonlinear imaging methods that are still rapidly evolving. In practice, one can use the Fourier analysis approach to analyze the typical PSF of a particular imaging sequence from a particular imaging system to determine the spatial beamforming sampling frequency. For example, subharmonic imaging may be more immune to quantization error due to the lower frequency and longer wavelength, while second or third harmonics may be more susceptible. Lastly, the findings in this study can be easily extended to 3D imaging, where it is anticipated that 3D Gaussian fitting should also be more tolerant to low sampling resolution than interpolation. This can be significant in 3D imaging where the elevational resolution is low and the demand for data processing and storage are at least an order of magnitude higher than 2D imaging.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study we systematically investigated the effect of beamforming spatial quantization on super-resolution (SR) ultrasound microvessel imaging. A general guideline of determining the minimal spatial sampling requirement was proposed by choosing pixel resolutions based on the Fourier analysis of an adequately sampled microbubble data set. Various localization methods were also investigated, among which centroid-based and parametric Gaussian fitting-based localization methods demonstrated better performance than peak intensity-based localization. Gaussian fitting was shown to be least susceptible to quantization error when spatial sampling resolution was low. The findings reported in this study can be used in practice to help determine the optimal spatial sampling strategy that can best accommodate different SR imaging capabilities and applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number K99CA214523. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Couture O, Besson B, Montaldo G, Fink M, Tanter M. Microbubble ultrasound super-localization imaging (MUSLI). 2011 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium; 2011. pp. 1285–1287. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desailly Y, Couture O, Fink M, Tanter M. Sono-activated ultrasound localization microscopy. Applied Physics Letters. 2013;103(17):174107. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viessmann OM, Eckersley RJ, Christensen-Jeffries K, Tang MX, Dunsby C. Acoustic super-resolution with ultrasound and microbubbles. Phys Med Biol. 2013 Sep 21;58(18):6447–58. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/18/6447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Reilly MA, Hynynen K. A super-resolution ultrasound method for brain vascular mapping. Medical Physics. 2013;40(11) doi: 10.1118/1.4823762. 110701-n/a. Art. no. 110701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen-Jeffries K, Browning RJ, Tang MX, Dunsby C, Eckersley RJ. In vivo acoustic super-resolution and super-resolved velocity mapping using microbubbles. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015 Feb;34(2):433–40. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2359650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Errico C, et al. Ultrafast ultrasound localization microscopy for deep super-resolution vascular imaging. Nature. 2015 Nov 26;527(7579):499–502. doi: 10.1038/nature16066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ackermann D, Schmitz G. Detection and Tracking of Multiple Microbubbles in Ultrasound B-Mode Images. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2016 Jan;63(1):72–82. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2015.2500266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin F, Shelton SE, Espindola D, Rojas JD, Pinton G, Dayton PA. 3-D Ultrasound Localization Microscopy for Identifying Microvascular Morphology Features of Tumor Angiogenesis at a Resolution Beyond the Diffraction Limit of Conventional Ultrasound. Theranostics. 2017;7(1):196–204. doi: 10.7150/thno.16899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen KB, et al. Robust microbubble tracking for super resolution imaging in ultrasound. 2016 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS); 2016. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desailly Y, Pierre J, Couture O, Tanter M. Resolution limits of ultrafast ultrasound localization microscopy,” (in English) Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2015 Nov 21;60(22):8723–8740. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/22/8723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bar-Zion A, Tremblay-Darveau C, Solomon O, Adam D, Eldar YC. Fast Vascular Ultrasound Imaging With Enhanced Spatial Resolution and Background Rejection. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2017;36(1):169–180. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2016.2600372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song P, et al. Improved Super-Resolution Ultrasound Microvessel Imaging With Spatiotemporal Nonlocal Means Filtering and Bipartite Graph-Based Microbubble Tracking. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2018;65(2):149–167. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2017.2778941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen-Jeffries K, et al. Microbubble Axial Localization Errors in Ultrasound Super-Resolution Imaging. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 2017;64(11):1644–1654. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2017.2741067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sloun RJGv, Solomon O, Eldar YC, Wijkstra H, Mischi M. Sparsity-driven super-localization in clinical contrast-enhanced ultrasound. 2017 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS); 2017. pp. 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hingot V, Errico C, Tanter M, Couture O. Subwavelength motion-correction for ultrafast ultrasound localization microscopy. Ultrasonics. 2017 May;77:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin F, Tsuruta JK, Rojas JD, Dayton PA. Optimizing Sensitivity of Ultrasound Contrast-Enhanced Super-Resolution Imaging by Tailoring Size Distribution of Microbubble Contrast Agent. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2017 Oct 01;43(10):2488–2493. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daigle RE. Ultrasound imaging system with pixel oriented processing. US20090112095A1. Patent. 2009

- 18.Montaldo G, Tanter M, Bercoff J, Benech N, Fink M. Coherent plane-wave compounding for very high frame rate ultrasonography and transient elastography,” (in English) IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 2009 Mar;(3):489–506. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2009.1067. Article56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demene C, et al. Spatiotemporal Clutter Filtering of Ultrafast Ultrasound Data Highly Increases Doppler and fUltrasound Sensitivity,” (in eng) IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2015 Nov;34(11):2271–85. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2428634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bresler Y, Macovski A. Exact maximum likelihood parameter estimation of superimposed exponential signals in noise. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. 1986;34(5):1081–1089. [Google Scholar]

- 21.LUMASON (sulfur hexafluoride lipid-type A microspheres) for injectable suspension, for intravenous use or intravesical use. 2016 Available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/203684s002lbl.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.