Abstract

INTRODUCTION

While individuals live with dementia for many years, utilization and expenditures from disease onset through the end-of-life period have not been examined in ethnically diverse samples.

METHODS

We used a multiethnic, population-based, prospective study of cognitive aging (Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project) linked to Medicare claims to examine total Medicare expenditures and healthcare utilization among individuals with clinically-diagnosed incident dementia from disease onset to death.

RESULTS

High intensity treatment (hospitalizations, life-sustaining procedures) was common and mean Medicare expenditures per year after diagnosis was $69,000. Non-Hispanic Blacks exhibited higher spending relative to Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites one year after diagnosis. Non-Hispanic Blacks had higher total (mean=$205,000) Medicare expenditures from diagnosis to death compared with non-Hispanic Whites (mean=$118,000). Hispanics’ total expenditures and utilization after diagnosis was similar to Non-Hispanic Whites despite living longer with dementia.

DISCUSSION

Healthcare spending for patients with dementia after diagnosis through the end-of-life is high and varies by ethnicity.

Keywords: End of life care, Medicare expenditures, Alzheimer’s disease costs, Hispanics, health disparities, race/ethnicity

BACKGROUND

The large and growing population of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a major challenge to our healthcare system.1 The cost of caring for individuals with dementia is equal to or higher than the financial burden of heart disease and cancer.2,3 The highest costs for dementia are incurred typically within the last two years of life and are driven by high out-of-pocket costs and informal caregiving needs.2–4 Healthcare utilization at the end-of-life (EOL) is particularly complex for individuals with AD because of challenges with communication about preferences for care and management of complex symptoms.5 Consequently, patients with advanced dementia may have unnecessarily burdensome interventions and more avoidable hospitalizations.6,7

While studies suggest that hospitalizations and Medicare costs are higher for individuals with dementia, especially for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions,8–10 there may be less of a differential increase among the dementia population as individuals approach EOL.11 Furthermore, key factors regarding the role of timing of disease onset, level of comorbidity, and disease severity are understudied, although the severity of dementia and level of comorbidity impact cost of care.12,13 Dementia diagnoses are most often determined via claims data14 which is subject to under-recognition or under-coding, or other measurement limitations. Other studies have relied on probabilistic approaches of dementia likelihood rather than assessing dementia status and severity.2 Most studies are unable to determine timing of dementia onset or level of severity, instead focusing on dementia status at the time of death. While individuals may live with dementia for many years, costs from disease onset through the course of illness including the EOL period (the last year of life) have not been previously examined. Focusing on cases identified at incidence allows for an examination of Medicare-related costs for the entire duration of the disease. Studies of prevalent cases fail to capture cost information available from the early stages of the disease thus potentially underestimating the full consequences of dementia on healthcare utilization and cost.

Additionally, racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare utilization and spending at the EOL have been extensively documented, 15–17 with consistent findings that spending for Blacks are significantly higher than Whites.18–20 These racial disparities at the EOL have not yet been studied in the context of dementia. Furthermore, of particular concern is the expected dramatic growth in the population of Hispanic individuals with dementia—in 2060 there will be 3.6 million Hispanics living with AD.21 Yet many studies fail to include individuals of Hispanic ethnicity or they group all non-White ethnic minorities together in comparison to Whites when assessing racial/ethnic cost differences.

Therefore, we examined Medicare expenditures and healthcare utilization among an incident dementia sample from dementia onset to death. In addition to looking at overall costs in a multiethnic cohort of individuals with clinician-assessed incident dementia diagnoses over the course of disease, we also examined differences by ethnicity. Such work will help fill a critical need in understanding costs associated with dementia and EOL care practices for multiethnic dementia populations

METHODS

Sample

Participants were drawn from the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP), a multiethnic, population-based, prospective study of cognitive aging in Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older residing in a geographically defined area of northern Manhattan. Lists of all Medicare or Medicaid recipients in the study area were provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) at the beginning of study enrollment. Potential subjects were then drawn by stratified random sampling into one of six strata based on age (65–74, 75+) and ethnicity (Hispanics, non-Hispanic Blacks, non-Hispanic Whites based on self-report using 1990 US census format). Subjects were followed in two (1992–1994, 1999–2002) WHICAP cohorts using similar methods. Detailed descriptions of study methodology have been reported previously.22

At the time of study entry, each subject underwent an in-person interview of general health and functional ability, followed by a standardized assessment including medical history, physical and neurological examination, and a neuropsychological battery. After the baseline assessment, subjects were followed at approximately 18-month intervals with similar assessments. Evaluations were conducted in either English or Spanish, based on the primary language or preference of the participant. Recruitment, informed consent and study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center and Columbia University Health Sciences, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the CMS Privacy Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

To obtain data on Medicare utilization and expenditures, individuals were matched to the Medicare Beneficiary Summary file using social security number and Medicare beneficiary ID. The study sample included individuals followed from their first WHICAP visit or the beginning of Medicare data availability (January 1, 1999), and ended at death or end of study follow-up (December 31, 2010). Those enrolled in Medicare Fee-for-Service at the time of dementia onset were included in the current analysis. Among this incident sample, we also identified a subsample of individuals who died during study follow-up with continuous FFS coverage from dementia onset to death the (Supplementary Table 1).

Measures

Dementia Status

At baseline and each follow up, diagnostic conferences were held by a group of neurologists, psychiatrists, and neuropsychologists using results from a neuropsychological battery as well as evidence of impairment in social or occupational function.23,24 A diagnosis of dementia was determined based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, Revised Third Edition criteria.25 The type of dementia was subsequently determined. Diagnosis of probable or possible AD was made based on criteria outlined by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association. Dementia severity was measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR).26 At each assessment, subjects were grouped into three categories, CDR=0 (no dementia), CDR=0.5/1 (mild dementia), and CDR>=2 (moderate/severe dementia). Incident dementia was identified by the date dementia was first identified during the study among those with a previous diagnosis of no dementia.

Healthcare utilization and Medicare expenditures

Healthcare utilization and expenditures each year after diagnosis until death were based on Medicare expenditure data. Medicare expenditure data were obtained from Medicare Standard Analytic Files (SAFs) and included inpatient, outpatient, carrier, durable medical equipment (DME), skilled nursing, home health, and hospice care. Expenditures reflect actual payments from Medicare for all covered services. Expenditures for services that spanned across time periods of interest were apportioned by the number of days that care was received in each period. If an individual died at any point within a year, all expenditures were included in that year for total and annual costs. All expenditures were adjusted to 2017$ using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

Medicare claims were used to identify intensive care unit (ICU) use and days, hospice use, and inpatient hospitalizations. Building upon previous work,27,28 we identified the use of one or more intensive medical procedures in the last month of life, as determined by a review of ICD-9 codes in each decedent’s Medicare claims. These procedures included intubation and mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, gastrostomy tube insertion, enteral or parenteral nutrition, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). We calculated total annual expenditures for each year after incidence and also calculated cumulative expenditures for all Medicare expenditures from date of dementia diagnosis to death.

Subjects’ comorbidities were assessed using a modified Charlson Index of Comorbidity which included myocardial infarct, CHF, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, COPD, arthritis, gastrointestinal disease, mild liver disease, diabetes, chronic renal disease, and systemic malignancy. 29 All items received weights of one, with the exception of chronic renal disease and systemic malignancy, which were weighted two. Individuals’ disability, which may or may not be related to dementia, was measured by difficulties performing various activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) using the Blessed Functional Activity Scale.30

Analyses

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and health care utilization patterns of the sample were reported. We examined Medicare expenditures for all subjects with incident dementia. Analyses were limited to those individuals with fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare at the time of diagnosis in order to calculate expenditures and utilization. Individuals were followed until death or end of study observation period. For the purposes of measuring expenditures and utilization, individuals were censored when they exited FFS Medicare (i.e., enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan). We estimated mean Medicare expenditures by ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White) for each year after diagnosis among the entire sample. We modeled expenditures by ethnicity one year after diagnosis using adjusted generalized linear models (GLM) controlling for dementia severity, age at diagnosis, gender, education, level of comorbidity, total years of follow-up after diagnosis and whether the subject died during observation period.

Next, in order to focus on costs from disease onset to death, we computed total Medicare expenditures and utilization from diagnosis of dementia to death for those who died during study observation with at least 6 months Medicare FFS data available annually. Because expenditures were not distributed normally, we used rank sum tests to compare healthcare utilization (hospital admissions, hospital days, ICU days, hospice days) and Medicare expenditures by ethnicity. Log transformations did not improve normality. Total expenditures from diagnosis through death and years 1–3 after diagnosis were compared by ethnicity using GLM models adjusted for dementia severity, age at death, nursing home status, gender, education, level of comorbidity, and total years of follow-up. For analyses of expenditure data, we examined the appropriateness of distributional family and link functions and chose generalized linear models with gamma family and log link. Rate ratios and average marginal effects were calculated to compare total overall expenditures. The significance level for all tests was set at .05.

RESULTS

A total of 4604 subjects across 2 cohorts were included in the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. 936 (20%) ever had a dementia diagnosis and of these 296 (32%) incident cases were identified between 1999–2010. 186 of these cases had FFS Medicare at the time of diagnosis (62.8%) (heretofore known as ‘full sample’). Of these, 102 died during follow up. Complete FFS data from dementia incidence until death were available for 86 subjects (heretofore known as ‘decedent sample’). (See Supplementary Table 1).

Full sample with incident dementia

Average age at dementia diagnosis of the full sample was 84.3. The majority were female (73%) and one-third had at least a High School education (Table 1). More than half the sample was Hispanic and the remainder were non-Hispanic White (20%) and non-Hispanic Black (25%). The vast majority of individuals (77%) were diagnosed with mild dementia and less than one-third were dependent on at least one ADL. 16 died within one year of diagnosis (8.6%); 21 died 1–2 years after diagnosis (11.3%); and 17 died 2–3 years after diagnosis (9.1%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of full sample at dementia diagnosis (n=186)

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age at diagnosis, mean (SD) | 84.33 (6.26) | |

| Female | 135 | 72.58 | |

| non-Hispanic White | 37 | 19.89 | |

| non-Hispanic Black | 47 | 25.27 | |

| Hispanic | 102 | 54.84 | |

| 12+ years of education | 61 | 32.97 | |

| Lives alone | 58 | 40.85 | |

| Clinical characteristics | Comorbidity Index | 2.34 | 1.53 |

| CHF | 13 | 7.03 | |

| Hypertension | 126 | 68.11 | |

| Stroke | 40 | 21.51 | |

| Diabetes | 47 | 25.41 | |

| Cancer | 16 | 8.65 | |

| Dependent >=1 ADL | 54 | 31.76 | |

| Dependent >=1 IADL | 120 | 70.59 | |

| Dementia severity at diagnosis: | |||

| Mild | 144 | 77.42 | |

| Moderate | 29 | 15.59 | |

| Severe | 12 | 6.45 |

Note: CHF= Congestive Heart Failure; ADL= Activities of Daily Living; IADL= Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

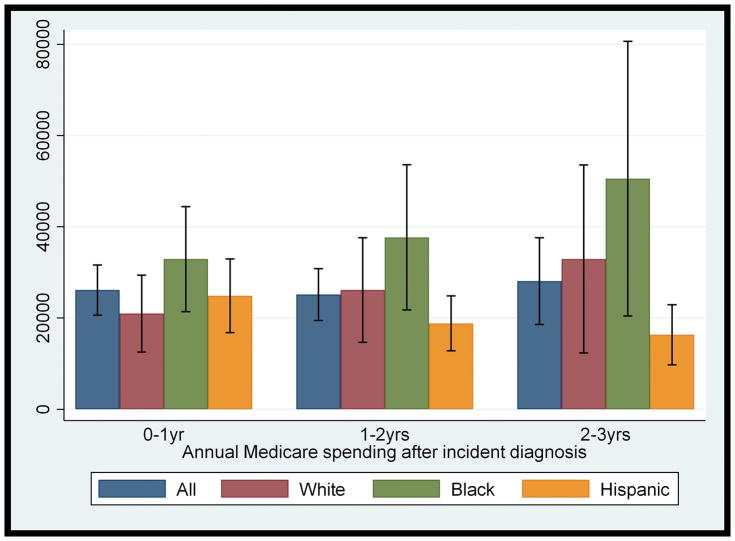

Hispanics were 4 years younger at diagnosis than Whites (83 vs. 87 years). Non-Hispanic Whites had the lowest levels of comorbidity at diagnosis (mean =1.57) and Hispanics had highest (mean =2.58)). There were no differences in disability at the time of diagnosis although non-Hispanic Whites were more likely to be diagnosed at later stages of illness (% diagnosed with severe dementia not reported by ethnicity due to sample size restrictions). (See Supplementary Table 2 for comparison of characteristics by ethnicity.) As shown in Figure 1, average spending was consistently higher for non-Hispanic Blacks relative to non-Hispanic Whites each year after diagnosis. After adjusting for dementia severity, age at diagnosis, level of education, comorbidity, total years of follow-up after diagnosis and whether the subject died during observation period, non-Hispanic Blacks had an 82% increased rate of spending one year after diagnosis although this did not meet statistical significance (p=.06). Hispanics were not significantly different from non-Hispanic Whites (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1.

Mean annual Medicare expenditures and 95% confidence intervals after dementia diagnosis by ethnicity

Decedent sample with incident dementia

Among individuals in the decedent sample, average age at death was 88.8. At their last evaluation, 16% of individuals had severe dementia and 61% were dependent in at least one ADL. (See Supplementary Table 4 for demographic and clinical characteristics.) Almost half were in the ICU at least once following their dementia diagnosis and more than one third underwent life-sustaining procedures after diagnosis including intubation/mechanical ventilation (27%). Only 21% received any hospice care.

The decedent sample survived on average for 3 years (Range 0–10 years) from incidence to death (median =2.4 years). Of note, Hispanics survived on average one year longer than non-Hispanic Blacks or Whites (Table 2). Total Medicare expenditure from incidence to death was an average of $152,352, or $69,370 per year. The vast majority of individuals were hospitalized following their dementia diagnosis with an average of 5.2 hospitalizations over the course of their illness. Non-Hispanic Blacks with dementia had the highest spending from time of diagnosis to death with a mean of $204,575 total expenditures from diagnosis to death, or $86,920 per year. They had almost twice as many hospital admissions as non-Hispanic Whites after dementia diagnosis (7.1 vs. 3.6; p<.05) and the least number of hospice days (mean=3.22) among ethnic groups.

Table 2.

Medicare Expenditures and healthcare utilization from dementia incidence to death by ethnicity (n=86)

| Total | non-Hispanic White (n=26) | non-Hispanic Black (n=23) | Hispanic (n=37) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Survival time, years, mean (SD) | 3.02(2.29) | 2.53(1.97) | 2.65(2.11) | 3.59(2.52) |

|

| ||||

| CHARACTERISTICS AT DEATH | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 88.84(6.77) | 90.27(7.42) | 88.67(6.92) | 87.93(6.20) |

|

| ||||

| Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 2.74(1.67) | 2.62(1.96) | 2.61(1.56) | 2.92(1.54) |

|

| ||||

| ADL difficulty index, mean (SD) | 1.21(1.18) | 1.46(1.22) | 1.14(1.17) | 1.09(1.16) |

|

| ||||

| IADL difficulty index, mean (SD) | 2.36(1.30) | 2.33(1.20) | 2.41(1.18) | 2.35(1.45) |

|

| ||||

| UTILIZATION | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hospital admissions, mean (SD) | 5.22 (5.55) | 3.58(4.53) | 7.09(6.92)** | 5.22(5.01) |

|

| ||||

| Hospital days, mean (SD) | 72.78 (88.45) | 61.00(78.71) | 104.43(95.33) ** | 61.38(87.98) |

|

| ||||

| ICU days, mean (SD) | 3.27 (6.05) | 2.73(4.80) | 4.35(6.34) | 2.97(6.70) |

|

| ||||

| Hospice days, mean (SD) | 18.78(75.83) | 28.81(101.17) | 3.22 (9.16) | 21.41(78.63) |

|

| ||||

| MEDICARE EXPENDITURES AFTER DEMENTIA DIAGNOSIS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Annual (2017$) | ||||

| mean (SD) | $69,370(80,120) | $79,949(122,772) | $86,920(59,583) | $54,541(45,546) |

| [median] | [$46,730] | [48,344] | [$86,069]* | [32,665] |

|

| ||||

| Total (2017$) | ||||

| mean (SD) | $152,352(153,770) | $117,928(124,661) | $204,575(198,892) | $144,078(134,887) |

| [median] | [$96,223] | [$74,168] | [$158,661]* | [$95,646] |

Note: ADL= Activities of Daily Living; IADL= Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; ICU= Intensive Care Unit;

p<.10 rank sum;

p<.05 rank sum

In models unadjusted for clinical characteristics or demographics, non-Hispanic Blacks with dementia had $86,647 higher Medicare expenditures than non-Hispanic Whites from incidence to death. This translates to a 74% higher rate of spending (p=.05). Hispanics, on the other hand, did not have significantly different total Medicare expenditures, or in any individual utilization categories, than non-Hispanic Whites after incidence, despite living on average one year longer with the disease. In adjusted cost comparisons non-Hispanic Blacks had a 41% increase in spending compared to non-Hispanic Whites from time of diagnosis to death translating into $57,606 additional Medicare expenditures (p=.15) (Table 3). (See Supplementary Table 5 for full model coefficients.) These findings were largely driven in the first year after diagnosis in with non-Hispanic Blacks had more than two-fold increased rate of spending compared to Whites (p=.03) in adjusted models.

Table 3.

Total Medicare spending from time of dementia onset until death by ethnicity (n=86)

| non-Hispanic Black (n=23) | Hispanic (n=37) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Total | Difference in mean expenditures relative to non-Hispanic Whites (2017$) | $86,647 | $26,149 |

|

| |||

| Unadjusted model | |||

| Rate ratio | 1.74 | 1.23 | |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.44 | |

|

| |||

| Adjusted model | |||

| Average marginal effects (2017$) | $57,606 | $-15,326 | |

|

| |||

| Rate ratio | 1.41 | .90 | |

| p-value | 0.15 | 0.68 | |

|

| |||

| Annual | |||

| Year 1 | Average marginal effects (2017$) | $30,361 | $-12,341 |

| Rate ratio | 2.28 | 1.60 | |

| p-value | 0.03 | 0.27 | |

|

| |||

| Year 2 | Average marginal effects (2017$) | $32,663 | $-54,734 |

| Rate ratio | 1.70 | 0.65 | |

| p-value | 0.21 | 0.36 | |

|

| |||

| Year 3 | Average marginal effects (2017$) | $10,599 | $-74,182 |

| Rate ratio | 1.20 | 0.75 | |

| p-value | 0.75 | 0.55 | |

Note: white as referent category; GLM models with log link and gamma distributions

Adjusted for nursing home status at death, disease severity at death (mild vs. moderate or severe) gender, age at death, years of education, modified Charlson comorbidity index at time of death and time from incident dementia diagnosis to death

DISCUSSION

This study is the first of its kind to estimate total Medicare expenditures and utilization from the time of diagnosis until death in a multi-ethnic community based cohort. Our work confirms previous research2,31 suggesting that care for individuals with dementia including the EOL period is costly and includes high-intensity and complex care. In our sample, patients had frequent ICU stays and repeat hospitalizations after diagnosis. Not surprisingly, given the documented underuse of hospice and palliative care among individuals with dementia, and among ethnic minorities,32 only 21% of our sample received any hospice care. Furthermore, our research suggests that care for non-Hispanic Blacks with dementia is most costly, including more high intensity treatments and less hospice use. We were unable to detect any significant differences in Hispanics’ Medicare expenditures compared to non-Hispanic Whites, despite longer survival after diagnosis. Our findings regarding overall expenditures and ethnic differences are noteworthy in light of concerns over high costs of dementia in society.33

Importantly, our assessment of dementia was based on a clinical determination of dementia and not limited to claims-based diagnoses. Thus we are able to avoid biases such as under-recognition or under-coding of dementia, or other measurement limitations that are inherent to studies based on administrative claims only.34 In post-hoc analysis we found that 25% of incident cases in the sample had no diagnosis of dementia in claims data at any point in follow-up. Fourteen percent had a first diagnosis of dementia in their claims more than one year after clinical assessments.

While our study examines ethnic differences in healthcare utilization from dementia diagnosis to death, our findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence suggesting that Blacks receive more aggressive care and have higher EOL spending than Whites.15–17 The reasons may include preferences for more aggressive care, mistrust of the healthcare system, lack of in-home resources and miscommunication and misunderstanding of treatment options and hospice benefits.35 Many of these issues may be magnified in the context of advanced dementia. Given the substantial negative consequences of hospitalization and other aggressive care for patients with dementia6 including subsequent cognitive decline and increased risk of functional decline or iatrogenic complications, we need to institute more conservative care for patients with dementia who have poor prognoses, when appropriate. Barriers to excellent EOL care for dementia are widespread including lack of financial incentives for palliative care in nursing homes, lack of understanding of dementia as a terminal illness, complexity of symptom assessment and management, and lack of advance directives for those without decision-making capacity.36 Moreover, we need to continue to study why ethnic/racial variation exists in these care patterns.

Additionally, this study was conducted in a community with a large aging Hispanic population, a group who is often understudied in research on dementia. This population is expected to expand significantly-- a 2016 report estimated the number of US Hispanics with Alzheimer’s disease would increase from 379,000 in 2012 to 3.5 million by 2060. 21 Cost research is especially critical in this population as Hispanics are more likely to live in poverty than non-Hispanic populations. Although Hispanics were diagnosed with dementia at younger ages and had longer follow up periods after diagnosis as shown in other community-based samples,37,38 their total costs from diagnosis to death are lower than non-Hispanic Blacks and are not significantly different than non-Hispanic Whites. This may be due in part to the extensive role played by families in the care of Hispanic patients with dementia.39,40 Given that substantial disparities in healthcare access by ethnicity and socioeconomic status have been documented, 41 further study to replicate these findings and better understand the reasons for these differences is imperative.

There are a number of limitations. First, the small sample precluded detection of differences across specific utilization measures (e.g., hospice) and limited our ability to detect more subtle differences across groups. Larger cohort studies comparing expenditures by ethnicity in populations with dementia using clinical diagnoses of dementia are necessary. Furthermore, our primary outcome, total Medicare expenditures, does not account for all healthcare costs that decedents and their families incur. Medicare provides nearly universal health care coverage for U.S. adults older than 65 years. However, it does not cover many health-related expenses essential to those with chronic diseases or life-limiting illnesses, such as home care services, equipment, and non-rehabilitative nursing home care. Out-of-pocket costs including costs of informal caregiving were also not included in this analysis and are substantial at the EOL.4 Furthermore, our analyses did not account for Medicare Part D costs for prescription drugs nor did we include Medicaid costs.

The sample was also limited to Medicare expenditures of FFS Medicare beneficiaries and only one geographic region in Manhattan, which may be unique in its spending patterns. While this reduces generalizability of findings and may account for different spending patterns than previously reported in national samples,2,42 it likely controls for bias related to variability in regional care practices that are known to impact treatment intensity. Also, the majority of Hispanics in this sample are from the Dominican Republic, thus limiting generalizability to national sample of Hispanics. Of note, our analyses focus on deaths that occurred before 2010. Practice patterns have changed over time, favoring increases in hospice use although increasing use of ICU.43 Our data do not contain information about patient or family preferences or advance directives. Differences in the aggressiveness of care in some instances may be the result of patients’ own wishes. It is also likely that some of the differences in care may be appropriate based on patient needs. Although these factors have been included in larger studies, they have been found to attenuate association not fully explain it.17 While we assess dementia at regular intervals there are time gaps. Average time from last evaluation of dementia status to death was 1.6 years. Hence, we may be underestimating dementia severity at time of death.

Despite these limitations, our work provides important insight regarding the cost of dementia from incidence to death and highlights the need to consider racial/ethnic differences in healthcare spending in this population. This variation may in part be attributable to lack of effective and informed communication and may raise important concerns regarding informed and shared decision-making about EOL care in advanced dementia. Future work must continue to explore racial/ethnic differences in treatment patterns from diagnosis throughout the EOL period including interactions with the healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG07370, AG037212). Dr. Ornstein was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K01AG047923). Dr. Zhu is also supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration.

Footnotes

Conflicts: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. All authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bynum JP. The long reach of Alzheimer’s disease: patients, practice, and policy. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2014 Apr;33(4):534–540. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Annals of internal medicine. 2015 Nov 17;163(10):729–736. doi: 10.7326/M15-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Apr 4;368(14):1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Fahle S, Marshall SM, Du Q, Skinner JS. Out-of-Pocket Spending in the Last Five Years of Life. Journal of general internal medicine. 2012 Sep 5; doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perrar KM, Schmidt H, Eisenmann Y, Cremer B, Voltz R. Needs of people with severe dementia at the end-of-life: a systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2015;43(2):397–413. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Oct 15;361(16):1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell SL, Morris JN, Park PS, Fries BE. Terminal care for persons with advanced dementia in the nursing home and home care settings. J Palliat Med. 2004 Dec;7(6):808–816. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012 Jan 11;307(2):165–172. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein K, Gu Y, Andrews H, Stern Y. Use and cost of hospitalization in dementia: longitudinal results from a community-based study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2015 Aug;30(8):833–841. doi: 10.1002/gps.4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein K, et al. Medicare Utilization and Expenditures Around Incident Dementia in a Multiethnic Cohort. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2015 Nov;70(11):1448–1453. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Z, Coots LA, Kaganova Y, Wiener JM. Hospital and ED use among Medicare beneficiaries with dementia varies by setting and proximity to death. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2014 Apr;33(4):683–690. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein KA, Gu Y, Andrews H, Stern Y. Interactive Effects of Dementia Severity and Comorbidities on Medicare Expenditures. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2017;57(1):305–315. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith LE, Gruneir A, Fisher K, et al. Patterns of health service use in community living older adults with dementia and comorbid conditions: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMC geriatrics. 2016 Oct 26;16(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0351-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amjad H, Carmichael D, Austin AM, Chang CH, Bynum JP. Continuity of Care and Health Care Utilization in Older Adults With Dementia in Fee-for-Service Medicare. JAMA internal medicine. 2016 Sep 01;176(9):1371–1378. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Annals of internal medicine. 2011 Feb 15;154(4):235–242. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnato AE, Berhane Z, Weissfeld LA, Chang CC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC. Racial variation in end-of-life intensive care use: a race or hospital effect? Health Serv Res. 2006 Dec;41(6):2219–2237. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byhoff E, Harris JA, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Racial and Ethnic Differences in End-of-Life Medicare Expenditures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016 Sep;64(9):1789–1797. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population. Medical care. 2007 May;45(5):386–393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, Lynn J. Medicare beneficiaries’ costs of care in the last year of life. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2001 Jul-Aug;20(4):188–195. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shugarman LR, Campbell DE, Bird CE, Gabel J, TAL, Lynn J. Differences in Medicare expenditures during the last 3 years of life. Journal of general internal medicine. 2004 Feb;19(2):127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu S, Vega WA, Resendez J, Jin H. Latinos & ALzheimer’s Disease: New numbers behind the crisis. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, et al. The APOE-epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1998 Mar 11;279(10):751–755. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984 Jul;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern Y, Andrews H, Pittman J, et al. Diagnosis of dementia in a heterogeneous population. Development of a neuropsychological paradigm-based diagnosis of dementia and quantified correction for the effects of education. Archives of neurology. 1992 May;49(5):453–460. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530290035009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Associatio; 1987. Revised ed. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993 Nov;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tschirhart ECDQ, Kelley AS. Factors influencing the use of intensive procedures in the last 6 months of life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jgs.13104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang CC, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC. Development and validation of hospital “end-of-life” treatment intensity measures. Medical care. 2009 Oct;47(10):1098–1105. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181993191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, Marinopoulos SS, Briggs WM, Hollenberg JP. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2008 Dec;61(12):1234–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114(512):797–811. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.512.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, Canavan M, Cherlin E, Bradley E. End-of-Life Care Transition Patterns of Medicare Beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Jul;65(7):1406–1413. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erel M, Marcus EL, Dekeyser-Ganz F. Barriers to palliative care for advanced dementia: a scoping review. Annals of palliative medicine. 2017 Oct;6(4):365–379. doi: 10.21037/apm.2017.06.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prigerson HG. Costs to society of family caregiving for patients with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2003 Nov 13;349(20):1891–1892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor DH, Jr, Ostbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL. The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: the case of dementia revisited. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2009;17(4):807–815. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LoPresti MA, Dement F, Gold HT. End-of-Life Care for People With Cancer From Ethnic Minority Groups: A Systematic Review. The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2016 Apr;33(3):291–305. doi: 10.1177/1049909114565658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. Journal of general internal medicine. 2004 Oct;19(10):1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitten LJ, Ortiz F, Fairbanks L, et al. Younger age of dementia diagnosis in a Hispanic population in southern California. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2014 Jun;29(6):586–593. doi: 10.1002/gps.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Johnson JK, Perez-Stable EJ, Whitmer RA. Survival after dementia diagnosis in five racial/ethnic groups. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2017 Feb 05; doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luchsinger JA, Tipiani D, Torres-Patino G, et al. Characteristics and mental health of Hispanic dementia caregivers in New York City. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2015 Sep;30(6):584–590. doi: 10.1177/1533317514568340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Llanque SM, Enriquez M. Interventions for Hispanic caregivers of patients with dementia: a review of the literature. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2012 Feb;27(1):23–32. doi: 10.1177/1533317512439794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jutkowitz E, Kane RL, Gaugler JE, MacLehose RF, Dowd B, Kuntz KM. Societal and Family Lifetime Cost of Dementia: Implications for Policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Oct;65(10):2169–2175. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013 Feb 6;309(5):470–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.207624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.