Abstract

Aims/Introduction

To explore the association between lactation and type 2 diabetes incidence in women with prior gestational diabetes.

Materials and Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library for cohort studies published through 12 June 2017 that evaluated the effect of lactation on the development of type 2 diabetes in women with prior gestational diabetes. A random effects model was used to estimate relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

A total of 13 cohort studies were included in the meta‐analysis. The pooled result suggested that compared with no lactation, lactation was significantly associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.48–0.90, I 2 = 72.8%, P < 0.001). This relationship was prominent in a study carried out in the USA (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.43–0.99), regardless of study design (prospective design RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.41–0.76; retrospective design RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.40–0.99), smaller sample size (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.30–0.92, P = 0.024) and follow‐up duration >1 years (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.56–1.00), and the study used adjusted data (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.94). Finally, by pooling data from three studies, we failed to show that compared with no lactation, long‐term lactation (>1 to 3 months postpartum) was associated with the type 2 diabetes risk (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.41–1.17).

Conclusions

The present meta‐analysis showed that lactation was associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes in women with prior gestational diabetes. Furthermore, no significant relationship between long‐term lactation and type 2 diabetes risk was detected. The impact of long‐term lactation and the risk of type 2 diabetes should be verified in further large‐scale studies.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes mellitus, Lactation, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common pregnancy‐related complication1. GDM is diabetes that is first diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not clearly either pre‐existing type 1 or type 2 diabetes2. GDM occurs annually in 3–5% of all pregnant women in the USA3. GDM is associated with substantial rates of adverse maternal outcomes. These outcomes include increases in pre‐eclampsia, gestational hypertension and cesarean section in the mother, as well as increases in macrosomia, birth injury, respiratory distress syndrome and hyperbilirubinemia in the infant4, 5, 6.

Soon after delivery, glucose hemostasis returns to non‐pregnancy levels. However, women affected by GDM remain at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus in the future7. A meta‐analysis of 20 cohort studies found that GDM significantly predisposed women to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus3. There was an almost linear increase in the cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus during the first 10 years post‐delivery8. Several risk factors contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in patients with prior GDM, including body mass index, family history of diabetes, non‐white ethnicity, advanced maternal age, multiparity, hypertension and preterm delivery7, 9.

It has been suggested that breast‐feeding might have protective effects against the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus10. The importance of breast‐feeding has long been recognized for mothers and their children, irrespective of their geographical location or economic status11. Breast‐feeding has various health benefits12–it might protect children from infectious diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and positively impact their intelligence. In mothers, lactation is associated with a reduced risk of obesity and breast cancer11, 13.

However, mothers with GDM are less likely to partly or exclusively breast‐feed14. Lactation for mothers with GDM is often delayed as a result of pregnancy‐related complications and increased neonatal morbidity14. Even if mothers with GDM do initiate breast‐feeding, lactation typically lasts a shorter duration than in women without GDM15. It remains unclear whether lactation in mothers with GDM could affect the progression of future type 2 diabetes mellitus risk. Current evidence suggests conflicting results. Several studies have advocated breast‐feeding10, 16, whereas others have failed to show the positive role of lactation17, 18. Furthermore, the duration and intensity of lactation varied among previous studies. Therefore, we carried out the present systematic review and meta‐analysis to investigate the association between lactation and development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with prior GDM.

Methods

All analyses were based on previous published studies, therefore, ethical approval and patient consent were not required.

Data sources, search strategy and study selection

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines when carrying out this meta‐analysis19. We carried out a systematic literature search of studies published in the English language that investigated the association between lactation and type 2 diabetes mellitus in GDM patients. The literature was searched in the PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library databases from inception to 12 June 2017. We used the following keywords and medical terms: (‘lactation’ OR ‘breastfeeding’ OR ‘breast‐feeding’) AND (‘gestational’ OR ‘maternal’ OR ‘pregnant’ OR ‘pregnancy’) AND (‘glucose intolerance’ OR ‘type 2 diabetes mellitus’ OR ‘hyperglycemia’). We also manually searched the bibliographies of key articles in this field and those cited by critical reviews.

Two authors (Lijun Feng and Qunli Xu) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the search results, and selected studies of relevant topics. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third author (Hongying Pan). We included studies that fulfilled the following criteria: (i) prospective or retrospective cohort studies on women with prior GDM; (ii) exploration of the association between lactation and the outcomes of type 2 diabetes mellitus; and (iii) studies in which participants developed type 2 diabetes mellitus at least 6 weeks after delivery; in these cases, type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis was established based on the results of an oral glucose tolerance test or fasting plasma glucose concentration.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors independently reviewed eligible studies and extracted the following information for a standardized electronic data form: author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, mean or median age, incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, diagnostic criteria of GDM and type 2 diabetes mellitus, studied population, lactation duration, comparison groups, stratified subgroups, comparisons, and follow‐up duration. The quality of included studies was appraised using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies20. This scale included three items: (i) selection of study group; (ii) comparability of study groups; and (iii) ascertainment of the outcome of interest. A star rating of 0–9 was allocated to each study based on these aspects. We assigned scores of 0–3, 4–6 and 7–9 for low‐, moderate‐ and high‐quality of studies, respectively. The data extraction and quality assessment were carried out independently by two authors. Information was examined and adjudicated independently by an additional author referring to the original studies.

Statistical analysis

We examined the relationship between lactation and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus on the basis of the effect estimate and its 95% confidence interval (CI) published in each study. Relative risks (RRs) were expressed with its 95% CIs and were either extracted directly or calculated indirectly21, 22. Heterogeneity between studies was investigated by using the Q statistic, and we considered P‐values <0.10 as indicative of significant heterogeneity23, 24. Meta‐regression analysis was carried out to determine whether study‐level covariates potentially accounted for the heterogeneity. The influence of individual studies was also investigated using the leave‐one‐out cross‐validation method to test the robustness of the primary outcomes25. Subgroup analyses were carried out based on the following variables: study setting (USA or non‐USA), study size (<500 participants or ≥500 participants), study design (prospective or retrospective), follow‐up duration (<1 years vs ≥1 year), adjusted (adjusted RR vs non‐adjusted RR) and calculated (calculated RR vs extracted RR). Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot. We also used the Egger26 and Begg's27 tests to examine funnel plot asymmetry. Statistical significance was based on a P‐value <0.05 in all analyses. Statistical analyses were carried out using STATA software (version 10.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and R software (version 3.3.3; Lucent Technologies, Murray Hill, NJ, USA).

Results

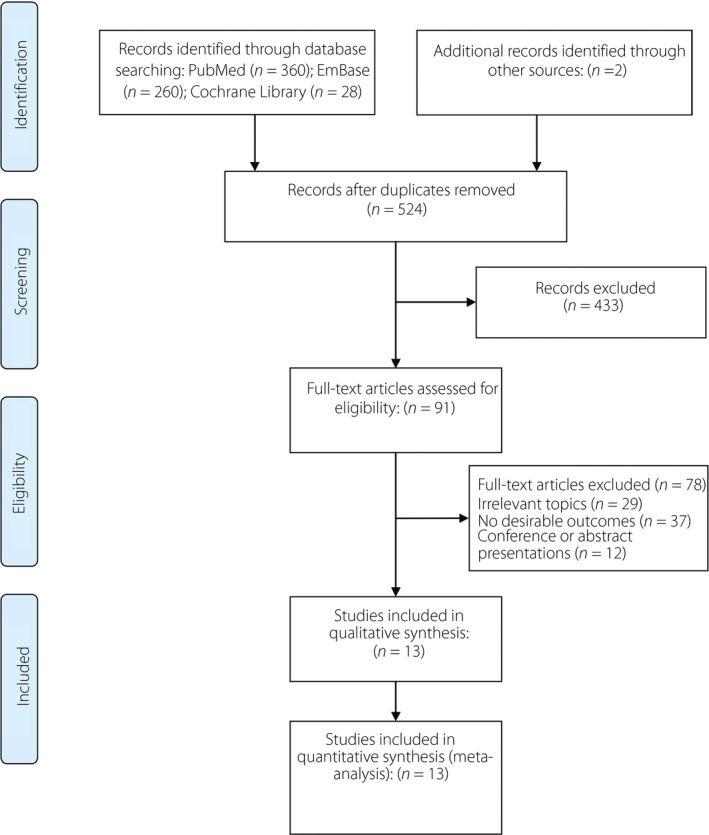

The search strategy yielded 648 records, including 360 studies from PubMed, 260 from Embase and 28 from the Cochrane Library database. After excluding 124 duplicates, 524 studies were assessed for eligibility. Furthermore, an additional two records were identified, but the data from these abstracts were not used for analysis28, 29. We further excluded irrelevant studies and those without sufficient data; 13 studies were included in the meta‐analysis10, 16, 17, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39. A flow diagram of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Six studies were prospective cohort studies, and seven were retrospective cohort studies. Six studies were carried out in the USA, and the rest in Ireland, Korea, Germany, Belgium and Australia. Sample sizes ranged from 91 to 116,671 participants. The average maternal age of women with GDM was approximately 30 years in most studies. The diagnostic criteria for GDM included National Diabetes Data Group, American Diabetes Association, World Health Organization, third GDM workshop conference, Carpenter–Coustan Criteria and countrywide criteria. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was diagnosed according to the American Diabetes Association, National Diabetes Data Group, World Health Organization or countrywide guidelines3. The duration of lactation was only considered in four studies. The follow‐up period varied from approximately 3 months to >10 years. The average score was 6.7, and the score for each study was ≥5, suggesting that all the studies were of moderate or high quality (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the study selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author (year) | Region | Design | No. patients | Age (years) | T2DM occurrence | GDM criteria | T2DM or IGT criteria | Population showing data | Lactation duration | Subgroups | Comparison | Follow‐up duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kjos et al. (1993)30 | USA | Prospective cohort | 809 | 31 | Event rate: 7% | NDDG | NDDG | GDM | 4–12 weeks | Insulin therapy | BF vs no BF | 3 months |

| Kjos et al. (1998)17 | USA | Retrospective cohort | 904 | 30 | Event rate: 19% | NDDG | NDDG | GDM women using non‐hormonal contraception | NA | None | BF vs no BF | 7.5 years |

| Buchanan et al. (1998)31 | USA | Prospective cohort | 91 | 30 | Event rate: 15% | Third GDM workshop conference | WHO | T2DM not within 6 months postpartum | NA | None | BF vs no BF | 11–26 months |

| Stuebe et al. (2005)16 | USA | Retrospective cohort | 116,671 | 35 | IR: 6.24 per 1000 person‐years | Questionnaire | NDDG | GDM | NA | BF duration | BF vs no BF | 12 years |

| Nelson et al. (2008)32 | USA | Retrospective cohort | 572 | 32 | Event rate: 14% | Medical record | ADA | GDM followed at 1 year | NA | None | BF vs no BF | 1 year |

| Kim et al. (2011)33 | Korea | Prospective cohort | 381 | 34 | Event rate: 5.2% | Carpenter–Coustan | ADA | GDM | ≈2 months | None | BF vs no BF | 6–12 weeks |

| O'Reilly et al. (2011)34 | Ireland | Retrospective cohort | 564 | 33 | Event rate: 3% | WHO or IADPSG | ADA | GDM | NA | Europeans | BF vs no BF | 3 months |

| Ziegler et al. (2012)10 | Germany | Prospective cohort | 304 | Median: 31 | CR: 63.6% (95% CI 55.8–71.4) | Germany Diabetes Association | ADA | IAA (–) GDM (89.5%) | IAA (–) Median: 9 weeks | GDM treatment, BMI | BF >3 months vs. BF ≤3 months or no BF | 19 years |

| Capula et al. (2014)35 | Italian | Retrospective cohort | 454 | Median: 35 | Event rate: 4% | Carpenter–Coustan or IADPSG | ADA | GDM | NA | None | BF vs no BF | 6–12 weeks |

| Gunderson et al. (2015)36 | USA | Prospective cohort | 1035 | Mean: 33 | IR: 5.64 (95% CI 4.60–6.68) per 1000 person‐months | ADA | ADA | GDM | 80% >2 months | BF duration, BF intensity | BF > 2 months vs BF ≤2 months; BF vs no BF | Median: 1.8 years |

| Moon et al. (2015)37 | Korea | Prospective cohort | 418 | 32 | Event rate: 12.7% | Third GDM workshop conference | ADA | GDM | NA | None | BF vs no BF | Median: 4 years |

| Chamberlain et al. (2016)38 | Australia | Retrospective cohort | 483 | NA | CR: 18.3% (12.6–26.3%) for indigenous; CR: 6.4% (3.4–11.7%) for non‐indigenous | Australian Diabetes (pregnancy guidelines) | Australian guidelines | GDM | NA | Indigenous Australians | Fully BF vs partial BF vs no BF | 7 years |

| Benhalima (2016)39 | Belgium | Retrospective cohort | 191 | 32 | Event rate: 5.9% | WHO | ADA | GDM | NA | None | BF vs no BF | 12 weeks |

ADA, American Diabetes Association; BMI, body mass index; BF, breast‐feeding; CR, cumulative risk; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IAA, islet autoantibody; IADPSG, International Association of Diabetic Pregnancy Study Group; ICA, islet cell antibody; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; IR, incidence rate; NDDG, National Diabetes Data Group; NA, not available; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; USA, the United States of America; WHO, World Health Organization.

Effect of lactation versus no lactation on the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus

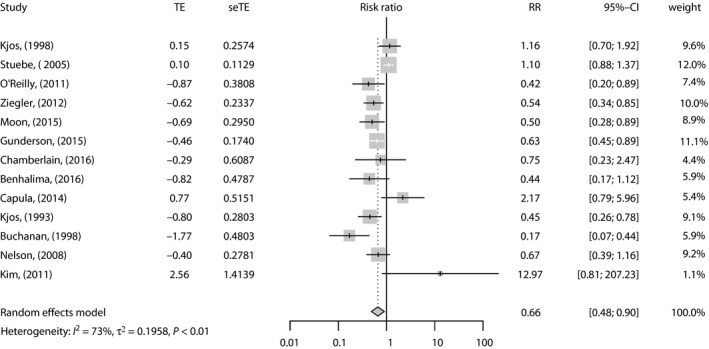

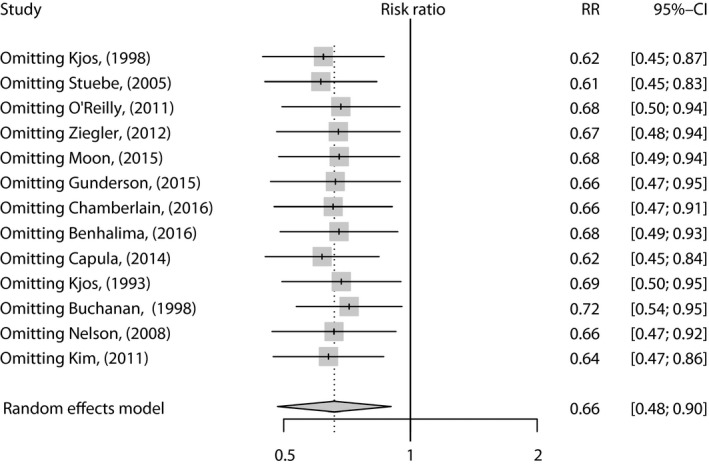

Nine studies showed a correlation between lactation and type 2 diabetes mellitus development. Capula et al.35 showed crude data for RR, whereas other studies reported four‐layer table data to calculate RR. The study authored by Stuebe et al.16 included five subgroups of participants with different lactation duration. Gunderson et al.36 presented three subgroups of participants with different lactation intensities. The data from these subgroups were pooled using the fixed‐effects model in each study. Ziegler et al.10 focused on breast‐feeding for >3 months and compared it with insufficient breast‐feeding (no lactation or breastfeeding for ≤3 months). Chamberlain et al.38 compared the effects of exclusive lactation with no lactation. The pooled data showed that compared with no lactation, lactation was associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with prior GDM (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.48–0.90; Figure 2). A large amount of heterogeneity was revealed (I 2 = 72.8%, P < 0.001). In sensitivity analysis, the overall effect was a non‐significant change with mutual exclusion of the studies (Figure 3). The heterogeneity could be decreased by omitting Stuebe et al.16 in the new analysis (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.45–0.83, I 2 = 60.2%; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of studies showing the relative risk (RR) for the association between lactation and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk. CI, confidence interval; seTE, standard error of the log risk ratio; TE, transformation of relative risk.

Figure 3.

The finding of sensitivity analysis. CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

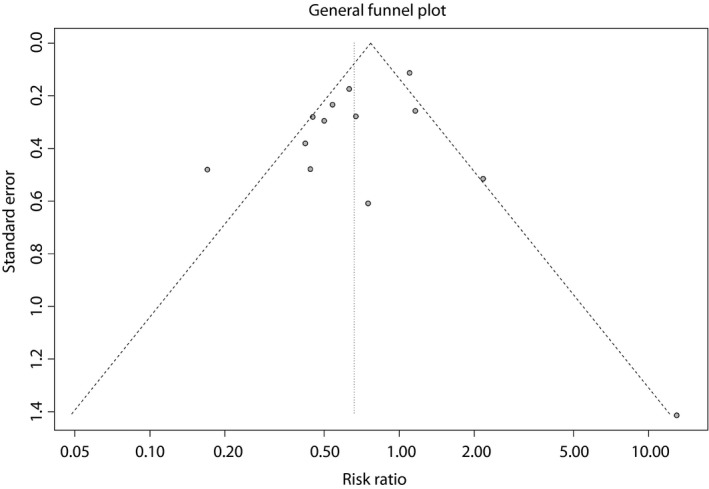

To investigate the effects of various study characteristics on the pooled RR, subgroup analysis and meta‐regression were carried out by subgroups. In subgroup analyses, the overall effect was non‐significant for studies that were not carried out in the USA (P = 0.085), had a sample size >500 (P = 0.122), had a follow‐up duration <1 year (P = 0.154), data were not adjusted (P = 0.416) or regardless of calculated RR (Table 2). No statistical significances were identified in the overall effects for various subgroups by univariate and multivariate meta‐regression analyses. Detailed data are shown in Table 2. The funnel plot was symmetrical (Figure 4). No publication bias was shown by the Egger's test (P = 0.320) or the Begg's test (P = 1.000).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis and meta‐regression for studies showing the association between lactation and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk in women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus

| Subgroups | n | RR (95% CI) | P‐value | I 2 (P‐value) | P for subgroup | Meta‐regression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| Total | 13 | 0.66 (0.48–0.90) | 0.008 | 72.8% (<0.001) | |||

| Region | 0.971 | 0.930 | 0.828 | ||||

| USA | 6 | 0.66 (0.43–0.99) | 0.047 | 81.3% (<0.001) | |||

| Non‐USA | 7 | 0.66 (0.42–1.06) | 0.085 | 53.7% (0.04) | |||

| Design | 0.389 | 0.579 | 0.144 | ||||

| Prospective | 5 | 0.56 (0.41‐0.76) | <0.001 | 35.2% (0.187) | |||

| Retrospective | 8 | 0.63 (0.40‐0.99) | 0.044 | 73.6% (<0.001) | |||

| Sample size | 0.279 | 0.327 | 0.408 | ||||

| <500 | 6 | 0.52 (0.30–0.92) | 0.024 | 58.1% (0.036) | |||

| ≥500 | 7 | 0.75 (0.53–1.08) | 0.122 | 76.2% (<0.001) | |||

| Follow up | 0.546 | 0.392 | 0.197 | ||||

| <1 year | 6 | 0.59 (0.28–1.22) | 0.154 | 73.5% (0.002) | |||

| ≥1 year | 7 | 0.75 (0.56–1.00) | 0.050 | 65.5% (0.008) | |||

| Adjusted | 0.949 | 0.895 | 0.155 | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 0.69 (0.50–0.94) | 0.018 | 67.7% (0.003) | |||

| No | 5 | 0.71 (0.31–1.63) | 0.416 | 79.0% (0.001) | |||

| Calculate RR | 0.413 | 0.321 | 0.196 | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 051 (0.22–1.16) | 0.108 | 74.1% (0.009) | |||

| No | 9 | 0.74 (0.54–1.01) | 0.057 | 68.3% (0.001) | |||

CI, confidence interval; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; RR, relative risk; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of included studies.

Effect of long‐term lactation versus no lactation on the outcome of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Just three studies specifically investigated the impacts of lactation duration10, 16, 36. Stuebe et al.16 compared lactation lasting 3 months with formula feeding. Gunderson et al.36 compared lactation lasting 3 months with breast‐feeding lasting <3 months. Ziegler et al.10 compared lactation lasting 3 months with breast‐feeding lasting <3 months or formula feeding. The pooled data showed that compared with no lactation, long‐term lactation (>1–3 months postpartum) was not associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.41–1.17, I 2 = 84.4%, P < 0.050). However, when excluding the study by Stuebe et al., the pooled result became significant (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.40–0.72, I 2 = 0, P = 0.950).

Discussion

In the present meta‐analysis, a significant correlation between lactation and the reduction of type 2 diabetes mellitus risk was detected (RR 0.66, P = 0.008), this association was stable in sensitivity analysis. The exclusion of 13 studies, one‐by‐one, unanimously, resulted in an overall marginally significant result. By pooling six prospective studies, the impact of lactation was markedly significant (RR 0.56; 95% CI 0.41–0.76). Furthermore, the impact of lactation remained significant for multiple subgroups. No publication bias was detected in our analyses. We failed to identify a significant protective role of long‐term lactation on type 2 diabetes mellitus risk (OR 0.69, P = 0.170). However, the result was limited, as just three studies were included.

The mechanism underlying the preventive role of lactation against type 2 diabetes mellitus remains unclear. Lactation has high energy demands, which might lead to alterations in the metabolic process, including changes in glucose metabolism, increased lipolysis and increased energy expenditure40. A series of experimental studies showed that lactation might increase insulin sensitivity and lower insulin levels41, 42. A previous study carried out in a rat model showed a 12‐fold increase in insulin uptake by the mammary glands of lactating rats, as well as a significant decrease in the half‐life of insulin in the plasma43. Lactating women have physiologically elevated prolactin, which is positively correlated with lower mean fasting glucose and insulin levels 8 weeks after delivery44. Current research evidence calls for exclusive breast‐feeding during the first 6 months of an infant's life11. Lactation has multiple benefits, including protective effects against gynecological cancers in mothers, and infection and obesity in children11. As for diabetic outcomes, aside from our finding that lactation prevents subsequent type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with prior GDM, breast‐feeding might also help reduce the risk of future type 2 diabetes mellitus in children45. Breastfeeding is a convenient and low‐cost method of improving postpartum health. However, many studies that analyzed the risk factors for progression of GDM to type 2 diabetes mellitus overlooked the mother's lactation status46, 47, 48, 49. Mothers with prior GDM were less likely to breast‐feed their children than mothers without diabetes14. Lactation might be more difficult to initiate for these mothers because of neonatal morbidity and concerns regarding fluctuating blood glucose concentrations50. Notably, several studies have proven that racial, educational and socioeconomic status were important predictors of lactation initiation among women with GDM51, 52.

Several relevant systematic reviews or meta‐analyses exploring the association between breast‐feeding and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in mothers have already been published. Taylor et al.53 systematically reviewed the evidence about the association between breast‐feeding and maternal type 2 diabetes mellitus, published before 2005. No data analysis was carried out. Rayanagoudar et al.9 recently summarized and analyzed the risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus progression in women with GDM. They analyzed data from four studies and showed no association between lactation and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk. The role of lactation was only briefly mentioned among various other factors and was not explored in depth. The authors also acknowledged that their result might be imprecise, owing to the small number of studies and individuals9. Very recently, a meta‐analysis by Tanase‐Nakao et al.54 was published. A total of 14 reports of nine research groups were included in the qualitative synthesis–the authors concluded that lactation lasting >4–12 weeks postpartum is associated with a reduction in the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus compared with shorter lactation. Exclusive lactation lasting >6–9 weeks postpartum was also associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus compared with exclusive formula feeding. Breast‐feeding practices were reported to be influenced by multiple factors, such as obesity55. In comparison, the present meta‐analysis was primarily focused on exploring the association between lactation and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and included the most comprehensive relevant studies. Adjusted data were analyzed, with heterogeneity evaluated using subgroup, sensitivity and meta‐regression analyses.

The study had several limitations. The risk of bias assessment was carried out using the NOS. However, according to the recommendations from the study by Lo et al.56, we contacted the authors for information not published in the studies when applying the NOS in systematic reviews. However, only one of the authors responded, consequently, NOS assessment could not be carried out. The present findings are limited by the small number of included studies and the presence of significant heterogeneity. Several studies were retrospective case series, which might cause recall or selection bias. Furthermore, several studies did not discriminate total lactation from mixed lactation–formula feeding, which might weaken the association between lactation and diabetes risk. Although a significant association was shown when analyzing adjusted data, it is possible that residual confounding by factors not included in the adjusted model still occurred. Many studies did not show the important confounders for overall analysis, these potential confounders include medication and lifestyle factors that might accompany breast‐feeding, such as insulin therapy during pregnancy, contraception prescription after delivery, dietary habits and physical activity. The results of stratified analyses based on these factors were not provided, which restricted us from carrying out more detailed analysis to explore the source of heterogeneity. The discrepancy between crude and adjusted data reflected the crucial role of confounding factors. Notably, the diagnostic criteria varied among different regions. However, most criteria used the oral glucose tolerance test as the main screening test. The follow‐up duration varied between included studies, and several studies only followed patients for a few months. The duration of lactation also varied greatly between included studies. No sufficient data were available to show the dose–response curve between lactation duration and type 2 diabetes mellitus risk.

In conclusion, based on the present systematic review and meta‐analysis, lactation might protect against the future risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with prior GDM. Future studies are warranted to explain the mechanism behind the association between lactation and maternal glucose metabolism. More prospective cohort studies are also required to determine the causality.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1 | Newcastle–Ottawa scale for quality assessment of included studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Public Technology Research and Social Development Project, the Science Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2016ZDA011), and Scientific Research Project, Education of Zhejiang Province (ZC200805852).

J Diabetes Investig. 2018

References

- 1. Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Page KA. Gestational diabetes mellitus: risks and management during and after pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012; 8: 639–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes . Diabetes Care 2017; 40(Supplement 1): S11–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, et al Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet 2009; 373: 1773–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kitzmiller JL, Block JM, Brown FM, et al Managing preexisting diabetes for pregnancy: summary of evidence and consensus recommendations for care. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 1060–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baptiste‐Roberts K, Barone BB, Gary TL, et al Risk factors for type 2 diabetes among women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review. Am J Med 2009; 122: e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Casey BM, Lucas MJ, McIntire DD, et al Pregnancy outcomes in women with gestational diabetes compared with the general obstetric population. Obstet Gynecol 1997; 90: 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 1862–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop‐Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007; 30(Suppl 2): S251–S260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rayanagoudar G, Hashi AA, Zamora J, et al Quantification of the type 2 diabetes risk in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 95,750 women. Diabetologia 2016; 59: 1403–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ziegler AG, Wallner M, Kaiser I, et al Long‐term protective effect of lactation on the development of type 2 diabetes in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2012; 61: 3167–3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016; 387: 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Binns C, Lee M, Low WY. The long‐term public health benefits of breastfeeding. Asia Pac J Public Health 2016; 28: 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, et al Does breastfeeding influence risk of type 2 diabetes in later life? A quantitative analysis of published evidence. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 1043–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sparud‐Lundin C, Wennergren M, Elfvin A, et al Breastfeeding in women with type 1 diabetes: exploration of predictive factors. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 296–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hummel S, Winkler C, Schoen S, et al Breastfeeding habits in families with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2007; 24: 671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stuebe AM, Rich‐Edwards JW, Willett WC, et al Duration of lactation and incidence of type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2005; 294: 2601–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kjos SL, Peters RK, Xiang A, et al Contraception and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Latina women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA 1998; 280: 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Kjos SL, et al Antepartum predictors of the development of type 2 diabetes in Latino women 11‐26 months after pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes. Diabetes 1999; 48: 2430–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta‐analyses. Available from: http://wwwohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp.

- 21. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ades AE, Lu G, Higgins JP. The interpretation of random‐effects meta‐analysis in decision models. Med Decis Making 2005; 25: 646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Analyzing data and undertaking meta‐analyses In: Higgins J, Green S. (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 501. The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tobias A. Assessing the influence of a single study in meta‐analysis. Stata Tech Bull 1999; 47: 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994; 50: 1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Urs SSCS. Benefits of breastfeeding on development of diabetes mellitus, in women with history of gestational diabetes mellitus using the national health and nutrition examination survey. Value Health 2015; 18: A70. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gunderson EP, Jacobs DR Jr, Gross M, et al 25‐year prospective study of lactation duration and incidence of diabetes among cardia women screened before and after pregnancy. Diabetes 2014;63:A336–A337. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kjos SL, Henry O, Lee RM, et al The effect of lactation on glucose and lipid metabolism in women with recent gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 1993; 82: 451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buchanan TA, Xiang A, Kjos SL, et al Gestational diabetes: antepartum characteristics that predict postpartum glucose intolerance and type 2 diabetes in Latino women. Diabetes 1998; 47: 1302–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nelson AL, Le MH, Musherraf Z, et al Intermediate‐term glucose tolerance in women with a history of gestational diabetes: natural history and potential associations with breastfeeding and contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 198: 699.e691‐697; discussion 699.e697‐698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim SH, Kim MY, Yang JH, et al Nutritional risk factors of early development of postpartum prediabetes and diabetes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutrition 2011; 27: 782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Reilly MW, Avalos G, Dennedy MC, et al Atlantic DIP: high prevalence of abnormal glucose tolerance post partum is reduced by breast‐feeding in women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol 2011; 165: 953–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Capula C, Chiefari E, Vero A, et al Prevalence and predictors of postpartum glucose intolerance in Italian women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014; 105: 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gunderson EP, Hurston SR, Ning X, et al Lactation and progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 889–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moon JH, Kwak SH, Jung HS, et al Weight Gain and Progression to Type 2 Diabetes in Women With a History of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100: 3548–3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chamberlain CR, Oldenburg B, Wilson AN, et al Type 2 diabetes after gestational diabetes: greater than fourfold risk among Indigenous compared with non‐Indigenous Australian women. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016; 32: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Benhalima K, Jegers K, Devlieger R, et al Glucose Intolerance after a Recent History of Gestational Diabetes Based on the 2013 WHO Criteria. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0157272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Borgono CA, Retnakaran R. Higher breastfeeding intensity associated with improved postpartum glucose metabolism in women with recent gestational diabetes. Evid Based Med 2012; 17: e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tigas S, Sunehag A, Haymond MW. Metabolic adaptation to feeding and fasting during lactation in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Burnol AF, Leturque A, Ferre P, et al Increased insulin sensitivity and responsiveness during lactation in rats. Am J Physiol 1986; 251: E537–E541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jones RG, Ilic V, Williamson DH. Physiological significance of altered insulin metabolism in the conscious rat during lactation. Biochem J 1984; 220: 455–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lenz S, Kuhl C, Hornnes PJ, et al Influence of lactation on oral glucose tolerance in the puerperium. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1981; 98: 428–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cope MB, Allison DB. Critical review of the World Health Organization's (WHO) 2007 report on ‘evidence of the long‐term effects of breastfeeding: systematic reviews and meta‐analysis’ with respect to obesity. Obes Rev 2008; 9: 594–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bao W, Tobias DK, Bowers K, et al Physical activity and sedentary behaviors associated with risk of progression from gestational diabetes mellitus to type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174: 1047–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kojima N, Tanimura K, Deguchi M, et al Risk factors for postpartum glucose intolerance in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Gynecol Endocrinol 2016; 32: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tam WH, Yang XL, Chan JC, et al Progression to impaired glucose regulation, diabetes and metabolic syndrome in Chinese women with a past history of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2007; 23: 485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lauenborg J, Hansen T, Jensen DM, et al Increasing incidence of diabetes after gestational diabetes: a long‐term follow‐up in a Danish population. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1194–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stage E, Nørgård H, Damm P, et al Long‐term breast‐feeding in women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cordero L, Gabbe SG, Landon MB, et al Breastfeeding initiation in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Neonatal Perinatal Med 2013; 6: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Soltani H, Arden M. Factors associated with breastfeeding up to 6 months postpartum in mothers with diabetes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2009; 38: 586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Taylor JS, Kacmar JE, Nothnagle M, et al A systematic review of the literature associating breastfeeding with type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr 2005; 24: 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tanase‐Nakao K, Arata N, Kawasaki M, et al Potential protective effect of lactation against incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2017; 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Turcksin R, Bel S, Galjaard S, et al Maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation, intensity and duration: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr 2014; 10: 166–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 | Newcastle–Ottawa scale for quality assessment of included studies.