Abstract

Necrotizing fasciitis is an uncommon but often fatal disease. Given the various causes of necrotizing fasciitis, we report a case of sigmoid colon perforation caused by a toothpick subsequently resulting in fulminant necrotizing fasciitis of the retroperitoneum and right thigh successfully treated by hemipelvectomy and Hartmann´s procedure.

Keywords: intestinal perforation, necrotizing fasciitis, sepsis, hemipelvectomy

Introduction

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is an uncommon but potentially life threatening soft-tissue infection, which rapidly spreads along the fascia and the subcutaneous tissue 1. Wilson coined the term NF in 1952 describing a fascial necrosis, which is also the most consistent feature of the disease 2. NF occurring in the genital, perianal and perineal region is called Fournier's gangrene, named after Jean-Alfred Fournier, a Parisian venerologist of the 19th century 3. Its global incidence is low, reported with 0.4/100,000 per year with 500 - 1000 cases per year in the U.S. 4. The mortality rate varies in the literature from 8.7 to 76% despite surgical and antibiotic therapy, approaching nearly 100% without any treatment 5. In principle, NF can occur in any part of the body. However, it frequently occurs at the lower extremities, abdominal wall and the perineum 1. External trauma, often a minor injury, is the main reason for skin perforation and spreading of bacteria finally resulting in NF. Insect bites and injections are other reasons that may cause NF (Table 1) 1. Sarani et al. classified NF in four different types depending on the anatomy, microbial cause and depth of infection (Table 2) 6.

Table 1.

Etiology of NF of the lower extremities, abdominal wall and perineum (modified according to Green et al. (1996)).

| Soft tissue injury | Abdominal | Perineal | Genitourinary |

|---|---|---|---|

| - Animal or insect bite - Blunt or penetrating trauma - Cutaneous infections or ulcers - Illicit IV, IM, or subcutaneous drug injections - Postoperative complications - Sprained ankle - Subcutaneous insulin injection |

- Appendicitis - Colocutaneous fistula - Incarcerated hernia - Perforated viscus - Renal calculus |

- Anal dilatation - Fungating rectal carcinoma - Hemorrhoidal banding - Perirectal or ischiorectal abscess - Pilonidal abscess |

- Bartholin's gland duct abscess - Cervical or pudendal nerve block - Coital injury - Genitourinary infections - superimposed on Urethral stricture - Traumatic instrumentation - Urethral calculus Neoplasm - Prostatic massage - Postepisiotomy -Septic abortion - Vulvar abscess |

Table 2.

Classification system of NF (modified according to Misiakos et al. (2014)).

| Type / Microbial cause | Comorbidities | Infection of Location |

|---|---|---|

| I (polymicrobial, most common) | Diabetes mellitus | Trunk, perineum and abdomen |

| II (monomicrobial) | none | Extremities |

| III (Clostridium species, gram-negative bacteria, Vibrio spp.) | Seafood consumption trauma or external injuries | Trunk, perineum and abdomen |

| IV (fungal) | Immunosuppression | Extremities |

The low incidence of the disease and lack of typical clinical symptoms in its initial phase lead to misdiagnosis as either cellulitis, abscess or pyoderma 7. “Red flags” for NF are hypotension, hemorrhagic bullae and pain out of proportion 8. Non-specific signs such as erythema, edema and fever do not allow for a distinction between NF and other differential diagnosis such as phlegmons, erysipelas, cellulitis and pyomyositis 9. On this background, we present a rare cause of NF. An 'internal' trauma, namely a sigmoid colon perforation caused by a toothpick, was observed by postoperative computer tomography (CT) after the initial surgery.

Case report

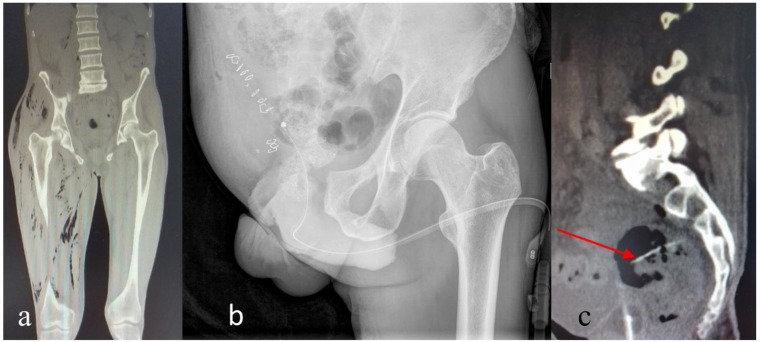

A 51-year-old patient was immediately transferred by colleagues from a local hospital with the suspicion of gas gangrene in his right lower abdomen and right leg after presentation through the emergency services. On admission to our hospital, there was an emphysema evident on the skin, the right thigh and right hypogastric region. The skin was warm with local tenderness of the right thigh and back. However, signs of peritonitis could not be found during initial examination. The patient was in septic shock. Vital signs were as follows: blood pressure: 100/50mmHg, mean arterial pressure 68mmHg, heart rate: 110bpm, body temperature 39,0°C (102.2°F). Fluid resuscitation has been performed with 2500ml Ringers´s lactate crystalloid within 3 hours prior to the transfer to our hospital. The CT of the abdomen and the lower limbs showed that gas formation appeared in the whole right thigh along the superficial and deep fascia extending cranially to the retroperitoneum along the iliopsoas muscle (Figure 1a). Initially, no foreign bodies in the patient´s intestines could be detected. Regarding the patients further medical history, only tobacco abuse and a nickel allergy were noted. He suffered from sciatica of the right leg for several months. It was treated by cortisone injections and oral use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Figure 1.

(a) CT scan prior to admission to our hospital. The coronal view shows retroperitoneal gas formation along the right iliopsoas muscle and all compartiments of the right thigh. (b) Postoperative X-ray control after right-sided hemipelvectomy. (c) The sagittal CT section of the abdomen and pelvis shows an acicular foreign body of 6cm length in the upper rectum.

Emergency surgery was performed. The muscles of the right thigh were deeply incised as usual for suspected NF. The muscles were found to be grey with malodor. The findings extended from the femur and proximal to the gluteus muscles and hip abductors. Thus, right hemipelvectomy was inevitable. Due to the retroperitoneal infestation, a double-transverse transversostoma was created simultaneously. Debridement into the healthy tissue was possible (Figure 1b). Histology confirmed the macroscopic findings. Extensive soft tissue as well as muscle necrosis could be evidenced. Furthermore, phlegmonous inflammation of subcutaneous and muscular tissue of the thigh close to the resection margin was described in the anatomical-pathological report. Empirical antibiotic fourfold therapy was initiated with Meropenem (3 x 1000mg/d i.v.), Linezolid (2 x 600mg/d i.v.), Penicillin G (24 million units per day i.v., divided into 6 doses) and Clindamycin (4 x 600mg/d i.v.). The rationale of the 4-fold therapy was suspected gas gangrene caused by Clostridium perfringens (therapy with Penicillin G and Clindamycin). Meropenem and Linezolid were administered empirically for multi-drug resistant organisms such as methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) pathogens. A postoperative CT scan showed an acicular foreign body of 6 cm length in the upper rectum (Figure 1c). Thus, a rectoscopy was performed and a toothpick perforating the sigmoid colon was found at 15cm ab ano, this was removed accordingly. In the absence of clinical improvement, a second control CT examination of the abdomen revealed a smooth and uniform thickening of the peritoneum indicating peritonitis and free intraabdominal air. Thus, immediate laparotomy was necessary. A larger perforation of the sigmoid colon with pronounced peritonitis could be discovered. The sigmoid colon had to be resected, the transversostoma was rearranged and a proctosigmoidectomy (Hartmann's procedure) was carried out. Afterwards, the clinical condition of the patient improved quickly. A total of three further wound revisions of the right pelvis were necessary until a plastic coverage by rotation flap surgery was possible. In the course of the ICU stay and surgical treatment, ESBL- Escherichia coli could be identified as microbiological pathogen after cultivation of swabs, tissue samples and blood cultures. After sepsis was successfully dominated, antibiotic therapy according to resistogram was deescalated to Meropenem monotherapy 5 days after initial surgery. After another 10 days of Meropenem monotherapy, Levofloxacin 500mg was administered orally twice a day for an additional 15 days. It was then discontinued due to improved clinical wound findings and reduced local inflammatory markers. After an 18 days lasting stay in our ICU, the patient was mobilized with the use of forearm crutches on the normal ward and transferred to rehabilitation 7 weeks after admission. How and when the toothpick was ingested could not be elucidated retrospectively.

Discussion

The fatal course of the disease, if diagnosed incorrectly or too late, requires surgeons to deal with diagnosis and treatment of NF rather promptly. The case above represents a typical situation, surgeons are faced with in emergency departments. The current patient was transferred by colleagues needing support in the knowledge that a center of maximum care provides surgical and intensive care capacities, which are needed in such challenging cases. The presentation of the patient with subcutaneous emphysema of the right thigh and the hypogastric region with septic shock must rise the suspicion of NF. In the presented case, CT could illustrate the advanced state of gas formation within the right thigh and retroperitoneum indicating NF. Sectional imaging is recommended if the condition of the patient allows for its performance and surgical therapy is not delayed 10. Nevertheless, clinical suspicion of NF makes prompt surgical exploration and biopsy for both histological and microbiological diagnostics necessary. After confirmation of infestation of the fascia of the deep hip and pelvic musculature, emergency amputation of the right leg in the form of a hemipelvectomy in accordance with the rule “life before limb” was carried out and a double-transverse transversostoma was performed by means of a laparotomy. Appropriate debridement and accompanied early broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy are cornerstones of treatment. Sometimes amputation of extremities is inevitable, though 1. Postoperative CT scans, which are not routinely recommended, can help to control the surgical success in terms of control of further expansion of fasciitis or emphysema. MRI and CT scans can uncover fascial thickening, intramuscular fluid collection and soft tissue gas, which is produced by gas-forming organisms 11. In this case, the perforation of the sigmoid colon by a toothpick, which was not seen on an initial CT could be detected by this postoperative imaging modality. While reports of perforations of the intestine due to diverticulitis or carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract resulting in NF of the retroperitoneum and the thigh are not uncommon, only one other case of a toothpick perforation resulting in NF is documented in literature 12. The only proven bacterium, ESBL Escherichia coli, could have been a hint, that cortisone injections as supposed iatrogenic cause of infection might not be the reason for NF in this case. The operative situs with perforation of the sigmoid colon and pronounced peritonitis indicate that the intestinal toothpick perforation was most likely the reason for NF.

Conclusion

NF is a rare but fulminant disease which requires courageous therapeutic decision-making. For the wellbeing of NF patients, all diagnostic and therapeutic means have to be exploited. With no improvement despite appropriate therapy, extensive diagnostics should be performed to figure out the reason of failed treatment success.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Abdullah Ismat for linguistic editing of the manuscript.

Authors´ contributions

M.R. and V.A. participated in the design and interpretation of the manuscript. M.R., G.K. and D.W. participated in drafting and revising of the manuscript. C.H. and V.A. provided administrative, technical and supervisory support. In addition, they participated in the interpretation and revising the manuscript. All authors finally approved the manuscript being published.

References

- 1.Green RJ, Dafoe DC, Rajfin TA. Necrotizing fasciitis. Chest. 1996;110:219–29. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Am Surg. 1952;18:416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thwaini A, Khan A, Malik A, Cherian J, Barua J, Shergill I. et al. Fournier's gangrene and its emergency management. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:516–9. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.042069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Study OGAS, Kaul R, McGeer A, Low DE, Green K, Schwartz B. et al. Population-based surveillance for group A streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis: clinical features, prognostic indicators, and microbiologic analysis of seventy-seven cases. Am J Med. 1997;103:18–24. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Patapis P, Sotiropoulos D, Kanavidis P, Machairas A. Current concepts in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Front Surg. 2014;1:36. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, Schwab CW. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiralj A, Janjić Z, Nikolić J, Markov B, Marinković M. A 5-year retrospective analysis of necrotizing fasciitis: A single center experiences. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2015;72:258–64. doi: 10.2298/vsp131223081k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun X, Xie T. Management of Necrotizing Fasciitis and Its Surgical Aspects. Int J Low Extrem Wounds; 2015. p. 1534734615606522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YS, Wong CH, Tay YK. Staging of necrotizing fasciitis based on the evolving cutaneous features. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1036–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wysoki MG, Santora TA, Shah RM, Friedman AC. Necrotizing fasciitis: CT characteristics. Radiology. 1997;203:859–63. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malghem J, Lecouvet FE, Omoumi P, Maldague BE, Berg BCV. Necrotizing fasciitis: contribution and limitations of diagnostic imaging. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80:146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee I-H, How C-K, Chen J-D, Yen DH-T, Chiu Y-H. Right Hip Necrotizing Fasciitis. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:499. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181f3cc12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]