Abstract

Purpose

To synthesize factors influencing the activation of the rapid response system (RRS) and reasons for suboptimal RRS activation by ward nurses and junior physicians.

Data sources

Nine electronic databases were searched for articles published between January 1995 and January 2016 in addition to a hand-search of reference lists and relevant journals.

Study selection

Published primary studies conducted in adult general ward settings and involved the experiences and views of ward nurses and/or junior physicians in RRS activation were included.

Data extraction

Data on design, methods and key findings were extracted and collated.

Results of data synthesis

Thirty studies were included for the review. The process to RRS activation was influenced by the perceptions and clinical experiences of ward nurses and physicians, and facilitated by tools and technologies, including the sensitivity and specificity of the activation criteria, and monitoring technology. However, the task of enacting the RRS activations was challenged by seeking further justification, deliberating over reactions from the rapid response team and the impact of workload and staffing. Finally, adherence to the traditional model of escalation of care, support from colleagues and hospital leaders, and staff training were organizational factors that influence RRS activation.

Conclusion

This review suggests that the factors influencing RRS activation originated from a combination of socio-cultural, organizational and technical aspects. Institutions that strive for improvements in the existing RRS or are considering to adopt the RRS should consider the complex interactions between people and the elements of technologies, tasks, environment and organization in healthcare settings.

Keywords: patient safety, human factors, rapid response system, clinical deterioration, early warning scoring system, systematic review

Introduction

There has been a growing body of research that focus on recognizing and responding to clinically deteriorating patients in general ward settings in the past decade [1–4]. Much of this interest was prompted by studies that demonstrated patient deterioration not being recognized and responded to in a timely manner [5–10]. This lapse in patient care has led to an increase risk and incidences of serious adverse events such as unplanned admissions to intensive care units, in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests, and unexpected deaths [11, 12]. Improving timely recognition and prompt interventions is therefore pivotal to the provision of safe and quality care to a deteriorating patient before his condition becomes life-threatening [13].

International concerns over delays or failure to recognize and escalate care for clinically deteriorating ward patients have led to the widespread implementation of a hospital-wide patient safety initiative known as the rapid response system (RRS) in acute hospitals [14, 15]. The RRS is designed with afferent and efferent components, and mechanisms for quality control, audit and administration [16]. The afferent arm involves monitoring and identifying deteriorating patients using a set of activation criteria, commonly known as the Early Warning Scoring System (EWSS), which is based on abnormal vital signs and/or observations such as threatened airway, declined neurological status and staff concerns (‘worried’ criterion) [17–19]. Once a patient meets the activation criteria, the efferent arm, i.e. the rapid response team (RRT) or medical emergency team (MET), comprising personnel with critical care expertise and diagnostic skills, will be activated to swiftly bring critical care expertise to the deteriorating patient [13, 17]. The RRS bypasses the traditional hierarchical escalation of care by sanctioning bedside nurses and junior physicians to promptly access senior medical assistance, outside the primary physician team’s chain of command [13, 16, 20].

Theoretically, the RRS offers significant advantages over the traditional referral model of care and potentially decreases resuscitation events in general wards [21]. However, two decades of research still demonstrate mixed evidence on the effectiveness of the RRS in achieving their stated aims to reduce resuscitation events outside of the ICU, unplanned ICU admissions and hospital mortality [22–28]. Some proponents have questioned the existence of the tangible benefits of the RRS and suggested the need for higher level research and randomized controlled trials while others argued that the benefits are self-evident. Several authors have also attributed the conflicting evidence regarding the effectiveness of the RRS to delay or failure in ward clinicians to activate the RRT despite patients fulfilling the activation criteria [24, 27, 29–32]. An epidemiology review of adult RRT patients in Australia revealed that close to 50% of the activations were delayed [33]. Apart from cognitive failure to recognize the need for RRS activation, socio-cultural factors and professional hierarchies are also strong reasons that impede adherence to the RRS protocol [34–39]. Existing studies found that junior physicians were reluctant to breach the traditional system of patient management while ward nurses feared being reprimanded if they bypassed attending physicians [21, 31, 40]. This highlights the need for a detailed analysis to understand individual and work system issues that may prevent frontline ward clinicians from activating the RRS.

Therefore, this review aims to synthesize and summarize the factors influencing an activation of the RRS by ward nurses and junior physicians in general wards. This review is also anticipated to identify reasons for suboptimal activation of the RRS, and highlight gaps for further research.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was used to guide the reporting of this systematic review [41].

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for inclusion of articles in the review

| PICOS | Details of eligibility |

|---|---|

| Population | Ward nurses and junior physicians (residents, medical officers and house officers). |

| Phenomena of Interest | Articles related to factors influencing the RRS activation for adult patients in general wards by frontline ward clinicians and/or frontline ward clinicians’ attitudes, perceptions and experiences of the RRS were included. |

| Articles related to evaluating the effectiveness or impact of the RRS on patient outcomes and/or involved patients with the ‘Do-Not-Resuscitate’ order were excluded. | |

| Context | Conducted in adult general ward settings. |

| Articles conducted in rural, obstetric and gynecological, pediatrics and mental-health settings, as well as outside of the adult general ward settings were excluded. | |

| Study design | Original primary studies of any design in the English language published between January 1995 and January 2016 were included. The year 1995 was chosen as the cut-off date as it marked the first study outlining the concept of the RRS. |

| Only full text articles were included. | |

| Conference abstracts or proceedings were excluded due to insufficient study details. | |

| General editorials, case reports, and gray literature were excluded to provide a level of quality control and to reflect evidence-based practice. |

PICOS, Population, Phenomena of Interest, Context, Study design; RRS, rapid response system.

Information sources

A comprehensive search was performed included searching relevant electronic databases (CINHAL, PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, PsycINFO and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database), mining the reference lists of selected articles, and hand-searching Resuscitation and BMJ Quality & Safety, which are known for publishing articles related to the RRS and/or patient deterioration.

Search

Three broad search key concepts were developed: RRS, EWSS and deteriorating ward patients. Thesaurus terms of these concepts were used. Search terms were used singly and/or in combination (Appendix 1 contains the full search strategy). Literature that was published between January 1995 and January 2016 was searched. The year 1995 was chosen as the cut-off date as it marked the first published literature outlining the concept of the RRS [42].

Study selection

One reviewer (WLC) screened the titles and abstracts of relevant articles before conducting a full-text review while meeting regularly with the two other reviewers (MTAS & SYL) to discuss article eligibility. Reasons for exclusion were recorded.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed to catalog the author(s), publication year, study aims, country and setting of study, sample, methods for data collection and data analyses, and relevant key findings. Data were extracted independently by WLC, then reviewed by SYL. Differences were resolved by discussions among the two reviewers.

Quality assessment

All included studies were appraised independently by WLC and MTAS using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [43] for qualitative studies, Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument [44] for quantitative studies, and Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools [45] for mixed-method studies. Articles were scored against each item in the appraisal checklist by scores of not met (‘0’), partially met (‘0.5’), fully met (‘1’), or unsure. A total study quality percentage was tabulated. Depending on the total appraisal score, the included articles were classified as low (<50%), medium (50–70%), or high (>70%) quality. The results were compared and disagreements were resolved by consultation with SYL.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis adopted the integrated design for mixed research synthesis [46] and the hybrid process of inductive and deductive thematic analysis [47]. The synthesis began with converting the extracted quantitative findings into qualitative forms, i.e. free codes, and, together with the extracted qualitative findings, was subjected to the inductive portion of a hybrid thematic analysis.

Themes that explored the relevance of the categories of codes in the context of the research question were developed. The deductive portion involved categorizing the inductively developed themes into a conceptual framework [47]. While the process was initially undertaken by WLC, the groupings were further refined by discussions with the co-authors and rechecking of the included studies.

Results

Search results

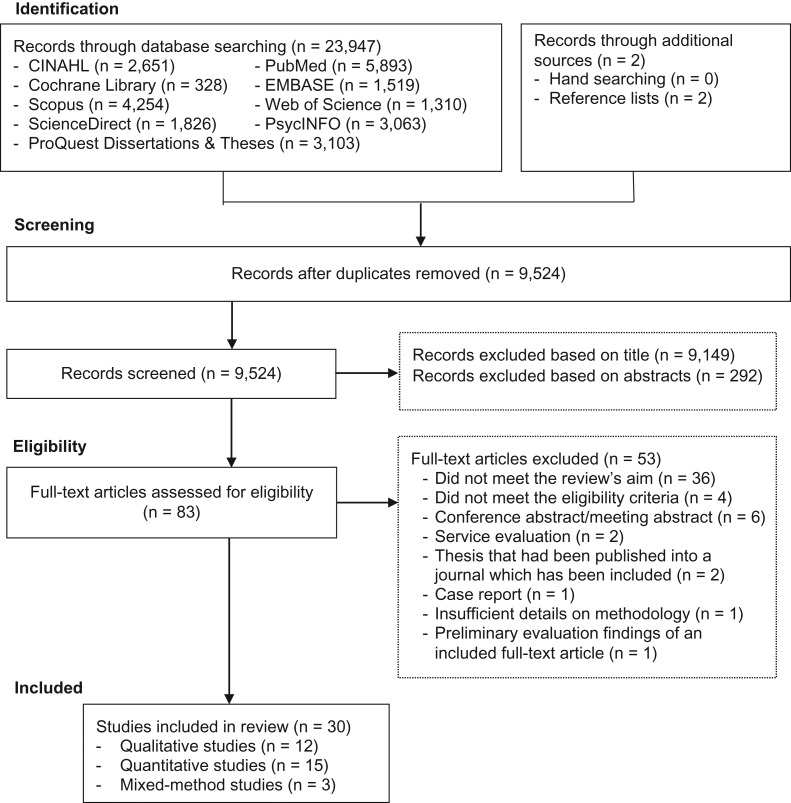

The search strategy yielded 9524 records after removing duplicated articles. Following the review of titles and abstracts, 83 articles were selected for full-text review, from which 53 articles were excluded, leaving 30 studies for this review [21, 37–40, 48–72] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process.

Study characteristics

Studies originated from the United States (US) (n = 14), Australia (n = 10), the United Kingdom (n = 2), along with one study each from Canada, Finland, Greece, and Italy. The study setting included acute and tertiary care (n = 19), community hospitals (n = 4), and mixed-settings (n = 7). Eight studies were multi-site studies. The median sample sizes were 32 participants for qualitative studies, 246 participants for quantitative studies and 407 medical record reviews and 10 participants for mixed-method studies. The population studied included ward nurses (n = 16), physicians (n = 1), both nurses and physicians (n = 7), a mixture of healthcare professionals (n = 4), and general ward patients (n = 2).

There were 15 quantitative, 12 qualitative and 3 mixed-methods studies. Most quantitative studies were self-administered survey-based studies (n = 12), except for one study, which employed face-to-face surveys. Reviews of medical records and RRT activations were used in five studies, with three of these studies using record review in conjunction with a qualitative approach (mixed-method studies). Qualitative data were collected through interviews (n = 9) and focus groups (n = 3). Table 2 summarizes the included studies.

Table 2.

Summary of study characteristics (n = 30)

| Author | Study aim(s) | Country & setting | Years of RRS | Methods | Relevant key findings | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astroth et al. [48] | To identify barriers and facilitators to nurses’ decisions regarding activation of RRTs | US, community hospital | NS |

|

Facilitators:

|

High |

| Bagshaw et al. [49] | To evaluate nurses’ beliefs and behaviors about the MET system. | Canada, teaching hospital | 3 |

|

|

Medium |

| Benin et al. [50] | To qualitatively describe the experiences of and attitudes held by nurses, physicians, administrators and staff regarding RRT | US, teaching hospital | 3 |

|

|

High |

| Braaten [51] | Using cognitive work analysis to describe factors within a hospital system that shaped medical-surgical nurses’ RRT activation behavior | US, acute care hospital | 7 |

|

|

Medium |

| Butcher et al. [52] | To determine whether resident physicians perceive education benefit from collaboration with RRT and the impact of RRT on their clinical autonomy | US, acute tertiary hospitals | 7 |

|

|

Medium |

| Cioffi [53] | To explore the experiences of nurses calling the MET to ward patients who require early medical interventions | Australia, acute tertiary hospital | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Cioffi [54] | To investigate nurses’ use of past experiences in the decision-making process to call the MET | Australia, acute tertiary hospital | NS |

|

|

High |

| Cretikos et al. [55] | To measure the process of the implementation of the MET system and to identify factors associated with the level of MET utilization | Australia, acute tertiary hospitals (n = 12) | ½ |

|

|

Medium |

| Davies et al. [56] | To identify and assess the types and prevalence of barriers associated to the activation of the RRS by clinical staff | US, community hospital | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Donohue and Endacott [57] | To examine ward nurses and critical care outreach team perceptions of the management of patients who deteriorate in acute wards | UK, acute tertiary hospital | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Douglas et al. [21] | To explore and compare nursing and medical staff's perceptions of Medical Emergency Response Team (MERT) use | Australia, tertiary hospital | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Green and Allison [58] | To explore nursing and medical staff’s perceptions, attitudes, perceived understanding of a clinical marker referral tool implemented to assist in early identification and referral of unstable patients in the general wards | Australia, tertiary hospital | <½ |

|

|

Medium |

| Jenkins et al. [59] | To explore the non-ICU nurses’ perceptions of facilitators and barriers to RRT activation | US, community hospital | 9 |

|

|

Medium |

| Jones et al. [37] | To assess whether nurses value the MET service and to determine whether barriers to calling MET exist | Australia, acute tertiary hospital | 4 |

|

|

Medium |

| Kitto et al. [38] | To examine medical and nursing staff members’ experiences of the RRS and to explore social, professional and cultural factors that mediate RRS usage | Australia, mixed settings (n = 4) | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Leach et al. [60] | To investigate how RNs rescue patients in hospitals where RRTs are in place and to understand the processes involved in making the decision to call the RRT | US, acute hospitals (n = 6) | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Massey et al. [61] | To explore nurses’ experiences of using and activating a MET, and to understand facilitators and barriers to nurses’ use of the MET | Australia, teaching hospital | NS |

|

|

High |

| Pantazpoulos et al. [62] | To evaluate the relationship between nurse demographics and correct identification of clinical situations warranting specific nursing actions, including MET activation | Greece, tertiary hospital | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Pattison and Eastham [63] | To explore referrals to CCOT, the associate factors around patient management and survival to discharge, and the qualitative exploration of CCOT referral characteristics | UK, specialist hospital | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Radeschi et al. [64] | To identify the attitudes and barriers to MET utilization among both ward nurses and physicians and to investigate whether these attitudes and barriers are influenced by participation in a specific educational program of MET | Italy, mixed settings (n = 10) | NS |

|

|

High |

| Robert [65] | To explore the experiences of staff nurses using intuition in the process of activating RRT for patients being cared for in medical-surgical and telemetry units. | US, acute hospital | 5 |

|

|

High |

| Salamonson et al. [66] | To explore nurses’ satisfaction with the MET, perceived benefits and suggestions for improvement, and to examine the characteristics of nurses who were more likely to activate the MET | Australia, acute hospital | NS |

|

|

Medium |

| Sarani et al. [67] | To assess the perceptions of physicians and registered nurses about the effects of a MET on patient safety and their own educational experiences | US, acute tertiary hospital | 1 |

|

|

Medium |

| Schiid-Mazzoccoli et al. [68] | To compare differences in nurse, patient and organizational characteristics in medical and surgical patients requiring a MET activation | US, tertiary hospital | 15–17 |

|

|

High |

| Shapiro et al. [40] | To described the impact of RRTs on staff nurses’ practice, perspectives, experiences and challenges when RRTs are used. | US, mixed settings (n = 18) | NS |

|

|

High |

| Shearer et al. [39] | To determine the incidence of clinical staff failing to call the RRS and the socio-cultural barriers to failure to activate the RRS | Australia, mixed settings (n = 4) | 3–13 |

|

|

High |

| Stewart et al. [69] | To evaluate the impact of the implementation of the MEWS on the early identification of patients at risk for clinical deterioration and factors that influence how nurses use MEWS as a framework in the decision-making process for RRS activation | US, acute care hospital | 1 year |

|

|

High |

| Tirkkonen et al. [70] | Using the Ustein template to study documentation of vitals before a MET call, with special reference to patients having automated patient monitoring in general ward and to identify factors associated with delayed MET activation | Finland, tertiary hospital | <1 |

|

|

High |

| Williams et al. [71] | To describe nurses’ experiences and perceptions of RRT | US, community hospital | 4 |

|

|

High |

| Wynn et al. [72] | To examine nurse characteristics and nursing action related to RRT calls | US, acute tertiary medical center | 1 |

|

|

Medium |

RRT, rapid response team; US, United States; NS, not specify; MET, medical emergency team; RRS, rapid response system; RN, registered nurse; UK, United Kingdom; ICU, intensive care unit; CCOT, critical care outreach team; MEWS, modified early warning system; METal, medical emergency team alert.

Quality assessment

The overall quality assessment of the study was medium (n = 18) to high (n = 12) (Appendix 2), with a substantial overall agreement of 83.3% between WLC and MTAS (Kappa = 0.658, P < 0.001).

The studies were generally good at providing clear research aims, congruity between the research aims and research design, providing details on the sample, and outlining the data collection and data analysis methods. More than half of the qualitative studies had inadequate clarifications for ethical issues and failed to consider the effect of the researcher–participant relationship.

The main weaknesses of the quantitative studies were the lack of considerations for confounders and insufficient psychometric evaluation of the different questionnaires administered. Only five studies addressed confounders using a statistical approach [21, 64, 67, 68, 72]. More than half of the studies have limited generalizability, given the small sample size and non-response bias due to poor response rates.

All the mixed-method studies had inadequate justifications for the need of a mixed-method design to address their research questions and did not consider the limitations associated with integration of qualitative and quantitative data.

Synthesis of results

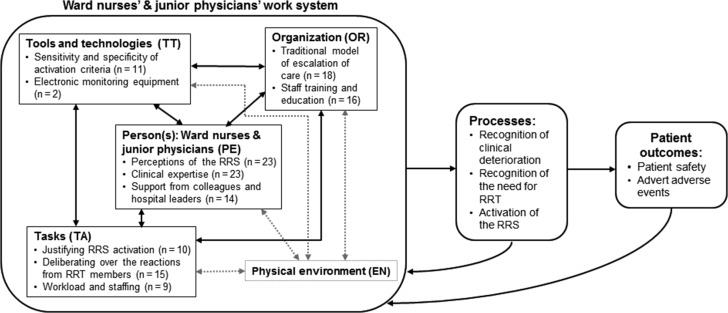

The Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model of work system and patient safety developed by Carayon et al. is used as a conceptual framework to understand the barriers and facilitators to activation of the RRS by ward nurses and junior physicians [73]. The SEIPS model provides a framework for understanding the impact of work system factors on healthcare processes and patient outcomes [73]. The factors identified were grouped into 10 themes, which were then categorized into the five interacting components of the work systems of the SEIPS model: the person[s] using various tools and technologies to perform tasks in an environment under certain organizational conditions [73]. The interaction of these components of the work systems influences the processes of RRS activation, which in turn affects patient outcomes. At the same time, feedback loops between the process and outcomes, and the work systems can inform problems and opportunities for modifying the work systems [73, 74].

Figure 2 depicts an adapted graphical representation of a ward clinician’s work system that influences RRS activation. Factors influencing RRS activation were distributed across person, tools and technologies, tasks, and organization. No factor was identified in the environment component. Table 3a–3d provides an explanation and supporting evidence for each of the factors identified

Fig. 2.

The application of SEIPS model to ward clinicians’ work system in the activation of the rapid response system. Dotted arrows and box: No identified interacting relationship between physical environment and the rest of the work system components (person, tools and technologies, tasks and organization). Descriptions of work system components (adapted from SEIPS model by Carayon et al. [73]). PE: Physical, cognitive, or psychosocial characteristics or conditions of an individual at the center of the work system. TT: Objects or instruments that the person(s) uses to do work or assist people in doing work (RRS activation). TA: Characteristics of the task such as difficulty, variety and sequence of work performed by the person(s) to accomplish the objectives. OR: Organizational conditions governing or influencing the way the person(s) performs tasks using tools and technologies in a specific environment. EN: Physical characteristics of the environment where work is performed.

Table 3a.

Person-related factors influencing an activation of the rapid response system by ward nurses and junior physicians

| Themes | Explanation | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Perceptions of the RRS |

|

|

| Clinical expertise |

|

|

| Support from colleagues and hospital leaders | Ward nurses received support from their fellow nursing peers and hospital leaders in an activation of the RRS despite facing resistance from the attending physicians |

|

‘Person’, which refers to ward nurses and junior physicians in this review, is at the center of the work system. The process to activation of the RRS was found to be affected by person-related factors such as perceptions of the benefits and drawbacks of the RRS, clinical expertise, and support received from colleagues and hospital leadership in the activation of the RRS (Table 3a). Although the process was also aided by ‘tools and technologies’, there was apprehension about the ability of the tools and technologies to support early recognition of patient deterioration and RRS activation, particularly on the issues of sensitivity and specificity of the activation criteria and the limitations of the monitoring technology (Table 3b). The enactment of activating the RRS was made complex with the ‘task’ of seeking justification and affirmation, deliberating over reactions from the RRT, and taking into consideration the workload and staffing (Table 3c). Adherence to the traditional model of escalation of care and staff education were powerful ‘organizational’ factors that influenced the way ward clinicians used tools and technologies, and performed their tasks of activating the RRS (Table 3d).

Table 3b.

Tools and technology-related factors influencing an activation of the rapid response system by ward nurses and junior physicians

| Themes | Explanation | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity and specificity of activation criteria | The sensitivity and specificity of the activation criteria have been criticized despite its ability to facilitate ward clinicians in the recognition of patient deterioration |

|

| Electronic monitoring equipment | The idea of electronic monitoring equipment is to facilitate the observation and identification of deteriorating patients. However, its limitations may outsmart itself and in turn compromise patient safety | Only two studies discussed the influence of electronic monitoring equipment on RRS activations, but both did not demonstrate positive effects [51, 70]. One study reported that electronic monitoring without real-time capture of vital signs may delay entry and errors in transcribing, thus delaying the recognition of clinical deterioration [51]. The other study observed that failure and delayed RRS activations was almost twice in automated monitored patients (81%) compared to non-automated monitored patients (53%) (P < 0.001) [70]. One possible offered explanation was alarm fatigue from an oversensitive activation criteria, which resulted in ward staff being desensitized to deranged vital signs [70] |

Table 3c.

Task-related factors influencing an activation of the rapid response system by ward nurses and junior physicians

| Themes | Explanation | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Justifying RRS activation | The task of justifying RRS activations by nurses was common for patients who experience subjective, subtle, and/or gradual clinical changes | Ten studies described that nurses’ decision to activate the RRS was often moderated by the task of justifying the need for a RRT through seeking affirmation from peers or more experienced nurses and/or gathering clinical data to avoid unnecessary activation [38, 39, 48, 51, 53, 60, 61, 65, 69, 71]. At times, justification included beyond seeking affirmation to ‘dig deeper’ (p.26) into gathering further objective data, identify an objective finding that served as a ‘trigger’ (p.27) for RRS activation, or even ‘to wait for a bigger change’ (p.28) to occur [51]. Common reasons for the need in justification included the fear of making ‘incorrect’ calls, lack of confidence in patient assessment, misunderstanding of the activation criteria, and inadequacy of the activation criteria [38, 39, 48, 51, 53, 60, 61, 65] |

| Deliberating over the reactions from RRT members | Ward clinicians’ decision in an activation of the RRS was confronted with the task of deliberating over the attitudes and responses from the RRT members. The collaboration between attending physicians and the RRT members also affects RRS activation | Fourteen studies suggested the task of deliberating over reactions from the RRT members when deciding whether or not to activate the RRS [37, 38, 40, 48–50, 55, 59–61, 63, 64, 66, 69, 71]. Dismissive responses and behaviors from the RRT members such as condescension in tone, arrogant communication styles and negative repercussions by the RRT for unnecessary activations discouraged RRS activations [38, 48, 49, 55, 59, 61, 63, 64, 66, 69, 71] while collegial working relationship between ward clinicians and RRT members achieved through effective communication and mutual respect encouraged RRS activation [60]. Conflicting medical opinions regarding patient management between attending physicians and members of the RRT also hampered RRS activation [49, 50, 63] |

| Workload and staffing | Workload and staffing have bidirectional influences on RRS activation. While heavy workload and inadequate staffing can cause ward clinicians to feel handicapped in supporting deteriorating patients, it can also hinder their ability to provide vigilance to patients |

|

Table 3d.

Organization-related factors influencing an activation of the rapid response system by ward nurses and junior physicians

| Themes | Explanation | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional model of escalation of care | The RRS ‘breaks’ away from the traditional model of escalation of care, which is inherently rigid to change, especially among the medical profession |

|

| Staff training and education (n = 18) | Staff training and education about the RRS is not only crucial in the implementation of the RRS but also imperative in the maintenance phase in order to enhance the acceptance and uptake of the RRS | Eighteen studies identified that staff training and education on the purpose of the RRS, understanding and familiarity with the activation criteria and RRS activation protocols, and ability to identify deteriorating patient situations who require a RRT review were vital facilitators to RRS activation [21, 37, 38, 40, 48–50, 53, 55, 56, 59–64, 66, 72]. Conversely, unclear RRS protocols and guidelines to define individual roles and responsibilities impeded RRS activations [40, 48–50, 59]. In addition, cursory initial training on the RRS and sporadic follow-ups on RRS education were key reasons to unfamiliarity with the RRS protocols and confusion in individual roles during a joint rescue with the RRT [59]. Conventional education and training methods such as orientation sessions, lectures, and posters may not be adequately effective [56] |

The findings from this systematic review led us to confirm that the process to the activation of the RRS is complex and multifactorial, but underpinned by well-defined themes in the work systems of ward clinicians.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to synthesize evidence on the factors influencing RRS activation by junior physicians and ward nurses. Using the SEIPS model, we found that the elements of person, tools and technologies, tasks, and organization were associated with RRS activation. No factor associated with physical work environment was identified. This may be due to a lack of awareness and studies examining the ergonomics of workplace on RRS activations. Nevertheless, our findings validate and expand upon the findings of a previous literature review on factors that affect nurses’ effective use of the RRT [75].

The application of the SEIPS model enabled a clearer connection of the interactions of different factors in the work systems factors which influences the recognition of the need for RRT and activation of the RRS (processes) to effectively avert adverse events (outcome) resulting from uninterrupted clinical deterioration. For example, ward nurses’ adherence to the traditional model of escalation of care was associated with their fear of criticism for ‘incorrect’ activations. Their fear of criticism is linked to a combination of insufficient clinical experience (person-related), inadequacy in the activation criteria (tools and technological-related), and dismissive responses from RRT members (task-related), which often leads to ward nurses hankering after an affirmation for RRS activation. Experienced nurses were found to be more confident and capable in recognizing the need for RRT interventions based on their intuitions. Hence, they were often consulted by their juniors when an affirmation is needed.

The inadequacy of the activation criteria to detect subtle and early deterioration highlights that acquiescent reliance on the activation criteria, with vital signs derangements as the optimal cue for RRS activation, can marginalize other assessment cues [76, 77]. Overreliance on vital signs abnormalities also risks devaluing the merit of subjective data and intuitive senses within assessment reflecting early deterioration [78]. Patient assessment using sensory skills such as visual observation, palpation and listening, which aid early detection of deterioration before vital signs changes are evident, should not be compromised or replaced with electronic monitoring equipment [79–81]. It is thus essential that clinicians are equipped with the ability to conduct and interpret appropriate patient assessments. Furthermore, an overreliance on automated patient monitoring can lead to a tendency to have strong belief in the accuracy of the monitoring technology with a low degree of suspicion of error [82]. This could cause nurses to be less vigilant to patients’ deteriorating conditions, thus likely to jeopardize patient safety [82].

Similar to the ward nurses, adherence to the traditional model of calling attending physicians first was the biggest barrier for junior physicians. Our findings suggest that this barrier could be attributed to their perception of threatened deskilling due to the presence of the RRT. Resistance from the medical profession towards the acceptance of the RRS due to perceived disruptive effects on junior physicians’ education and clinical autonomy can be linked to the professional socialization in medicine education where physicians laid claims to their expertise and jurisdictions over patient management [85, 86]. As such, RRS activation could be deemed as incompetent and at odds with the socialization process of becoming an independent practitioner.

An initiation of the RRS involves a complex cultural system of change, which is superimposed on professional norms and boundaries in a strictly hierarchical context [83]. This initiative may be difficult to adopt unless all healthcare practitioners within an organization collectively agree to use the system [84]. Thus, hospital leaders play an essential role in transforming individual thinking, organizational culture and professional hierarchy in medicine. While it takes time for attitudes and behaviors to alter, and organizational cultural changes to be embedded, hospital leaders can introduce some quick wins as the first steps towards garnering support and acceptance from stakeholders of the RRS [87].

Implications for clinicians and policymakers, and future research

Our findings demonstrate that frontline clinicians were convinced about the value of the RRS. However, timely RRS activations should be encouraged with appropriate support. Given that junior nurses’ first course of action when uncertain about the need for a RRS activation was to seek affirmation from senior nurses, an adequate skill mix of experienced nurses on shift thus becomes apparent. The considerable amount of time spent justifying RRS activation limits the RRS as an early intervention to clinical deterioration. Thus, further work is required to integrate relevant patient assessment skills and early cues of deterioration into the EWSS activation criteria, as well as equip clinicians with a more clinically specified understanding of the ‘worried’ criterion that is less open to subjective interpretation [21, 88, 89]. Future studies can also examine the impact of clinicians’ decision-making process on timely RRS activations and patient outcome. The lack of substantial evidence on the influence of monitoring technology also recommends research to assess the impact of monitoring technology on timely activations and patient outcome.

Socio-cultural barriers such as adherence to the traditional hierarchical escalation of care, fear of criticism and negative behaviors of the RRT responders could be mediated by hospital leaders. This can be achieved through continuous training coupled with appropriate education and training methods to encourage teamwork and clinicians to respond responsibly, clear RRS protocols, and continuously support advocating RRS activations. An exploration of other viable modes of education and training methods is warranted. Literature has highlighted that certain cultures tend to adopt vertical hierarchies in their working relationships [90], which could potentially be an obstacle to RRS activation. Future studies should be conducted beyond a non-Western context, which was not included in this review.

It is also paramount that hospital leaders periodically evaluate their hospital RRS. An important aspect not to be overlooked is the perspectives of ward nurses and junior physicians, who are key users of the RRS. Understanding the impact of the RRS on junior physicians’ medical education holds strong promise to enhance the implementation process of the RRS in institutions and improve physicians’ acceptance of the RRS. Researchers may seek to develop a tool to help hospital leaders identify core factors to improve each hospital’s RRS. Lastly, this review recommends the adoption of human factors ergonomics perspectives to understand the interactions between the end-users of the RRS and other elements of the work system to further optimize and mitigate obstacles associated with the RRS.

Limitations

Despite an exhaustive literature search, the exclusion of studies that evaluated the effectiveness or impact of the RRS on patient outcomes, which may contain additional insights, may have been missed. Secondly, most of the quantitative studies were cross-sectional surveys that provided information about attributes at a single time-point. It is likely that the perceptions of responders will change overtime. Thirdly, there are variations in the RRS implemented across the included studies i.e. the maturity of the RRS and different composition of the RRT (physician-led RRT versus nurse-led RRT). This may have an influence on ward clinicians’ decisions to activate the RRT. Fourthly, as most of the studies did not report the RRS activation rates, we could not analyze the identified factors in relation to the activation frequency. Lastly, the use of a different conceptual model might have resulted in different themes identified.

Conclusion

This systematic review has demonstrated that RRS activation is a complex intervention that involves navigating through the way clinicians interact with the interplay of socio-cultural, political and organizational considerations. Activations of the RRS were found to be influenced by key factors that include frontline clinicians’ perceptions of the RRS and their clinical judgment, support from colleagues and hospital leaders, adequacy of the activation criteria, attitudes and responses of the RRT members, adherence to the traditional model of escalation of care, and staff training and education. Institutions should consider these factors in the implementation of their RRS and develop strategies to improve the utilization of the RRS. More research efforts, along with clinical practice implications, should be central to improving suboptimal activations of the RRS.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at International Journal for Quality in Health Care online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NUHS Medical Publications Support Unit, Singapore, for providing editing services to this manuscript.

References

- 1. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Recognising and Responding to Clinical Deterioration. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Institute for Healthcare Improvement 5 Million Lives Campaign. Getting Started Kit: Rapid Response Teams. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Acutely Ill Patients in Hospital: Recognition of and Response to Acute Illness in Adults in Hospital. London, England: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Care of Deteriorating Patients. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeVita MA, Bellomo R, Hillman K et al. . Findings of the first consensus conference on medical emergency teams. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2463–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Franklin C, Mathew J. Developing strategies to prevent inhospital cardiac arrest: analyzing responses of physicians and nurses in the hours before the event. Crit Care Med 1994;22:244–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldhill DR, McNarry AF. Physiological abnormalities in early warning scores are related to mortality in adult inpatients. Br J Anaesth 2004;92:882–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harrison GA, Jacques T, McLaws ML et al. . Combinations of early signs of critical illness predict in-hospital death-the SOCCER study (signs of critical conditions and emergency responses). Resuscitation 2006;71:327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hodgetts TJ, Kenward G, Vlackonikolis L et al. . Incidence, location and reasons for avoidable in-hospital cardiac arrest in a district general hospital. Resuscitation 2002;54:115–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jacques T, Harrison GA, McLaws M-L et al. . Signs of critical conditions and emergency responses (SOCCER): a model for predicting adverse events in the inpatient setting. Resuscitation 2006;69:175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buist M, Bernard S, Nguyen TV et al. . Association between clinically abnormal observations and subsequent in-hospital mortality: a prospective study. Resuscitation 2004;62:137–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taenzer AH, Pyke JB, McGrath SP. A review of current and emerging approaches to address failure-to-rescue. Anesthesiology 2011;115:421–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jones DA, DeVita MA, Bellomo R. Rapid-response teams. N Engl J Med 2011;365:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeVita MA, Hillman K, Bellomo R. Textbook of Rapid Response Systems: Concept and Implementation. New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15. DeVita MA, Hillman K, Smith GB. Resuscitation and rapid response systems. Resuscitation 2014;85:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeVita MA, Smith GB, Adam SK et al. . ‘Identifying the hospitalised patient in crisis’—a consensus conference on the afferent limb of Rapid Response Systems. Resuscitation 2010;81:375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hillman KM, Chen J, Jones D. Rapid response systems. Med J Aust 2014;201:519–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shiloh AL, Lominadze G, Gong MN et al. . Early warning/track-and-trigger systems to detect deterioration and improve outcomes in hospitalized patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016;37:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Santiano N, Young L, Hillman K et al. . Analysis of Medical Emergency Team calls comparing subjective to ‘objective’ call criteria. Resuscitation 2009;80:44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hillman KM, Lilford R, Braithwaite J. Patient safety and rapid response systems. Med J Aust 2014;201:654–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Douglas C, Osborne S, Windsor C et al. . Nursing and medical perceptions of a hospital rapid response system: new process but same old game? J Nurs Care Qual 2016;31:E1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chan PS, Jain R, Nallmothu BK et al. . Rapid response teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen J, Ou L, Flabouris A et al. . Impact of a standardized rapid response system on outcomes in a large healthcare jurisdiction. Resuscitation 2016;107:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M et al. . Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:2091–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ludikhuize J, Brunsveld-Reinders AH, Dijkgraaf MGW et al. . Outcomes associated with the nationwide introduction of rapid response systems in The Netherlands. Crit Care Med 2015;43:2544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maharaj R, Raffaele I, Wendon J. Rapid response systems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2015;19:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wendon J, Hodgson C, Bellomo R. Rapid response teams improve outcomes: we are not sure. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:599–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winters BD, Weaver SJ, Pfoh ER et al. . Rapid-response systems as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:417–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maharaj R, Stelfox HT. Rapid response teams improve outcomes: no. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:596–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marshall SD, Kitto S, Shearer W et al. . Why don’t hospital staff activate the rapid response system (RRS)? How frequently is it needed and can the process be improved? Implement Sci 2011;6:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boniatti MM, Azzolini N, Viana MV et al. . Delayed medical emergency team calls and associated outcomes. Crit Care Med 2014;42:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sandroni C, Cavallaro F. Failure of the afferent limb: a persistent problem in rapid response systems. Resuscitation 2011;82:797–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones D. The epidemiology of adult Rapid Response Team patients in Australia. Anaesth Intensive Care 2014;42:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buist MD, Jarmolowski E, Burton PR et al. . Recognising clinical instability in hospital patients before cardiac arrest or unplanned admission to intensive care. A pilot study in a tertiary-care hospital. Med J Aust 1999;171:22–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Daffurn K, Lee A, Hillman KM et al. . Do nurses know when to summon emergency assistance? Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1994;10:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R et al. . Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:251–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones D, Baldwin I, McIntyre T et al. . Nurses’ attitudes to a medical emergency team service in a teaching hospital. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:427–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kitto S, Marshall SD, McMillan SE et al. . Rapid response systems and collective (in)competence: An exploratory analysis of intraprofessional and interprofessional activation factors. J Interprof Care 2015;29:340–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shearer B, Marshall S, Buist MD et al. . What stops hospital clinical staff from following protocols? An analysis of the incidence and factors behind the failure of bedside clinical staff to activate the rapid response system in a multi-campus Australian metropolitan healthcare service. BMJ Qual Safety 2012;21:569–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shapiro SE, Donaldson NE, Scott MB. Rapid response teams seen through the eyes of the nurse. Am J Nurs 2010;110:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee A, Bishop G, Hillman K et al. . The medical emergency team. Anaesth Intensive Care 1995;23:183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Research Checklist 2013 http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf (18 December 2015, date last accessed).

- 44. The Joanna Briggs Institute Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 edition. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G et al. . Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Res Sch 2006;13:29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2006;5:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Astroth KS, Woith WM, Stapleton SJ et al. . Qualitative exploration of nurses’ decisions to activate rapid response teams. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:2876–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bagshaw SM, Mondor EE, Scouten C et al. . A survey of nurses’ beliefs about the medical emergency team system in a Canadian tertiary hospital. Am J Crit Care 2010;19:74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Benin AL, Borgstrom CP, Jenq GY et al. . Defining impact of a rapid response team: qualitative study with nurses, physicians and hospital administrators. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:391–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Braaten JS. Hospital system barriers to rapid response team activation: a cognitive work analysis. Am J Nurs 2015;115:22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Butcher BW, Quist CE, Harrison JD et al. . The effect of a rapid response team on resident perceptions of education and autonomy. J Hosp Med 2015;10:8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cioffi J. Nurses’ experiences of making decisions to call emergency assistance to their patients. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cioffi J. A study of the use of past experiences in clinical decision making in emergency situations. Int J Nurs Stud 2001;38:591–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cretikos MA, Chen J, Hillman KM et al. . The effectiveness of implementation of the medical emergency team (MET) system and factors associated with use during the MERIT study. Crit Care Resusc 2007;9:205–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Davies O, DeVita MA, Ayinla R et al. . Barriers to activation of the rapid response system. Resuscitation 2014;85:1557–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Donohue LA, Endacott R. Track, trigger and teamwork: communication of deterioration in acute medical and surgical wards. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2010;26:10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Green A, Allison W. Staff experiences of an early warning indicator for unstable patients in Australia. Nurs Crit Care 2006;11:118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jenkins SH, Astroth KS, Woith WM. Non-critical-care nurses’ perceptions of facilitators and barriers to rapid response team activation. J Nurses Prof Dev 2015;31:264–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Leach LS, Mayo A, O’Rourke M. How RNs rescue patients: a qualitative study of RNs’ perceived involvement in rapid response teams. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Massey D, Chaboyer W, Aitken L. Nurses’ perceptions of accessing a Medical Emergency Team: a qualitative study. Aus Crit Care 2014;27:133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pantazopoulos I, Tsoni A, Kouskouni E et al. . Factors influencing nurses’ decisions to activate medical emergency teams. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:2668–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pattison N, Eastham E. Critical care outreach referrals: a mixed-method investigative study of outcomes and experiences. Nurs Crit Care 2011;17:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Radeschi G, Urso F, Campagna S et al. . Factors affecting attitudes and barriers to a medical emergency team among nurses and medical doctors: a multi-centre survey. Resuscitation 2015;88:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Robert RR. The Role of Intuition in Nurses Who Activate the Rapid Response Team (RRT) in Medical-Surgical and Telemetry Units. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses,Texas Woman’s University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Salamonson Y, van Heere B, Everett B et al. . Voices from the floor: nurses’ perceptions of the medical emergency team. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2006;22:138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sarani B, Sonnad S, Bergey MR et al. . Resident and RN perceptions of the impact of a medical emergency team on education and patient safety in an academic medical center. Crit Care Med 2009;37:3091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schmid-Mazzoccoli A, Hoffman LA, Wolf GA et al. . The use of medical emergency teams in medical and surgical patients: impact of patient, nurse and organisational characteristics. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:377–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stewart J, Carman M, Spegman A et al. . Evaluation of the effect of the modified early warning system on the nurse-led activation of the rapid response system. J Nurs Care Qual 2014;29:223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tirkkonen J, Yla-Mattila J, Olkkola KT et al. . Factors associated with delayed activation of medical emergency team and excess mortality: an Utstein-style analysis. Resuscitation 2013;84:173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Williams DJ, Newman A, Jones C et al. . Nurses’ perceptions of how rapid response teams affect the nurse, team, and system. J Nurs Care Qual 2011;26:265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wynn JD, Engelke MK, Swanson M. The front line of patient safety: staff nurses and rapid response team calls. Qual Manag Health Care 2009;18:40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Carayon P, Hundt AS, Karsh BT et al. . Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15:i50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ et al. . Human factors systems approach to healthcare quality and patient safety. Appl Ergon 2014;45:14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jones L, King L, Wilson C. A literature review: factors that impact on nurses’ effective use of the Medical Emergency Team (MET). J Clin Nurs 2009;18:3379–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Osborne S, Douglas C, Reid C et al. . The primacy of vital signs – acute care nurses’ and midwives’ use of physical assessment skills: a cross sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:951–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Chua WL, Liaw SY. Assessing beyond vital signs to detect early patient deterioration. Evid Based Nurs 2016;19:53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mackintosh N, Sandall J. Overcoming gendered and professional hierarchies in order to facilitate escalation of care in emergency situations: the role of standardised communication protocols. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1683–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cooper S, Cant R, Sparkes L. Respiratory rate records: the repeated rate? J Clin Nurs 2014;23:1236–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mok W, Wang W, Cooper S et al. . Attitudes towards vital signs monitoring in the detection of clinical deterioration: scale development and survey of ward nurses. Int J Qual Health Care 2015;27:207–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Prgomet M, Cardona-Morrell M, Nicholson M et al. . Vital signs monitoring on general wards: clinical staff perceptions of current practices and the planned introduction of continuous monitoring technology. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. ISMP Canada Understanding human over-reliance on technology. ISMP Canada Saf Bull 2016;16:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Buist M, Mahoney A. In search of the ‘Holy Grail’: will we ever prove the efficacy of Rapid Response Systems (RRS)? Resuscitation 2014;85:1129–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Parmelli E, Flodgren G, Beyer F et al. . The effectiveness of strategies to change organisational culture to improve healthcare performance: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2011;6:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Haas J, Shaffir W. The professionalization of medical students: developing competence and a cloak of competence. Symb Interact 1977;1:71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hall P. Interprofessional teamwork: professional cultures as barriers. J Interprof Care 2005;19:188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bowie P. Leadership and implementing a safety culture. Pract Nurse 2010;40:32. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cioffi J, Conway R, Everist L et al. . ‘Patients of concern’ to nurses in acute care settings: a descriptive study. Aus Crit Care 2009;22:178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Douw G, Huisman-de Waal G, van Zanten ARH et al. . Nurses’ ‘worry’ as predictor of deteriorating surgical ward patients: a prospective cohort study of the Dutch-Early-Nurse-Worry-Indicator-Score. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;59:134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Liew S-L, Ma Y, Han S et al. . Who’s afraid of the boss: cultural differences in social hierarchies modulate self-face recognition in Chinese and Americans. PLoS One 2011;6:e16901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.