Abstract

Chromosomal area 19p13 contains two migraine associated genes: a Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) calcium channel α1 subunit gene, CACNA1A, and an insulin receptor gene, INSR. Missense mutations in CACNA1A cause a rare Mendelian form of migraine, familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 (FHM1). Contribution of CACNA1A locus has also been studied in the common forms of migraine, migraine with (MA) and without aura (MO), but the results have been contradictory. The role of INSR is less well established: A region on 19p13 separate from CACNA1A was recently reported to be a major locus for migraine and subsequently, the INSR gene was associated with MA and MO. Our aim was to clarify the role of these loci in MA families by analyzing 72 multigenerational Finnish MA families, the largest family sample so far. We hypothesized that the potential major contribution of the 19p13 loci should be detected in a family sample of this size, and this was confirmed by simulations. We genotyped eight polymorphic microsatellite markers surrounding the INSR and CACNA1A genes on 757 individuals. Using parametric and non-parametric linkage analysis, none of the studied markers showed any evidence of linkage to MA either under locus homogeneity or heterogeneity. However, marginally positive lod scores were observed in three families, and thus for these families the results remain inconclusive. The overall conclusion is that our study did not provide evidence of a major MA susceptibility region on 19p13 and thus we were not able to replicate the INSR locus finding.

Keywords: INSR, CACNA1A, linkage, migraine with aura

INTRODUCTION

One of the most intriguing regions with involvement in migraine is the chromosome 19p13, which contains two migraine associated genes, INSR and CACNA1A. This region has mostly been associated with a rare Mendelian form of migraine, familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM1), caused by CACNA1A mutations [Ophoff et al., 1996]. However, recently Jones et al. reported that this region and specifically insulin receptor gene (INSR) would be a major locus for common forms of migraine, especially migraine with aura [Jones et al., 2001].

The only true molecular insight into migraine pathophysiology has been provided by the identification of FHM mutations. By contrast, the molecular background of more common forms of migraine, migraine with (MA) and without (MO) aura, has remained largely unresolved. Recently, a number of susceptibility loci has been detected in genome-wide scans, but no underlying variants have been identified [Carlsson et al., 2002; Wessman et al., 2002; Bjornsson et al., 2003; Cader et al., 2003; Soragna et al., 2003]. The involvement of CACNA1A in more common forms of migraine has been suggested, the hypothesis being that the pathophysiology of common and rare forms of migraine shares same cellular pathways. Convincing molecular evidence for this is still missing, but it is encouraging that both CACNA1A encoding the α1 subunit of neuronal Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) calcium channels and the other gene identified to cause FHM, ATP1A2 encoding Na+,K+-ATPase α2 subunit, are involved in ion transport of the cell membrane [De Fusco et al., 2003]. This idea of similar underlying pathophysiology has stimulated a number of studies testing the contribution of CACNA1A (FHM1) locus in both MA and MO. Some of these studies have reported suggestive linkage to the FHM1 locus [May et al., 1995; Nyholt et al., 1998; Terwindt et al., 2001]. Also, several contradictory studies exist where no linkage or association to this locus was found in MA or MO [Hovatta et al., 1994; Lea et al., 2001; Noble-Topham et al., 2002]. In addition, a few groups have reported sequencing either the entire CACNA1A gene or selected areas of it in patients with common forms of migraine but no mutations have been found [Lea et al., 2001; Brugnoni et al., 2002; Wieser et al., 2003].

Based on the evidence reported by Jones et al. [2001], the chromosomal region of 19p13 containing the INSR gene would have a major contribution to migraine susceptibility. According to their data, 13 out of the 16 MA families studied were linked to this region flanked by markers D19S427 and D19S592 [Jones et al., 2001]. Subsequently, they showed that five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the INSR gene were significantly associated with migraine [McCarthy et al., 2001]. These findings should trigger replication studies.

Based on previous studies, the involvement of the chromo-some 19p13 in common forms of migraine remains suggestive with only one study [Jones et al., 2001] suggesting a major contribution of this locus in 16 North-American families. Since in our genome-wide scan [Wessman et al., 2002] one of the several lod scores with a nominal P-value of ≤0.05was observed with marker D19S427 close to the INSR, the contribution of the two chromosome 19p loci in MA was further studied in 72 multigenerational MA families from our Finnish migraine family cohort. We hypothesized that if either the INSR or the CACNA1A locus contributes to MA, this would be detectable in our large sample.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Families

Since 1996, our group has recruited MA families with at least three affected first-degree family members from four Finnish headache clinics (Helsinki, Turku, Jyväskylä, and Kemi) for clinical and molecular genetic studies. Additionally, advertisements in the newsletter of the Finnish Migraine Society were used. Thus, this migraine sample represents families all over Finland rather than a specific subisolate. The recruitment of the families is described in more detail elsewhere [Wessman et al., 2002]. Diagnosis of the index cases and family members were made by one neurologist (MK) according to the IHS criteria [International Headache Society, 1988] on the basis of the validated Finnish Migraine-Specific Questionnaire for Family studies. The questionnaire contains 37 detailed questions about headache and other aspects of migraine with special emphasis on the characteristics of aura [Kallela et al., 2001]. Individuals with incompletely or contradictory filled questionnaires were interviewed by telephone by the same neurologist.

For this study, we selected the most complete 72 independent multigenerational families with a seemingly dominant inheritance pattern. Fifty out of these 72 families were genotyped in the genome-wide linkage analysis demonstrating that MA is linked to chromosome 4q24 [Wessman et al., 2002]. Blood samples from 757 (446 females, 311 males) out of a total of 978 family members were available including 417 individuals with MA and 91 individuals with MO. Table I describes the diagnosis of the 757 genotyped subjects. Most of the DNA samples were received from families with three generations (41 families out of 72). Of the remaining families, one was four-generational, 27 were two-generational, and three one-generational. The ethics committees of the Helsinki University Central Hospital and the University of California, Los Angeles approved this study and an informed consent was obtained from all family members.

TABLE I.

Summary of the Genotyped Individuals From the 72 Pedigrees

| Gender | Trait | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | MO | EQV | HA | NoHa | MD | Total/gender | |

| Male | 116 | 35 | 3 | 13 | 119 | 25 | 311 |

| Female | 301 | 56 | 5 | 10 | 51 | 23 | 446 |

| Total/trait | 417 | 91 | 8 | 23 | 170 | 48 | 757 |

MA, migraine with aura; MO, migraine without aura; EQV, migraine aura without headache; HA, headache; NoHa, no headache; MD, missing diagnosis.

Clinical characteristics of the MA patients.

The aura phase of the affected subjects was dominated by visual symptoms, but also other types of migraine aura were reported. Aura was visual in 381 (91.4%) cases, a speech disturbance in 128 (30.7%), sensory in 150 (36.0%), and motor in 71 (17.0%) cases. Motor aura was of hemiparetic nature in 68 subjects. Visual aura was a scintillating scotoma in 228 (57%), visual field defect in 173 (43.5%), and photopsia in 196 (49.1%) cases. Additional blurring of vision was reported by 182 patients(45.6%). The headache phase was characterized by frequent and disabling attacks. The number of attacks was over 100 in38.4%, 50–100 in 22.3%, 10–50 in 22.3%, 5–10 in 6.5%, and 2–5 in 1.2% of the MA patients. Thirty subjects had repeated attacks but did not state their exact lifetime frequency. Headache phase lasted usually less than 4 hr in 19.2%, 4–72 hr in 74.6%, and more than 72 hr in 5.3% of the subjects. Four patients did not indicate the duration of their attacks. 383 patients could recall accurately the onset of their migraine and in this group the mean age of onset was 14.3 years (SD 7.4). IHS-defined characteristics [International Headache Society, 1988] of the headache are presented in supplementary Table I.

Genotyping

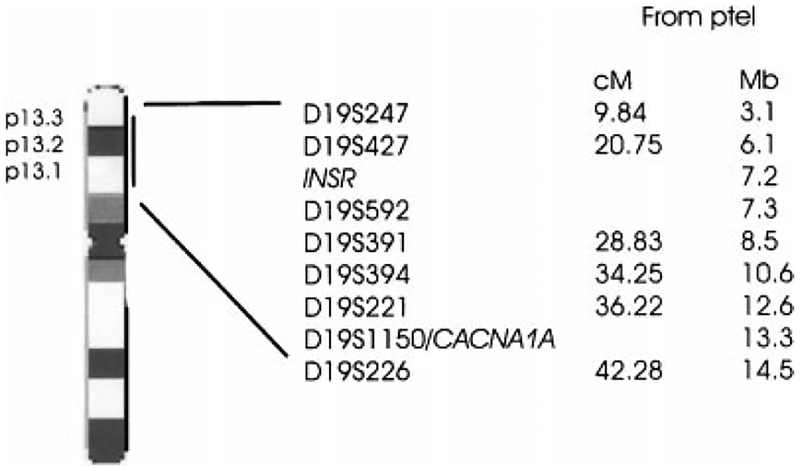

Genotyping was performed on 757 individuals from 72 MA families with eight polymorphic microsatellite markers D19S247, D19S427, D19S592, D19S391, D19S394, D19S221, D19S1150, and D19S226 surrounding the INSR and the CACNA1A genes. Figure 1 shows the locus order and the genetic map distances of the genotyped markers. The PCR fragments, along with a size standard ladder and fragments from known control individuals (CEPH) were analyzed on ABI3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the GeneScan and Genotyper Software (Applied Biosystems). All genotypes were verified by human inspection and reviewed if the PedCheck1.1 [O’Connell and Weeks, 1998] and SimWalk2 2.82 [Sobel and Lange, 1996] computer programs detected genotyping errors. Remaining problematic genotypes were set to unknown.

Fig. 1.

The locus order of genotyped markers and the localization of the INSR and the CACNA1A genes. Information on marker order and genetic map distances was obtained from the UCSC (http://genome.ucsc.edu/, July 2003 release), the Genome Database (http://www.gdb.org), and the Marshfield for Medical Genetics (http://research.marshfieldclinic.org/genetics/) databases. Both the genetic and the physical distance between markers is reported (cM = centiMorgan, Mb = Megabase).

Statistical Analyses

The analyses were performed assuming autosomal dominant inheritance, disease-gene frequency of 0.001, a phenocopy rate of 0.024, and an incomplete penetrance of 0.9 [Wessman et al., 2002]. Allele frequencies were estimated from all genotypes. Only individuals with MA were treated as affected and all other subjects were classified as unknown (affected-only strategy).

Two-point linkage analyses were performed both under locus homogeneity using the MLINK program of the Linkage package [Lathrop and Lalouel, 1984] and allowing for locus admixture using the HOMOG program [Ott, 1991]. In addition, the identity-by-descent (IBD) status of the affected sib-pairs (ASP) was analyzed to investigate the possibility that a putative migraine gene may act in a recessive fashion. Additionally, nonparametric linkage (NPL) analysis was performed using the SimWalk2 version 2.82 [Sobel and Lange, 1996] to investigate the robustness of the results independently of the assumed genetic model. In NPL analysis, the statistical significance of alleles shared IBD between all affected family members is estimated. SimWalk’s statistics B (for dominant traits) and E (NPL_all) were considered.

In order to evaluate how informative the pedigrees are for linkage, simulation studies were used. A marker with five alleles of equal frequency (heterozygosity 0.8) was generated completely linked (θ = 0) to the disease locus. For the simulation study, the disease allele frequency and penetrance model is the same that was used to analyze the data. For each study, a total of 500 replicates was generated using the program SLINK [Ott, 1989; Weeks et al., 1994]. The data was then analyzed using MSIM [Ott, 1989; Weeks et al., 1994] and ELODHET [Ott, 1991], a program that applies the locus admixture test [Ott, 1983; Smith, 1963]. Two measures were evaluated, the expected maximum lod score (EMLOD) and power. The approximation to the EMLOD is the average of the maximum lod scores for each replicate regardless of the theta value at which it occurred. The power, the probability under linkage that the null hypothesis of no linkage will be rejected, is the proportion of replicates where the lod score is equal to or greater than a given threshold (lod 3.0 under linkage homogeneity, lod 3.3 in the presence of linkage admixture) [Terwilliger and Ott, 1994]. In order to determine the power to detect linkage in the presence of admixture, the α (proportion of families linked to the disease locus) was varied from 1.0 to 0.1 in increments of 0.1. In addition, for those families, which produced a lod score >0.59 for at least one of the markers, the EMLOD and maximum lod score were estimated.

RESULTS

Two-Point Linkage Analyses

Two-point linkage analyses were performed in 72 MA families using an affected-only analysis and a narrow affection status criteria by treating only MA patients as affected. The information content of the studied markers varied between 68 and 92% being the highest at D19S394. None of the eight genotyped markers showed any evidence for linkage to the studied 34 cM region surrounding the INSR and the CACNA1A genes on 19p13 either under homogeneity or heterogeneity (Table II). The highest lod score of 0.16 under heterogeneity (HLOD) at a recombination fraction of 0.14 was observed with marker D19S394. The lod scores of the intragenic marker D19S1150 of CACNA1A provided no evidence for linkage in these Finnish MA families (HLOD 0.00). Neither of the INSR flanking markers, D19S427 and D19S592, provided evidence of linkage (HLOD 0.07 and 0.00, respectively). The combined two-point lod scores varied between −26.9 and −46.1 at the recombination fraction (θ) of 0.00 assuming homogeneity (Table II). Furthermore, none of the ASP scores showed evidence of linkage to the genotyped region (Table II). When the affection status was broadened to include also MO (n=91) individuals, the highest lod score was obtained with marker D19S391 (LOD 0.13, θ = 0.46) both under locus homogeneity and heterogeneity.

TABLE II.

Two-Point Lod Scores and NPL Scores for the Eight Studied Markers

| Results under locus homogeneity | Results under locus heterogeneity | NPL_all (SimWalk stat E) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Max lod | θ | Max lod | 0 | Lod scores of ASP analysis | Load at θ = 0.00 | −log (P) | P-value |

| D19S247 | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | – | 0.01 | –45.24 | 0.27 | 0.54 |

| D19S427 | 0.00 | – | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | –26.86 | 0.63 | 0.23 |

| D19S592 | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | – | 0.01 | –38.71 | 0.71 | 0.19 |

| D19S391 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.00 | –39.86 | 0.52 | 0.30 |

| D19S394 | 0.00 | – | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.00 | –43.80 | 0.79 | 0.16 |

| D19S221 | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | –44.38 | 0.36 | 0.44 |

| D19S1150 | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | –44.65 | 0.44 | 0.36 |

| D19S226 | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | – | 0.00 | –46.06 | 0.39 | 0.41 |

Mb, megabase; ASP, affected sib-pair analysis. The two-point lod scores are based on the analysis of individuals with MA.

We carried out a series of simulations of linkage in the 72 families using the SLINK, MSIM, and ELODHET programs. The EMLOD and the power to detect linkage with different values of α are shown in supplementary Figure 1. The results showed that for this data set, it should be possible to detect linkage even when only 30% of the families are linked to the same locus (power = 0.7; EMLOD=4.7). When <30% of the families are linked, the power drops quickly. However, even in the case of only 10% of the families being linked, the EMLOD is still slightly above 1.0, which is clearly higher than the highest maximum lod score achieved in the present study.

The contribution of individual families was also studied by ranking all families according to their lod scores. Figure 3 (see the online Figure 3 at http://www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/0148-7299:1/suppmat/index.html) shows the distribution of individual families’ lod scores for the four markers, D19S427, D19S592, D19S394, and D19S1150 surrounding both the INSR and CACNA1A genes, at a recombination fraction 0.00. The number of families having LOD scores >0.3, >0.5, and >1.0 were 11, 5, and 1 for D19S427, 3, 1, and 0 for D19S592, 5, 5, and 1 for D19S394 and 5, 2, and 0 for D19S1150.

Ten families out of the 72 displayed lod scores at or above 0.59, which is associated with a nominal P-value of 0.05 [Lander and Kruglyak, 1995], in any recombination fraction to at least one of the studied markers (supplementary Table II). The highest lod score for marker D19S427 identifying the INSR region was 1.15 (θ=0) in family number 86. The markers at the CACNA1A region, D19S394, D19S221, D19S1150, and D19S226 showed lod scores of 1.30 (θ=0.05, family 103), 0.96 (θ=0, family 16), 0.59 (θ=0, family 128), and 1.14 (θ=0, family 95), respectively. However, the results of the flanking markers were much lower in all cases (see the online Table IV at http://www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/0148-7299:1/suppmat/index.html). The simulated EMLOD and maximum lod scores for these 10 families are also reported in Table IV. It should be noted that due to the reduced penetrance and phenocopies, the simulated maximum lod scores shown may never be obtained, even in the case where the disease and the marker loci are completely linked and the marker is fully informative. Only one of these families (128) is potentially large enough to establish linkage by itself. This family produces only a slightly positive lod score suggesting that it is probably not linked to this region. Due to the size of the other pedigrees it is difficult to conclude whether the migraine locus segregating in them maps to this region. Yet the finding, that in each family only one marker provided a lod score of >0.59 makes this hypothesis unlikely. When comparing the actual and the simulated results, it can be seen that four out of ten families showed a lod score at or near the simulated maximum. The haplotype segregation in these four families was analyzed and in three families, all MA patients shared a common haplotype within a family.

Non-Parametric Linkage Analysis

We also performed non-parametric linkage analysis with SimWalk2 to exclude the effect of model specification to linkage analysis. The NPL scores did not support linkage (Table II). The statistic B of SimWalk2 showed the highest −log10(P) value of 0.79 (P = 0.16) for marker D19S394.

DISCUSSION

The recently reported MA susceptibility locus on 19p13 [Jones et al., 2001] and the association of migraine with the INSR gene [McCarthy et al., 2001] are intriguing findings that called for replication studies. In the present study, however, the INSR flanking markers D19S427 and D19S592 provided no evidence for linkage (HLOD scores 0.07 and 0.00, respectively) to migraine. Thus we were not able to replicate the nominal linkage to marker D19S427 (1.70, θ=0.22) that was observed in our genome wide screen [Wessman et al., 2002]. Such low lod scores are often false positives and the information provided by the 22 additional families are likely to explain these results. In the present study, the highest individual family lod score for marker D19S592 was 0.57 (θ=0.00). For the other INSR flanking marker, D19S427, a lod of 1.15 (θ=0.00) was observed with family number 86. Simulation studies indicate that this is the highest lod score, which can be obtained for this family. Haplotype analysis showed, that all affected individuals within family 86 shared a common haplotype extending from marker D19S247 to D19S391. Due to the size of the pedigree, it is difficult to conclude whether this single family has a predisposing allele in this region.

We did expect to find at least nominal evidence of linkage to the INSR region considering the very high proportion of linked families (estimated α=0.99) in the study of Jones et al. [2001]. Based on our simulation results, the power of our study to detect linkage is high (power 69%, EMLOD 4.7) even in the case of only 30% of the families being linked. Since the families included in the study of Jones et al. are all North American Caucasians of mainly western or northern European descent [Jones et al., 2001], it seems unlikely that the ethnicity would be the only cause of this discrepancy. It is also worth noting that the IHS criteria for migraine [International Headache Society, 1988] have been used in both cases. Thus gross differences in disease classification are unlikely to explain the discrepancy between our findings and the results by Jones et al. [2001]. Such a discrepancy between loci identified in different study samples is not a rear event in complex traits (e.g. hypertension and schizophrenia [O’Donovan et al., 2003; Mein et al., 2004]). The underlying reasons are not entirely clear but factors like different ascertainment, population origin, and details in diagnostic procedures are likely to contribute to heterogeneity.

Furthermore, our linkage analysis showed no evidence of linkage to D19S1150, the intragenic marker of CACNA1A. The maximum HLOD score was 0.00 and the highest lod score for an individual family (family 128) 0.59 (θ=0). This is in accordance with the previous study on four Finnish MA/MO families [Hovatta et al., 1994] and also with the results of our genome-wide screen [Wessman et al., 2002]. None of our 72 MA families or the 64 Canadian MA families studied by Noble-Topham et al. [2002] showed even suggestive evidence for linkage to the CACNA1A region. In addition, the results of the linkage and association studies performed on 82 Australian MA/MO pedigrees were negative [Lea et al., 2001]. Interestingly, sequencing of CACNA1A in two patients belonging to the only published MA family with suggestive linkage to this region [Nyholt et al., 1998] showed no disease causing mutations [Lea et al., 2001]. Thus, CACNA1A seems not to be a major susceptibility locus for the common forms of migraine in different populations although there still may be high penetrance alleles contributing to the phenotype in selected families. Evidence is also mounting that this locus is not even a minor predisposing locus for migraine but even larger study samples are required to confirm this.

The clinical characteristics of our 72 families are very comparable to the results of a population based study of MA reported by Russell et al. [1996]. There are slightly more sensory and motor auras and slightly less visual auras (90 vs. 99%) in our families compared to Russell’s figures, but overall the similarities clearly outweigh the differences. The fairly large prevalence of hemiparetic and hemisensory symptoms is of note, because based on the present study genes in chromosome 19 are unlikely to cause them.

In conclusion, although several positive findings linking migraine with aura to chromosome 19p13 have been published, we find that in 72 Finnish MA families, the largest data set used so far, neither INSR nor CACNA1A locus shows evidence for linkage to this disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Tanja Moilanen for her expert assistance with contacting the families. We specially thank the Finnish migraine families for their devoted participation to this study.

Grant sponsor: The Helsinki University Central Hospital; Grant sponsor: The Finnish Academy; Grant sponsor: The Sigrid Juselius Foundation; Grant sponsor: The Paulo Foundation; Grant sponsor: The Biomedicum Helsinki Foundation; Grant sponsor: The Finnish Cultural Foundation; Grant sponsor: The Finnish Neurology Foundation; Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (to AP); Grant number: RO1 NS37675–02; Grant sponsor: The Research Foundation of the University of Helsinki (to MAK); Grant sponsor: Helsinki Biomedical Graduate School (to PJT).

REFERENCES

- Björnsson A, Gudmundsson G, Gudfinnsson E, Hrafnsdottir M, Benedikz J, Skuladottir S, Kristjansson K, Frigge ML, Kong A, Stefansson K, Gulcher JR. 2003. Localization of a gene for migraine without aura to chromosome 4q21. Am J Hum Genet 73(5):986–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugnoni R, Leone M, Rigamonti A, Moranduzzo E, Cornelio F, Mantegazza R, Bussone G. 2002. Is the CACNA1A gene involved in familial migraine with aura? Neurol Sci 23(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cader ZM, Noble-Topham S, Dyment DA, Cherny SS, Brown JD, Rice GP, Ebers GC. 2003. Significant linkage to migraine with aura on chromo-some 11q24. Hum Mol Genet 12(19):2511–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Forsgren L, Nylander PO, Hellman U, Forsman-Semb K, Holmgren G, Holmberg D, Holmberg M. 2002. Identification of a susceptibility locus for migraine with and without aura on 6p12.2-p21.1. Neurology 59(11):1804–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fusco M, Marconi R, Silvestri L, Atorino L, Rampoldi L, Morgante L, Ballabio A, Aridon P, Casari G. 2003. Haploinsufficiency of ATP1A2 encoding the Na+/K+ pump alpha2 subunit associated with familial hemiplegic migraine type 2. Nat Genet 33(2):192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovatta I, Kallela M, Färkkilä M, Peltonen L. 1994. Familial migraine: Exclusion of the susceptibility gene from the reported locus of familial hemiplegic migraine on 19p. Genomics 23(3):707–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Headache Society. 1988. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias, and facial pain. Cephalalgia 8(Suppl 7):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KW, Ehm MG, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL, Boyd PR, Peroutka SJ. 2001. Migraine with aura susceptibility locus on chromosome 19p13 is distinct from the familial hemiplegic migraine locus. Genomics 78(3): 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallela M, Wessman M, Färkkilä M. 2001. Validation of a migraine specific questionnaire for use in family studies. Eur J Neurol 8:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E, Kruglyak L. 1995. Genetic dissection of complex traits: Guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet 11(3):241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathrop GM, Lalouel JM. 1984. Easy calculations of lod scores and genetic risks on small computers. Am J Hum Genet 36(2):460–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea RA, Curtain RP, Hutchins C, Brimage PJ, Griffiths LR. 2001. Investigation of the CACNA1A gene as a candidate for typical migraine susceptibility. Am J Med Genet 105(8):707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May A, Ophoff RA, Terwindt GM, Urban C, van Eijk R, Haan J, Diener HC, Lindhout D, Frants RR, Sandkuijl LA, et al. 1995. Familial hemiplegic migraine locus on 19p13 is involved in the common forms of migraine with and without aura. Hum Genet 96(5):604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy LC, Hosford DA, Riley JH, Bird MI, White NJ, Hewett DR, Peroutka SJ, Griffiths LR, Boyd PR, Lea RA, Bhatti SM, Hosking LK, Hood CM, Jones KW, Handley AR, Rallan R, Lewis KF, Yeo AJ, Williams PM, Priest RC, Khan P, Donnelly C, Lumsden SM, O’Sullivan J, See CG, Smart DH, Shaw-Hawkins S, Patel J, Langrish T, Feniuk W, Knowles RG, Thomas M, Libri V, Montgomery DS, Manasco PK, Xu CF, Dykes C, Humphrey PP, Roses AD, Purvis IJ. 2001. Single-nucleotide polymorphism alleles in the insulin receptor gene are associated with typical migraine. Genomics 78:135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mein CA, Caulfield MJ, Dobson RJ, Munroe PB. 2004. Genetics of essential hypertension. Hum Mol Genet 13(1):R169–R175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble-Topham SE, Dyment DA, Cader MZ, Ganapathy R, Brown JD, Rice GP, Ebers GC. 2002. Migraine with aura is not linked to the FHM gene CACNA1A or the chromosomal region, 19p13. Neurology 59(7):1099–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholt D, Lea R, Goadsby P, Brimage P, Griffiths L. 1998. Familial typical migraine. Linkage to chromosome 19p13 and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Neurology 50:1428–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell JR, Weeks DE. 1998. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 63(1): 259–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan MC, Williams NM, Owen MJ. 2003. Recent advances in the genetics of schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet 12(2):R125–R133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ophoff RA, Terwindt GM, Vergouwe MN, van Eijk R, Oefner PJ, Hoffman SM, Lamerdin JE, Mohrenweiser HW, Bulman DE, Ferrari M, Haan J, Lindhout D, van Ommen GJ, Hofker MH, Ferrari MD, Frants RR. 1996. Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Cell 87(3):543–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott J 1983. Linkage analysis and family classification under heterogeneity. Ann Hum Genet 47:311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott J 1989. Computer-simulation methods in human linkage analysis. PNAS 86(11):4175–4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott J 1991. Analysis of human genetic linkage. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Russell MB, Rasmussen BK, Fenger K, Olesen J. 1996. Migraine without aura and migraine with aura are distinct clinical entities: A study of four hundred and eighty-four male and female migraineurs from the general population. Cephalalgia 16:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CAB. 1963. Testing for heterogeneity of recombination fraction values in human genetics. Ann Hum Genet 27:175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel E, Lange K. 1996. Descent graphs in pedigree analysis: Application to haplotyping, location scores, and marker sharing statistics. Am J Hum Genet 58:1323–1337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soragna D, Vettori A, Carraro G, Marchioni E, Vazza G, Bellini S, Tupler R, Savoldi F, Mostacciuolo ML. 2003. A locus for migraine without aura maps on chromosome 14q21.2-q22.3. Am J Hum Genet 72(1):161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger J, Ott J. 1994. Handbook of human linkage. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Terwindt GM, Ophoff RA, van Eijk R, Vergouwe MN, Haan J, Frants RR, Sandkuijl LA, Ferrari MD. 2001. Involvement of the CACNA1A gene containing region on 19p13 in migraine with and without aura. Neurology 56(8):1028–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks DE, Ott J, Lathrop GM. 1994. Slink: A general simulation program for linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 47(Suppl):A204. [Google Scholar]

- Wessman M, Kallela M, Kaunisto MA, Marttila P, Sobel E, Hartiala J, Oswell G, Leal SM, Papp JC, Hämäläinen E, Broas P, Joslyn G, Hovatta I, Hiekkalinna T, Kaprio J, Ott J, Cantor RM, Zwart JA, Ilmavirta M, Havanka H, Färkkilä M, Peltonen L, Palotie A. 2002. A susceptibility locus for migraine with aura, on chromosome 4q24. Am J Hum Genet 70(3):652–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieser T, Mueller C, Evers S, Zierz S, Deufel T. 2003. Absence of known familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM) mutations in the CACNA1A gene in patients with common migraine: Implications for genetic testing. Clin Chem Lab Med 41(3):272–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.