Abstract

In the USA, gay and other men who have sex with men and transgender women are disproportionately affected by HIV. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), anti-retroviral therapy to prevent HIV-negative individuals from seroconverting if exposed to HIV, by members of this population remains low, particularly among African Americans. We conducted two focus groups to assess responses to an online social media campaign focusing on PrEP use in New York City. We designed, produced, and disseminated the campaign to address knowledge of PrEP; physical and psychological side effects; and psychosocial barriers related to PrEP adherence and sex shaming. Focus group participants demonstrated a relatively high knowledge of PrEP, though considerable concerns remained about side effects, particularly among Black participants. Participants suggested that stigma against PrEP users was declining as PrEP use became more common, but stigma remained, particularly for those not using condoms. Many reported distrust of medical providers and were critical of the commodification of HIV prevention by the pharmaceutical industry. Participants reported that those in romantic relationships confronted unique issues regarding PrEP, namely suspicions of infidelity. Finally, Black participants spoke of the need for more tailored and sensitive representations of Black gay men in future programmes and interventions.

Keywords: PrEP, gay men, men who have sex with men, focus groups, social media, USA

Introduction

Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, gay and other men who have sex with men have been disproportionately affected by HIV, accounting for over 67% of new HIV diagnoses in the USA in 2015 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016). Despite this generalised vulnerability, disparities exist within this population; Black men accounted for nearly 39% of new infections among such men and 26% of all new infections in 2015. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates if this trend continues, one in two Black gay and other men who have sex with men will contract HIV in their lifetime. In New York City (NYC), an epicentre of the nation’s HIV epidemic, 2,493 individuals were diagnosed with HIV in 2015; 58% of diagnoses were in gay and other men who have sex with men, and 53% of all men diagnosed were Black or Latino gay or other men who have sex men (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2016). Gay and other men who have sex with men, and transgender women, were the only transmission categories in which HIV diagnoses did not decline between 2001 and 2015.

Given these worrisome statistics, both NYC and New York State have been at the forefront in developing HIV prevention programmes to increase pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness and uptake including large-scale social marketing campaigns, the provision of PrEP and supportive services to the uninsured, and education and outreach to healthcare providers (Scanlin 2016). In New York State, the number of Medicaid recipients receiving PrEP increased from 259 in 2012–2013 to 1,330 in 2014–2015 (Laufer et al. 2015). Additionally, PrEP use reported by gay and other men who have sex with men in an annual NYC behavioural survey increased from 2.1% in 2013 to 14.8% in 2015, although only 12% of those reporting condomless sex were using PrEP (Scanlin 2016). Overall, it is estimated that 2,936 people were prescribed PrEP in NYC in 2015. From 2012–2015, PrEP prescriptions in the USA increased by 738% (Mera 2016).

While PrEP use is increasing, particularly in metropolitan areas like NYC, recent research has shown substantial barriers exist that impact the willingness of gay men and other men who have sex with men, and particularly Black men, to use PrEP. Concerns about medication side effects (Bauermeister et al. 2013; Golub et al. 2013, Smith et al. 2012) and beliefs about PrEP effectiveness (Mutchler et al. 2015; Philbin et al. 2016) and future drug resistance (Golub et al. 2013) have been well documented in the literature. Social factors also contribute to these barriers, including health provider bias (Calabrese et al. 2014), distrust of medical institutions and professionals (Philbin et al. 2016) and unease with the commodification of HIV prevention by the pharmaceutical industry (Young, Flowers and McDaid 2016). Structural factors, such as housing instability (Parket et al. 2016, Philbin et al. 2016) and the intersecting stigmas of HIV and homophobia (Mutchler et al. 2015; Parker et al. 2017; Garcia et al. 2016; Philbin et al. 2016) remain significant barriers, particularly for Black men. Recent scholarship has also called for a focus on social dynamics related to PrEP that extend beyond HIV (Auerbach and Hoppe 2015), including the often-ignored question of sexual pleasure (Race 2016) and the shifting dynamics of risk and safety in an era of biomedical HIV prevention (Koester et al. 2017; Holt 2015).

With current literature pointing to the need for targeted messaging (Mansergh, Koblin and Sullivan 2012; Brooks et al. 2015; Pérez-Figueroa et al. 2015) an online video campaign was developed based on efficacy of a previous video intervention (Chiasson et al. 2009; Hirshfield et al. 2012). Three areas related to PrEP use by gay men and other men who have sex with men and transgender women at risk for HIV were addressed in the campaign: 1) knowledge of PrEP – what it is, how it works, and where you get it; 2) concerns about potential side effects, both physical and psychological, e.g., risk disinhibition; and 3) psychosocial barriers related to PrEP adherence and sex shaming by other gay men and transgender women and those critical of gay and transgender communities.

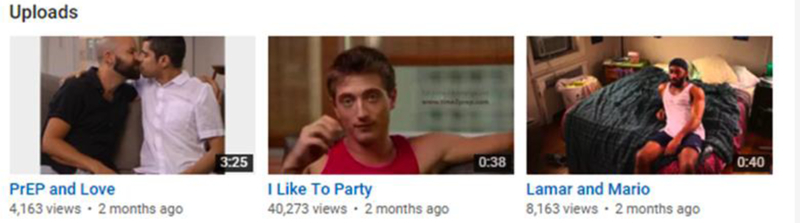

Following stakeholder interviews and focus groups with the target audience, it was decided that three different videos (see Figure 1) would be needed to address the target population’s specific needs. Professional actors and a professional production crew produced the videos. PrEP and Love is short documentary about three HIV serodiscordant couples, two White male couples who use PrEP (Michael Lucas, a well-known adult film maker, is one of the interviewees) and a transgender minority couple with a young child who do not use PrEP. I Like to Party is designed to appeal to men who ‘party & play’ (engage in sexual activities under the influence of recreational drugs) and stars JD Phoenix, a well-known gay, adult film star, who models using PrEP in the video and uses it in real life. WTF is PrEP portrays two Black men who hook up on Grindr and have a brief exchange about PrEP when they meet for sex. The actors in this video, who are members of the community, developed the script. The videos contain links to the campaign website which also houses surveys and links to PrEP educational websites and the NYC PrEP Provider Directory. The campaign was advertised widely on social and sexual networking sites, resulting in over 150,000 views and shares between November 2015 and January 2016 (www.hivbigdeal.org). In this article, we present findings from two focus groups conducted to gain insight into the response to the videos and to participants’ experiences with and perspectives on PrEP generally.

Figure 1:

Screenshot of online social media campaign videos focused on PrEP use in New York City

Methods

Focus group recruitment and consent

Participant recruitment was conducted through advertising at over 200 NYC community-based organisations. An email to organisational staff explained we were recruiting about 20 gay and bisexual men and transgender women to watch videos about PrEP and share their thoughts during a 90-minute focus group. Individuals were eligible if they were a man or transgender woman who reported having sex with men, were at least 18 years old, lived in NYC, and self-reported they had not viewed any of the campaign videos. Individuals interested in participating were asked to complete a short online questionnaire in SurveyGizmo asking age, race, contact information, and borough of residence. These results were used for purposeful sampling. The study co-investigators contacted those who provided their contact information to invite them to a focus group. One focus group included 11 Black gay and other men who have sex with men and one black transgender woman (n=12). The other included five Black, three White, and three Latino gay and other men who have sex with men, and one Latina transwoman (n=12). Participants ranged in age from 21 – 50 and resided in Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx.

Both focus groups were conducted at the Public Health Solutions offices.2 Participants provided written informed consent and were offered a copy of the consent form. Participants could initial or leave a mark rather than signing their names if they preferred for confidentiality. All participants received a $50 incentive and refreshments were provided. All the groups were audio-recorded. Participants were informed that only first names or names of their choice would be used in notes of the discussion, and these names would not be included in any reports or published research.

Focus group protocol

We chose to conduct focus groups because the group dynamic they facilitate allows for social interaction that often generates deeper data than one-on-one interviews (Rabiee 2004). We were interested in understanding the range of perspectives individuals held about PrEP, PrEP users, and the social media campaign, and in-group differences related to these issues. Because focus groups elicit data shaped by the synergy of group interaction (Green, Draper and Dowler 2003), we captured both shared perspectives and divergent opinions on these issues. We decided to conduct one focus group with participants from all ethnic and racial backgrounds and a second with non-White participants only to allow space for further elaboration on PrEP-related issues particular to their communities.

Focus groups were conducted in the following manner. The first and second authors facilitated the focus group and were seated next to one another at one end of the circle. The first author primarily posed questions from the focus group interview guide and probed for elaboration, while the second author took notes pertaining to emerging patterns and interpersonal issues that arose. The second author also asked follow-up questions at the end of the focus group. The third and fourth authors sat behind the circle and took notes.

At the beginning of each focus group the first author posed the following question: ‘What is the first thing that comes to mind when somebody tells you they are on PrEP?’ and asked participants to jot down their responses. This strategy was used, as in other studies (Houser 2004), to avoid ‘groupthink’. This ensured all participants were ‘on the record’ about their attitudes towards PrEP and PrEP users before they were influenced by other participants. Following this question, the first author asked participants about their knowledge of PrEP, their experiences with it and its users, and probed for issues relating to stigma associated with PrEP users and specific interactions with medical providers. Following these initial questions, the participants were shown the videos one by one. After each video, they were asked to provide their reactions and asked about specific themes in each video, such as attributes ascribed to specific characters and specific situations.

Analysis

Focus group transcripts were imported into Dedoose mixed-methods software for analyses and coded deductively and inductively to examine patterns of interest while allowing themes to emerge throughout the analysis. In addition to a code for responses to each video, we began with the following umbrella codes: (1) baseline PrEP knowledge and preliminary attitudes, (2) PrEP barriers, (3) stigma, and (4) experiences talking to providers. Codes were applied to each transcript to identify excerpts representing each key topic, with subcodes developing as new themes emerged from the transcripts. Additionally, new codes emerged, including (1) the role of hook up apps, (2) PrEP side effects, (3) Big Pharma, (4) PrEP as a code for barebacking, and (5) PrEP advertising campaigns. These new codes were applied and analysed in relation to original codes.

The data were password-protected. Only the study team had access. Public Health Solutions and Hunter College Institutional Review Boards approved the study. All names used in the results section are pseudonyms, to protect participant confidentiality.

Results

Preliminary attitudes towards PrEP

Several salient themes emerged from the discussion starter question: What comes to mind when somebody tells you they are on PrEP? First, participants used words like ‘responsible’ and ‘realistic’ to describe a PrEP user, suggesting the user was taking steps to reduce their risk for contracting HIV. This response type was often followed by a caveat regarding the need for the PrEP user to continue to use condoms and the claim that many PrEP users do not realise they are not protected from sexually transmitted infections (STIs). A second typical response was that the PrEP user was motivated by a desire to have bareback sex (condomless anal sex). Participants reporting this kind of initial response to a PrEP user elaborated by saying PrEP users were putting others at risk because they no longer used condoms and often did not understand the importance of adherence. Outlier responses to this opening question included the view that the PrEP user was in a serodiscordant couple and that the PrEP user was HIV-positive.

Misconceptions about PrEP and PrEP marketing

Participants in both focus groups expressed concerns that PrEP users would no longer use condoms. These participants often highlighted that they felt some PrEP users did not fully consider the fact that PrEP did not protect them from STIs. Ryan, a 39-year-old Black gay man explained:

I have concerns with the fact that people feel like it’s ‘not use a condom card’ or something like that and then they decide, ‘Well, I’m on PrEP, I don’t need to use one, you know, I don’t need to take precautions with anything else,’ not thinking about the other things that you could get out there.

In addition to concerns about PrEP users no longer using condoms and thereby heightening their risk for STIs, participants emphasised that they believed that many potential PrEP users were unaware of the medication’s proper use and the need for continued testing. They often linked these misconceptions to shortcomings of PrEP marketing in NYC. Jamie, a 41-year-old gay Latino man said:

People should know all the maintenance testing around it …when you see it on the billboards, when you see it on the side of the bus, it’s like, ‘Hey, take this pill once a day and you avoid HIV.’ And what they don’t talk about is that you will need to be in the doctor’s [office] every quarter getting a STI panel and getting an HIV test.

Participants also reported what they viewed as misconceptions about who should be on PrEP. Rasheed, a 27-year-old gay Black man explained in this way: ‘I’ve heard that it’s only for gay men… I had a conversation with someone today and he told me if he was on PrEP he’d be a whore, like that is his get out of jail free card. Um, so I think that kind of stuff. It’s only for gay men, it’s only for whores.’ Participants suggested widely-held notions about who should be on PrEP were attached to NYC PrEP marketing campaigns targeting gay and bisexual men and transgender women to a greater extent than heterosexuals or other kinds of at-risk groups, such as people who inject drugs.

A few participants felt the social media campaign videos, particularly ‘I Like to Party’, promoted similar misconceptions related to effectiveness and possible side effects. Bernard, a 23-year-old gay Black man objected to the video, saying:

What I don’t like about all these videos and billboards and stuff is that, you know, they don’t put on it that it’s not 100% accurate… most persons don’t see that conditions apply…. So, I think that needs to be up there to let persons know that this is 90% accurate and you still may become infected.

Others felt the videos were subtly condoning bareback sex and argued the videos should have more explicitly promoted condom use alongside PrEP use. After viewing the second video, WTF is PrEP, Rasheed said, ‘If you want people to use condoms and do Truvada the message comes across that he [a character in the video] wanted it raw so it’s almost telling people if you’re on PrEP you don’t need condoms. When it seems like it’s the opposite message you are trying to get across.’

Similar reactions were offered by participants in both focus groups, arguing that PrEP is often used as code for bareback sex, particularly on hook up mobile applications such as Grindr. After watching WTF is PrEP participants had the following conversation.

Jamie: If you find me on an app more than likely I have Neg and on PrEP.

Kyle (a 28-year-old White gay man): I think it’s the way that PrEP has become code for barebacking. And I think that’s what the guy was trying to express.

Voices: True, True

Kyle: He wanted to have condomless sex with that guy. And then the conversation sort of switched gears automatically when the guy was like, ‘what the hell is that?’

Richard (a 30-year-old Latino gay man): Which happens a lot.

Kyle: It was like wink wink.

Richard: He was like, ‘Hey I am on PrEP so if you wanna use a condom it’s okay if not that’s also okay.’ But what I did like was he was empowered. Because when the guy was like ‘what the fuck is that?’ he was like ‘this is not happening. You need to get your information, research and then maybe we can hook up.’

Jamie: I was just going to say that what I got from the interview is what Kyle said. The guy sitting on the bed was throwing out ‘I am on PrEP’ as a code for let’s bareback. Kind of a wink wink.

Bernard: I do think that is true. It’s a code most times for ‘let’s have bareback sex.’ They say I’m on PrEP. 90% of the time it is. And [other participant], I agree with him wholeheartedly. That conversation is held most times on the app or Grindr before you get there. Then it’s time to shag like two lieutenants after lights out.

The commodification of HIV prevention

Participants expressed their mistrust of medical professionals and were critical of what they saw as profit-driven factors behind the push to get gay men to initiate PrEP use. Bernard stated:

It’s always money making, trust me, it’s always about money…I’m sorry but I just think it’s so fishy that you can have PrEP that prevents it or PEP that eradicates it but persons who are positive don’t have that medication to cure themselves. Why? Because there is a market out there for it. If you’re infected, you’re going to need medication.

Caleb, a 50-year-old Black gay man agreed: ‘To answer this young man’s question real quick, the bottom line is that big pharmacy is a business, and treatment is more lucrative than a cure.’

Many felt the push from Big Pharma was more about profit than about reducing HIV incidence and this was particularly concerning because PrEP does not protect from other STIs. Quinn, a 29-year-old Black gay man explained: ‘It’s what the people with the money want. They want to have this falsified reality that everyone is going to be STD-free and just take this pill and it’s gonna be ok. They sitting back in their mansions just having a good ole preppy time.’

Side effects

In both focus groups, participants spoke at length about possible side effects associated with PrEP and emphasised that they felt that healthcare providers and potential PrEP users often do not have enough information about these side effects to make informed decisions about whether or not to recommend or to initiate use. After watching the third video, PrEP and Love, which included some discussion of possible side effects, Rachel, a 34-year-old straight Latina transwoman and a current PrEP user said:

I actually gagged for a second because they were talking about all the side effects and that’s something my doctor didn’t even tell me. I think I shoulda known. I mean I still would have taken PrEP. But they were talking about changes in bone density and the thing is um, as I mentioned before, I am a transgendered person that has had surgery and surgery in and of itself already creates issues with bone density and I have a family history of like osteoporosis... So now, I am like, ‘Oh, I really have to find out all these other side effects.’

A common concern was kidney issues. Eric, a 23-year-old Black gay man, asked: ‘What is this going to do to my body on a daily basis? Do I have to worry about my kidneys stop working?...It’s like a really scary thing to think that because I want to take care of one area of my life I possibly decline in another one.’

Several participants explained that they felt medical providers had inadequate information about possible side effects associated with PrEP. These participants had asked providers about side effects and received what they considered to be inadequate information. They also suggested the video campaign and PrEP advertisement campaigns generally exacerbated this issue. After watching the first video, I Like to Party, the following conversation took place between Jeremiah, a 23-year-old Black gay man; Eric; and Mark, a 25-year-old Black gay man.

Jeremiah: Also, what I didn’t see or hear was, when you watch a commercial for some heart medication, for some reason and then at the end –

Eric: Side effects

Mark: Side effects.

Jeremiah: Like ten-minute spiel, but it’s really in two seconds about like the side effects. I didn’t hear that in there. And somebody who fits this demographic, who likes to party and as you said they go to Chelsea and they do what they gotta do, they gonna see that and they gonna be like, ‘Oh PrEP, I’m getting it.’ But again, they might not ask the question as some of us who have the knowledge, like what does this do. They just go ahead and be like ‘I’m taking it’ but not knowing what it is because the commercial didn’t inform them.

In general, participants saw possible side effects and lack of quality information about those side effects as major barriers to PrEP initiation. Jeremiah said the following of an experience with a provider who encouraged him to take PrEP:

I really had to do my research on my own and go to her with these questions. So like if this is going to F up my kidneys, what is going to happen after that? What are the steps that you guys are doing to help fix these problems…and she was like, ‘Well I really don’t know.’ And once she said that I’m like, ‘You’re the doctor.’ I was like, ‘Okay, forget it. If that’s the case, it’s as simple as that I will use a condom. There is no way that I am going to take it and not know what the real side effects are.’

Side effects and distrust of information received from healthcare providers were more extensively discussed among the focus group comprised of men of colour, and particularly Black men.

Stigma

Stigma was a central theme in both focus groups. Participants cited stigma from both within the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community and outside it. The term ‘Truvada whore’ was discussed on numerous occasions as a kind of backlash against individuals perceived to be taking PrEP so they could engage in bareback sex with multiple partners, though many said this kind of stigma within the community had become less of an issue with time. Still, many participants continued to feel that stigma played a role in whether or not individuals would initiate PrEP. Kyle, a 28-year-old White gay man and a current PrEP user who rejected condom use, joked: ‘Well, I’ve heard, and I am sure people in this room have heard, that people on PrEP are whores and sinners.’ Kyle went on to explain that PrEP users who did not use condoms experienced extra stigma:

It seems to me that listening to the discussion a little bit earlier that there is sort of disingenuousness going on where it’s like we have good will for someone who is on PrEP until we find out that he doesn’t use condoms. Then he goes back to being condemned.

Stigma related to healthcare providers was also discussed. Many participants explained they had either encountered stigma when discussing PrEP with their doctors or they knew individuals who were unlikely to ask for PrEP because of such stigma. Kyle explained:

Kyle: The provider I spoke to on PrEP was a provider I’d never seen in the practice that I go to. So, she was new to me. But I went on a Sunday ‘cuz I was like I just want to get on it. Like right now! Like yesterday! But she was, first of all she didn’t know what it was. And then, secondly, she you know, questioned why I wanted to be gay in the first place. Why I thought that was a healthy choice.

Voices: [murmurs of surprise]

Rachel: 2015?!

Kyle: This was in Manhattan. This was in Harlem…I felt like outraged, you know. Horrified by the experience. But I knew that, I dunno, I don’t mean to flatter myself but I knew about it, I know about PrEP, I knew a lot about it from work. I was like, I am in a position here to like get this because I know how to talk about it and like maybe make a difference in this practice because this is horrible and I know I am not going to be the last gay man who walks through the doors. So, yeah. It didn’t go so well.

While experiences like Kyle’s were outliers, even when participants had positive interactions with their providers, some still felt that they were offered PrEP only because they had sex with men and saw this as a form of stigma. Jim, a 24-year-old Black gay man explained:

She [his provider] said that I should take PrEP and I was like, ‘Uh, I’m ok.’ And she was like, basically, you’re gay and you’re having sex, surely, and active so you should do it…She went on about it and was saying, ‘You’re gay and you’re young, you have a lot of sex you should take PrEP.’ And I’m like, ‘You know, you don’t know me lady.’

A final form of stigma cited by participants was related to PrEP marketing in NYC. Participants consistently said most PrEP advertisements they saw targeted gay men exclusively and took issue with this kind of representation. Eric, the 23-year-old participant who had expressed concern about the impact of PrEP on kidney functioning explained it this way:

I feel a little awkward that PrEP is just marketed to just like the gay community. I feel like if it was more of a general roll out it wouldn’t carry the same stigma. ‘Cuz at the end of the day it’s like ‘all the gays take PrEP.’ It’s kinda like ‘if you’re Black, you like fried chicken.’ It’s just like what the fuck bro, you know? It feels awkward sometimes.

Many participants linked this association between PrEP use and homosexuality back to provider stigma. Damian, a 21-year-old Black bisexual man explained: ‘You walk in and you say, “Hey can I get on PrEP?”, then you might get that squinty eye or that raised eyebrow.’

Relationships and PrEP

The role of PrEP in relationships was another theme that emerged from the focus groups. Victor, a 22-year-old gay Latino man explained that after beginning a new job at an HIV prevention organisation, he was encouraged by co-workers to get on PrEP. He described the experience of discussing PrEP initiation with his own partner, who objected to his beginning PrEP:

I had brought it up to my significant other and he was like, ‘No, you don’t need to get on PrEP.’ You know? So, I am still like in that little, I dunno how to describe it, I am still iffy if I should get on it or if I shouldn’t get on it. Because I also want to listen to what he is saying. Because he doesn’t want to get on it, but I don’t know why he doesn’t want to get on it, you know?

Participants in both groups verified the difficulty monogamous couples experience in discussing PrEP initiation. They most often spoke of jealousy and distrust. Jeremiah explained:

There is a few friends of mine who are negative and they still stuck on the stigma part because they had the conversation, when someone introduces it, it’s crazy when someone introduces it. They’ve had this conversation late night, pillow talk and then it turned into an argument and it’s two o’clock in the morning and they calling me. This is your conversation why you asking me? Basically, folks just on the stigma part because they hear ‘I want to get on PrEP’ and they just like ‘What you out there doing that you need to get on PrEP?’ And then that derails the entire conversation because now they trying to figure out who the other one is fucking.

Need for tailored interventions

A final point that emerged from both focus groups was the importance of tailored messaging around PrEP featuring characters who look like the intended audience. Specifically, many Black and Latino men felt they ‘did not see themselves’ in the first video, I Like to Party, which featured a young White gay man on PrEP. Quinn explained: ‘I think my initial reaction is I wouldn’t relate to that...They don’t even look mixed. And White skin, give something, bring a Latin or a Black brother, I don’t see nothing. It’s like somewhere in Chelsea. Not in Brooklyn where I’m from.’

Other participants felt the I Like to Party video did not represent them, not because of the race of the PrEP user in the video, but because it represented a ‘party boy.’ Rasheed said, ‘When I see this I don’t see me...you [another participant] called that party and play. Like I guess I don’t do that so when I see this I don’t see myself in this. So, this video in particular doesn’t make me want to go and learn more about PrEP.’

Still, other participants felt that even if they did not partake in the kinds of party behaviours of the man featured in the video, they knew many who did and felt the video would be effective amongst this population. Rachel put it most succinctly: ‘He’s in every bar in New York...I know so, so many like him.’

Discussion

Public health officials in New York and across the USA have expanded PrEP access through policy change and tailoring educational measures to vulnerable populations. Despite the recognised potential of and financial investment in PrEP, its uptake has remained low, particularly among those most at risk for HIV. While the CDC estimate that 1,232,000 people have indications for PrEP (Smith et al. 2015), only 79,684 unique individuals were recorded as starting PrEP from 2012–2015 (Mera 2016). Substantial barriers exist impacting the willingness of gay and other men who have sex with men, particularly Black men, to initiate PrEP use. The focus group results presented in this article reflect many of those barriers, including stigma, distrust of medical providers and institutions and the commodification of HIV prevention broadly, concerns about side effects, and the emergent theme of intimate partner characteristics.

Participants cited concerns about negative consequences from bareback sex among PrEP users, a concern highlighted by a recent report of multidrug-resistant HIV infection despite documented adherence to PrEP (Knox et al. 2017). On the other hand, a recent study drawing on narrative accounts of male PrEP users suggests that while PrEP alleviates fears about HIV acquisition, this reduction in fear did not translate into lower condom use among users (Koester et al. 2017). The complexity of this issue was highlighted in both focus groups. Participants expressed admiration for PrEP users for taking control of their sexual health, while continuing to hold stigma against those who stop using condoms after PrEP initiation, as highlighted by Kyle who claimed that PrEP users who does not use condoms ‘go back to being condemned.’

Focus group participants, particularly Black men, expressed a deep mistrust of service providers and were critical of PrEP as part of a larger trend in the commodification of HIV prevention and treatment. Mistrust in novel medical treatments, have historically been greater among Black Americans (Boulware et al. 2003) and mistrust in health institutions due to institutionalised racism has been linked with increased risk of HIV and lower testing rates (Hoyt et al. 2012). A recent study in Scotland focused on how biomedicalisation of HIV prevention impacted individuals’ attitudes towards PrEP found that participants were critical of the commodification of HIV prevention. This was particularly the case among HIV-positive men who were distrustful of Big Pharma and expressed concerns about the impact of PrEP on the accessibility of antiretrovirals for HIV-positive individuals (Young, Flowers and McDaid 2016). Research has shown that misinformation about PrEP and/or lack of awareness of PrEP and its benefits have contributed to this overall mistrust. Focus group participants suggested that PrEP marketing campaigns, including the one developed by our research team, were implicated in such misconceptions. They argued that marketing materials often leave potential users feeling they no longer need to use condoms and that gay and other men who have sex with men and transgender women were overrepresented in these efforts.

Side effects were also cited by focus group participants as a major barrier to PrEP initiation, supporting evidence from recent work, including one study examining potential barriers to PrEP acceptability and adherence among gay and other men who have sex with men and transgender women in NYC that found 78% of participants were concerned with side effects, efficacy, and drug resistance (Golub et al. 2013). The study found Black participants were more likely to cite these concerns than White participants (Golub et al. 2013). Two other recent studies showed a lower likelihood of PrEP use because of side effect concerns (Bauermeister et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2012). Our focus group participants cited concerns with bone density and kidney issues and expressed frustration that providers often cannot answer their questions about side effects and that marketing efforts often do not address them.

Research also shows healthcare providers may be a contributing barrier to gay and other men who have sex with men receiving optimal healthcare and to PrEP initiation (Calabrese et al. 2014). Data on PrEP knowledge among this population in Boston showed that of the 19% who were previously aware of PrEP only 14% had learned about it through medical providers (Mimiaga et al. 2009). A study on physician awareness of their patients’ sexual orientation showed that primary care providers were often not informed of the sexual orientation and practices of their patients in general, Black men fare worse in patient-provider relationships, and White men were more likely to have providers who were aware of their sexual orientation (Petroll and Mosack 2011). Focus group participants suggested that requesting information on PrEP might service lead providers to assume they engaged in same-sex activity. This was particularly a concern for Black participants who confirmed they were not out to their providers.

Current literature on PrEP implementation and interventions shows a consistent theme towards targeted messaging for at-risk groups to address the lack of awareness and negative perceptions and attitudes towards PrEP (Pérez-Figueroa et al. 2015; Brooks et al. 2015; Mansergh, Koblin and Sullivan 2012; Golub et al. 2013). One study to assess the sexual risk trajectories of gay and other men who have sex with men and develop targeted PrEP delivery guidelines identified Black participants as a low-risk group (Pines et al. 2014). Pines et al. suggested that while Black gay and other men who have sex with men were not found to be a high-risk group, characteristics in their sexual networks put them at higher risk for HIV, making the case for messaging specifically targeting social and sexual networks of this population. In effect, Black gay and other men who have sex with men are not just another high-risk group but a complex group with intricacies that need better understanding and further addressing (Eaton et al. 2014; Garcia et al. 2016). Narratives from our focus group participants highlight the complexity related to the ways gay and other men who have sex with men, particularly Black men, are represented in promotional materials, including our social media video campaign. Participants such as Quinn highlighted the need to have promotional materials that reflected individuals who represent the targeted audience, while Eric suggested that the hyper focus on gay men in general for PrEP promotion added to the misconception that ‘all the gays take PrEP.’

This study has some limitations. Because the focus groups were conducted in English and the sample was purposively selected, findings are not generalisable. As the data were collected within focus groups in which participants were asked to express their opinions in front of others, social desirability bias may have affected the results. Furthermore, data were not collected about participants’ socio-economic and educational backgrounds, which might have been contributing factors to responses. We also did not ask participants whether or not they were on PrEP, though two participants disclosed they were currently taking the medication, which also likely shaped their attitudes towards PrEP, its users, and our social media campaign. We also did not collect information on the participants’ HIV status, though one participant disclosed his HIV status during the focus group. As Brisson and Nguyen (2017) have argued, the literature on PrEP has largely focused on its potential and meaning for HIV-negative individuals. Instead, their study focused on HIV-positive men in Paris who suggested that because of their undetectable viral loads, it made little difference to them whether or not their partners were on PrEP. As research moves beyond ‘getting medicine into bodies’ (Auerbach and Hoppe 2015) to address the impact of PrEP on social relationships, future work should incorporate HIV-positive individuals and their perceptions of PrEP and PrEP users.

Despite these limitations, the focus groups provided valuable insight into ongoing barriers to PrEP uptake experienced by transgender women and gay and other men who have sex with men, especially Black men, in NYC. While some progress in reducing new HIV infections has been made (Hall et al. 2017), with an estimated 492,000 gay men and other men who have sex with men in the USA at substantial risk of acquiring HIV (Smith et al. 2015), continuing efforts to refine and target education and prevention activities are essential. The new information about continuing barriers to PrEP initiation – despite efforts made in NYC and across the country – identified through this project will inform future HIV prevention interventions specifically addressing these barriers. In particular, we argue for a ‘social public health’ (Kippax and Stephenson 2012) approach that would take into account potential PrEP users’ concerns and tailor interventions accordingly. Future interventions should consider the complexity of target populations, by using an intersectional approach that accounts for the ways HIV intervention efforts themselves can compound individuals’ and communities’ concerns. To understand and confront the challenges of reaching those most impacted by HIV, research and implementation efforts must embrace the messiness and complexity of social dynamics, rather than hoping biomedical interventions can bypass them.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from Gilead Sciences, Inc. and the National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Disease of the US National Institutes of Health under award number T32AI114398. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institutes of Health or Gilead Sciences, Inc. We would like to thank Dayana Bermudez, Kenny Shults and Roberta Scheinmann for their important contributions to the project.

Footnotes

The first author’s current affiliation is Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Kalamazoo College, Kalamazoo, MI 49007

Public Health Solutions, the largest public health non-governmental organization in New York City, has been working to improve health outcomes in underserved populations since 1957 by providing direct services, research and programme evaluation, and technical assistance.

References

- Auerbach Judith D., and Hoppe Trevor A.. 2015. “Beyond “Getting Drugs Into Bodies”: Social Science Perspectives on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 18 (4 Suppl 3): 19983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister Jose A., Meanley Steven, Pingel Emily, Soler Jorge H., and Harper Gary W.. 2013. “PrEP Awareness and Perceived Barriers among Single Young Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States.” Current HIV Research 11 (7): 520–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebony Boulware L., Cooper Lisa A., Ratner Lloyd E., LaVeist Thomas A., and Powe Neil R.. 2003. “Race and Trust in the Health Care System.” Public Health Reports 118 (4): 358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisson Julien, and Nguyen Vinh-Kim. 2017. “Science, Technology, Power and Sex: PrEP and HIV-positive Gay Men in Paris.” Culture, Health and Sexuality 19 (10): 1066–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks Ronald A., Landovitz Raphael J., Regan Rotrease, Lee Sung-Jae, and Allen Vincent C.. 2015. “Perceptions of and Intentions to Adopt HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in Los Angeles.” International Journal of STD and AIDS 26(14): 1040–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese Sarah K., Earnshaw Valerie A., Underhill Kristen, Hansen Nathan B., and Dovidio John F.. 2014. “The Impact of Patient Race on Clinical Decisions Related to Prescribing HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): Assumptions about Sexual Risk Compensation and Implications for Access.” AIDS & Behavior 18 (2): 226–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. “HIV Among Gay and Bisexual Men.” Accessed September 6, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/.

- Chiasson Mary Ann, Francine Shuchat Shaw Mike Humberstone, Hirshfield Sabina, and Hartel Diana. 2009. “Increased HIV disclosure Three Months after an Online Video Intervention for Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM).” AIDS Care 21 (9): 1081–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton Lisa A., Driffin Daniel D., Smith Harlan, Christopher Conway-Washington Denise White, and Cherry Chauncey. 2014. “Psychosocial Factors Related to Willingness to Use Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men Attending a Community Event.” Sexual Health 11 (3): 244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Jonathan, Parker Caroline, Parker Richard G., Wilson Patrick A., Philbin Morgan, and Hirsch Jennifer S.. 2016. “Psychosocial Implications of Homophobia and HIV Stigma in Social Support Networks: Insights for High-Impact HIV Prevention among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men.” Health Education & Behavior 43 (2): 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub Sarit A., Gamarel Kristi E., Jonathon Rendina H, Anthony Surace, and Lelutiu-Weinberger Corina L.. 2013. “From Efficacy to Effectiveness: Facilitators and Barriers to PrEP Acceptability and Motivations for Adherence among MSM and Transgender Women in New York City.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 27 (4): 248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green Judith, Draper Alizon, and Dowler Elizabeth. 2003. “Short Cuts to Safety: Risk and ‘Rules of Thumb’ in Accounts of Food Choice.” Health, Risk and Society 5 (1): 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hall H. Irene, Ruiguang Song, Tian Tang, Qian An, Joseph Prejean, Patricia Dietz, Hernandez Angela L., Timothy Green, Norma Harris, and Eugene McCray. 2017. “HIV Trends in the United States: Diagnoses and Estimated Incidence.” JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 3 (1): e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfield Sabina, Mary Ann Chiasson Heather Joseph, Scheinmann Roberta, Wayne D Johnson Robert H. Remien, Francine Shuchat Shaw Reed Emmons, Yu Gary, and Margolis Andrew D.. 2012. “An Online Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating HIV Prevention Digital Media Interventions for Men Who Have Sex with Men.” PLoS One 7 (10): e46252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt Martin. 2015. “Configuring the Users of New HIV-Prevention Technologies: The Case of HIV Pre-Exposure prophylaxis.” Culture, Health and Sexuality 17 (4): 428–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser Marian L. 2004. “We Don’t Need the Same Things! Recognizing Differential Expectations of Instructor Communication Behavior for Nontraditional and Traditional Students.” The Journal of Continuing Higher Education 52 (1): 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt Michael A., Rubin Lisa R., Nemeroff Carol J., Lee Joyce, Huebner David M., and Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell. 2012. “HIV/AIDS-Related Institutional Mistrust among Multiethnic Men Who Have Sex with Men: Effects on HIV Testing and Risk Behaviors.” Health Psychology 31 (3): 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippax Susan, and Stephenson Niamh. 2012. “Beyond the Distinction between Biomedical and Social Dimensions of HIV Prevention through the Lens of a Social Public Health.” American Journal of Public Health 102 (5): 789–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox David C., Anderson Peter L., Richard Harrigan P, and Darrell H.S. Tan. 2017. “Multidrug-Resistant HIV-1 Infection Despite Preexposure Prophylaxis.” New England Journal of Medicine 376 (5): 501–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester Kimberly, Amico Rivet K., Gilmore Hailey, Liu Albert, Vanessa McMahan Kenneth Mayer, Hosek Sybil, and Grant Robert. 2017. “Risk, Safety and Sex among Male PrEP Users: Time for a New Understanding.” Culture, Health and Sexuality. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1310927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer Franklin N., O’Connell Daniel A., Ira Feldman, and Zucker Howard A.. 2015. “Vital Signs: Increased Medicaid Prescriptions for Preexposure Prophylaxis against HIV Infection—New York, 2012–2015.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64 (46): 1296–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh Gordon, Koblin Beryl A., and Sullivan Patrick S.. 2012. “Challenges for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States.” PLoS Medicine 9 (8): e1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mera Robertino, McCallister Scott, Palmer Brian, Mayer Gal, Magnuson David, and Rawlings M. Keith. 2016. “FTC/TDF (Truvada) for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Utilization in the United States: 2012−2015.” 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga Matthew J., Case Patricia, Johnson Carey V., Safren Steven A., and Mayer Kenneth H.. 2009. “Preexposure Antiretroviral Prophylaxis Attitudes in High-Risk Boston Area Men Who Report Having Sex with Men: Limited Knowledge and Experience but Potential for Increased Utilization after Education.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 50 (1): 77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler Matt G., Bryce McDavitt Mansur A. Ghani, Nogg Kelsey, Winder Terrell J.A., and Soto Juliana K.. 2015. “Getting PrEPared for HIV Prevention Navigation: Young Black Gay Men Talk About HIV Prevention in the Biomedical Era.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 29 (9): 490–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. “HIV Surveillance Annual Report 2015.” Accessed September 6, 2017. http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/hiv-surveillance-annualreport-2015.pdf.

- Parker Caroline M., Garcia Jonathan, Philbin Morgan M., Wilson Patrick A., Parker Richard G., and Hirsch Jennifer S.. 2017. “Social Risk, Stigma and Space: Key Concepts for Understanding HIV Vulnerability among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in New York City.” Culture, Health and Sexuality 19 (3): 323–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Figueroa Rafael E., Kapadia Farzana, Barton Staci C., Eddy Jessica A., and Halkitis Perry N.. 2015. “Acceptability of PrEP Uptake among Racially/Ethnically Diverse Young Men Who Have Sex with Men: The P18 Study.” AIDS Education & Prevention 27 (2): 112–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroll Andrew E., and Mosack Katie E.. 2011. “Physician Awareness of Sexual Orientation and Preventive Health Recommendations to Men Who Have Sex with Men.” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 38 (1): 63–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbin Morgan M., Parker Caroline M., Parker Richard G., Wilson Patrick A., Garcia Jonathan, and Hirsch Jennifer S.. 2016. “The Promise of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for Black Men Who Have Sex with Men: An Ecological Approach to Attitudes, Beliefs, and Barriers.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 30 (6): 282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines Heather A., Gorbach Pamina M., Weiss Robert E., Shoptaw Steve, Landovitz Raphael J., Javanbakht Marjan, Ostrow David G., Stall Ron D., and Plankey Michael. 2014. “Sexual Risk Trajectories among MSM in the United States: Implications for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Delivery.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 65 (5): 579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiee Fatemeh. 2004. “Focus-Group Interview and Data Analysis.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 63 (4): 655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race Kane. 2016. “Reluctant Objects Sexual Pleasure as a Problem for HIV Biomedical Prevention.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 22 (1): 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlin Kathleen, Mensah Nana P., Salcuni P, Myers Julie E., Daskalakis DC, Edelstein Zoe R. 2016. “Increasing PrEP use among men who have sex with men, New York City, 2013–2015.” Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA, February 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Dawn K., Michelle Van Handel, Richard J Wolitski, Jo Ellen Stryker, Irene Hall H, Joseph Prejean, Koenig Linda J., and Valleroy Linda A.. 2015. “Vital Signs: Estimated Percentages and Numbers of Adults with Indications for Preexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Acquisition—United States, 2015.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64 (46): 1291–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Dawn K., Toledo Lauren, Donna Jo Smith Mary Anne Adams, and Rothenberg Richard. 2012. “Attitudes and Program Preferences of African-American Urban Young Adults about Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP).” AIDS Education and Prevention 24 (5): 408–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young Ingrid, Flowers Paul, and Lisa McDaid. 2016. “Can a Pill Prevent HIV? Negotiating the Biomedicalisation of HIV Prevention.” Sociology of Health and Illness 38 (3): 411–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]