Abstract

β-wrapins are engineered binding proteins stabilizing the β-hairpin conformations of amyloidogenic proteins islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), amyloid-β, and α-synuclein, thus inhibiting their amyloid propensity. Here, we use computational and experimental methods to investigate the molecular recognition of IAPP by β-wrapins. We show that the multi-targeted, IAPP, amyloid-β, and α-synuclein, binding properties of β-wrapins originate mainly from optimized interactions between β-wrapin residues and sets of residues in the three amyloidogenic proteins with similar physicochemical properties. Our results suggest that IAPP is a comparatively promiscuous β-wrapin target, probably due to the low number of charged residues in the IAPP β-hairpin motif. The sub-micromolar affinity of β-wrapin HI18, specifically selected against IAPP, is achieved in part by salt-bridge formation between HI18 residue Glu10 and the IAPP N-terminal residue Lys1, both located in the flexible N-termini of the interacting proteins. Our findings provide insights towards developing novel protein-based single- or multi-targeted therapeutics.

Keywords: Protein aggregation, Intrinsically disordered proteins, α-synuclein, Amyloid-β, Amylin, Molecular dynamics

1. Introduction

Amyloid fibrils are protein aggregates deposited mainly in the extracellular spaces of organs and tissues in diseases such as type II diabetes (Knowles et al., 2014). Pancreatic islet amyloid formed by islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) also referred to as amylin, senile plaques formed by amyloid-β (Aβ), and Lewy bodies formed by α-synuclein (α-syn) are pathological features of type II diabetes (Westermark et al., 2011; Paulsson et al., 2014; Tomita, 2011), Alzheimer’s disease (Huang and Mucke, 2012), and Parkinson’s disease (Lashuel et al., 2013), respectively.

Successful strategies in preventing amyloid fibril formation include, but are not limited to, the sequestration of amyloid monomers, the use of small molecules, the use of peptide-based and protein-(affibody) based inhibitors (reviewed in Härd and Lendel, 2012). Affibody-derived proteins called β-wrapins (β-wrap proteins) can bind, sequester, and thus inhibit amyloid formation by amyloidogenic proteins (Hoyer et al., 2008; Luheshi et al., 2010; Mirecka et al., 2014a,b; Shaykhalishahi et al., 2015). β-wrapins are affibody protein homodimers with a disulfide bond between Cys28 residues connecting the two identical monomer subunits, referred to as subunits 1 and 2 in this study. The scaffold used in engineering β-wrapins is ZAβ3, an Aβ-binding affibody protein that not only prohibits the initial aggregation of Aβ monomers into toxic forms, but also dissociates pre-formed oligomeric aggregates by sequestering and stabilizing a β-hairpin conformation of Aβ monomers (Hoyer et al., 2008; Luheshi et al., 2010; Grönwall et al., 2007).

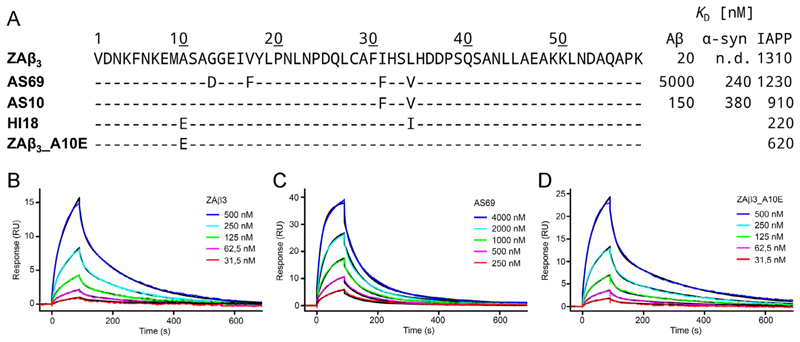

Since the discovery of ZAβ3, a series of β-wrapin variants have been engineered to target Aβ, α-syn, and IAPP using phage-display libraries based on ZAβ3 (Mirecka et al., 2014a,b; Shaykhalishahi et al., 2015; Lindberg et al., 2015; Wahlberg et al., 2017). Previous experiments show that β-wrapin variant AS69 binds significantly stronger to α-syn than to Aβ (Mirecka et al., 2014a; Shaykhalishahi et al., 2015); β-wrapin ZAβ3 binds significantly stronger to Aβ than to α-syn (Shaykhalishahi et al., 2015); β-wrapin AS10 binds Aβ, α-syn, and IAPP with sub-micromolar affinity thereby inhibiting aggregation and toxicity of all three proteins (Shaykhalishahi et al., 2015); β-wrapin HI18 binds IAPP with a dissociation constant of 220 nM (Mirecka et al., 2014b) and was structurally resolved by NMR in complex with IAPP (Mirecka et al., 2016). However, it remains unclear from the NMR structure studies why HI18 is the current most potent β-wrapin for IAPP. Additionally, the potential of β-wrapins ZAβ3 and AS69 to bind and sequester IAPP has not been previously investigated. The sequences of the aforementioned β-wrapin variants and their corresponding dissociation constants for IAPP, Aβ, and α-syn are summarized in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

(A) Sequences of the investigated β-wrapin variants aligned to ZAβ3 and their corresponding dissociation constants for Aβ, α-syn, and IAPP reported here and in Mirecka et al. (2014a), Shaykhalishahi et al. (2015), and Mirecka et al. (2014b). The dissociation constant for ZAβ3 to α-syn was not detected (n.d.). (B, C, and D) Binding of IAPP to ZAβ3, AS69, and ZAβ3_A10E analyzed by SPR. Representative sensorgrams were recorded by injection of ZAβ3 (B), AS69 (C), or ZAβ3_A10E (D) at the indicated concentrations onto a flow cell with immobilized IAPP for 90 s, followed by washing with buffer for 600 s. Global fitting to a two-state interaction model is shown in black, yielding Kd values of 1.31 μM, 1.23 μM, or 620 nM for ZAβ3, AS69, or ZAβ3_A10E, respectively.

The sole inhibition of amyloid formation of IAPP, Aβ, or α-syn may not be a sufficient potential therapeutic strategy for type II diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, or Parkinson’s disease as these proteins promote the formation and/or aggregation of each other (Mittal et al., 2016; Horvath and Wittung-Stafshede, 2016; Roberts et al., 2017). Several studies have solidified the connection between diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease (Moreira, 2013; Crane et al., 2013; Sridhar et al., 2015; Barbagallo and Dominguez, 2014; Oskarsson et al., 2015; Akter et al., 2011; Kroner, 2009; Janson et al., 2004; Zhao and Townsend, 2009; Verdile et al., 2015). Approximately a third of the Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias had a coexisting diabetic medical condition (Alzheimer’s Association, 2015). Growing evidence suggests a possible molecular link between type II diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, thereby increasing the complexity to treat the patients with the aforementioned diseases. A direct molecular link between Alzheimer’s disease and type II diabetes (Oskarsson et al., 2015) is also indicated from dissections of brains from subjects diagnosed with both Alzheimer’s disease and type II diabetes showing that Aβ and IAPP coaggregate (Jackson et al., 2013). Furthermore, IAPP deposits in the brain were found in patients who had suffered from Alzheimer’s disease without clinically apparent type II diabetes (Jackson et al., 2013). Type II diabetes is also associated with a significantly increased risk for developing Parkinson’s disease (Sandyk, 1993; Schernhammer et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2007). The presence of IAPP, both as a monomer and amyloid seed, accelerates the formation of α-syn amyloids (Horvath and Wittung-Stafshede, 2016). This observation may explain why type II diabetes patients are susceptible to developing Parkinson’s disease (Horvath and Wittung-Stafshede, 2016). Simultaneously inhibiting the aggregation of all three of the amyloidogenic proteins can potentially be of critical importance for the treatment of type II diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and/or Parkinson’s disease patients.

The structural elucidation of HI18 in complex with IAPP (Mirecka et al., 2016) provides grounds to investigate a series of β-wrapin variants binding to IAPP, analogously to our previous study that focused on Aβ and α-syn binding (Orr et al., 2016). To provide energetic and structural insight into the inhibition of IAPP amyloid formation by β-wrapins, here we used a combination of computational and experimental methods to investigate the binding of several β-wrapin variants to IAPP. We find that ZAβ3 and AS69, which were originally engineered to target Aβ and α-syn (Grönwall et al., 2007; Mirecka et al., 2014a), respectively, are also capable of binding IAPP with micromolar affinity. Our results reveal the presence of optimized interactions formed between β-wrapin residues and residues in the three amyloidogenic proteins with similar or identical physicochemical properties. We furthermore show that the enhanced affinity of HI18, the currently most potent β-wrapin binder to IAPP, can be attributed in part to predominantly electrostatic interactions between the flexible N-termini of the binding partners.

2. Computational and experimental methods

2.1. Surface plasmon resonance

To enable the elucidation of key determinants of IAPP binding by comparative analysis of β-wrapins, their affinities for IAPP were determined by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The interaction of IAPP with β-wrapins was studied by SPR on a BIAcore T200 (GE Healthcare). Synthetic IAPP, N-terminally modified with biotin and an aminohexanoyl spacer and amidated at the C-terminus (Bachem), was dissolved in 20 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 4.0, and immobilized on a series S sensor chip SA (GE Healthcare) to ~1300 response units (RU). The running buffer was 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.005% (v/v) Tween 20 surfactant. Measurements were performed at a flow rate of 30 μl/min and 25°C. The data were fitted using a two-state 1:1 binding reaction model, consisting of an initial complex formation step with association rate constant ka1 and dissociation rate constant kd1 and a subsequent conformational change in the complex with forward and reverse rate constants ka2 and kd2. The overall equilibrium dissociation constant Kd was calculated using the equation: Kd = kd1*kd2/(ka1(kd2 + ka2)). The signals of an uncoated reference cell and the signals generated by injection of running buffer were subtracted from the sensorgrams.

2.2. Initial computational modeling of simulation systems

Engineered β-wrapins ZAβ3, AS10, AS69, HI18, and ZAβ3_A10E were investigated in complex with IAPP; their corresponding sequences are provided in Fig. 1A. The structure of the HI18:IAPP complex with residues 13 through 56 of both HI18 subunits and residues 10 through 30 of IAPP has recently been resolved (PDB ID: 5K5G Mirecka et al., 2016). For the subsequent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we used the first set of coordinates from the NMR ensemble of structures for the HI18:IAPP complex (Mirecka et al., 2016) as the initial structural template to model all β-wrapins investigated in this study following the methodology of our previous computational study (Orr et al., 2016). While the first set of coordinates is not necessarily the lowest in energy, all 10 sets of coordinates are considered equally valid representatives of the resolved HI18:IAPP complex structure, which is indicated by the low backbone RMSD (0.57 ± 0.08) calculated with respect to the average structure.

MD simulations and MM-GBSA association free energy calculations (described briefly below and detailed in our previous study (Orr et al., 2016)) using a simulation system comprising of residues 12 through 56 of the β-wrapin subunits and residues 10 through 30 of IAPP obtained from the NMR structure of HI18 in complex to IAPP (Mirecka et al., 2016) with residue 12 of both subunits modeled in accordance to Orr et al. (2016) could not sufficiently provide evidence for the improved affinity of HI18 to IAPP in comparison to AS10, which has a dissociation constant approximately 6-fold higher than that of HI18 (Fig. 1A). With respect to AS10, HI18 has 3 mutations: Ala10Glu, Phe31Ile, and Val34Ile; thus we postulated that it is critical to include residue position 10 of β-wrapins in the modeling and simulations. Residues 9 through 12 of subunit 1 of HI18 and residues 1 through 9 of IAPP, which were not experimentally resolved (Mirecka et al., 2016), were modeled using replica exchange MD (REMD) simulations described in the following section; their initial modeling was guided using I-TASSER (Yang et al., 2015). As a result, experimentally unresolved β-wrapin residues in the vicinity of IAPP were included in the modeled system.

2.3. REMD simulations sampling conformations of the unresolved N-terminal domains of IAPP in complex with HI18

We performed four independent REMD simulations (Swendsen and Wang, 1986; Hukushima and Nemoto, 1996; Hansmann, 1997; Sugita and Okamoto, 1999; Sanbonmatsu and Garcia, 2002; Nymeyer et al., 2004) using the structure of HI18:IAPP obtained from I-TASSER (Yang et al., 2015) as the initial structure to model the HI18:IAPP complex. Water was accounted implicitly using the FACTS22 (Haberthür and Caflisch, 2008) solvation model and the simulations were performed using CHARMM (Brooks et al., 2009). The use of the FACTS implicit solvent model in conjunction with REMD simulations has been used in a series of studies to enhance conformational sampling, as well as to model highly flexible regions of protein complexes (Tamamis et al., 2009, 2014a,b; Tamamis and Archontis, 2011; Deidda et al., 2017; Tamamis and Floudas, 2013, 2014a,b; Jonnalagadda et al., 2017). Specifically, Tamamis and Floudas applied an analogous strategy in the modeling of the flexible region of the N-terminal domain of CCR5, at which the experimentally resolved domain was constrained during the simulations (Tamamis and Floudas, 2014b). Similarly, here, to avoid any structural deformation of the experimentally resolved domains of the HI18:IAPP complex, we introduced harmonic constraints of 1.5 kcal/(mol*Å2) on all atoms of residues 11-30 of IAPP, residues 14-56 of subunit 1 of the β-wrapin HI18, and residues 13-56 of subunit 2 of the β-wrapin HI18. The value of the surface tension coefficient in the implicit solvent model was set to 0.015 kcal/(mol*Å2). We used Langevin dynamics using a 5.0 ps−1 friction coefficient for all non-hydrogen atoms. The duration of each replica exchange run was equal to 10 ps, and a total of ten temperatures (287, 294, 300, 307, 314, 321, 329, 337, 345, and 353 K) were employed. The total simulation time for all temperatures per modeled system was equal to 10 ns. We collected the final conformations of each replica exchange run at 300 K per modeled system. These conformations were combined into one trajectory containing conformations from all four of the independent REMD simulations, corresponding to 40 ns and containing 4000 snapshots.

2.4. Principal component analysis and construction of free energy landscapes

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used to investigate the principal motions encountered within MD simulations, through eigenvectors of the mass-weighted covariance matrix (S) of atomic positional fluctuations calculated for the Cα atoms of the system (Amadei et al., 1993; Papaleo et al., 2009; López de Victoria et al., 2012). Here, we superimposed all simulation snapshots produced from the REMD simulations onto the initial structure of the trajectory using Cα atoms only. Subsequently, we focused our analysis on the Cα atoms of the modeled residues that were missing in the NMR studies and conducted a PCA by diagonalizing the covariance matrix S of the Cα atom position deviations with respect to the average structure. The matrix elements for two i and j Cα atoms, Sij, are defined by Eq. (1).

| (1) |

The vector ri denotes the position of atom Cαi, and 〈〉 denotes the time average over the entire trajectory. The diagonalisation of matrix Sij aims at obtaining an orthogonal set of eigenvectors and the eigenvector with large eigenvalues represents the largest concentrated motion of the system. This analysis was conducted with WORDOM (Seeber et al., 2007, 2011).

We constructed a free energy landscape from the REMD simulation snapshots extracted at 300 K, as in López de Victoria et al. (2012), using the projection of the trajectory along the first (PC1) and second (PC2) principal components as reaction coordinates. We divided the (PC1,PC2) subspace into grids and subsequently calculated the two-dimensional probability P(PC1,PC2). Using the two-dimensional probability, the free energy landscape was constructed through Eq. (2).

| (2) |

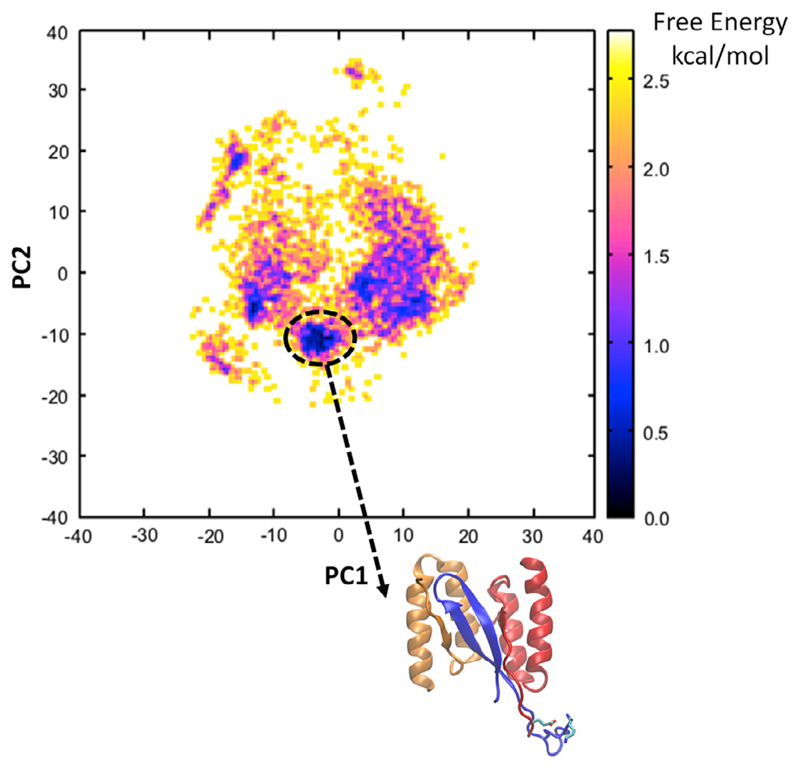

We identified the global free energy minimum basin of the landscape (Fig. 2). We observed that the vast majority of the ensemble of structures within the basin of the global free energy minimum encompass a salt-bridge formed by the subunit 1 Glu10 residue of HI18 with primarily the charged N-terminal end of Lys of IAPP and, in some structures, the side chain group of the same residue. A representative conformation from the free energy landscape in which the negatively charged group of Glu10 of HI18 is at relatively close proximity to both positively charged groups of Lys1 of IAPP is shown at the bottom of Fig. 2. The same structure was used as the initial structural template to model and investigate via MD simulations all the β-wrapin variants in complex with IAPP (see below). To additionally verify that the identified salt-bridge was not an artifact of the selected simulated system and that the salt-bridge would exist even when the truncated β-wrapin termini would be present, we modeled and simulated the entire HI18: IAPP complex following an analogous procedure to Sections 2.2–2.4. The analysis showed that the salt-bridge is reproduced in the vast majority of snapshots modeling the entire complex, and that the β-wrapin residues sequentially prior to Glu10 are highly flexible in line with the NMR studies (Mirecka et al., 2016).

Fig. 2.

Free energy landscape (FEL) constructed from the 2D probability of principal components PC1 and PC2, calculated for the modeled region of the HI18:IAPP complex (residues 9 through 12 of HI18, subunit 1 and residues 1 through 9 of IAPP) derived from REMD simulations at 300 K. The global free energy minimum of the FEL is encircled in a black oval shape. Within the free energy minimum basin, the structures encompass a salt-bridge between subunit 1 residue Glu10 of HI18 with primarily the positively charged N-terminal domain of residues Lys1 of IAPP and, in a few structures, the side chain group of the same IAPP residue. The representative structure which was extracted from the FEL and used as a template and initial structure for the subsequent MD simulations is shown at the bottom of the FEL.

2.5. Molecular dynamics simulations

Six independent 24-ns simulations were performed for each β-wrapin variant in complex with IAPP. The β-wrapin:IAPP complexes were solvated and simulated using the same protocol detailed in Orr et al. (2016). All MD simulations were conducted using CHARMM36 topology and parameters (Best et al., 2012). Each complex was solvated in an 84 Å cubic explicit-water box with a potassium chloride concentration of 0.15 M. Additional potassium ions were introduced to neutralize the charge of the systems. After the solvation-equilibration stage described in Orr et al. (2016), production runs were initiated with simulation snapshots extracted every 20 ps resulting in 1200 snapshots per production run. All solvent molecules were stripped from each simulation trajectory in preparation for subsequent free energy analysis. The MD coordinates of the HI18:IAPP complex, extracted at 12 ns and 24 ns of each of the three replicate MD simulations, are provided in PDB format in the Supplementary Material.

2.6. MM-GBSA association free energy calculations

The association free energy calculations were computed using Molecular Mechanics-Generalized Born/Surface Area (MM-GBSA) (Still et al., 1990; Lazaridis and Versace, 2014) calculations employing the one-trajectory approximation (Gohlke and Case, 2004). In this approximation, the representative coordinates of the bound and free states of the β-wrapin and IAPP are extracted from the β-wrapin:IAPP complex simulation snapshots (Tamamis et al., 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014c; Kieslich et al., 2012; Tamamis and Floudas, 2014a,b; Khoury et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2017). In our previous study, we showed that the total MM-GBSA association free energy can distinguish between active and inactive or minimally active β-wrapins in complex with amyloidogenic proteins Aβ and α-syn, as well as provide a decent correlation with experimentally determined affinities (Orr et al., 2016). In addition, we showed that a significantly low MM-GBSA polar energy component is indicative of a β-wrapin’s high activity (Orr et al., 2016). Here, we used MM-GBSA association free energy calculations to predict the ability of β-wrapins to bind and sequester IAPP. The reported average and standard deviation MM-GBSA association free energy values (Table 1) for each complex were calculated on the basis of the average association free energies calculated from the six independent simulation runs of each complex. Snapshots for these calculations were extracted in increments of 20 ps from each of the simulation runs. In line with our previous study (Orr et al., 2016), we have decomposed the total MM-GBSA association free energies into nonpolar and polar components. Additional details on how the MM-GBSA association free energy calculations were performed are provided in Orr et al. (2016).

Table 1.

Average MM-GBSA association free energies (kcal/mol) decomposed into nonpolar and polar components for β-wrapin:IAPP complexes.

| HI18 | AS10 | AS69 | ZAβ3 | ZAβ3_A10E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | −201.7 ± 5.2 | −183.5 ± 5.0 | −188.2 ± 3.0 | −180.4 ± 5.9 | −189.7 ± 2.5 |

| Nonpolar component | −170.1 ± 1.7 | −169.1 ± 6.2 | −170.0 ± 4.6 | −164.4 ± 9.4 | −163.3 ± 2.1 |

| Polar component | −31.6 ± 4.2 | −14.4 ± 4.9 | −18.1 ± 2.9 | −16.1 ± 6.0 | −26.4 ± 2.5 |

Average MM-GBSA association free energies of β-wrapin:IAPP complexes. The total association free energies are decomposed into nonpolar and polar components. The energy values were determined using Eqs. (3) and (4) of our previous study (Orr et al., 2016).

2.7. Residue pairwise interaction free energy analysis

The residue pairwise interaction free energies for each β-wrapin:IAPP complex production run were calculated for the full length of the 24 ns simulation in increments of 200 ps using CHARMM (Brooks et al., 2009), Wordom (Seeber et al., 2007, 2011), and in-house FORTRAN programs. The standard deviation value for each pairwise interaction in each β-wrapin:IAPP complex was calculated on the basis of the average corresponding interaction free energy values from the six independent simulation runs. Residue pairwise interaction free energy calculations were performed for β-wrapin subunit 1:IAPP, β-wrapin subunit 2:IAPP, β-wrapin subunit 1:β-wrapin subunit 2, β-wrapin subunit 1:β-wrapin subunit 1, and β-wrapin subunit 2:β-wrapin subunit 2 interactions, and are discussed in different sections in the Results. Covalently bonded residue pairs were neglected in these calculations. Additional information on how the residue pairwise interaction free energy calculations were performed is provided in Orr et al. (2016).

2.8. Determination of corresponding residues using a structural-based sequence alignment of β-wrapins’ binding to IAPP, Aβ, and α-syn

To determine pairwise interactions between corresponding residues across all β-wrapin:IAPP/Aβ/α-syn complexes we projected the pairwise interaction free energies in accordance with structure-based sequence alignment of the bound IAPP to the bound Aβ and bound α-syn as shown below:

The structure-based sequence alignment was determined by superimposing the AS10:Aβ/α-syn/IAPP complexes’ backbone atoms using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) (Humphrey et al., 1996; Eargle et al., 2006) and was also validated via the residue pairwise interaction free energies in accordance with our previous study (Orr et al., 2016).

2.9. Identification of potential β-wrapin:IAPP and β-wrapin:β-wrapin interactions acting as switches diminishing β-wrapin affinity (activity) for IAPP

Using AS10 as a basis, we independently calculated the polar and nonpolar residue pairwise interaction free energy differences of HI18:IAPP, AS69:IAPP, and ZAβ3:IAPP residue pairs with respect to the AS10:IAPP complex using Eq. (3).

In Eq. (3), for residue pairwise interactions between subunit 1 of the β-wrapins and the amyloidogenic proteins, R corresponds to a given residue in subunit 1 of the β-wrapins and R′ corresponds to a given residue of the IAPP monomer; for interactions between subunit 2 of the β-wrapins and the amyloidogenic proteins, R corresponds to a given residue in subunit 2 of the β-wrapins and R′ corresponds to a given residue of the IAPP monomer. For interactions between subunits 1 and 2 of the β-wrapins, R refers to a given residue in subunit 1 and R′ corresponds to a given residue in subunit 2; for interactions between residues within subunit 1 of the β-wrapins, R refers to a given residue in subunit 1 and R′ refers to a given residue in subunit 1; for interactions between residues within subunit 2 of the β-wrapins, R refers to a given residue in subunit 2 and R′ refers to a given residue in subunit 2.

| (3) |

Polar or nonpolar interactions acting as potential switches diminishing the activity of a β-wrapin for IAPP are expected to possess unfavorable, or negative, ΔΔG interaction free energy values with respect to AS10, which was used as a basis as it is an active β-wrapin for IAPP. All such interactions identified have large corresponding standard deviation values, denoting that they are not reproducible across the multiple MD simulation runs.

3. Results and discussion

We employed a combination of computational and experimental methods to investigate the binding of engineered β-wrapins ZAβ3, ZAβ3_A10E, AS10, AS69, and HI18 to IAPP, where ZAβ3_A10E is a new β-wrapin variant introduced in this paper for validation purposes.

3.1. Affinity of β-wrapins for IAPP

To enable the elucidation of key determinants of IAPP binding by comparative analysis of β-wrapins, their affinities for IAPP were determined by SPR. ZAβ3 and AS69, which were originally engineered to sequester Aβ and α-syn (Grönwall et al., 2007; Mirecka et al., 2014a), bound to IAPP with Kd values of 1.31 μM and 1.23 μM, respectively (Fig. 1B and C). These values are comparable to the Kd value of AS10, which is 0.910 μM (Shaykhalishahi et al., 2015), and ~6-fold higher than the Kd value of HI18, which was specifically selected to bind IAPP (Mirecka et al., 2014b). Unlike Aβ and α-syn, IAPP does not exhibit a major affinity loss to any of the investigated β-wrapins (Fig. 1A), suggesting that it is a comparatively promiscuous β-wrapin target.

3.2. Modeling of the β-wrapin:IAPP complex

MD simulations were introduced to investigate the binding of β-wrapins HI18, AS10, ZAβ3, and AS69 to IAPP at an atomistic level. With respect to AS10, HI18 has 3 mutations: Ala10Glu, Phe31Ile, and Val34Ile. The Ala10Glu mutation is not resolved in the NMR structure of the HI18:IAPP complex due to absence of NOEs in this region, in line with increased flexibility of the N-terminal segments of both interacting proteins (Mirecka et al., 2016). Initially, we performed MD simulations and free energy calculations using the first set of coordinates from the NMR ensemble of HI18:IAPP complex structures (PDB ID: 5K5G Mirecka et al., 2016), which excludes the experimentally unresolved β-wrapin residue position 10. The energetic analysis of these simulations suggested that the inclusion of additional experimentally unresolved residues is important to computationally provide evidence for the improved affinity of HI18 to IAPP in comparison to the other investigated β-wrapins.

The initial modeling of additional residues was performed using REMD simulations. Upon the completion of the REMD simulations, we collected the conformations at 300 K, and constructed a free energy landscape (Fig. 2) using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), as in López de Victoria el al. (2012). In the vast majority of the structures within the global free energy minimum, the modeled Glu10 residue of HI18 subunit 1 forms a salt-bridge with primarily the charged N-terminal of residue Lys1 of IAPP and, in a few structures, with the positively charged ε-amino group in the side chain of the same residue. From the global free energy minimum, we extracted a representative structure of the HI18:IAPP complex structure. The structure was selected on the basis that the negatively charged group of HI18 subunit 1 residue Glu10 forms a salt-bridge with the positively charged N-terminal of IAPP and is concurrently in close proximity to the charged side chain ε-amino group of IAPP residue Lys1. The selected hybrid, NMR-based and computationally modeled, structure of HI18 in complex with IAPP was used as an initial conformation in the subsequent MD simulations and MM-GBSA association free energy calculations using CHARMM (Brooks et al., 2009), through which we aimed to investigate the structural and energetic properties of β-wrapins HI18, AS10, AS69, and ZAβ3 in complex with IAPP.

3.3. MM-GBSA association free energy calculations of the β-wrapin: IAPP complexes

Analogously to our previous studies (Orr et al., 2016), here, we used the single trajectory MM-GBSA approximation (Gohlke and Case, 2004) to calculate the association free energy of the β-wrapin:IAPP complexes and assess the computational modeling of the complexes. The calculated MM-GBSA association free energies were used as an assessment of the β-wrapins’ relative rather than absolute affinities for IAPP. Their systematically large magnitudes stem from the combination of the approximations of the continuum solvation model (Gohlke and Case, 2004; Kongsted et al., 2009; Genheden and Ryde, 2010) and the omission of the entropic effect due to structural relaxation. The resulting average MM-GBSA association free energies of the β-wrapin:IAPP complexes are decomposed into polar and non-polar components in Table 1. The MM-GBSA analysis shows that β-wrapins AS10, ZAβ3, and AS69 in complex with IAPP have similar MM-GBSA association free energy values and that the HI18:IAPP complex acquires the lowest MM-GBSA association free energy. Furthermore, the HI18:IAPP complex also acquires the lowest polar association free energy component of all investigated β-wrapin:IAPP complexes, suggesting that HI18 should be a highly active β-wrapin for IAPP. These results are in line with the SPR data depicting that AS10, ZAβ3, and AS69 bind IAPP with similar affinity while HI18 exhibits increased affinity. The agreement of the computational results with current and previous experiments (Mirecka et al., 2014b; Shaykhalishahi et al., 2015) supports the validity of the computational methods introduced here to study β-wrapins in complex with IAPP, and suggests that computational methods can be introduced in future studies for the design of novel highly active β-wrapins.

3.4. Interactions contributing to enhanced binding between HI18 and IAPP

The MD simulation snapshots of the HI18:IAPP complex were investigated to determine the key interactions contributing to the enhanced binding affinity of HI18 for IAPP through structural analysis and free energy calculations. To obtain additional insights into the binding of HI18 to IAPP, residue pairwise interaction free energy calculations were performed; the resulting maps corresponding to the residue pairwise interaction free energies decomposed into polar and nonpolar components between subunit 1:IAPP, subunit 2:IAPP, and subunit 1:subunit 2 of the HI18:IAPP complex are presented in Fig. S1.

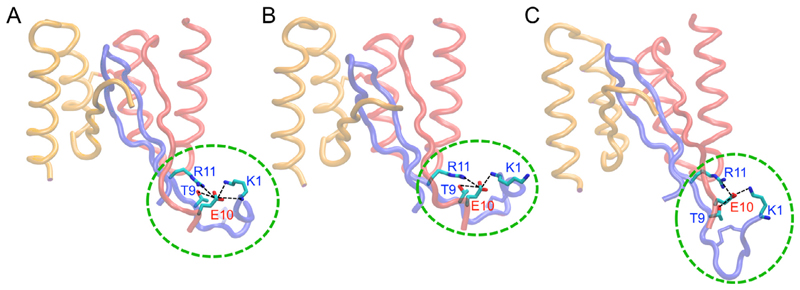

Within the simulations of the HI18:IAPP complex, the Ala10Glu mutation which is present in HI18 but not in AS10, AS69, and ZAβ3, allows for the preservation of the salt-bridge between the positively charged N-terminal of IAPP and the negatively charged group of Glu10 of HI18 subunit 1 observed in the initial structure of the HI18:IAPP throughout all MD simulations. Aside from the aforementioned salt-bridge, Glu10 of subunit 1 in HI18 alternatively forms a salt-bridge with the charged side chain groups of Lys1 or Arg11 in IAPP within the simulation trajectories. The Ala10Glu mutation in HI18 moreover contributes to the formation of a hydrogen bond between the side chain carboxyl groups of Glu10 in subunit 1 of HI18 with the hydroxyl group of Thr9 in IAPP. These interactions, which enhance the binding of HI18 to IAPP, are prevalent throughout the duration of the MD simulations and are presented in Fig. 3.

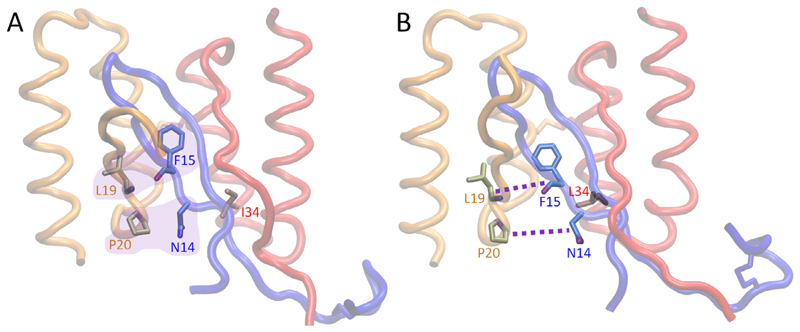

Fig. 3.

Molecular graphics images of HI18 in complex with IAPP. (A,B,C) Snapshots extracted from the MD simulations illustrating the increased mobility of the N-termini in comparison to the core of the complex. Glu10 of subunit 1 in HI18 forms salt-bridges with Lys1 and Arg11 of IAPP as well as hydrogen bonds with Thr9 of IAPP. The flexible N-termini are encircled with green dotted lines. Interactions between Glu10 of subunit 1 in HI18 and the N-terminus of IAPP remain prevalent throughout the MD simulations. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

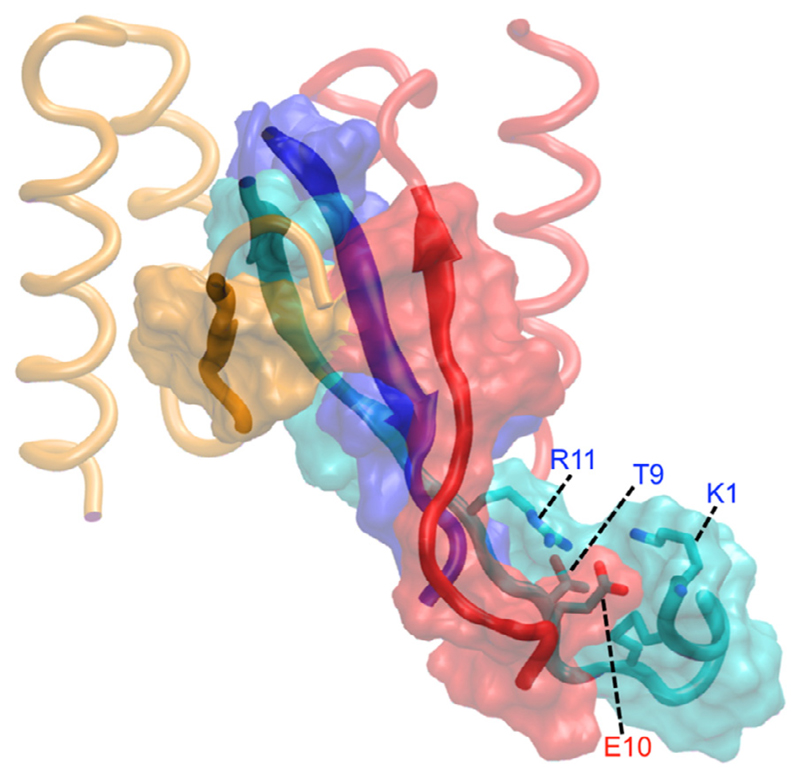

The strong polar interactions between Glu10 in subunit 1 of HI18 and Lys1, Thr9, and Arg11 of IAPP also facilitate the formation of nonpolar interactions between the N-terminal ends of IAPP and subunit 1 of HI18 (Fig. S1A) and extend the hydrophobic surface of the antiparallel β-sheet that constitutes the core of complex (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, the interacting N-terminal regions remain more flexible than the complex core, with a backbone RMSD of the entire trajectories with respect to the average structure of 4.6 ± 1.7 Å for the N-terminal regions, compared to 1.5 ± 0.4 Å for the NMR-resolved complex core (Fig. 3). The increased flexibility of the interacting N-terminal regions can explain the absence of NOEs in these regions in NMR spectroscopy.

Fig. 4.

Molecular graphics images of HI18 in complex with IAPP. Polar interactions between the flexible N-termini enhance nonpolar interactions between IAPP and HI18, extending the hydrophobic surface shown in orange (β-wrapin subunit 1), red (β-wrapin subunit 2), cyan and blue (IAPP) surface representation, of the antiparallel β-sheet in the structure. β-Wrapin subunits 1 and 2 are shown in red and orange tube representation, respectively, and IAPP is shown in cyan and blue tube representation. Red and blue labels indicate residues of subunit 1 of the β-wrapin and IAPP, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We generated the ZAβ3 mutant ZAβ3_A10E carrying only the Ala10Glu exchange to further validate the computational modeling of the β-wrapin:IAPP complexes, with emphasis on validating the salt-bridge formed between HI18 subunit 1 residue Glu10 with Lys1 of IAPP. We note that this sequence was among those identified in the original phase display selection of IAPP-binding β-wrapins (Mirecka et al., 2014a,b). In SPR, ZAβ3_A10E exhibited enhanced binding affinity to IAPP compared to ZAβ3 and a reduced binding affinity compared to HI18 (Fig. 1D). The improved affinity of ZAβ3_A10E compared to ZAβ3, AS10, and AS69 can be attributed to its capacity to form a salt-bridge with Lys1 of IAPP. The lower affinity of ZAβ3_A10E compared to HI18 provides evidence for a role of the Leu34Ile exchange in promoting IAPP binding. In agreement with the SPR data, the MM-GBSA association free energy of ZAβ3_A10E is higher than that of HI18, but lower than those of the other investigated β-wrapins, which supports the validity of the computational modeling (Table 1). According to visual inspection (Fig. 5), residue Leu34 of ZAβ3_A10E contributes allosterically to a weakening of the β-wrapin binding to IAPP compared to residue Ile34 of HI18. During the simulations Leu34 faces toward the interior of the core of the β-wrapin:IAPP complex and increases residue crowding. This results in the weakening of the hydrogen bond interaction between the carboxyl oxygen of Phe15 in IAPP and the backbone nitrogen of Leu19 in subunit 2 of HI18, as well as the nonpolar interaction between Asn14 in IAPP and Pro20 in subunit 2 of HI18 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Molecular graphics images of (A) HI18 and (B) ZAβ3_A10E in complex with IAPP. These two β-wrapins only differ at residue position 34, which is Ile in HI18 and Leu in ZAβ3_A10E. (A) Favorable interactions occurring in the HI18:IAPP complex are encapsulated in purple. (B) Weakened interactions occurring in the ZAβ3_A10E: IAPP complex are indicated with purple dotted lines between the two interacting residue pairs. β-Wrapin subunits 1 and 2 are shown in red and orange tube representation, respectively, and IAPP is shown in blue tube representation. Red, orange, and blue labels indicate residues of subunit 1 of the β-wrapin, subunit 2 of the β-wrapin, and IAPP, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.5. Commonalities contributing to the multi-targeted binding of amyloidogenic proteins by β-wrapin AS10

AS10 is a multi-target β-wrapin, recognizing IAPP, Aβ, and α-syn with sub-micromolar affinity (Shaykhalishahi et al., 2015). According to our previous study, the ability of AS10 to bind and sequester both Aβ and α-syn stems from common pair-wise interactions between AS10 and corresponding residues of Aβ and α-syn that are physicochemically similar and align upon structural superposition of the AS10:Aβ and AS10:α-syn complexes (Orr et al., 2016). For the purpose of the current study, we expand our analysis on interactions of AS10 with corresponding residues of IAPP, identified by structural superposition of the AS10 complexes of IAPP, Aβ, and α-syn.

To investigate the multi-target binding properties of AS10, we calculated the interaction free energies between the residue pairs, referred to as pairwise interaction free energies, for the AS10:IAPP complex and compared the interaction free energy values to those of the AS10:Aβ/α-syn complex (Orr et al., 2016). The average residue pairwise intermolecular interaction free energies between subunit 1:IAPP, subunit 2:IAPP, and subunit 1:subunit 2 occurring in the AS10:IAPP complex were decomposed into polar and nonpolar contributions and are mapped in Fig. S2. Upon completion of the calculations, we compared the binding properties of the AS10:IAPP complex to the AS10:Aβ and AS10:α-syn complexes by projecting the average residue pair-wise interaction free energy values of the AS10:IAPP complex onto the corresponding AS10:Aβ/α-syn complex residue pair-wise interaction free energies (Orr et al., 2016) to uncover the key commonalities in AS10 binding to the three amyloidogenic proteins.

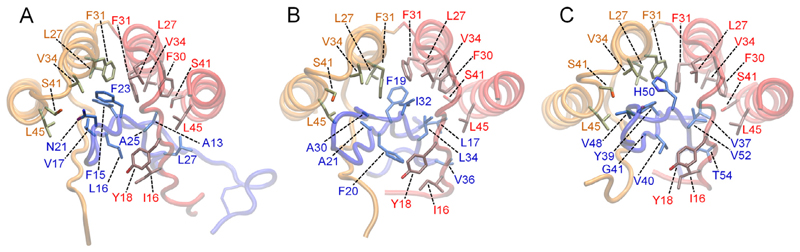

The analysis, in conjunction with the analysis performed by us in Orr et al. (2016), highlights important contributions of interactions between certain AS10 residues and specific Aβ/α-syn/IAPP residues. The residue moieties 15EIVYL19 of AS10 subunits 1 and 2 interact with two amyloidogenic fragments of IAPP, 14NFLVHSS20 (Gilead and Gazit, 2008) and 22NFGAIL27 (Tenidis et al., 2000) by forming an antiparallel β-sheet. This is in analogy to the complexes AS10:Aβ (amyloidogenic strands 16KLVFFAE22 (Tao et al., 2011) and 30AIIGLMV36 (Cheng et al., 2012)) and AS10:α-syn (amyloidogenic strands 36GVLYVGS42 and 51GVATVA56 (Teng and Eisenberg, 2009)) (Orr et al., 2016). Nonpolar interactions between pairs of AS10 and Aβ/α-syn/IAPP residues critically contribute to the multi-target binding properties of AS10. These important nonpolar interactions are summarized in Table 2. The common network of nonpolar interactions in the AS10:IAPP complex, AS10:Aβ complex, and AS10:α-syn complex are shown in Fig. 6A, B, and C, respectively.

Table 2.

Key nonpolar interactions between AS10 subunit residues and corresponding residues of the amyloidogenic proteins contributing to multi-target binding of AS10.

| AS10 residue (subunit 1) | IAPP residue | Aβ residue | α-syn residue |

| Ile16 | Leu16 | Phe20 | Val40 |

| Tyr18 | Leu16 | Phe20 | Val40 |

| Leu27 | Phe23 | Ile32 | His50 |

| Phe30 | Ala25 | Leu34 | Val52 |

| Phe31 | Ala25 | Leu34 | Val52 |

| Phe31 | Phe15 | Phe19 | Tyr39 |

| Val34 | Ala13 | Leu17 | Val37 |

| Ser41 | Ala13 | Leu17 | Val37 |

| Leu45 | Ala13 | Leu17 | Val37 |

| Leu45 | Ala25 | Leu34 | Val52 |

| Leu45 | Leu27 | Val36 | Thr54 |

| AS10 residue (subunit 2) | |||

| Leu27 | Phe15 | Phe19 | Tyr39 |

| Phe31 | Phe23 | Ile32 | His50 |

| Val34 | Asn21 | Ala30 | Val48 |

| Leu45 | Val17 | Ala21 | Gly41 |

Fig. 6.

Molecular graphics images of the common hydrophobic interactions of AS10 in complex with IAPP (panel A), Aβ (panel B), and α-syn (panel C). AS10 subunits 1 and 2 are shown in red and orange tube representation, respectively, and IAPP is shown in blue tube representation. The specified hydrophobic and aromatic interactions contribute significantly to the ability of AS10 to sequester all three of the amyloidogenic proteins. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The polar interactions between AS10 subunits 1 or 2 and amyloidogenic protein residues outside the β-sheet cores correspond with hydrogen bonding and are more specific compared to nonpolar contacts. A portion of these polar interactions involve AS10 subunit 1,2:corresponding amyloidogenic proteins’ (Aβ/α-syn/IAPP) residue pairs. These interactions are summarized in Table 3. Additionally, the salt-bridge formed between Glu15 of subunit 1 in AS10 and Arg11 of IAPP may enhance the binding properties of AS10 (as well as all other β-wrapins investigated in this study) to IAPP.

Table 3.

Polar interactions between AS10 and corresponding amyloidogenic protein contributing to multi-targeted properties.

| AS10 residue (subunit 1) | IAPP residue | Aβ residue | α-syn residue |

| Y18 OH | H18 ND1/NE2 | E22 OD1/OD2 | S42 OH |

| S41 OH | R11/L12/A13 backbone carboxyl/amide groups | E35/G36 backbone carboxyl/amide groups | |

| AS10 residue (subunit 2) | |||

| S41 OH | N21 backbone carboxyl/amide groups | G47/V48 backbone carboxyl/amide groups | N27/G29 backbone carboxyl/amide groups |

3.6. Intra-subunit interactions stabilizing β-wrapin subunit structure

We investigated intramolecular subunit residue interactions (i.e., subunit 1:subunit 1 residue interactions, and subunit 2:subunit 2 residue interactions) occurring in all β-wrapin:IAPP complexes using interaction free energy calculations. Maps corresponding to the residue pairwise interaction free energies decomposed into polar and nonpolar components between subunit 1: subunit 1 and subunit 2:subunit 2 are averaged and are presented in Fig. S3 (HI18:IAPP complex), with covalently bonded residues excluded from the calculations. Further analysis shows that intramolecular residue interactions within a subunit are nearly identical across all investigated complexes.

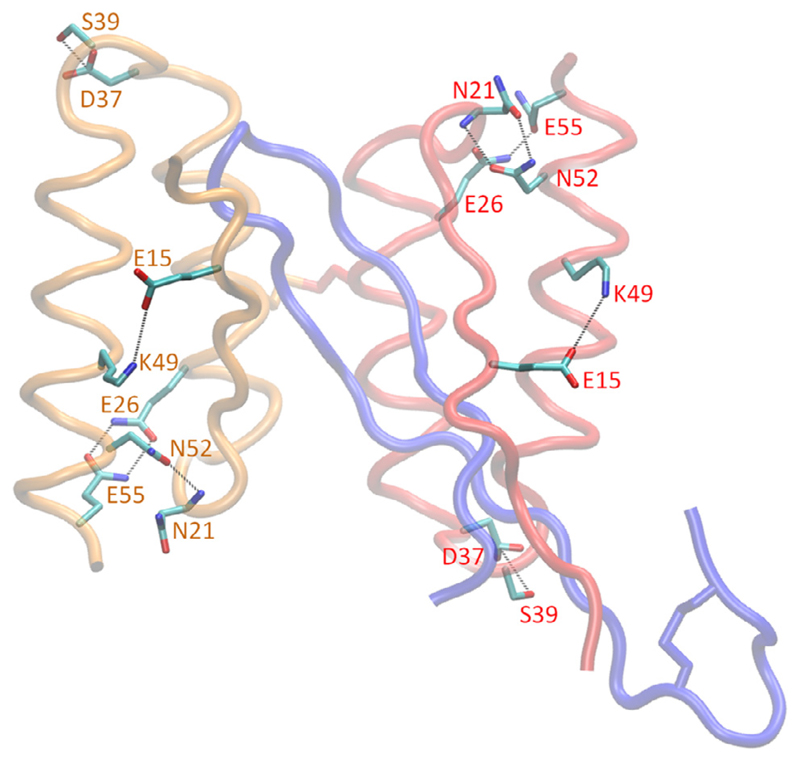

Aside from intra-helical interactions stabilizing the secondary structure of the residue motifs 24–37 and 41–56 of the β-wrapin subunits, the tertiary structure of both β-wrapin subunits are stabilized through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and salt-bridges. Between the two helices within each monomer subunit, a cluster of strong nonpolar interactions (Fig. S3) are formed between residues within the motif 44–56 and residues within the motif 17–34 of the opposite helix that lock the conformation of each β-wrapin monomer subunit. Additionally, within both subunits, Glu15 forms a salt-bridge with Lys49, the OD1 atom and backbone O of Asn21 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone N and ND2 atom of Asn52 respectively, the side chain polar groups of Gln26 and Gln55 form hydrogen bonds, and the side chain hydroxyl group of Ser39 forms a hydrogen bond with the negatively charged groups of Asp37. The hydrogen bond between Ser39 and Asp37 appears to be crucial to the stability of the loop connecting the two helices within the subunits. The key polar interactions within each subunit are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Molecular graphics images of the intra-subunit polar interactions within the monomer subunits of the HI18:IAPP complex. HI18 subunits 1 and 2 are shown in red and orange tube representation, respectively, and IAPP is shown in blue tube representation. The specified hydrogen bond and salt-bridge interactions are indicated with black dotted lines. These polar interactions are present for all β-wrapin:IAPP complexes investigated in this study, stabilizing the tertiary structure of the monomer subunits. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

According to previous studies, improved intramolecular interactions within β-wrapin monomer subunits can contribute to the enhanced binding of a β-wrapin (Orr et al., 2016; Lindberg et al., 2015). The introduction of mutations to a β-wrapin strengthening the key intramolecular interactions identified above may lead to β-wrapins with increased affinities for amyloidogenic proteins. Introduction of mutations at residue positions 17–34 and 44–56 could improve nonpolar interactions between helices within the monomer subunit, and potentially further enhance binding in future studies. Additionally, the results suggest that in the potential design of novel β-wrapins with higher affinities, care should be taken to avoid mutations disrupting the key identified nonpolar and polar interactions stabilizing the monomer β-wrapin subunits.

3.7. Absence of interactions acting as switches diminishing β-wrapin affinities for IAPP

To determine whether interactions that diminish β-wrapin affinity for amyloidogenic proteins are present within the β-wrapin:IAPP complexes, we calculated the average pairwise interaction free energies between β-wrapin subunit residues and IAPP as well as between β-wrapin residues of opposite subunits in all β-wrapin:IAPP complexes investigated. Using AS10 as a basis, we calculated the independent polar and nonpolar residue pairwise interaction free energy differences (ΔΔG) for all β-wrapin:IAPP complexes with respect to the AS10:IAPP complex. In our previous study, through an analogous comparative analysis using interaction free energy differences, we identified interactions acting as potential switches diminishing the affinity of β-wrapins ZAβ3 and AS69 for α-syn and Aβ, respectively (Orr et al., 2016). We projected these potential switches onto the residue pairwise interaction free energies of the AS69:IAPP and ZAβ3:IAPP complexes and verified that none of the interactions that diminish the affinity of ZAβ3 for α-syn or the affinity of AS69 for Aβ are expected to diminish the affinity of ZAβ3 or AS69 for IAPP.

Using the same criterion used in our previous study (Orr et al., 2016), we determined the residue pairs for which the average polar or non-polar ΔΔG interaction free energy value is less than −0.6 kcal/mol in at least one of the HI18:IAPP, AS69:IAPP, and ZAβ3:IAPP complexes, in comparison to the AS10:IAPP complex (see Eq. (3)). All three identified residue pair interactions (Supplementary Table S1) have a significantly large value of standard deviation, denoting that the presence of such unfavorable interactions is not reproducible across all multiple MD simulation runs, and thus, the specific interactions cannot be considered as interactions indicative of reduced affinity of a β-wrapin in complex with IAPP.

The absence of potential switches diminishing the affinity of AS10, AS69, and ZAβ3 to IAPP suggests that IAPP may be a more promiscuous β-wrapin target than Aβ and α-syn, which are analyzed in detail in Orr et al., 2016. This can be due to the lower number of charged residues located in the core of the β-wrapin complex in IAPP (one) compared to Aβ and α-syn (three and four, respectively). More specifically, the charged domains, Aβ-18VFFAED23 and α-syn-38LYVGSK43 are key domains determining binding specificity of a β-wrapin to the two amyloidogenic proteins (Orr et al., 2016). The corresponding domain in IAPP based on structural superposition of AS10:IAPP/Aβ/α-syn complexes, 14NFLVHS19, is neutral, assuming that histidine is deprotonated. The neutral charge of this segment might allow IAPP to be less selective than Aβ and α-syn.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we present the binding properties of β-wrapins to IAPP by combining computational and experimental methods. We uncovered that the Ala10Glu mutation in the flexible N-terminal domain of HI18 contributes significantly to HI18’s enhanced IAPP binding by establishing electrostatic interactions with Lys1 of IAPP. We show that β-wrapins ZAβ3 and AS69, which were engineered to bind to Aβ and α-syn, respectively, have similar affinities to IAPP as AS10; IAPP is less selective than Aβ and α-syn in binding to β-wrapins, potentially due to a lesser amount of charged residues sequestered in the core of the β-wrapin upon binding. In addition, we detected common non-polar and polar interactions between the β-wrapin residues and corresponding amyloidogenic protein (Aβ, α-syn, and IAPP) residues that can account for the multi-targeted binding of β-wrapins to amyloidogenic targets. Our study suggests that the design of high-affinity multi-targeted β-wrapins should (i) achieve optimization of interactions with corresponding target residues in the complex core that forms upon coupled folding-binding, and (ii) exploit dynamic interactions with peripheral segments of the amyloidogenic targets that remain structurally flexible in the bound state.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2018.02.013.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of Professor Christodoulos A. Floudas, a dearly valued member of the computational chemical engineering, optimization, and the biophysical chemistry community. This research is supported by the National Institute on Aging, NIH, R03AG058100 (PT), by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, grant agreement No 726368 (WH), and by the Texas A&M University Graduate Diversity Fellowship from the TAMU Office of Graduate and Professional Studies (AAO). All MD simulations and free energy calculations were performed on the Ada supercomputing cluster at the Texas A&M High Performance Research Computing Facility.

References

- Akter K, Lanza EA, Martin SA, Myronyuk N, Rua M, Raffa RB. Diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease: shared pathology and treatment? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71(3):365–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(3):332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadei A, Linssen AB, Berendsen HJ. Essential dynamics of proteins. Proteins. 1993;17(4):412–425. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbagallo M, Dominguez LJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. World J Diabetes. 2014;5(6):889–893. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i6.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best RB, Zhu X, Shim J, Lopes PE, Mittal J, Feig M, Mackerell AD., Jr Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(9):3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Brooks CL, 3rd, Mackerell AD, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, et al. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(10):1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng PN, Liu C, Zhao M, Eisenberg D, Nowick JS. Amyloid β-sheet mimics that antagonize amyloid aggregation and reduce amyloid toxicity. Nat Chem. 2012;4(11):927–933. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Jin UH, Davidson LA, Chapkin RS, Jayaraman A, Tamamis P, Orr A, Allred C, Denison MS, Soshilov A, Weaver E, et al. Editor’s highlight: microbial-derived 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid and related compounds as aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists/antagonists: structure-activity relationships and receptor modeling. Toxicol Sci. 2017;155(2):458–473. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, Walker R, Hubbard RA, Li G, Nathan DM, Zheng H, Haneuse S, Craft S, Montine TJ, Kahn SE, McCormick W, et al. Glucose levels and risk of dementia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):540–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215740. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deidda G, Jonnalagadda SVR, Spies JW, Ranella A, Mossou E, Forsyth VT, Mitchell EP, Mitraki A, Tamamis P. Self-assembled amyloid peptides with Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motifs as scaffolds for tissue engineering. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2017;3(7):1404–1416. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eargle J, Wright D, Luthey-Schulten Z. Multiple Alignment of protein structures and sequences for VMD. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:504–506. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S, Ryde U. How to obtain statistically converged MM/GBSA results. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(4):837–846. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilead S, Gazit E. The role of the 14-20 domain of the islet amyloid polypeptide in amyloid formation. Exp Diabetes Res. 2008;2008 doi: 10.1155/2008/256954. 256954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke H, Case DA. Converging free energy estimates: MM-PB(GB)SA studies on the protein-protein complex Ras-Raf. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:238–250. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönwall C, Jonsson A, Lindström S, Gunneriusson E, Ståhl S, Herne N. Selection and characterization of Affibody ligands binding to Alzheimer amyloid beta peptides. J Biotechnol. 2007;128(1):162–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberthür U, Caflisch A. FACTS: fast analytical continuum treatment of solvation. J Comput Chem. 2008;29(5):701–715. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann U. Parallel tempering algorithm for conformational studies of biological molecules. Chem Phys Lett. 1997;281:140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Härd T, Lendel C. Inhibition of amyloid formation. J Mol Biol. 2012;421(4–5):441–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath I, Wittung-Stafshede P. Cross-talk between amyloidogenic proteins in type-2 diabetes and Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;13(44):12473–12477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610371113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer W, Grönwall C, Jonsson A, Ståhl S, Härd T. Stabilization of a β-hairpin in monomeric Alzheimer’s amyloid-β peptide inhibits amyloid formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(13):5099–5104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711731105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Jousilahti P, Bidel S, Antikainen R, Tuomilehto J. Type 2 diabetes and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):842–847. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Mucke L. Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell. 2012;148(6):1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukushima K, Nemoto K. Exchange Monte Carlo method and application to spin glass simulations. J Phys Soc Jpn. 1996;65:1604–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Molec Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K, Barisone GA, Diaz E, Jin LW, DeCarli C, Despa F. Amylin deposition in the brain: a second amyloid in Alzheimer disease? Ann Neurol. 2013;74(4):517–526. doi: 10.1002/ana.23956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2004;53(2):474–481. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonnalagadda SVR, Ornithopoulou E, Orr AA, Mossou E, Forsyth VT, Mitchell EP, Bowler MW, Mitraki A, Tamamis P. Computational design of amyloid self-assembling peptides bearing aromatic residues and the cell adhesive motif Arg-Gly-Asp. Mol Syst Des Eng. 2017;2:321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury GA, Smadbeck J, Tamamis P, Vandris AC, Kieslich CA, Floudas CA. Forcefield_NCAA: ab initio charge parameters to aid in the discovery and design of therapeutic proteins and peptides with unnatural amino acids and their application to complement inhibitors of the compstatin family. ACS Synth Biol. 2014;3(12):855–869. doi: 10.1021/sb400168u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieslich CA, Tamamis P, Gorham RD, Jr, Lopez de Victoria A, Sausman UN, Archontis G, Morikis D. Exploring protein-protein and protein-ligand interactions in the immune system using molecular dynamics and continuum electrostatics. Curr Phys Chem. 2012;2(4):324–343. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles TP, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM. The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(6):384–396. doi: 10.1038/nrm3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongsted J, Söderhjelm P, Ryde U. How accurate are continuum solvation models for drug-like molecules? J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2009;23(7):395–409. doi: 10.1007/s10822-009-9271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroner Z. The relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes: type 3 diabetes? Altern Med Rev. 2009;14(4):373–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel HA, Overk CR, Oueslati A, Masliah E. The many faces of α-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis T, Versace R. The treatment of solvent in multiscale biophysical modeling. Isr J Chem. 2014;54:1074–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg H, Härd T, Löfblom J, Ståhl S. A truncated and dimeric format of an Affibody library on bacteria enables FACS-mediated isolation of amyloid–beta aggregation inhibitors with subnanomolar affinity. Biotechnol J. 2015;10(11):1707–1718. doi: 10.1002/biot.201500131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López de Victoria A, Tamamis P, Kieslich CA, Morikis D. Insights into the structure, correlated motions, and electrostatic properties of two HIV-1 gp120 V3 loops. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luheshi LM, Hoyer W, de Barros TP, van Dijk Härd I, Brorsson A, Macao B, Persson C, Crowther CC, Lomas DA, Ståhl S, Dobson CM, et al. Sequestration of the Abeta peptide prevents toxicity and promotes degradation in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(3):e1000334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirecka EA, Feuerstein S, Gremer L, Schröder GF, Stoldt M, Willbold D, Hoyer W. β-Hairpin of islet amyloid polypeptide bound to an aggregation inhibitor. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33474. doi: 10.1038/srep33474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirecka EA, Gremer L, Schiefer S, Oesterhelt F, Stoldt M, Willbold D, Hoyer W. Engineered aggregation inhibitor fusion for production of highly amyloidogenic human islet amyloid polypeptide. J Biotechnol. 2014b;191:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirecka EA, Shaykhalishahi H, Gauhar A, Akgül Ş, Lecher J, Willbold D, Stoldt M, Hoyer W. Sequestration of a β-hairpin for control of α-synuclein aggregation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014a;53(16):4227–4230. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal K, Mani RJ, Katare DP. Type 3 diabetes: cross talk between differentially regulated proteins of type 2 diabetes mellitus and alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25589. doi: 10.1038/srep25589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira PI. High-sugar diets, type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(4):440–445. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328361c7d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nymeyer H, Gnanakaran S, Garcia A. Atomic simulations of protein folding, using the replica exchange algorithm. Methods Enzymol. 2004;30:119–149. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr AA, Wördehoff MM, Hoyer W, Tamamis P. Uncovering the binding and specificity of β-wrapins for amyloid-β and α-synuclein. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120(50):12781–12794. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b08485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskarsson ME, Paulsson JF, Schultz SW, Ingelsson M, Westermark P, Westermark GT. In vivo seeding and cross-seeding of localized amyloidosis: a molecular link between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(3):834–846. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaleo E, Mereghetti P, Fantucci P, Grandori R, De Gioia L. Free-energy landscape, principal component analysis, and structural clustering to identify representative conformations from molecular dynamics simulations: the myoglobin case. J Mol Graph Model. 2009;27(8):889–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsson JF, Ludvigsson J, Carlsson A, Casas R, Forsander G, Ivarsson SA, Kockum I, Lernmark Å, Marcus C, Lindblad B, Westermark GT. High plasma levels of islet amyloid polypeptide in young with new-onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts HL, Schneider BL, Brown DR. α-Synuclein increases β-amyloid secretion by promoting β-/γ-secretase processing of APP. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanbonmatsu KY, Garcia AE. Structure of Met-enkephalin in explicit aqueous solution using replica exchange molecular dynamics. Proteins. 2002;46:225–234. doi: 10.1002/prot.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandyk R. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Neurosci. 1993;69(1–4):125–130. doi: 10.3109/00207459309003322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schernhammer E, Hansen J, Rugbjerg K, Wermuth L, Ritz B. Diabetes and the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in Denmark. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(5):1102–1108. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeber M, Cecchini M, Rao F, Settanni G, Caflisch A. Wordom: a program for efficient analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2625–2627. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeber M, Felline A, Raimondi F, Muff S, Friedman R, Rao F, Caflisch A, Fanelli F. Wordom: a user-friendly program for the analysis of molecular structures, trajectories, and free energy surfaces. J Comput Chem. 2011;32(6):1183–1194. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaykhalishahi H, Mirecka EA, Gauhar A, Grüning CS, Willbold D, Härd T, Stoldt M, Hoyer W. A β-hairpin-binding protein for three different disease-related amyloidogenic proteins. ChemBioChem. 2015;16:411–414. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar GR, Lakshmi G, Nagamani G. Emerging links between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(5):744–751. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i5.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Still WC, Tempczyk A, Hawley RC, Hendrickson T. Semianalytical treatment of solvation for molecular mechanics and dynamics. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112(16):6127–6129. [Google Scholar]

- Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen R, Wang J. Replica Monte Carlo simulation of spin-glasses. Phys Rev Lett. 1986;57:2607–2609. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.57.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Kasotakis E, Mitraki A, Archontis G. Amyloid-like self-assembly of peptide sequences from the adenovirus fiber shaft: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:15639–15647. doi: 10.1021/jp9066718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Archontis G. Amyloid-like self-assembly of a dodecapeptide sequence from the adenovirus fiber shaft: perspectives from molecular dynamics simulations. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2010;357:717–722. [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Morikis D, Floudas CA, Archontis G. Species specificity of the complement inhibitor compstatin investigated by all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Proteins. 2010;78(12):2655–2667. doi: 10.1002/prot.22780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, López de Victoria A, Gorham RD, Jr, Bellows-Peterson ML, Pierou P, Floudas CA, Morikis D, Archontis G. Molecular dynamics in drug design: new generations of compstatin analogs. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2012;79(5):703–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Pierou P, Mytidou C, Floudas CA, Morikis D, Archontis G. Design of a modified mouse protein with ligand binding properties of its human analog by molecular dynamics simulations: the case of C3 inhibition by compstatin. Proteins. 2011;79(11):3166–3179. doi: 10.1002/prot.23149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Floudas CA. Molecular recognition of CXCR4 by a Dual Tropic HIV-1 gp120 V3 Loop. BioPhys J. 2013;105(6):1502–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Floudas CA. Molecular Recognition of CCR5 by an HIV-1 gp120 V3 Loop. PLoS One. 2014a;9(4):e95767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Floudas CA. Elucidating a key anti-HIV-1 and cancer-associated axis: the structure of CCL5 (Rantes) in complex with CCR5. Sci Rep. 2014b;4:5447. doi: 10.1038/srep05447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Terzaki K, Kassinopoulos M, Mastrogiannis L, Mossou E, Forsyth VT, Mitchell EP, Mitraki A, Archontis G. Self-assembly of an aspartate-rich sequence from the adenovirus fiber shaft: insights from molecular dynamics simulations and experiments. J Phys Chem B. 2014a;118(7):1765–1774. doi: 10.1021/jp409988n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Kasotakis E, Archontis G, Mitraki A. Combination of theoretical and experimental approaches for the design and study of fibril-forming peptides. Methods Mol Biol. 2014b;1216:53–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1486-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamis P, Kieslich CA, Nikiforovich GV, Woodruff TM, Morikis D, Archontis G. Insights into the mechanism of C5aR inhibition by PMX53 via implicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations and docking. BMC BioPhys. 2014c;7:5. doi: 10.1186/2046-1682-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao K, Wang J, Zhou P, Wang PC, Xu H, Zhao X, Lu JR. Self-assembly of short aβ(16-22) peptides: effect of terminal capping and the role of electrostatic interaction. Langmuir. 2011;27(6):2723–2730. doi: 10.1021/la1034273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng PK, Eisenberg D. Short protein segments can drive a non-fibrillizing protein into the amyloid state. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2009;22(8):531–536. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenidis K, Waldner M, Bernhagen J, Fischle W, Bergmann M, Weber M, Merkle ML, Voelter W, Brunner H, Kapurniotu A. Identification of a penta- and hexapeptide of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) with amyloidogenic and cytotoxic properties. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:1055–1071. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita T. Islet amyloid polypeptide in pancreatic islets from type 1 diabetic subjects. Islets. 2011;3(4):166–174. doi: 10.4161/isl.3.4.15875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdile G, Fuller SJ, Martins RN. The role of type 2 diabetes in neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;84:22–38. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlberg E, Rahman MM, Lindberg H, Gunneriusson E, Schmuck B, Lendel C, Sandgren M, Löfblom J, Ståhl S, Härd T. Identification of proteins that specifically recognize and bind protofibrillar aggregates of amyloid-β. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5949. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P, Andersson A, Westermark GT. Islet amyloid polypeptide, islet amyloid, and diabetes mellitus. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(3):795–826. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Yan R, Roy A, Xu D, Poisson J, Zhang Y. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WQ, Townsend M. Insulin resistance and amyloidogenesis as common molecular foundation for type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim BioPhys Acta. 2009;1792(5):482–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.