Abstract

Importance

Retention in addiction treatment is associated with reduced mortality for individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD). Although clinical trials support use of OUD medications among youths (adolescents and young adults), data on timely receipt of buprenorphine hydrochloride, naltrexone hydrochloride, and methadone hydrochloride and its association with retention in care in real-world treatment settings are lacking.

Objectives

To identify the proportion of youths who received treatment for addiction after diagnosis and to determine whether timely receipt of OUD medications is associated with retention in care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used enrollment data and complete health insurance claims of 2.4 million youths aged 13 to 22 years from 11 states enrolled in Medicaid from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2015. Data analysis was performed from August 1, 2017, to March 15, 2018.

Exposures

Receipt of OUD medication (buprenorphine, naltrexone, or methadone) within 3 months of diagnosis of OUD compared with receipt of behavioral health services alone.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Retention in care, with attrition defined as 60 days or more without any treatment-related claims.

Results

Among 4837 youths diagnosed with OUD, 2752 (56.9%) were female and 3677 (76.0%) were non-Hispanic white. Median age was 20 years (interquartile range [IQR], 19-21 years). Overall, 3654 youths (75.5%) received any treatment within 3 months of diagnosis of OUD. Most youths received only behavioral health services (2515 [52.0%]), with fewer receiving OUD medications (1139 [23.5%]). Only 34 of 728 adolescents younger than 18 years (4.7%; 95% CI, 3.1%-6.2%) and 1105 of 4109 young adults age 18 years or older (26.9%; 95% CI, 25.5%-28.2%) received timely OUD medications. Median retention in care among youths who received timely buprenorphine was 123 days (IQR, 33-434 days); naltrexone, 150 days (IQR, 50-670 days); and methadone, 324 days (IQR, 115-670 days) compared with 67 days (IQR, 14-206 days) among youths who received only behavioral health services. Timely receipt of buprenorphine (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.52-0.64), naltrexone (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.43-0.69), and methadone (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.47) were each independently associated with lower attrition from treatment compared with receipt of behavioral health services alone.

Conclusions and Relevance

Timely receipt of buprenorphine, naltrexone, or methadone was associated with greater retention in care among youths with OUD compared with behavioral treatment only. Strategies to address the underuse of evidence-based medications for youths with OUD are urgently needed.

This cohort study uses Medicaid claims data to identify the proportion of youths who receive treatment for addiction shortly after diagnosis and to determine whether timely receipt of medications for opioid use disorder is associated with longer retention in care compared with behavioral treatment only.

Key Points

Question

What percentage of youths receive medications for opioid use disorder shortly after diagnosis, and are those who receive medications early after diagnosis more likely to remain in care compared with those who receive behavioral treatment only?

Findings

In this multistate cohort of 4837 youths with opioid use disorder, 1 of 21 adolescents younger than 18 years and 1 of 4 young adults aged 18 to 22 years received medication for opioid use disorder within 3 months of diagnosis. Youths who received buprenorphine were 42% less likely to discontinue treatment, those who received naltrexone were 46% less likely to discontinue treatment, and those who received methadone were 68% less likely to discontinue treatment compared with youths who received behavioral treatment only.

Meaning

Pharmacotherapy, a critical evidence-based intervention to address opioid use disorder, may be underused in youths with this disorder; those who receive medications shortly after diagnosis may be more likely to remain in care than youths who receive behavioral health services only.

Introduction

As the United States confronts the opioid crisis, morbidity and mortality from opioids continue to increase among youths (adolescents and young adults). Deaths from overdose, hospitalizations for nonfatal overdose, and diagnoses of opioid use disorder (OUD) among youths have increased since the early 2000s.1,2,3,4 Multiple major professional organizations and government bodies recommend providing youths of any age with effective treatment as early as possible, including use of OUD medications buprenorphine hydrochloride, naltrexone hydrochloride, or methadone hydrochloride.5,6,7,8 Despite these evidence-based recommendations, youths are only one-tenth as likely as adults to receive medication for OUD,1,9 likely owing to poor availability of pediatric prescribers, clinician discomfort with medications, and stigma surrounding medication treatment.10,11 Even when youths receive medications for OUD, it is often only after clinicians have exhausted other nonpharmacologic treatment options, such as behavioral health services.1,9,11

Ensuring timely treatment with OUD medications may be especially important in light of data showing that adults who receive medications are more likely to be retained in addiction treatment.12,13,14 Because living with addiction can be a lifelong process that involves cycles of relapse and recovery, maximizing retention in care is a central strategy in the pursuit of decreased mortality among individuals with OUD.15,16 In longitudinal cohort studies of adults who have initiated OUD treatment, all-cause mortality when an individual is receiving treatment is less than half that observed after discontinuing treatment.15 Because attrition from OUD treatment is greater for youths than it is for adults, strategies to prevent youths from leaving care are urgently needed.17,18,19,20 Small randomized clinical trials have shown that, under experimental conditions, youths who receive medication treatment for OUD are more likely to be retained in treatment up to 12 weeks.20,21,22 However, we know of no large studies with follow-up beyond this time frame or studies that have used data from real-world treatment settings.

Using an 11-state sample of youths with OUD enrolled in Medicaid, we sought to identify the frequency with which youths who presented to care for OUD received timely addiction treatment, including behavioral health services and/or OUD medications, and the association between timely receipt of OUD medications and subsequent retention in care. We hypothesized that timely receipt of buprenorphine, naltrexone, or methadone would be associated with longer retention in addiction treatment compared with behavioral treatment only.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

This retrospective cohort study was conducted using the 2014-2015 Truven-IBM Watson Health MarketScan Medicaid Database, which included data for 2 490 114 youths aged 13 to 22 years with at least 6 months of continuous enrollment and all associated inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, behavioral health, and retail prescription drug claims between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2015. Data were collected from 11 deidentified states representing all census regions of the United States. As all data were deidentified and the study was not considered to be human participants research by the Boston University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, approval and patient consent were waived.

To generate the study sample, the following eligibility criteria were applied to identify all youths initiating a new episode of care for OUD: (1) primary or secondary diagnosis of OUD using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes 304.0x (opioid-type dependence) and 304.7x (combinations of opioid-type drug with any other drug dependence) in at least 1 inpatient or emergency department claim or 2 outpatient claims1,23; (2) before diagnosis, a 60-day period without another OUD diagnosis or receipt of buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone1,23,24; and (3) at least 3 months of enrollment data after diagnosis (eFigure in the Supplement).1,23 We defined the date of the first observed OUD diagnosis as the start of the episode of care. Data from the first observed episode of care for OUD were included in analyses; any subsequent episodes of care were excluded.

Variables

Timely addiction treatment was defined as receipt of behavioral health services and/or OUD medication (buprenorphine, naltrexone, or methadone) within 3 months of diagnosis of OUD. The 3-month window was selected based on prior research1,23; sensitivity analyses also examined receipt of addiction treatment within 1, 2, 6, 9, and 12 months of diagnosis. Behavioral health services were identified using claims for individual outpatient, group outpatient, intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, residential, and inpatient treatment based on Current Procedural Terminology and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes (eTable 1 in the Supplement).25,26 Receipt of each of the 3 OUD medications was identified as follows: buprenorphine, using pharmacy claims that included a National Drug Code for sublingual buprenorphine or buprenorphine-naloxone1,23; naltrexone, using pharmacy claims that included a National Drug Code for oral or long-acting injectable naltrexone and using HCPCS code J2315 (naltrexone, depot form); and methadone, using HCPCS code H0020 (methadone administration and/or service)27,28 (eTable 2 in the Supplement).1

Retention in care was defined as time from receipt of first addiction treatment (either behavioral health services or OUD medication) to time of treatment discontinuation. An individual was considered to have discontinued treatment if at least 60 days passed without a claim for behavioral health services or OUD medication. The date of treatment discontinuation was defined as the last date of any qualifying claim. Youths were censored if they disenrolled from their insurance plan.

Sociodemographic covariates included age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, and Medicaid eligibility (disability or income). Clinical covariates included (at the time of diagnosis or during the preceding 3 months) pregnancy, depression, anxiety disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, alcohol use disorder, other substance use disorder, acute pain condition, or chronic pain condition based on ICD-9 diagnosis codes (eTable 3 in the Supplement).29,30,31,32 Covariates were selected based on their established association with OUD and potential influences on treatment and retention in care.1,5,6,9,33

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with receipt of any timely addiction treatment were identified using multivariable logistic regression. Among youths who received timely addiction treatment, a subsequent model examined characteristics associated with receipt of OUD medication (with or without behavioral health services) compared with receipt of behavioral health services alone. Multivariable models included all sociodemographic and clinical covariates. Characteristics of youths receiving each of the 3 OUD medications were compared using χ2 tests or Fisher exact test.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to measure retention in care among youths who received timely OUD medications compared with those who received only behavioral health services. Because the exposure of interest (timely receipt of OUD medication) was a subset of the outcome (ongoing receipt of behavioral health services and/or OUD medication), a separate Kaplan-Meier curve examined the outcome of retention in behavioral health services alone. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was then used to identify the association of receiving timely OUD medications with retention in care. Some youths had an initial claim for addiction treatment but did not receive any subsequent services, which resulted in violation of the proportional hazards assumption of Cox regression.34 The analysis was therefore limited to youths who had at least 1 subsequent claim after their initial claim; potential differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between youths with and without subsequent claims were identified using multivariable logistic regression. Models examined retention in care in association with the initial OUD medication used (buprenorphine, naltrexone, methadone, or none) and were adjusted for receipt of higher levels of behavioral health care (intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization, residential care, or inpatient care)25 as well as all sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All statistical tests were 2-sided and considered to be significant at P < .05.

Results

Sample

The study included data for 2 483 250 youths aged 13 to 22 years who were enrolled in Medicaid, among whom 4837 (0.2%) initiated a new episode of care for OUD and thus met criteria for inclusion in the sample. The median age at diagnosis was 20 years (interquartile range [IQR], 19-21 years), and the sample included 2752 females, 2085 males, and 3677 non-Hispanic white patients. Females comprised 67 of 165 youths aged 13 to 15 years (40.6%), 233 of 563 aged 16 and 17 years (41.4%), 1030 of 1846 aged 18 to 20 years (55.8%), and 1422 of 2263 aged 21 and 22 years (62.8%). Overall, 773 females (28.1%) were pregnant at the time of OUD diagnosis or in the preceding 3 months.

Timely Addiction Treatment

Overall, 3654 youths (75.5%) received any timely addiction treatment (Table 1). The percentage of youths receiving any treatment did not differ significantly between adolescents younger than 18 years (554 of 728 [76.1%]; 95% CI, 73.0%-79.2%) and young adults aged 18 years or older (3029 of 4109 [73.7%]; 95% CI, 72.4%-75.1%). Most of the 3654 youths receiving timely addiction treatment received behavioral health services (3238 [88.6%]) either alone or in combination with OUD medications. Of youths receiving any behavioral health services, 872 (26.9%) received intensive outpatient treatment or partial hospitalization and 1664 (51.4%) received residential or inpatient care. The remaining 702 (21.7%) received outpatient care only.

Table 1. Receipt of Addiction Treatment Within 3 Months of Diagnosis Among 4837 Medicaid-Enrolled Youths With Opioid Use Disorder.

| Characteristic | Total, No. | Received Any Timely Treatment (n = 3654)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | ||

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| 21-22 | 2263 | 1550 (68.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| 18-20 | 1846 | 1479 (80.1) | 1.09 (0.94-1.26) |

| 16-17 | 563 | 432 (76.7) | 1.24 (0.97-1.58) |

| 13-15 | 165 | 122 (73.9) | 0.68 (0.47-0.98) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2085 | 1590 (76.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 2752 | 2064 (75.0) | 1.02 (0.87-1.18) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White non-Hispanic | 3677 | 2876 (78.2) | 1 [Reference] |

| Black non-Hispanic | 388 | 242 (62.4) | 0.51 (0.41-0.65) |

| Hispanic | 55 | 41 (74.5) | 0.83 (0.44-1.54) |

| Other | 717 | 495 (69.0) | 0.64 (0.54-0.77) |

| Eligible for Medicaid owing to disability | |||

| No | 4571 | 3510 (76.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 266 | 144 (54.1) | 0.41 (0.32-0.54) |

| Pregnancyc | |||

| No | 4064 | 3109 (76.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 773 | 545 (70.5) | 0.73 (0.60-0.88) |

| Depressionc | |||

| No | 3227 | 2415 (74.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1610 | 1239 (77.0) | 1.28 (1.08-1.51) |

| Anxiety disorderc | |||

| No | 3439 | 2616 (76.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1398 | 1038 (74.2) | 0.84 (0.71-1.00) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderc | |||

| No | 4244 | 3191 (75.2) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 593 | 463 (78.1) | 1.21 (0.97-1.53) |

| Alcohol use disorderc | |||

| No | 4138 | 3082 (74.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 699 | 572 (81.8) | 1.43 (1.15-1.78) |

| Other substance use disorderc | |||

| No | 2307 | 1740 (75.4) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 2530 | 1914 (75.7) | 0.94 (0.82-1.08) |

| Acute pain conditionc | |||

| No | 3282 | 2505 (76.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1555 | 1149 (73.9) | 1.16 (0.98-1.38) |

| Chronic pain conditionc | |||

| No | 3253 | 2555 (78.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1584 | 1099 (69.4) | 0.59 (0.50-0.69) |

Had a claim for either behavioral health services or medication for opioid use disorder within 3 months of diagnosis.

Adjusted for all other covariates listed in the table.

At or during the 3 months before receiving a diagnosis of opioid use disorder.

Only a minority of youths received timely buprenorphine, naltrexone, or methadone (1139 [23.5%]) (Table 2). Overall, 34 of 728 adolescents (4.7%; 95% CI, 3.1%-6.2%) received OUD medications compared with 1105 of 4109 young adults (26.9%; 95% CI, 25.5%-28.2%). Most of the 1139 youths who received medication also received concurrent behavioral health services (723 [63.5%]). Most youths who received an OUD medication received it within 1 month of diagnosis (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Type of Addiction Care Received Within 3 Months of Diagnosis Among 3654 Medicaid-Enrolled Youths Who Received Any Treatment for OUD.

| Characteristic | No./Total No. (%) | Receipt of OUD Medication, Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Health Services Only (n = 2515) | OUD Medication (n = 1139)a | ||

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| 21-22 | 889/1550 (57.4) | 661/1550 (42.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| 18-20 | 1035/1479 (70.0) | 444/1479 (30.0) | 0.78 (0.67-0.91) |

| 16-17 | 402/432 (93.1) | 30/432 (6.9) | 0.16 (0.11-0.24) |

| 13-15 | 118/122 (96.7) | 4/122 (3.3) | 0.08 (0.03-0.23) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1175/1590 (73.9) | 415/1590 (26.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 1340/2064 (64.9) | 724/2064 (35.1) | 1.06 (0.90-1.26) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White non-Hispanic | 1948/2876 (67.7) | 928/2876 (32.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Black non-Hispanic | 206/242 (85.1) | 36/242 (14.9) | 0.48 (0.33-0.70) |

| Hispanic | 31/41 (75.6) | 10/41 (24.4) | 0.68 (0.32-1.45) |

| Other | 330/495 (66.7) | 165/495 (33.3) | 1.01 (0.82-1.26) |

| Eligible for Medicaid owing to disability | |||

| No | 2391/3510 (68.1) | 1119/3510 (31.9) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 124/144 (86.1) | 20/144 (13.9) | 0.47 (0.28-0.77) |

| Pregnancyc | |||

| No | 2219/3109 (71.4) | 890/3109 (28.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 296/545 (54.3) | 249/545 (45.7) | 1.62 (1.31-2.00) |

| Depressionc | |||

| No | 1562/2415 (64.7) | 853/2415 (35.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 953/1239 (76.9) | 286/1239 (23.1) | 0.81 (0.67-0.98) |

| Anxiety disorderc | |||

| No | 1733/2616 (66.2) | 883/2616 (33.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 782/1038 (75.3) | 256/1038 (24.7) | 0.89 (0.72-1.09) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderc | |||

| No | 2135/3191 (66.9) | 1056/3191 (33.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 380/463 (82.1) | 83/463 (17.9) | 0.91 (0.69-1.21) |

| Alcohol use disorderc | |||

| No | 2020/3082 (65.5) | 1062/3082 (34.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 495/572 (86.5) | 77/572 (13.5) | 0.43 (0.33-0.56) |

| Other substance use disorderc | |||

| No | 1045/1740 (60.1) | 695/1740 (39.9) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1470/1914 (76.8) | 444/1914 (23.2) | 0.60 (0.52-0.70) |

| Acute pain conditionc | |||

| No | 1685/2505 (67.3) | 820/2505 (32.7) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 830/1149 (72.2) | 319/1149 (27.8) | 0.91 (0.74-1.10) |

| Chronic pain conditionc | |||

| No | 1755/2555 (68.7) | 800/2555 (31.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 760/1099 (69.2) | 339/1099 (30.8) | 1.30 (1.07-1.59) |

Abbreviation: OUD, opioid use disorder.

Includes youths who did and did not receive concurrent behavioral health services.

Adjusted for all other covariates listed in the table.

At or during the 3 months before receiving a diagnosis of opioid use disorder.

Of the 1139 youths who received timely OUD medications, 936 (82.2%) received buprenorphine, 135 (11.9%) received naltrexone, and 68 (6.0%) received methadone (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Adolescents were more likely to receive naltrexone than were young adults (12 of 34 [35.3%] vs 123 of 1105 [11.1%]; P < .001 for group difference). No adolescents received methadone.

Retention in Care

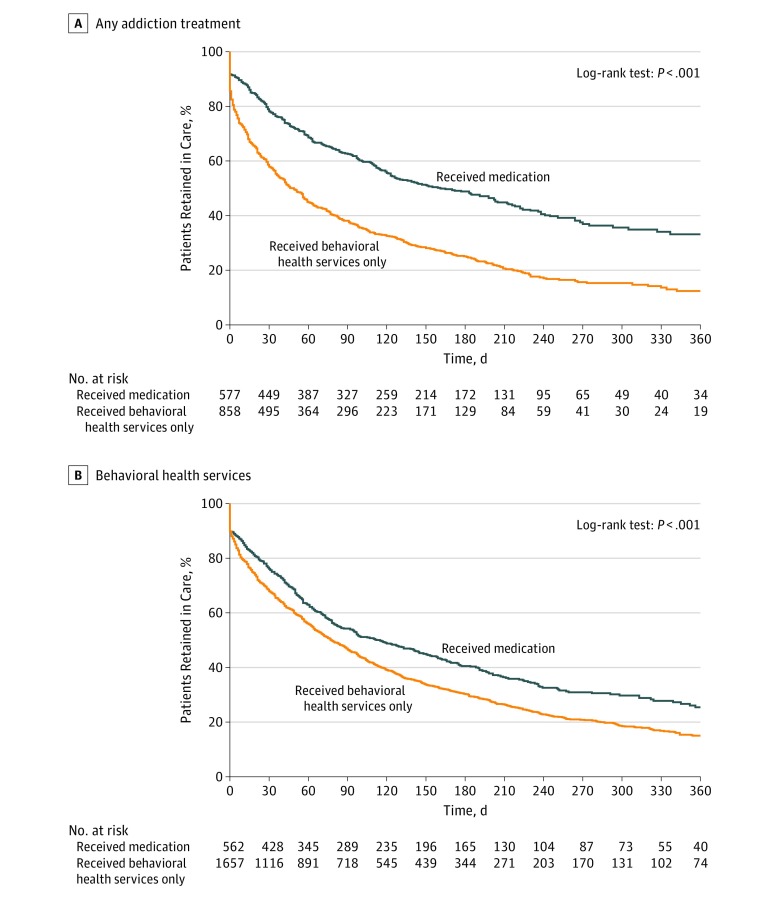

The 3654 youths who received any treatment contributed 13 185 person-months of follow-up. Overall, 2575 youths (70.5%) discontinued treatment (crude incidence density, 19.5 discontinuing events per 100 person-months). Youths who received timely OUD medications were more likely to be retained in any addiction treatment and more likely to be retained in behavioral health services (Figure).

Figure. Retention in Care According to Timely Receipt of Opioid Use Disorder Medication Within 3 Months of Diagnosis Among Youths.

Medications included buprenorphine hydrochloride, naltrexone hydrochloride, or methadone hydrochloride.

Median retention in care among youths who received only behavioral health services was shorter (67 days; IQR, 14-206 days) than that among those who received timely buprenorphine (123 days; IQR, 33-434 days), naltrexone (150 days; IQR, 50-670 days), or methadone (324 days; IQR, 115-670 days). Similarly, median duration of behavioral health services among youths who did not receive timely OUD medications was shorter (65 days; IQR, 13-204 days) than among those who received timely buprenorphine (108 days; IQR, 34-290 days), naltrexone (152 days; IQR, 55-670 days), or methadone (217 days; IQR, 41-354 days).

Of the 3654 youths who received any timely addiction treatment, 3247 (88.9%) met the criteria for inclusion in the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of retention in care (ie, had at least 1 subsequent claim for behavioral health services or an OUD medication); the remaining 407 youths (11.1%) were excluded to satisfy the proportional hazards assumption of Cox proportional hazards regression. Included youths were more likely than excluded youths to be pregnant (adjusted odds ratio, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.10-2.18); have received intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization, residential, or inpatient behavioral health services (adjusted odds ratio, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.86-3.08); have received buprenorphine (adjusted odds ratio, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.04-1.74); or have received methadone (adjusted odds ratio, 5.22; 95% CI, 1.26-21.53). Of included youths, 97 (3.0%) had claims for detoxification services. Of the 3238 youths who had an initial behavioral health claim, 2885 (89.1%) had a subsequent claim.

Compared with youths who received only behavioral health services, those who received timely buprenorphine were 42% (95% CI, 36%-48%) less likely to discontinue addiction treatment, those who received timely naltrexone were 46% (95% CI, 31%-57%) less likely to discontinue addiction treatment, and those who received timely methadone were 68% (95% CI, 53%-78%) less likely to discontinue addiction treatment (Table 3). Compared with youths who received only behavioral health services, those who received timely buprenorphine were 27% (95% CI, 18%-36%) less likely to discontinue behavioral health services, those who received timely naltrexone were 43% (95% CI, 27%-56%) less likely to discontinue behavioral health services, and those who received timely methadone were 53% (95% CI, 32%-67%) less likely to discontinue behavioral health services (Table 3).

Table 3. Retention in Care Among Youths With at Least 2 Claims for Addiction Treatment.

| Characteristic | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Attrition From Any Addiction Treatment (n = 3247)b,c | Attrition From Behavioral Health Services (n = 2885)b | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Age ≥21 y | 1.63 (1.45-1.83) | 1.59 (1.41-1.80) |

| Male | 1.13 (1.03-1.24) | 1.13 (1.02-1.24) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.03 (0.93-1.14) | 1.05 (0.94-1.18) |

| Eligible for Medicaid owing to disability | 0.63 (0.49-0.80) | 0.60 (0.46-0.78) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Pregnancyd | 0.87 (0.75-0.99) | 0.90 (0.77-1.04) |

| Comorbid behavioral health diagnosisd,e | 1.04 (0.95-1.14) | 1.01 (0.92-1.11) |

| Comorbid alcohol or other substance use disorderd | 1.02 (0.93-1.12) | 1.00 (0.91-1.10) |

| Acute or chronic pain conditiond | 0.92 (0.84-1.01) | 0.92 (0.83-1.01) |

| Treatment received | ||

| Higher level of behavioral health services within 3 mo of initiating episode of caref | 0.94 (0.85-1.02) | 0.92 (0.83-1.01) |

| Timely opioid use disorder medication within 3 mo of diagnosis | ||

| No medication | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Buprenorphine | 0.58 (0.52-0.64) | 0.73 (0.64-0.82) |

| Naltrexone | 0.54 (0.43-0.69) | 0.57 (0.44-0.73) |

| Methadone | 0.32 (0.22-0.47) | 0.47 (0.33-0.68) |

Multivariable models included all covariates listed in the table.

Attrition defined as at least 60 days without any claims for services.

Includes receipt of any behavioral health services or opioid use disorder medications.

At or during the 3 months before receiving a diagnosis of opioid use disorder.

Depression, anxiety, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Includes intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization, residential care, or inpatient care.

Discussion

In this multistate study of addiction treatment and retention in care, we found that three-quarters of youths diagnosed with OUD received treatment within 3 months. However, most treatment included behavioral health services only, and fewer than 1 of 4 youths received timely buprenorphine, naltrexone, or methadone treatment. A marked difference was observed by age, with only 4.7% of adolescents receiving an OUD medication compared with 26.9% of young adults. Receipt of each of the 3 OUD medications was independently associated with enhanced retention. Compared with youths who received only behavioral health services, those receiving buprenorphine were 42% less likely to discontinue treatment during the follow-up period, those receiving naltrexone were 46% less likely to discontinue treatment during the follow-up period, and those receiving methadone were 68% less likely to discontinue treatment during the follow-up period.

Retention in care is critical to successful treatment of addiction and is increasingly being adopted as a quality measure.26,35,36,37,38,39,40 In treatment protocols and clinical trials, eliminating or reducing substance use has traditionally been the primary end point.41 However, increasing mortality from overdose and the recognition that addiction is a chronic, relapsing condition have prompted clinicians, researchers, and policy makers to increasingly focus on retention in care.6,41 Even when patients do not reduce their substance use, individuals engaged and retained in care can receive harm-reduction services and treatment of comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions.42,43,44 The advantage of this approach is supported by a recent, large meta-analysis, which found that, among adults, remaining in treatment is associated with substantially reduced all-cause mortality and mortality from overdose.15

Our findings reveal a critical gap in quality of care for youths, with only a minority who seek medical attention receiving the evidence-based OUD medications recommended by multiple national treatment guidelines.5,6,7,8 Furthermore, this poor deployment of timely OUD medication may place youths at risk for early discontinuation of treatment. Our results build on the findings of the only 3 randomized clinical trials of OUD medications among youths conducted to date.20,21,22 These randomized clinical trials showed improved treatment outcomes, including short-term enhanced retention in care, among youths who received buprenorphine under experimental conditions. We found that not only buprenorphine but also naltrexone and methadone, when provided in real-world treatment settings, were associated with enhanced retention in care compared with receipt of behavioral health services alone. Because clinical follow-up in randomized clinical trials of youths to date has ranged from only 28 days to 12 weeks,20,21 our results also suggest that OUD medications may contribute to enhanced retention in care persisting beyond the time frames previously studied.

Strategies to enhance access to OUD medications for youths are urgently needed.1,9,45 Our study sample included only youths who presented for medical attention, a group comprising only a minority of the true population of youths with OUD.6 Youths encounter substantial barriers to accessing OUD medications, including insufficient pediatric prescribers, poor familiarity with medications among clinicians, systemic barriers to accessing methadone, and stigma surrounding medication use.1,9,10,11 At many treatment programs, youths may be denied OUD medications owing to their younger age, or paradoxically, if they are receiving an OUD medication prescribed elsewhere, use of such medications may preclude entry into treatment.11 As of January 2018, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Treatment Locator lists 1765 addiction treatment programs for adolescents or young adults, among which only 37% prescribe OUD medications, and of the remaining programs, 43% deny admission to youths receiving OUD medications prescribed elsewhere.46 Our findings suggest that the practice of limiting access to OUD medications for youths may be detrimental for addiction treatment programs because receipt of medication is associated with enhanced retention in care.

We observed differences by race in access to OUD medications. In 1 recent study of youths with private health insurance, black youths were 42% less likely to receive buprenorphine or naltrexone for OUD compared with white youths,1 which is consistent with our finding that black youths were 49% less likely to receive OUD medications. More important, we did not observe any differences in retention in care according to race after controlling for receipt of medications. Therefore, amid national efforts to expand access to evidence-based treatment, it is crucial that policy makers address the national treatment gap in a way that improves, rather than exacerbates, the disparities that we observed.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, owing to the observational nature of our study, we are unable to conclusively determine whether the enhanced retention in care that we observed was attributable to the OUD medications themselves or to the clinical systems in which they were provided. For example, methadone is typically administered in a setting with strict rules and regulations that may promote greater adherence for patients who receive such treatment.47 Similarly, provision of evidence-based medications such as buprenorphine or naltrexone could be more common in treatment centers with higher-quality standards.38,39 Second, we found that receipt of behavioral health services alone was associated with poorer retention in care than was treatment with OUD medication, but the behavioral health services that we included were diverse. Although we adjusted for level of care, we cannot exclude the possibility that some behavioral health services may have been highly effective but were categorized with less effective behavioral health services.

Third, although we adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of youths, we cannot exclude the potential influence of unmeasured confounders. In particular, given the administrative nature of the data, we were unable to adjust for severity of OUD, and youths with more severe OUD may have been more likely to receive medication as well as added resources to maximize retention. Fourth, we were unable to identify buprenorphine used in detoxification settings, which when rapidly tapered, may be associated with poorer retention in care compared with longer-term buprenorphine maintenance treatment.20 Because only 3.0% of youths (97 of 3247) in the study sample received detoxification services, this potential limitation is unlikely to have had a substantial association with the effect sizes that we observed.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first large study to examine receipt of each of the 3 evidence-based OUD medications among youths. We are also unaware of other large studies that have examined retention in care in association with timely OUD medication treatment for youths. The finding that medications were provided to only approximately 1 of 4 youths presenting for care overall, including only 1 of 21 adolescents, highlights a crucial potential opportunity to improve OUD care and enhance retention in treatment. As deaths from overdose increase among US youths, it is vital that clinicians, researchers, and policy makers ensure that access to evidence-based OUD medications for young people remains a national priority.

eFigure. Flowchart for Development of Analytic Sample

eTable 1. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) Codes Used to Identify Utilization

eTable 2. National Drug Codes Used to Identify Pharmacy Claims for OUD Medications

eTable 3. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) Diagnosis Codes for Medical and Psychiatric Comorbidity

eTable 4. Time to Receipt of Any Treatment (ie, Behavioral Health Services or OUD Medication) or of Any OUD Medication (Buprenorphine, Naltrexone, or Methadone) After Diagnosis: January 1, 2014, to September 30, 2015

eTable 5. Characteristics of 1139 Youth Who Received Timely OUD Medication According to Pharmaceutical Received

References

- 1.Hadland SE, Wharam JF, Schuster MA, Zhang F, Samet JH, Larochelle MR. Trends in receipt of buprenorphine and naltrexone for opioid use disorder among adolescents and young adults, 2001-2014. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):747-755. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1195-1201. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtin SC, Tejada-Vera B, Warner M Drug overdose deaths among adolescents aged 15–19 in the United States: 1999-2015. NCHS data brief no 282. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤30 years—Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):453-458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee on Substance Use and Prevention Medication-assisted treatment of adolescents with opioid use disorders. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161893. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Dept of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction: Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358-367. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feder KA, Krawczyk N, Saloner B. Medication-assisted treatment for adolescents in specialty treatment for opioid use disorder. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(6):747-750. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CHA, Catlin M, Larson EH. Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid use disorder. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):23-26. doi: 10.1370/afm.1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagley SM, Hadland SE, Carney BL, Saitz R. Addressing stigma in medication treatment of adolescents with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2017;11(6):415-416. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas CP, Fullerton CA, Kim M, et al. Medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):158-170. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506-1513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell J, Trinh L, Butler B, Randall D, Rubin G. Comparing retention in treatment and mortality in people after initial entry to methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Addiction. 2009;104(7):1193-1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02627.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupouy J, Palmaro A, Fatséas M, et al. Mortality associated with time in and out of buprenorphine treatment in French office-based general practice: a 7-year cohort study. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(4):355-358. doi: 10.1370/afm.2098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuman-Olivier Z, Weiss RD, Hoeppner BB, Borodovsky J, Albanese MJ. Emerging adult age status predicts poor buprenorphine treatment retention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;47(3):202-212. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein ZM, Kim HW, Cheng DM, et al. Long-term retention in office based opioid treatment with buprenorphine. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;74:65-70. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dreifuss JA, Griffin ML, Frost K, et al. Patient characteristics associated with buprenorphine/naloxone treatment outcome for prescription opioid dependence: results from a multisite study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):112-118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsch LA, Moore SK, Borodovsky JT, et al. A randomized controlled trial of buprenorphine taper duration among opioid-dependent adolescents and young adults. Addiction. 2016;111(8):1406-1415. doi: 10.1111/add.13363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2003-2011. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsch LA, Bickel WK, Badger GJ, et al. Comparison of pharmacological treatments for opioid-dependent adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1157-1164. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Schuster J, Farmer C. The impact of buprenorphine on treatment of opioid dependence in a Medicaid population: recent service utilization trends in the use of buprenorphine and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(1-3):72-78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garnick DW, Lee MT, O’Brien PL, et al. The Washington circle engagement performance measures’ association with adolescent treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):250-258. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Society of Addiction Medicine ; Mee-Lee D, ed. The ASAM Criteria: Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance-Related, and Co-Occurring Conditions. 3rd ed Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris AHS, Ellerbe L, Phelps TE, et al. Examining the specification validity of the HEDIS quality measures for substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;53:16-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohlman MK, Tanzman B, Finison K, Pinette M, Jones C. Impact of medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction on Medicaid expenditures and health services utilization rates in Vermont. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;67:9-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frazier W, Cochran G, Lo-Ciganic W-H, et al. Medication-assisted treatment and opioid use before and after overdose in Pennsylvania Medicaid. JAMA. 2017;318(8):750-752. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp#overview. Published March 2017. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- 30.Bardach NS, Coker TR, Zima BT, et al. Common and costly hospitalizations for pediatric mental health disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):602-609. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prescription drug overdose data & statistics: guide to ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 codes related to poisoning and pain. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pdo_guide_to_icd-9-cm_and_icd-10_codes-a.pdf. Revised August 12, 2013. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- 32.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299(1):70-78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(1):39-47. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Evaluating the proportional hazards assumption In: Kleinbaum DG, Klein M, eds. Survival Analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:161-200. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6646-9_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris AHS, Humphreys K, Bowe T, Tiet Q, Finney JW. Does meeting the HEDIS substance abuse treatment engagement criterion predict patient outcomes? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2010;37(1):25-39. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9142-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, et al. Collaborative care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: the SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1480-1488. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou R, Korthuis PT, Weimer M, et al. Medication-assisted treatment models of care for opioid use disorder in primary care settings. Technical brief no. 28. (prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-Based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2015-00009-I). AHRQ Publication No. 16(17)-EHC0. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. [PubMed]

- 38.Carroll KM, Weiss RD. The role of behavioral interventions in buprenorphine maintenance treatment: a review. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(8):738-747. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Society for Addiction Medicine The ASAM Performance Measures For the Addiction Specialist Physician. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society for Addiction Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.New York State Department of Health Medicaid redesign team (MRT) behavioral health reform work group final recommendations. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/docs/mrt_behavioral_health_reform_recommend.pdf. Published October 15, 2011. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- 41.Uchtenhagen A. Commentary on Metrebian et al (2015): what is addiction treatment research about? some comments on the secondary outcomes of the Randomized Injectable Opioid Treatment Trial. Addiction. 2015;110(3):491-493. doi: 10.1111/add.12821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Kretsch N, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):425-431. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakeman SE. Another senseless death—the case for supervised injection facilities. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1011-1013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1613651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saloner B, Feder KA, Krawczyk N. Closing the medication-assisted treatment gap for youth with opioid use disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):729-731. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Map—SAMHSA behavioral health treatment services locator. https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/locator. Accessed February 26, 2018.

- 47.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Wachino V, Hyde PS Coverage of behavioral health services for youth with substance use disorders. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib-01-26-2015.pdf. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed December 1, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flowchart for Development of Analytic Sample

eTable 1. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) Codes Used to Identify Utilization

eTable 2. National Drug Codes Used to Identify Pharmacy Claims for OUD Medications

eTable 3. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) Diagnosis Codes for Medical and Psychiatric Comorbidity

eTable 4. Time to Receipt of Any Treatment (ie, Behavioral Health Services or OUD Medication) or of Any OUD Medication (Buprenorphine, Naltrexone, or Methadone) After Diagnosis: January 1, 2014, to September 30, 2015

eTable 5. Characteristics of 1139 Youth Who Received Timely OUD Medication According to Pharmaceutical Received