Abstract

Patients with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) commonly experience psychological distress post-implantation, but physiological stress and differences by implant strategy remain unstudied. This study describes indicators of physiological (salivary cortisol, C-reactive protein, sleep quality) and psychological (perceived stress, depression, fatigue) stress by implant strategy and examines relationships between stress and outcomes (quality of life [QOL] and functional status). Prospective, cross-sectional data was collected from patients ≥3 months post-LVAD (N=44) and descriptive statistics and logistic regression were used. The study sample was average age 57.7± 13 years, mostly male (73%), married (70.5%) and racially diverse. Median LVAD support was 18.2 months. Most had normal cortisol awakening response and fair sleep quality, with moderate psychological stress. There were no differences in stress by implant strategy. Normal cortisol awakening response was correlated with low depressive symptoms. Sleep quality and psychological stress were associated with QOL, while cortisol and CRP levels were associated with functional status. This is the first report of salivary biomarkers and stress in LVAD outpatients. Future research should examine physiological and psychological stress and consider potential clinical implications for stress measurement for tailored approaches to stress management in this population.

Keywords: heart failure, LVAD, stress, outcomes

Background

As heart failure (HF) prevalence approaches 6.5 million in the United States, left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) help advanced HF patients live longer than medicine alone.1,2 LVADs are placed as a bridge to transplant (BTT) or ‘destination therapy’ (DT), meaning that it is expected that the patient will be supported by the LVAD until death. Following LVAD implant, emotional distress and psychological sequelae have been reported, although preliminary evidence suggests that BTT and DT patients experience stress in distinct ways.3,4 Importantly, psychological stress response in cardiac patients in general has been associated with poor health outcomes and reduced physical activity, both critical considerations in LVAD.5,6

When the brain perceives a stressful event, it stimulates both physiological and psychological responses.5 From a physiological perspective, actual or interpreted threats to an individual’s homeostatic balance initiate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis secretion of glucocorticoids, which mobilizes fight-or-flight responses.7 Notably, increased cortisol is an independent predictor of mortality and cardiac events in HF patients,6 and although unloading of the left ventricle with LVAD support may result in decreased myocardial stress and inflammation, inflammatory biomarkers of chronic stress (e.g. C-reactive protein [CRP]) remain elevated post-implant.8 Additionally, neurohormonal activity is intrinsically connected to sleep; many neurohormones vary with the diurnal cycle. Thus, sleep quality is also an important indicator of physiological stress, and is particularly poor among HF patients in general and VAD patients in particular.9,10 From a psychological perspective, subjectively reported responses such as depression, fatigue, and general perceived stress are substantial in LVAD patients and may vary by implant strategy. 3,4,11

Together, stress biomarkers, sleep quality, perceived stress, depression, and fatigue are indicators of physiological and psychological stress, and likely influence important clinical and person-centered outcomes. However, few studies have examined these relationships in the LVAD population. Research in this area will inform researchers’ and clinicians’ understanding and ability to identify patients at particularly high risk for elevated post-implant stress response and subsequently impact on critical LVAD outcomes such as quality of life (QOL) and functional status. Importantly, there are substantial, poorly understood disparities in QOL and health outcomes between transplant eligible and ineligible patients12 which must be elucidated to better inform both implant strategy decision-making and post-implant management, particularly of DT patients. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe physiological and psychological stress by implant strategy and to examine relationships among physiological stress response (cortisol, CRP and sleep quality), psychological stress response (perceived stress, depression and fatigue) and outcomes (QOL and functional status).

Methods

Study Design

For this cross-sectional study, we focused on the psychological and physiological aspects of stress. Patients living with LVAD and served by the LVAD clinic at two tertiary care centers in the Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan area were included in the study. Our conceptual framework (figure 1) was based on the Allostatic Load Model, which posits that psychological, behavioral and physiological influences result in the burden of stress patients experience.13 Institutional Review Boards at both institutions approved this study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework

Sampling

Convenience sampling was used to recruit patients living with an LVAD from both centers. We recruited individuals from the outpatient clinic setting after they had been seen in the LVAD clinic at least once post-implantation. Patients met inclusion criteria if they: were over 21 years of age, had a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score ≥17 (mild to no cognitive impairment), and could speak and understand English. A MoCA score ≥ 17 was used so that only patients who can reliably self-report were included.14 Patients were not seen during acute hospitalizations and no proxies were used for the completion of survey data.

Measurement

LVAD patients’ stress response was investigated using both physiological and psychological data (figure 1). Physiologic stress response was measured by salivary biomarkers and a sleep survey. Psychological stress response was measured by validated instruments addressing perceived stress, depression and fatigue. In addition, participant demographics and medical characteristics were collected via medical chart review.

Physiological Stress Response

Salivary Biomarkers

Cortisol and C-reactive protein (CRP) salivary specimens were collected by participants in their home. Cortisol changes with the diurnal rhythm, with normal cortisol awakening response defined as salivary cortisol levels that peak 30 minutes after waking, followed by a trough in the evening which drops below waking levels.15,16 Additionally, cortisol can vary significantly based on acute stressors. Because of the interplay between acute response and the diurnal cycle, cortisol awakening response is a more accurate representation of HPA activation than an absolute cortisol level, as absolute cortisol levels are difficult to interpret.17 Therefore participants were asked to collect 3 samples per day for 2 days on days when they expected to have a ‘normal’ routine. Samples were collected at waking, 30 minutes after waking and prior to going to bed. Participants documented time and date of sample collection along with a short log of what was happening at the time of each sample collection. Specimens were frozen to protect against enzymatic action and bacterial growth.

Samples for salivary cortisol and CRP were aliquoted into separate tubes and labeled for freezing at −20°C until batch assayed in duplicate for the respective measurements. Saliva samples were measured using enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits from Salimetrics (St. College, PA). The intra-assay coefficient of variation was less than 6% for levels of cortisol and 10% for CRP. Plates were read using a Packard Spectra Count microplate photometer.

Sleep Quality

Sleep Quality was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), a 19-item instrument measuring seven domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medications, and daytime dysfunction over the last month. A global score is calculated from the 7 domains, with a cutoff score of 5 indicating poor sleep quality (higher scores indicate worse sleep quality) and has good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83).18

Psychological Stress Response

Perceived Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) contains 10 items and is a general measure of the cognitive appraisal and perceptions of stress over the last month. There are no diagnostic cutoffs for this instrument; scores range from 0–40 with higher scores indicating worse stress (Cronbach’s alpha 0.82).19

Depression

The Perceived Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a 9-item, well-validated scale that measures depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha 0.89).20,21 A total score of 5 represents mild depressive symptoms. There is also a screen for suicidality.

Fatigue

The Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF) uses a Likert scale to measure 4 dimensions of fatigue: severity, distress, interference with ADLs and timing.22 The instrument is 16 items and is validated in chronic conditions (Cronbach’s alpha 0.93).9,22

Outcomes

Quality of life

The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-12) measures four domains of QOL: physical limitation, symptoms, QOL, social limitation. High QOL was defined as >75 on the overall score, based on literature relating this cutoff to the highest cardiac event-free survival.23

Functional status

The Six Minute Walk (6MWT) is a non-invasive, valid and reliable test of functional status at submaximal level (Reliability: 0.86).24 High Functional status was defined as 6MWT distance > 300m, based on literature supporting worse outcomes below this threshold.25

Attrition and Sample Size

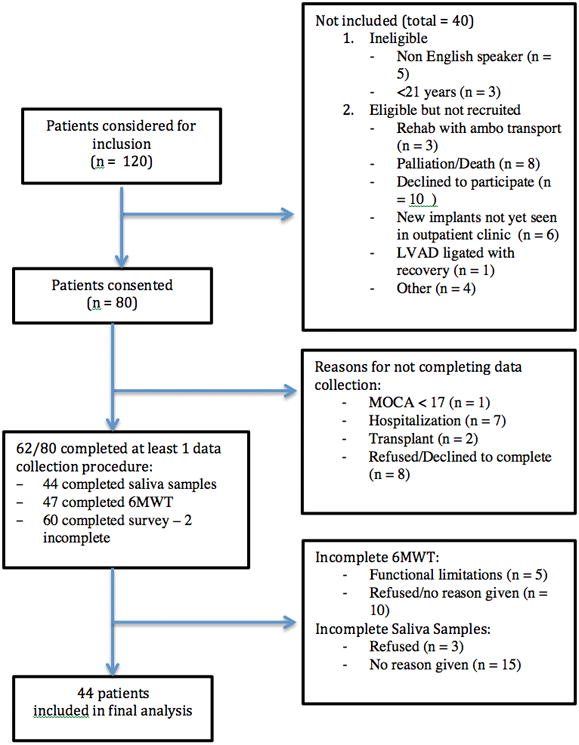

While the data collected was essentially cross-sectional, participants were required to have a minimum of 2 days to complete the salivary biomarker sample collection protocol alone. Despite multiple attempts for follow-up there was a 22% rate of attrition from this study, explained in Figure 2. Of those who completed the survey, 71% completed salivary sample collection. There were no statistically significant differences in key demographic variables between those who completed and those who did not complete all study procedures.

Figure 2.

STROBE diagram Study Inclusion, Attrition and Sample Size

Data analysis

Data were checked for completeness, quality and consistency. Appropriate graphical displays, frequency (percent) for categorical variables, and mean (standard deviation) or median (Intraquartile range) for continuous variables were used for data summary. Change in cortisol was summarized by calculating the area under the curve by using the mean of the cortisol level for each sample for day 1 and day 2. Non-parametric tests (including Mann-Whitney two group comparisons) were used to examine the difference between implant strategy groups for continuous variables; categorical data comparisons were done using Chi-square tests. A Spearman’s rank correlation matrix was created to examine relationships between continuous psychological and physiological stress variables. Bivariate logistic regression modeling was used to explore relationships between physiological and psychological stress and dichotomized outcomes (high QOL [KCCQ>75] and high functional status [6MWT>300M]). All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) with two-sided alpha of 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

The characteristics of the sample (N = 44) are reported in Table 1. Patients were, on average, 57.7 ± 13 years of age, male (73%), white (45.5%) and married (70.5%). This sample of LVAD patients from 2 centers was similar to the overall LVAD population in distribution of age and gender, but was more racially diverse.26,27 The percentage of LVAD patients who had been implanted emergently (Intermacs profiles 1 or 2) was 59%, slightly above the current Intermacs reported rate of 52%.27 Most patients had been managing their device for more than a year: median time since implant in the overall sample was 18.2 months, with 6 participants managing their LVAD for more than 4 years. Typical co-morbidity profiles were noted, 34% diabetes, 27% chronic renal disease and 9% had a history of depression. Most participants were implanted with a Heartmate II device (63.6%); more DT patients had a Heartmate II in this sample (p< 0.02). Two patients were implanted with Heartmate III through the Momentum trial. DT patients had their device about twice as long as BTT patients (35 months vs. 17 months, p< 0.02). Both BTT and DT patients had few recent hospitalized days with no significant difference between groups, however both groups had large variability (median 1, IQR 0–14.5). There were no significant differences between BTT and DT groups for demographic characteristics including gender, age, race, marital status, income and education.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Implant Strategy Implant

| Implant Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=44) %(n) or Median (IQR) | BTT (n = 24) % (n) or Median (IQR) | DT (n = 20) % (n) or Median(IQR) | Mann-Whitney U or Chi2 p-value | |

| Gender (Male) | 73% (32) | 36% (16) | 36% (16) | 0.32 |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 59.5 (50–65) | 59.2 (48–62) | 63.4 (52–72) | 0.16 |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White | 45% (20) | 20% (9) | 25% (11) | |

| Black | 43% (19) | 30% (13) | 14% (6) | 0.27 |

| Other | 11% (5) | 5% (2) | 7% (3) | |

|

| ||||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married or Living with Partner | 70% (31) | 43% (19) | 27% (12) | 0.17 |

| Other | 29% (13) | 11% (5) | 18% (8) | |

|

| ||||

| Annual Household Income | ||||

| < $30,000 | 25% (11) | 9% (4) | 16% (7) | |

| $30, 000–60,000 | 15% (7) | 7% (3) | 9% (4) | 0.21 |

| >$60,000 | 60% (26) | 39% (17) | 20% (9) | |

|

| ||||

| Highest Level of Education | ||||

| <= high school | 26% (11) | 11% (5) | 14% (6) | |

| technical school or some college | 28% (12) | 14% (6) | 14 % (6) | 0.52 |

| graduated college or beyond | 46% (20) | 30% (13) | 16% (7) | |

|

| ||||

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| Diabetes | 34% (15) | 14% (6) | 20 % (9) | 0.16 |

| Chronic Renal Disease | 27% (12) | 11% (5) | 16% (7) | 0.29 |

| Depression | 9% (5) | 5% (2) | 7% (3) | 0.49 |

| PulmHTN/RightHF | 9% (5) | 5% (2) | 7% (3) | 0.85 |

|

| ||||

| Emergent Implant (Intermacs Profile 1 or 2) | 59% (26) | 32% (14) | 27% (12) | 0.90 |

|

| ||||

| Months since implant | 18.2 (6–34) | 11.4 (4–25) | 30.7 (12–47) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Complications after VAD | ||||

| GI bleed | 27% (12) | 11% (5) | 16% (7) | 0.29 |

| Stroke | 21% (9) | 7% (3) | 14% (6) | 0.76 |

| Driveline Infection | 16% (7) | 5% (2) | 11% (5) | 0.13 |

| RHF | 3% (1) | 0% (0) | 2% (1) | 0.27 |

| Re-implant | 3% (1) | 0% (0) | 2% (1) | 0.27 |

| Sepsis | 7% (3) | 2% (1) | 5% (2) | 0.45 |

| Trach | 5% (2) | 2% (1) | 2% (1) | 0.90 |

| Days Hospitalized in the last 6 months or since implant | 1 (0–14.5) | 1 (0–15) | 1 (0–14) | 0.81 |

Descriptive Findings

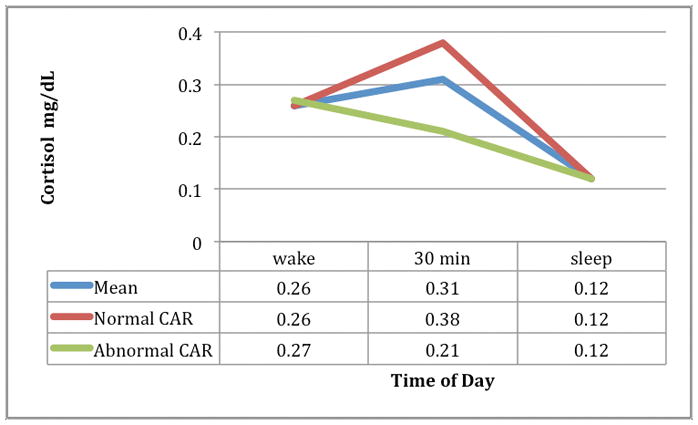

Physiological and psychological stress response and QOL and functional status outcomes are presented in Table 2. For our samples, the intra-assay coefficient of variation was less than 6% for levels of cortisol, and less than 10% for CRP. Most participants (61%, n = 27) had a normal cortisol awakening response (Figure 3). Mean area under the curve for the overall group was 322.3 ± 225; mean salivary CRP was 1196 ± 823 pg/mL. As aggregates, these values represent low but highly variable salivary cortisol and CRP values, however there is little comparison in the literature.28

Table 2.

Physiological Stress, Psychological Stress and Outcomes by Implant Strategy

| Overall | Implant Strategy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=44) Mean± SD | (n=44) Median (IQR) | BTT (n = 24) Median(IQR) | DT (n = 20) Median(IQR) | Mann-Whitney U or Chi2 p-value | |

| Physiological Stress: Biomarkers | |||||

| Cortisol (μg/dL) | |||||

| Waking | 0.26 ± 0.12 | 0.23 (.19–.33) | 0.21 (.16–.25) | 0.29 (.21–.38) | 0.03 |

| 30 minute after waking | 0.31 ± 0.18 | 0.30 (.19–.42) | 0.29 (.19–.40) | 0.30 (.21–.46) | 0.55 |

| Bedtime | 0.12 ± 0.11 | 0.08 (.05–.13) | 0.08 (.05–.11) | 0.10 (.05–.18) | 0.37 |

| Area under the curve | 322.3 ± 226 | 263.7 (179–419) | 253.7 (181–363) | 271.5 (176–470) | 0.45 |

| C-reactive protein (pg/mL) | 1196 ± 823 | 1003.6 (479–1654) | 1329.9 (306–2135) | 980.6 (518–1433) | 0.63 |

| Physiological Stress: Sleep Quality | |||||

| Global sleep quality (0 = best - 21 = worst) | 6.2 ± 3.5 | 5.5 (3–8.5) | 6 (3–8) | 5 (3.5–9.5) | 0.81 |

| Psychological Stress | |||||

| Perceived Stress Scale (0 = no stress – 40 = maximum) | 11.8 ± 7.0 | 12 (6–18) | 12 (6–17) | 11.5 (6–18) | 0.93 |

| Depression PHQ-9 (0 = No symptoms – 10 = maximum depressive symptoms) | 3.4 ± 3.8 | 2 (1–5) | 2 (.5–4) | 2.5 (1–5.5) | 0.46 |

| Fatigue MAF total (1 = no fatigue – 50 = severe fatigue) | 15.1 ± 8.7 | 16.6 (11–21) | 18.5 (11–21) | 14.3 (12–20) | 0.46 |

| Quality of Life | |||||

| KCCQ Overall (0 = poor – 100 = excellent QOL) | 73.0 ± 13.5 | 74.6 (66–82) | 75.6 (66–82) | 71.0 (65–81) | 0.44 |

| Hi QOL (>75) %(n) | 48% (21) | 50% (12) | 45% (9) | 0.74 | |

| Functional Status | |||||

| 6 Minute Walk Test Distance (meters) | 337.9 ± 162 | 368.1 (275–440) | 367.3 (274–432) | 374.9 (278–453) | 0.87 |

| Hi 6MWT (>300m) %(n) | - | 68%(30) | 67% (16) | 70% (14) | 0.81 |

Figure 3. Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR).

Mean Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR) N = 44

Normal CAR n = 27

Abnormal CAR n = 17

Overall, LVAD patients experienced poor sleep quality and among psychological stress response variables, LVAD patients reported moderate levels of perceived stress, mild depressive symptoms, and moderate fatigue. Similar to salivary cortisol and CRP values, there was substantial variability around psychological stress indicators in the sample.

In this sample, LVAD patients’ QOL approached the “high” cutoff on average (KCCQ>75). Average walking distance on the 6MWT was greater than 300 meters, the threshold used to indicate lower risk of adverse events.25

Physiological and Psychological Stress by Implant Strategy

Physiological stress as measured by cortisol level, CRP and sleep quality did not differ by implant strategy, except in waking cortisol level, which was higher in DT patients (p < 0.03). There were no significant differences in perceived stress, depression or fatigue by implant strategy. Finally, there were also no differences by implant strategy in outcomes: overall QOL or 6MWT distance.

Relationships between Physiological, Psychological Stress and Outcomes

When comparing those with normal versus abnormal cortisol awakening response, Chi2 testing showed significant relationships between normal cortisol awakening response and low levels of depressive symptoms (p< 0.02, Figure 4). No other significant associations were found between the physiological variables themselves (cortisol, CRP, sleep quality), or between physiological and psychological variables. Further, in bivariate analysis, cortisol mean AUC was positively associated with 6MWT distance (p< 0.01), however the odds ratio and standard error were extremely small. Cortisol and QOL were not significantly associated (p< 0.07). Worse sleep quality and psychological stress response (including perceived stress, depression and fatigue) were associated with worse QOL (p< 0.05), but not with 6MWT.

Figure 4.

Relationships between Cortisol Awakening Response and Depressive Symptoms

Discussion

Examination of physiological and psychological stress response variables among community-dwelling LVAD patients revealed no significant differences in physiological or psychological stress response by implant strategy, although this is likely a function of sample size. We did see a relationship between normal cortisol awakening response and low levels of depression, however. Also, higher salivary cortisol AUC levels were related to improved functional status with a trend towards improved QOL. In addition, poor sleep quality and psychological stress response variables (perceived stress, depression and fatigue) were each related to QOL. These findings are novel in the LVAD population, and therefore contribute to a deeper understanding of how LVAD patients may respond to stress. This provides an important foundation for the feasibility of future biobehavioral stress research in LVAD, particularly given that these relationships were still present despite this small and heterogeneous sample of complex patients.

The finding of similar stress levels for BTT and DT patients was surprising, as the literature points to unique difficulties faced by each group.3 In particular, we expected to see a difference by implant strategy because of the inherent differences that result in a DT patient being ineligible for transplant (e.g. age, comorbidities), as well as the longer duration of support among our DT participants as compared to our BTT participants. Sample size and cross-sectional design, most notably the inclusion of participants at different points in the post-implant trajectory, likely precluded us from detecting significant differences between BTT and DT patients, and prevented comprehensive adjustment for confounders. What this study does provide is important support for the feasibility and acceptability of collecting biobehavioral stress data in this population, an early understanding of what stress levels may be on average, and insights into which factors should be included or controlled in future research with larger samples.

Additionally, it may be that distinct implant strategy-related stressors are associated with variables not measured in this study, such as hope related to transplant, existential distress, or clinical factors such as adverse events or medications.3,4 Stress and coping may also differ by implant strategy at the time of decision, but less after the patients have adapted to the decision.4,29 However, there is still a need to further explore how implant strategy relates to stress and coping and when these differences are most apparent. For example, previous studies have suggested that the uncertainty in decision-making is very stressful and higher stress may be present at decision points in LVAD care such as implant and after adverse events.4,29 Adjustment to home after a long hospitalization may also be particularly difficult for LVAD patients and caregivers, but after home routines are established, living with an LVAD becomes less challenging for most.3

Regardless of whether differences exist in physiological and psychological stress by implant strategy, this study confirms that self-reported stress has a significant role in LVAD patient QOL outcomes, and that there is a relationship between depression and cortisol in LVAD patients. Importantly, since our results demonstrate that stress indicators are associated with outcomes across implant strategies, BTT and DT patients alike should be assessed for signs and symptoms of poor stress response after implant. Although sample averages for the stress indicators measured in this study may suggest acceptable levels of stress, the substantial variability found in these measures should be considered. Heterogeneity in post-LVAD person-centered outcomes is a common finding, underlining the need for standardized psychosocial assessment in the clinical setting.29 Standardized assessment is likely needed for the duration of LVAD support, given that it is difficult to predict when patients may reach a “tipping point” that could impact their overall health and QOL. Although many implanting centers may already implement some type of post-LVAD psychosocial assessment, there is no nationally accepted standard apart from that collected during INTERMACS participation. As such, there is an imminent need for multidisciplinary, multi-center collaboration to support the development and implementation of a robust psychosocial assessment standard of practice for use in the outpatient VAD setting.

Normal cortisol awakening response (present in the majority of patients) was associated with low levels of depression in the study sample. This relationship is consistently demonstrated in the literature,17 and this corroboration serves as a reminder to healthcare providers that improving psychological symptoms may also improve physiological measures. In healthy older adults abnormal cortisol awakening response, characterized by a decrease in cortisol 30 minutes after waking, has been associated with increased depression and decreased QOL, however we did not see a relationship between abnormal cortisol awakening response and QOL.17 Similarly, cortisol levels are associated with poor sleep quality in other populations, however we did not see this relationship in our sample.30,31 The lack of relationship between cortisol and QOL may be a function of sample size given the trend toward significance (p=0.07), however more work is needed to understand the relationships among cortisol, sleep quality and QOL among LVAD patients.

Overall sleep quality was particularly compromised in this sample, exceeding the cutoff for poor sleep quality on the PSQI. In fact, patients reported 2 sleep disturbances per night on average. These sleep disturbances may be more disruptive for LVAD patients than other populations. If an LVAD patient wakes, they may do a quick equipment check or require a change from AC power to battery power to get up to use the bathroom. Poor sleep quality among a small (n=12), exploratory study of LVAD patients has been reported previously, and sleep disruption and poor sleep quality among general HF patients have been associated with significantly lower odds of cardiac-event-free survival compared to those with good sleep quality.10,35 Given these findings, LVAD patients with poor sleep may also be at risk, however more prospective research is needed to examine sleep, survival and other outcomes in this population.

Implications for Clinical Practice

The significant relationships between sleep quality, perceived stress, depression, fatigue and QOL provide an important insight into the patient experience of LVAD therapy. Individuals experiencing higher levels of psychological stress and sleep quality experience worse quality of life. Supportive care for those that have difficulty managing stress related to treatment, mood and outside pressures such as finances is critical. It also highlights the need to provide high quality mental health assessment both prior to and after implant so that appropriate mental health services can be provided throughout the continuum of care. Patients and families may also find support in connecting with a network of other LVAD patients and caregivers.36 Some programs provide support groups where patients and caregivers can meet together to discuss the unique challenges of managing the stress of living with an LVAD. In addition, online groups on Facebook and websites like myLVAD.com provide forums for patient engagement. However, peer support is not an adequate replacement for formal psychological health services: formal assessment and clinical therapies to support mental and emotional health during LVAD are clearly warranted.37

In terms of the utility of biomarker measurement in the assessment of psychological stress, salivary cortisol is not typically used diagnostically or prognostically in HF.35 It should also be noted that the measurement of salivary cortisol, including multiple samples that must be collected and appropriately stored at precise times during the day, can be burdensome for patients, and the raw data can be analytically challenging. For these reasons, at this time we do not recommend implementing salivary cortisol measurement clinically in LVAD clinics using this methodology, but multisite research with larger samples may change this paradigm. Given the stated limitations of salivary biomarkers, we recommend that measurement of salivary biomarkers in this population should only be done in conjunction with questionnaire screening for depression and high levels of stress, as well as the other mental health, peer, and supportive care interventions noted above. Alternatively, a single swab might be a more practical approach that presents less burden for patients and is useful in measuring salivary amylase and CRP.35,36 Additionally, recent studies have shown promise examining serum biomarkers including oxidative stress, BNP and cytokines; adding these tests as appropriate to regularly scheduled blood draws is unlikely to cause undue burden for LVAD patients.32–34

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including prospective design, recruitment from multiple sites with racial diversity, and a biobehavioral approach to considering stress among LVAD patients. This study provides a snapshot of the stress managed by chronic LVAD patients living in the community and being treated in outpatient LVAD clinics. It is the first to incorporate inflammatory stress salivary biomarkers with measures of psychological stress in the LVAD population. We have demonstrated that BTT and DT patients experience similar levels of stress, but questions remain about when differences between implant strategy groups may impact outcomes, and comparisons using larger samples are warranted. Additionally, comparing stress in HF patients with and without LVAD may provide valuable insights. Future work should also include longitudinal methods to evaluate the role of stress and sleep quality using a biobehavioral approach, as integration of physiological biomarkers and psychological measures over time may help elucidate the substantial variability in post-LVAD clinical trajectories.

This study has limited generalizability due to its limited sample size, which precludes adjusted analyses for variables such as duration of support, health status, and other clinical variables such as medications. Furthermore, patients were not excluded based on recent hospitalization, and hospitalization or other acute events immediately prior to data collection may have impacted physiological stress indicators. Sample size also precluded comparisons of stress by gender, which is an important consideration for future research in this population, given that gender is known to influence the experience of stress and interactions between stress and health.38 In addition, socioeconomic factors such as social support and financial duress may impact stress in ways that this study was not powered to detect, and thus also remain important avenues for future research.39,40 Notably, LVAD centers often struggle to make meaningful research contributions due to the small LVAD populations that are served. To address this we recruited from 2 LVAD centers. It is possible that study attrition was a function of illness and/or stress that was not captured, which may have made salivary sample collection too burdensome for some participants. To mitigate this, the study team picked up samples from participants’ homes; still, about one third of those who consented did not complete salivary collection. Also, because we did not include patients hospitalized, at rehab centers, or in the first 2 months after implant, we likely did not capture certain stress profiles in the LVAD population. However, since much of the focus in the LVAD literature has been around the response to implant, we have provided an important contribution to our understanding of the role of stress in the community dwelling LVAD population.

Conclusion

This study reveals important links between physiological and psychological stress response and outcomes among LVAD patients. We did not find differences by implant strategy for any of our variables of interest, suggesting that LVAD patients experience similar levels of stress regardless of implant strategy. This was also the first study to examine salivary biomarkers in this population, and we identified relationships between cortisol, depression and outcomes. Furthermore, our work provides new insight into the significant role of sleep quality in LVAD patient physical and psychological health. Finally, links in sleep quality, psychological stress response, and quality of life may point to the utility of examining stress profiles in tailoring mental health interventions for particularly at-risk patients.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Bivariate Logistic Regressions of Quality of Life and Functional Status

| Odds Ratio | SE | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome 1: Quality of Life (Hi QOL >75) | ||||

| Predictor | ||||

| Cortisol (mean AUC) | 1.003 | 0.002 | 0.07 | .99–1.01 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.00 | <0.001 | 0.89 | .99–1.00 |

| Sleep Quality | 0.79 | 0.1 | 0.02 | .65–.97 |

| Perceived Stress | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.01 | .79–.97 |

| Depression | 0.80 | 0.09 | 0.04 | .64–.99 |

| Fatigue | 0.86 | 0.05 | <0.01 | .78–.95 |

| Outcome 2: Functional Status (Hi 6MWT >300m) | ||||

| Predictor | ||||

| Cortisol (mean AUC) | 1.01 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 1.00–1.00 |

| C-reactive protein | 1.00 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 1.00–1.00 |

| Sleep Quality | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.26 | .75–1.08 |

| Perceived Stress | 1.01 | 0.05 | 0.79 | .92–1.11 |

| Depression | 1.04 | 0.10 | 0.66 | .87–1.25 |

| Fatigue | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.50 | .90–1.05 |

Acknowledgments

MAA Grant Support:

2015 – 2017 National Institute of Nursing Research (1 F31 NR015179-01A1)

2014 – 2016 Heart Failure Society of America Nursing Research Grant

2014-2015 Predoctoral Clinical Research Training Program (NIH 5TL1TR001078-02)

JTB Grant Support

2016-2017 National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR012715)

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Russell has served on the Data Monitoring and Safety Board for Thoratec.

References

- 1.Rose Ea, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, Heitjan D, Stevenson LW, Dembitsky W, et al. Long term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(20):1435–1443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abshire M, Prichard R, Cajita M, DiGiacomo M, Dennison Himmelfarb C. Adaptation and coping in patients living with an LVAD: A metasynthesis. Hear Lung J Acute Crit Care. 2016;45(5):397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2016.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitko LA, Hupcey JE, Birriel B, Alonso W, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Patients’ decision making process and expectations of a left ventricular assist device pre and post implantation. Heart Lung. 2016;45(2):95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEwen BS, Stellar E. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. [Accessed July 16, 2014];Arch Intern Med. 1993 153(18):2093–2101. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8379800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Güder G, Bauersachs J, Frantz S, Weismann D, Allolio B, Ertl G, et al. Complementary and incremental mortality risk prediction by cortisol and aldosterone in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115(13):1754–1761. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(1):55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad T, Wang T, O’Brien EC, Samsky MD, Pura JA, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Effects of left ventricular assist device support on biomarkers of cardiovascular stress, fibrosis, fluid homeostasis, inflammation, and renal injury. JACC Hear Fail. 2015;3(1):30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redeker NS, Muench U, Zucker MJ, Walsleben J, Gilbert M, Freudenberger R, et al. Sleep disordered breathing, daytime symptoms, and functional performance in stable heart failure. [Accessed May 19, 2015];Sleep. 2010 33(4):551–560. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.4.551. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2849795&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casida JM, Parker J. A preliminary investigation of symptom pattern and prevalence before and up to 6 months after implantation of a left ventricular assist device. J Artif Organs. 2012;15(2):211–214. doi: 10.1007/s10047-011-0622-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abshire MA, Russell SD, Davidson PM, Budhathoki C, Han HR, Grady KL, et al. Social Support Moderates the Relationship between Perceived Stress and Quality of Life in Patients with a Left Ventricular Assist Device. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018 doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000487. in Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White-Williams C, Fazeli-Wheeler P, Myers S, Kirklin J, Pamboukian S, Naftel D, et al. HRQOL Improves from Before to 2 Years After MCS, Regardless of Implant Strategy: Analyses from INTERMACS. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2016;35(4):S25. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.01.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juster R-P, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35(1):2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellhammer DH, Wüst S, Kudielka BM. Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federenko I, Wüst S, Hellhammer DH, Dechoux R, Kumsta R, Kirschbaum C. Free cortisol awakening responses are influenced by awakening time. [Accessed January 18, 2018];Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004 29(2):174–184. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00021-0. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14604599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilcox RR, Granger DA, Szanton S, Clark F. Cortisol diurnal patterns, associations with depressive symptoms, and the impact of intervention in older adults: Results using modern robust methods aimed at dealing with low power due to violations of standard assumptions. Horm Behav. 2014;65(3):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. [Accessed November 17, 2014];Psychiatry Res. 1989 28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2748771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. Stress A Global Measure of Perceived. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammash MH, Hall La, Lennie Ta, Heo S, Chung ML, Lee KS, et al. Psychometrics of the PHQ-9 as a measure of depressive symptoms in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12(5):446–453. doi: 10.1177/1474515112468068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. [Accessed July 10, 2014];J Gen Intern Med. 2001 16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1495268&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belza BL, Henke CJ, Yelin EH, Epstein WV, Gilliss CL. Correlates of fatigue in older adults with rheumatoid arthritis. [Accessed May 19, 2015];Nurs Res. 42(2):93–99. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8455994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soto GE, Jones P, Weintraub WS, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA. Prognostic value of health status in patients with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;110(5):546–551. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136991.85540.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleg JL, Piña IL, Balady GJ, Chaitman BR, Fletcher B, Lavie C, et al. Assessment of functional capacity in clinical and research applications: An advisory from the Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. [Accessed July 16, 2014];Circulation. 2000 102(13):1591–1597. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.13.1591. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11004153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasin T, Topilsky Y, Kremers WK, Boilson Ba, Schirger Ja, Edwards BS, et al. Usefulness of the six-minute walk test after continuous axial flow left ventricular device implantation to predict survival. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(9):1322–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grady KL, Wissman Sherri, Naftel DC, Myers S, Gelijins A, Moskowitz A, et al. Age and gender differences and factors related to change in health-related quality of life from before to 6 months after left ventricular assist device implantation: Findings from Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2016;35(6):777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.01.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, Kormos RL, Stevenson LW, Blume ED, et al. Seventh INTERMACS annual report: 15,000 patients and counting. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2015;34(12):1495–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Out D, Hall RJ, Granger Da, Page GG, Woods SJ. Assessing salivary C-reactive protein: longitudinal associations with systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease risk in women exposed to intimate partner violence. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(4):543–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, Goldstein NE, Matlock DD, Arnold RM, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2012;125(15):1928–1952. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bassett SM, Lupis SB, Gianferante D, Rohleder N, Wolf JM. Sleep quality but not sleep quantity effects on cortisol responses to acute psychosocial stress. Stress. 2015;18(6):638–644. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2015.1087503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackowska M, Ronaldson A, Brown J, Steptoe A. Biological and psychological correlates of self-reported and objective sleep measures. J Psychosom Res. 2016;84:52–55. doi: 10.1016/J.JPSYCHORES.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parissis JT, Nikolaou M, Farmakis D, Paraskevaidis IA, Bistola V, Venetsanou K, et al. Self-assessment of health status is associated with inflammatory activation and predicts long-term outcomes in chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(2):163–169. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee CS, Moser DK, Lennie Ta, Tkacs NC, Margulies KB, Riegel B. Biomarkers of myocardial stress and systemic inflammation in patients who engage in heart failure self-care management. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(4):321–328. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31820344be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caruso R, Trunfio S, Milazzo F, Campolo J, De Maria R, Colombo T, et al. Early expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in left ventricular assist device recipients with multiple organ failure syndrome. ASAIO J. 2010;56(4):313–318. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3181de3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee KS, Lennie TA, Heo S, Song EK, Moser DK. Prognostic Importance of Sleep Quality in Patients with Heart Failure. Am J Crit Care. 2016;25(6):516–525. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2016219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blumenthal-Barby JS, Kostick KM, Delgado ED, Volk RJ, Kaplan HM, Wilhelms LA, et al. Assessment of patients’ and caregivers’ informational and decisional needs for left ventricular assist device placement: Implications for informed consent and shared decision-making. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34(9):1182–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heilmann C, Kuijpers N, Beyersdorf F, Berchtold-Herz M, Trummer G, Stroh AL, et al. Supportive psychotherapy for patients with heart transplantation or ventricular assist devices☆☆☆. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2011;39(4):e44–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayor E. Gender roles and traits in stress and health. Front Psychol. 2015;6:779. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yousuf Zafar S. Financial Toxicity of Cancer Care: It’s Time to Intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5):djv370. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873–898. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]