Abstract

Chinese herbal medicine has been practiced for the prevention, treatment, and cure of diseases for thousands of years. Herbal medicine involves the use of natural compounds, which have relatively complex active ingredients with varying degrees of side effects. Some of these herbal medicines are known to cause nephrotoxicity, which can be overlooked by physicians and patients due to the belief that herbal medications are innocuous. Some of the nephrotoxic components from herbs are aristolochic acids and other plant alkaloids. In addition, anthraquinones, flavonoids, and glycosides from herbs also are known to cause kidney toxicity. The kidney manifestations of nephrotoxicity associated with herbal medicine include acute kidney injury, CKD, nephrolithiasis, rhabdomyolysis, Fanconi syndrome, and urothelial carcinoma. Several factors contribute to the nephrotoxicity of herbal medicines, including the intrinsic toxicity of herbs, incorrect processing or storage, adulteration, contamination by heavy metals, incorrect dosing, and interactions between herbal medicines and medications. The exact incidence of kidney injury due to nephrotoxic herbal medicine is not known. However, clinicians should consider herbal medicine use in patients with unexplained AKI or progressive CKD. In addition, exposure to herbal medicine containing aristolochic acid may increase risk for future uroepithelial cancers, and patients require appropriate postexposure screening.

Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury, Alkaloids, Anthraquinones, Aristolochic Acids, chronic kidney disease, Drugs, Chinese Herbal, Fanconi Syndrome, Flavonoids, Glycosides, Herbal Medicine, Humans, Incidence, kidney, Metals, Heavy, Neoplasms, Nephrolithiasis, nephrotoxicity, Plants, Medicinal, Renal Insufficiency, Chronic, rhabdomyolysis, Traditional Chinese Medicine

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (1), traditional medicine is either the mainstay of medical treatment or serves as a complement to it in up to 75%–80% of the world population, mostly in the developing world (2). Traditional medicine, including traditional Chinese medicine, has been practiced for the prevention, treatment, and cure of disorders or diseases for thousands of years (3) and for many kinds of diseases (4). Importantly, Chinese herbal medicine is an important component of traditional Chinese medicine, and it has become popular all over the world as a source of alternative therapies. The available data suggest that the traditional Chinese medicine market is large and that Chinese herbs have been exported to over 175 countries and regions, including Japan, South Korea, India, Germany, Holland, other European countries, and the United States (5). The total market value of Chinese materia medica was estimated to amount to United States $83.1 billion in 2012, an increase of >20% from the previous year (1). Therefore, the effect of herbal medicine use is global and expanding. Given the potential hazardous implications of the use of non-Food and Drug Administration (non-FDA)–approved supplements, it is important to increase global awareness about herbal medicine.

Chinese herbal medicine is composed mainly of natural compounds with complex active ingredients that can lead to varying degrees of side effects (3). Some of these herbal medicines are also known to cause nephrotoxicity, which is often overlooked by physicians and patients due to the belief that herbal medications are innocuous (6). The incidence of kidney injury induced by Chinese herbal medicines is difficult to assess (7). However, in total, drug-related nephrotoxicity has been reported to contribute to about 26% of cases in patients with hospital-acquired AKI and 18% of cases in patients with community-acquired AKI globally. The critically ill patients with drug-induced AKI usually need to RRT; the contribution of Chinese herbal medicine to these figures is not clear (8). Adverse event reporting is generally voluntary, and toxicity has been documented through patients reports and series (interestingly, most of which are not from China). This paucity of data often leads to a false sense of reassurance that nephrotoxicity is a rare event when, in fact, few data exist. This article will focus on the kidney toxicity of Chinese herbal medicine. Nephrotoxicity caused by other traditional medicines, which are not used frequently in China, is beyond the scope of this review.

Chinese Herbal Medicines Associated with Nephrotoxicity

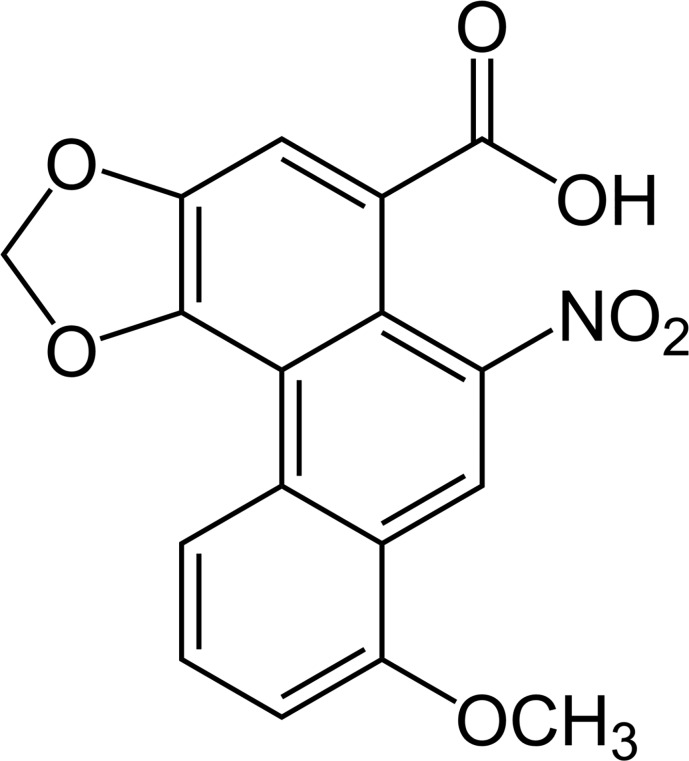

There is a substantial amount of basic research centered on the nephrotoxicity associated with Chinese herbal medicine use over the last two decades. The main nephrotoxic components from herbs are aristolochic acids (Figure 1) (structure of aristolochic acid) and alkaloid compounds (9,10). Aristolochic acids are a family of carcinogenic, mutagenic, and nephrotoxic phytochemicals, and they are mainly derived from the birthwort family of plants (Aristolochia contorta Bunge, Aristolochia manshuriensis Kom, Clematis Chinensis Osbeck, and Aristolochia cathcartii Hook). Nephrotoxic alkaloids are derived from Tripterygium regelii Sprague et Takeda, Stephania tetrandra S. Moore, Strychnos nux-vomica Linn, and Aconitum carmichaeli Debx. In addition, Chinese herbal medicine may contain anthraquinones, flavonoids, and glycosides that have nephrotoxicity. A list of Chinese herbal medicines known to contain aristolochic acid, alkaloids, and other nephrotoxic components is given in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of aristolochic acid, one of the main components of nephrotoxicity of Chinese herbs.

Table 1.

| Active Ingredients | Latin Name | English Name | Chinese Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aristolochic acid | Aristolochiaceae | Aristolochic | Ma douling |

| Aristolochic acid | Aristolochia debilis Sieb. et Zucc. | Radix aristolochiae | Qing muxiang |

| Aristolochic acid | Aristolochia obliqua S. M. Hwang | Fangchi | Guang fangji |

| Aristolochic acid | Aristolochia manshuriensis Kom | Manshuriensis | Guan mutong |

| Aristolochic acid | Aristolochia cinnabarina C. Y. Cheng et J. L. Wu | Root of Kaempfer Dutchmans pipe | Zhu shalian |

| Aristolochic acid | Aristolochia mollissima Hance | Aristolochia | Xun gufeng |

| Aristolochic acid | Clematis Chinensis Osbeck | Radix clematidis | Wei lingxian |

| Aristolochic acid | Asarum heterotropoides Fr. Schmidt var. mandshuricum (Maxim.) Kitag | Asarum sieboldii | Xixin |

| Aristolochic acid | Aristolochia cathcartii Hook | Aristolochia | Fangji |

| Tripterygine | Tripterygium regelii Sprague et Takeda | Tripterygium | Lei gongteng |

| Calycanthine | Chimonanthus praecox (Linn.) Link | Chimonanthus | La meigen |

| Tetrandrine | Stephania tetrandra S. Moore | Tetrandra | Fen fangji |

| Dauricine | Menispermum dauricum DC | Menispermi | Bei dougen |

| Brucine | Strychnos nux-vomica Linn | Strychnos | Ma qianzi |

| Strychnine | Strychnos nux-vomica Linn | Strychnos | Ma qianzi |

| Veratrine | Leucothoe griffithiana C.B. Clarke | Wood veratry | Mu lilu |

| Aconitine | Aconitum carmichaeli Debx | Aconitum | Wutou |

| Pyrrolizidine alkaloids | Senecio scandens Buch-Ham | Groundsel | Qian liguang |

| Aconitine | Aconitum tanguticum (Maxim.) Stapf | Monkshood | Fuzi |

| Croton oil | Croton caudatus Geisel. Croton | Croton | Ba dou |

| Anthraquinone compounds | Cassia obtusifolia L. | Cassia | Jue mingzi |

| Anthraquinone compounds | Cassia angustifolia Vahi | Folium senne | Fan xieye |

| Anthraquinone compounds | Rheum officinale Baill | Rhubarb | Da huang |

| Chamaejasme flavonoids | Euphorbia fischeriana Steud | Stellera chamaejasme | Lang du |

| Podophyllotoxin | Dysosma versipellis (Hance) M. Cheng ex Ying | Dysosma | Ba jiaolian |

| Alisol A 24-acetate | Alisma plantago-aquatica Linn | Alisma | Zexie |

| Brucea alcohol | Brucea mollis Wall | Brucea | Ya danzi |

| Bakuchiol | Psoralea corylifolia Linn | Psoralen | Bu guzhi |

| Geniposide | Gardenia jasminoides Ellis | Gardenia | Zhizi |

| Esculentoside A | Phytolacca acinosa Roxb | Pokeberry foot | Shanglu |

Manifestation of Nephrotoxicity Associated with Chinese Herbal Medicines

Nephrotoxicity associated with Chinese herbal medicines includes AKI, CKD, nephrolithiasis, rhabdomyolysis, Fanconi syndrome, and urothelial carcinoma. Representative patient reports of these nephrotoxic manifestations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chinese herbal medicines associated with nephrotoxicity

| Possible Toxic Compound | Latin Name | English Name/Chinese Name | Indications | Kidney Manifestations | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aristolochic acid | Aristolochia spp. | Aristolochia, Guan Mu tong, Han Fang Ji | To induce weight loss, liver disease, arthritis, headache, edema | Chronic interstitial nephritis, renal interstitial fibrosis, Fanconi syndrome, urothelial carcinoma | 19–22,43 |

| Flavonoid (sciadopitysin) | Taxus cerebica | Chinese yew | Diabetes, vascular diseases | Acute tubular necrosis, acute interstitial nephritis | 11 |

| Flavonoid | Cupressus funebris Endl | Mourning cypress | Vascular diseases, instead of “yew” | Acute tubular necrosis, acute interstitial nephritis | 14 |

| Flavonoid oligomeric procyanthins | Crataegus orientalis | Hawthorn | Congestive heart failure, hypertension, hyperlipidemia | AKI | 15 |

| Ephedrine, norephedrine, pseudoephedrine | Ephedra sinica | Ma huang | Cough, to induce weight loss, to cause sexual arousal | AKI, nephrolithiasis | 32–34,44 |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid, glycyrrhizic acid | Glycyrrhiza glabra | Licorice Gancao | Cough, sore throat, arthritis, to induce weight loss | Acute tubular necrosis, hypokalemic nephropathy, Fanconi syndrome | 28–30,45 |

| Anthraquinones, oxalic acid | Rhizoma rhei | Rhubarb | Laxative, anti-inflammatory | Interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy | 31,45 |

| Active moiety triptolide | Tripterygium wifordii | Lei Gong Teng | Arthritis, anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressant | Acute tubular necrosis | 46 |

| Oxidative degradation products | Aloe capensis | Cape aloe | Constipation, insect bites | Acute tubular necrosis, parenchymatous nephritis | 31,45 |

| Colchicine | Colchicum autumnale | Autumn crocus | Gout | AKI | 47 |

| Dioscorine, dioscine | Discorea quartiniana | Yam | Taken as food, to cause poisoning or induce suicide | Acute tubular necrosis | 48 |

| Irritant chemicals in the latex of the plant | Euphorbia matabelensis, Euphorbia paralias | Spurge | Edema, to induce abortion | Acute tubular necrosis | 12,49 |

| Andrographolide | Andrographis paniculata | Chuan-Xin-Lian (heart piercing lotus) | Infectious disease, such as upper and lower respiratory tract infection, acute enteritis, bacillary dysentery | AKI, acute tubular necrosis | 13 |

AKI

Nephrotoxicity associated with Chinese herbal medicine is mostly reported through patient reports or patient series. In many patients, the exact pathology associated with AKI is not well understood, but in others, a diagnosis has been made on the basis of kidney biopsy or other clinical observations that substantiate a clear mechanism of injury. In several patients, the most common causes of AKI were acute tubular necrosis and acute interstitial nephritis (11–14). Several representative patients are discussed.

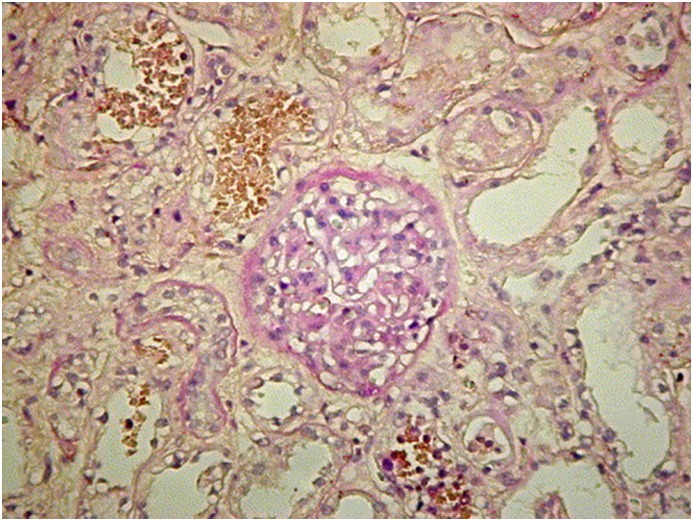

Lin and Ho (11) reported on two patients with AKI induced by sciadopitysin, a type of flavonoid extracted from Taxus cerebica, which was used for treating diabetes mellitus. In these patients, kidney biopsy showed acute interstitial nephritis with acute tubular necrosis. Lee et al. (14) reported a case where a patient developed AKI, acute hepatic failure, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia after oral intake of a hot water extract of Cupressus funebris Endl (mourning cypress), which is rich in flavonoids. Her kidney biopsy (Figure 2) showed acute tubular necrosis, interstitial nephritis, and hemoglobin casts. Again, no other etiologies for these toxicities could be found. Horoz et al. (15) reported on a patient with multisystem hypersensitivity reaction and progressive AKI associated with the consumption of Crataegus orientalis or hawthorn. In this patient, the kidney biopsy revealed acute interstitial nephritis (16). A more recent compound associated with AKI is andrographolide. Andrographolide, the primary component of a traditional medicinal herb Andrographis paniculata (chuan xin lian) is widely used in China for the treatment of upper and lower respiratory tract infection and dysentery. In 2014, Zhang et al. (13) published a systemic analysis review of the Chinese literature from January 1978 to August 2013 that included 26 patient reports of andrographolide-induced AKI. The major pathologic finding associated with AKI in these patients was acute tubular necrosis. The mechanism of andrographolide-induced AKI is not clear.

Figure 2.

Histologic picture of a case of AKI after oral intake of a hot water extract of Cupressus funebris. The figure shows glomeruli are essentially normal. Kidney tubules show thickened tubular basement membrane, and many epithelial cells are missing, necrotic, or flattened. Hemoglobin casts, interstitial fibrosis, and cellular infiltrate also are identified (periodic acid–Schiff stain). Original magnification, ×200.

Chinese Herbal Medicine and CKD

The compound that has most tightly linked chronic kidney injury and Chinese herbal medicine is aristolochic acid. Recognizing the link, the condition has been termed Chinese herbal nephropathy. Vanherweghem and colleagues (17) first described progressive chronic interstitial fibrosis and advanced kidney failure in nine young Belgian women who were using Chinese herbal slimming remedies. Kidney biopsies done in eight of these women revealed extensive interstitial fibrosis with minimal glomerular changes. More patients with similar findings soon came to light, and aristolochic acid was identified as the likely causative agent (10,17,18). Since then, patients with aristolochic acid nephropathy have been reported worldwide, most of whom are from Asia (19–22). A retrospective study of 86 patients with aristolochic acid nephropathy reported that 87% (67 patients) present with CKD and that 22% (19 patients) presented with AKI (23).

Excessive intake of aristolochic acid is a major cause of aristolochic acid nephropathy and Balkan nephropathy, which is a chronic tubulointerstitial disease associated with a high frequency of urothelia atypia, occasionally culminating in tumors of the kidney pelvis and urethra. In contrast to the classic presentation of aristolochic acid nephropathy, which is characterized by a rapid decline in kidney function (6 months to 2 years), Balkan nephropathy is slowly progressive (10–20 years), likely due to low-level exposure (18). In addition to AKI and CKD, the clinical manifestations of aristolochic acid nephropathy also include proximal tubular dysfunction (glycosuria and increased excretion of low molecular weight proteins), hypertension, severe anemia, metabolic acidosis, small kidneys on kidney ultrasound, and a high risk of urothelial malignancies, with estimated rates of 40%–46% (17,21,22). The cumulative dose of aristolochia, being a women, and a genetically determined predisposition toward carcinogenesis put patients at higher risk for urothelia malignancies (18,24).

In vivo and in vitro experiments have elucidated the operative mechanism of aristolochic acid nephropathy: (1) endoplasmic reticulum stress and injury (9,25), (2) oxidative stress injury (26), (3) immune-mediated inflammatory mechanism (27), and (4) kidney tubular epithelial cell transdifferentiation (20). Thus far, there are no effective therapies, but patients with aristolochic acid nephropathy require periodic screening for uroepithelial malignancies.

Other links between Chinese herbal medicine and CKD include (1) chronic hypokalemic nephropathy associated with the cough suppressant Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice) (28–30) and (2) chronic interstitial nephritis and tubular atrophy associated with prolonged use of a Chinese herbal slimming pill containing anthraquinone derivatives extracted from rhubarb (Rhizoma rhei) (31).

Nephrolithiasis

Chinese herbal medicine–induced nephrolithiasis is not known to be very common. There are two published patient reports of kidney stones associated with Ephedra sinica (ephedra/ma huang), which is a very popular herb in treatment of respiratory conditions (4). Both patients were young adult men with a history of ingesting 40–3000 mg/d ephedra over several months (32,33). The components of the kidney stones in these patients were ephedrine, norephedrine, and pseudoephedrine. Because of these events and other adverse events associated with ephedra, in April 2004, the FDA prohibited the sale of ephedra-containing dietary supplements in the United States (30).

Rhabdomyolysis

There are several associations between rhabdomyolysis and Chinese herbal medicine use. G. glabra (licorice)–induced AKI secondary to rhabdomyolysis has been reported. In one case (28), a 78-year-old man who consumed 280 mg/d of licorice for 7 years was hospitalized for muscle pain and AKI. The initial laboratory results revealed pronounced hypokalemia with elevated creatine phosphokinase and myoglobin levels. In another case (29), a 29-year-old woman who consumed 30 licorice tablets per day for 4 months to lose weight developed muscle pain and was found to have AKI with hypokalemia and an elevated creatine phosphokinase. A kidney biopsy in this patient revealed severely damaged tubular cells with intense vacuolar formations. The other compound associated with rhabdomyolysis is E. sinica (ephedra/ma huang). In one representative case (34), a healthy 21-year-old US Army soldier developed extreme elevations of creatine phosphokinase as well as AKI after regularly ingesting two tablets of an herbal supplement containing ephedra every day for a month to improve his physical fitness test.

Factors Influencing Nephrotoxicity Associated with Chinese Herbal Medicine

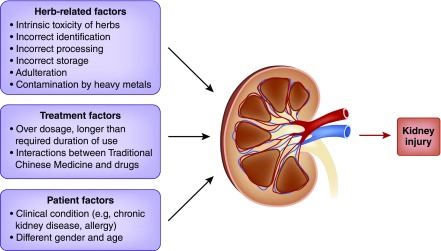

An interesting observation is that not all people using Chinese herbal medicine develop AKI or CKD, and there are several factors that may contribute to the ultimate nephrotoxicity of these compounds (Figure 3) (factors influencing the development of kidney disease associated with Chinese herbal medicine).

Figure 3.

Factors influencing the development of kidney disease associated with herbal medicine. The figure shows herb-related, treatment, and patient factors which may contribute to nephrotoxicity of hebal medicine.

Intrinsic Toxicity of Herbs and Incorrect Identification of Potentially Toxic Compounds

There are misconceptions and mislabeling regarding particular Chinese herbal medicines that have led to serious health consequences. These errors can lead to important exposures with a high risk of toxicity. For instance, the root of Asarum (xi xin) has a low level of aristolochic acid and has been commonly used in traditional Chinese medicine formulations as an analgesic to treat headache, toothache, and other inflammatory diseases. However, the whole Asarum plant has a high level of aristolochic acid and can be mistakenly used in manufacturing to yield an herbal product with high risk of nephrotoxicity (35). In another example, >100 women in Belgium and France were reported to have suffered extensive interstitial fibrosis of the kidneys after ingesting a weight loss regimen involving Chinese herbal medicine from 1990 to 1992. The investigation into these patients found that one of the herbs in the pills, Stephania tetrandra (fen fang ji or han fang ji), was inadvertently replaced during manufacturing by Aristolochia fangchi (guang fang ji), which contains very high levels of aristolochic acid (36,37). Caulis aristolochiae manshuriensis (guan mu tong), which also contains aristolochic acid, inadvertently replaced Lardizabalaceae (mu tong) in a traditional Chinese medicine formula and also caused nephrotoxicity in patients (38). These types of errors are generally not committed by experienced herbalists and when modern analytical technologies for confirmation of safety are used (39).

Incorrect Processing or Storage and Adulteration

The majority of Chinese herbal medicine compounds must undergo physical and/or chemical pretreatment processes that are critical for preservation, detoxification, or enhancing efficacy (3,39). These processes include sun drying, roasting, wine frying, vinegar frying, steaming, fumigation, and other processing techniques that may not be known. Incorrect processing techniques may contribute to nephrotoxicity. For example, Carthamus tinctorius has recently been found to be contaminated with Auramine O dye, which was used to help retain its color so that it could yield a higher retail price. However, Auramine O is a “nonedible” substance, and it is known to be a carcinogenic industrial dye that can cause kidney and liver toxicity (39).

Unexpected nephrotoxicity induced by some Chinese herbal medicines may be associated with poor storage conditions, which may cause alteration of the chemical composition of the compounds (6). For instance, oxidative degradation products related to Aloe species were found in a type of Chinese herbal medicine stored in ambient heat in a plastic bottle. This inadequately stored herbal medicine induced AKI because of severe vomiting and dehydration (6).

Contamination by Heavy Metals

Chinese herbal medicines may also absorb unknown environmental contaminants, such as heavy metals like arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury, which may be hazardous (6,39). For example, mice exposed to the traditional Chinese medicine niu huang jie du pian, which contains realgar (As4S4), developed severe hepatic and kidney injury (40). In addition, arsenic and mercury were found to exceed the normal limits in some Panax notoginseng (san qi) samples (39,41). The exact role of heavy metal contamination in nephrotoxicity and how common this may be are unknown.

Prevention and Treatment

The first principle of effective therapy is prevention of toxicity, which relies on the following critical issues (Table 3): (1) safe manufacturing processes that ensure high standards that avoid contamination with dangerous substances as well as clear labeling as to what compounds (and how much) are present in the herbal medicine, (2) licensing of practitioners to ensure knowledge of traditional Chinese medicines and their potential side effects, (3) limitations on the dose and length of therapies as well as appropriate monitoring for adverse effects, and (4) development of a clear understanding regarding the potential interactions between herbal medicines and other medications (42). For instance, there were two patient reports describing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced nephrotoxicity that was exacerbated by concomitant exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and herbal medicines (31). These interactions have not been well cataloged and present a clear danger to patients who may be taking multiple “Western” and traditional Chinese medications.

Table 3.

Methods to prevent nephrotoxicity associated with herbal medicine

| N | Main Principles |

|---|---|

| 1 | Increased attention should be given to the possible nephrotoxicity associated with herbal medicine, the appropriate preparation, the comedication that has already been prescribed to the patient |

| 2 | Preclinical pharmacologic and toxicologic assessment of herbal medicine is recommended before widespread use |

| 3 | Extreme caution should be observed when using herbal medicine associated with nephrotoxicity |

| 4 | Avoid herbal medicine overdosage and long-term use |

| 5 | Carefully record all cases of adverse reactions (e.g., kidney function, allergy) |

| 6 | Develop a much stronger and more stringent system to manage toxicity in herbal medicine |

When nephrotoxicity is encountered, treatment follows general principles for patients with AKI, including supportive care, avoidance of further nephrotoxin exposure, and attention to fluid and electrolyte balance. Given the risks of CKD in these patients, longitudinal follow-up is needed to monitor kidney function. In those patients who may have been exposed to aristolochic acid, periodic screening for uroepithelial cancer must be undertaken.

Conclusion

Herbal medicines have played and continue to play an important role in China and throughout the world (1). A common fallacy is that the majority of people who use these medications consider them to be “natural, green, and nontoxic.” However, numerous reports of toxicity should bring caution that these compounds may lead to serious adverse effects. Systematic toxicologic studies on herbal medicines and the same professional surveillance and strict quality control standards that are regularly used for conventional medicines are essential.

To summarize, the exact incidence of kidney injury due to nephrotoxic herbal medicine is not known. It is an under-recognized and under-reported cause of nephrotoxicity. Undocumented traditional Chinese medicine ingestion should always be considered when investigating a patient with unexplained kidney disease. Nephrotoxicity of Chinese herbal medicine is an example of how such practice is also common in other parts of the world. Nephrologists should always be encouraged to obtain a detailed history of supplements other than prescribed medications, including (but not limited to) Chinese herbal medicine, regardless of the patients’ ethnic background. Increased global awareness is important, because recognition and managing this entity will help build the body of evidence to develop effective therapies.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 81774065 and 81303092.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.WHO: WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023, December 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm_strategy14_23/en/. Accessed March 15, 2017

- 2.Bardia A, Nisly NL, Zimmerman MB, Gryzlak BM, Wallace RB: Use of herbs among adults based on evidence-based indications: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey. Mayo Clin Proc 82: 561–566, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan T, Briggs J, Liu L, Lu A, Greef JVD, Xu A: The art and science of traditional medicine. Part 2: Multidisciplinary approaches for studying traditional medicine. Science 347: S27–S51, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Q, Zhu L, Lerberghe WV: The importance of traditional Chinese medicine services in health care provision in China. Univ Forum 2: 1–8, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teng L, Zu Q, Li G, Yu T, Job KM, Yang X, Di L, Sherwin CM, Enioutina EY: Herbal medicines: Challenges in the modern world. Part 3: China and Japan. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 9: 1225–1233, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luyckx VA: Nephrotoxicity of alternative medicine practice. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 19: 129–141, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu X, Nie S, Liu Z, Chen C, Xu G, Zha Y, Qian J, Liu B, Han S, Xu A, Xu X, Hou FF: Epidemiology and clinical correlates of AKI in Chinese hospitalized adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1510–1518, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Cui Z, Fan M: Hospital-acquired and community-acquired acute renal failure in hospitalized Chinese: A ten-year review. Ren Fail 29: 163–168, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu XL, Yang LJ, Jiang JG: Renal toxic ingredients and their toxicology from traditional Chinese medicine. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 12: 149–159, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lv W, Piao JH, Jiang JG: Typical toxic components in traditional Chinese medicine. Expert Opin Drug Saf 11: 985–1002, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin JL, Ho YS: Flavonoid-induced acute nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 23: 433–440, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boubaker K, Ounissi M, Brahmi N, Goucha R, Hedri H, Abdellah TB, El Younsi F, Maiz HB, Kheder A: Acute renal failure by ingestion of Euphorbia paralias. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 24: 571–575, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang WX, Zhang ZM, Zhang ZQ, Wang Y, Zhou W: Andrographolide induced acute kidney injury: Analysis of 26 cases reported in Chinese Literature. Nephrology (Carlton) 19: 21–26, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JJ, Chen HC: Flavonoid-induced acute nephropathy by Cupressus funebris Endl (Mourning Cypress). Am J Kidney Dis 48: e81–e85, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horoz M, Gok E, Genctoy G, Ozcan T, Olmaz R, Akca M, Kiykim A, Gurses I: Crataegus orientalis associated multiorgan hypersensitivity reaction and acute renal failure. Intern Med 47: 2039–2042, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crataegus oxyacantha (Hawthorn). Monograph. Altern Med Rev 15: 164–167, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debelle FD, Vanherweghem JL, Nortier JL: Aristolochic acid nephropathy: A worldwide problem. Kidney Int 74: 158–169, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jadot I, Declèves AE, Nortier J, Caron N: An integrated view of aristolochic acid nephropathy: Update of the literature. Int J Mol Sci 18: E297, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong YT, Fu LS, Chung LH, Hung SC, Huang YT, Chi CS: Fanconi’s syndrome, interstitial fibrosis and renal failure by aristolochic acid in Chinese herbs. Pediatr Nephrol 21: 577–579, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang L, Li X, Wang H: Possible mechanisms explaining the tendency towards interstitial fibrosis in aristolochic acid-induced acute tubular necrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 445–456, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L, Su T, Li XM, Wang X, Cai SQ, Meng LQ, Zou WZ, Wang HY: Aristolochic acid nephropathy: Variation in presentation and prognosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 292–298, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poon WT, Lai CK, Chan AYW: Aristolochic acid nephropathy: The Hong Kong perspective. Hong Kong J Nephrol 9: 7–14, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen D, Tang Z, Luo C, Chen H, Liu Z: Clinical and pathological spectrums of aristolochic acid nephropathy. Clin Nephrol 78: 54–60, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nortier J, Pozdzik A, Roumeguere T, Vanherweghem JL: [Aristolochic acid nephropathy (“Chinese herb nephropathy”)]. Nephrol Ther 11: 574–588, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katsoulieris E, Mabley JG, Samai M, Sharpe MA, Green IC, Chatterjee PK: Lipotoxicity in renal proximal tubular cells: Relationship between endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress pathways. Free Radic Biol Med 48: 1654–1662, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Declèves AÉ, Jadot I, Colombaro V, Martin B, Voisin V, Nortier J, Caron N: Protective effect of nitric oxide in aristolochic acid-induced toxic acute kidney injury: An old friend with new assets. Exp Physiol 101: 193–206, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pozdzik AA, Salmon IJ, Husson CP, Decaestecker C, Rogier E, Bourgeade MF, Deschodt-Lanckman MM, Vanherweghem JL, Nortier JL: Patterns of interstitial inflammation during the evolution of renal injury in experimental aristolochic acid nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 2480–2491, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito T, Tsuboi Y, Fujisawa G, Sakuma N, Honda K, Okada K, Saito K, Ishikawa S, Saito T: An autopsy case of licorice-induced hypokalemic rhabdomyolysis associated with acute renal failure: Special reference to profound calcium deposition in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi 36: 1308–1314, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishikawa S, Kato M, Tokuda T, Momoi H, Sekijima Y, Higuchi M, Yanagisawa N: Licorice-induced hypokalemic myopathy and hypokalemic renal tubular damage in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 26: 111–114, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabardi S, Munz K, Ulbricht C: A review of dietary supplement-induced renal dysfunction. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 757–765, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwan TH, Tong MK, Leung KT, Lai CK, Poon WT, Chan YW, Lo WH, Au TC: Acute renal failure associated with prolonged intake of slimming pills containing anthraquinones. Hong Kong Med J 12: 394–397, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blau JJ: Ephedrine nephrolithiasis associated with chronic ephedrine abuse. J Urol 160: 825, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell T, Hsu FF, Turk J, Hruska K: Ma-huang strikes again: Ephedrine nephrolithiasis. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 153–159, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stahl CE, Borlongan CV, Szerlip M, Szerlip H: No pain, no gain--exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis associated with the performance enhancer herbal supplement ephedra. Med Sci Monit 12: CS81–CS84, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drew AK, Whyte IM, Bensoussan A, Dawson AH, Zhu X, Myers SP: Chinese herbal medicine toxicology database: Monograph on Herba Asari, “xi xin”. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 40: 169–172, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nortier JL, Martinez MC, Schmeiser HH, Arlt VM, Bieler CA, Petein M, Depierreux MF, De Pauw L, Abramowicz D, Vereerstraeten P, Vanherweghem JL: Urothelial carcinoma associated with the use of a Chinese herb (Aristolochia fangchi). N Engl J Med 342: 1686–1692, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw D: Toxicological risks of Chinese herbs. Planta Med 76: 2012–2018, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue X, Xiao Y, Gong L, Guan S, Liu Y, Lu H, Qi X, Zhang Y, Li Y, Wu X, Ren J: Comparative 28-day repeated oral toxicity of Longdan Xieganwan, Akebia trifoliate (Thunb.) koidz., Akebia quinata (Thunb.) Decne. and Caulis aristolochiae manshuriensis in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 119: 87–93, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu SH, Chuang WC, Lam W, Jiang Z, Cheng YC: Safety surveillance of traditional Chinese medicine: Current and future. Drug Saf 38: 117–128, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao JW, Liang SX, Wu Q, Liu J, Sun AS: Toxicology evaluation of realgar-containing niu-huang-jie-du pian as compared to arsenicals in cell cultures and in mice. ISRN Toxicol 2011: 250387, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang T, Guo R, Zhou G, Zhou X, Kou Z, Sui F, Li C, Tang L, Wang Z: Traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen: A review. J Ethnopharmacol 188: 234–258, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Smet PA: Herbal remedies. N Engl J Med 347: 2046–2056, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vanherweghem LJ: Misuse of herbal remedies: The case of an outbreak of terminal renal failure in Belgium (Chinese herbs nephropathy). J Altern Complement Med 4: 9–13, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Isnard Bagnis C, Deray G, Baumelou A, Le Quintrec M, Vanherweghem JL: Herbs and the kidney. Am J Kidney Dis 44: 1–11, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myhre MJ: Herbal remedies, nephropathies, and renal disease. Nephrol Nurs J 27: 473–478, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chou WC, Wu CC, Yang PC, Lee YT: Hypovolemic shock and mortality after ingestion of Tripterygium wilfordii hook F.: A case report. Int J Cardiol 49: 173–177, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brvar M, Ploj T, Kozelj G, Mozina M, Noc M, Bunc M: Case report: Fatal poisoning with Colchicum autumnale. Crit Care 8: R56–R59, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segasothy M, Swaminathan M, Kong NC, Bennett WM: Djenkol bean poisoning (djenkolism): An unusual cause of acute renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 25: 63–66, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dukes DC, Dukes HM, Gordon JA, Mynors JM, Weinberg RW, Davidson LA: Acute renal failure in Central Africa. The toxic effects of traditional African medicine. Cent Afr J Med 15: 71–78, 1969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]