Abstract

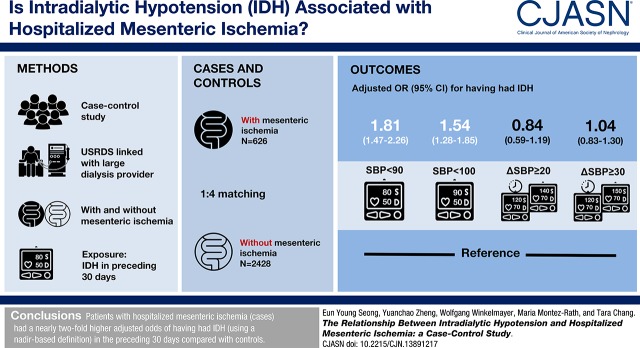

Background and objectives

Mesenteric ischemia is a rare but devastating condition caused by insufficient blood supply to meet the demands of intestinal metabolism. In patients with ESKD, it can be difficult to diagnose and has a >70% mortality rate. Patients on hemodialysis have a high prevalence of predisposing conditions for mesenteric ischemia, but the contribution of intradialytic hypotension, a potential modifiable risk factor, has not been well described.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We used data from the US Renal Data System to identify 626 patients on hemodialysis with a hospitalized mesenteric ischemia event (cases). We selected 2428 controls in up to a 1:4 ratio matched by age, sex, black race, incident dialysis year, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and peripheral artery disease. We used six different definitions of intradialytic hypotension on the basis of prior studies, and categorized patients as having had intradialytic hypotension if ≥30% of hemodialysis sessions in the 30 days before the event met the specified definition.

Results

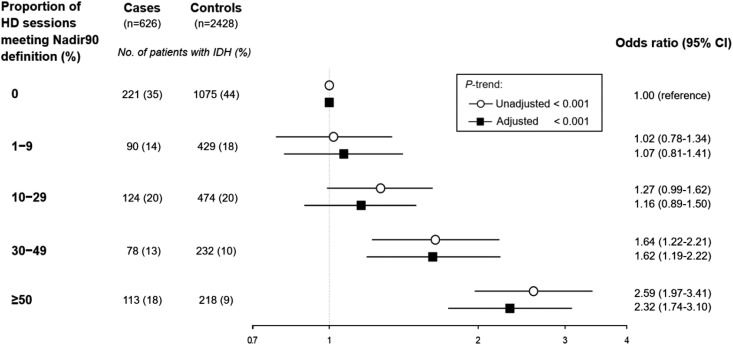

The proportion of patients with intradialytic hypotension varied depending on its definition: from 19% to 92% of cases and 11% to 94% of controls. Cases had a higher adjusted odds (1.82; 95% confidence interval, 1.47 to 2.26) of having had intradialytic hypotension in the preceding 30 days than controls when using nadir-based intradialytic hypotension definitions such as nadir systolic BP <90 mm Hg. To examine a potential dose-response association of intradialytic hypotension with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia, we categorized patients by the proportion of hemodialysis sessions having intradialytic hypotension, defined using the Nadir90 definition (0%, 1%–9%, 10%–29%, 30%–49%, and ≥50%), and found a direct association of proportion of intradialytic hypotension with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (P-trend<0.001).

Conclusions

Patients with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia had significantly higher odds of having had intradialytic hypotension in the preceding 30 days than controls, as defined by nadir-based definitions.

Keywords: hemodialysis; vascular disease; end stage kidney disease; renal dialysis; coronary artery disease; blood pressure; Peripheral Arterial Disease; risk factors; Case-Control Studies; Mesenteric Ischemia; Prevalence; Kidney Failure, Chronic; hypotension; diabetes mellitus

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Mesenteric ischemia is a rare but devastating condition caused by insufficient blood supply to meet the demands of intestinal metabolism (1), and can lead to intestinal infarction, sepsis, and death (2). In the general population, mesenteric ischemia occurs at an incidence of 0.9–2 events per 1000 person year (3), and is usually due to vascular occlusion (1). In contrast, the incidence of mesenteric ischemia in patients with ESKD on dialysis is considerably higher, with estimates of 3–19 events per 1000 person year (3,4).

Identifying mesenteric ischemia can often be difficult in patients with ESKD, where symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting may reflexively be attributed to uremia rather than to mesenteric ischemia. Delay in properly identifying mesenteric ischemia may partially account for the fact that the mortality rates associated with a mesenteric ischemia event in patients with ESKD can exceed 70% (2,5). Awareness and prompt recognition of risk factors for mesenteric ischemia is therefore important in patients with ESKD.

Embolic or thrombotic occlusion can lead to mesenteric ischemia, but patients on hemodialysis are more likely to experience nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia from relative hypoperfusion to the splanchnic circulation (1,2,6–8). Patients with ESKD have a high prevalence of predisposing conditions for systemic hypoperfusion, such as heart failure, arrhythmias, generalized atherosclerosis, and the occurrence of intradialytic hypotension (IDH) (3,8). Previous studies have estimated that IDH can occur in up to 20% of dialysis sessions (9). In turn, IDH is associated with numerous adverse outcomes including inadequate dialysis, thrombosis of vascular access, cardiovascular events, and death (10–16). Previous case reports (6,17) and single-center studies (3,8,18,19) have suggested an association between IDH and mesenteric ischemia. However, a comprehensive evaluation in patients on hemodialysis in the United States has yet to be conducted.

We used detailed clinical data from a large dialysis organization in the United States linked with data from the national ESKD registry to assess the association between IDH and mesenteric ischemia. Using a case-control study design, we hypothesized that patients with a hospitalized mesenteric ischemia event (cases) would be more likely to have had IDH in the preceding 30 days than matched patients without mesenteric ischemia (controls).

Materials and Methods

Source Population

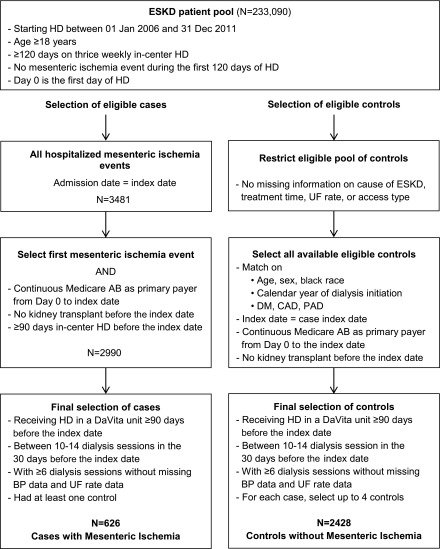

We conducted a case-control study using data from the US Renal Data System (USRDS), a national registry for patients with ESKD, merged with data from the electronic health records of a large dialysis organization ranging from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2011. We included all adult patients (≥18 years old), who were started on thrice weekly in-center hemodialysis at a participating facility and remained on this modality for at least 120 days. We identified the first day of dialysis as day 0. Patients with a hospitalized mesenteric ischemia event during the first 120 days of dialysis were excluded. The remaining cohort served as the source population from which we selected cases and controls (Figure 1). A total of three out of 643 potential cases and 238 out of 59,316 potential controls had missing information on cause of ESKD, treatment time, ultrafiltration rate, or access type. Therefore, all patients with missing information where removed from the source population (complete case analysis).

Figure 1.

Selection of patients on hemodialysis with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (cases) and without hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (controls). We identified 626 cases and matched them in up to 1:4 ratio with 2428 controls matched for age, sex, race, calendar year of dialysis initiation, DM, CAD, and PAD. HD, hemodialysis; UF, ultrafiltration.

Outcome: Hospitalized Mesenteric Ischemia

We identified hospitalized mesenteric ischemia using the following algorithm: any hospitalization with one of the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) diagnosis codes in any position: 557.0 (acute vascular insufficiency of intestine), 557.1 (chronic vascular insufficiency of intestine), or 557.9 (unspecified vascular insufficiency of intestine) (2,20,21). We additionally required an abdominal imaging procedure during the same hospitalization (Current Procedural Terminology codes 74150, 74160, 74170, 74175–74178, 74181–74183, 74185, 74261, or 74262) (2,21). We conducted a sensitivity analysis where we defined cases on the basis of hospitalization with a diagnosis code for acute mesenteric ischemia only (ICD-9 code 557.0), and an abdominal imaging procedure as in the primary analysis.

Cases

From the source population, we identified all patients with an episode of hospitalized mesenteric ischemia, with the admission date serving as the index date. We excluded patients without continuous Medicare A&B coverage as primary payer from day 0 to the index date, and patients receiving a kidney transplant at any time before the index date (Supplemental Figure 1).

Controls

We required that eligible controls match by age (±1 year), sex, black race, calendar year of dialysis initiation and dialysis vintage, diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary artery disease (CAD), and peripheral artery disease (PAD) to cases using risk-set sampling strategy (Supplemental Figure 1). We removed 14 cases with no potential controls; each of the remaining 626 cases was randomly matched with up to four controls (38 cases had fewer than four controls). As with the cases, we required that controls have continuous Medicare A&B coverage as primary payer from day 0 to the index date, and no kidney transplant at any time before the index date.

For all cases and eligible controls, we required that patients receive in-center hemodialysis at a DaVita facility for at least 90 days before the index date. Patients with <10 or >14 dialysis sessions in the 30 days before the index date were excluded, to ensure that the patient was on stable thrice weekly in-center hemodialysis for at least 30 days before the index date. Finally, we excluded any patients with fewer than six dialysis sessions with intradialytic BP information available.

Exposure: IDH

The available data included seated pre- and postdialysis systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP), and nadir intradialytic SBP and DBP. We used six different definitions of IDH (Table 1) (15). We analyzed IDH as the proportion of patients with ≥30% of sessions with IDH in the 30 days before the index date (Supplemental Figure 1) (14,15). To examine a potential dose-response association of IDH with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia, we categorized patients by the proportion of hemodialysis sessions having IDH in the 30 days before the index date, defined using the Nadir90 definition: 0%, 1%–9%, 10%–29%, 30%–49%, and ≥50%.

Table 1.

Six definitions of intradialytic hypotension (IDH) (15)

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Nadir90 | Nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg |

| Nadir100 | Nadir intradialytic SBP <100 mm Hg |

| Fall20 | (Predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥20 mm Hg |

| Fall30 | (Predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥30 mm Hg |

| Nadir90Fall20 | Nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg and (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) |

| ≥20 mm Hg | |

| Nadir90Fall30 | Nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg and (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) |

| ≥30 mm Hg |

IDH, intradialytic hypotension; Nadir90, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg; SBP, systolic BP; Nadir100, nadir intradialytic SBP <100 mm Hg; Fall20, (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥20 mm Hg; Fall30, (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥30 mm Hg; Nadir90Fall20, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg and (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥20 mm Hg; Nadir90Fall30, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg and (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥30 mm Hg.

Covariates

We ascertained information on age, sex, race (white, black, Asian, native American, and other), presumed cause of ESKD (DM, hypertension, GN, and other), and year of dialysis initiation from the USRDS patient and treatment history files. We identified preexisting comorbid conditions using ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes in any position, requiring at least one inpatient or two outpatient encounters separated by at least 1 day from day 0 to 30 days before the index date (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1) (22). We used all inpatient and outpatient physician billing claims included in the USRDS institutional claims detail and physician supplier datasets. As a sensitivity analysis, we restricted the cohort to cases of hospitalized mesenteric ischemia that occurred more than 210 days after initiation hemodialysis (day 0). We then applied a uniform lookback window of 180 days to ascertain comorbid conditions. We matched these 546 cases to up to four controls, analogous to the primary analysis.

We ascertained the number of non-nephrology outpatient visits, hospitalized days, nursing home stays, and dialysis session information (treatment time, ultrafiltration volume, and vascular access type) in the 30 days before the index date.

Antihypertensive Medications

We conducted a sensitivity analysis where we restricted the cases to patients with continuous Medicare Part D coverage in the 90 days before the index date to ascertain information on antihypertensive medications. Cases (n=427) were randomly matched with up to four controls (n=1621), as in the main analysis. We included the number of classes of antihypertensive agents (categorized as none, one to three, and four or more) in adjusted models.

Statistical Methods

For cases and controls, we summarized baseline characteristics and dialysis session information using means (SD), medians (interquartile range), or counts and proportions, as appropriate. We conducted separate analyses for each IDH definition, using unadjusted and adjusted conditional logistic regression to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of having had IDH between cases and controls. The adjusted models included cause of ESKD, number of non-nephrology outpatient visits, hospital days, any nursing home stay, on the kidney transplant waiting list, and the comorbidities listed in Table 2, plus the mean ultrafiltration rate and any central venous hemodialysis catheter use in the 30 days before the index date. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). This study was approved by an Institutional Review Board of Stanford University School of Medicine (IRB protocol 17904).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients on hemodialysis with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (cases) and without hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (controls)

| Characteristic | Cases (n=626) with Mesenteric Ischemia | Controls (n=2428) without Mesenteric Ischemia |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, yr (±SD) | 72 (10) | 72 (9) |

| Male | 267 (43%) | 1040 (43%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 463 (74%) | 1826 (75%) |

| Black | 133 (21%) | 492 (20%) |

| Asian | 17 (3%) | 83 (3%) |

| Native American | 11 (2%) | 25 (1%) |

| Other/unknown | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.1%) |

| Dialysis vintage, median (IQR), yr | 1.5 (0.8–2.6) | 1.5 (0.8–2.6) |

| Year of dialysis initiation | ||

| 2006 | 183 (29%) | 703 (29%) |

| 2007 | 140 (22%) | 546 (23%) |

| 2008 | 126 (20%) | 489 (20%) |

| 2009 | 102 (16%) | 400 (17%) |

| 2010 | 61 (10%) | 238 (10%) |

| 2011 | 14 (2%) | 52 (2%) |

| Cause of ESKD | ||

| Diabetes | 293 (47%) | 1263 (52%) |

| Hypertension | 220 (35%) | 775 (32%) |

| GN | 38 (6%) | 104 (4%) |

| Other | 54 (9%) | 208 (9%) |

| Unknown | 21 (3%) | 78 (3%) |

| Health care use in 30 d before index date | ||

| Number of non-nephrology outpatient visits (±SD) | 5.6 (4.7) | 4.8 (4.5) |

| Hospital days (±SD) | 1.0 (2.2) | 0.5 (1.6) |

| Any nursing home stay | 93 (15%) | 285 (12%) |

| On kidney transplant waiting list | 29 (5%) | 124 (5%) |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 455 (73%) | 1782 (73%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 123 (20%) | 397 (16%) |

| Angina | 146 (23%) | 493 (20%) |

| Heart failure | 456 (73%) | 1711 (71%) |

| Hypertension | 610 (97%) | 2352 (97%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 253 (40%) | 747 (31%) |

| Other arrhythmia | 211 (34%) | 645 (27%) |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 150 (24%) | 544 (22%) |

| Valvular disease | 214 (34%) | 754 (31%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 173 (28%) | 583 (24%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease/lower limb amputation | 354 (57%) | 1370 (56%) |

| Other medical comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 457 (73%) | 1798 (74%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 398 (64%) | 1559 (64%) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 157 (25%) | 488 (20%) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 44 (7%) | 96 (4%) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 14 (2%) | 45 (2%) |

| Liver disease | 67 (11%) | 213 (9%) |

| Chronic lung disease | 326 (52%) | 1013 (42%) |

| Smoking history | 63 (10%) | 176 (7%) |

| Alcohol abuse | 11 (2%) | 29 (1%) |

| Drug abuse | 29 (5%) | 65 (3%) |

| Dementia | 72 (12%) | 258 (11%) |

| Depression | 153 (24%) | 513 (21%) |

| Cancer | 91 (15%) | 320 (13%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 157 (25%) | 526 (22%) |

| Obesity | 97 (16%) | 324 (13%) |

Values are presented as mean (±SD), n (%), or median (interquartile range [IQR]), unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Cases and Controls

We identified 626 cases (i.e., patients on hemodialysis with a hospitalized mesenteric ischemia event) and matched them in up to 1:4 ratio with 2428 controls (i.e., patients on hemodialysis without a hospitalized mesenteric ischemia event matched for age, sex, race, dialysis vintage and calendar year of dialysis initiation, DM, CAD, and PAD; Figure 1, Supplemental Figure 1). The median dialysis vintage was 1.5 years (interquartile range, 0.8–2.6). Most patients were of white race, and there was a high prevalence of DM, CAD, and PAD (Table 2). In the 30 days before the index date, the number of hemodialysis sessions averaged 12±1 for cases and 13±1 for controls; cases and controls had similar mean treatment times and ultrafiltration rates (Table 3). Cases tended to have lower predialysis, postdialysis, and nadir intradialytic BP than controls, and more often used a central venous catheter for dialysis access.

Table 3.

Hemodialysis session information from the 30 d before the index date for patients with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (cases) and without hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (controls)

| Session Information | Cases (n=626) with Mesenteric Ischemia | Controls (n=2428) without Mesenteric Ischemia |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of dialysis sessions (±SD) | 12.3 (1.1) | 12.8 (1.0) |

| Treatment time (min, ±SD) | 209 (27) | 208 (26) |

| Ultrafiltration volume (L, ±SD) | −2.4 (1.3) | −2.4 (1.1) |

| Ultrafiltration rate (ml/h per kg) | 8.8 (3.6) | 8.7 (3.4) |

| SBP | ||

| Predialysis SBP (mm Hg, ±SD) | 142 (22) | 146 (20) |

| Postdialysis SBP (mm Hg, ±SD) | 135 (21) | 137 (19) |

| Nadir SBP (mm Hg, ±SD) | 107 (18) | 111 (17) |

| Change in SBP (predialysis – nadir SBP, mm Hg, ±SD) | 35 (16) | 36 (16) |

| DBP | ||

| Predialysis DBP (mm Hg, ±SD) | 69 (12) | 71 (11) |

| Postdialysis DBP (mm Hg, ±SD) | 66 (10) | 68 (10) |

| Nadir DBP (mm Hg, ±SD) | 56 (10) | 59 (10) |

| Change in DBP (predialysis – nadir DBP, mm Hg, ±SD) | 13 (8) | 12 (8) |

| Vascular access type | ||

| ≥1 sessions with AVF | 332 (53%) | 1347 (56%) |

| Number of sessions with AVF (±SD) | 6.3 (6.2) | 7.0 (6.4) |

| ≥1 sessions with AVG | 117 (19%) | 500 (21%) |

| Number of sessions with AVG (±SD) | 2.1 (4.6) | 2.5 (5.1) |

| ≥1 sessions with CVC | 210 (34%) | 676 (28%) |

| Number of sessions with CVC (±SD) | 3.8 (5.6) | 3.3 (5.5) |

Values are presented as mean (±SD) or n (%). SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft; CVC, central venous catheter.

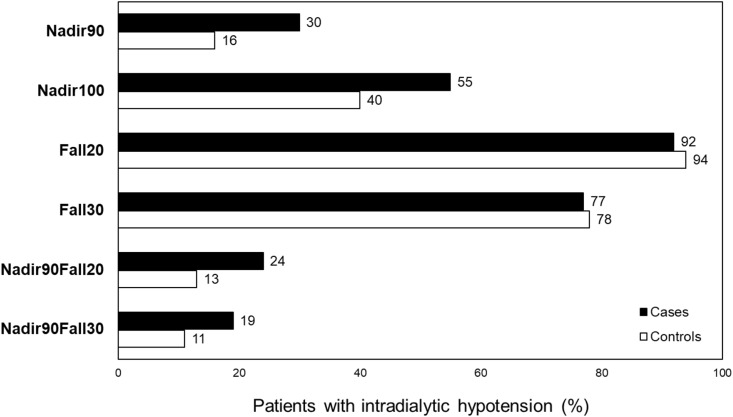

Patterns of IDH

The proportion of patients with IDH differed widely, depending on the definition used (Figure 2). For example, when IDH was defined as nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg (Nadir90), 30% of cases versus 16% of controls had IDH. In contrast, for definitions of IDH on the basis of a difference in predialysis SBP and nadir intradialytic SBP of at least 20 or 30 mm Hg (Fall20 and Fall30, respectively), the occurrence of IDH was much higher overall and occurred at similar rates among cases and controls.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients on hemodialysis with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (cases) and without hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (controls) with intradialytic hypotension, defined in six ways. The proportion of patients with intradialytic hypotension differed widely, depending on the definition used. Fall20, (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥20 mm Hg; Fall30, (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥30 mm Hg; Nadir90, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg; Nadir100, nadir intradialytic SBP <100 mm Hg; Nadir90Fall20, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg and (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥20 mm Hg; Nadir90Fall30, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg and (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥30 mm Hg.

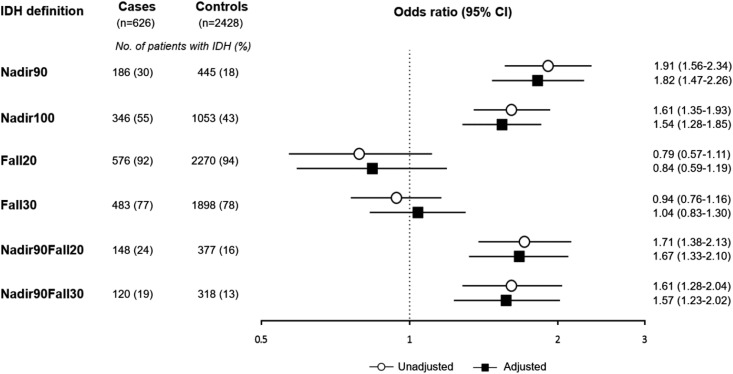

Association of IDH with Mesenteric Ischemia

Cases had a nearly two-fold higher odds of having had IDH in the 30 days before the index date compared with controls, when using a nadir-based IDH definition (i.e., Nadir90, Nadir100, Nadir90Fall20, and Nadir90Fall30; Figure 3). The magnitude of the association was similar across these four definitions. However, when IDH was defined using the two definitions that used the change in SBP without accounting for the absolute value of the nadir intradialytic SBP (i.e., Fall20 and Fall30), we observed no significant association of IDH and mesenteric ischemia. Adjustment for demographic and clinical factors did not significantly change the associations (Figure 3, Supplemental Table 2). We examined Nadir90-defined IDH in categories to assess for a dose-response association and found a direct association of proportion of IDH with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (Figure 4; P-trend <0.001).

Figure 3.

Odds of intradialytic hypotension (defined in six ways) among cases of hospitalized mesenteric ischemia and matched controls.Cases had a nearly two-fold higher odds of having had intradialytic hypotension in the 30 days before the index date compared with controls, when using a nadir-based IDH definition (i.e., Nadir90, Nadir100, Nadir90Fall20, and Nadir90Fall30). However, when using the two definitions that used the change in SBP (i.e., Fall20 and Fall30), there was no significant association of intradialytic hypotension and mesenteric ischemia. Adjustment for demographic and clinical factors did not significantly change the associations. Adjusted indicates adjusted for cause of ESKD, number of non-nephrology outpatient visits, hospital days, any nursing home stay, on the kidney transplant waiting list, all comorbidities, mean ultrafiltration rate, and central venous catheter use. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Fall20, (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥20 mm Hg; Fall30, (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥30 mm Hg; Nadir90, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg; Nadir100, nadir intradialytic SBP <100 mm Hg; Nadir90Fall20, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg and (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥20 mm Hg; Nadir90Fall30, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg and (predialysis SBP – nadir intradialytic SBP) ≥30 mm Hg.

Figure 4.

Association (odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals) of proportion of intradialytic hypotension (defined as Nadir90) with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia. To examine a potential dose-response association of intradialytic hypotension with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia, we categorized patients by the proportion of hemodialysis sessions having intradialytic hypotension, defined using the Nadir90 definition and found a direct association of proportion of intradialytic hypotension with hospitalized mesenteric ischemia (P-trend<0.001). Adjusted indicates adjusted for cause of ESKD, number of non-nephrology outpatient visits, hospital days, any nursing home stay, on the kidney transplant waiting list, all comorbidities, mean ultrafiltration rate, and central venous catheter use. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HD, hemodialysis; Nadir90, nadir intradialytic SBP <90 mm Hg.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted three sensitivity analyses, none of which materially changed the results: (1) we defined cases on the basis of acute mesenteric ischemia (Supplemental Figure 2); (2) we applied a uniform lookback window of 180 days before the index date to ascertain comorbid conditions (Supplemental Figure 3); (3) we restricted to patients with Medicare Part D, with adjusted models accounting for the number of antihypertensive medications used (Supplemental Figure 4, Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

Mesenteric ischemia is a rare medical emergency in the general population and associated with poor prognosis. Although still relatively uncommon at two to three events per 1000 person years in patients with ESKD on dialysis, the causative pathway may differ in these patients. Given the fact that the mortality rates associated with a mesenteric ischemia event in patients with ESKD can exceed 70% (2,5), identification of risk factors for mesenteric ischemia is of particular importance. Mesenteric ischemia in patients with ESKD on hemodialysis is most often due to nonocclusive disease (8,17), which could be triggered by systemic hypoperfusion, as would occur with IDH. In perhaps the largest study to date on this topic, we used the USRDS ESKD registry, enriched with detailed clinical data from a large dialysis organization, to identify 626 patients on hemodialysis with a hospitalized mesenteric ischemia event (cases) and matched them in a 1:4 ratio to 2428 controls. We report that cases have a nearly two-fold higher adjusted odds of having had IDH in the preceding 30 days, when using four different nadir-based IDH definitions compared with matched controls. Our results were robust to several sensitivity analyses.

Previous single-center case series and case reports have generally noted an association between hypotension and mesenteric ischemia. For example, a case-control study identified 15 cases of mesenteric ischemia in patients with ESKD on hemodialysis, matched with 30 controls from a single center in France (3). In that study, the mean pre- and postdialysis SBP was significantly lower in cases (116 and 88 mm Hg, respectively) than in controls (mean pre- and postdialysis SBP of 139 and 137 mm Hg, respectively). However, no information on IDH was provided in that study. In a separate single-center case series of 19 patients with ESKD on hemodialysis with a mesenteric ischemia event, 18 patients experienced hypotensive events in the dialysis session preceding the event, but the exact definition of hypotension was not described (18). Similarly, a case series of 29 patients from a large urban dialysis center with mesenteric ischemia reported that all patients had documented episodes of mean arterial pressure <60 mm Hg for 15–30 minutes at some point before the event, but further details on their BP patterns were not provided (8). Our results extend the results from these previous studies by studying a diverse group of patients on hemodialysis from across the United States, with detailed information on comorbid conditions as well as intradialytic hemodynamics.

Our results also integrate with the findings by McIntyre and colleagues, who hypothesized that hemodialysis-induced systemic circulatory stress and recurrent bowel ischemia may lead to increased endotoxin translocation from intestine (23,24). Their studies demonstrated that patients on hemodialysis have six-fold higher levels of circulating endotoxin than patients on peritoneal dialysis or with nondialysis-dependent patients with CKD, and that endotoxin levels were higher among patients with more dialysis-induced BP instability (23). Conversely, patients who had more frequent hemodialysis and less BP instability had lower circulating endotoxin levels (24).

Although IDH appears to be a potent risk factor for triggering mesenteric ischemia, it is not the only factor in patients with ESKD, as it has also been described in patients on peritoneal dialysis (25). Patients with ESKD share many of the predisposing factors for other causes of abnormal splanchnic vasculature, including hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia, advanced age, and heart failure (7,8,19). However, the large sample size allowed us to adjust for these other risk factors, and the association of IDH (identified using one of the four nadir-based definitions) with mesenteric ischemia persisted even after taking into account any differences in these characteristics between cases and matched controls.

Despite the fact that IDH is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in patients on hemodialysis, there is still no consensus definition of IDH. The National Kidney Foundation Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) suggests defining IDH as a decrease in SBP by ≥20 mm Hg or a decrease in mean arterial pressure by ≥10 mm Hg, with associated symptoms (26). The proportion of patients with IDH in our study differed widely depending on the definition used: from 19% to 92% of cases and from 11% to 94% of controls. The proportion of patients with IDH in our study was generally higher than among participants in the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study cohort, using the same definitions (15), possibly because the HEMO cohort excluded participants with severe heart failure, unstable angina pectoris, and serum albumin ≤2.6 g/dl. In that study, Flythe et al. showed that the nadir-based definitions of IDH had the strongest association with death, whereas definitions using change in SBP during dialysis or symptom-based criteria as suggested by KDOQI had no significant associations with death (15)—analogous to our findings on the association of IDH with mesenteric ischemia. Similarly, another recent study of 112,013 patients, initiating hemodialysis showed a direct linear relationship between IDH frequency, using a Nadir90 definition, and mortality (27). Moreover, in our study, the magnitude of the association of IDH with mesenteric ischemia was similar for the two simplest nadir-based definitions (nadir intradialytic SBP <90 or <100 mm Hg) as for the two definitions that also included the change in SBP. Taken together, these findings suggest that nadir-based definitions of IDH could provide clinicians with a simpler way to identify patients on hemodialysis who may be at particularly high risk for adverse events like mesenteric ischemia or death.

Our study has certain limitations. First, as with all observational studies, the potential for unmeasured confounding is possible. However, we selected up to four controls per case to improve statistical power and matched by not only calendar year and dialysis vintage, as longer dialysis vintage is risk factor of IDH (9) but also age, sex, race, CAD, PAD, and DM. We also adjusted for numerous measured confounders including ultrafiltration rate and comorbid conditions. Further, adjustment for a large number of factors barely changed the magnitude of the associations; thus, it is unlikely that any unmeasured or imperfectly measured factors would materially change our results. Second, identification of mesenteric ischemia using billing codes may be less reliable than using clinical information from the medical record. We sought to improve the specificity of the diagnosis code by requiring an abdominal imaging code (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) during the same hospitalization, but acknowledge that this approach has not been validated. Third, mesenteric ischemia was limited to patients who were severe enough to be hospitalized, and some patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia or with less severe disease may not have been identified. However, results were not materially changed in a sensitivity analysis restricted to patients with acute mesenteric ischemia. Fourth, subtypes of mesenteric ischemia, such as vascular occlusive or nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia, were not able to be ascertained.

In conclusion, we found that cases of patients hospitalized with mesenteric ischemia were significantly more likely than matched controls to have a recent history of IDH, as defined by nadir-based intradialytic SBP in the preceding 30 days. Given the difficulty in diagnosing mesenteric ischemia and the devastating outcomes associated with delayed recognition of this condition, patients with recurrent intradialytic SBP <100 mm Hg who have high risk for mesenteric ischemia should prompt consideration for mesenteric ischemia and targeted evaluation.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants K23DK095914 and R03DK113341 (to T.I.C.) and R01DK095024 (to W.C.W.) from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK, Bethesda, MA) and clinical research grant 2017 (to E.Y.S.) from Pusan National University Hospital.

The manuscript was reviewed and approved for publication by an officer of the NIDDK. Data reported herein were supplied by the US Renal Data System Interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Beware Intradialytic Hypotension: How Low Is Too Low?,” on pages 1453–1454.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13891217/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Clair DG, Beach JM: Mesenteric ischemia. N Engl J Med 374: 959–968, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li SY, Chen YT, Chen TJ, Tsai LW, Yang WC, Chen TW: Mesenteric ischemia in patients with end-stage renal disease: A nationwide longitudinal study. Am J Nephrol 35: 491–497, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassilios N, Menoyo V, Berger A, Mamzer MF, Daniel F, Cluzel P, Buisson C, Martinez F: Mesenteric ischaemia in haemodialysis patients: A case/control study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 911–917, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender JS, Ratner LE, Magnuson TH, Zenilman ME: Acute abdomen in the hemodialysis patient population. Surgery 117: 494–497, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoots IG, Koffeman GI, Legemate DA, Levi M, van Gulik TM: Systematic review of survival after acute mesenteric ischaemia according to disease aetiology. Br J Surg 91: 17–27, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han SY, Kwon YJ, Shin JH, Pyo HJ, Kim AR: Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia in a patient on maintenance hemodialysis. Korean J Intern Med (Korean Assoc Intern Med) 15: 81–84, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassiouny HS: Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia. Surg Clin North Am 77: 319–326, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John AS, Tuerff SD, Kerstein MD: Nonocclusive mesenteric infarction in hemodialysis patients. J Am Coll Surg 190: 84–88, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sands JJ, Usvyat LA, Sullivan T, Segal JH, Zabetakis P, Kotanko P, Maddux FW, Diaz-Buxo JA: Intradialytic hypotension: Frequency, sources of variation and correlation with clinical outcome. Hemodial Int 18: 415–422, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wanner C, Amann K, Shoji T: The heart and vascular system in dialysis. Lancet 388: 276–284, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton JO, Jefferies HJ, Selby NM, McIntyre CW: Hemodialysis-induced cardiac injury: Determinants and associated outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 914–920, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacEwen C, Sutherland S, Daly J, Pugh C, Tarassenko L: Relationship between hypotension and cerebral ischemia during hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2511–2520, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Vuolteenaho O, Lampainen E, Takala J: Splanchnic perfusion during hemodialysis: Evidence for marginal tissue perfusion. Crit Care Med 29: 1393–1398, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang TI, Paik J, Greene T, Desai M, Bech F, Cheung AK, Chertow GM: Intradialytic hypotension and vascular access thrombosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1526–1533, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flythe JE, Xue H, Lynch KE, Curhan GC, Brunelli SM: Association of mortality risk with various definitions of intradialytic hypotension. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 724–734, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stefánsson BV, Brunelli SM, Cabrera C, Rosenbaum D, Anum E, Ramakrishnan K, Jensen DE, Stålhammar NO: Intradialytic hypotension and risk of cardiovascular disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2124–2132, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valentine RJ, Whelan TV, Meyers HF: Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia in renal patients: Recognition and prevention of intestinal gangrene. Am J Kidney Dis 15: 598–600, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ori Y, Chagnac A, Schwartz A, Herman M, Weinstein T, Zevin D, Gafter U, Korzets A: Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia in chronically dialyzed patients: A disease with multiple risk factors. Nephron Clin Pract 101: c87–c93, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quiroga B, Verde E, Abad S, Vega A, Goicoechea M, Reque J, López-Gómez JM, Luño J: Detection of patients at high risk for non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia in hemodialysis. J Surg Res 180: 51–55, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YC, Hung SY, Wang HH, Wang HK, Lin CW, Chang MY, Ho LC, Chen YT, Wu CF, Chen HC, Wang WM, Sung JM, Chiou YY, Lin SH: Different risk of common gastrointestinal disease between groups undergoing hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis or with non-end stage renal disease: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 94: e1482, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sands BE, Duh M-S, Cali C, Ajene A, Bohn RL, Miller D, Cole JA, Cook SF, Walker AM: Algorithms to identify colonic ischemia, complications of constipation and irritable bowel syndrome in medical claims data: Development and validation. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 15: 47–56, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang TI, Shilane D, Kazi DS, Montez-Rath ME, Hlatky MA, Winkelmayer WC: Multivessel coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 2042–2049, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McIntyre CW, Harrison LE, Eldehni MT, Jefferies HJ, Szeto CC, John SG, Sigrist MK, Burton JO, Hothi D, Korsheed S, Owen PJ, Lai KB, Li PK: Circulating endotoxemia: A novel factor in systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 133–141, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jefferies HJ, Crowley LE, Harrison LE, Szeto CC, Li PK, Schiller B, Moran J, McIntyre CW: Circulating endotoxaemia and frequent haemodialysis schedules. Nephron Clin Pract 128: 141–146, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Archodovassilis F, Lagoudiannakis EE, Tsekouras DK, Vlachos K, Albanopoulos K, Fillis K, Manouras A, Bramis J: Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia: A lethal complication in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 27: 136–141, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Workgroup KD; K/DOQI Workgroup : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 45[Suppl 3]: S1–S153, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou JA, Streja E, Nguyen DV, Rhee CM, Obi Y, Inrig JK, Amin A, Kovesdy CP, Sim JJ, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Intradialytic hypotension, blood pressure changes and mortality risk in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33: 149–159, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.