CKD is a major public health issue in the United States, affecting nearly one in seven United States adults.1 This progressive condition is associated with high rates of comorbidity. For example, more than two thirds of Medicare patients older than 65 years old with CKD have cardiovascular disease, which is twice the prevalence in patients without CKD. Additionally, the annual mortality rate for Medicare patients with CKD (11.2%) is also twice that of Medicare patients without the disease. In 2015, total Medicare spending on patients with CKD exceeded $64 billion, >20% of the total Medicare budget. Furthermore, nearly nine in ten patients with CKD who progress to ESRD receive hemodialysis, which costs Medicare on average over $80,000 per patient per year.

As a result, CKD imposes a tremendous economic burden on the United States health care system. To stimulate and inform policy debate, we have identified and quantified potential savings resulting from improved care delivery interventions that are supported by the literature. We also propose several payment models to streamline—and reduce the cost burden of—care delivery to the estimated 30 million United States adults with CKD.

Effective interventions have been shown to improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care costs in patients with CKD. One of the factors believed to hasten progression of CKD to ESRD is delay in accessing nephrology care. Studies have shown that, compared with patients with a late referral to nephrology care before starting dialysis (1–6 months), patients with an early referral have slower rates of eGFR deterioration, have shorter hospital stays associated with dialysis initiation, are more likely to have a permanent vascular access and receive peritoneal dialysis, and have an approximately 30% lower mortality rate at 3 months and 5 years after dialysis initiation.2 Better management of the transition to RRT has also been shown to improve outcomes and save health care costs—for example, by decreasing the use of inpatient services and increasing the adoption of arteriovenous fistula, peritoneal dialysis, or preemptive kidney transplant.3,4

However, several barriers have prevented the current health care system from realizing the potential benefits of these practices. The suboptimal adoption of effective interventions is a complex and multifactorial phenomenon, which could be due to patients’ unwillingness to accept the diagnosis or prepare for RRT, providers’ unawareness of CKD clinical guidelines or inability to accurately predict the timing of RRT, and misaligned incentives or care fragmentation in the system. Although a comprehensive approach that covers all aspects of the problem is desired when resources allow, aligning incentives must be a primary goal of any public policies aiming to address the CKD epidemic. Motivated organizations or providers tend to actively seek information and develop and improve effective methods to engage patients, coordinate care, and improve outcomes.

One major example of suboptimal adoption of effective interventions is the failure to refer many Medicare patients with CKD to nephrologists early enough to slow progression. Among Medicare patients diagnosed with CKD stage 4 in 2014, nearly one third were not referred to a nephrologist in 2015.1 Non-Medicare payers covering younger patients may not be motivated to take steps to slow CKD progression, partly due to the difficulty in predicting the timing of ESRD and partly due to the belief that Medicare will eventually pick up the tab for dialysis or other RRT. One could argue that private payers should be incentivized to slow CKD progression and prepare patient transition to RRT, because they are responsible for the first 30 months of care for ESRD. However, the data suggest otherwise: among patients with incident ESRD in 2015, including those younger than 65 years old, about one quarter never received any nephrology care before the initiation of RRT, and only about one in five had permanent access via either an arteriovenous fistula or an arteriovenous graft.1 In both Medicare and non-Medicare patients, nearly two thirds of dialysis initiations occurred in an inpatient setting,5 which is the more costly option. Additionally, as of 2015, <3% of new patients with ESRD underwent a preemptive kidney transplant.1

To quantify the potential savings accruable as a result of rethinking care delivery for patients with CKD, we developed a cohort-level Markov model to simulate health care costs from a payer’s perspective. This model, on the basis of the published literature and educated assumptions, answers the following question: what would have happened in 2015 had certain interventions been implemented? We focused on patients with CKD stage 3 (eGFR=30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2), stage 4 (eGFR=15–29 ml/min per 1.73 m2), or stage 5 (eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2) who are not on RRTs yet, because the evidence on clinical benefits of care delivery interventions in patients with earlier-stage CKD has not been well established. We assigned a hypothetical cohort, derived from the 2017 US Renal Data System Annual Report,1 to two different strategies: the status quo that represents what happened in 2015 and the scenario that characterizes what would have happened under interventions. Specifically, we modeled the change in health care cost by implementing two interventions: (1) increasing the use of nephrology care before RRT to slow disease progression and (2) improving care coordination for the transition to RRT.

Because the simulation relies on key assumptions when data are not available from the published literature, it is, therefore, subject to several limitations. The cost savings may be underestimated because of a 1-year time horizon and the lack of data on private insurance costs, which are often higher than Medicare costs. Also, the patient population that we examined included only patients who were aware of their CKD diagnosis, and thus, the potential benefits of increased disease awareness in the future were not considered. We assumed that, for a well-run program, the rate of nephrology care would increase by 30% from the current rate and that the rate of preemptive transplant would increase to 6%, both of which are plausible but arbitrary figures. Lastly, the model parameters came from observational studies only, which typically used a nonrepresentative patient population and might have been confounded by potential biases. (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Material, and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 have more details).

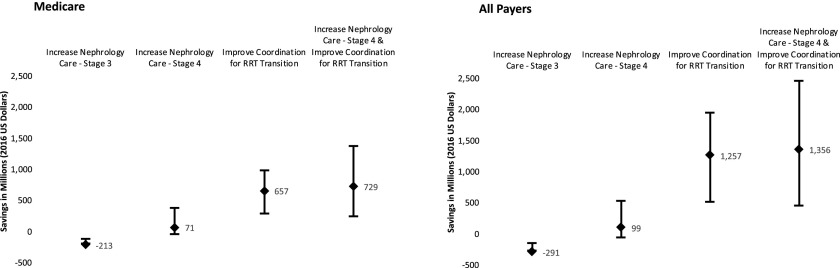

As illustrated in Figure 1, the model shows that increasing nephrology care for patients with CKD stage 3 nationwide does not generate net savings, whereas implementing the two interventions in patients with CKD stage 4 yields a net health care cost savings of $0.73 billion per year in 2016 United States dollars for Medicare alone (range, $0.25–$1.37 billion per year) and $1.36 billion per year for all payers (range, $0.45–$2.46 billion per year). More than 60% of net savings would come from reducing inpatient dialysis initiation. The savings potentially could be realized during the year that the interventions are implemented in all patients with advanced CKD (eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2) who are not on RRTs yet in the United States. Although it is plausible that there may be savings in earlier stages of CKD from a payer’s perspective, this is not supported by our analysis, which of course, is subject to the limitation that we examined only the savings within a 1-year time horizon.

Figure 1.

Improved CKD care management could generate a net healthcare cost savings of $0.73 billion and $1.36 billion per year for Medicare and all payers in the United States, respectively. The results are on the basis of a simulation of the effect of two interventions: (1) increasing pre-RRT nephrology care among patients with CKD stage 3 or 4 and (2) improving care coordination for the transition to RRT among patients with incident ESRD. The upper and lower bounds represent the range of net health care cost savings under the best case scenario and the worst case scenario, respectively. All costs have been adjusted for inflation to the 2016 United States dollars.

Several new payment models that align incentives across stakeholders can be used to realize such savings. As shown in the savings simulation, from a payer’s perspective, payment models ought to focus on patients with advanced CKD. Medicare could expand its use of chronic condition special needs plans to include all patients with advanced CKD. Such plans currently serve patients with ESRD but do not serve patients with advanced CKD who have not yet progressed to ESRD. Special needs plans contract with the Medicare program to provide all Part A, Part B, and/or Part D benefits for patients who have at least one of the designated chronic conditions, such as diabetes or ESRD. Because these plans are paid on a per-patient basis, they would be incentivized to take advantage of this low-hanging fruit to improve patient outcomes and reduce costs for Medicare patients.

Another option is to establish an episode-based payment model similar to the one proposed recently by the Renal Physicians Association.6 Such a model could focus on the care around the transition from advanced CKD to ESRD—for example, 6 months before and after dialysis initiation. Payments would be tied to the cost and quality of care. As a result, providers would be likely to invest in effective interventions to improve care management in patients with advanced CKD who have not progressed to ESRD. The magnitude of the potential savings from this model most likely would be similar to the amount shown in our simulation when we used a 1-year time horizon. The downside of an episode-based model is that it covers only a care episode for a predefined length of time, and therefore, the associated savings may not be as large as savings from other models.

Finally, Medicare and other payers could team up to establish a program to improve care for younger patients with advanced CKD who are not eligible for Medicare, because their condition has not yet progressed to ESRD. Under the current payment system, non-Medicare payers may perceive that investing in interventions to slow CKD progression will not benefit them, because they are responsible only for covering patients with ESRD resulting from CKD for a limited time. Because Medicare is the payer that eventually benefits the most from the savings resulting from slower CKD progression, these savings might be shared with non-Medicare payers. The goal is to incentivize non-Medicare payers to invest in CKD interventions to decrease the overall economic burden of CKD. At a minimum, Medicare should share cost savings to ensure that non-Medicare payers’ investments in such interventions are cost neutral.

The burden of CKD on patients and the health care system has been enormous. However, research has shown us that effective interventions and innovative payment models—if designed appropriately—have the potential to generate tremendous savings through improving care for patients with advanced CKD.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sydney Newberry for writing support. Great thanks also go to Dr. Andrew Allegretti from the Division of Nephrology of Massachusetts General Hospital for providing model parameter input regarding nephrology care.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Broadening Our Perspectives: CKD Care and the Dialysis Transition,” on pages 2605.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017121276/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System (USRDS): 2017 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smart NA, Dieberg G, Ladhani M, Titus T: Early referral to specialist nephrology services for preventing the progression to end-stage kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6: CD007333, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stroupe KT, Fischer MJ, Kaufman JS, O’Hare AM, Sohn MW, Browning MM, et al. : Predialysis nephrology care and costs in elderly patients initiating dialysis. Med Care 49: 248–256, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson DS, Kapoian T, Taylor R, Meyer KB: Going upstream: Coordination to improve CKD care. Semin Dial 29: 125–134, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Healthcare intensity at initiation of chronic dialysis among older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 143–149, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renal Physicians Association : Incident ESRD Clinical Episode Payment Model, Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2017 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.