Abstract

Background

The kidney proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) reabsorbs filtered macromolecules via receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME) or nonspecific fluid phase endocytosis (FPE); endocytosis is also an entry route for disease-causing toxins. PCT cells express the protein ligand receptor megalin and have a highly developed endolysosomal system (ELS). Two PCT segments (S1 and S2) display subtle differences in cellular ultrastructure; whether these translate into differences in endocytotic function has been unknown.

Methods

To investigate potential differences in endocytic function in S1 and S2, we quantified ELS protein expression in mouse kidney PCTs using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction and immunostaining. We also used multiphoton microscopy to visualize uptake of fluorescently labeled ligands in both living animals and tissue cleared using a modified CLARITY approach.

Results

Uptake of proteins by RME occurs almost exclusively in S1. In contrast, dextran uptake by FPE takes place in both S1 and S2, suggesting that RME and FPE are discrete processes. Expression of key ELS proteins, but not megalin, showed a bimodal distribution; levels were far higher in S1, where intracellular distribution was also more polarized. Tissue clearing permitted imaging of ligand uptake at single-organelle resolution in large sections of kidney cortex. Analysis of segmented tubules confirmed that, compared with protein uptake, dextran uptake occurred over a much greater length of the PCT, although individual PCTs show marked heterogeneity in solute uptake length and three-dimensional morphology.

Conclusions

Striking axial differences in ligand uptake and ELS function exist along the PCT, independent of megalin expression. These differences have important implications for understanding topographic patterns of kidney diseases and the origins of proteinuria.

Keywords: endocytosis, kidney anatomy, proximal tubule, proteinuria, Imaging

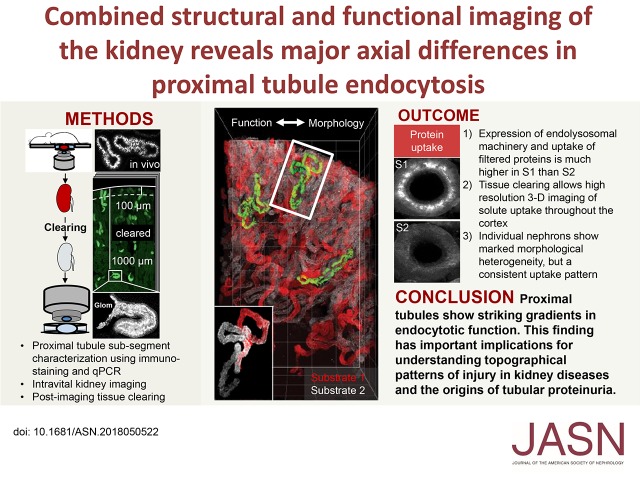

Visual Abstract

Adult humans filter approximately 170 L of fluid per day in the kidneys. Contained within the filtrate are hundreds of low mol wt proteins (LMWPs) and some albumin. Many of these LMWPs have important physiologic functions and need to be reclaimed to prevent urinary wasting. Reabsorption of proteins takes place by endocytosis in the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT), which is highly adapted to this purpose. Numerous insults—both genetic and acquired—can affect protein uptake in the PCT leading to elevated urinary levels, a condition known as tubular proteinuria, which can occur in isolation or as part of a generalized solute transport defect (renal Fanconi syndrome).1–5 Conversely, endocytosis provides an entry route into PCT cells for toxins that frequently cause kidney damage.6 Meanwhile, the detection of albuminuria is widely used as a screening test for glomerular pathology, but the role of the PCT in determining albumin excretion remains controversial.7 Therefore, to improve understanding of diseases in the PCT and the origins of proteinuria, it is first necessary to increase knowledge regarding normal handling of macromolecules by this nephron segment.

Uptake of macromolecules across the apical PCT cell membrane occurs via either specific receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME) or nonspecific fluid phase endocytosis (FPE).8 The main receptors for RME are megalin and cubilin, two large proteins that can bind a wide range of LMWPs9 and require adaptor proteins such as Disabled-2 (Dab2) for their normal function.10 Once internalized into early endosomes, proteins are trafficked to late endosomes and eventually lysosomes, to undergo degradation and/or transport to the baso-lateral membrane.7 The critical role of the endolysosomal system (ELS) in LMWP uptake and receptor recycling is illustrated by hereditary forms of renal Fanconi syndrome, such as Dent’s disease and Lowe syndrome, where the causative mutations have been localized to genes encoding proteins important for endosomal acidification and trafficking.11

The proximal tubule is classically divided into three segments (S1–3) on the basis of differences in cell ultrastructure, including the ELS, observable with electron microscopy (EM).12,13 S1 cells are found in the first part of the PCT after the glomerulus, S2 in the later PCT, and S3 exclusively in the straight portion. Whereas structural differences between S1 and S3 cells are quite striking, the differences between S1 and S2 cells are much subtler,13 and megalin is thought to be expressed in both segments,14 so whether there are significant functional differences between them in ligand uptake was unclear. Intravital multiphoton imaging of fluorescently labeled ligands offers the possibility to visualize renal solute handling in real time. This approach has been used in numerous previous studies to investigate albumin filtration and uptake,15–17 but less so to study LMWPs, partly due to a paucity of suitable labeled ligands. Moreover, depth of imaging is limited to the outer cortex and findings from superficial PCTs may not be representative.

Here, using intravital imaging and a variety of ligands—including LMWPs conjugated to very bright and photo-stable fluorophores—we show that uptake of protein by RME occurs almost exclusively in S1 PCT segments, which have a very high capacity for reabsorption and a far higher expression of ELS machinery. In contrast, uptake of dextrans via FPE occurs to a similar extent in S1 and S2. By utilizing a tissue-clearing approach, we show that it is possible to image solute uptake in PCTs at high resolution in large kidney sections, at depths way beyond what is achievable with intravital microscopy. Analysis of individually segmented nephrons revealed that LMWPs and dextrans show distinct reabsorption patterns throughout the cortex, but that PCTs show marked heterogeneity in three-dimensional morphology and solute uptake length. In summary, we present evidence of substantial axial differences in PCT ligand uptake and ELS function, independent of megalin expression, and that the S1 segment is highly specialized to reabsorb proteins via RME.

Methods

Dyes and Reagents

Both dextran and albumin were purchased prelabeled from the manufacturer (#D1976, #D22914, #A13100, #A34785; Thermo Fisher). Recombinant human lysozyme and β-lactoglobulin (#L1667, #L3908; Sigma-Aldrich) were labeled with either Atto-565 or Atto-647N, according the manufacturer’s protocol (#AD 565–31, #AD 647N-31; Atto-Tec). Labeled protein was purified using benchtop PD midiTrap G-25 Sephadex chromatography columns (#28–9180–08; GE Healthcare) and concentrated with 3-kD Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filters (#Z740186; Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. Purity and labeling ratio were measured by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry and absorption spectroscopy (Libra S70; Biochrom). Labeled solutes were dissolved in saline and injected intravenously in a volume of 0.12 ml. For control experiments with free dye, mice were injected with a mixture of unlabeled albumin (A7030; Sigma-Aldrich) and Alexa Fluor 488 carboxylic acid (A33077; Thermo Fisher Scientific), the inert nonreactive form of the dye, at the same concentrations used for labeled albumin. Monochlorobimane (MCB) (#635; AAT Bioquest) was dissolved in DMSO and injected as a 1-mg/ml solution.

Animals

All experiments were performed on 6–12-week-old male C57Bl/6J-Rj mice (supplied by Janvier, Le Genest, France), and were performed in accordance with the regulations of The Zurich Cantonal Veterinary Office. Unless stated otherwise, animals were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane (Attane; Provet AG, Switzerland) in 100 ml/min oxygen.

Antibody Staining in Fixed Kidney Tissue

Kidney tissue was perfusion fixed via the aorta with 3% paraformaldehyde in a phosphate-buffered solution. For lysozyme uptake experiments, Atto-565–labeled protein was injected via tail vein injection 1 hour before fixation. Immune staining was performed on 5-µm-thick cryosections incubated overnight with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-Rab5 (C8B1) (#3547; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-Rab11 (D4F5) (#5589; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-Rab7 (EPR7589) (ab137029; Abcam), rat anti-Lamp1 (1D4B) (ab25245; Abcam), mouse anti-Lrp2 (CD7D5) (NB110–96417; Novus Biologicals), polyclonal sheep anti-Cubilin (AF3700; R&D Systems), and rabbit anti-RBP4 (EP3657) (ab109193; Abcam). The following secondary conjugated antibodies were used (all at 1:500): Dylight488 goat anti-rat (A110–242D2; Bethyl Laboratories/Lubioscience), Alexa647 donkey anti-rabbit (711–606–152; Jackson ImmunoResearch), and AbberiorStar635-P goat anti-mouse (a kind gift from The Zurich Centre for Microscopy and Image Analysis). Brush border actin filaments were stained with ActinRed 555 ReadyProbes reagent (R37112; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were acquired using a Leica SP8 upright confocal microscope. To quantify signals, regions of interest were drawn around individual PCT segments in cortical labyrinths.

Gene Expression Analysis in Microdissected Tubular Segments

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg body wt; Streuli Pharma) and xylazine (20 mg/kg body wt; Streuli Pharma). The left kidney was perfused, removed, and cut into small pieces before incubation for 40 minutes at 37°C in a solution with 40 µg/ml liberase (Roche), containing: HBSS, HEPES 15 mM, D-glucose 10 mM, glycine 5 mM, and alanine 1 mM. Tubular segments were dissected on ice according to anatomic and morphologic characteristics (S1: PCTs that attach to glomeruli; S2: distal and thicker PCTs following from S1; S3: proximal straight tubules from the outer medullary region). Isolated tubules were lysed in the RNA extraction buffer from the RNAqueous Total RNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen). Total RNA was extracted immediately using the RNAqueous-Micro kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Ambion). Quality and concentration of the isolated RNA preparations were analyzed using the 2100 BioAnalyzer (RNA Pico chip from Agilent Technologies). Total RNA samples were stored at −80°C, and the same quantity of RNA was used to perform the reverse transcription reaction with iScript TM cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio Rad). Changes in target gene mRNA levels were determined by relative real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction with a CFX96TM Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad), using iQ TM SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) detection of single PCR product accumulation. RT-qPCR analyses were performed in duplicate with 100 nM of both sense and antisense primers in a final volume of 20 µl using iQTM SYBR Green Supermix. Specific primers were designed using Primer3 (Supplemental Table 1).18 The PCR products were sequenced with the BigDye Terminator kit (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems). The multiScreen SEQ384 Filter Plate (Millipore) and Sephadex G-50 DNA Grade Fine (Amersham Biosciences) dye terminator removal were used to purify sequence reactions before analysis on an ABI3100 capillary sequencer (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems). The relative changes in target gene/GAPDH mRNA ratio were determined using the 2ΔΔct formula.19

EM

Kidneys were perfusion fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in a phosphate-buffered solution via the abdominal aorta. Tissue was stored at 4°C overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, before fixation with 1% osmium tetroxide in cacodylate buffer. The samples were enhanced for contrast in 1% uranyl acetate, dehydrated with graded ethanol and 100% propylene oxide, and embedded in 100% Epon/Araldite. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were cut on an ultra-microtome (Reichert Ultracut), mounted on formvar-coated grids, and stained with lead citrate. Images were acquired with a CM 100 (FEI/Philips) equipped with a Gatan Orius 1000 CCD camera.

Intravital Imaging

The left kidney was externalized for imaging using previously established protocols.20 The internal jugular vein was cannulated to allow intravenous injections of dyes and reagents. Body temperature was monitored throughout experiments. Imaging was performed on a custom-built multiphoton microscope operating in an inverted mode.20 A broadband tunable laser (InSight DS Dual; Spectraphysics, Santa Clara) was used as excitation source. The following excitation wavelengths were used: MCB 780 nm, Cascade-blue 800 nm, Atto-565 850 nm, Alexa-488 950 nm, Alexa-647 and Atto-647N 1180 nm, and Alexa-680 1280 nm. Image processing was performed using FIJI and Imaris version 9.0 (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland). Starting shortly before intravenous injection of ligands, single plane intravital images were acquired every 15 seconds to visualize PCT handling in real time. Analysis of uptake was performed using images acquired 30–40 minutes postinjection, when the fluorescence signal from LMWPs or dextran was no longer detectable in the vasculature, thus signifying complete filtration of the molecules.

Urine Analysis

Urine samples from albumin-injected and control animals were separated by a 10% SDS-PAGE. Protein bands were visualized either by fluorescence using a Gel scanner ChemiDoc Touch (Biorad) with the settings for 488-nm dyes, or by Coomassie staining with ProtoBlue Safe (EC-722; National Diagnostics) and scanning with an Odyssey CLx gel scanner (Li-Cor).

Preparation and Imaging of Cleared Kidney Tissue

Tissue clearing was performed using a modified CLARITY approach.21 Kidneys were harvested immediately after intravital imaging experiments and were dissected transversally. Resulting sections were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C and incubated overnight in 4% acrylamide (161–0140; Bio-Rad) and 0.25% VA-044 (017–19362; Novachem) in PBS at 4°C. They were then incubated for 3 hours at 37°C for acrylamide polymerization, washed overnight in clearing solution (200 mM SDS (L3371; Sigma-Aldrich) and 200 mM boric acid (L185094; Sigma-Aldrich), pH 8.5), and electrophoresed in clearing solution using an X-CLARITY Tissue Clearing System (Logos Biosystems) for 8 hours at 1.5 A constant current, temperature<37°C, and 100 rpm pump speed. The sections were sectioned to 1-mm thickness, incubated in approximately 88% Histodenz (D2158; Sigma-Aldrich) solution in PBS (refractive index adjusted to 1.46) overnight, and mounted in the same solution. Imaging was performed on a TCS SP8 upright multiphoton microscope equipped with an NA 1.0 25× water objective, HyD-RLD detectors (Leica Microsystems, Germany), and an InSight DS Dual NIR laser tuned to 1040 (Atto 565 excitation) and 1250 nm (Alexa 647 excitation). The high-resolution data were preprocessed using Leica HyVolution2; all data were segmented and single nephrons were semiautomatically traced using Imaris v9.0 for the length calculations.

Statistical Analyses

All data were analyzed in Graphpad Prism 7. Differences in RNA data were investigated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Differences in fluorescence intensity were investigated with multiple t tests using the Holm–Sidak method.

Results

Expression of Endolysosomal Proteins, but Not Megalin, Is Higher in S1 than in S2

First, we used EM to confirm the existence of morphologic differences in the ELS between early (S1) and late (S2) PCT segments in our mice. S1 cells were characterized by the presence of large subapical vacuoles, whereas S2 cells contained electron-dense lysosomes (Supplemental Figure 1). Immuno-staining for the apical solute transporter NaPi2a revealed higher expression in early than in late PCT segments (Supplemental Figure 1), further supporting the notion that these are discrete transporting portions. To investigate axial patterns of ELS protein expression along the PCT, we performed both immuno-staining of fixed tissue and RT-qPCR gene expression analysis of microdissected segments. Expression of standard markers confirmed the purity of isolated tissue, and that S2 segments were discrete from S3 (Supplemental Figure 2).

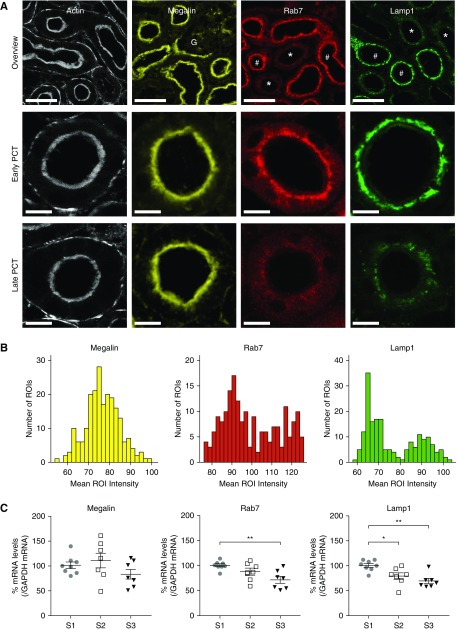

Both early and late PCT segments displayed a highly developed actin brush border (Figure 1A). Megalin expression was similar in all segments (Figure 1, A–C). In contrast, cubilin expression decreased from S1 to S3, but was highly variable in S2; however, the ratio of megalin-to-cubilin expression was significantly higher in S2 than in S1 (Supplemental Figure 3). Expression levels of the adaptor protein Dab2 and established markers for early endosomes (Rab5), late endosomes (Rab7), recycling endosomes (Rab11), and lysosomes (Lamp1)22 were all higher in S1, and Lamp1 expression correlated closely with that of NaPi2a (Figure 1, A–C, Supplemental Figure 3). Histograms of expression intensities in PCTs revealed a unimodal distribution for megalin, but bimodal for Rab7 and Lamp1, consistent with the existence of two discrete populations of tubules, most likely corresponding to S1 and S2 segments (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Expression of endolysosomal proteins is higher in early segments of the proximal tubule. (A) Immuno-staining of mouse kidney cortex revealed that all PCT segments displayed a highly developed actin brush border, and a similar expression level of megalin. In contrast, expression of Rab7 and Lamp1 was markedly higher in early (#) PCT segments than late (*). The identity of early segments was confirmed by their emergence from glomeruli (G). Scale bars, 50 μm in the top panel, and 10 μm in the lower panels. (B) To quantitatively analyze signal intensities, regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn around early or late sections of PCTs (in a total of three large field images), and mean intensity histograms for each segment are depicted. The histograms for Rab7 and Lamp1 expression showed bimodal distributions, corresponding to early and late segments, whereas megalin expression showed a unimodal distribution. (C) Gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR confirmed that megalin expression was similar in all proximal tubule segments. In contrast, Rab7 and Lamp1 expression decreased from S1 to S3 (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

Expression of ELS proteins within cells in early PCT segments was observed predominantly in the subapical region (Figure 2A). In contrast, in late segments the distribution of ELS proteins was more diffuse. To confirm this impression, we calculated the SD of signal intensity distributions within individual PCT cells. Using this approach, we found that the SDs of signal intensities for Rab7 and Lamp1 showed bimodal distributions and a close correlation (Figure 2B). In contrast, the SD for megalin showed a unimodal distribution, and did not correlate with either Rab7 or Lamp1.

Figure 2.

Expression patterns of endolysosomal proteins within cells differ between early and late segments of the proximal tubule. (A) Analysis of signal intensity across PCTs cut in cross-section revealed that expression of the endolysosomal proteins Rab7 and Lamp1 was concentrated predominantly in the subapical region of cells in early segments, but was relatively uniform across cells in later segments. In contrast, megalin was expressed in the apical brush border region of all PCT segments. Scale bars, 10 μm. The plots (bottom panels) depict the cumulative intensity profiles for the segments drawn in the top panels. The segments have different lengths and were therefore normalized to arbitrary units (AU), with 0 being the baso-lateral side of the cell (BL), and 1 the apex (Ap). (B) The SD of the Lamp1 signal within regions of interest drawn around sections of PCTs correlated closely with that of Rab7 (R=0.93; P<0.001), and two distinct clusters were observed, corresponding to early (solid line) and late (dashed line) segments, respectively. In contrast, no positive correlation was observed between the SD of the Lamp1 and megalin signals (R=−0.47; P<0.001).

In summary, we found evidence of striking axial differences in expression levels and subcellular distribution of key ELS proteins along the PCT, independent of megalin expression, which supports the existence of two discrete functional segments (i.e., S1 and S2), and could point to major differences in ligand uptake capacity.

Uptake of Filtered Proteins by RME Occurs Almost Exclusively in S1

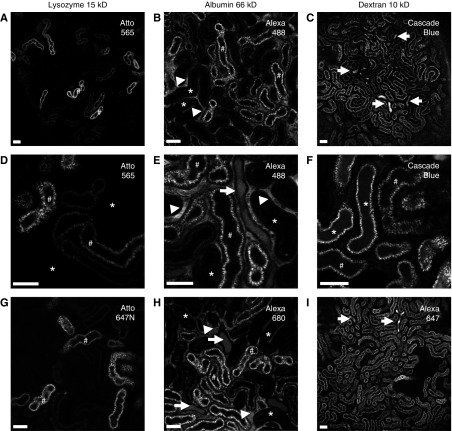

To investigate functional uptake of filtered molecules via endocytosis in the PCT, we used intravital multiphoton microscopy and intravenous injections of three different fluorescently labeled ligands: (1) lysozyme, a 14-kD LMWP that is rapidly filtered, and is a classic ligand for megalin-mediated RME23; (2) albumin, a large protein that is only partially filtered, and then taken up by RME via megalin and the FcRn receptor7; and (3) a small dextran (10 kD), which is rapidly filtered and taken up by FPE. Commercially available prelabeled forms of albumin and dextran were used. To label lysozyme we used atto dyes, which are extremely bright and highly photo-stable,24 thus enabling high-resolution imaging in vivo. Experiments with each ligand were repeated with two different labels to exclude a confounding effect of the fluorophores on uptake.

At an injected amount of 10 µg, which should result in a plasma concentration >100× physiologic levels,25 we observed that lysozyme disappeared rapidly from the vasculature (within 30 minutes), consistent with glomerular filtration. Regardless of the fluorescent label used, subsequent uptake of lysozyme occurred exclusively in S1 PCT segments, with no observable distal tubular wasting (Figure 3, A, D, and G). To exclude the possibility that lysozyme is not representative of other LMWPs, we also injected fluorescently labeled β-lactoglobulin, which showed a similar uptake pattern (Supplemental Figure 4). Organic anion transport is a specialized function of S2 and can be measured using MCB, which forms a fluorescent adduct with intracellular thiols.26 We observed an increased transport of MCB in lysozyme-negative PCT segments (Supplemental Figure 4), consistent with an S2 identity. The identity of S1 and S2 PCT segments was also confirmed by their characteristic autofluorescence patterns (Supplemental Figure 4).27

Figure 3.

Intravital microscopy reveals different uptake patterns for proteins and dextrans in the proximal tubule. Real-time intravital multiphoton imaging of solute handling in the kidney revealed that the proteins lysozyme (A, D, and G) and albumin (B, E, and H), which are both substrates for RME, were predominantly reabsorbed in S1 (#) PCTs. In contrast, dextran (10 kD) (C, F, and I), a marker for FPE, was taken up in both S1 and S2 (*) segments. Albumin was visible in the vasculature far longer than the smaller molecules (arrowheads), consistent with a slower rate of filtration. Luminal wasting of albumin and dextran in distal tubules was observed (arrows), but not lysozyme. Two different fluorescent markers were used for each solute. Images were acquired 30–40 minutes postinjection. Scale bars, 50 µm.

Albumin was injected at an amount of 500 µg, on the basis of previous studies suggesting this is sufficient to observe PCT uptake in vivo in rodents.28 As expected, albumin remained visible in the vasculature far longer than lysozyme, consistent with a slow rate of filtration. Uptake of albumin also occurred predominantly in S1 segments, with very little S2 uptake observed (Figure 3, B, E, and H). To exclude the possibility that the uptake in S1 reflected free dye cleaved in the circulation, we performed injections of the dye alone, which only revealed a very low level of uptake (Supplemental Figure 5). Despite the relatively slow rate of albumin filtration, fluorescence signal was clearly observed in distal tubule lumens, consistent with wasting of either labeled albumin or cleaved free dye. We were unable to detect evidence of intact fluorescently labeled albumin on gel electrophoresis of urine samples collected from injected mice. However, by Coomassie stain both albumin-injected and control mice displayed bands consistent with urinary albumin excretion (Supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that the uptake capacity in vivo is close to the filtered load.

Uptake of 10-kD dextran was found to be far less efficient than that of proteins, with prominent distal tubular wasting, and despite rapid filtration a relatively high amount of 300 µg was required to clearly visualize uptake in PCT cells. In stark contrast to the proteins, reabsorption of dextran occurred in S1 and S2 segments at a similar level (Figure 3, C, F, and I), suggesting that FPE occurs in both.

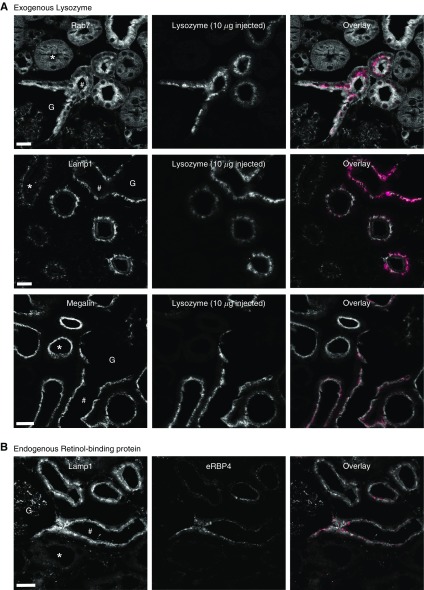

Uptake of Lysozyme in the Proximal Tubule Matches the Expression of Endolysosomal Proteins

To further investigate the anatomic relationship between LMWP uptake and the expression of ELS proteins in the PCT, we perfusion fixed kidneys from mice 1 hour post injection of lysozyme. Using this approach, we confirmed that lysozyme uptake occurred in S1 segments, matching the high expression of Rab7 and Lamp1 in this region (Figure 4A). In contrast, in spite of clear evidence of megalin expression, we did not observe lysozyme signal in late segments. To exclude the possibility that exogenous injected LMWPs are handled differently from endogenous ligands, we performed immuno-staining for endogenous retinol-binding protein (RBP4), which localized exclusively to early S1 segments (Figure 4B, Supplemental Figure 4). Thus, the uptake pattern of LMWPs matches the expression of ELS machinery, rather than that of megalin.

Figure 4.

Protein uptake occurs in regions of proximal tubules with high expression of endolysosomal proteins. (A) One hour post intravenous injection of fluorescently labeled lysozyme, kidneys were perfusion fixed and stained for endolysosomal markers and megalin. Lysozyme (magenta in overlay) was visible in the subapical region of early (#) PCT cells expressing high levels of Rab7 and Lamp1. No uptake was detected in late (*) PCT segments, where expression levels of these markers were low, in spite of a high expression of megalin. Early segments could be observed directly leaving the glomerulus (G), thus confirming their identity. (B) Immuno-staining for the endogenous protein retinol-binding protein (RBP4, magenta in overlay) also revealed an early S1 localization. Scale bars, 10 μm.

S1 Proximal Tubule Segments Have a Very High Capacity for Lysozyme Uptake

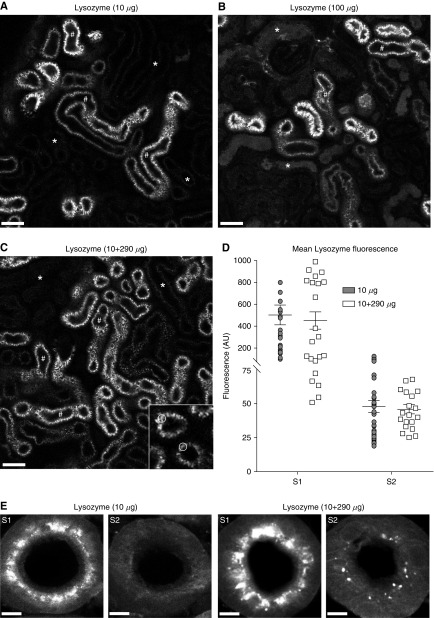

Because the uptake of lysozyme is apparently highly efficient in S1 PCT segments, we considered that significant S2 uptake might only occur under conditions when S1 uptake is saturated. To investigate this, we injected a 10× higher dose of labeled lysozyme (100 µg), which rapidly disappeared from the vasculature, suggesting no rate-limiting effect of glomerular filtration. At this high amount we again observed reabsorption predominantly in S1 segments (Figure 5, A and B), and although some lysozyme wasting was observed in more distal nephron segments, uptake in S2 remained minimal. Because of practical issues with saturation of fluorescence signals, we were not able to use injections of labeled lysozyme >100 µg. Because we established that 300 µg was the maximum dose that the animals could tolerate without showing an adverse reaction, to further increase lysozyme delivery we injected a combination of 290 µg unlabeled and 10 µg labeled. Even at this very high amount, uptake levels in S1 and S2 were similar to injecting 10 µg alone (Figure 5, C and D), and high-resolution confocal imaging in fixed tissue confirmed minimal lysozyme signal in S2 (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

The S1 segment of the proximal tubule has a very high capacity for protein uptake. (A–D) Intravital imaging of lysozyme uptake in the PCT in vivo. (A) After intravenous injection of 10 µg of fluorescently labeled lysozyme, uptake was only observed in S1 segments (#). (B) Uptake remained predominantly in S1 (#) after a 10× higher injection. At this dose some luminal wasting was observed, but uptake in S2 PCT cells (*) remained low. (C and D) At an even higher dose of lysozyme (10 µg labeled+290 µg unlabeled), uptake patterns in S1 (#) and S2 (*) were similar to the 10-µg injection. Data depicted are mean fluorescence intensities within regions of interest in the apical vesicles of PCT cells (insert in (C)). The intensity values in S2 segments predominantly reflect nonspecific background fluorescence signals. AU, arbitrary units. (E) High-resolution confocal microscopy of fixed kidney specimens 1 hour post injection of lysozyme confirmed that uptake was predominantly confined to S1, with only a small level of uptake detectable in S2 at 300 µg. Scale bars, 50 µm in (A–C), and 5 µm in (E).

In summary, our findings suggest that the S1 PCT segment has a very high capacity for LMWP reabsorption that is way beyond the normal filtered load, but that very little uptake occurs in S2 segments even under saturating conditions.

Three-Dimensional Imaging of Solute Uptake in the Kidney Cortex Using Tissue Clearing

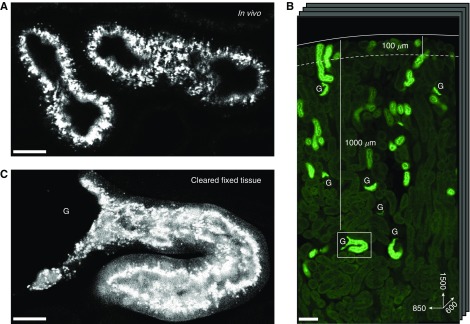

A major constraint of intravital kidney microscopy is that the depth of imaging is limited to the very outer cortex. We therefore developed a new protocol, whereby upon completion of intravital experiments the very same kidneys were fixed and chemically cleared to increase transparency, while retaining the fluorescence signal from ligands taken up by PCTs. We were then able to image solute uptake at single-organelle resolution throughout the full thickness of the cortex in three dimensions, at depths approximately 10× the normal limit of intravital microscopy (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Tissue clearing allows high resolution imaging of lysozyme uptake in deep proximal tubules. (A) Example image of lysozyme uptake in superficial PCTs, 35 µm below the capsule, acquired using intravital microscopy. (B) Overview of a 1500×850×600-µm section of the same kidney after fixation and tissue clearing, showing lysozyme uptake in PCTs throughout the entire thickness of the cortex. The dotted line denotes the typical depth of imaging limit for intravital microscopy (100 µm). (C) High-resolution imaging of a single glomerulus and early PCT segment from (B), approximately 1000 µm below the organ surface, showing single endosomes containing lysozyme. Scale bars, 20 µm in (A and C), and 100 µm in (B). G, glomeruli.

Using this approach, we could confirm that the basic pattern of solute uptake observed in superficial nephrons held true throughout the cortex; namely, lysozyme uptake was localized exclusively to early PCT segments, whereas dextran was also reabsorbed in later segments (Figure 7, A–C, Supplemental Material). Moreover, detailed imaging of the uptake pattern of lysozyme along individually segmented nephrons typically revealed a distinct cut-off region beyond which signal was no longer visible, suggesting a step change in function at the S1/S2 interface. Quantitative analysis revealed that the length of lysozyme uptake ranged from 600 to 1100 µm within a single kidney, whereas dextran uptake length ranged from 900 to 2600 µm (Figure 7, D and E). After a 10× larger lysozyme injection (10 µg labeled plus 290 µg unlabeled), the histogram uptake length was only slightly right shifted, providing further evidence against a substantial increase in S2 uptake (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Quantification of PCT uptake lengths in cleared kidney tissue reveals differences between lysozyme and dextran. (A) Combined imaging of lysozyme (red) and dextran (white) revealed that uptake patterns in PCTs were markedly different throughout the entire thickness of the kidney cortex. (B and C) High-resolution imaging of three individually segmented PCTs from (A), showing that uptake of lysozyme typically ends abruptly, but that uptake of dextran continues beyond this point (* denotes the position of the glomerulus). (D and E) Histograms of PCT uptake lengths for both lysozyme and dextran revealed considerable heterogeneity within the same kidney (n=18 tubules). Scale bars, 200 µm in (A), and 100 µm in (B and C).

Figure 8.

PCTs show striking heterogeneity in three-dimensional structure. (A) Overview image of a kidney section showing uptake of lysozyme in PCTs after a high-dose injection (300 µg). (B) Segmentation of individual PCTs from superficial (a–c), intermediate (d–f), and deep (g and h) cortical regions from (A) revealed evidence of considerable heterogeneity in three-dimensional structure. Highly convoluted tubules were typically found in superficial regions, whereas more elongated tubules were located in deeper regions. (C) Histogram of lysozyme uptake length in PCTs within the same kidney (n=61 tubules). (D) Quantitative morphometrics of three segmented PCTs from (A) demonstrating the effect of three-dimensional structure on the space-occupying volume (bounding box). Scale bars, 200 µm. h, height, w, width, d, depth.

In addition to variable uptake length of solutes, individually segmented PCTs displayed striking heterogeneity in three-dimensional morphology, with some being highly convoluted, whereas others were relatively straight, leading to major differences in space-occupying volume (Figure 8, Supplemental Material). PCTs characterized morphologically by an elongation in the cortico-medullary axis of the space-occupying volume were typically found in deeper regions of the cortex, whereas PCTs occupying a more symmetrical space were typically located superficially.

In summary, using tissue clearing it is possible to image the uptake of different solutes at high resolution throughout the entire thickness of the cortex, which provides substantial additional information compared with standard intravital imaging approaches.

Discussion

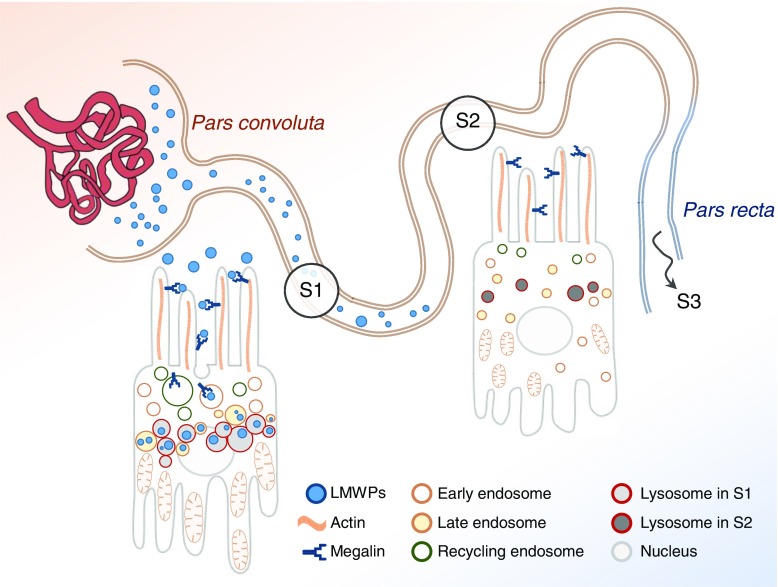

Reabsorption of filtered macromolecules by endocytosis is a major function of the PCT, and impairment of this process is the hallmark of the many forms of renal disorders. Moreover, endocytosis provides an entry route for toxins that cause kidney damage. Using fluorescently labeled ligands and novel imaging approaches we have discovered evidence of major axial differences in PCT ligand uptake and ELS function. We found that, although megalin is expressed along the PCT, uptake of both albumin and LMWPs by RME occurred almost exclusively in S1, which closely matched a much higher expression of ELS machinery in this segment (Figure 9). In contrast, uptake of FPE substrates occurred along the entire PCT. Moreover, using tissue clearing, we showed that these basic patterns are preserved throughout the renal cortex, but that individual PCTs are highly heterogeneous in terms of ligand uptake length and three-dimensional morphology. These findings have important implications for understanding integrated structure and function of the PCT in vivo.

Figure 9.

Proximal tubules display axial differences in ELS structure and function. The majority of uptake of filtered LMWPs occurs in the cells of the S1 segment of the proximal tubule, which are specialized to perform this task and express high levels of ELS proteins. Relatively little LMWP uptake occurs in S2 cells, which accordingly display a much lower expression of endolysosomal proteins.

The PCT represents a highly specialized transporting epithelium, which is responsible for reabsorbing and transporting a range of different solutes. Axial differences in expression levels of sodium-coupled transporters and organic anion/cation transporters are well recognized,29,30 suggesting differences in function between the subsegments. Consistent with this, older micropuncture studies revealed that the bulk of fluid reabsorption postfiltration occurs in S1.31 Recent studies have also reported variation in transcriptomes32 and metabolic autofluorescence signals along the PCT.33 However, although differences in the ultrastructure of the ELS between S1 and S2 cells have been described,13 and could be observed in our mice by EM, these are fairly subtle. Both segments have a highly developed apical brush border and express megalin, and the vast majority of studies of endocytosis have considered the PCT as a single entity.32 Therefore, it was previously unclear whether there are significant axial differences in ELS function, and to what extent RME and FPE play discrete roles in ligand uptake.

In this study, we used lysozyme as an archetypal LMWP, because it is an endogenous plasma protein that has a high glomerular-sieving coefficient,34 and is an established ligand for megalin.23 To visualize uptake at high resolution in vivo we labeled lysozyme with very bright and photo-stable fluorophores.24 We found that uptake of lysozyme and albumin occurred almost exclusively in S1 segments. Although it is somewhat intuitive that uptake of filtered molecules would be higher in the first segment immediately after the glomerulus, the magnitude of the S1/S2 differences was surprising. Moreover, S2 uptake did not increase substantially even when S1 uptake was saturated and the delivery of filtered proteins was increased. These observations point to a step change in function between two discrete and specialized segments, a concept that was further reinforced by a bimodal distribution of key ELS proteins. Previous studies have described higher expression of lysosomal proteases in S1 segments in rats35 and a low uptake of lysozyme in perfused S2 segments isolated from rabbits,36 suggesting these differences are not unique to mice.

Given that both S1 and S2 segments express megalin, the reason(s) for the low uptake capacity in S2 are currently unclear, but possible explanations from our data include a decreased cubilin-to-megalin ratio and a decreased expression of the adaptor protein Dab2. Of note, a recent study has suggested that knockdown of Dab2 in PCT cells leads to a decrease in endocytosis and alterations in Rab5 and Rab7 expression.37 At present, we can only speculate as to the role of megalin in S2 cells, but it might be important in facilitating the trafficking of transporters to and from the apical membrane.38

Our experiments suggest that the S1 segment has a very high capacity to reabsorb LMWPs, far exceeding the normal filtered load, perhaps to prevent urinary wasting when plasma levels and/or filtration rapidly increase. In contrast, in spite of a much lower glomerular-sieving coefficient, we observed evidence of albumin wasting, which is in agreement with previous studies suggesting that the maximal capacity for albumin reabsorption is close to the normal filtered load.34 Because filtered proteins have to pass through the dense apical brush border to come into contact with membrane invaginations in PCT cells and undergo internalization, size and charge could play rate-limiting roles in determining the overall efficiency of the uptake process.39 The uptake of dextran in PCTs was considerably lower than that of proteins, consistent with previous experiments using radio-labeled ligands in rats,40 suggesting that RME is a far more efficient uptake process than FPE in vivo. In contrast to proteins, we found clear evidence of dextran uptake in both S1 and S2 segments, suggesting that capacity for FPE is similar along the PCT. However, because most fluid reabsorption occurs in S1, the luminal concentration of dextran may be increased by S2, which could also contribute to the high uptake in this region.

Our findings have several important implications for understanding kidney diseases. First, because LMWP uptake occurs predominantly in S1, by extrapolation it is likely that patients with tubular proteinuria have damage in this segment. We did not observe evidence of compensatory uptake in S2 when S1 uptake was acutely saturated, but it is possible that some axial plasticity might occur in disease states where S1 function is chronically impaired,41 perhaps initiated by binding to megalin in S2. A very recent study suggested that knockdown of megalin in S1 and S2 leads to a downstream increase in S3 uptake, but this has only a minimal effect on protein excretion.42 Second, the very high capacity for LMWP uptake in S1 reinforces the need for biomarkers that can detect PCT damage at an early stage, before the appearance of proteinuria.43 Finally, axial differences in uptake could determine various topographic patterns of damage observed in response to certain toxins, such as endotoxin,27 light chains,44 contrast agents, and volume expanders.45

A major historical problem for intravital kidney microscopy has been the limited depth of imaging possible. We showed previously that this can be increased by using far red excitation and probes,20 but even with this improvement the majority of cortex remains beyond view. Tissue-clearing techniques substantially increase transparency and have been used recently in the kidney to assess total glomerular number and structural damage in PCTs from cisplatin.46,47 The major practical challenge with such approaches is to retain fluorescence signals and directly relate structural information to functional readouts. We have developed a protocol whereby the fluorescence signal from labeled solutes taken up by the PCT is still preserved postclearing. Individual nephrons can then be segmented to quantitatively investigate how cellular ligand uptake relates to the three-dimensional architecture of the organ. Moreover, findings can be directly crossreferenced to dynamic observations made from intravital imaging in the very same organ.

Using this approach, we confirmed that uptake patterns of protein and dextran are markedly different along nephrons throughout the entire cortex. However, individual PCTs displayed striking heterogeneity in solute uptake length and three-dimensional morphology, demonstrating that substantial additional information can be acquired with this methodology. We observed a relatively sharp cut-off point between protein and dextran uptake, probably corresponding to the interface of S1/S2, but in the absence of definitive anatomic markers we cannot be sure of this. Nevertheless, by continuously following individual PCTs from the glomerulus we could show that in most cases protein uptake is limited to the initial 1 mm or so. Uptake distance was typically greater in deeper than in superficial PCTs, consistent with previous micropuncture studies suggesting that GFR is higher in juxtamedullary nephrons.48 Our findings illustrate that tissue-clearing techniques have huge future potential for the quantitative study of kidney structure and function. Elegant previous attempts to study three-dimensional nephron morphology have relied on reconstruction from serial two-dimensional images,49 which is demonstrably possible, but considerably more labor intensive.

Our study has several potential limitations. First, the process of labeling solutes with fluorescent molecules could alter their uptake in the kidney.50 Second, although we have studied several ligands for RME, including both endogenous and exogenous proteins, our findings might not be representative of all LMWPs, because size and charge can play important roles in the efficiency of uptake. Moreover, we cannot currently explain why megalin and cubilin are expressed in S2. Third, tissue clearing can lead to swelling of the kidney, which could affect the accuracy of morphologic measurements. Finally, our experiments were performed in male mice and might not be applicable to females or other species.

In summary, we have found new evidence of major axial differences in PCT ligand uptake and ELS function, which have important implications for understanding topographic patterns of kidney diseases, the origins of proteinuria, and how individual cell function relates to the complex three-dimensional architecture of the organ.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Huguette Debaix, Andres Kaech, and Monique Carrel.

A.M.H. is supported by The Swiss National Centre for Competence in Research Kidney Control of Homeostasis and by a Swiss National Science Foundation project grant (31003A 166507). O.D. is supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation project grant (31003A 169850). The authors also acknowledge support from The Clinical Research Priority Program “Molecular Imaging Network Zurich,” and The Zurich Centre for Integrative Human Physiology.

C.D.S., D.H., O.D., U.Z., and A.M.H. designed the study. C.D.S., M.P., E.P., A.G., N.T., S.G., and M.B. carried out experiments. C.D.S., M.P., E.P., D.H., A.G., N.T., and S.G. analyzed the data. A.M.H. drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2018050522/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sirac C, Bridoux F, Essig M, Devuyst O, Touchard G, Cogné M: Toward understanding renal Fanconi syndrome: Step by step advances through experimental models. Contrib Nephrol 169: 247–261, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall AM, Bass P, Unwin RJ: Drug-induced renal Fanconi syndrome. QJM 107: 261–269, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klootwijk ED, Reichold M, Unwin RJ, Kleta R, Warth R, Bockenhauer D: Renal Fanconi syndrome: Taking a proximal look at the nephron. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 1456–1460, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherqui S, Courtoy PJ: The renal Fanconi syndrome in cystinosis: Pathogenic insights and therapeutic perspectives. Nat Rev Nephrol 13: 115–131, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Festa BP, Chen Z, Berquez M, Debaix H, Tokonami N, Prange JA, et al.: Impaired autophagy bridges lysosomal storage disease and epithelial dysfunction in the kidney. Nat Commun 9: 161, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA: Gentamicin traffics retrograde through the secretory pathway and is released in the cytosol via the endoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F617–F624, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickson LE, Wagner MC, Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA: The proximal tubule and albuminuria: Really! J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 443–453, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eshbach ML, Weisz OA: Receptor-mediated endocytosis in the proximal tubule. Annu Rev Physiol 79: 425–448, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen R, Christensen EI, Birn H: Megalin and cubilin in proximal tubule protein reabsorption: From experimental models to human disease. Kidney Int 89: 58–67, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosaka K, Takeda T, Iino N, Hosojima M, Sato H, Kaseda R, et al.: Megalin and nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA interact with the adaptor protein Disabled-2 in proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int 75: 1308–1315, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devuyst O, Luciani A: Chloride transporters and receptor-mediated endocytosis in the renal proximal tubule. J Physiol 593: 4151–4164, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maunsbach AB: Observations on the segmentation of the proximal tubule in the rat kidney. Comparison of results from phase contrast, fluorescence and electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res 16: 239–258, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen EI, Wagner CA, Kaissling B: Uriniferous tubule: Structural and functional organization. Compr Physiol 2: 805–861, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen EI, Birn H, Storm T, Weyer K, Nielsen R: Endocytic receptors in the renal proximal tubule. Physiology (Bethesda) 27: 223–236, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salmon AH, Ferguson JK, Burford JL, Gevorgyan H, Nakano D, Harper SJ, et al.: Loss of the endothelial glycocalyx links albuminuria and vascular dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1339–1350, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandoval RM, Wagner MC, Patel M, Campos-Bilderback SB, Rhodes GJ, Wang E, et al.: Multiple factors influence glomerular albumin permeability in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 447–457, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner MC, Campos-Bilderback SB, Chowdhury M, Flores B, Lai X, Myslinski J, et al.: Proximal tubules have the capacity to regulate uptake of albumin. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 482–494, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rozen S, Skaletsky H: Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132: 365–386, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD: Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuh CD, Haenni D, Craigie E, Ziegler U, Weber B, Devuyst O, et al.: Long wavelength multiphoton excitation is advantageous for intravital kidney imaging. Kidney Int 89: 712–719, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H, Park JH, Seo I, Park SH, Kim S: Improved application of the electrophoretic tissue clearing technology, CLARITY, to intact solid organs including brain, pancreas, liver, kidney, lung, and intestine. BMC Dev Biol 14: 48, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wandinger-Ness A, Zerial M: Rab proteins and the compartmentalization of the endosomal system. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6: a022616, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leheste JR, Rolinski B, Vorum H, Hilpert J, Nykjaer A, Jacobsen C, et al.: Megalin knockout mice as an animal model of low molecular weight proteinuria. Am J Pathol 155: 1361–1370, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han Y, Li M, Qiu F, Zhang M, Zhang YH: Cell-permeable organic fluorescent probes for live-cell long-term super-resolution imaging reveal lysosome-mitochondrion interactions. Nat Commun 8: 1307, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Zheng F, Li Z, Uribarri J, Ren B, Hutter R, et al.: Reduced acute vascular injury and atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice transgenic for lysozyme. Am J Pathol 169: 303–313, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller DS, Letcher S, Barnes DM: Fluorescence imaging study of organic anion transport from renal proximal tubule cell to lumen. Am J Physiol 271: F508–F520, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalakeche R, Hato T, Rhodes G, Dunn KW, El-Achkar TM, Plotkin Z, et al.: Endotoxin uptake by S1 proximal tubular segment causes oxidative stress in the downstream S2 segment. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1505–1516, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA: Intravital multiphoton microscopy as a tool for studying renal physiology and pathophysiology. Methods 128: 20–32, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mather A, Pollock C: Glucose handling by the kidney. Kidney Int Suppl 79[Suppl 120]: S1–S6, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Launay-Vacher V, Izzedine H, Karie S, Hulot JS, Baumelou A, Deray G: Renal tubular drug transporters. Nephron, Physiol 103: 97–106, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddox DA, Gennari FJ: The early proximal tubule: A high-capacity delivery-responsive reabsorptive site. Am J Physiol 252: F573–F584, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JW, Chou CL, Knepper MA: Deep sequencing in microdissected renal tubules identifies nephron segment-specific transcriptomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2669–2677, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hato T, Winfree S, Day R, Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA, Yoder MC, et al.: Two-photon intravital fluorescence lifetime imaging of the kidney reveals cell-type specific metabolic signatures. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2420–2430, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maack T, Johnson V, Kau ST, Figueiredo J, Sigulem D: Renal filtration, transport, and metabolism of low-molecular-weight proteins: A review. Kidney Int 16: 251–270, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yokota S, Tsuji H, Kato K: Immunocytochemical localization of cathepsin H in rat kidney. Light and electron microscopic study. Histochemistry 85: 223–230, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen JT, Nielsen S, Christensen EI: Handling of lysozyme in isolated perfused proximal tubules. Am J Physiol 251: F822–F830, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schutte-Nutgen K, Edeling M, Mendl G, Krahn MP, Edemir B, Weide T, et al. : Getting a Notch closer to renal dysfunction: Activated Notch suppresses expression of the adaptor protein Disabled-2 in tubular epithelial cells [published online ahead of print July 27, 2018]. FASEB J 10.1096/fj.201800392RR [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Perez Bay AE, Schreiner R, Benedicto I, Paz Marzolo M, Banfelder J, Weinstein AM, et al.: The fast-recycling receptor Megalin defines the apical recycling pathway of epithelial cells. Nat Commun 7: 11550, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sumpio BE, Maack T: Kinetics, competition, and selectivity of tubular absorption of proteins. Am J Physiol 243: F379–F392, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christensen EI, Maunsbach AB: Effects of dextran on lysosomal ultrastructure and protein digestion in renal proximal tubule. Kidney Int 16: 301–311, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaide Chevronnay HP, Janssens V, Van Der Smissen P, N’Kuli F, Nevo N, Guiot Y, et al.: Time course of pathogenic and adaptation mechanisms in cystinotic mouse kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1256–1269, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mori KP, Yokoi H, Kasahara M, Imamaki H, Ishii A, Kuwabara T, et al.: Increase of total nephron albumin filtration and reabsorption in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 278–289, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sabbisetti VS, Ito K, Wang C, Yang L, Mefferd SC, Bonventre JV: Novel assays for detection of urinary KIM-1 in mouse models of kidney injury. Toxicol Sci 131: 13–25, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luciani A, Sirac C, Terryn S, Javaugue V, Prange JA, Bender S, et al.: Impaired lysosomal function underlies monoclonal light chain-associated renal fanconi syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2049–2061, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dickenmann M, Oettl T, Mihatsch MJ: Osmotic nephrosis: Acute kidney injury with accumulation of proximal tubular lysosomes due to administration of exogenous solutes. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 491–503, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klingberg A, Hasenberg A, Ludwig-Portugall I, Medyukhina A, Männ L, Brenzel A, et al.: Fully automated evaluation of total glomerular number and capillary tuft size in nephritic kidneys using lightsheet microscopy. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 452–459, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torres R, Velazquez H, Chang JJ, Levene MJ, Moeckel G, Desir GV, et al.: Three-dimensional morphology by multiphoton microscopy with clearing in a model of cisplatin-induced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1102–1112, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright FS, Giebisch G: Glomerular filtration in single nephrons. Kidney Int 1: 201–209, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhai XY, Thomsen JS, Birn H, Kristoffersen IB, Andreasen A, Christensen EI: Three-dimensional reconstruction of the mouse nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 77–88, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner MC, Myslinski J, Pratap S, Flores B, Rhodes G, Campos-Bilderback SB, et al.: Mechanism of increased clearance of glycated albumin by proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F1089–F1102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.